Introduction

Bowel is the extragenital site most frequently affected by endometriosis [

1]. Bowel endometriosis (BE) is defined as the presence of endometrial-like glands not only in the serosa and the sub-serosal tissue but also in the muscular layer of the bowel wall [

2,

3]. BE lesions are found in 8-12% of women with endometriosis and, of these, 90% are localized at the level of the sigma-rectum [

2]. Typical symptoms of BE are abdominal bloating, diarrhea, and constipation but it can also be asymptomatic [

4].

Treatment for BE is still a matter of debate: when endometriotic lesions cause bowel obstruction or severe sub-occlusion, surgery is necessary [

5]; in other cases, both surgical and medical treatments can be suitable options. Some authors support excisional surgery asserting that medical treatments provide limited benefit exerting an effect on the endometrial and smooth muscle component of the nodule, but not on the fibrotic one [

6,

7,

8]. However, several substantial improvements in bowel symptoms have been observed during treatment with oral estrogen-progestin contraceptive pills (OCs) or progestin pills (P) thus avoiding surgery [

9,

10,

11], considering also that endometriosis seems to poorly worsen in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic women undergoing medical treatment. Among the others, Egekvist

et al. reported that 56% of women with symptomatic rectosigmoid endometriosis avoided surgery using OCs or progestins [

12]. In this setting, levonorgestrel-realizing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) and contraceptive vaginal ring have demonstrated to be viable therapeutic approaches for symptoms related to BE [

13,

14].

It is well known that symptoms of patients with endometriosis do not necessarily correspond to the disease burden [

15] and that severe pelvic pain, chronicity of the disease, side effects of treatment and lack of understanding by other people, can have an impact on the personal, psychological and social aspects of patients’ daily life [

16]. Standing that the decision to operate or to choose a conservative treatment is based mainly on the symptomatology of the patients, it is relevant to have valid tools to assess symptoms severity and quality of life (QoL), such as ‘Endometriosis Health Profile 30’ (EHP-30) [

17], as well as its shorter validated version, the Endometriosis Health Profile-5 (EHP-5) [

18]. Although it is very useful for evaluating the psychological and social aspects of endometriosis, the EHP-30 or EHP-5 do not combine the self-reported QoL with organ-specific symptoms; therefore, other authors have developed a score in order to identify women with Bowel Endometriosis Syndrome (BENS) and to monitor the effect of medical and surgical management of women suffering from BE [

19].

Considering this background, the primary aim of our cross-sectional analysis of a retrospective cohort was to assess the QoL of patients with documented BE managed conservatively (avoiding surgical approach) and to analyze if characteristics of BE nodules (locations, size, degree of stenosis or number of locations) had a different impact on patients’ QoL, intensity of pain symptoms and response to medical therapy. The secondary objective was to compare patients’ QoL according to pre or postmenopausal status and to different medical treatments.

Material and Methods

Study Population

This is a cross-sectional analysis of a cohort of patients with a previous diagnosis of BE performed at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Gynecologic Oncology and Minimally-Invasive Pelvic Surgery, International School of Surgical Anatomy, IRCCS "Sacro Cuore-Don Calabria" Hospital in Negrar di Valpolicella, Verona (Italy) between January 2017 and August 2022. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee (Comitato Etico delle Province di Verona e Rovigo- secondary analysis of Prot. ULTRAPARAMETROENDO I and II-Prog. 3705CESC 09/03/2022). The diagnosis of BE was confirmed by both transvaginal sonography (TVS) and double-contrast barium enema (DCBE). Patients were included in the study if they had been treated conservatively with medical therapy or expectant management and had at least one year of follow-up from the diagnosis of BE. Patients with a history of colorectal surgery (except appendectomy), a previous surgical or radiological diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis, previous bilateral ovariectomy, or psychiatric disorders were excluded. After collecting clinical data and ultrasonographic characteristics of patients at diagnosis, their current clinical situation and menopausal status were assessed through a phone call, during which pain was evaluated by visual analog scale (VAS) and QoL by standardized questionnaires.

Imaging Methods

In our hospital, all double contrast barium enema (DCBE) procedures were performed using a Sireskop SX 40 fluoroscopy system with a motorized table tilt (Siemens AG Medical Engineering, Forchheim, Germany) equipped with Fluorospot T.O.P. imaging system (Siemens AG Medical Engineering, Forchheim, Germany).

The DCBE was not scheduled at a specific phase of the menstrual cycle. Patients were instructed to follow a low-residue diet for 3 days before the examination. On the day before the procedure, patients were given 13 oral tablets of Pursennid (glycosides of senna; Novartis Farma, Naples, Italy) and 15g of magnesium sulfate, followed by 2 L of liquids to minimize dehydration caused by the preparation. In patients suspected of having rectal or rectosigmoid junction endometriosis, a 100% weight-to-volume ratio barium (Prontobario Colon; E-Z-EM, Inc., Westbury, NY) was instilled into the rectum while the patient lay in the left-side-down lateral position. A first lateral view of the rectum was obtained. Once the barium reached the hepatic flexure, the colon was drained by gravity to empty the rectal ampulla of barium while not completely clearing the entire rectosigmoid colon of barium. An anticholinergic agent, hyoscine N-butylbromide, was then used to induce colonic hypotonia. Room air was then gently and intermittently insufflated into the colon. Each colonic segment was viewed in detail on spot radiographs and mid- to high-magnification digital images. Multiple spot films were obtained in all cases, and full-size films of the abdomen (overhead films) were taken in all cases. The procedure lasted an average of 15 minutes.

The images were reviewed by a skilled gastrointestinal radiologist for extrinsic mass effect, kinking, shortening or flattening of the bowel as indirect signs of endometriosis nodules presence. The size of the nodules and degree of stenosis were calculated with a specific radiologic software. The final report showed the number of endometriosis bowel locations, site of locations (rectum, rectosigmoid junction, sigmoid, ileum, cecum, or appendix), dimension of nodules, and degree of stenosis. Ileocaecal and ileal BE detected with DCBE were considered only in the descriptive part of the study and not included in the statistical analysis. This is because of the high risk of intestinal obstruction associated with these types of lesions, treatment was almost always surgical, while the conservative approach was only evaluated in cases of small (less than 2 cm) and asymptomatic nodules [

19,

20].

Ultrasound scans were performed on the same day as the DCBE by examiners (more than 10 years of experience in diagnosing endometriosis) with ultrasound machines (Samsung WS80A Elite) equipped by a wideband 5- to 9-Mhz transducer. Detailed sonographic reports were made, and representative digital images of each patient were saved and stored on a hard drive for subsequent review and analysis.

The ultrasound was performed using a transvaginal approach, while in the case of virgin patients, a transrectal approach was used, both integrated with a trans-abdominal ultrasonography. The ultrasound was performed at any phase of the menstrual cycle, regardless of hormonal therapy. The examination was always performed using a systematic, "step-by-step" approach and describing the sonographic features using terms, definitions, and measurements according to the consensus published by the IDEA group [

21].

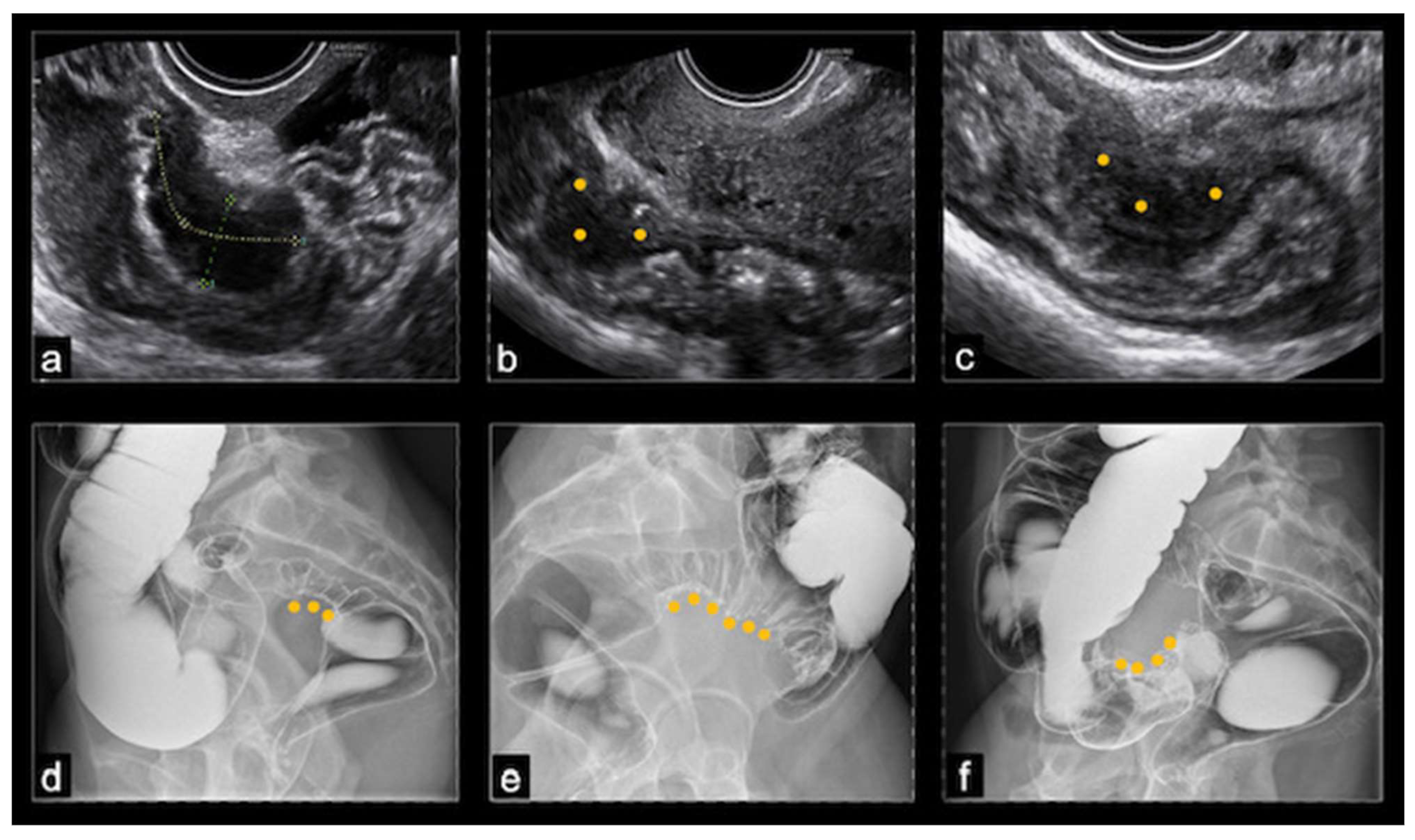

At ultrasound, BE usually appeared as a thickening of the hypoechoic muscularis propria or as hypoechoic nodules with irregular margins, without detectable blood flow at color Doppler. Nodules located above the level of the uterine fundus were considered sigmoid lesions, those located at the level of the uterine fundus were denoted as rectosigmoid junction lesions, and those below this level were considered rectal lesions. The dimensions of the nodules were recorded in three orthogonal planes, but in this study, only the largest measurement was considered. The rising of a nodule towards the lumen of the bowel indicated the possibility of (sub)stenosis. The final nodule dimension was a mean of the dimensions reported by TVS and DCBE, while the degree of stenosis was evaluated only by the DCBE (

Figure 1).

Clinical Symptoms

Pain was assessed using a visual analog scale (VAS) for dysmenorrhea, non-menstrual pelvic pain (NMPP), dyspareunia, dysuria, and dyschezia. A 10-point scale was used, with 1 indicating "no pain" and 10 indicating "the worst imaginable pain."

QoL was collected for all patients using two validated instruments: the Bowel Endometriosis Syndrome (BENS) score and the Endometriosis Health Profile (EHP-5) score. The BENS score is the first endometriosis classification system that is based directly on the patient’s symptomatology, investigating pelvic pain and QoL as well as urinary, sexual, and bowel dysfunction. This tool has been previously shown to be useful in monitoring women with conservatively treated BE. The BENS score is obtained by summing the scores associated with each answer to the 7-item questionnaire. The range of the BENS score (0-28) is divided into three categories: 0-8 (no BENS), 9-16 (minor BENS), and 17-28 (major BENS).

The EHP-5 is a questionnaire developed from the longer, validated EHP-30, to have a brief instrument for measuring health outcomes for women with endometriosis. The EHP-5 is divided into two parts, with questions referring to the previous 4 weeks: a 5-item core questionnaire about pain, control, and powerlessness, emotions, social support, and self-image, and an additional 6-item modular questionnaire about work life, relationship with children, sexual intercourse, medical profession, treatment, and infertility. The response system consists of five levels, ranked in order of severity: ’never’=0, ’rarely’=25, ’sometimes’=50, ’often’=75, and ’always’=100. The modular questionnaire was developed to include items that may not be applicable to every woman with endometriosis. In this study, we chose to consider only the core part of the questionnaire to focus specifically on pain and to reduce the total interview time. In fact, the core part has been shown to be effective in detecting pain intensity compared to other questionnaires [

20]. The responses of the 5-item EHP-5 were summed and transformed according to the EHP-5 manual on a scale from 100 (worst possible QoL) to 0 (best possible QoL).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows V. 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine if the data were Gaussian distributed. For normally distributed data, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were reported. For non-normally distributed data, the median and interquartile range (IQR) were reported. Comparisons between two groups of subjects were performed using the t-test, while for more than two groups, the ANOVA test was used with post-hoc analysis as appropriate. Qualitative data were compared using the Chi-square test. The Kruskal–Wallis test by ranks was used to compare nonparametric continuous and ordinal variables with post-hoc analysis if required. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, after adjusting for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

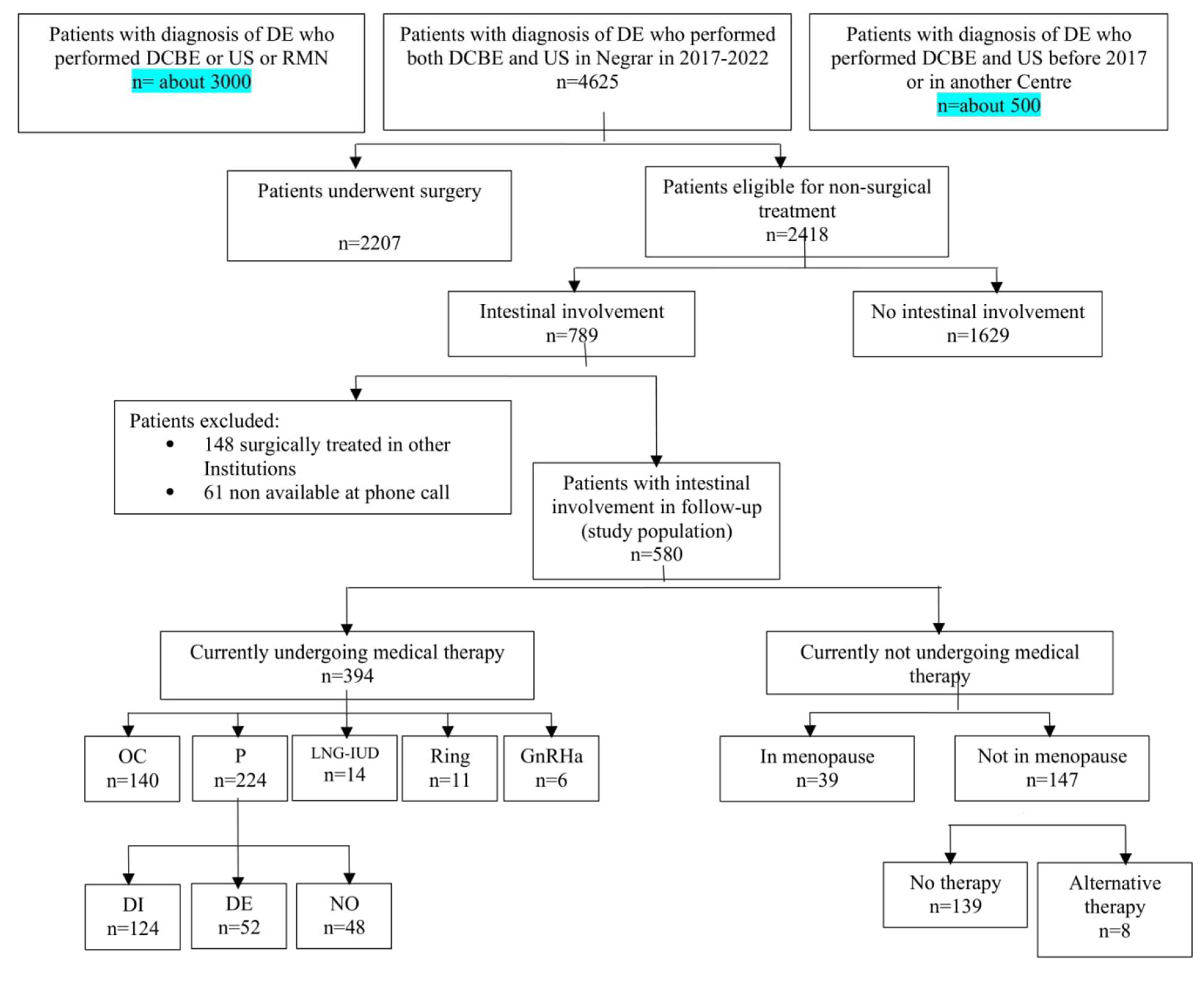

In the period considered in the study analysis, 4,625 women underwent DCBE and TVS as second-level exams for suspected deep endometriosis. Of these, 2,207 (47.7%) had surgical indications and underwent surgery in 47.9% of cases. The remaining 2,418 (52.3%) were considered suitable for a conservative, non-surgical treatment, with 789 (32.6%) of these having suspected intestinal involvement. A flowchart of all patients is shown in

Figure 2.

After the follow-up phone call, it was found that 148 out of 789 patients (18.7%) had undergone surgery for deep endometriosis at other institutions were thus excluded from the study. An additional 61 patients (7.7%) did not answer to the phone call and, therefore, were excluded (

Figure 1).

The final analysis was done on 580 patients who had not undergone any gynecological surgery after a diagnosis of BE performed at imaging. Their characteristics are reported in

Table 1. Among this patients, 302 (52.1%) had no previous endometriosis surgery, 210 (36.2%) had one previous endometriosis surgery, and 68 (11.7%) had two or more endometriosis surgeries in their history. In most cases (95.3%), the previous surgery was not radical and was often performed for diagnostic purposes or was a superficial surgery, such as enucleation of endometriosis cysts. Only 9 patients (3.2%) had a previous bowel resection for deep endometriosis.

Three hundred ninety-four patients (67.9%) were still undergoing hormonal therapy, while 185 (32.1%) were not taking any medical therapy. Of these 185 women, 147 (79.5%) had a residual ovarian activity with regular or irregular menses, while 39 (20.5%) were in menopause. Among patients undergoing therapy, 140 (35.5%) were taking OCs, with a continuous regimen in 86.4% of cases, without a pause between blisters or with a 7-day pause every 4 months. All 224 women (56.8%) in therapy with progestins followed a continuous regimen without a pause.

Quality of Life

Patients included in the study population showed a satisfying overall QoL with a mean (±SD) EHP-5 score of 105.42±99.98 points and a good intestinal function with a mean BENS score of 4.89±5.28. Mean VAS for dysmenorrhea and NMPP was 1.49±2.72 and 2.74±2.23, respectively. A sub-analysis was done in three groups of patients: those of reproductive age under medical therapy, those of reproductive age not undergoing medical therapy, and those of menopausal age (not undergoing medical therapy). The patients of reproductive age not undergoing medical treatment had medical or hematologic contraindications or intolerance to therapy.

Table 2 reported the scores obtained by administering questionnaires on QoL in the whole population and in these three groups of patients.

Patients of reproductive age under medical therapy showed a better QoL in comparison to those of reproductive age without medical therapy concerning intestinal symptoms at BENS (p=0.001), pain (p=0.001), control and powerlessness subdomains (p=0.048) at EHP-5, VAS for dysmenorrhea (p<0.001), dyschezia (p<0.001), dysuria (p=0.032), and NMPP (p=0.002).

Patients of reproductive age under medical therapy showed a worse QoL in comparison to those in menopause not undergoing medical therapy regarding total EHP-5 score (p>0.001), intestinal symptoms at BENS (p=0,06), VAS for dyschezia (p=0.008) and NMPP (p=0.009), and control and powerlessness (p=0.012), social support (p=0.003), self-image (p=0.003) subdomains at EHP-5.

When comparing OCs and progestins in patients under medical therapy, all QoL scores (BENS, EHP-5, and VAS score) were similar except for VAS related to dysmenorrhea, which was significantly better in patients receiving progestins (0.03±0.34 vs 0.83±2.05 points), with not inter-group difference regarding the specific progestin (dienogest, desorgestrel, and norethisterone acetate).

The localization of BE impacted QoL: in particular, sigmoid locations were found to have a lower impact on QoL compared to rectosigmoid nodules for VAS related to dyschezia (p=0.045), NMPP (p=0,007), and control and powerlessness subdomain at EHP-5 (p=0.019). Additionally, VAS for NMPP in sigmoid nodules were found to be lower compared to rectal nodules (P=0.045). Patients with nodules > than 3 cm had a lower mean VAS for dysmenorrhea (p=0.17) and mean BENS score (p=0.021) compared to those with compared to smaller BE nodules. Notably, a mean lower BENS score (p=0.019), emotional well-being subdomain at EHP-5 (p=0.042), VAS for dysmenorrhea (p=0.028) and dyschezia (p=0.047) were also found to be better for patients with evidence of stenosis >30%; otherwise, there were no differences in these scores when comparing patients affected by BE with absence of stenosis and with stenosis between 20 and 30%.

The last comparison was made to evaluate if an impact of characteristics of BE (dimension, location, and stenosis of BE nodules) and intensity of symptoms or between the presence and duration of medical therapy and intensity of symptoms. Among 72 patients with symptoms highly impacting QoL (BENS ≥ 9 and EHP-5 total score ≥ 200), 41 (56.9%) had no stenosis, 21 out (29.2%) had stenosis between 20 and 30%, and 10 (13.9%) had stenosis more than 30% (p=0.03). A post-hoc analysis confirmed that women with no stenosis had worse QoL compared with patients with stenotic nodules (p=0.045). The duration of therapy (more or less than 24 months) did not impact the results evidenced in these three groups of patients. No statistical associations were found regarding duration of therapy or characteristics of BE.

Discussion

BE can present a challenging management for healthcare providers. If it does not cause severe obstruction to fecal transit, surgical intervention may not be the best option as it is associated with a higher rate of ileostomy procedures and potential complications such as suture leakage, rectovaginal fistula formation, anastomosis stenosis, atonic bladder, and

de novo bowel dysfunction, even when the surgery is performed using nerve and vessel sparing techniques [

8,

21,

22,

23]. While conservative approaches such as discoid resection and rectal shaving may lead to fewer complications compared to segmental resection [

24], intermediate and long-term bowel dysfunction, also known as Low Anterior Resection Syndrome (LARS), can still occur [

25]. Additionally, rectal infiltration is often associated with parametrial infiltration, requiring radical surgery with parametrectomy. Even with nerve-sparing approaches, such as the Negrar method, routinely adopted at our institution, the prevalence of LARS remains significant [

8,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Therefore, after the diagnosis of endometriosis, it is important to first evaluate if surgery can be avoided or postponed and to consider it only in cases of severe (sub)occlusive intestinal symptoms, ureteral stenosis with hydroureteronephrosis, presence of large or suspicious adnexal masses or in case of contraindication or poor response to medical therapy [

30].

The current study analyzed VAS for pain and QoL by a validated questionnaire in approximately 600 patients with BE. Regardless of ongoing medical therapy, we found that these patients had a satisfying mean QoL with the absence of relevant intestinal symptoms related to the disease (mean ± SD BENS 4.89±5.28, which is less than 8, the cut-off identified for identifying minor BENS); moreover, a minimal intensity of pain symptoms with subsequent low impact on their daily life (EHP with mean value of 105.42±99.98, and VAS with mean value for each field lower than 3) were observed. This further confirms that the severity of symptoms and endometriosis staging are not necessarily correlated.

An early diagnosis is essential for both asymptomatic patients with BE to prevent the worsening of endometriosis with regular clinical follow-up, and for very symptomatic women who have only adenomyosis or superficial endometriosis, without signs of clear nodules of deep endometriosis. In our study, smaller nodules (less than 3 cm) and nodules not causing significant stenosis (less than 30%) were the most symptomatic. However, this could be a false interpretation of data as it is more likely that larger nodules, when they are painful, would find a surgical indication (and therefore be excluded from the study), while smaller ones are preferably managed conservatively, with medical therapy, at least at the beginning. Moreover, the presence of bowel fixity and angulations associated with BE may worse the symptomatology of patients with smaller nodules and nodules not causing significant stenosis. Basically, this finding may be a further confirmation that many characteristics of bowel nodules (size, degree of stenosis, number of locations) do not impact in terms of QoL or intensity of symptoms, as already suggested in a previous study [

26].

On the other hand, location of BE nodules seems to have clinical relevance: in fact, low (rectal or rectosigmoid) nodules seem to be less tolerated compared to sigmoid nodules, as these patients had worse results for VAS for NMPP, dyschezia, and a more negative psychological impact in daily life (in particular, on lack of control and powerless EHP-5 subdomains). This could be sustained by considering the anatomical spread of endometriosis: when the rectum is involved, it is very common to find the so-called “frozen pelvis” clinical presentation, with deep infiltration of rectovaginal septum, pelvic ligaments, pelvic viscera (uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal ligaments, lateral rectal ligaments, cardinal ligaments, uterus, vagina, etc.) and posterior and lateral pelvic wall, right close to the visceral and somatic pelvic nerves [

27]. This visceral and neural infiltration of the disease or its compressive effect on the pelvic wall are the main cause of neurological pain complained by patients with endometriosis [

31]. Since sigmoid BE can be isolated, without a complete involvement of the posterior compartment, they may have a minor impact on the pelvic innervation and, therefore, cause less pain.

A result of this study, hormonal therapy has proved to be very impactful in terms of QoL. In fact, results show that patients under therapy, compared to those who are not taking any hormonal treatment, have clear better outcomes considering both intestinal function at BENS, pain (pain subdomain at EHP-5, VAS for dysmenorrhea, dyschezia, dysuria and NMPP) and psychological impact (control and powerlessness subdomain at EHP-5). Nowadays, there are several medications available to manage BE, which aim to reduce circulating hormones inducing a pseudo-menopause or a pseudo-pregnancy state, with significant improvement of patient’s QoL. Our study confirms that, in the case of BE, hormonal treatment is recommended, regardless of the dimension of nodules or degree of stenosis, as already suggested by other authors [

30].

There is no treatment that has been demonstrated to be more effective than another, only when dysmenorrhea is the main symptom, progestins result better than OCs (p=0.001), with no differences in QoL among different classes of progestins. In other cases, the right therapy should be found by doctors and patients together, balancing symptom improvement and possible side effects.

When overtime therapy is not effective anymore, it is recommended to try at least one further therapy before considering the failure of medical treatment. This could include changing the class of hormones or the route of administration. Additionally, hormones should not be considered a cure-all, as they may be effective in controlling pain, but continuous long-term therapies are often associated with persistent side effects and the impossibility of obtaining pregnancy, which can negatively impact QoL. In this study, patients in menopause at follow-up after a previous diagnosis of BE had the best QoL, even better than patients of reproductive age under medical therapy. Considering this finding and the potential side effects of treatment, as well as the fact that endometriosis is often associated with an earlier age of menopause, it is reasonable to evaluate the risks and benefits of medical therapy in patients close to menopause, counseling the use of hormones only in the case of a relevant symptoms [

29,

32].

One of the main strengths of this study is the large number of patients in the study population, thanks to the high volume of patients with deep endometriosis who undergo our hospital annually from all over Italy. Over the years, this has significantly improved our accuracy in detecting endometriosis, both with first and second-level exams, allowing for a study on intestinal endometriosis without the need for histological confirmation. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating QoL and treatment compliance based on the characteristics of BE, providing clinicians with greater awareness to successfully treat it outside the operating room.

However, there are some limitations to this study. Retrospective data were used, and symptoms before treatment were collected from clinical notes and asked to patients retrospectively. QoL was recorded only at the time of the phone call, using standardized questionnaires (EHP-5 and BENS). The diagnosis of BE was made with the aid of DCBE and TVS. The major limitation of this study is that it does not consider very symptomatic patients who went directly to surgery or women who did not find relief during medical therapies and were consequently operated on, so we can assume that the population analyzed had an acceptable QoL to decide not to undergo surgery. However, the aim of this study was to evaluate if patients with BE can have satisfactory QoL with conservative management, not to make a comparison between patients who underwent surgery and those who did not, so this limitation becomes less significant.

Conclusions

Among 13,000 to 15,000 patients are annually checked at the IRCCS "Sacro Cuore-Don Calabria" Hospital; of these, about 1500 (~10%) undergo surgery. Even if many patients are operated every year (IRCSS “Sacro Cuore-Don Calabria is a dedicated center that collects the most severe cases from all over the Italy), the majority of women are treated conservatively and this option is offered also in case of infiltrating BE with the aim of avoiding or postponing bowel surgery. Women with BE who do not exhibit (sub)occlusive symptoms associated with a high degree of bowel stenosis do not necessarily require surgery, as they can experience good and lasting QoL regardless of the size, number, or location of nodules. It is crucial to offer medical hormonal therapy to control disease progression and manage pain symptoms, particularly in the case of rectal nodules, which are the most symptomatic. Psychological support is also recommended, especially for patients undergoing long-term medical therapy, as chronic treatment can impact daily life. There is no preferred hormonal therapy for BE, except when dysmenorrhea is the primary symptom, in which case progestins have been associated with better outcomes. Hormonal therapy should be discussed with women close to menopause, with evaluation of risks and benefits. It should be reserved for symptomatic cases as a last resort to avoid surgery while waiting for menopause.

This cross-sectional analysis on a retrospective cohort of patients with BE aimed to reinforce the idea that the “best surgery” for patients with deep endometriosis should be the one that is never performed.

All the centers of care from all over the world with a high volume of surgical patients with endometriosis per year should feel a deep responsibility in order to demonstrate that conservative treatment can be provided in the majority of patients, even in cases involving the bowel. Treatment should be tailored to the patient, not the disease, moving from a lesion-oriented to a patient-oriented approach era.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C. and F.B.; Methodology, S.B. and F.B.; Validation, M.C., F.B. and T.C.; Formal Analysis, S.B. and T.C.; Investigation, F.B.; Resources, M.A.; Data Curation, C.Z.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, S.B.; Writing – Review & Editing, F.B.; Visualization, P.M.; Supervision, G.F.; Project Administration, M.C.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Vieira M, Barakat H, Dousset B, Pansini V, Vacher-Lavenu MC, Dubuisson JB. Anatomical distribution of deeply infiltrating endometriosis: surgical implications and proposition for a classification. Hum Reprod. 2003 Jan;18(1):157-61.

- Abrão MS, Petraglia F, Falcone T, Keckstein J, Osuga Y, Chapron C. Deep endometriosis infiltrating the recto-sigmoid: Critical factors to consider before management. Human Reproduction Update. 2015;21(3):329-39.

- Abrao MS, Andres MP, da Cunha Vieira M, Borrelli GM, Neto JS. Clinical and Sonographic Progression of Bowel Endometriosis: 3-Year Follow-up. Reprod Sci. 2021;28(3):675-82.

- Ferrero S, Moioli M, Dodero D, Barra F. Symptoms of Bowel Endometriosis. In: Ferrero S, Ceccaroni M, editors. Clinical Management of Bowel Endometriosis: From Diagnosis to Treatment. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 33-9.

- Nezhat C, Li A, Falik R, Copeland D, Razavi G, Shakib A, Mihailide C, Bamford H, DiFrancesco L, Tazuke S, Ghanouni P, Rivas H, Nezhat A, Nezhat C, Nezhat F. Bowel endometriosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun;218(6):549-562.

- Remorgida V, Ferrero S, Fulcheri E, Ragni N, Martin DC. Bowel endometriosis: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(7):461-70.

- Biscaldi E, Barra F, Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Ferrero S. Other imaging techniques: Double-contrast barium enema, endoscopic ultrasonography, multidetector CT enema, and computed tomography colonoscopy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;71:64-77.

- Ferrero S, Stabilini C, Barra F, Clarizia R, Roviglione G, Ceccaroni M. Bowel resection for intestinal endometriosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;71:114-28.

- Barra F, Scala C, Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Ferrero S. Long-Term Administration of Dienogest for the Treatment of Pain and Intestinal Symptoms in Patients with Rectosigmoid Endometriosis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(1).

- Leonardo-Pinto JP, Benetti-Pinto CL, Cursino K, Yela DA. Dienogest and deep infiltrating endometriosis: The remission of symptoms is not related to endometriosis nodule remission. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;211:108-11.

- Ferrari S, Persico P, DI Puppo F, Vigano P, Tandoi I, Garavaglia E, Giardina P, Mezzi G, Candiani M. Continuous low-dose oral contraceptive in the treatment of colorectal endometriosis evaluated by rectal endoscopic ultrasonography. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012 Jun;91(6):699-703.

- Egekvist AG, Marinovskij E, Forman A, Kesmodel US, Riiskjaer M, Seyer-Hansen M. Conservative approach to rectosigmoid endometriosis: a cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(6):745-50.

- Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Remorgida V, Scala C, Tafi E, Venturini PL, Ferrero S. Desogestrel-only contraceptive pill versus sequential contraceptive vaginal ring in the treatment of rectovaginal endometriosis infiltrating the rectum: a prospective open-label comparative study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93(3):239-47.

- Gibbons T, Georgiou EX, Cheong YC, Wise MR. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) for symptomatic endometriosis following surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;12(12):CD005072.

- Becker CM, Bokor A, Heikinheimo O, Horne A, Jansen F, Kiesel L, King K, Kvaskoff M, Nap A, Petersen K, Saridogan E, Tomassetti C, van Hanegem N, Vulliemoz N, Vermeulen N; ESHRE Endometriosis Guideline Group. ESHRE guideline: endometriosis. Hum Reprod Open. 2022 Feb 26;2022(2):hoac009.

- De Graaff AA, D’Hooghe TM, Dunselman GA, Dirksen CD, Hummelshoj L; WERF EndoCost Consortium; Simoens S. The significant effect of endometriosis on physical, mental and social wellbeing: results from an international cross-sectional survey. Hum Reprod. 2013 Oct;28(10):2677-85.

- Jenkinson C, Kennedy S, Jones G. Evaluation of the American version of the 30-item Endometriosis Health Profile (EHP-30). Qual Life Res. 2008;17(9):1147-52.

- Jones G, Jenkinson C, Kennedy S. Evaluating the responsiveness of the Endometriosis Health Profile Questionnaire: the EHP-30. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(3):705-13.

- Riiskjaer M, Egekvist AG, Hartwell D, Forman A, Seyer-Hansen M, Kesmodel US. Bowel Endometriosis Syndrome: a new scoring system for pelvic organ dysfunction and quality of life. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(9):1812-8.

- Aubry G, Panel P, Thiollier G, Huchon C, Fauconnier A. Measuring health-related quality of life in women with endometriosis: comparing the clinimetric properties of the Endometriosis Health Profile-5 (EHP-5) and the EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D). Hum Reprod. 2017;32(6):1258-69.

- Balla A, Quaresima S, Subiela JD, Shalaby M, Petrella G, Sileri P. Outcomes after rectosigmoid resection for endometriosis: a systematic literature review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(7):835-47.

- Ruffo G, Scopelliti F, Manzoni A, Sartori A, Rossini R, Ceccaroni M, Minelli L, Crippa S, Partelli S, Falconi M. Long-term outcome after laparoscopic bowel resections for deep infiltrating endometriosis: a single-center experience after 900 cases. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:463058.

- Donnez O, Roman H. Choosing the right surgical technique for deep endometriosis: shaving, disc excision, or bowel resection? Fertility and Sterility. 2017;108(6):931-42.

- Bokor A, Hudelist G, Dobó N, Dauser B, Farella M, Brubel R, Tuech JJ, Roman H. Low anterior resection syndrome following different surgical approaches for low rectal endometriosis: A retrospective multicenter study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021 May;100(5):860-867.

- Ceccaroni M, Clarizia R, Roviglione G. Nerve-sparing Surgery for Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis: Laparoscopic Eradication of Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis with Rectal and Parametrial Resection According to the Negrar Method. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(2):263-4.

- Ceccaroni M, Clarizia R, Bruni F, D’Urso E, Gagliardi ML, Roviglione G, Minelli L, Ruffo G. Nerve-sparing laparoscopic eradication of deep endometriosis with segmental rectal and parametrial resection: the Negrar method. A single-center, prospective, clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2012 Jul;26(7):2029-45.

- Ceccaroni M, Clarizia R, Roviglione G, Ruffo G. Neuro-anatomy of the posterior parametrium and surgical considerations for a nerve-sparing approach in radical pelvic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(11):4386-94.

- Ceccaroni M, Ceccarello M, Clarizia R, Fusco E, Roviglione G, Mautone D, Cavallero C, Orlandi S, Rossini R, Barugola G, Ruffo G. Nerve-sparing laparoscopic disc excision of deep endometriosis involving the bowel: a single-center experience on 371 consecutives cases. Surg Endosc. 2021 Nov;35(11):5991-6000.

- Vercellini P, Sergenti G, Buggio L, Frattaruolo MP, Dridi D, Berlanda N. Advances in the medical management of bowel endometriosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;71:78-99.

- Rossini R, Lisi G, Pesci A, Ceccaroni M, Zamboni G, Gentile I, et al. Depth of Intestinal Wall Infiltration and Clinical Presentation of Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis: Evaluation of 553 Consecutive Cases. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018;28(2):152-6.

- Ceccaroni M, Clarizia R, Alboni C, Ruffo G, Bruni F, Roviglione G, Scioscia M, Peters I, De Placido G, Minelli L. Laparoscopic nerve-sparing transperitoneal approach for endometriosis infiltrating the pelvic wall and somatic nerves: anatomical considerations and surgical technique. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010 Jul;32(6):601-4.

- Ferrero S, Barra F, Leone Roberti Maggiore U. Current and Emerging Therapeutics for the Management of Endometriosis. Drugs. 2018;78(10):995-1012.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).