Submitted:

30 May 2024

Posted:

31 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Liquefaction

2.2. Determination of Hydroxyl Value

2.3. Foam Preparation

2.4. Foam Testing

2.5. FTIR Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

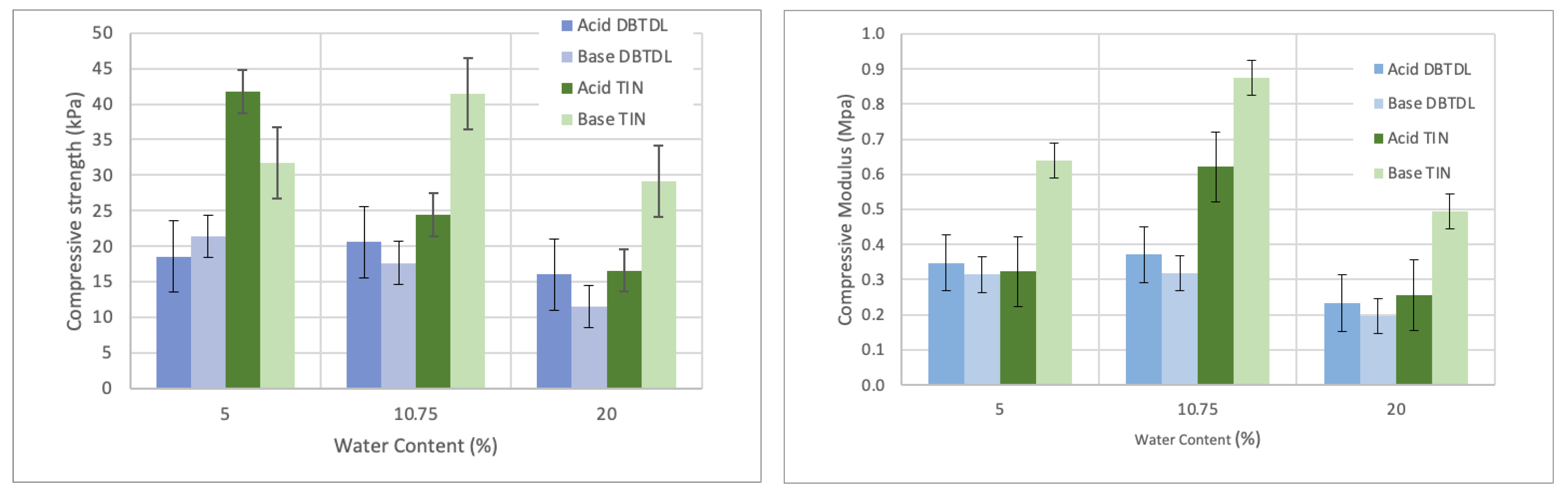

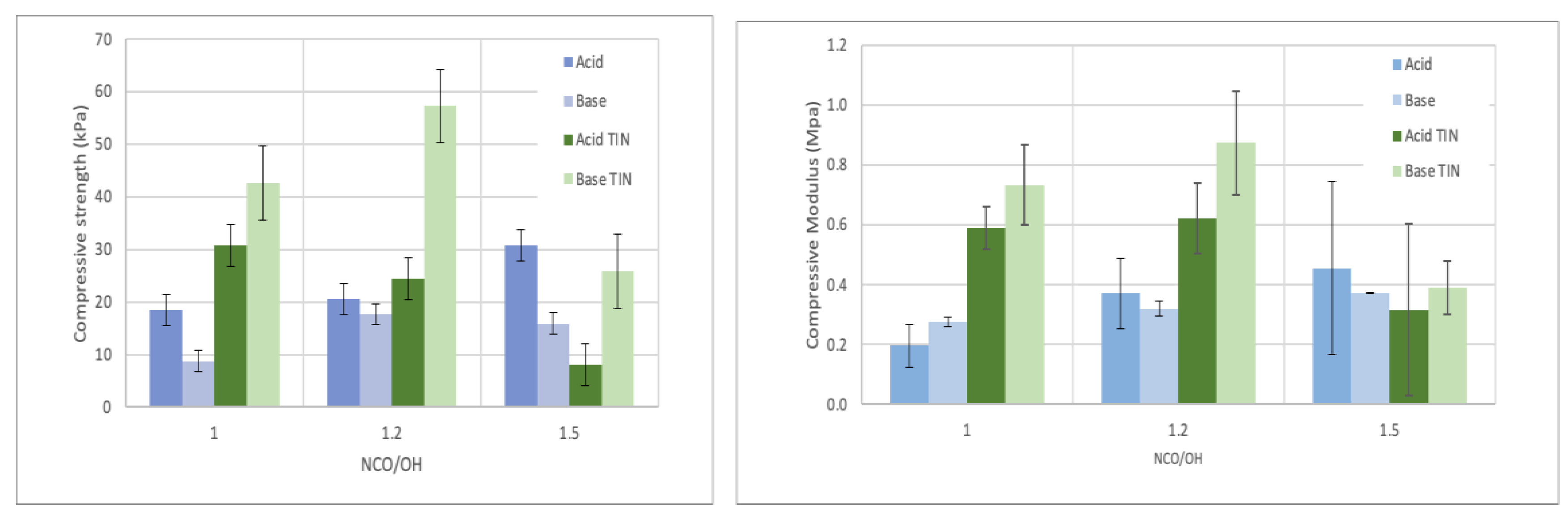

3.1. Mechanical Properties

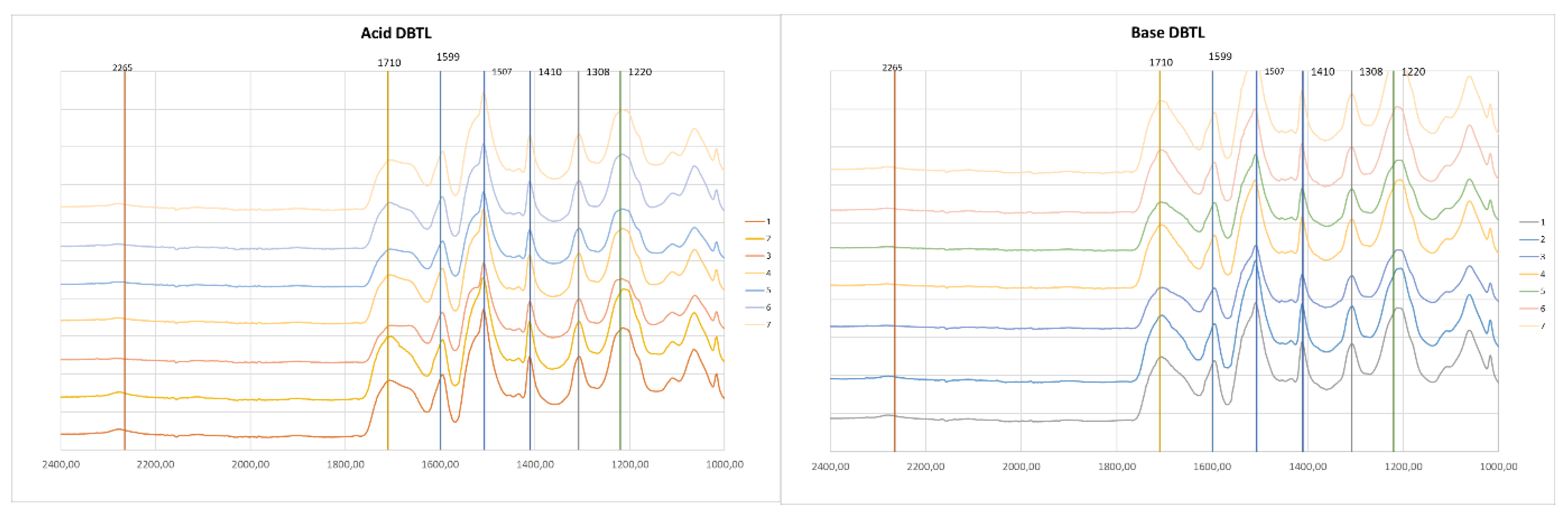

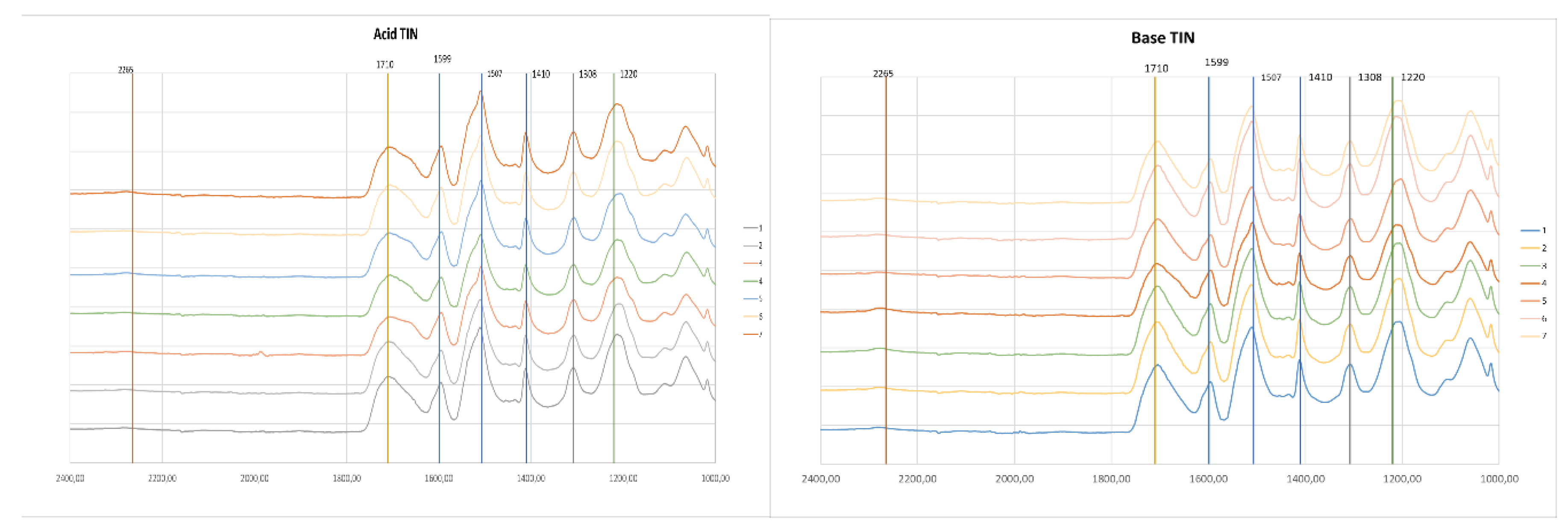

3.2. FTIR Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eling, B.; Tomović, Ž.; Schädler, V. Current and Future Trends in Polyurethanes: An Industrial Perspective. Macro Chemistry & Physics 2020, 221, 2000114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertaş, M.; Fidan, M.S.; Alma, M.H. Preparation and Characterization of Biodegradable Rigid Polyurethane Foams from the Liquefied Eucalyptus and Pine Woods. Wood Res.-Slovakia 2014, 59, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.; Zheng, Z.; Hse, C.Y. Microwave-Assisted Liquefaction of Wood with Polyhydric Alcohols and Its Application in Preparation of Polyurethane (PU) Foams. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products 2012, 70, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Jiang, J.; Hse, C.-Y.; Shupe, T.F. Preparation of Polyurethane Foams Using Fractionated Products in Liquefied Wood. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2014, 131, n/a-n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Pan, H.; Huang, Y.; Chung, Yh.; Zhang, X.; Feng, H. Rapid Liquefaction of Wood in Polyhydric Alcohols under Microwave Heating and Its Liquefied Products for Preparation of Rigid Polyurethane Foam. Open Materials Science Journal 2011, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, I.; Fernandes, A.P.; Ferreira, J.; Cruz-Lopes, L.; Esteves, B.M. Polyurethane Foams from Liquefied Eucalyptus Globulus Branches. BioResources 2019, 14, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hori, N.; Takemura, A. Optimization of Agricultural Wastes Liquefaction Process and Preparing Bio-Based Polyurethane Foams by the Obtained Polyols. Industrial Crops and Products 2019, 138, 111455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Luo, X.; Li, Y. Polyols and Polyurethanes from the Liquefaction of Lignocellulosic Biomass. ChemSusChem 2014, 7, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evtiouguina, M.; Barros-Timmons, A.; Cruz-Pinto, J.J.; Neto, C.P.; Belgacem, M.N.; Gandini, A. Oxypropylation of Cork and the Use of the Ensuing Polyols in Polyurethane Formulations. Biomacromolecules 2002, 3, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evtiouguina, M.; Margarida Barros, A.; Cruz-Pinto, J.J.; Pascoal Neto, C.; Belgacem, N.; Pavier, C.; Gandini, A. The Oxypropylation of Cork Residues: Preliminary Results. Bioresource Technology 2000, 73, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, B.; Cruz-Lopes, L.; Ferreira, J.; Domingos, I.; Nunes, L.; Pereira, H. Optimizing Douglas-Fir Bark Liquefaction in Mixtures of Glycerol and Polyethylene Glycol and KOH. Holzforschung 2018, 72, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Li, Y. Polyols and Polyurethane Foams from Base-Catalyzed Liquefaction of Lignocellulosic Biomass by Crude Glycerol: Effects of Crude Glycerol Impurities. Industrial Crops and Products 2014, 57, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiukaitytė-Grojzdek, E.; Kunaver, M.; Crestini, C. Lignin Structural Changes During Liquefaction in Acidified Ethylene Glycol. Journal of Wood Chemistry and Technology 2012, 32, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Ruan, X.; Cheng, X.; Lü, Q. Liquefaction of Lignin by Polyethyleneglycol and Glycerol. Bioresource Technology 2011, 102, 3581–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, B.; Gama, N.; Freire, C.; Barros-Timmons, A.; Brandão, I.; Silva, R.; Pascoal Neto, C.; Ferreira, A. Ecopolyol Production from Industrial Cork Powder via Acid Liquefaction Using Polyhydric Alcohols. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2014, 2, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ding, F.; Luo, C.; Xiong, L.; Chen, X. Liquefaction and Characterization of Acid Hydrolysis Residue of Corncob in Polyhydric Alcohols. Industrial Crops and Products 2012, 39, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, M.M.; Guerreiro, D.; Ferreira, O.; Bordado, J.C.; Santos, R.G. dos Heuristic Analysis of Eucalyptus Globulus Bark Depolymerization via Acid-Liquefaction. Cellulose 2017, 24, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldas, D.; Shiraishi, N. Liquefaction of Wood in the Presence of Polyol Using NaOH as a Catalyst and Its Application to Polyurethane Foams. International Journal of Polymeric Materials 1996, 33, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yona, A.M.C.; Budija, F.; Kričej, B.; Kutnar, A.; Pavlič, M.; Pori, P.; Tavzes, Č.; Petrič, M. Production of Biomaterials from Cork: Liquefaction in Polyhydric Alcohols at Moderate Temperatures. Industrial Crops and Products 2014, 54, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamiński, M.; Szymański, R.; Parzuchowski, P.; Antczak, A.; Szymona, K. Hyperbranched Polyglycerols with Bisphenol A Core as Glycerol-Derived Components of Polyurethane Wood Adhesives. BioResources 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Ding, X.; Du, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhao, M.; Dan, Y.; Jiang, L.; Chen, Y. Low-Temperature Performance Controlled by Hydroxyl Value in Polyethylene Glycol Enveloping Pt-Based Catalyst for CO/C3H6/NO Oxidation. Molecular Catalysis 2020, 484, 110740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Wan, Y.; Lei, H.; Yu, F.; Chen, P.; Lin, X.; Liu, Y.; Ruan, R. Liquefaction of Corn Stover Using Industrial Biodiesel Glycerol. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering 2009, 2, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, T.; Ono, H. Characterization of the Products Resulting from Ethylene Glycol Liquefaction of Cellulose. Journal of Wood Science 2001, 47, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Aratani, M.; Kubo, S.; Ono, H. Chemical Analysis of the Product in Acid-Catalyzed Solvolysis of Cellulose Using Polyethylene Glycol and Ethylene Carbonate. J Wood Sci 2007, 53, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, J.; Yan, N. Producing Bark-Based Polyols through Liquefaction: Effect of Liquefaction Temperature. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2013, 1, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.L.; Bordado, J.C. Recent Developments in Polyurethane Catalysis: Catalytic Mechanisms Review. Catalysis Reviews 2004, 46, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurańska, M.; Prociak, A.; Michalowski, S.; Zawadzińska, A. The Influence of Blowing Agents Type on Foaming Process and Properties of Rigid Polyurethane Foams. Polimery 2018, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.D.; Macosko, C.W.; Davis, H.T.; Nikolov, A.D.; Wasan, D.T. Role of Silicone Surfactant in Flexible Polyurethane Foam. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 1999, 215, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, B.K. Effects of Silicon Surfactant in Rigid Polyurethane Foams. Express Polymer Letters 2008, 2, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.S.; Choi, S.J.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, W.N.; Lee, H.S.; Sung, J.Y. Effects of Silicone Surfactant on the Cell Size and Thermal Conductivity of Rigid Polyurethane Foams by Environmentally Friendly Blowing Agents. Macromol. Res. 2009, 17, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chajęcka, J.M. Synthesis of Biodegradable and Biocompostable Polyesters. PhD Thesis, Dissertation, Instituo Superior Tecnico, Universide Tecnica de Lisboa, Lisboa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Domingos, I.; Ferreira, J.; Cruz-Lopes, L.; Esteves, B. Polyurethane Foams from Liquefied Orange Peel Wastes. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2019, 115, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cao, H.; Zhang, Y. Structures and Physical Properties of Rigid Polyurethane Foams with Water as the Sole Blowing Agent. Science in China Series B: Chemistry 2006, 49, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, A.A.; Nassar, M.; Emam, A.; Sultan, M. Preparation and Characterization of Rigid Polyurethane Foam Prepared from Sugar-Cane Bagasse Polyol. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2011, 129, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Yoshioka, M.; Shiraishi, N. Combined Liquefaction of Wood and Starch in a Polyethylene Glycol/Glycerin Blended Solvent. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 1993, 39, 930–938. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-H.; Teramoto, Y.; Shiraishi, N. Biodegradable Polyurethane Foam from Liquefied Waste Paper and Its Thermal Stability, Biodegradability, and Genotoxicity. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2002, 83, 1482–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Pang, H.; Yang, X.; Zhang, R.; Liao, B. Preparation and Characterization of Water-blown Polyurethane Foams from Liquefied Cornstalk Polyol. Journal of applied polymer science 2008, 110, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, N.; Yuan, Z.; Schmidt, J.; Xu, C. (Charles) Depolymerization of Lignins and Their Applications for the Preparation of Polyols and Rigid Polyurethane Foams: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 60, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.-J.; Yang, S.-R.; Kim, D.-H.; Park, J.-S. Characterization of Polyurethane Foam Prepared by Using Starch as Polyol. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2007, 103, 1544–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, H.; Tokunaga, Y.; Masuda, T.; Kiso, H.; Yoshimura, H. Characterization of Local Structures in Flexible Polyurethane Foams by Solid-State NMR and FTIR Spectroscopy. Journal of Cellular Plastics 2006, 42, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, M.M.; Skrovanek, D.J.; Hu, J.; Painter, P.C. Hydrogen Bonding in Polymer Blends. 1. FTIR Studies of Urethane-Ether Blends. Macromolecules 1988, 21, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardeş, M.; Yatmaz, H.C.; Öztürk, K. ZnO Nanorods Grown on Flexible Polyurethane Foam Surfaces for Photocatalytic Azo Dye Treatment. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 6605–6613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo; Wang; Ying Hydrogen-Bonding Properties of Segmented Polyether Poly (Urethane Urea) Copolymer. Macromolecules 1997, 30, 4405–4409. [CrossRef]

- Węgrzyk, G.; Grzęda, D.; Ryszkowska, J. The Effect of Mixing Pressure in a High-Pressure Machine on Morphological and Physical Properties of Free-Rising Rigid Polyurethane Foams—A Case Study. Materials 2023, 16, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, Y.; Kumagai, S.; Motokucho, S.; Kameda, T.; Saito, Y.; Watanabe, A.; Nakatani, H.; Yoshioka, T. Temperature-Dependent Pyrolysis Behavior of Polyurethane Elastomers with Different Hard- and Soft-Segment Compositions. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2020, 145, 104754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffanjon, P.; Grisgby, R.A.; Rister, E.L.; Zimmerman, R.L. Use of Real-Time FTIR to Characterize Kinetics of Amine Catalysts and to Develop New Grades for Various Polyurethane Applications, Including Low Emission Catalysts. Journal of Cellular Plastics 2003, 39, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reignier, J.; Méchin, F.; Sarbu, A. Chemical Gradients in PIR Foams as Probed by ATR-FTIR Analysis and Consequences on Fire Resistance. Polymer Testing 2021, 93, 106972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 48. Yi, S.; Cho, S.; Lee, C.-K.; Cho, Y.-J. Thermal Resistance of Polyurethane Adhesives Containing Aluminum Hydroxide and Dealkaline or Alkaline Lignin. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2024, 141, e55120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Peak assignment |

| 3400 | O-H stretching |

| 3290 | N-H stretching vibration of urethane groups |

| 2265 | Antisymmetric stretching vibration of NCO |

| 1730 | C=O stretching (free urethane) |

| 1710 | C=O stretching (hydrogen-bonded urethane) |

| 1670 | C=O stretching (urea) |

| 1593 | C-C stretching of the aromatic ring |

| 1530 | C-N stretching of urethane group |

| 1507 | N-H bending vibration |

| 1410 | C-N stretching of the aromatic ring |

| 1308 | Aliphatic C-H bending vibrations |

| 1200-1230 | C-N stretching of urethane group |

| 1096 | C-O-C stretching |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).