1. Introduction

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCLs) are a heterogeneous group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that mainly affect older adults with an incidence of 7.5 per one million people annually. This kind of malignancy starts with mutated T cells that infiltrate into the skin and alter cell interactions in the microenvironment and surrounding skin cells too [

1,

2].

The different subtypes of CTCL are characterised by high variability in both clinical and genetic features. The most frequent one is Mycosis fungoides (MF), which represents 55% of CTCL cases, while Sézary syndrome (SS), its leukemic variant, is only 5% of CTCL cases, but is considered the most aggressive CTCL subtype [

1,

2,

3]. MF clinical development goes through patches, plaques, and tumours, compromising the immunological system and even other organs in the tumour stage. Meanwhile, SS is a very aggressive subtype with a high recurrence rate and poor prognosis, going through erythroderma, and lymphadenopathy, and it is associated with neoplastic clonal T-cells in the skin, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood [

2,

3,

4].

There is a wide variety of available therapies such as topical corticosteroids, ultraviolet phototherapy, radiotherapy, total skin electron beam therapy, chemotherapy, and antibodies such as mechlorethamine or bexarotene [

2,

5]. However, the only curative treatment available is allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) [

6].

As mentioned before, MF and SS start with the monoclonal proliferation of effector/central memory CD4+ T-cells growing under an inflammatory landscape. Crucial for the CTCL progression are the interactions that T cells establish with the skin microenvironment, leading to advanced stages and an immune-suppression state with increased risk for infections and decreased antitumour immune response [

2,

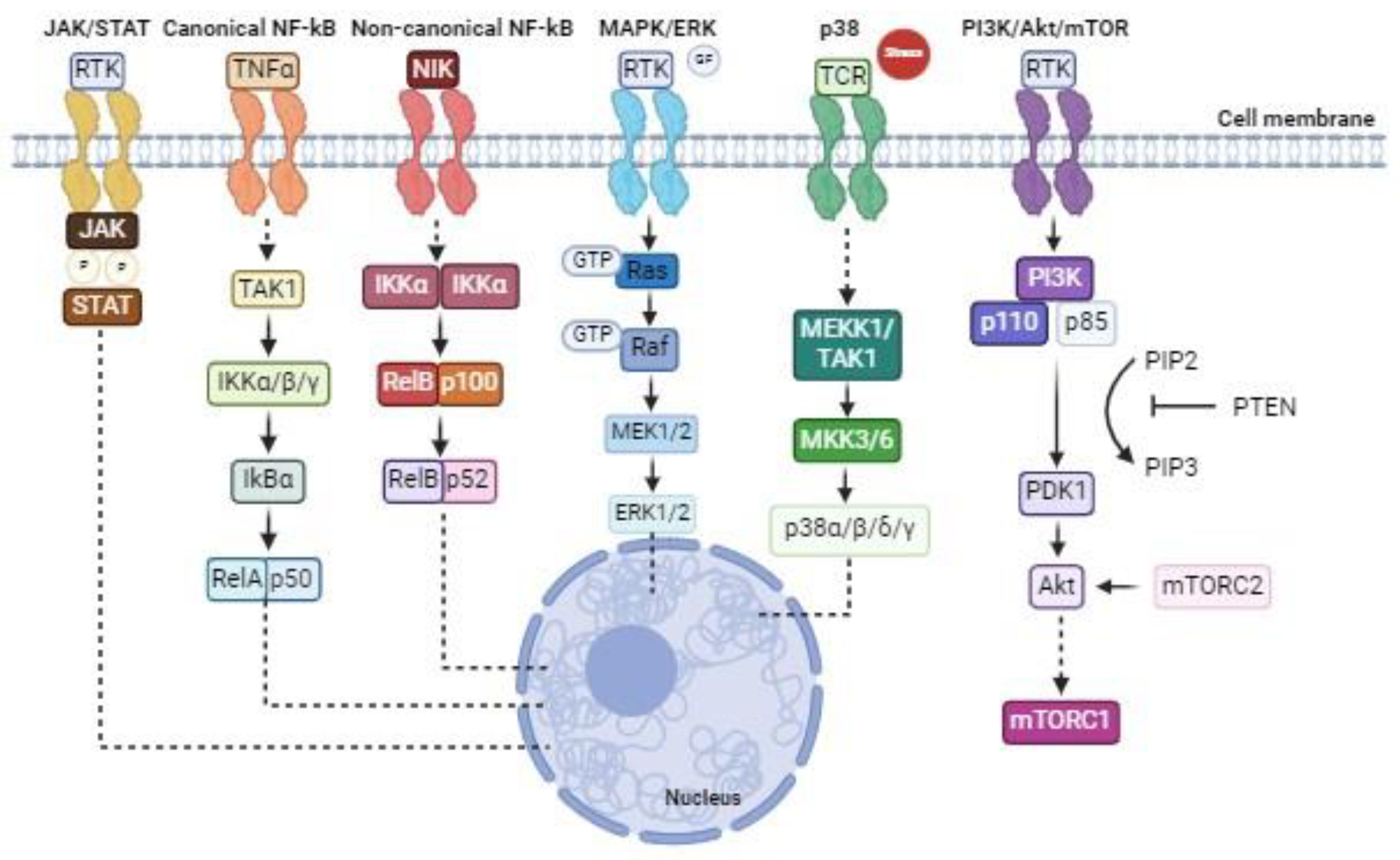

3]. These cell-to-cell interactions are carried out by different signalling networks like JAK/STAT, MAPK/ERK, PI3K/Akt, and NF-kB, among other signalling pathways. For CTCL initiation and progression, there are indeed dysregulations of these key cell pathways that are fundamental for cell viability. Thus, alterations will promote T-cell malignancy, immune response deregulation, and microenvironment remodelling [

2].

Due to the variety that characterises the different CTCL subtypes and the relevance of the cell pathways alteration during tumour progression, becomes clear the importance of acquiring a more targeted approach and direct treatments towards the players of these key pro-tumorigenic pathways. Therefore, this review will focus on different approaches to precisely inhibit the kinases of each cited signalling as therapeutic opportunities (

Figure 1).

2. JAK/STAT Signalling

The JAK/STAT pathway is one of the key cellular signalling pathways involved in the regulation of proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, immune regulation, and haematopoiesis by controlling gene expression [

7,

8]. Ligands such as cytokines, hormones, and growth factors by interacting with their receptors, can trigger this pathway, whose main components are JAKs (Janus Kinases) and STATs (Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription). JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2 (non-receptor Protein Tyrosine Kinase-2) are protein kinases that can be activated upon ligand-mediated receptor multimerization that allows the JAKs trans-phosphorylation; once activated, they phosphorylate their targets STATs. STATs consist of seven cytoplasmic transcription factors (STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5a, STAT5b, STAT6). When they are phosphorylated, they can dimerise, enter the nucleus, and regulate gene transcription by binding specific regulatory sequences [

7].

Alteration of the JAK/STAT signalling pathway has been involved in the pathogenesis of solid tumours and haematological malignancies, including CTCLs. Point mutations in JAK1, JAK3, STAT3, and STAT5b and copy number variants (CNVs) in JAK2, STAT3, and STAT5b have been observed in CTCLs, and these mutations can vary in the different subtypes of this malignancy [

2]. The CNVs in JAK2, STAT3, and STAT5b and activating mutations in JAK1 and JAK3 are more typical of SS. In MF is quite frequent the downregulation of SOCS1, a direct inhibitor of JAKs; can occur because of deletion/unbalanced translocation (35%), the upregulation of the SOCS1-targeting miR-155 or the methylation of its promoter [

3,

9]. Hyperactivation of the JAK/STAT signalling in CTCL can be due to both genetic alterations of the pathway’s elements in the tumour cells and increased stimulation operated by interferons and cytokines, like IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15, typical of the inflammatory microenvironment that characterises this type of cancer. This supports T-cell survival by affecting proliferation, apoptosis, and immunogenicity [

3,

7]. In particular, the early stage of CTCL is usually characterised by constitutive STAT4/5 activation induced by cytokines, while advanced stages are defined by cytokine-independent JAK1 and JAK3 constitutive signalling [

10]. STAT3 and STAT5 constitutive expressions support the upregulation of Th2 cytokine IL-4, miR-155, survival genes like BCL2 and BCL-XL, and cell cycle genes like Cyclin D and c-Myc [

11].

2.1. JAK Inhibitors

Because of the central role of the JAK/STAT pathway in the pathophysiology of CTCLs, specific approaches against its proteins have been studied, including JAK inhibitors. JAK inhibitors act on the four JAKs preventing the activation of the STAT-gene expression regulation [

12]. Pacitinib, Filogotinib, and Oclacitinib can target specific JAKs, like JAK1, or be less specific like Baricitinib, Abrocitinib and Ruxolitinib that target JAK1 and 2, or Tofacitinib that targets JAK1, 2 and 3; and a multikinase inhibitor, Perficitinib, that can inhibit all the JAKs [

2]. Based on how they bind and interact with the JAKs, they can be distinguished into reversible or irreversible, and ATP-competitive or allosteric inhibitors [

12].

Thanks to their anti-inflammatory action, JAK inhibitors are now FDA-approved for dermatological diseases, graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD), ulcerative colitis, myelofibrosis, and rheumatoid arthritis [

2]. In recent years, different

in vitro,

in vivo and clinical studies investigated the effect of JAK inhibitors in CTCLs, showing promising results.

2.2. JAK Inhibitors Effect on Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis in CTCL In Vitro Models

Ruxolitinib, a JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor, and Tofacitinib, a JAK3 inhibitor (with minor action towards JAK1 and JAK2 too) have been tested in different CTCL cell lines, with more data available concerning Ruxolitinib effects in vitro and in vivo.

It has been shown that both Tofacitinib and Ruxolitinib induce a cytotoxic effect in MyLa, SeAx, HH, and Hut-78 cells; Tofacitinib was more effective in Hut-78 cells that carried a JAK3 mutation [

11,

13]. Reduction in cell viability has been observed in both MyLa and SeAx cells treated with Ruxolitinib, with a consistent major decrease if combined with the histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi) Resminostat [

11,

14]. Yumeen et al. studied the effect of Ruxolitinib JAK’s inhibition in patient-derived cells too, and they observed variation between patient samples and a moderate correlation between high levels of JAK2 expression and the sensitivity to Ruxolitinib. Importantly, they assessed that JAK inhibition effects were potentiated when combined with HDACi, proteasome, and BET inhibitor, but the best results were obtained if combined with BCL2 inhibitor [

15].

It has been further demonstrated that Ruxolitinib inhibits cell proliferation in MyLa, SeAx, HuT-78, and HH [

11,

16,

17]; again, it was observed that its effect is amplified if combined with Resminostat in MyLa and SeAx cells [

17]. A recently identified JAK inhibitor, ND-16 (Nilotinib derivate), showed a similar result as Ruxolitinib in inducing cell cycle arrest in H9 cells [

18].

In addition, Ruxolitinib enhances apoptosis in SeAx and MyLa cells, but this effect becomes statistically significant only if used in combination with Resminostat [

11,

14,

17]. ND-16 was proved to increase the apoptotic process in H9 cells too [

18].

2.3. JAK Inhibitors Interfere with Pro-Tumorigenic Cellular Signalling In Vitro and In Vivo CTCL Models

When CTCL cells are treated with JAK inhibitors, not only STATs are contrasted, but key pro-tumorigenic signalling is perturbed. MyLa, HuT-78, and HH cells decrease STAT3 expression under Ruxolitinib treatment [

16]. It has been evaluated that MyLa cells present lower levels of p-STAT3 after 48 hours of treatment [

11]. Even ND-16, in H9 cells, decreases STAT levels and regulates cell cycle proteins and the Bcl-2 family members [

18]. This has been also confirmed

in vivo: analysis in CTCL CAM (chorioallantoic membrane) tumours proved that even MyLa and SeAx xenografted tumours treated with the dual treatment Ruxolitinib and Resminostat inhibited STAT5 phosphorylation [

14].

2.4. JAK Inhibitors Block Primary Tumour Formation and the Metastatic Cascade in CTCL

Ruxolitinib also exerts anti-tumour activity and blocks the metastatic cascade at different levels; again, these effects are increased if combined with Resminostat [

14]. The CAM model has been exploited to study Ruxolitinib potential

in vivo and allowed first to assess that it can decrease the size of primary xenograft tumours of MyLa and SeAx cells, with statistically significant results in the SeAx ones. Nevertheless, Ruxolitinib also inhibits both migration and invasion potential of SeAx cells; in MyLa cells, the same effect is observed but only if combined with the HDACi, and the dual inhibition tested in 3D spheroids dramatically reduced the number of escaped CTCL cells and their travelled distance. Going along the next metastatic steps, JAK inhibition by Ruxolitinib also decreased SeAx cell intravasation in the CAM model, while it is not able to decrease the number of extravasated cells and colonisation capability alone. However, it reduces liver and lung metastasis in both MyLa and SeAx-derived models.

2.5. Clinical Trials and Case Reports of JAK Inhibitors in CTCL

Recently, Vahabi et al. reported all the clinical trials, case reports, and case series that evaluated the efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in the treatment of CTCL [

2]. Two non-randomized phase II clinical trials have been conducted, one tested Ruxolitinib in T-cell lymphomas and one Cerdulatinib in refractory/relapsed CTCL or PTCL (Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma) patients. Cerdulatinib is a dual SYK/JAK inhibitor, precisely it targets JAK1, 2, and 3, but also the tyrosine-protein kinase (SYK). SYK has been found overexpressed in T-cell lymphomas and identified as a key factor in driving cell growth and survival [

19]. Cerdulatinib-treated patients showed better overall response rate (ORR = 35%) compared to Ruxolitinib-treated ones (ORR=11%); nevertheless, both clinical trials revealed variable ORR depending on the CTCL subtype. Indeed, between those treated with Cerdulatinib, the highest ORR was reached by the MF patients, while the lowest was by SS ones. Considering Ruxolitinib, the subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) patients were the best responders, showing a clinical benefit rate (CBR) of 100% [

2]. Vahabi et al. also took into consideration eight case reports and three case series of Ruxolitinib and Upadacitinib (JAK1 inhibitor) treatments in CTCL patients that confirmed higher effectiveness in SPTCL.

For what concerns the safety profile of JAK inhibitors in CTCL patients, the adverse effects that emerged as most common were neutropenia and infections, though they are manageable. However, Vahabi et al. suggested caution in their administration to old patients with a history of cardiac disease, since studies conducted on JAK inhibitor use in other inflammatory diseases reported increased risk for cardiovascular events, as well as cancer, and infection. Moreover, it is emerging that JAK inhibitor treatment is responsible for de novo CTCL development or relapse in those patients with underlying autoimmune disease or prior immunosuppression. Indeed, patients treated with JAK inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis with an immunosuppressive history developed de novo CTCL, and two CTCL patients who underwent Ruxolitinib for chronic GVHD worsened [

2].

2.6. JAK Inhibition to Overcome Staphylococcus aureus-induced drug resistance

Staphylococcus aureus infections are quite common in SS patients, and it has been recently demonstrated that it is responsible for inducing drug resistance in these patients. Staphylococcal enterotoxins (SE) protect malignant T cells from HDACi, while chemotherapeutic drugs and metabolic inhibitors induce cell death. Interestingly, JAK/STAT signalling is one of the driving pathways of this process, and its inhibition through Tofacitinib can block the SE-induced Romidepsin (HDACi) resistance [

20]. Thus, JAK inhibitors could be potentially used to overcome the

S. aureus-induced drug resistance.

3. NF-kB Signalling

Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB) is a key genetic transcription regulator involved in inflammation, immune response, and cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation. The NF-kB family is composed of five members: p65 (RelA), RelB, C-Rel, p50 (p105/NFkB1), and p52 (p100/NFkB2). They form homo- or hetero-dimers that are maintained inactive in the cytosol through the binding to the inhibitory IkB proteins; in the case of p105 and p100 proteins, their C-terminal IkB-like structure is enough to maintain them inhibited. The NF-kB activation occurs thanks to the phosphorylation of the IkB proteins by the IkB kinase (IKK) complex (IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ) that initiates their ubiquitination and so degradation. The free NF-kB dimers can translocate into the nucleus and bind and regulate their target genes. In the canonical pathway, pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF, IL-1) and TLR ligands (e.g. liposaccharides) allow the p50-RelA/p65 freeing through the activation of IKKβ. In the so-called “non-canonical” pathway, LT, BAFF, CD40, and RANKL activate the IKKα homodimers, and the NF-kB dimers released are composed by p52 and RelB [

21,

22,

23]. In both activation pathways, TRAFs (TNF receptor-associated factors) are involved, and while RIPs (receptor-interacting proteins) and TAK1 cooperate with them in the canonical pathway to activate IKK, NIK is responsible for phosphorylating and activating IKKα in the non-canonical one upon TRAFs regulation [

22,

24].

Most of the human cancers and leukaemia are characterised by constitutively activated NF-kB [

21]. High levels of NF-kB signalling support T-cell proliferation, activation, and survival, and aberrant NF-kB pathways are associated with lymphoma development [

3,

22]. In CTCLs, the increased NF-kB functionality is a key driver of malignant cell survival and inflammatory signalling through the induction of anti-apoptotic and pro-inflammatory genes. In addition, in more advanced stages of CTCL progression, increased expression of immunosuppressive genes, like

IL-10 and

TGFB, are responsible for the immunosuppression response [

21]. This is particularly true in SS, which is characterised by constitutively increased NF-kB activity. Moreover, heterozygous deletions, somatic mutations, truncation, CNVs, and splice site mutations in NF-kB pathway players have been identified in CTCL [

10].

Therefore, it is evident the importance of this pathway as a therapeutic target in CTCLs. Bortezomib, which blocks the IkB proteasomal degradation maintaining NF-kB dimers inactivated in the cytosol, is now the main approach studied in CTCL to inhibit the NF-kB signalling, with positive results coming from a phase II study [

25]. Nevertheless, two different kinases are crucial for NF-kB activation and could be directly targeted.

3.1. IKK Inhibitors

IKK activation represents the key step of NF-kB activation, thus this kinase could be pharmacologically targeted. IKKβ selective inhibitors have been the main focus of modulating abnormal NF-kB signalling, however, the lack of clinically positive results led to a reduced interest in the pharmaceutical industry. So, it has been proposed to redirect the interest towards IKKα inhibitors to understand even better if there are peculiar advantages in inhibiting the specific IKKα-NIK axis in different tumour settings. Nevertheless, few have been done in this direction, mainly because IKKα plays a role in the canonical NF-kB pathway too, and can phosphorylate IKKβ, possibly leading to the same toxicity effect of IKKβ direct inhibition [

24,

26]. Up to now, few data is available about the IKK inhibition in CTCL cell lines: IKKβ inhibition leads to a decreased cell number after 72 hours in HH, MyLa, and SeAx (p < 0.05) [

27].

3.2. TAK1 Inhibitor in CTCL

Upstream IKK, two kinases are essential for IKK activation, representing putative therapeutic targets, TAK1 and NIK. It is proposed to be preferential to inhibit NIK (NF-kB-Inducing-Kinase) instead of IKKα in the non-canonical pathway. However, very few NIK inhibitors are known in the literature [

24], and no tests have been conducted on CTCL.

TGFB-Activated Kinase 1 (TAK1) is a member of the MAP kinase kinases family involved in the NF-kB activation. Once TAK1 is activated downstream by TRAF6 and Ubc13, it phosphorylates and activates IKK [

27,

28,

29]. In CTCL cells, TAK1 is constitutively active and maintains the NF-kB activation. Up to now,

in vitro and

in vivo studies have been conducted to evaluate TAK1 inhibition in CTCL. In particular, the TAK1 inhibitor 5Z-7-Oxozeaenol has been tested in SeAx, MyLa, and HH cell lines. This study showed that TAK1 inhibition promotes apoptosis and induces 70-80% growth reduction 36 hours after treatment in HH and SeAx cells. This is associated with decreased p65-NF-kB nuclear levels and downregulation of NF-kB target genes. An

in vivo study displayed a reduction of CTCL-derived tumour growth, likely due to decreased cell proliferation and increased apoptosis, confirming the positive effects of TAK1 inhibition. Furthermore, TAK1 sustains the β-catenin signalling too [

27]. β-catenin is known to exert a pro-tumorigenic role in T-cell neoplasms and in CTCL progression [

30]; in addition, Wnt/β-catenin and NF-kB are interconnected pathways since they can reciprocally regulate each other [

31]. The same study reported before proved that the TAK1 inhibition in CTCL cell lines obtained with 5Z-7-Oxozeaenol blocked the β-catenin signalling too [

27]. Thus, TAK1 inhibition represents a crucial approach to block concomitantly both aberrant signalling. TAK1 inhibitors implementation in clinical practice has been limited because of the lack of selectivity within the human kinome and lack of oral bioavailability. However, new promising molecules were recently developed, such as HS-276 which has been demonstrated to overcome these limitations and could be exploited to acquire more knowledge about TAK1 inhibition in CTCL [

32].

4. MAPK Signalling

The mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are proteins located in the cytoplasm that contribute to the phosphorylation of many other proteins, and some can translocate to the nucleus for phosphorylating nuclear transcription factors. The MAPK family is one of the key cellular signalling pathways and is based on several cascades like ERK, p38 and PI3K/Akt, which receive external stimuli and spread through the subsequent elements from the same MAPK family. These signals can be orchestrated by regulating their amplitude and duration, and in that way, cells will deliver many responses such as proliferation, migration, differentiation, and apoptosis, among others [

33,

34].

4.1. ERK Signalling

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK), also known as MAPK3/1, is a serine/threonine protein and a core member of the MAPKs, which plays an important role in cell growth, development, and division. This cascade starts the transduction of the signal in the cytoplasm with Ras (upstream G protein), continues with Raf (downstream G protein) and MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK1/2), and ends in ERK by translocating to the nucleus to regulate transcription factors. Therefore, ERK activation will regulate gene expression depending on the different stimuli perceived from the microenvironment, such as growth factors, cytokines, G-protein-coupled receptor ligands, and oncogene signals [

33]. Furthermore, ERK1/2 has been related to cell survival, while JNK and p38 are more related to apoptosis [

35].

4.2. MAPK/ERK Inhibitors Effect on Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis in CTCL In Vitro Models

Recently, mutations affecting key players of the MAPK signalling pathway have been detected, such as gain of function mutations of ERK1 and B-Raf signalling in MF patients. Even in advanced stages of CTCL, there were Ras mutated keeping MAPK signalling activated thus the cell survival. Another factor implicated is JNK, with an increased expression in MF and SS patients that can lead to cell proliferation and differentiation [

1]. So Chakraborty et al. found that using Romidepsin (HDACi) combined with MEK inhibitors produced more apoptosis in cells expressing Ras mutated than only by romidepsin treatment [

36]. Some authors like Kießling et al. chose a more unspecific treatment like Sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor, which produces apoptosis and an anti-proliferative effect in CTCL lines, like HuT-78, SeAx, MyLa, and HH [

37]. In addition, Karagianni et al. demonstrated that Resminostat (HDACi) in combination with Ruxolitinib (JAK1/2i) exerted good results by inhibiting p-Akt and p-JNK levels and MAPK activation in both Myla and SeAx cell lines [

11].

4.3. MAPK/ERK Inhibitors Effect on CTCL Microenvironment

In the microenvironment, increased expression of miR-155 in lymphoid tissue, including MF, was observed with increasing lesion severity, and treated with Cobomarsen (miR-155 inhibitor).

In vitro, HuT-102 MF cell line was constitutively expressing MAPK/ERK signalling and Cobomarsen decreased its hyperactivation and ERK1/2 phosphorylation, thus decreasing cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis [

38].

4.4. Clinical Trials of MAPK/ERK Inhibitors in CTCL

The multikinase inhibitor Sorafenib was approved for renal and hepatocellular carcinomas and has already been tested in CTCL cells which generates the blockage of Raf by inhibiting p-MEK and p-ERK. Thus, in a study in 2014 of 12 patients with refractory/relapsed CTCL, nine had an ORR of 22%, although six patients stopped the administration of Sorafenib due to adverse effects. Nevertheless, Sorafenib demonstrated better results in combination with an HDACi, named Vorinostat, by causing apoptosis [

37].

5. p38 Signalling

p38 is a family of serine/threonine protein kinases with a molecular weight of 38 kDa and they are a class of MAPKs consisting of p38α, p38β, p38γ, and p38δ. P38 kinases are activated by MAP kinase kinases 3 and 6 (MKK3/6) [

39,

40]. They act as gene regulators by targeting transcription factors under normal or cellular stress conditions [

40]. Also, it has been found that these proteins are activated by various proinflammatory stimuli, and can induce cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, or invasion too [

41](p. 38). Moreover, it has been described that p38β can have a cytoprotective effect, or even, p38γ may have an important role in CTCL development [

39].

5.1. p38 Inhibitors Effect on Differentiation and Apoptosis in CTCL In Vitro Models

Importantly, it has to be considered that each p38 member has a specific activation motif that stimulates the canonical p38 pathway, but an alternative one exists, which is crucial for the activation and differentiation of T cells [

39]. Yong et al. treated the CTCL cell line Hut-78 with CSH71, a p38γ inhibitor, which could mediate the apoptosis of the CTCL cells [

41](p. 38). Although, a complete loss of p38γ could easily cause inflammation, autoimmune disorders, and cancer. So p38γ can be targeted for treating CTCL due to its high expression in CTCL cell lines; p38β has an increased expression too [

39]. On one hand, there have been described p38γ,δ-selective inhibitors type I like Imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine, which can be used in combination for treating CTCL. On the other hand, UM-60 which is an ATP-competitive p38α MAPK inhibitor, similar to Skepinone-L a type I inhibitor, reported the highest effect on the inhibition of STAT1α phosphorylation [

42].

5.2. Clinical Trials of p38 Inhibitors in CTCL

ATI-450, a strong p38α inhibitor, started to be used for treatment in rheumatoid arthritis with good response and now, it is already in phase II clinical trials and planned to be oriented towards other diseases, such as psoriasis or cancer, so it can be a potential treatment for CTCL [

42].

6. PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signalling

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Protein Kinase-B/mechanistic target of rapamycin (PI3K/Akt/mTOR) signalling pathway is formed of important kinases which regulate the transmission of external stimuli into the cells. They are usually activated by oncogenes and growth factor receptors to promote cell growth, differentiation, survival, cellular metabolism, and cytoskeletal reorganisation responses. This pathway is frequently altered in cancer since there are tumour suppressors linked to this signalling, and some somatic mutations appear in several solid tumours and haematological diseases, including CTCL [

43,

44].

Since the phosphorylated version of the main proteins of the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway was found in both MF and SS patients, like p-Akt, or hyperactivated p-mTOR, it is important to know if, in these pathologies, they suffer some alterations like mutations. Indeed, PI3K and PTEN were identified to be related to TCR-CD28 signalling and deletions, respectively. While phosphorylation of Akt can be used as a biomarker of poor prognosis, PTEN phosphatase can inhibit PI3K/Akt downstream signalling [

1].

Furthermore, miR-122 was highly expressed in advanced stages of MF in the malignant T cells, directly related to the activation of Akt and the inhibition of TP53. In this way, these genetic alterations are not likely to produce protein alterations in the primary tumour, so this may be caused in the CTCL microenvironment through the secretion of cytokines by malignant T cells and the activation of other pathways (JAK/STAT) [

1]. Both pathways communicate by cross talks and, as mentioned before, JAK/STAT activated signalling will keep cell proliferation and survival. In addition, the secretion of CCL21 in the microenvironment by epithelial, dendritic, and endothelial cells, along with the production of chemokines, induces mTOR hyperactivation which causes the proliferation of malignant T cells and a more aggressive phenotype in CTCL [

5].

6.1. PI3K/Akt/mTOR Inhibitors in CTCL In Vitro and In Vivo Models

Five CTCL cell lines were used, Myla, HuT-102, HuT-78, MJ, and HH, to stimulate CD4+ T-cell receptors and then treated with Cobomarsen (miR-155i) or Idelalisib, a small molecule inhibitor of PI3K/Akt signalling. It demonstrated that either Cobomarsen or Idelalisib decreased dramatically Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation [

1]. Another potential drug is ND-16 that, as mentioned before, inhibits effectively key cellular pathways and, among them, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK pathways [

18]. According to Karigianni et al., it was also analysed

in vivo models: CAM xenografted tumours in chicken models of MyLa and SeAx cells, that were treated with Ruxolitinib, significantly decreased p-Akt and p-ERK, while in combination with Resminostat (HDACi) inhibited phosphorylation of p38 too [

14].

6.2. Clinical Trials Targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signalling Pathway in CTCL

In a phase II clinical trial, Everolimus, an mTOR inhibitor, was administered to 16 relapsed T-cell lymphoma patients and it had a good response with an ORR of 44% [

45]. In a phase I study, blocking upstream the cascade in 19 CTCL patients by using Duvelisib, a dual PI3K-δ and PI3K-γ inhibitor, had an ORR of 32%, probably due to its specificity to constitutive expression of p-Akt. The most unfavourable effects of Duvelisib were neutropenia, maculopapular rash, and pneumonia, so it needs to be evaluated for better efficacy and an optimal dose consensus [

46].

Table 1.

Molecular inhibitors of key dysregulated pathways in CTCL. Some drugs have been used for in vitro or in vivo studies or are already in clinical trials for CTCL.

Table 1.

Molecular inhibitors of key dysregulated pathways in CTCL. Some drugs have been used for in vitro or in vivo studies or are already in clinical trials for CTCL.

| Signalling pathway |

Kinase target |

Drug |

Tests and results on CTCL |

JAK/STAT

|

JAK1/2 |

Ruxolitinib |

Positive results from in vitro, in vivo and clinical studies. |

| |

|

|

JAK3

JAK2

JAK1/2/3

SYK

JAK1 |

Tofacitinib

ND-16

Cerdulatinib

Upadacitinib |

Interfering with pro-tumorigenic signaling in vitro. Blocking of xenografted CTCL primary tumour formation in vivo.

Blocking of metastatic cascade in vivo: migration, invasion and extravasation inhibition of SeAx cells; reduced liver and lung metastasis from MyLa and SeAx-derived xenograft tumour. Clinical trial (phase II): ORR 11%; best response in SPTCL patients (CBR 100%). Case reports and case series: higher effectiveness in SPTCL.

In vitro study: cytotoxic effect in MyLa, SeAx, HH, HuT-78 cell lines.

In vitro study: cell cycle arrest and increased apoptosis in H9 cell line.

Clinical trial (phase II): ORR 35%, with highest ORR in MF patients.

Case reports: complete response in two MF patients. |

NF-kB

|

TAK1

|

5Z-7-Oxozeaenol

|

In vitro study: reduced proliferation and apoptosis induction in HH and SeAx cells. CTC-derived tumour growth reduction. |

IKKβ |

HS-276

BAY65-8072 |

No results on CTCL. Suggested.

In vitro study: reduced HH, MyLa, and SeAx cell growth. |

MAPK/ERK

|

ERK1/2

|

Cobomarsen

|

In vitro study: miR-155 inhibitor which decreases ERK1/2 phosphorylation in HuT-102 MF cell line. |

Multikinase

Inhibitor

|

Sorafenib

|

In vitro study: inhibits p-MEK and p-ERK successfully in HuT-78, SeAx, MyLa, and HH cell lines.

Clinical trial: ORR of 22% with multiple adverse effects.

|

JNK

|

Ruxolitinib

|

In vitro study: combination with Resminostat (HDACi) alters p-JNK levels and inhibits MAPK activation in Myla and SeAx cell lines. |

MEK

|

Selumetinib

|

In vitro study: combination with Romidepsin (HDACi) produced more apoptosis in cells expressing Ras mutated in HuT-78 cell line. |

| P38 |

p38γ |

CSH71 |

In vitro study: apoptosis in HuT-78 cell line. |

p38γ,δ

p38α |

Imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine

UM-60

ATI-450 |

No results on CTCL. Suggested.

In vitro study. Not approved drug.

No results on CTCL. Suggested. |

PI3K/Akt/mTOR

|

PI3K/Akt

p-Akt

mTOR

PI3Kγ,δ |

Idelalisib

ND-16

Ruxolitinib

Everolimus

Duvelisib |

In vitro study: combination with Cobomarsen produced depletion of both Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

In vitro study: depletion of key signalling pathways in H9 cells.

In vivo study: combination with Resminostat (HDACi) inhibited p-p38, p-Akt and p-ERK usin MyLa and SeAx cell lines in derived xenografted tumours.

Clinical trial (phase II): ORR 44% in relapsed CTCL patients.

Clinical trial (phase I): ORR 32% with several adverse effects. |

7. Conclusions

The main purpose of this review is to recapitulate the current strategies for CTCL that target key kinases of important cellular signalling pathways which are found altered in this pathology. We have focused our attention on five signalling pathways: JAK/STAT, NF-kB, MAPK/ERK, p38 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR.

JAK inhibitors have shown to be very promising kinase inhibitors for CTCL patients, even if larger clinical studies are needed to investigate their efficacy and safety. Based on the evidence that emerged from the in vitro and in vivo studies reported, their clinical evaluation in combination with HDAC inhibitors will be of particular interest. These studies also highlight TAK1 as a promising putative target to block the aberrant NF-kB signalling activation in CTCL. Thanks to the advance in TAK1 inhibitors development, it will be possible to better explore their efficacy as CTCL treatment.

JAK inhibitors also can be applied to inhibit efficiently the MAPK signalling pathway like ND-16 or Ruxolitinib in combination with HDACi. Inhibition by MAPK inhibitors decreased a lot of p-Akt and p-ERK1/2. It means that tumours with a particular protein expression profile can be treated with this kind of inhibitor, like MEK inhibitors with HDACi when Ras mutated is upregulated, Cobomarsen inhibiting constitutive expression of MAPK and miR-155 or, even, from a clinical point of view, Everolimus and Duvelisib could potentially inhibit when p-Akt was constitutively expressing. However, still, there is not a consensus on dose optimal administration, there are not high response rates in all patients, there are drugs under investigation, or presence of multiple adverse effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization S.V-D. and C.A.; writing-original draft, S.V-D. and C.A.; writing-review & editing S.V-D., C.A. and B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministerio de Innovación, Ciencia y Universidades, MICIU PID2020-(112760RB-100; BC), and LA FUNDACIÓ D’ESTUDIS I RECERCA ONCOLÒGICA (FERO) grant (BFERO2021.03). SV-D is a predoctoral fellow funding by Fundación Científica de la Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (FC AECC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- N. Rendón-Serna, L. A. Correa-Londoño, M. M. Velásquez-Lopera, and M. Bermudez-Muñoz, ‘Cell signaling in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma microenvironment: promising targets for molecular-specific treatment’, Int. J. Dermatol., vol. 60, no. 12, pp. 1462–1480, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Vahabi et al., ‘JAK Inhibitors in Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma: Friend or Foe? A Systematic Review of the Published Literature’, Cancers, vol. 16, no. 5, p. 861, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Dummer et al., ‘Cutaneous T cell lymphoma’, Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 61, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Hague, N. Farquharson, L. Menasce, E. Parry, and R. Cowan, ‘Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: diagnosing subtypes and the challenges’, Br. J. Hosp. Med., vol. 83, no. 4, pp. 1–7, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Pavlidis, C. Piperi, and E. Papadavid, ‘Novel therapeutic approaches for cutaneous T cell lymphomas’, Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol., vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 629–641, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- de Masson et al., ‘Allogeneic transplantation in advanced cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CUTALLO): a propensity score matched controlled prospective study’, The Lancet, vol. 401, no. 10392, pp. 1941–1950, 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Hu, J. Li, M. Fu, X. Zhao, and W. Wang, ‘The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: from bench to clinic’, Signal Transduct. Target. Ther., vol. 6, no. 1, p. 402, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Groner and V. von Manstein, ‘Jak Stat signaling and cancer: Opportunities, benefits and side effects of targeted inhibition’, Mol. Cell. Endocrinol., vol. 451, pp. 1–14, 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. P. D. Liau et al., ‘The molecular basis of JAK/STAT inhibition by SOCS1’, Nat. Commun., vol. 9, no. 1, p. 1558, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Patil et al., ‘Molecular pathogenesis of Cutaneous T cell Lymphoma: Role of chemokines, cytokines, and dysregulated signaling pathways’, Semin. Cancer Biol., vol. 86, pp. 382–399, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Karagianni et al., ‘Ruxolitinib with resminostat exert synergistic antitumor effects in Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma’, PLOS ONE, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 1–14, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Shawky, F. A. Almalki, A. N. Abdalla, A. H. Abdelazeem, and A. M. Gouda, ‘A Comprehensive Overview of Globally Approved JAK Inhibitors’, Pharmaceutics, vol. 14, no. 5, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Y. McGirt et al., ‘Whole-genome sequencing reveals oncogenic mutations in mycosis fungoides’, Blood, vol. 126, no. 4, pp. 508–519, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Karagianni et al., ‘Combination of Resminostat with Ruxolitinib Exerts Antitumor Effects in the Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane Model for Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma’, Cancers, vol. 14, no. 4, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Yumeen et al., ‘JAK inhibition synergistically potentiates BCL2, BET, HDAC, and proteasome inhibition in advanced CTCL’, Blood Adv., vol. 4, no. 10, pp. 2213–2226, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pérez et al., ‘Mutated JAK kinases and deregulated STAT activity are potential therapeutic targets in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma’, Haematologica, vol. 100, no. 11, pp. e450–e453, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Karagianni et al., ‘010 - In vitro effect of Jak and HDAC inhibitors in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma’, Abstr. EORTC-CLTF 2019 Meet. Cutan. Lymphoma Insights Res. Patient Care, vol. 119, p. S4, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhu et al., ‘ND-16: A Novel Compound for Inhibiting the Growth of Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma by Targeting JAK2’, Curr. Cancer Drug Targets, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 328–339, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Dai and M. Duvic, ‘Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma: Current and Emerging Therapies’, 2023.

- K. Vadivel et al., ‘Staphylococcus aureus induces drug resistance in cancer T cells in Sézary syndrome’, Blood, vol. 143, no. 15, pp. 1496–1512, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T.-P. Chang and I. Vancurova, ‘NFκB function and regulation in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma’.

- Y. Li et al., ‘Inhibition of NF-κB signaling unveils novel strategies to overcome drug resistance in cancers’, Drug Resist. Updat., vol. 73, p. 101042, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Xia et al., ‘Role of the NFκB-signaling pathway in cancer’, OncoTargets Ther., vol. Volume 11, pp. 2063–2073, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Paul, J. Edwards, C. Pepper, and S. Mackay, ‘Inhibitory-κB Kinase (IKK) α and Nuclear Factor-κB (NFκB)-Inducing Kinase (NIK) as Anti-Cancer Drug Targets’, Cells, vol. 7, no. 10, 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. L. Zinzani et al., ‘Phase II Trial of Proteasome Inhibitor Bortezomib in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma’, J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 25, no. 27, pp. 4293–4297, Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Prescott and S. J. Cook, ‘Targeting IKKβ in Cancer: Challenges and Opportunities for the Therapeutic Utilisation of IKKβ Inhibitors’, Cells, vol. 7, no. 9, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Gallardo et al., ‘Novel phosphorylated TAK1 species with functional impact on NF-κB and β-catenin signaling in human Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma’, Leukemia, vol. 32, no. 10, pp. 2211–2223, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Wuerzberger-Davis and S. Miyamoto, ‘TAK-ling IKK Activation: “Ub” the Judge’, Sci. Signal., vol. 3, no. 105, pp. pe3–pe3, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Takaesu, R. M. Surabhi, K.-J. Park, J. Ninomiya-Tsuji, K. Matsumoto, and R. B. Gaynor, ‘TAK1 is Critical for IκB Kinase-mediated Activation of the NF-κB Pathway’, J. Mol. Biol., vol. 326, no. 1, pp. 105–115, Feb. 2003. [CrossRef]

- B. Bellei, C. Cota, A. Amantea, L. Muscardin, and M. Picardo, ‘Association of p53 Arg72Pro polymorphism and β-catenin accumulation in mycosis fungoides’, Br. J. Dermatol., vol. 155, no. 6, pp. 1223–1229, Dec. 2006. [CrossRef]

- B. Ma and M. O. Hottiger, ‘Crosstalk between Wnt/β-Catenin and NF-κB Signaling Pathway during Inflammation’, Front. Immunol., vol. 7, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Scarneo, P. Hughes, R. Freeze, K. Yang, J. Totzke, and T. Haystead, ‘Development and Efficacy of an Orally Bioavailable Selective TAK1 Inhibitor for the Treatment of Inflammatory Arthritis’, ACS Chem. Biol., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 536–544, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Guo, W. Pan, S. Liu, Z. Shen, Y. Xu, and L. Hu, ‘ERK/MAPK signalling pathway and tumorigenesis (Review)’, Exp. Ther. Med., Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Brown and D. B. Sacks, ‘Compartmentalised MAPK Pathways’, in Protein-Protein Interactions as New Drug Targets, E. Klussmann and J. Scott, Eds., Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2008, pp. 205–235. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xia, M. Dickens, J. Raingeaud, R. J. Davis, and M. E. Greenberg, ‘Opposing Effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP Kinases on Apoptosis’, Science, vol. 270, no. 5240, pp. 1326–1331, Nov. 1995. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Chakraborty et al., ‘MAPK pathway activation leads to Bim loss and histone deacetylase inhibitor resistance: rationale to combine romidepsin with an MEK inhibitor’, Blood, vol. 121, no. 20, pp. 4115–4125, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Kießling et al., ‘NRAS mutations in cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) sensitize tumors towards treatment with the multikinase inhibitor Sorafenib’, Oncotarget, vol. 8, no. 28, pp. 45687–45697, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Seto et al., ‘Cobomarsen, an oligonucleotide inhibitor of miR-155, co-ordinately regulates multiple survival pathways to reduce cellular proliferation and survival in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma’, Br. J. Haematol., vol. 183, no. 3, pp. 428–444, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. H. Zhang et al., ‘Targeting the non-ATP-binding pocket of the MAP kinase p38γ mediates a novel mechanism of cytotoxicity in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL)’, FEBS Lett., vol. 595, no. 20, pp. 2570–2592, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Chang and M. Karin, ‘Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades’, Nature, vol. 410, no. 6824, pp. 37–40, Mar. 2001. [CrossRef]

- H.-Y. Yong, M.-S. Koh, and A. Moon, ‘The p38 MAPK inhibitors for the treatment of inflammatory diseases and cancer’, Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs, vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 1893–1905, Dec. 2009. [CrossRef]

- V. Haller, P. Nahidino, M. Forster, and S. A. Laufer, ‘An updated patent review of p38 MAP kinase inhibitors (2014-2019)’, Expert Opin. Ther. Pat., vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 453–466, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Altomare and J. R. Testa, ‘Perturbations of the AKT signaling pathway in human cancer’, Oncogene, vol. 24, no. 50, pp. 7455–7464, Nov. 2005. [CrossRef]

- S. Noorolyai, N. Shajari, E. Baghbani, S. Sadreddini, and B. Baradaran, ‘The relation between PI3K/AKT signalling pathway and cancer’, Gene, vol. 698, pp. 120–128, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. E. Witzig et al., ‘The mTORC1 inhibitor everolimus has antitumor activity in vitro and produces tumor responses in patients with relapsed T-cell lymphoma’, Blood, vol. 126, no. 3, pp. 328–335, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Horwitz et al., ‘Activity of the PI3K-δ,γ inhibitor duvelisib in a phase 1 trial and preclinical models of T-cell lymphoma’, Blood, vol. 131, no. 8, pp. 888–898, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).