1. Introduction

The recent WHO report concerning Healthcare workforce in the European region highlights the challenges concerning shortages of healthcare workforce in the region and underscores the need for strategic planning to meet the growing needs of the population and ensure universal health coverage in the region [

1]. Strategic planning for the future of the healthcare workforce extends beyond mere projections; it involves considering optimal numbers, geographic distribution, and competencies desired for the healthcare workforce, as well as coordinating medical education, governmental regulation, and necessary changes in the healthcare system [

1]. Such strategic planning is crucial to address pressing issues concerning healthcare inequalities [

6]. We use the term healthcare inequalities to describe factors affecting the management, access, performance, and experience of healthcare services, as opposed to health outcome inequalities, such as inequality in morbidity and mortality that demand broader considerations related to the social determinants of health [

4,

31].

As the demand for healthcare services continues to rise due to aging populations, chronic diseases, and evolving healthcare needs, it is crucial to anticipate and prepare for future workforce requirements [

1,

2,

39]. Through strategic planning, healthcare systems can forecast demand, assess current and future skill gaps, and implement initiatives to attract, train, and retain healthcare professionals where they are most needed [

2]. This proactive approach works to ensure adequate staffing levels as well as promote equitable distribution of healthcare resources, reducing inequality in access to care [

6]. Moreover, this planning allows for the alignment of workforce development with advancements in technology, changing patient demographics and shifts in care delivery models, thus enabling healthcare organizations to adapt and thrive in an ever-evolving landscape and address concerns of healthcare inequality [

2,

6,

39].

The recent COVID 19 pandemic has served as a testing ground for healthcare workforce planning in the European region, with many countries facing the sudden surge in demand for healthcare workforce with an insufficient, under trained and geographically imbalanced healthcare workforce [

1,

38]. This crisis exacerbated existing shortcomings in the workforce, but also encouraged countries to implement innovative strategies to meet the new demands [

1,

5,

38]. Now, after the pandemic, and with ongoing challenges including the consequences of climate change and its influence on health, especially among vulnerable groups, countries in the region must act to retain this strategic planning and long-term political commitment to healthcare workforce improvement [

5,

32].

Globally there is insufficient strategic healthcare workforce planning informed by an analysis of the health labor market [

1], and therefore the effects of healthcare workforce planning on healthcare inequalities are not sufficiently addressed. In Israel, and several other member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), significant resources have been invested in developing strategic plans to address growing concerns concerning the future of the healthcare workforce, particularly in physician supply and location, and exploring solutions in the context of health inequalities, yet comparative analysis is rare [

16,

17,

20,

22,

24,

27,

33].

2. Materials and Methods

Physicians hold a central position in healthcare systems [

7,

39], and although changing roles and borders between the different health professions are constantly taking place [

34,

39], still the focus on physician healthcare workforce planning is of utmost importance in considering the issue of strategic workforce planning for meeting population needs and reducing healthcare inequalities [

35,

39]. Therefore, we use physicians as a case study for healthcare workforce planning in our paper. Additionally, it's important to consider the constant changes in healthcare modes of delivery such as the development of the position of nurse practitioner (NP), which allows nurses to assume certain responsibilities traditionally held by physicians, thus leading to reduced physician work burden, improved access to healthcare and reduce costs [

8,

39,

41]. Therefore, we will also look at the development and growth of the profession of NP, and its relationship to physician workforce planning, as an example of the need for a broader perspective, that considers developments in healthcare modes of delivery, in healthcare workforce planning [

34,

39].

In this paper we will be reviewing national policy concerning strategic planning of physician workforce in light of healthcare inequalities, with a special focus on Israel, Australia, Germany and Norway. These countries have public healthcare systems capable of formulating strategic plans concerning physician workforce planning in light of projected population needs and healthcare inequalities [

16,

17,

20,

22,

24,

27]. We begin by reviewing government publications, OECD data, and relevant literature, to compile statistics concerning the physician workforce in these countries as compared to countries across the OECD. Through specific measures such as physicians rates (per 1,000 population), the rates of medical school graduates in the country (per 100,000 population), the share of physicians trained abroad out of all physicians, and share of physicians aged 55 and older, we construct a snapshot of physician workforce in these countries, and across the OECD, while highlighting main policy considerations necessary to meet the projected needs of the population and respond to existing healthcare inequalities. We also examine statistics such as practicing nurses' density per 1,000 population and nurse to physician ratio, considering the importance of currently shifting professional boundaries in physician workforce planning. This is especially important in addressing shortages in general practitioners and other primary care specialties [

39,

41].

Additionally, we examine existing healthcare inequalities related to physician workforce through statistics such as reasons for unmet needs in medical care and consultations, medical tests, treatment and follow-ups skipped due to costs.

After this we review government publications concerning strategic plans for physician workforce planning in Israel, Australia, Germany and Norway, while highlighting general trends and main elements in this planning. Here we also bring relevant data from each country concerning the geographical distribution of physicians in the country. There are many terms used when dealing with the geographic distribution of healthcare workforce, and different countries use different categories when describing this measure. Certain countries use the core-periphery paradigm to describe the tension between the underdeveloped peripheral areas, both in the developmental and economic senses, and the much more developed center areas [

13]. Other countries may use the terms urban or metropolitan to allude to more developed areas vs. the terms rural or remote to allude to less developed areas [

14].

Our aim in this review is to outline main elements in strategic workforce planning that can be useful to policy makers in developing plans to address challenges in healthcare workforce planning in light of healthcare inequalities. Strategic planning can enable us to develop a future healthcare workforce that is resilient, sustainable, and capable of meeting the diverse needs of communities while advancing the equity and accessibility of healthcare services [

1,

6].

3. Snapshot of Physician Workforce across the OECD

In our analysis of strategic planning concerning the physician workforce, we have chosen key measures to frame the understanding of current workforce capabilities and projections of upcoming challenges. Physician rates relative to population, with an emphasis on primary physician rates, speak to the current capabilities of the healthcare system and affect population health [

9]. The rate of nurses relative to population, and nurses to physicians, speak to the skill mix in the healthcare system and reflect different ways of care delivery and task distribution [

39]. Healthcare workforce sustainability is a central concern, and the number of medical school graduates per population and percent of physicians aged over 55 speak to the influx and efflux of the population of physicians and future trends in the source of physician workforce [

1]. The share of physicians trained abroad reflects the ability of the national healthcare educational system to supply the population demand and the national reliance on foreign programs that might not meet national standards [

12].

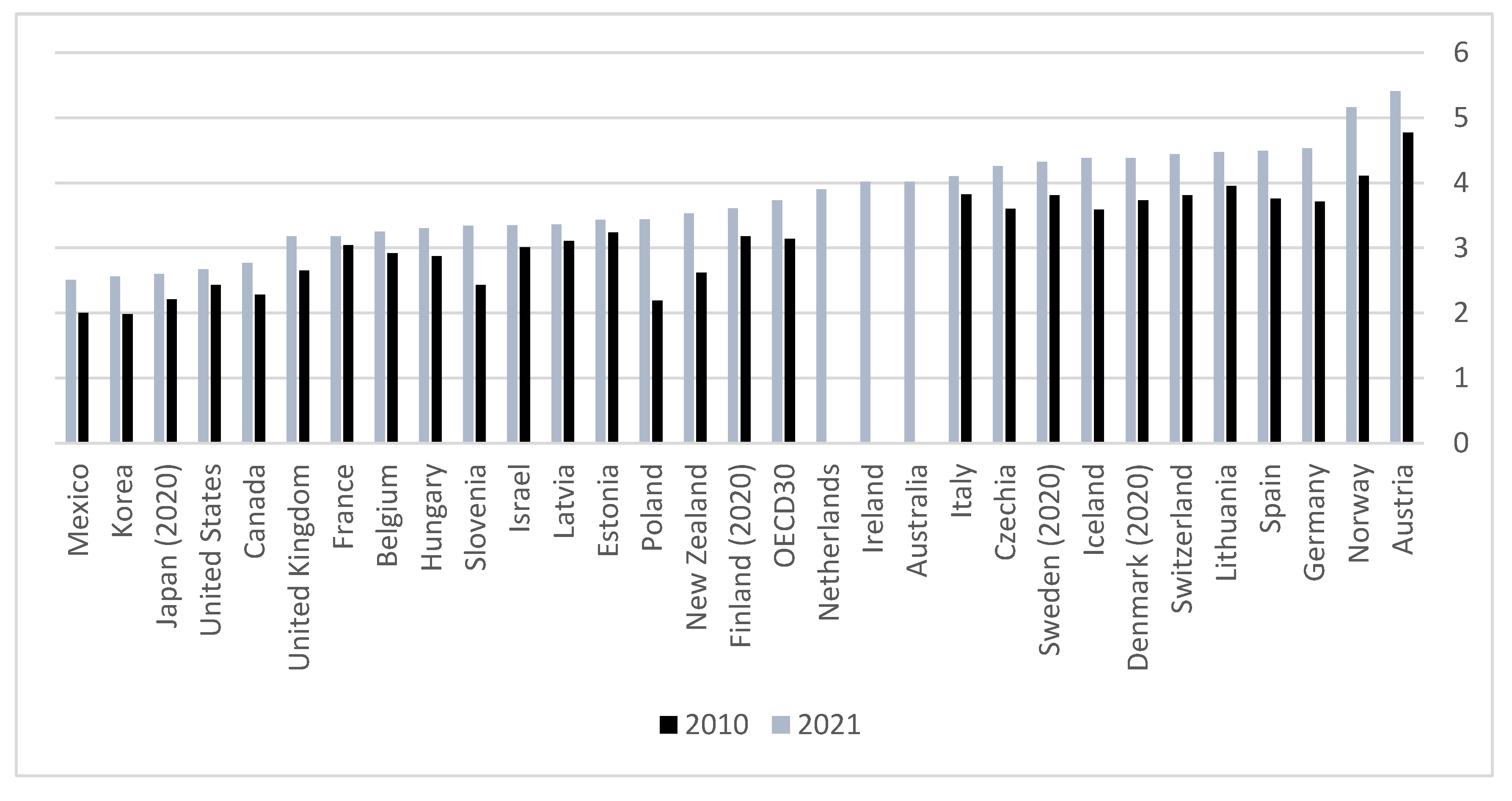

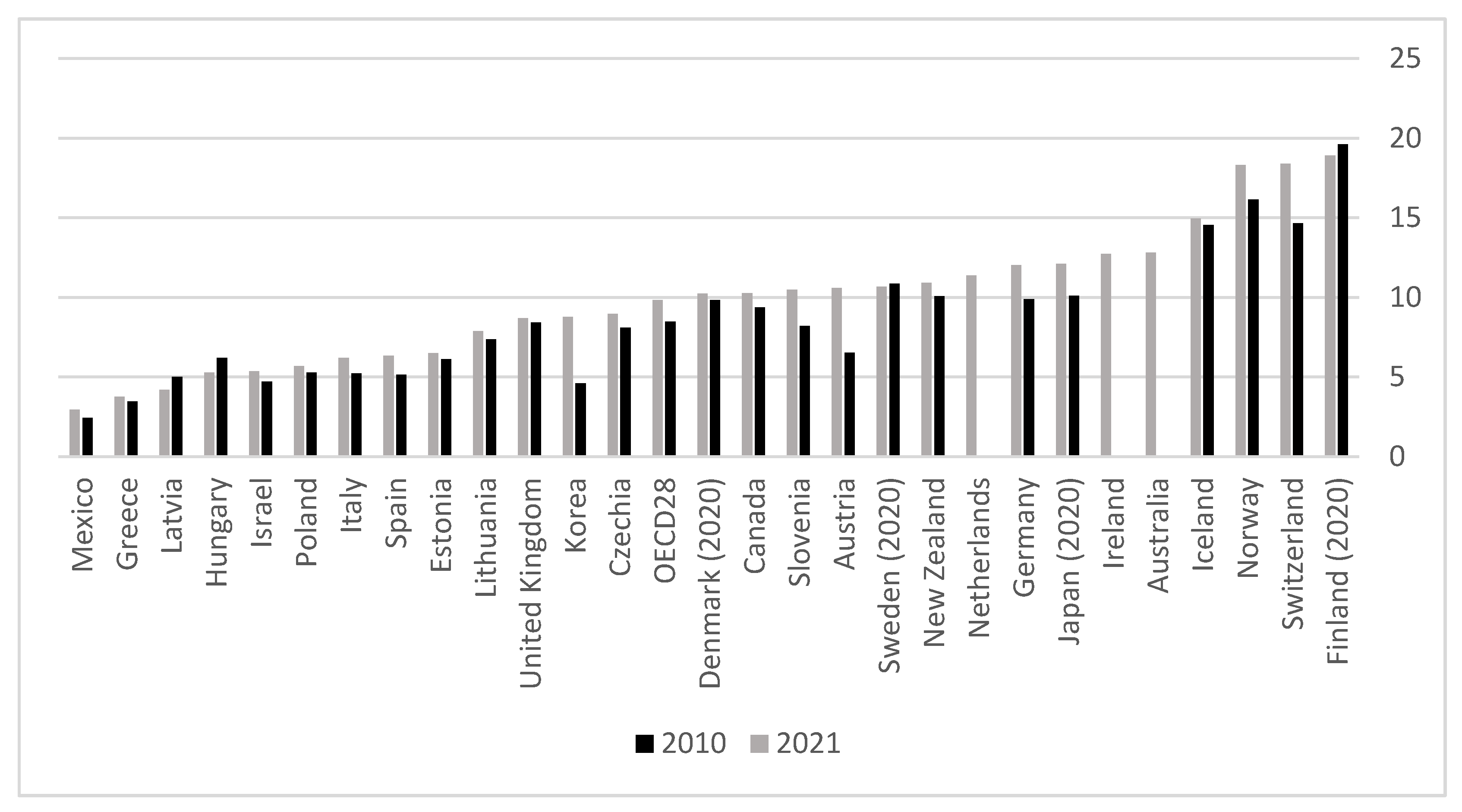

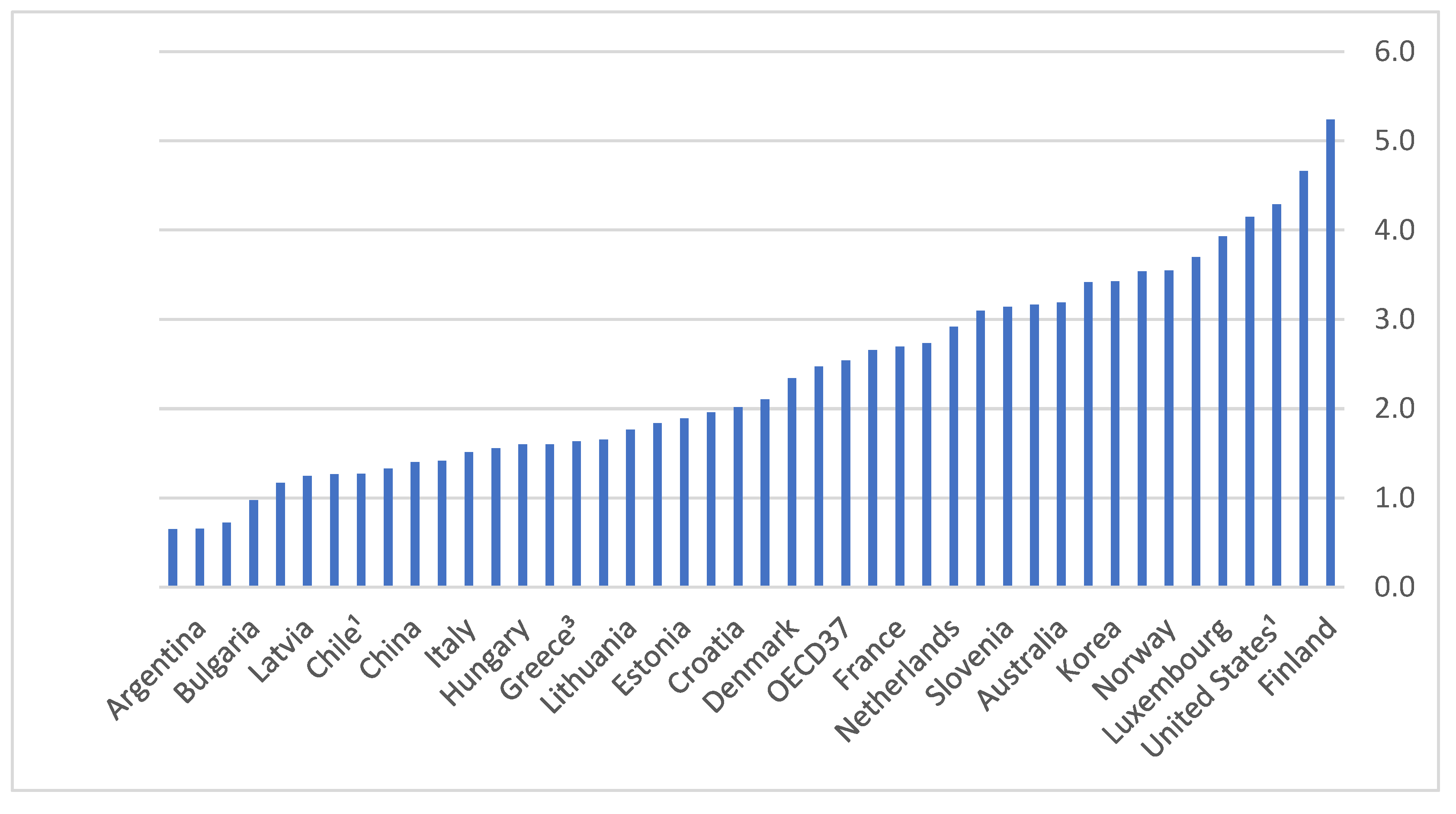

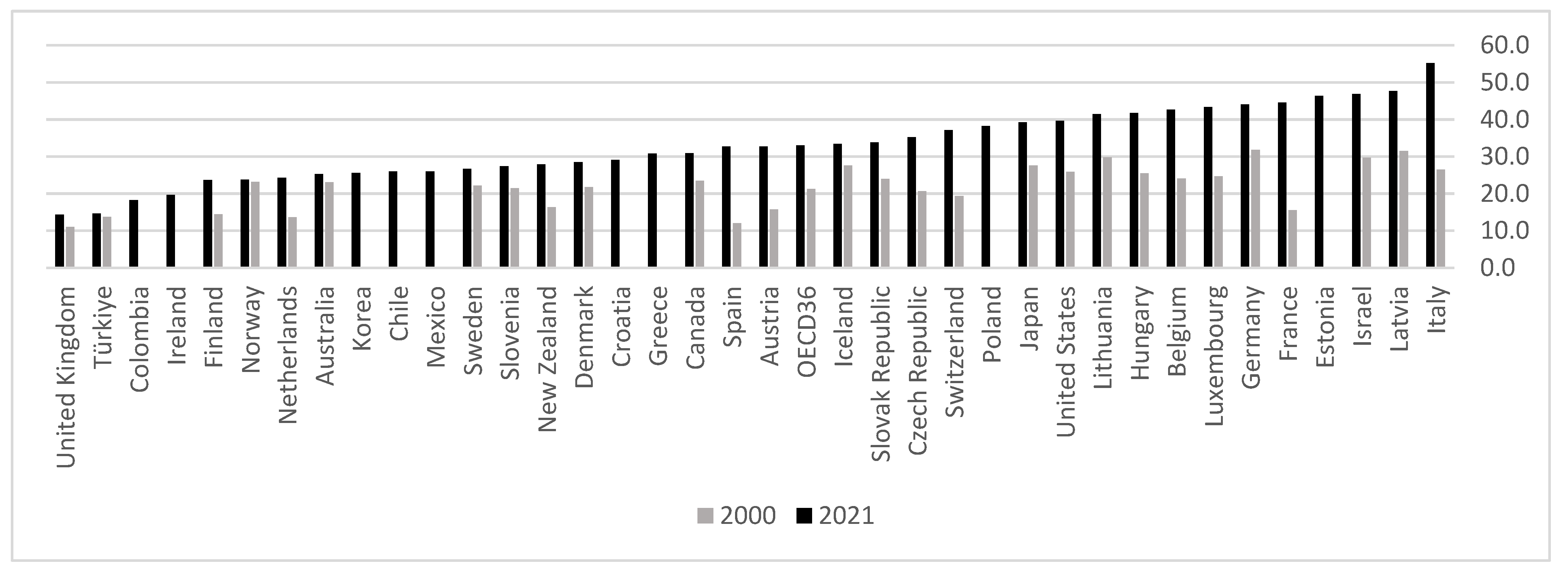

As seen in

Figure 1, the numbers of physicians per 1,000 population vary across countries in the OECD, with a general increase in numbers seen over the years. Concerning the rates of practicing nurses there is a variance across countries both in the rates and in the increase over time, with not all countries managing to increase their rates, as seen in

Figure 2. There is a wide variance concerning the rate of nurses to physicians across countries as well, as seen in

Figure 3.

Currently the rates of physicians and nurses in most OECD countries are higher than in the past and are constantly climbing. Israel has been a notable exception to this trend at times, due to a generally slower increase in physicians and nurses compared to population increase. For example, in 2013 the rates of physicians and nurses in Israel were lower than the rates in 2000 [

39]. The variance in the rates of nurses and skill mix between different countries, shows that some more than others rely on nurses to perform tasks that historically were the prerogative of physicians [

39,

41]. Additionally, the gap between countries concerning the development of advanced nursing roles, such as NP, has been shown to be widening in recent years [

41].

Figure 1.

practicing physicians per 1,000 population. Data source: OECD.

Figure 1.

practicing physicians per 1,000 population. Data source: OECD.

Figure 2.

practicing nurses per 1,000 population. Data source: OECD.

Figure 2.

practicing nurses per 1,000 population. Data source: OECD.

Figure 3.

rate of nurses to physicians. Data source: OECD.

Figure 3.

rate of nurses to physicians. Data source: OECD.

3.1. Foreign Training

In higher-income countries, there tends to be a larger proportion of foreign-trained healthcare workers [

1]. Physicians and nurses who received their training abroad play a significant role in the healthcare professions in several countries, primarily located in northern and western Europe [

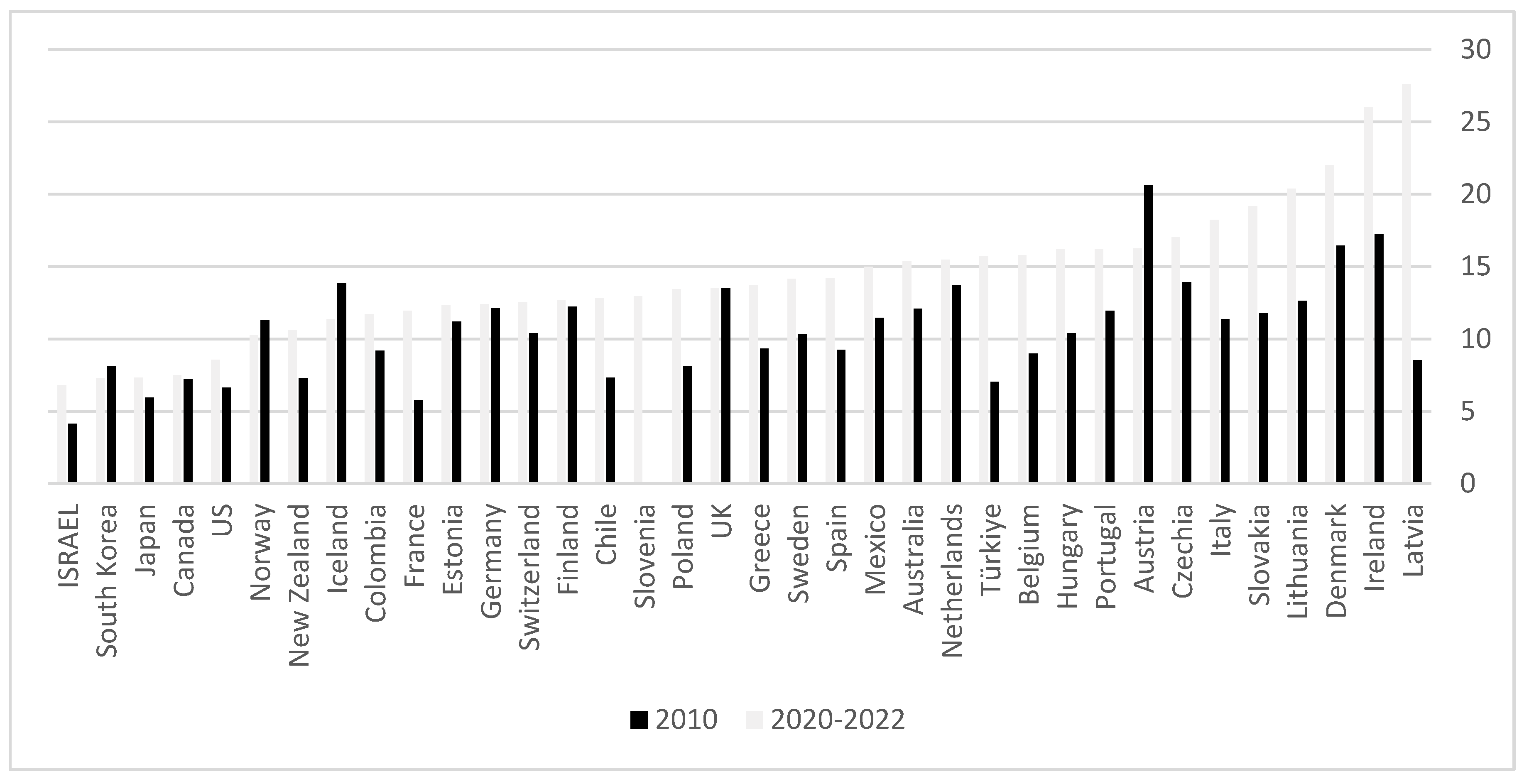

1]. As seen in

Figure 4 there is a wide variance in the share of foreign-trained healthcare workers between countries, with some relying on them for more than half their workforce.

Figure 4.

Share of physicians trained abroad out of all physicians. Data source: OECD.

Figure 4.

Share of physicians trained abroad out of all physicians. Data source: OECD.

Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom were the primary destinations for foreign-trained physicians and nurses in terms of absolute number in 2020. In 2019, the influx of foreign-trained medical physicians entering the healthcare labor market exceeded that of domestic graduates in Ireland, Norway, and Switzerland. This pattern has been observed in various countries since 2010, indicating that international recruitment is becoming an increasingly important source of new HCWs in certain countries, which influences both the receiving and graduating countries [

1].

Within the European Union (EU), freedom of movement and mutual recognition of qualifications for professions like medical physicians, dentists, nurses, midwives, and pharmacists facilitate intraregional mobility. Furthermore, many countries in the Region attract health workers from other countries within and beyond the EU/European Economic Area (EEA). Most foreign-trained professionals in the European Region originate from other EU countries. Some countries, such as Belgium, Germany, and Ireland, serve as both significant sources and destinations for healthcare workers, while others, predominantly located in the south and east of the Region, primarily act as source countries [

1].

Countries gauge intentions to emigrate based on the number of requests for certificates of qualifications, which are necessary for entry into destination countries. However, they do not directly monitor emigration itself, leading to a lack of reliable data on the outflow of HCWs [

1].

3.2. Medical School Graduates

With few exceptions the number of medical school graduates has increased between 2010 and 2020 across the OECD, as seen in

Figure 5.

However, it is important to note that there are many limitations when interpreting data concerning graduates as a source for new recruits in the healthcare labor market (HLM). Not all domestic graduates practice locally, and among those who stay some leave before retirement. This problem can be resolved in different ways, one of which is tracking the geographic location and movements of graduates, but very few countries do so [

1]. Another important aspect, especially when dealing with inequalities, are differences within countries' regions, and across sub-populations. In Israel for example there is a large gap between center and periphery and between Jewish and non-Jewish medical graduates [

22].

3.3. Aging

The aging of healthcare professionals is a significant concern across all WHO Member States, especially in those where a substantial portion of the workforce is 55 years or older, creating a challenge for their eventual replacement upon retirement [

1]. As seen in

Figure 6, the number of countries with a significant percent of physicians aged 55 or older underscores the pressing need for workforce replacement in the upcoming decade.

4. Snapshot of Healthcare Services and Access across the OECD

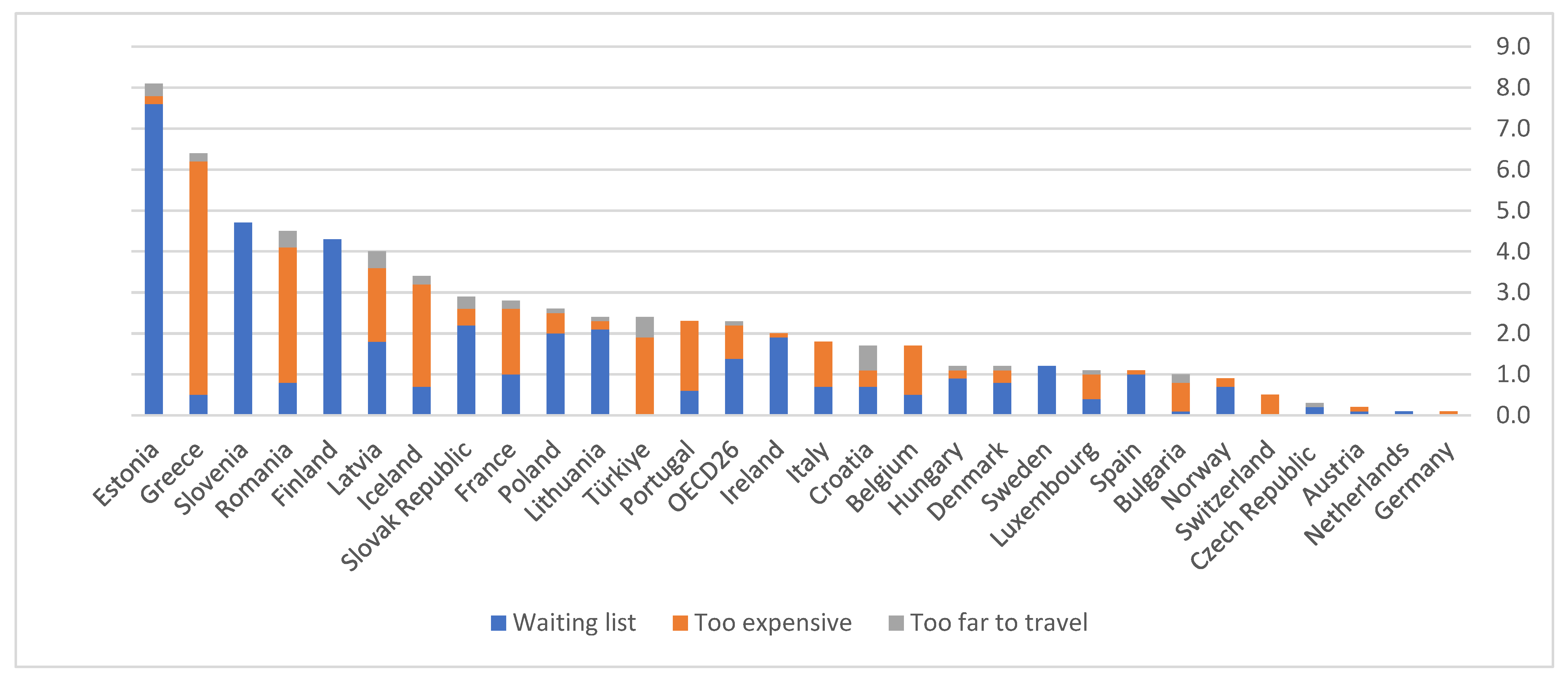

As seen in

Figure 7, length of wait for service is a barrier to accessing medical services across the OECD. The length of waiting time can severely impact healthcare with longer waiting times lowering the quality of medical service, raising the risk of complications and hospitalization, and constituting a burden on the healthcare system as a whole [

15]. Additionally, geographical scarcity of medical personnel, leading to long travel distances, is also a barrier to accessing medical services, as seen in figure 7 as well.

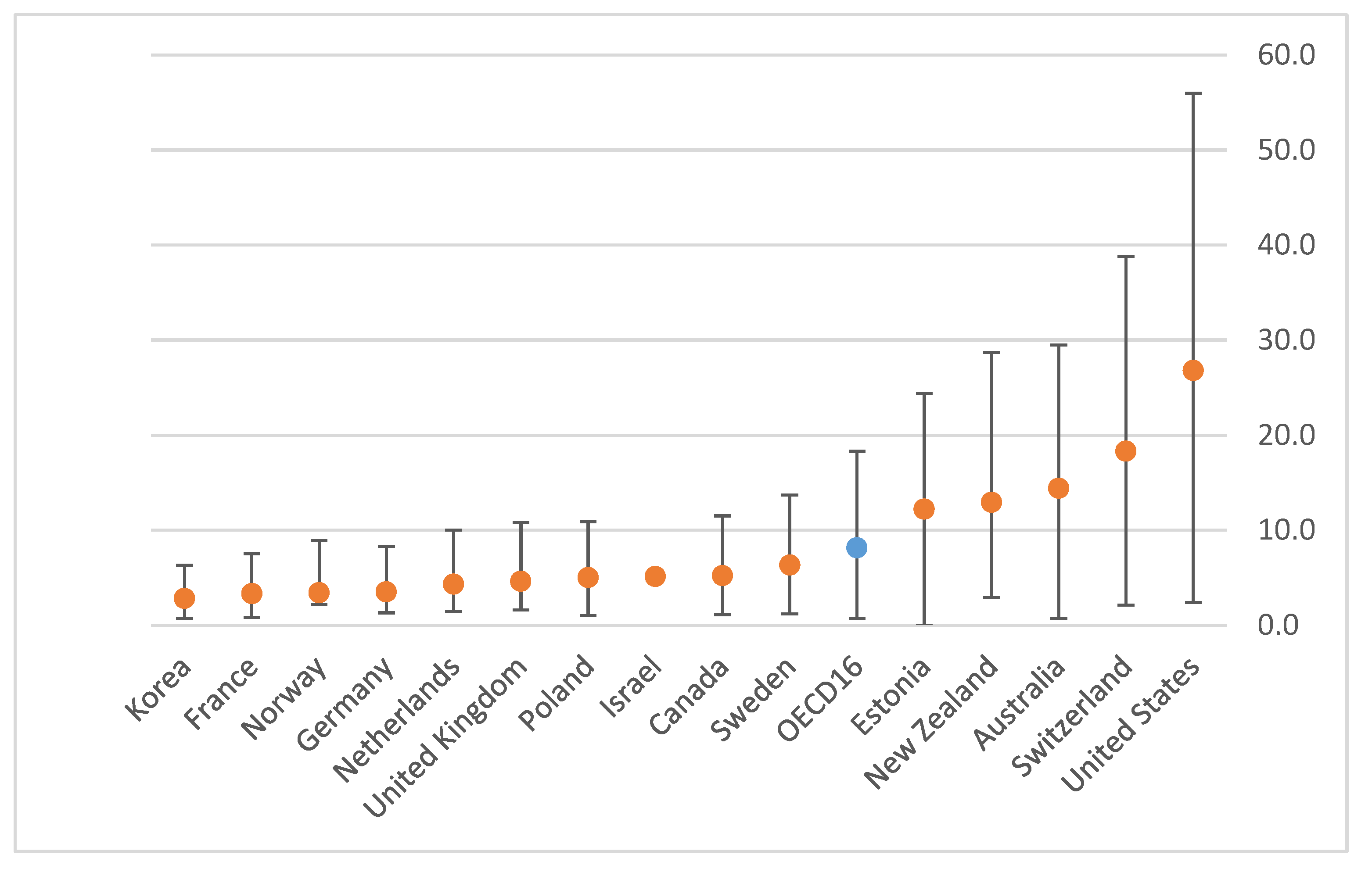

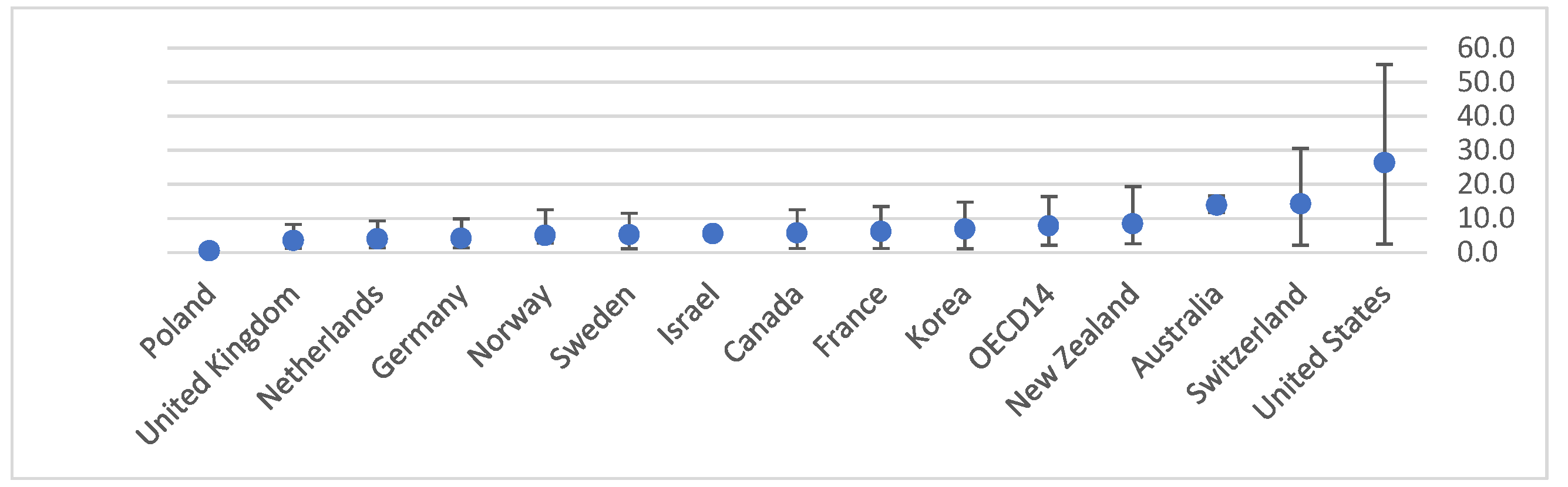

Insufficient access to healthcare services can also be affected by socio-economic factors, with cost of medical services being a barrier to accessing medical services, as seen in

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9. This can lead to areas of insufficient access also in urban settings, in addition to those in rural or remote areas [

1]. Physician workforce distribution affects the availability of health coverage, and insufficient workforce can lead to an increased reliance on the private medical sector and to increased costs [

1].

5. Strategic Physician Workforce Planning in Israel

Despite an increase in the number of physicians over the last decade, Israel still falls about 10% below the OECD average in terms of physicians per 1,000 population [

12]. Israel has experienced a longstanding barrier in the supply of physicians in the country. Although it has doubled the student capacity of the medical education system over the past twenty years, this increase still does not meet the demand of the healthcare system. The demand is due in part, as in most Western countries, to population growth, but most importantly it is attributed to an aging population that necessitates a growing number of physicians to meet escalating care demands, and to the aging of the workforce itself, with nearly half of licensed physicians in Israel aged 55 and over in 2020, indicating a significant replacement need and emphasizing the urgency of training new physicians to offset impending retirements. Although the number of medical graduates from Israeli schools has risen substantially, it remains the lowest relative to population size across all OECD countries [

12,

22].

Israel's physician workforce shortage is distinct from other Western countries due to two main characteristics. The first is the aging of the immigrant population originating in the Soviet Union. During the 1990s there was an immigration wave from the Soviet Union that included many physicians s, thus greatly increasing the physician workforce in a one-time manner. This makes the aging of physicians who immigrated in this wave especially concerning, since there is no expectation for a sudden large influx of physicians to replace them [

28].

The second characteristic is the "Yatziv reform", that went into effect in 2019, which will severely impact the number of physicians joining the workforce after receiving their degree abroad. These physicians have been a significant contributor to workforce growth for many years. As seen in

Figure 4, more than 50% of physicians currently practicing in Israel have obtained their degree out of the country. However, the reform states that all medical students studying in countries that are not part of the OECD will not be able to receive a license in Israel, due to lower standards of medical education. Medical students who started their studies before the reform went into effect are exempt, and therefore the shortage created by nullifying this source of new physicians will be felt mainly from 2026 and onwards. Most students who are currently studying in ineligible countries are men of Arab origin from peripheral areas, many of whom later work in hospitals in the periphery. Therefore, the reform is expected to especially reduce the number of physicians working in the periphery [

12,

22,

27,

28].

In order to deal with the current and projected shortage of physicians, the Israeli Ministry of Health decided to implement a strategic plan based on Australian and Norwegian models of operation. Based on the Australian model, the Israeli Ministry of Health established the "Ilanot" program that subsidizes medical students from the periphery. It has been shown that students born in peripheral areas are more likely to return to practice in those areas at the end of their studies and in the beginning of their internships. Due to this, the Ministry of Health increased the number of spots reserved in peripheral schools, such as Ben Gurion University in Be'er Sheva and Bar Ilan University in Safed, for students who originate in the regions close to these schools. The program includes a full subsidy for the duration of studies with an additional living stipend, under the condition that participents commit to live in the area where the school is located upon graduation, and practice medicine there, for several years [

27].

Due to a variety of factors, it is considered very difficult to sufficiently increase the capacity of the medical education system in Israel so that it alone can meet the growing demands. Therefore, the Ministry of Health has adopted the Norwegian model that allows loans and even full subsidies for medical students who will study abroad and return to Israel upon completion of their studies. The condition for the subsidy or loan is compliance with a study bar set by the ministry and a commitment to work in a specific specialty or hospital experiencing a shortage of physicians, upon the students' return. Israel and Norway face a similar problem concerning the limited capacity of domestic medical education. In Norway, many physicians are locals who had to study abroad, a situation similar to Israel's [

27].

The Financial and Strategic Planning Administration in the Ministry of Health has recently announced another important step in dealing with physician shortage. They have launched a reform in healthcare workforce planning including a number of processes related to acquiring missing data needed for optimal workforce planning. In 2021, the Planning Administration published a statistical model used to forecast future numbers of physicians in Israel, and built a simulator for estimating the effect of policy decisions on the number of medical students based on data from medical schools (Ministry of Health, 2023d). Towards the end of 2022, new regulations were enacted requiring residents to register in the Ministry of Health’s database beginning from January 2023, a measure that contributes significantly to understanding the status of residents and exposing shortages among specialties and across regions [

27,

29]. Recently the recommendations of the subcommittee for determining mechanisms for significant enlargement and national regulation of clinical fields were published. To prevent a lack of capacity for training in clinical fields when increasing the number of medical students, it was recommended to: update the standards for clinical teaching, updating the financial compensation for clinical teaching and managing the allocation of clinical fields on the national level [

43].

According to the 2023 OECD Health System Characteristics survey, the participation of NPs in primary care settings in Israel is currently very limited. However, the survey showed awareness of the importance of expanding their role. The reasons provided for this were the need to address shortages of primary care physicians and wanting to promote career progression and retention among nurses [

42].

6. Strategic Physician Workforce Planning in Germany

Recently the German National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung or KBV in the native tongue), published a paper stating that concerns about manpower shortages have increased due to population aging, including the aging of the physician population. Many older physicians work in remote areas while younger ones prefer urban settings. Therefore, the concern over a shortage caused by a large outflow of physicians includes an additional concern that this will cause a significant imbalance in healthcare services across regions [

16,

18].

The origin of Germany’s healthcare workforce planning can be traced back to the 1990s, with the establishment of a committee tasked with ensuring accessibility to healthcare for all German residents. To accomplish this mission, the committee set out to ensure a proper "physician-patient" ratio in the various regions of Germany [

16,

17]. Their method was based on creating a precise analysis of supply and demand in the field of medicine. Over the years, the method has evolved and undergone several changes until it reached its current form. In addition to the changes the method has undergone, regular updates have been required every two years to adapt to demographic changes [

16,

17].

To ensure maximum accessibility to healthcare services, the committee divided the analysis into two parts: "Supply" (physicians) and "Demand" (population). The combination of the two aims to create a favorable "physician-patient" ratio for all specialties and across all regions. To achieve this, the committee utilized sub-divisions, both of the population and of the physicians [

16,

17].

Firstly, physicians were divided into four sub-groups based on the frequency of their encounters with patients. Accordingly, for each sub group Germany was divided geographically in various ways to express different measurement units for each specialization. The first sub-group is "Family Medicine". Under this group, there is only a category of family physician, and Germany is divided into 883 areas. This multiple division examines supply and demand in geographically small regions to ensure maximum proximity between the family physician and patient. The second sub-group is "General Specialist Medicine" which includes a large number of specializations such as gynecologists, urologists, dermatologists, ophthalmologists, ENT specialists, orthopedists, and pediatricians. Germany was then divided into 361 geographical areas to ensure proximity to patients. The third sub-group is "Specialist Medicine” which includes radiologists, nuclear medicine physicians, child psychiatrists, and internists. For this group, Germany was divided into 97 areas. Finally, the fourth sub-group, "Separate Specialist Physicians", mainly includes physicians who are not required to meet with patients directly, such as nuclear medicine physicians, radiation therapists, human geneticists, laboratory physicians, and more. For this, Germany was divided into only 17 areas. Determining the areas of demand was based on various measures, including current and future demographics, current and future age distribution, existing shortages of physicians, socio-economic structure, geographic aspects including transportation, and more [

16,

17].

The committee's goal is to create the ideal "physician-patient" ratio by adjusting the existing ratio to the one determined according to calculations. In order to perform the adjustment, each area is defined as one of the following: "Open" (contains up to 110% of the required physicians), "Sub-Supply" (contains 50% of the required specialist physicians or 75% of the required family physicians), "Future Sub-Supply" (an area that has not yet been classified as a sub-supply but is expected to be due to age structure for example), and "Closed" (an area with 110% or more of the required physicians). A new physician looking for a place to practice can only choose an area fitting one of the first three options. In addition to directing new physicians to practice in "sub-supply" areas, the committee can also assist by careful examination of the existing physician supply, changing their roles or implementing physician assistants [

16,

17].

The committee includes several experts, including policymakers, physicians, stakeholders, and representatives of the entire population. Each decision the committee makes also receives a predetermined time frame for appeals from various governmental bodies and civil organizations in order to maximize the expression of stakeholders' existing needs [

16,

17].

According to the 2023 OECD Health System Characteristics survey, there are currently no NP roles in primary care settings. However, instituting the position of "community health nurse" is currently being considered [

42].

7. Strategic Physician Workforce Planning in Australia

In Australia, there are no significant differences between states and territories in the number of physicians per 100,000 people, with the notable exception of the Northern Territory. That exception notwithstanding, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) have the largest difference in number of physicians per 100,00, which stands at only 18%. Various states have an internal division of different types of areas, including urban, rural, and even "remote" areas. Using these narrower definitions there are much larger differences in the ratio of physicians per 100,000 [

23].

During 2021, the Australian government issued a strategic plan for the coming decade regarding the medical workforce. This plan was created because the Australian healthcare system has changed and is now dealing with problems that did not exist before. Australia's current problems include an oversupply of physicians and nurses due to professional migration and an unbalanced distribution of personnel between different regions [

24].

Due to the distribution problem, the Australian government has called for the creation of a comprehensive plan including collaboration with all hospitals and medical schools in the country. This plan includes several action pathways, out of which we will focus on the two main ones. The first is creating a data-based infrastructure for supply and demand. The plan proposes to establish a human resources planning body composed of representatives from a large number of organizations and stakeholders related to the field of medical care. This body will be responsible for the data infrastructure related to medical supply and demand across the country, so that it can present a detailed, data based, picture to all levels involved (clinics, hospitals, medical schools, specialty areas, etc.). This body will identify shortages or surpluses in various areas and coordinate problem management among stakeholders [

24].

The second action pathway deals directly with the current imbalance in the distribution of personnel, which leads to a shortage of family physicians, a higher number of personnel in urban areas compared to remote areas, and a large number of temporary workers compared to permanent workers. To address these problems, several actions related to different populations are proposed. For student populations, increasing the number of specialists in fields experiencing shortages, including family medicine, is suggested. This increase will be achieved by creating a "traffic light" system for specialties in demand, so that students will be able to choose their field of specialization only according to the system. Additionally, the increase will be facilitated by career advisors working in the different schools to expose students to specialties they were previously unaware of. Lastly, barriers to specialization in rural areas need to be removed and incentives increased to encourage more students to assist in addressing inequality. Regarding physicians who migrated, or are temporarily in the country, the plan proposes establishing a body to monitor their numbers and ensure they are directed to practice in areas with greater need [

24].

The Australian government is working to narrow the gaps in physician availability by intervening in the composition of the existing student body in schools. Since 2011, the Australian Parliament has stipulated that 25% of medical students must come from rural backgrounds. The rationale being that individuals from rural backgrounds would be more inclined to return and work in their communities upon completion of their studies. Despite Parliament's efforts, there has been no significant increase in the number of physicians practicing in rural areas [

25]. In 2019, the body of Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand (MDANZ) published a paper describing the position of medical schools on the issue of physician distribution in the country. According to their claim, a third of enrolled students in the beginning of their training express a willingness to work in rural communities, yet after six years of school their decision does not hold. Several reasons were described as drivers for this phenomenon. Firstly, most students find a life partner during their school years and settle down in an environment close to school, which typically means an urban environment. Secondly, the professional connections they begin to form are also centered around their school and affiliated hospital. Thirdly, there are few opportunities in rural areas to develop in research or teaching, so that physicians who aspire to do so usually return to cities. In their paper MDANZ argue that there is a need to strengthen the connection between students and rural communities throughout their school period, through the creation of a learning network with remote communities [

26].

Additionally, the Australian government has recently released a national 10-year plan for increasing the number of NPs in order to help address healthcare inequalities. This plan includes four actions themes: improving awareness of NP services, increasing the scope of NP services, supporting NPs in realizing the full scope of their practice and working to increase NP workforce. Among the actions listed in the plan is incorporating NPs in strategic healthcare workforce planning aiming to meet population needs [

42].

8. Strategic Physician Workforce Planning in Norway

While many countries grapple with a shortage of physicians, Norway faces a different issue: a sizable influx of physicians, yet an uneven distribution across regions and medical specialties. Despite this influx, a significant portion of medical graduates in Norway are actually from foreign institutions. Due to a shortage of medical school capacity domestically, many Norwegians pursue their medical education abroad with state-funded scholarships. Upon completion, they return home for their internship. However, national committees have observed disparities in the quality of education between domestic and foreign institutions. Differences in familiarity with the Norwegian healthcare system and language barriers often hinder practical patient experience for those with foreign education, placing them at a disadvantage compared to their domestically educated counterparts [

19,

20,

21].

To address this, increasing the proportion of medical students trained within Norway's borders from approximately 60% currently to 80% has been proposed. This involves expanding existing medical school capacities across the country and introducing a specialized program exclusively for Norwegian students who completed their first three years of medical studies abroad. This program would allow them to seamlessly integrate into Norwegian medical education for the remainder of their training [

19,

20,

21].

However, despite many efforts to increase the number of physicians in Norway, market forces and physician preferences still result in an uneven distribution across regions and medical specialties. Family medicine stands out prominently among medical specialties facing shortages. This particular field contends with a scarcity of practitioners, exacerbated by high attrition rates among young physicians and a geographically uneven distribution of professionals [

30].

Regional disparities in access to General Practitioners (GPs) are evident, particularly in rural areas and smaller municipalities. By the end of 2018, nine municipalities, six of them in Northern Norway, reported no GPs available. In three counties—Finnmark, Nordland, and Møre & Romsdal—persistent vacancies in GP positions have left 2–4% of their populations without access to a GP for an extended period [

30].

Furthermore, a Commonwealth Fund survey conducted in 2017 across several countries, including Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the USA, revealed that the proportion of respondents aged 65 and above reporting a wait of two or more days to access a GP was higher in Norway compared to the average of other nations (53% vs. 38% on average) [

30].

In 2020, the Ministry of Health and Welfare in Norway released a report aiming to devise a strategy for bolstering the presence of family physicians across various regions. The report outlined several key recommendations to address this objective. Firstly, it proposed the provision of financial grants to novice physicians during their initial two years of practice, particularly targeting those who opt to work in areas with populations of fewer than 5,000 people. This initiative seeks to support physicians during the early stages of their careers when their patient base may be limited and their income insufficient to cover expenses [

30].

Secondly, the report advocated for a revision of the tariff system to enhance clarity for both patients and physicians. By streamlining the tariff structure, the aim is to create a more transparent and accessible framework for healthcare services [

20].

Additionally, the report emphasized the need for more enticing employment agreements in municipalities experiencing challenges in physician recruitment. These agreements would offer broader support, including certifications, expanded guidance beyond statutory requirements, regular networking opportunities for intern physicians, and financial assistance for practices serving small patient volumes. This comprehensive approach aims to address recruitment challenges at both individual and community levels [

20].

A common challenge in Norway is that in areas with few physicians, family physicians assume a large scope of tasks. Tasks that are usually the responsibility of other specialists are performed by family physicians and therefore the scope of their work is significantly increased. In response to this, the report highlighted the need to reduce the scope of tasks undertaken by family physicians in those areas. To ensure that family physicians focus on their designated responsibilities, the government intends to monitor and regulate the tasks they perform [

20].

Finally, the report underscored the importance of teamwork among family physicians to effectively manage the increasing number of patients with chronic conditions. By promoting collaborative work among medical teams, the government aims to enhance efficiency and effectiveness in treating patients with multiple chronic ailments, leveraging the collective Expertise and resources available within the healthcare system [

20].

According to the 2023 OECD Health System Characteristics survey, the scope of practice of NPs in the country is relatively broad. The survey further indicated a high awareness concerning the importance of expanding NPs roles in primary care setting. The main reasons cited for this being the need to promote better access in primary care settings and promoting continuity and quality of care [

42].

9. Discussion

As elaborated in previous sections, Israel, Germany, Australia, and Norway each have a comprehensive strategic plan for physician workforce [

16,

17,

20,

22,

24,

27]. While these plans differ in many ways certain key points and challenges emerge, as seen in

Table 1,

Table 2. From this, and from the general literature reviewed in this paper, Four main themes emerge concerning strategic planning for physician workforce:

Data based forecasting of medical care supply and demand, achieved through a wide collaboration of stakeholders.

Considering the changing boundaries of health professions, with an emphasis on the nursing workforce, while conducting physician workforce forecasting.

Increasing the number of medical graduates, preferably domestically trained, but also foreign trained as needed.

Reducing the uneven distribution of physician workforce between regions and specialties, with a special emphasis on general practitioners such as family physicians and rural, remote, or peripheral areas.

Drawing from these plans, and from the different reports dealing with the subject of strategic healthcare workforce planning [

1,

12,

38,

39,

40], several policy recommendations to improve strategic planning for the physician workforce can be formulated, with an emphasis on their role in reducing health inequalities:

Improving mechanisms for data supported, supply and demand based, physician workforce planning: Promoting a structured work method that entails creating models and databases to be used for workforce planning and which strengthen the link between workforce planning and policy formulation [

12,

27,

38]. Towards this goal, a designated governmental body dealing with healthcare workforce planning can be established. The responsibilities of this body include collecting relevant information for the evaluation of medical supply and demand, publishing current forecasts of future needs, and evaluating the implications for medical training frameworks [

12].

Alternatively, the Dutch model may be considered. This model includes establishing an independent non-governmental advisory body, similar to the Dutch Advisory Council on Medical Manpower Planning (ACMMP), in which central stakeholders (such as professional associations, medical schools, health funds, and more) will collaborate in an equal partnership. Working jointly, they will formulate predictions concerning the workforce, update these predictions and present recommendations to the government concerning the necessary number of medical students. Adopting this model requires conducting a cost-benefit analysis, defining the proposed organization’s structure, defining the various roles of stakeholders in such a way that a balance of power is maintained, and defining the relations with governmental agencies [

12].

Restructuring medical education to align with population needs and the requirements of the healthcare systems: Updating the educational curriculum and promoting the accreditation of medical education centers. This needs to be done in such a way that the physicians of tomorrow will receive the necessary training to meet emerging challenges and to supply the increased demand in specific fields such as mental health, geriatrics, palliative care, etc. [

1,

39].

Increasing the number of domestically trained medical students: Increasing the capacity of existing domestic medical schools to accept new candidates, while also considering opening additional medical schools as needed. A common problem in this field is the limited capacity of clinical training frameworks in hospitals. Therefore, it is recommended to expand clinical rotations and increase total training capacity, through methods such as increasing the quantity of shifts that include clinical training, increasing the size of training groups, and establishing clinical rotations in out of hospital frameworks (such as community based primary care institutions and public health institutions). A critical component of this is including sufficient budgets for teaching staff and additional teaching hours [

12,

39].

Encouraging the return of medical students studying abroad: Offering financial assistance to students studying in foreign medical schools which meet predefined standards of medical education, under the condition that they return after the completion of their studies and work in geographic areas and professional fields of national preference. This measure is supplementary to increasing the number of domestic medical school students, serving as a source for increasing the number of medical graduates despite possible limitations of the domestic training system [

12].

Defining a standardized method for managing residency programs and placement of candidates: Creating a central system to manage residency programs, using estimates based on workforce forecasts to decide the number of available positions. Another important measure is ensuring that there be a designated budget for the different residency programs, allocated based on the quantity and type of residency positions offered, to avoid reliance on the hospitals’ general budget resulting in low wages and difficult working conditions for residents [

12].

Utilizing strategies to recruit new physicians, and retain current physicians, in areas facing current or projected shortages: Acting to reduce the burden of care on physicians in underserved areas by reducing clinical teaching hours, delegating tasks to other healthcare professionals, such as nurses, and incentivizing physicians practicing in those areas by providing monetary benefits and work hour flexibility [

1,

39]. Another important measure is increasing the number of medical students intending to practice in underserved areas and fields when they finish their training, by providing academic priority and monetary support for them during medical school [

1,

12,

39].

Moving toward a multi-professional approach in healthcare workforce planning: In order to better respond to population needs, improve access to healthcare and reduce costs, forecasting models need to assess the impact of changing healthcare delivery models in an integrated way [

39]. This is especially important in the field of primary care which commonly faces shortages, and in which different healthcare professions, with an emphasis on the nursing workforce, have been shown to contribute to reducing physician work burden when their scope of practice was increased [

38,

39].

There are several additional factors that should be considered when conducting strategic planning for the physician workforce. One such factor is the recent uptake in the use of digital health tools that support the healthcare workforce and reduce their work burden [

1]. Shifting towards a greater implementation of digital tools, both in healthcare delivery and in workforce training is recommended [

1] and can affect both healthcare quality and increase healthcare access to remote and rural areas [

39] . Another factor to be considered is the importance of fitting the process of knowledge transfer to the local context. Policy frameworks developed in other countries and settings may not take into consideration unique local characteristics, and the knowledge transfer process must take this into account to succeed [

36]. Finally, when implementing strategies to retain physicians in the workforce, especially in underserved areas, it is important to act to maintain a skilled workforce [

37,

39]. Focusing solely on workforce quantity can lead to impaired care and ultimately burden the healthcare system [

37].

10. Conclusions

Strategic planning for the future of the physician workforce in high income countries in the European region must take into account a myriad of factors concerning the optimal development of the workforce, the necessary coordination between healthcare, education and governmental systems, and its effects on health care inequalities. Major challenges facing policy makers in conducting such strategic planning include issues such as the aging of the physician workforce, the capacity of the medical educational system to train new physicians and the total number of domestic medical students, the ratio of foreign trained physicians and the effects this has on the standard of care, workforce gaps between different regions and areas and the effect of changing roles and borders between health professions. To address these challenges, we suggest several key strategies learned from existing strategic plans in Israel, Germany, Australia, and Norway, while being careful to highlight the need to fit them to the local context.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to conceptualization and methodology. Resources, Gonen, O'; writing, both the original draft preparation and to review and editing, Lev, N'. Leeman, H'; supervision, Davidovitch, N'. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

data is available by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. (2022). Health and care workforce in Europe: Time to act. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe.

- World Health Organization. (2016). Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/250368.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Retention of the health workforce in rural and remote areas: A systematic review. Geneva: World Health Organization; Human Resources for Health Observer Series No. 25.

- Ford, J., Sowden, S., Olivera, J., Bambra, C., Gimson, A., Aldridge, R., & Brayne, C. (2021). Transforming health systems to reduce health inequalities. Future Healthcare Journal, 8(2), e204–e209. [CrossRef]

- Ziemann, M. , Chen, C., Forman, R., Sagan, A., & Pittman, P. (2023). Global Health Workforce responses to address the COVID-19 pandemic: What policies and practices to recruit, retain, reskill, and support health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic should inform future workforce development? European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK594085/.

- Pittman, P., Chen, C., Erikson, C., Salsberg, E., Luo, Q., Vichare, A., Batra, S., & Burke, G. (2021). Health Workforce for Health Equity. Medical Care, 59(Suppl 5), S405–S408. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis, J.-L., & van Gestel, N. (2016). Medical physicians in healthcare leadership: Theoretical and practical challenges. BMC Health Services Research, 16 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), 158. [CrossRef]

- Htay, M., & Whitehead, D. (2021). The effectiveness of the role of advanced nurse practitioners compared to physician-led or usual care: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances, 3, 100034. [CrossRef]

- Starfield, B., Shi, L., Grover, A., & Macinko, J. (2005). The effects of specialist supply on populations’ health: Assessing the evidence. Health Affairs (Project Hope), Suppl Web Exclusives, W5-97-W5-107. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2020). Norway health system review. WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/443398/Norway-Hit-oct2020-rev.pdf.

- Skudal, K. E. , Garratt, A. M., Eriksson, B., & Leinonen, T. (2016). Psychometric properties of the Nordic Patient Experiences Questionnaire (NORPEQ): Patient safety culture in Norwegian nursing homes. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 30(2), 280–285. [CrossRef]

- Lafortune, G. , Dedet, G., Balestat, G., Gellie, V., Turatto, F., Dagistan, E., & Slenter, V. (2023). OECD Report on Medical Education and Training in Israel, OECD. https://search.oecd.org/health/OECD-report-on-medical-education-and-training-in-Israel.pdf.

- Pugh, R. , & Dubois, A. (2021). Peripheries within economic geography: Four “problems” and the road ahead of us. Journal of Rural Studies, 87, 267–275. [CrossRef]

- Hart, L. G., Larson, E. H., & Lishner, D. M. (2005). Rural definitions for health policy and research. American Journal of Public Health, 95(7), 1149–1155. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, D. , & Chow, C. K. (2020). Waiting Time as an Indicator for Health Services Under Strain: A Narrative Review. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 57, 004695802091030. [CrossRef]

-

Regionale Verteilung der Ärzte in der vertragsärztlichen Versorgung. (n.d.). KBV - Region; Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV). Retrieved March 31, 2024, from https://gesundheitsdaten.kbv.de/cms/html/16402.php.

-

Bedarfsplanung. (n.d.). KBV - Bedarfsplanung; Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV). Retrieved March 31, 2024, from https://www.kbv.de/html/bedarfsplanung.php.

-

Arztzeit-Mangel. (2023, June 21). KBV - Arztzeit-Mangel; Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV). https://www.kbv.de/html/themen_38343.php.

- Kunnskapsdepartementet. 2022. Muligheter og kostnader ved økning av utdanningskapasiteten i medisin [Rapport]. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/muligheter-og-kostnader-ved-okning-av-utdanningskapasiteten-i-medisin/id2912736/.

- Omsorgsdepartementet. (2020, May 11). Handlingsplan for allmennlegetjenesten 2020-2024; Attraktiv, kvalitetssikker og teambasert [Plan]. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/handlingsplan-for-allmennlegetjenesten/id2701926/.

- Helsedirektoratet. 2020. Leger i Kommunene Og Spesialisthelsetjenesten. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/leger-i-kommune-og-spesialisthelsetjenesten/Leger%20i%20kommunene%20og%20spesialisthelsetjenesten%20-%20rapport%202020.pdf/_/attachment/inline/9bcf5459-80e6-4716-ab00-1766ee0cc0db:ac1f2b4e2a8216bf8aa6246e843249ffc49721db/Leger%20i%20kommunene%20og%20spesialisthelsetjenesten%20-%20rapport%202020.pdf.

- Ministry of Health (2022). Health inequalities and dealing with them 2021. Ministry of Health. https://www.gov.il/he/departments/publications/reports/inequality-2021-n.

- Australian Government department of health and aged care. (2019). Medical practitioners. https://hwd.health.gov.au/resources/publications/factsheet-mdcl-2019.pdf.

- Australian Government department of health and aged care. (2022). National Medical Workforce Strategy. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2022/03/national-medical-workforce-strategy-2021-2031.pdf.

- the Senate Community Affairs Committee Secretariat. (2012). The factors affecting the supply of health services and medical professionals in rural areas (pp. 83–104). https://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/senate/community_affairs/completed_inquiries/2010-13/rurhlth/report/~/media/wopapub/senate/committee/clac_ctte/completed_inquiries/2010-13/rur_hlth/report/report.ashx.

- Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand. (2019, October). Policy proposal: Medical schools’ contribution to addressing the medical workforce shortage in regional and rural Australia. https://medicaldeans.org.au/md/2020/01/2019-Oct_Policy-proposal_Rural-Medical-Workforce_MDANZ_FINAL.pdf.

- Ministry of Health. (2023). Healthcare workforce reform: Ministry of Health policy in response to the shortage of physicians in Israel and strengthening the Negev and the Galil. Ministry of Health. https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/reports/health-human-resources-reform-n/he/files_publications_units_financial-strategic-planning_publications_man-power_health-human-resources-reform.pdf.

- Ministry of Health. (n.d.). New Physicians 2023 Summary. Ministry of Health. https://www.gov.il/he/Departments/publications/reports/the-new-physicians-2023.

- Davidovitch, N., Lev, N., & Levi, B. (n.d.). The Healthcare System in Israel: Between the NewNormal and the OldNormal. Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel. https://www.taubcenter.org.il/en/research/healthcare-between-new-and-old/.

- Saunes, I. , Karanikolos, M., & Sagan, A. (2020). Norway: Health system review (Health Systems in Transition). https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/331786/HiT-22-1-2020-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- Chelak, K. , & Chakole, S. (2023). The Role of Social Determinants of Health in Promoting Health Equality: A Narrative Review. Cureus, 15(1), e33425. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, C. , & Muchira, J. (2023). Climate Change. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice, 50(4), 645–655. [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, E. , Denis, J.-L., Côté, N., Lotta, G., & Neri, S. (2023). Comparing Health Workforce Policy during a Major Global Health Crisis: A Critical Conceptual Debate and International Empirical Investigation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- Nancarrow, S. A. , & Borthwick, A. M. (2005). Dynamic professional boundaries in the healthcare workforce. Sociology of Health & Illness, 27(7), 897–919. [CrossRef]

- Bourcier, D. , Collins, B. W., Tanya, S. M., Basu, M., Sayal, A. P., Moolla, S., Dong, A., Balas, M., Molcak, H., & Punchhi, G. (2022). Modernising physician resource planning: A national interactive web platform for Canadian medical trainees. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 116. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, T. , Czabanowska, K., & Schröder-Bäck, P. (2024). What is context in knowledge translation? Results of a systematic scoping review. Health Research Policy and Systems, 22(1), 52. [CrossRef]

- Abelsen, B. , Strasser, R., Heaney, D., Berggren, P., Sigurðsson, S., Brandstorp, H., Wakegijig, J., Forsling, N., Moody-Corbett, P., Akearok, G. H., Mason, A., Savage, C., & Nicoll, P. (2020). Plan, recruit, retain: A framework for local healthcare organizations to achieve a stable remote rural workforce. Human Resources for Health, 18(1), 63. [CrossRef]

- Ready for the Next Crisis? Investing in Health System Resilience. (2023). OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2016). Health Workforce Policies in OECD Countries: Right Jobs, Right Skills, Right Places. OECD. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2019), Health in the 21st Century: Putting Data to Work for Stronger Health Systems, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Delamaire, M. and G. Lafortune (2010), "Nurses in Advanced Roles: A Description and Evaluation of Experiences in 12 Developed Countries", OECD Health Working Papers, No. 54, OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Australian Government department of Health and Aged Care (2023), Nurse Practitioner Workforce Plan. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-05/nurse-practitioner-workforce-plan.pdf.

- Ministry of health. (2024). The Committee for Addressing the Medical Manpower Shortage in the Health System; the subcommittee for determining mechanisms for significant enlargement and national regulation of clinical fields. https://www.gov.il/he/pages/the-committee-dealing-shortage-medical-personnel-health-system.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).