1. Introduction

As economic globalization deepens, and in conjunction with China's progressive exchange rate system reforms, the frequency and magnitude of international capital flows into and out of China have surged. This dynamic environment has forged a more intricate coordination between exchange rate shocks and asset price volatility. The interaction between these two factors has become a key concern for policymakers and economists alike. Post the global financial crisis of 2009, traditional monetary policy has faced increasing skepticism regarding its effectiveness in stabilizing both asset prices and inflation. This period has witnessed a shift towards the utilization of macroprudential policy, embraced as an essential tool to mitigate systemic financial risks and temper asset price fluctuations. Under these evolving circumstances, the exploration of a balanced and synergistic approach that combines macroprudential and monetary policies is not only theoretically intriguing but carries substantial practical implications. This study aims to probe in depth the ways in which these twin objectives of asset price and price level stability can be attained, particularly under the influence of exchange rate shocks. By unearthing the nuanced interplays between these economic forces, this research seeks to shed light on how a coordinated policy framework can be more effectively crafted, thereby contributing to the broader understanding of modern economic dynamics and policy implementation.

Asset Price Volatility Under Exchange Rate Shocks. Previous research on asset price volatility under exchange rate shocks has contributed valuable insights. Lin analyzes the relationship between exchange rate shocks and stock prices in emerging Asian markets and concludes that exchange rate shocks can cause significant volatility in asset prices(Lin, 2012). Zhu and Liu argue that appreciation of the RMB may lead to capital inflow, which can result in further appreciation of the RMB and increases in asset price(Zhu and Liu, 2010). Further appreciation of the RMB can exacerbate the increase in asset price. Yang and Zhang empirically analyze the relationship between real exchange rate shock, short-term international capital flow, and asset price volatility after China’s exchange rate reform and conclude that there is a significant correlation between exchange rate shock and asset price volatility(Yang and Zhang, 2014). Chen et al. obtain similar conclusions(Chen et al., 2020).

Diverging Views on Monetary Policy and Asset Price Volatility: While there is a consistent view on the relationship between exchange rate shock and asset price volatility, two distinct perspectives exist regarding whether monetary policy should focus on asset price, and relevant strategies have been proposed based on them to curb asset price volatility. Cecchetti argues that monetary policy giving consideration to movements in asset prices can help reduce the likelihood of asset price bubbles forming(Cecchetti et al., 2000). Borio and Lowe argue that a monetary policy targeting asset prices can help mitigate financial imbalances arising from swings in asset prices(Borio and Lowe, 2002). Barthélemy et al. also suggests that a two-pillar monetary policy strategy targeting both asset price and inflation is more reasonable than that only targeting inflation(Barthélemy et al., 2011). Lambertini et al. and Notarpietro and Siviero show that monetary policy that considers asset prices and credit can improve the implementation effectiveness of monetary policy(Lambertini et al., 2011; Notarpietro and Siviero, 2015). Similar conclusions have been obtained by scholars in China (Zhao and Gao, 2009; Li and Ma, 2010; Koivu, 2012; Chen et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2013). Domestic scholars Yang and Lang that the asset price of monetary policy can smooth out the fluctuations in the bubble and stabilize the economy(Gilchrist and Leahy, 2002; Yang and Lang, 2022). However, the quantitative easing (QE) of monetary policy used as a bailout by many central banks (such as the US Federal Reserve System, the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of England, and the Bank of Japan) after the global financial crisis in 2009 failed to show a significant effect, indicating that monetary policy is unable to stabilize asset price and price level at the same time. McDonald and Stokes argues that monetary policy should not respond to asset price fluctuations(McDonald and Stokes, 2011). Bernanke suggests further that the financial crisis in 2009 was rooted in the ineffective regulation of nontraditional mortgages(Bernanke, 2010). Kontonikas and Ioannidis also argue that monetary policy should not respond to asset price asset price movements, as such as policy could lead to more variability in output and inflation(Kontonikas and Ioannidis, 2005). Carlstrom et al. show that monetary policy is not effective in regulating asset price volatility(Carlstrom and Fuerst, 1997). De Fiore et al., Gomis-Porqueras and Sanche show that inflation-focused monetary policy is very close to an optimal one and asset price volatility should not be a focus of monetary policy as a result (Fiore et al., 2009; Gomis-Porqueras and Sanches, 2013). Semmler and Zhang (Semmler and Zhang, 2007) , Ma(Ma, 2013), Feng and Zheng and other scholars in China have obtained similar conclusions(Feng and Zheng, 2016). Domestic scholars Zhang et al. believe that when there is a large asset price bubble, the need to carefully use the “Headwind and move” monetary policy rules(Zhang et al., 2021).

Macroprudential Policy as a Response. After the global financial crisis in 2009, many scholars suggest that independent and targeted policy tools should be used to effectively regulate asset price movements. Nair and Anand argue that monetary policy is not the best policy to deal with asset price volatility or expansion in credit, and that macroprudential policy is more appropriate to achieve both price stability and financial stability(Nair and Anand, 2020). Ma argues that, without embedding variables other than output gap and inflation, effective coordination among monetary, credit, and macroprudential policies could achieve stability of both price level and asset price(Ma, 2013). Cheng and Meng suggest that the coordination of macroprudential and monetary policies targeting asset price and inflation, respectively, could achieve the stability of both asset price and price level in China(Cheng and Meng, 2017). According to Lu et al.(Lu et al., 2021), both the loan-to-value and Capital adequacy ratio macroprudential policy tools are matched by the extended Taylor rule as a monetary policy tool, it is the optimal tool collocation of financial regulation and supervision under the current situation of our country. According to Zhang in the “Two-pillar” policy framework, monetary policy has a good effect on inflation, at the same time, the macroprudential policy is also relatively effective in suppressing systemic risks, on the whole, the macro-stability of the regulatory effect is better(Zhang, 2022). Liu and Zhang argue that a “Dual pillar” regulatory framework of stable and reliable monetary policy and macroprudential policy is needed to achieve steady progress in economic development, it is an important issue in China's macro-economic policy regulation(Liu and Zhang, 2023).

Although there is a generally consistent view that monetary policy cannot simultaneously achieve stability of both asset price and price level in existing literature, not many studies have examined how to effectively curb asset price volatility based on price level stability, especially how to effectively damp asset price volatility under exchange rate shocks based on price level stability. In this paper, an open-economy DSGE model is constructed considering China’s specific situation and based on Bayesian estimation. Using numerical simulation, we try to analyze how to effectively coordinate macroprudential and monetary policies to curb asset price volatility under exchange rate shocks based on price stability. There are three problems needing to be solved: (1) how to set the objectives of co-acting polices, i.e., how to choose the appropriate target variables for each policy in the coordination mechanism to use it to good effect; (2) the performance of the coordination mechanism, i.e., whether the co-acting macroprudential and monetary policies can effectively curb asset price volatility on the basis of price level stability; and (3) which exchange rate regime, the managed one or the unregulated one, should be chosen for the coordination mechanism, i.e., which exchange rate regime is more helpful in China’s current specific situation. The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 proposes our model;

Section 3 is about parameter estimation;

Section 4 is about simulation analysis; and

Section 5 is the conclusion.

2. The Model

In this paper, based on the classical setting of Unsal (Unsal, 2011), the following open-economy DSGE model is constructed by taking into account the specific situation of China. The model includes two economies, the domestic one and the foreign one, with each containing actors in microeconomics such as representative households, different types of firms, entrepreneurs, and authorities making policies. Each actor seeks to achieve its goal, i.e., maximizing the expected benefits, under its own constraints. In addition, without affecting the conclusions of the study, the two economies, though different in the size, are assumed to share the same market structure for consumption and capital goods.

2.1. Representative Households

There is an infinity of homogeneous infinitely lived households in the domestic economy, who decide their consumption demand, labor supply and actual money balance/stock to maximize the sum of their discounted lifetime utility, i.e.:

where,

is the household consumption,

is the actual money balance held by the household,

is the labor supply,

is the household’s subjective discount factor,

is the weight of actual money balance in household utility, and

and

are the inverse of the elasticity of intertemporal substitution in household consumption and the inverse of labor supply, respectively. The representative household consumes a basket of goods with some produced by domestic firms and some produced by foreign firms. The representative household’s basket of consumption goods can be represented by the following Constant Elasticity of Substitution (CES) function:

where,

and

are domestic and foreign goods, respectively;

is the share of the domestically produced goods in the consumption basket, which can be used to measure the degree of openness of the domestic economy; and

γ is the elasticity of substitution between domestic and foreign goods. On the assumption of a symmetric equilibrium, the household’s optimal demand for domestic and foreign consumer goods can be obtained based on dynamic optimization theory:

where,

and

represent the prices of domestic and foreign consumer goods, respectively; and

denotes the price of the consumption basket. The aforesaid three variables satisfy the following conditions:

Let denote the real exchange rate, then , where is the nominal exchange rate, and is the price of imported consumption goods in foreign currency; let λ be the elasticity of substitution between foreign goods, then . As owners of firms, households participate in domestic and foreign financial markets: they lend their savings () in domestic currency, and borrow money () from international financial markets in foreign currency, with interest rates of and , respectively; where denotes the risk premium to be paid by households when they borrow from the foreign financial market, then .

Households earn income by providing labor and from savings, share profits of firms and receive transfers from the government to meet their demand for consumption and investment, with their budget constraints as follows:

where,

denotes wage rate,

denotes the profit from firms and

denotes the transfers from the government.

The representative households choose their optimal paths for

in order to maximize their discounted lifetime utility subject to the budget constraint and the available one-price condition as follows:

Get the conditional expectations of (8) and (9) to obtain the household intertemporal stochastic Euler equations as follows:

where,

and

denote the risk-free interest rates of domestic and foreign bonds, respectively; and

and

denote the domestic and foreign inflation rates, respectively.

2.2 Firms

2.2.1 Production Firms

A monopolistically competitive production firm provides goods using the following Cobb-Douglas (CD) production function with constant scale and returns:

where,

denotes the total factor productivity,

denotes the labor input, and

denotes the capital input. Firms can face quadratic menu costs in changing price of both domestic and foreign markets, which are expressed as

and

, respectively. This results in a gradual adjustment in the prices of goods in both markets. The combination of local currency pricing together with nominal price stickiness implies that fluctuations in the nominal exchange rate have a smaller impact on export prices so that exchange rate pass-through to export prices is relatively small in the short run

As firms are owned by households, the firm maximizes its future profits using the household’s intertemporal rate of substitution in consumption:

Assuming that goods of production firms have the same elasticities in both markets, the demand for good in two markets can be written as:

2.2.2. Importing Firms

In domestic market, there are monopolistically competitive importing firms who buy foreign goods and then sell them to the domestic market at prices . They are also subject to a price adjustment cost analogous to the production firms. This implies that the short run exchange rate pass-through to import prices is also relatively small.

2.2.3. Unfinished Capital Producing Firms

In domestic market, there is another set of monopolistically competitive firms, the unfinished capital producing firms, who use purchased

and rented

to produce unfinished capital goods, where

comprises domestic and foreign investments.

And the domestic and imported investments’ prices are assumed to be the same, then the nominal price of a unit of investment equals the domestic price level, . This implies and .

Let

be the discount rate of unfinished capital producing firm

, then the adjusted unit cost of

is, and the evolution equation of

can be expressed as follows:

According to Kiyotaki & Moore (1997), the production function of the unfinished capital producing firm can be expressed as:

Following the profit maximization principle, the nominal price of a unit of asset is:

2.3. Finished Capital Producing Firms

It is assumed that there is a continuum of entrepreneurs as finished capital producing firms

l ∈ [0,1]. Each entrepreneur has access to a stochastic technology in transforming

units of unfinished capital into

units of finished capital goods, where

, and satisfies the following two conditions: 1) it obeys a random distribution with mean of 1; 2) for the domain of definition, its distribution function

satisfies:

Entrepreneurs know changes

, but the lenders can only observe it at a monitoring cost which is assumed to be a certain fraction of the return

μ(1 >

μ > 0). According to the classic setting of Bernanke and Gertler (Bernanke and Gertler, 2012), the contract between the entrepreneur and the lender is a standard debt contract characterized by a default threshold

such that: 1) if

, the lender receives a fixed return in the form of a contracted interest on the debt; 2) If

, then the borrower defaults, the lender audits by paying the monitoring cost. Therefore, the expected returns to entrepreneurs and lenders, respectively, are as follows:

where,

denotes the return to capital,

is the entrepreneurs’ share of the total return, and

is the borrowers’ share of the total return. In domestic and foreign markets, the opportunity cost faced by the lenders when lending is the interest rates in two markets. To ensure the lenders will participate in lending, the following condition must be satisfied:

The optimal contract ensures the capital demand of entrepreneurs and a cut off value such that the entrepreneurs will achieve its goal of maximizing profits. The first order conditions yield:

where,

is the risk premium faced by the entrepreneurs in borrowing. As known from (23), entrepreneurs may take on more risky projects to obtain high-risk premium, which can raise the probability of default. In order to guarantee that self-financing never occurs and borrowing constraints on debt are always binding, we follow Kiyotaki and Moore (Kiyotaki and Moore, 1997), in assuming that shock

is independent of all other shocks and identical across entrepreneurs and that each entrepreneur faces the same contract specified by the cut off value and the external finance premium. Then the expected return on capital can be expressed as:

As known from (24), due to investment adjustment costs and depreciation, entrepreneurs’ return on capital, , is not identical to the rental rate of capital, Rt. In addition, is the sum of the rental rate on capital paid by the production firms, the rental rate on capital from the firms that produce unfinished capital goods, and the value of the capital stock, after the adjustment for the capital price inflation, Qt+1/Qt.

2.4. Macroprudential Policy

Whether in the form of countercyclical capital provision or loan-to-value ceiling, or some other type, macroprudential policy entails higher costs for financial intermediaries. We focus on a generic case where the implementation of macroprudential measures leads to additional cost to financial intermediaries. These costs are then reflected to borrowers in the form of higher interest rates on their loans. The increase in the lending rates, i.e., the “regulation premium” brought by macroprudential measures, is a function of nominal credit growth and can affect the spread between lending rate and deposit rate. According to Kannan et al.(Kannan et al., 2012), the cost of financing in the monopolistically competitive domestic and foreign financial markets can be written as:

where,

RPt is the regulation premium, which is defined a function of the nominal credit growth:

Based on above (25) for macroprudential policy, it is implicit that the policy objective is to regulate the aggregate credit activity in both domestic and foreign markets to dampen asset price volatility.

2.5. Monetary Policy

Considering the market-oriented interest rate reform being pushed ahead in China and based on the classical setting of Mei and Gong(Mei and Gong, 2011), we adopt the following open Taylor rule for monetary policy:

where,

is the smoothing coefficient of the nominal interest rate,

,

,

and

are the response coefficients of interest rate to real output, inflation rate, capital price and nominal exchange rate, respectively. Based on above (27), the authority for monetary policies makes the optimal response to the output, inflation rate, capital price, and exchange rate shocks by adjusting the nominal interest rate to achieve healthy economic development. Without affecting the findings of the study, we assume that domestic and foreign monetary policies have the same characteristics.

When goes to infinity, the interest rate responds infinitely to the deviation of the domestic commodity inflation from the equilibrium level, which indicates that the domestic monetary policy keeps the domestic price unchanged by targeting inflation and does not respond to the changes in imported foreign goods and exchange rate, in which case the exchange rate is not subject to any policy intervention, just like the situation under a floating exchange rate system; when goes to infinity, the domestic country’s monetary policy on the nominal exchange rate deviates from the equilibrium level infinitely, in which case the exchange rate is stable at a fixed value, just like the situation under a fixed exchange rate system; when is zero and the values of other coefficients are within their normal ranges, the monetary policy reacts to output, inflation, asset price and the nominal exchange rate, in which case, a larger indicates more stringent control of exchange rate fluctuations, just like the situation under a managed floating exchange rate regime.

2.6. Resource Constraints

At equilibrium, all optimality conditions are satisfied, all markets are cleared, and the resource constraints are as follows:

Where, LIM,t and LIK,t are the employment of import-oriented firms and unfinished capital producing firms, respectively.

2.7. Random Shock Process

Foreign credit shock: ln (

)=

Domestic credit shock: ln (

)=

Domestic interest rate shock: ln (

)

Nominal interest rate shock: ln (

)

Asset price increase rate shock: ln (

)

Random disturbance term in the above (31) - (36) obeys the distribution with mean = 0 and variance = , where .

3. Parameter Calibration and Estimation

3.1. Data Processing

To avoid possible random singularity problems in parameter estimation, six observed variables, including gross domestic product (GDP), total imports consumption, inflation rate, nominal interest rate, nominal exchange rate and social credit growth rate, are selected in this paper. As China has implemented a managed floating exchange rate system since July 21, 2005, the sample is chosen from the first quarter of 2006 to the fourth quarter of 2019. All data are obtained from the World Bank and CCER databases and processed using the HP filtering method to eliminate the adverse effects of outliers on parameter estimation based on eliminating seasonal fluctuations.

3.2. Parameter Calibration

For representative households, we set the discount factor to 0.9900 according to Zhang and Gong (Zhang and Gong, 2018); set the weight of real money balance in household utility and the inverse of labor supply elasticity to 0.3210 and 1.0300, respectively, according to Cheng and Meng(Cheng and Meng, 2017); set the inverse of the intertemporal elasticity of substitution of household consumption to 2.11 according to Deng and Xie (Deng and Xie, 2020); adjust the stickiness of unit capital adjustment cost to 5.0000 according to Zhuang et al. (Zhuang et al., 2012) ; adjust the quarterly depreciation rate of capital to 0.0250 according to Deng and Tang (Deng and Tang, 2012); and adjust the premium risk coefficient assumed when borrowing in foreign financial markets, the elasticity of substitution between foreign goods to 0.0600 and 6.000, respectively, and set the elasticity of substitution between domestic and foreign goods to 1.5 according to Unsal(Unsal, 2011).

For the production function, the elasticity of capital output is adjusted to 0.4500 based on data on labor compensation, fixed capital depreciation, and operating surplus for 2005-2019 (from the China Statistical Yearbooks); and the elasticity of substitution for intermediate goods is adjusted to 5.9800 based on the statistics on the cost-plus rate of firms at steady state (20%). In the steady state, the share of domestic consumption goods in total consumption goods is set to 0.9600 based on share of China’s consumption imports in the UN BEC classification (5%-7%); the steady-state risk-free interest rate is adjusted to 1.0086 based on the China’s benchmark deposit rate data for the period 2005-2019 (from the Financial Statistics Database of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences); the steady-state inflation rate is set to 1.0290 according to the inflation statistics for the period 2005-2019 (from the CEInet database); and the steady-state C/Y and I/Y are adjusted to 0.4800 and 0.4320, respectively, based on the annual expenditure-method GDP data for the period 2005-2019 (from the CEInet database).

3.3. Parameter Estimation

The Bayesian estimation method is used as follows to estimate the parameters of the dynamic characteristics of the response model. Following Unsal(Unsal, 2011), the prior information and the set prior distribution of relevant parameters are given in the second to fourth columns, and the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the prior distribution of the parameters are set according to the actual situation of China. Using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method, samples are drawn 10,000 times for each parameter, and the posterior median is taken as the estimated value of the parameter. The estimation process is completed using the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm. The specific estimation results are shown in

Table 1.

4. Simulation Analysis

To make the constructed DSGE model applicable to the actual problems in Chinese economy, the impulse response analysis of the short-run impact of exogenous stochastic shocks on asset prices and the variance decomposition analysis of the long-run impact are done respectively. In addition, the change in social welfare with coordinated or non-coordinated policies is analyzed making use of the dominant characteristics of the household utility function in the DSGE model. Finally, robustness test is done to ensure the practical value of our findings.

4.1. Impulse Response Analysis

4.1.1. Impulse Responses of Asset Prices to Random Shocks Under Independent Policy Mix

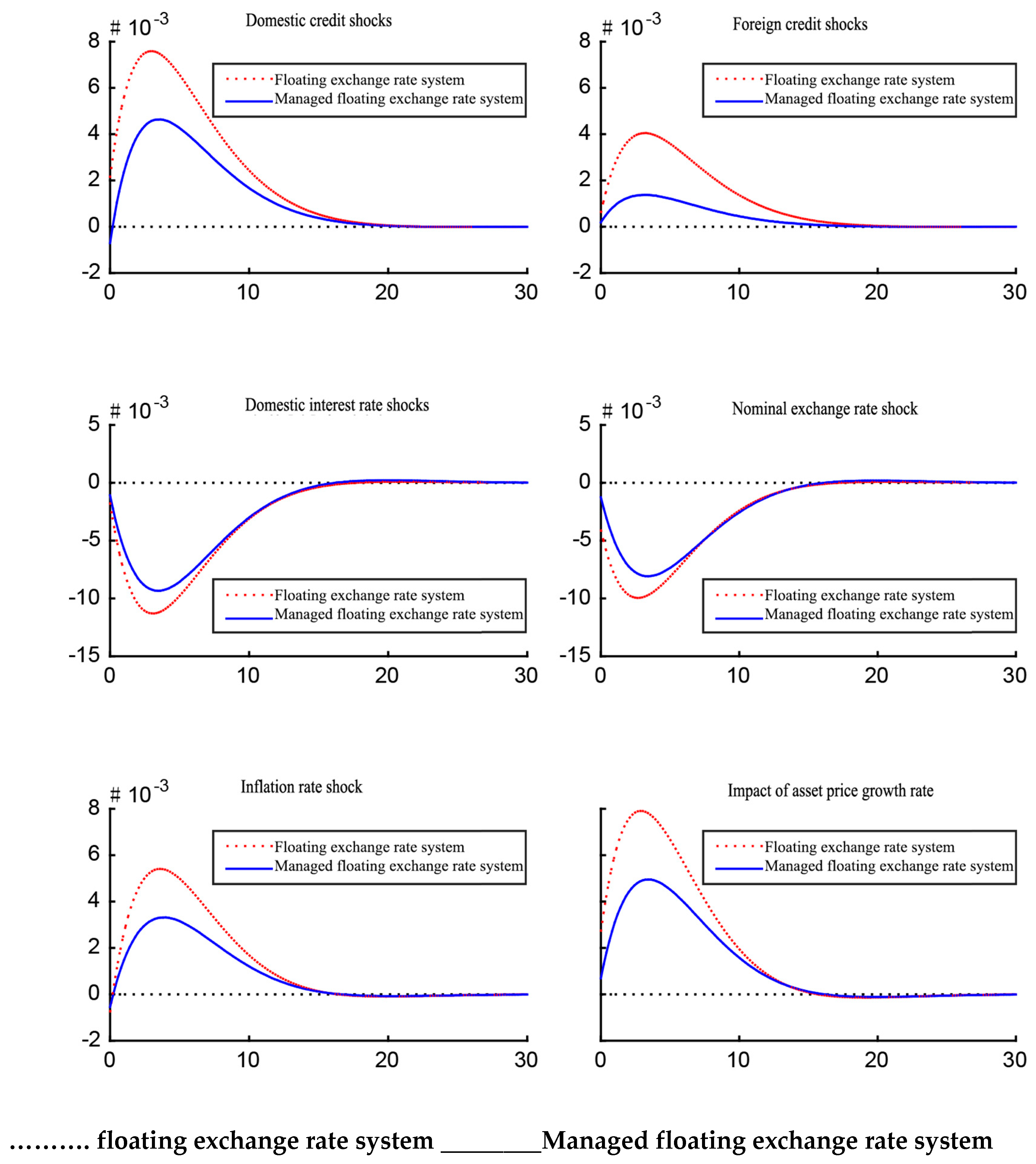

As seen from

Figure 1, (1) the main factors affecting China’s asset prices under independent policy mix in an open economy environment are domestic interest rate, nominal exchange rate, domestic credit and asset price growth shocks, and the impacts of inflation rate and foreign credit shocks are weaker, indicating that China’s asset prices are increasingly influenced by external economic factors with China’s deepening of opening up to the outside world; and (2) under the independent policy mix, the managed floating exchange rate system performs better than the floating exchange rate system, mainly because the capital market is not fully open under the managed floating exchange rate system, which weakens the influence of external economic factors on China’s asset prices and thus makes China’s asset prices less volatile.

4.1.2. Impulse responses of Asset Prices to Random Shocks Under Coordinated Policy Mix

As seen from

Figure 2, (1) the main factors affecting China’s asset prices under the coordinated policy mix in an open economy environment are consistent with the findings under the independent policy mix, which further indicates that China’s asset prices are increasingly influenced by external economic factors as China’s opening up to the outside world deepens; (2) under the coordinated policy mix, the managed floating exchange rate system also performs better than the floating exchange rate system, which further indicates that the capital market not fully open under the managed floating exchange rate system can weaken the influence of external economic factors on China’s asset prices; and (3) the coordinated policy mix has a more significant effect than the independent policy mix, mainly because the strategies of implementing both macroprudential policy targeting asset prices and monetary policy targeting price levels, respectively, under exchange rate shocks in an open environment can avoid problems such as policy overlapping and policy conflict that may occur when the two policies are implemented independently in the case of independent policy mix.

4.2. Variance Decomposition Analysis

As our impulse response analysis has shown that a managed floating exchange rate regime performs better than a floating exchange rate regime, only the variance decomposition results of important economic variables under a managed floating exchange rate regime with infinite horizons are given here in

Table 2 below (%).

As we can see from the variance decomposition, (1) in a managed floating exchange rate regime, under both independent and coordinated policy mix, domestic interest rate, nominal exchange rate, domestic credit and asset price growth shocks can explain more than 77% of asset price volatility (77.84% vs. 80.08%); and (2) the coordinated policy mix can explain asset price volatility more compared with the independent policy mix. Therefore, domestic interest rate, nominal exchange rate and domestic credit are the important factors influencing the asset price volatility in China, and the reasonable coordination of macroprudential and monetary policies can effectively curb asset price volatility under exchange rate shocks.

4.3. Welfare Analysis

Following Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe, 2007), the social welfare level,

Wel, in period

t, can be described as:

According to the compensatory consumption change proposed by Lucas (Lucas, 2001), policy change can lead to a reallocation of consumption resources. Let

denote compensatory consumption cost, then the compensatory consumption is:

where,

and

are the social welfare levels at equilibrium in the independent and coordinated policy mixes, respectively; and

and

are the social welfare levels in period

t in the independent and coordinated policy mixes, respectively.

It can be solved to get

. Then, the social welfare loss function is as follows:

The social welfare loss is calculated under four conditions using (39), and the results are shown in

Table 3.

As we can see from

Table 3, compared with the independent policy mix, the coordinated policy mix can significantly improve the welfare level of the society while damping asset price volatility. This suggests that, to effectively curb asset price volatility in response to exchange rate shocks, one cannot count on a simple combination of two policies but should achieve effective coordination. Effective coordination of two policies can further improve the welfare level of society while effectively curbing asset price volatility under exchange rate shocks.

4.4. Robustness Analysis

Given that much of the domestic literature suggests that the instability of monetary policy in China is mainly reflected in the inadequate response of interest rates to the inflation gap, the robustness of the model is analyzed in terms of forward-looking monetary policy rules to verify the reliability of the conclusions obtained.

We test the robustness of the model based on a forward-looking monetary policy rule in the following form:

where,

denotes the expected inflation rate. According to rational expectations theory, the actual inflation rate value in period

t+1 can be used as the expected inflation rate value in period

t. This rule implies that: if the inflation expectation is higher than the inflation target, then the interest rate should be increased; and vice versa.

Table 4 provides the results of the Bayesian estimation based on the forward-looking monetary policy rule.

As can be seen from the table, (1) the response coefficient of the inflation gap is estimated as 1.4835, which indicates that, although the forward-looking monetary policy rule contains more information on inflation expectations, it is only slightly higher than the estimate based on the contemporaneous monetary policy rule; and (2) the estimates for the other parameters of the model are all within a reasonable range and are generally consistent with the estimation results in

Table 1. Thus, the DSGE model constructed in this paper is relatively robust.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, an open-economy DSGE model specific to China’s situation is constructed to explore the synergistic mechanism of macroprudential and monetary policies in the context of asset price fluctuations under exchange rate shocks, employing numerical simulation methods grounded in Bayesian estimation. This research contributes to the existing body of knowledge by offering innovative insights into the complex interplay of these policies. The following results are obtained.

(1) Target Setting for coordination: In contrast to traditional approaches that have generally considered these policies in isolation(Borio and Zhu, 2012), this research demonstrates that a well-defined and targeted coordination between macroprudential and monetary policies focusing on asset price and price level stability, respectively, can robustly stabilize both under exchange rate shocks. This represents an important advancement in understanding the mutual reinforcement of these policies.

(2) Performance of the coordination and Welfare Impact: Extending beyond existing studies that have mainly focused on stabilization(Gambacorta and Signoretti, 2014), this paper finds that reasonable coordination of macroprudential and monetary policies serves to not only dampen asset price fluctuations but also enhance social welfare. Additionally, the finding that countercyclical macroprudential policy can suppress capital price volatility and improve welfare represents a novel contribution, advancing our understanding of how cyclical adjustments can be leveraged for broader societal benefits.

(3) For the choice of exchange rate system of coordination: Building upon the existing literature on exchange rate management(Aizenman et al., 2016), this research uniquely explores the comparative advantages of managed floating versus floating exchange rate systems. It demonstrates that a managed floating system can circumvent potential “policy overlapping” and “policy conflict,” issues that may arise with a floating system. This insight represents a significant breakthrough, providing actionable guidance for policy design in complex open economies like China.

In summary, this paper contributes a pioneering exploration of the interwoven dynamics between macroprudential and monetary policies, and exchange rate systems, offering new empirical and theoretical insights that extend beyond the existing literature. These findings provide not only a theoretical framework but also practical policy implications for economists and policymakers in China and potentially other emerging economies, striving to balance stability and welfare in a turbulent global economic landscape.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Juan Gao and Fangnan Cheng; Data curation, Juan Gao; Formal analysis, Ling Cheng; Funding acquisition, Juan Gao and Fangnan Cheng; Investigation, Fangnan Cheng and Ling Cheng; Methodology, Juan Gao and Fangnan Cheng; Project administration, Fangnan Cheng and Liuhua Fang; Software, Fangnan Cheng and Liuhua Fang; Supervision, Fangnan Cheng; Writing – original draft, Juan Gao and Liuhua Fang; Writing – review & editing, Fangnan Cheng and Ling Cheng.

Funding

This research was funded by the Chongqing Municipal Education Commission Humanities and Social Sciences Research Base Project (grant no.20JD068); Chongqing Municipal Education Commission Humanities and Social Sciences Research Base Project (grant no. 22SKJD111); Guizhou Provincial Philosophical and Social Sciences Planning Project(23GZYB38).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aizenman, J.; Chinn, M.D.; Ito, H. Monetary policy spillovers and the trilemma in the new normal: Periphery country sensitivity to core country conditions. J. Int. Money Finance 2016, 68, 298–330, . [CrossRef]

- Barthélemy, J.; Clerc, L.; Marx, M. A two-pillar DSGE monetary policy model for the euro area. Econ. Model. 2011, 28, 1303–1316, . [CrossRef]

- Bernanke B, Gertler M (2012). New Perspectives on Asset Price Bubbles. Evanoff, D.D., Kaufman, G.G. and Malliaris, A.G. (eds): Oxford University Press, 173–210.

- Bernanke B S (2010). Monetary policy and the housing bubble. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- Borio C, Zhu H (2012). Capital regulation, risk-taking and monetary policy: A missing link in the transmission mechanism? Journal of Financial Stability, 8(4): 236-251.

- Borio C E V, Lowe P W (2002). Asset Prices, Financial and Monetary Stability: Exploring the Nexus. SSRN Electronic Journal, 114: 1-47.

- Carlstrom C T, Fuerst T S (1997). Agency Costs, Net Worth, and Business Fluctuations: A Computable General Equilibrium Analysis. The American Economic Review, 87(5): 893-910.

- Cecchetti S, Genberg H, Lipsky J (2000). Asset Prices and Central Bank Policy. ICMB and the CEPR, 2(2): 1-152.

- Chen J, Yuan W, Xiao W (2013). Liquidity, Implicit Information of Asset Prices and Monetary Policy Choice: Evidence from Housing Market and Stock Market in China. Economic Research Journal, 48(11): 43-55.

- Chen, L.; Du, Z.; Hu, Z. Impact of economic policy uncertainty on exchange rate volatility of China. Finance Res. Lett. 2019, 32, 101266, . [CrossRef]

- Cheng F, Meng W (2017). Coordination of Macro-prudential Policy and Monetary Policy: Based on a DSGE Model Based on Bayesian Estimation. Chinese Management Science, 25(1): 11-20.

- Deng G, Xie D (2020). Payment Delay, Exchange Rate Pass-through and Economic Fluctuations. Economic Research Journal, 55(2): 68-83.

- Deng Z, Tang W (2012). Effect of Government’s Pubic Expenditure on Stabilizing Economy. Economic Perspectives, (7): 19-24.

- Feng G, Zheng G (2016). Macroeconomic Effects of Asymmetric Monetary Policy Intervention on Asset Price Fluctuations in China —Simulation and Analysis Based on a Piecewise Linear NK-DSGE Model. China Industrial Economics, 10: 5-22.

- De Fiore, F.; Teles, P.; Tristani, O. Monetary Policy and the Financing of Firms. Am. Econ. Journal: Macroecon. 2011, 3, 112–142, . [CrossRef]

- Gambacorta L, Signoretti F M (2014). Should monetary policy lean against the wind?: An analysis based on a DSGE model with banking. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 43: 146-174.

- Gilchrist, S.; Leahy, J.V. Monetary policy and asset prices. J. Monetary Econ. 2002, 49, 75–97, . [CrossRef]

- Gomis-Porqueras, P.; Sanches, D. Optimal Monetary Policy in a Model of Money and Credit. J. Money, Crédit. Bank. 2013, 45, 701–730, . [CrossRef]

- Kannan, P.; Rabanal, P.; Scott, A.M. Monetary and Macroprudential Policy Rules in a Model with House Price Booms. B.E. J. Macroecon. 2012, 12, . [CrossRef]

- Kiyotaki N, Moore J (1997). Credit Cycles. Journal of Political Economy, 105(2): 211-248.

- Koivu, T. Monetary policy, asset prices and consumption in China. Econ. Syst. 2012, 36, 307–325, . [CrossRef]

- Kontonikas A, Ioannidis C (2005). Should monetary policy respond to asset price misalignments? Economic Modelling, 22(6): 1105-1121.

- Lambertini, L.; Mendicino, C.; Punzi, M.T. Leaning against boom–bust cycles in credit and housing prices. J. Econ. Dyn. Control. 2013, 37, 1500–1522, . [CrossRef]

- Li C, Ma W (2010). Should Monetary Policy Pay Close Attention to Asset Price and Exchange Rate? Journal of Finance and Economics, 25(2): 34-46.

- Lin, C.-H. The comovement between exchange rates and stock prices in the Asian emerging markets. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2011, 22, 161–172, . [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Zhang P (2023). Implicit Government Guarantee, Misallocation of Credit Resources and the "Dual-pillar" Framework Analysis Based on BGG-DSGE Model. Wuhan University Journal: Philosophy & Social Science, 76(1): 139-151.

- Lu J, Shen L, Huang Z (2021). Research on the Optimal Tool Choice of the Collocation of Macro-prudential Policy and Monetary Policy. Journal of Finance and Economics, (5): 4-15.

- Lucas R E (2001). Monetary Theory as a Basis for Monetary Policy. Leijonhufvud, A. (ed). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 96-142.

- Ma Y (2013). A DSGE model with Embedded Financial Factors and Macro Prudential Monetary Policy Rules. The Journal of World Economy, 36(7): 68-92.

- Mcdonald J F, Stokes H H (2011). Monetary Policy and the Housing Bubble. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 46(3): 437-451.

- Mei D, Gong L (2011). The Determinants of Exchange Rate Regime in the Emerging Economies. Economic Research Journal, 46(11): 73-88.

- Nair A R, Anand B (2020). Monetary policy and financial stability: Should central bank lean against the wind? Central Bank Review, 20(3): 133-142.

- Notarpietro, A.; Siviero, S. Optimal Monetary Policy Rules and House Prices: The Role of Financial Frictions. J. Money, Crédit. Bank. 2015, 47, 383–410, . [CrossRef]

- Schmitt-Grohé, S.; Uribe, M. Optimal simple and implementable monetary and fiscal rules. J. Monetary Econ. 2007, 54, 1702–1725, . [CrossRef]

- Semmler, W.; Zhang, W. Asset price volatility and monetary policy rules: A dynamic model and empirical evidence. Econ. Model. 2007, 24, 411–430, . [CrossRef]

- Unsal D (2011). Capital Flows and Financial Stability: Monetary Policy and Macropruden tial Responses. IMF Working Papers, 11(189): 1-27.

- Xiao W, Chen J, Yuan W (2013). Liquidity,Implicit Information of Asset Prices and Monetary Policy Choice:Evidence from Housing Market and Stock Market in China. Economic Research Journal, 48(11): 43-55.

- Yang D, Zhang Y (2014). RMB Real Exchange Rate, Short-term International Capital Inflow and Asset Price: An Analysis Based on TVP-VAR model. Journal of International Trade, (07): 155-165.

- Yang Q, Lang Y (2022). Reflection on Asset Prices in Inflation Target of Monetary Policy:From the Perspective of Asset Bubbles. Contemporary Finance & Economics, 2: 54-65.

- Zhang B (2022). The effects of Twin-Pillar Regulatory Frameworks: Based on Financial Stability and Macroscopic Stability. Nankai University, (2): 1-161.

- Zhang K, Gong L (2018). A Study of Fiscal Expenditure Multipliers in an Open Economy - An Analysis Based on a DSGE Model Incorporating Input-Output Structure. Management World, 34(06): 24-40+187.

- Zhang R, Guo X, Shen C (2021). “Financial Accelerator Effect” or “Rational Asset Price Bubble Effect”-Research on Time-varying Relationship based on Monetary Policy, Asset Prices and Economic Fluctuation. Journal of Guizhou University of Finance and Economics, 215(6): 36-47.

- Zhao J, Gao H (2009). Impact of Asset Price Fluctuation on China’s Monetary Policy: An Empirical Analysis Based on Quarterly Data, 1994-2006. Social Sciences in China, (2): 98-114+206.

- Zhu M, Liu L (2010). Short-run International Capital Flows, Exchange Rate and Asset Prices—An Empirical Study Based on Data After Exchange Rate Reform Since 2005. Finance & Trade Economics, (05): 5-13+135.

- Zhuang Z, Cui X, Gong L, Zhou H (2012). Expectations and Business Cycle: Can News Shocks Be a Major Source of China's Economic Fluctuations?. Economic Research Journal, 47(06): 46-59.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).