Submitted:

29 May 2024

Posted:

03 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

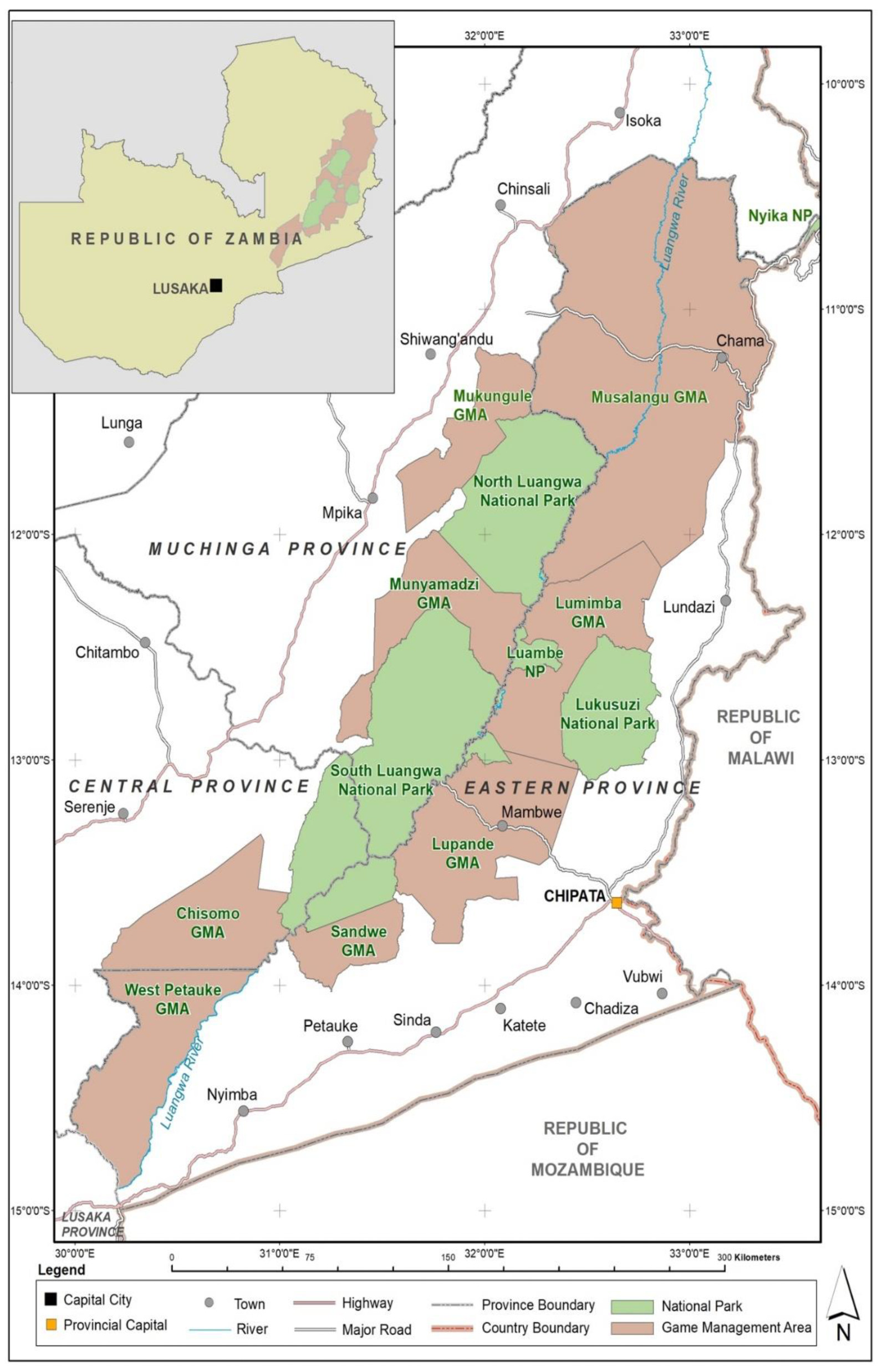

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Survey Design

2.3. Quantitative Approach

2.3.1. Study Population and Sample Size

2.3.2. Data Collection Methods and Tools

2.4. Qualitative Approach

2.4.1. Focus Group Discussions

2.4.2. In-Depth Interviews

2.5. Validity and Reliability of Study Instruments

2.6. Data Analyses

2.6.1. Response Frequencies on Drivers of Illegal Hunting and Intervention Measures

2.6.2. Relationships between Drivers of Illegal Hunting and Intervention Measures

2.6.3. Comparing Responses in Sampling Strata

2.6.4. Hypotheses Testing

2.6.5. Predicting the Likelihood of High Persistence of Illegal Hunting

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Validity, Reliability and Trustworthiness of Study Instruments and Process

3.2. Quantitative Approach

3.2.1. Demographics and Socio-Economic Characteristics of Respondents

3.2.2. Illegal Hunting Drivers, Levels, Trends, and Persistence

3.2.3. Relationship between Illegal Hunting Drivers and Intervention Measures

3.2.4. Comparisons of Responses in Strata on Prevalent Drivers of Illegal Hunting

3.2.5. Hypotheses Testing

3.2.6. Likelihood of High Persistent Illegal Hunting in the Luangwa Valley

3.3. Qualitative Approach

3.3.1. Drivers of Illegal Hunting in the Luangwa Valley

“For instance, you will find that the elephant has killed someone, and then you hear that there is no compensation”. …. “So due to frustration, they will go and kill the animal”. …” they will kill the animal, and just leave it because of frustration”,participant #7, Kakumbi CRB FGD.

3.3.2. Limitations of Law Enforcement in Addressing Illegal Hunting

“Another thing sir is that poaching cannot end here even though there are wildlife law enforcement staff. The reason is that there is so much poverty”,Reformed Illegal Hunter #4, Mwape FGD.

“So, no matter how many law enforcement scouts there will be, but if the poacher has got no other means, and there is no other way of getting him out of poaching, then poaching will not end to say the truth.” … ”They go for poaching due to having nothing to do. So, when they find what to do, they will stop poaching”,Reformed Illegal Hunter #3, Nyalugwe FGD.

“And you know I think another factor is that when you fight them (illegal hunters), as the law enforcement tends to do, they get smarter. They don’t stop, they just get smarter. They know how to hide, they know where to move around, they figure out where to go hunting so they minimize their risk or how to, you know do things in a cleverer way. So, I don’t think fighting them necessarily can reduce poaching, but the problem is when you are unable to sustain your law enforcement, those people will be there waiting and then they will come back with a greater vengeance, with a greater aptitude for poaching”.

“… wildlife law enforcement is important, I just don’t think it is efficient…” and “… law enforcement is necessary but it’s not sufficient”,expert participant #1, IDI.

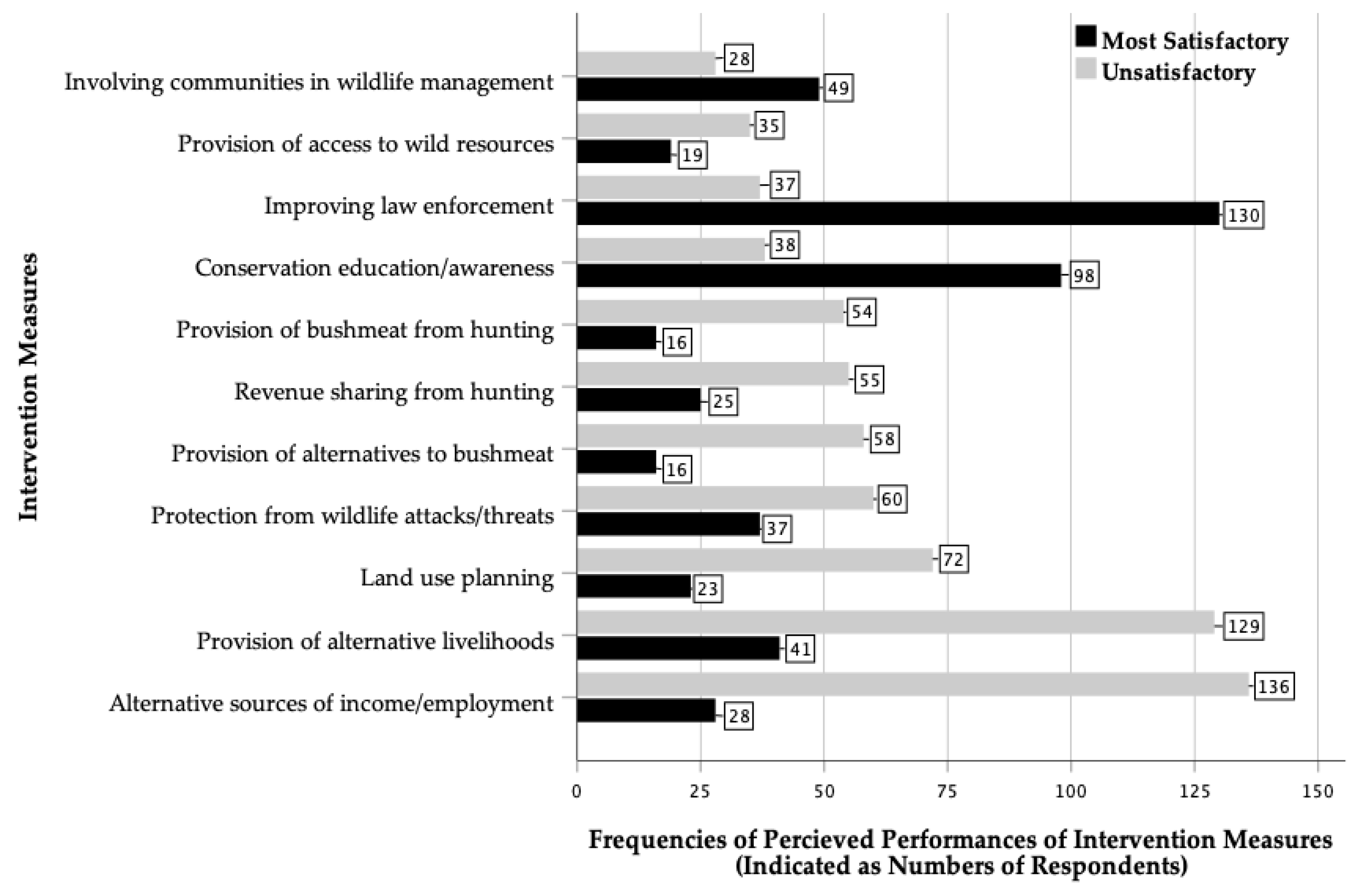

3.3.3. Unsatisfactory Performance of Intervention Measures

3.3.4. Beliefs and Behavioural Intentions to Hunt Illegally

“Let’s talk about the creation, where you asked us that why did God give us wildlife. Then there were answers that God gave wildlife to man so that he can help himself. So, if I have food, then my neighbour, not just my neighbour even my grandparents have no food not even tea, they cannot even manage to go and work on the farm. Then because of the animals that God has given us, I get up and go and kill one Common duiker and sell for (or barter with) three tins (of grain). I get one tin (of grain) and give them so that they are saved from hunger that means I have saved their lives from dying from hunger”,Reformed Illegal Hunter #5, Nyalugwe FGD.

“When the game guard is in a certain area, one just waits for two days as the game guard will move out”. … ”That is when you come out and poach from the area he has moved from”. ... “Sometimes you get information from people that game guards are in this area, so you go the other way to poach animals”,Reformed Illegal Hunter #2, Luembe FGD.

“To stop poaching is difficult”. … “Yes, for you to stop poaching you have to find what to do in place of poaching”. … “Starting to poach is easier than stopping. One time a friend of mine poached and gave me some bushmeat and I didn’t have a firearm. The bushmeat was good so I also looked for a firearm and started poaching”,Reformed Illegal Hunter #8, Mwape FGD.

“What causes poaching are the problems that we face in our homes. That is why we go poaching. We kill animals to get help in our homes”,Reformed Illegal Hunter #1, Jumbe FGD.

“… God gave wildlife to man so that he can help himself. … Then because of the animals that God has given us, I get up and go and kill one Common duiker and sell for (or barter with) three tins (of grain). I get one tin (of grain) and give them so that they are saved from hunger that means I have saved their lives from dying from hunger”,Reformed Illegal Hunter #5, Nyalugwe FGD.

4. Discussion

4.1. Reliability, Validity and Trustworthiness of Study Instruments and Process

4.2. Drivers, Intervention Measures and Persistence of Illegal Hunting

4.3. Defiance/Protesting Unfairness

4.4. Beliefs and Behavioural Intentions to hunt Illegally

4.5. Limitations of Law Enforcement in Addressing Illegal Hunting

4.6. Different Perspectives on Drivers of Illegal Hunting and Intervention Measures

4.7. Proposed Postulation on Persistence of Illegal Hunting

4.8. Limitations of the Study

4.9. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brodie, J.F. & Gibbs, H.K. 2009. Bushmeat hunting as climate threat. Science, 326:364-365.

- Ceballos, G., Ehrlich, P.R., Barnosky, A.D., García, A., Pringle, R.M. & Palmer, T.M. 2015. Accelerated modern human-induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Science Advances. 1: e1400253.

- Ripple, W.J., Abernethy, K., Betts, M.G., Chapron, G., Dirzo, R., Galetti, M., Levi, T., Lindsey, P.A., MacDonald, D.W., Machovina, B., Newsome, T.M., Peres, C.A., Wallach, A.D., Wolf, C. & Young, H. 2016. Bushmeat hunting and extinction risk to the world’s mammals. Royal Society Open Science, 3:160498. [CrossRef]

- Halabowski, D. & Ryzmski, P. 2020. Taking a lesson from COVID-19 pandemic: Preventing the future outbreaks of viral zoonoses through multi-faceted approach. Science of the Total Environment, 757 (2021) 143723. [CrossRef]

- Bennet, E.L. & Robinson, J.G. 2023. To avoid carbon degradation in tropical forests, conserve wildlife. PLoS Biol 21(8): e3002262. [CrossRef]

- Kahler, S.J., Roloff, G. & Gore, L.G. 2013. Poaching risks in a Community-Based Natural Resource System. Journal of Conservation Biology, 27:177-186.

- von Essen, E., Hansen, H.P., Källström, H.N., Peterson, M.N. & Peterson T.R. 2014. Deconstructing the poaching phenomenon. British Journal of Criminology, 54:632-651.

- Duffy, R., St. John, F.A.V., Büscher, B. & Brockington, D. 2016. Towards a new understanding of the links between poverty and illegal hunting. Conservation Biology,. [CrossRef]

- Moreto, W.D. & Lemieux, A.M. 2015. Poaching in Uganda: Perspectives of Law enforcement Rangers. Deviant Behaviour, 36:853-873. [CrossRef]

- Challender, D.W.S. and MacMillan, D.C. 2014. Poaching is more than an enforcement problem. Conservation Letters, 7:484-494.

- Cooney, R., Roe, D., Dublin, H., Phelps, J., Wilkie, D., Keane, A., Travers, H., Skinner, D., Challender, D.W.S., Allan, J.R. & Biggs, D. 2017. From poachers to protectors: Engaging local communities in solutions to illegal wildlife trade. Conservation Letters 10(3), 367-374.

- Holden, M.H., Biggs, D., Brink, H., Bal, P., Rhodes, J. & McDonald-madden, E. 2019. Increasing anti-poaching law enforcement or reducing demand for wildlife products? A framework to guide strategic conservation investments. Conservation Letters. [CrossRef]

- Zyambo, P., Kalaba, FK., Nyirenda, VR. & Mwitwa, J. 2022. Conceptualising drivers of illegal hunting by local hunters living in or adjacent African protected areas: A scoping review. Sustainability, 14(18): 11204. [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.H., Lopez-Bao, J.V., Bruskotter, J.T., Gore, M., Chapron, G., Johnson, A., Epstein, Y., Shrestha, M., Frank, J., Ohrens, O. & Treves, A. 2017. A conceptual framework for understanding illegal killing of large carnivores. Ambio, 46:251-264.

- Lindsey, P.A., Balme, G., Becker, M., Begg, C., Bento, C., Bocchino, C., Dickman, A., Diggle, R.W., Eves, H., Henschel, P., Lewis, D., Marnewick, K., Mattheus, J., McNutt, J.W., McRobb, R., Midlane, N., Milanzi, J., Morley, R., Murphree, M., Opyene, V., Phadima, J., Purchase, G., Rentsch, D., Roche, C., Shaw, J., van der Westhuizen, H., Van Vliet, N., & Zisadza-Gandiwa, P. 2013. The bushmeat trade in African savannas: Impacts, drivers and possible solutions. Biological Conservation, 160:80-96.

- Alvard, M. 1993. Testing the ‘Ecologically Noble Savage’ Hypothesis: interspecific prey choice by Piro hunters of Amazon Peru. Human Ecology, 21:355-387.

- Alvard, M. 1995. Intraspecific prey choice by Amazonian hunters. Current Anthropology, 36:789-818.

- Stephens, D.W. & Krebs, J.R. 1987. Foraging Theory. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

- Scott, J. 2000. Rational choice theory. In: Garry Browning, Abigail Halcli and Frank Webster (eds), Understanding Contemporary Society: Theories of the Present. London, UK, Sage Publications Ltd. pp 126-138.

- Wortley, R. 2017. Situational precipitator of crime. In: R. Mortley and M. Townsley (Eds.), Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis. 2nd ed., pp. 62-86. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Moreto, W.D. 2019. Provoked poachers? Applying a situational precipitator framework to examine the nexus between human-wildlife conflict, retaliatory killings, poaching. Criminal Justice Studies. [CrossRef]

- Sherman, L.W. 1993. Defiance, deterrence, and irrelevance: A theory of criminal sanction. Journal of research in Crime and Delinquency, 30 (4): 445-473.

- Witter, R. 2021. Why militarized conservation may be counter-productive: illegal wildlife hunting as defiance. Journal of Political Ecology, 28(1):175-192.

- Ajzen, I. 1985. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behaviour. In J. Juhi & J. Beckmann (Eds), Action-Control: From Cognition to Behaviour, pp 11-39, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

- Ajzen, T. 1991. The theory of planned behaviour. Organisational Behaviour and Human Decision Process, 50(2):179-211.

- Ajzen, T. 2012. The Theory of Planned Behaviour. In P.A.M. Lange, A.W. Kruglanski & E.T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology Vol. 1, pp 438-459. London, UK: Sage.

- Gibson, C.C. & Marks, S.A. 1995. Transforming rural hunters into conservationists: An assessment of Community Based Wildlife Management Program in Africa. World Development, 23:941-957.

- Lewis, D.M. & Phiri, A. 1998. Wildlife snaring – an indicator of community response to a community-based conservation project. Oryx, 32:111-121.

- Marks, S. 2001. Back to the future: Some unintended consequences of Zambia’s Community-Based Wildlife Program (ADMADE). Africa Today, 48:120-141.

- Becker, M.S., McRobb, R., Watson, F., Droge, E., Kanyembo, B. & Kakumbi, C. 2013. Evaluating wire-snare poaching trends and impacts of by-catch on elephants and large carnivores. Biological Conservation, 158:26-36.

- Nyirenda, V., Lindsey, P.A., Phiri, E., Stevenson, I., Chomba, C., Namukonde, N., Myburgh, W.J. & Reilly, B.K. 2015. Trends in illegal killing of elephants (Loxodonta Africana) in the Luangwa and Zambezi ecosystems of Zambia. Environment and Natural Resources Research, 5:24-36.

- Leader-Williams, N., Albon, S.D. & Berry, P.S.M. 1990. Illegal exploitation of black rhinoceros and elephant populations: patterns of decline, law enforcement and patrol effort in the Luangwa Valley, Zambia. Journal of Applied Ecology, 27:1055-1087.

- Jackmann, H. & Billiouw, M. 1997. Elephant poaching and law enforcement in the central Luangwa Valley, Zambia. Journal of Applied Ecology, 33:1241-1250.

- Chomba, C. and Matandiko, W. 2011. Population status of black and white rhinos in Zambia. Pachyderm, 50:50-55.

- Chomba, C., Simukonda, C., Nyirenda, V. & Chisangano, F. 2012. Population status of the African elephant in Zambia. Journal of Ecology and Natural Environment, 4(7): 186-193.

- White, P.A. and Van Valkenburgh, B. 2022. Low-cost forensics reveal high rates of non-lethal snaring and shotgun injuries in Zambia’s large carnivores. Front. Conserv. Sci. 3:803381. [CrossRef]

- Watson, F., Becker, M.S., McRobb, R. & Kanyembo, B. 2013. Spatial patterns of wires-snare poaching: implications for community conservation in the buffer zones around National Parks. Biological Conservation 168:1-9.

- Milner-Gulland, E.J. & Leader-Williams, N. 1992. A model of incentives for illegal exploitation of black rhinos and elephants – poaching pays in Luangwa-Valley, Zambia. Journal of Applied Ecology, 29:388-401.

- Brown, T. & Marks, S.A. 2007. Livelihood, hunting and the game meat trade in Northern Zambia. In: Glyn Davies and David Brown (eds), Bushmeat and Livelihoods: Wildlife Management and Poverty Reduction. Oxford, UK, Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp 92-105.

- King, E.C.P. 2014. Hunting for a problem: An investigation into bushmeat use around North Luangwa National Park, Zambia. MSc Thesis, Imperial College London. pp 85.

- Astle, W.L., Webster, R. & Lawrence, C.J. 1969. Land classification for management planning in Luangwa Valley, Zambia. Journal of Applied Ecology, 6:143-169.

- Astle, W.L. 1989. Republic of Zambia, South Luangwa National Park Map: Landscape and Vegetation. Lowell Johns Ltd, Oxford.

- Caughley, G. & Goddard, J. 1975. Abundance and distribution of elephants in the Luangwa Valley, Zambia. East African Wildlife Journal, 13:39-48.

- Kothari, C.R. 2004. Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques. 2nd Revised Edition, New Age International Publishers, New Delhi. pp 401.

- Matthews, B. & Ross, L. 2010. Research Methods – A practical guide for the social sciences. Pearson Education Limited, Harlow, England. pp 490.

- Zambia Statistics Agency, Ministry of Health (MOH) Zambia & ICF. 2019. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2018, Lusaka, Zambia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA. pp 581.

- Yamane, T. 1967. Statistics: An Introductory Analysis. 2nd Ed. New York, Harper and Row.

- Adam, A.M. 2020. Sample size determination in survey research. Journal of Scientific Research and Reports, 26:90-97.

- Muth, R.M. & Bowe, J.F. 1998. Illegal harvest of renewable natural resources in north America: Toward a typology of the motivations for poaching. Society & Natural Resources, 11(1): 9-24.

- Nyumba, T.O., Wilson, K., Derrick, C.J. & Mukherjee, N. 2018. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9:20-32.

- Cresswell, J.W. 2009. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. 3rd Edition, SAGE, Los Angeles. pp 260.

- Heale, R. & Twycross, A. 2015. Validity and reliability in quantitative research. Evidence Based Nursing, 18:66-67.

- Lincoln, Y.S. & Guba, E.G. 1986. But Is It Rigorous? Trustworthiness and Authenticity in Naturalistic Evaluation. In: D.D. Williams (Ed), Naturalistic Evaluation: New Directions for Program Evaluation, no. 30. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass. pp 73 – 84.

- Lincoln, Y.S. & Guba, E.G. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Newburry Park, California: Sage.

- Guba, E.G. & Lincoln, Y.S. 1994. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. Denzu and Y. Lincoln (eds). Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, California, Sage, pp 105 – 117.

- Cope, D.G. 2014. Methods and Meanings: Credibility and Trustworthiness of Qualitative Research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41:89-91.

- Nowell, L.S., Norris, J.M., White, D.E. & Moules, N.J. 2017. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16:1-13.

- Geist, H.J. & Lambin, E.F. 2002. Proximate causes and underlying driving forces of tropical deforestation. BioScience, 52:143-150.

- Jellason, N.P., Robinson, E.J.Z., Chapman, A.S.A., Neina, D., Devenish, A.J.M., Po, J.Y.T. & Adolph, B. 2021. A systematic review of drivers and constraints on agricultural expansion in sub-Saharan Africa. Land, 10:332. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H. 2021. Introduction and overview. In: Hugh L. Wagner (ed), The psychobiology of human motivation. Classic Edition, Abingdon, Oxon, UK, Routledge. pp 1-21.

- Bennett, E.L., Blencowe, E., Brandon, K., Brown, D., Burn, R.W., Cowlishaw, G.U.Y., Davies, G., Dublin, H., Fa, J.E., Milner-Gulland, E.J., Robinson, J.G., Rowcliffe, J.M., Underwood, F.M. & Wilkie, D.S. 2007. Hunting for consensus: Reconciling bushmeat harvest, conservation and development policy in West and Central Africa. Conservation Biology 21(3), 884-887.

- Alexander, J.S., McNamara, J., Rowcliffe, M.J., Oppong, J., & Milner-Gulland, E.J. 2015. The role of bushmeat in a West African agricultural landscape. Oryx 49(4), 643-651.

- Hariohay, K.M., Ranke, P.S., Fyumagwa, R.D., Kideghesho, J.R. & Røskaft, E. 2019. Drivers of conservation crime in Rungwa-Kizigo-Muhesi Game Reserves, Central Tanzania. Global Ecology and Conservation 17, e00522. [CrossRef]

- Lubilo, R. & Hebinck, P. 2019. ‘Local hunting’ and community-based natural resources management in Namibia: contestations and livelihood. Geoforum, 101:62-75.

- Armitage, C.J. & Conner, M. 2001. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 471-499.

- Steinmetz, H., Knappstein, M., Ajzen, I., Schmidt, P. & Kabst, R. 2016. How effective are behavior change interventions based on the theory of planned behavior? Zeitschrift für Psychologie,. [CrossRef]

- Newth, J.L., McDonald, R.A., Wood, K.A., Rees, E.C., Semenov, I., Christyakov, A., Mikhaylova, G., Bearhop, S., Cromie, R.L., Belousova, A., Glazov, P. & Nuno, A. 2021. Predicting intention to hunt protected wildlife: a case study of Bewick’s swan in the European Russian Artic. Oryx 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Kisingo, A., Wilfred, P., Magige, F., Kayeye, H., Nahonyo, C. & Milner-Gulland, E. 2022. Resource managers’ and users’ perspectives on factors contributing to unauthorised hunting in western Tanzania. African Journal of Ecology, 00:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. 2015. Association, correlation and causation. Nature Methods, 12, 899-900.

|

Sampling Strata |

Illegal Hunting Status in the Luangwa Valley | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levels | Persistence | Trends | ||||||||

| Low | Moderate | High | < 1 year (Starting) |

1-14 years (Short) |

15-30 years (Long) |

>30 years Very long |

Decreased | Stable | Increased | |

| Reformed Illegal Hunters | 93 | 42 | 7 | 0 | 108 | 30 | 4 | 93 | 27 | 21 |

| Community Resource Boards |

40 | 20 | 3 | 1 | 32 | 11 | 18 | 49 | 13 | 1 |

| Wildlife Agency Staff | 9 | 55 | 30 | 5 | 33 | 26 | 30 | 48 | 29 | 17 |

| Conservation Interested Entities |

13 | 22 | 10 | 0 | 11 | 12 | 22 | 20 | 16 | 9 |

| Total | 155 (45.1%) | 139 (40.4%) | 50 (14.5%) | 6 (1.7%) |

184 (53.6%) | 79 (23.0%) | 74 (21.6%) | 210 (61.2%) |

85 (24.8%) | 48 (14.0%) |

| *Drivers of illegal hunting | No. of respondents identifying drivers (% in parentheses) |

Proximate/ underlying drivers |

Thematic drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of alternative sources of income/employment | 197 (56.9%) | Proximate | Need for survival & sustaining livelihoods |

| Poverty | 195 (56.4%) | Underlying | Need for survival & sustaining livelihoods |

| Need for bushmeat consumption |

183 (52.9%) | Proximate | Need for survival & sustaining livelihoods |

| Need for income from bushmeat & animal products |

180 (52.0%) | Proximate | Need for survival & sustaining livelihoods |

| Sponsorship to hunt illegally | 132 (38.2%) | Underlying | External/internal sponsorship |

| Lack of sources of meat/ protein |

112 (32.4%) | Proximate | Need for survival & sustaining livelihoods |

| Retaliatory killing | 96 (27.7%) | Proximate | Human-wildlife conflicts |

| Preventative killing | 84 (24.3%) | Proximate | Human-wildlife conflicts |

| Human-wildlife conflicts | 79 (22.9%) | Underlying | Human-wildlife conflicts |

| Demand for wildlife products | 70 (20.2%) | Underlying | Market demand for wildlife products |

| Lack/inadequate conservation education/awareness | 70 (20.2%) | Underlying | Lack of conservation education/awareness |

| Lack/inadequate tangible benefits from conservation |

52 (15.0%) | Underlying | Need for survival & sustaining livelihoods |

| Population influx/increase | 49 (14.2%) | Underlying | Demographic growth |

| Inadequate community involvement in wildlife management |

47 (13.6%) | Underlying | Inadequate devolution of wildlife management |

| Weak/inadequate law enforcement |

39 (11.3%) | Underlying | Inadequate legislation/ enforcement |

| Need for trophies for income/use |

34 (9.8%) | Proximate | Need for survival & sustaining livelihoods |

| Cultural/traditional needs | 20 (5.9%) | Proximate | Cultural needs/ significance |

| Political influence | 15 (4.3%) | Underlying | Political influence |

| Defiance/protest | 10 (2.9%) | Proximate | Defiance/protesting unfairness |

| Recreational/sports needs | 5 (1.4%) | Proximate | Recreational need |

| Desire to outsmart law enforcement staff |

5 (1.4%) | Proximate | Desire to outsmart law enforcement staff |

| Intervention Measures | No. of Respondents Identifying Intervention Measures |

Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Improving law enforcement |

213 | 61.6 |

| Providing conservation education/awareness |

207 | 59.8 |

| Provision of alternative livelihoods |

187 | 54.0 |

| Provision of alternative sources of income/ employment |

152 | 43.9 |

| Involving communities in wildlife management | 112 | 32.4 |

| Protecting communities from animal attacks & threats | 99 | 28.6 |

| Revenue sharing from hunting | 80 | 23.1 |

| Land use planning | 62 | 17.9 |

| Provision of bushmeat from hunting | 49 | 14.2 |

| Provision of alternative to bushmeat | 27 | 7.8 |

| Provision of access to wild resources |

26 | 7.5 |

| Driver of Illegal Hunting | *Likelihood Ratio | Degrees of freedom (df) | Cramer’s V | P-value | Decision | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Need for bushmeat consumption | 23.209 | 3 | 0.243 (p < 0.001) |

< 0.001 | Reject null hypothesis | Evidence for a moderate association |

| Need for income from bushmeat | 8.019 | 3 | 0.152 (p = 0.047) |

= 0.046 | Reject null hypothesis | Evidence for a weak association |

| Preventative killing | 16.626 | 3 | 0.200 (p = 0.003) |

< 0.001 | Reject null hypothesis | Evidence for a moderate association |

| Human-wildlife conflicts | 20.129 | 3 | 0.243 (p < 0.001) |

< 0.001 | Reject null hypothesis | Evidence for a moderate association |

| Need for trophies for income/use | 13.745 | 3 | 0.206 (p = 0.002) |

= 0.003 | Reject null hypothesis | Evidence for a moderate association |

| Lack of tangible benefits from conservation |

14.296 | 3 | 0.202 (p < 0.001) |

= 0.003 | Reject null hypothesis | Evidence for a moderate association |

| Poverty | 2.651 | 3 | 0.087 (p = 0.451) | = 0.449 | Retain null hypothesis | No evidence for association |

| Lack of alternative income/ employment |

3.358 | 3 | 0.098 (p = 0.347) |

= 0.340 | Retain null hypothesis | No evidence for association |

| Lack of alternative source of meat | 3.374 | 3 | 0.096 (p = 0.360) |

= 0.338 | Retain null hypothesis | No evidence for association |

| Retaliatory killing | 5.154 | 3 | 0.161 (p = 0.169) |

= 0.169 | Retain null hypothesis | No evidence for association |

| Intervention Measures with Unsatisfactory Performance |

*Likelihood Ratio | Degrees of Freedom (df) | Cramer’s V | P-value | Decision | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provision of alternative livelihoods | 13.367 | 3 | 0.253 (p = 0.004) |

= 0.004 | Reject null hypothesis | Evidence for a moderate association |

| Provision of alternatives to bushmeat |

32.488 | 3 | 0.366 (p < 0.001) |

< 0.001 | Reject null hypothesis | Evidence for a strong association |

| Provision of bushmeat from hunting | 19.029 | 3 | 0.276 (p < 0.001) |

< 0.001 | Reject null hypothesis | Evidence for a moderate association |

| Revenue sharing from hunting | 34.533 | 3 | 0.372 (p < 0.001) |

< 0.001 | Reject null hypothesis | Evidence for a strong association |

| Provision of access to wild resources | 11.980 | 3 | 0.305 (p = 0.01) |

= 0.007 | Reject null hypothesis | Evidence for a strong association |

| Provision of alternative employment/ income |

5.476 | 3 | 0.156 (p = 0.136) | = 0.140 | Retain null hypothesis | No evidence for association |

| Protection of communities from attacks and threats of wild animals | 0.122 | 3 | 0.024 (p = 0.989) |

= 0.989 | Retain null hypothesis | No evidence for association |

| Model 1: Predictors include drivers of illegal hunting. Method: Forward Stepwise (Likelihood Ratio) | ||||||||

| Omnibus Test of Model Coefficient: χ2 = 37.404, df = 4, P < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 = 0.357 = 35.7% | ||||||||

| Hosmer & Lemeshow Test: χ2 = 1.101, df = 6, P = 0.981 | ||||||||

| Percentage Accuracy in Classification (PAC) = 71.3% | ||||||||

| 95% CI for Exp(B) | ||||||||

| B | SE | Wald | df | Sig | Exp(B) | Lower | Upper | |

| Poaching level (low) Ref | 13.870 | 2 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Poaching level (moderate) | 1.272 | 0.460 | 7.650 | 1 | 0.006 | 3.568 | 1.449 | 8.787 |

| Poaching level (high) | 2.727 | 0.869 | 9.840 | 1 | 0.002 | 15.293 | 2.782 | 84.057 |

| No alternative meat | 1.061 | 0.500 | 4.507 | 1 | 0.034 | 2.890 | 1.085 | 7.696 |

| Need income from bushmeat | 1.296 | 0.443 | 8.577 | 1 | 0.003 | 3.660 | 1.536 | 8.723 |

| Constant | -2.591 | 0.564 | 21.665 | 1 | < 0.001 | 0.075 | ||

| Model 2: Predictors include intervention measures. Method: Forward Stepwise (Likelihood Ratio) | ||||||||

| Omnibus Test of Model Coefficient: χ2 = 23.640, df = 3, P < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 = 0.222 = 22.2% | ||||||||

| Hosmer & Lemeshow Test: χ2 = 0.384, df = 3, P = 0.944 | ||||||||

| Percentage Accuracy in Classification (PAC) = 73.7% | ||||||||

| 95% CI for Exp(B) | ||||||||

| B | SE | Wald | df | Sig | Exp(B) | Lower | Upper | |

| Poaching level (low) Ref | 12.723 | 2 | 0.002 | |||||

| Poaching level (high) | 2.928 | 0.839 | 12.179 | 1 | < 0.001 | 18.689 | 3.609 | 96.771 |

| Most satisfactory performance: conservation education/awareness |

-1.073 | 0.413 | 6.754 | 1 | 0.009 | 0.342 | 0.152 | 0.768 |

| Constant | -0.687 | 0.299 | 5.291 | 1 | 0.021 | 0.503 | ||

| Model 3: Combined significant predictors from models 1 and 2. Method: Enter | ||||||||

| Omnibus Test of Model Coefficient: χ2 = 30.389, df = 5, P < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 = 0.191 = 19.1% | ||||||||

| Hosmer & Lemeshow Test: χ2 = 4.229, df = 8, P = 0.836 | ||||||||

| Percentage Accuracy in Classification (PAC) = 71.7% | ||||||||

| 95% CI for Exp(B) | ||||||||

| B | SE | Wald | df | Sig | Exp(B) | Lower | Upper | |

| Poaching level (low) Ref | 14.229 | 2 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Poaching level (moderate) | 0.843 | 0.341 | 6.115 | 1 | 0.013 | 2.323 | 1.191 | 4.532 |

| Poaching level (high) | 1.871 | 0.550 | 11.587 | 1 | < 0.001 | 6.494 | 2.212 | 19.070 |

| Most satisfactory performance: conservation education/awareness |

-0.690 | 0.323 | 4.563 | 1 | 0.033 | 0.502 | 0.266 | 0.945 |

| No alternative meat | 0.738 | 0.348 | 4.491 | 1 | 0.034 | 2.091 | 1.057 | 4.138 |

| Constant | -1.459 | 0.382 | 14.583 | 1 | < 0.001 | 0.232 | ||

| Theme: Drivers of Illegal Hunting | |||||||||||||||||

| Protesting unfairness / injustices | Poverty | Inadequate law enforcement | Need for income |

Human wildlife conflicts |

Lack of alternative livelihood |

Limited tangible benefits | Lack of employment |

Inadequate community involvement | Demand/market for bushmeat or products |

Lack of alternative meat/food |

Limited access to bushmeat | Poor partnerships/ collaboration | Encroachment & development |

Inadequate awareness / sensitisation | Human pop/ influx increase |

Communities don’t own wildlife |

|

| FGDs | 19 (5) | 14 (6) | 11 (1) | 10 (4) | 10 (3) | 8 (3) | 7 (3) | 6 (3) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IDIs | 0 | 2 (1) | 12 (3) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (1) | 0 | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Theme: Intervention Measures | |||||||||||||||||

| Provision of alternative livelihoods | Improve benefits from wildlife |

Provision of employment | Sensitisation awareness |

Improving law enforcement |

Involving Communities in conservation |

Stakeholders collaboration |

Human Wildlife Conflict mitigation |

Provision of bushmeat or alternatives |

Improving conservation funding |

||||||||

| FGDs | 21 (6) | 12 (6) | 9 (5) | 5 (4) | 5 (2) | 4 (4) | 4 (3) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | |||||||

| IDIs | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | |||||||

| Theme: Unsatisfactory Intervention Performance | |||||||||||||||||

| Provision of alternative livelihoods | Provision of employment | Improving law enforcement | HW conflict mitigation | Bushmeat/ alternative meat provision |

Provision/ access to tangible benefits |

Conservation sensitisation/ awareness | Community involvement conservation |

||||||||||

| FGDs | 14 (5) | 12 (4) | 12 (3) | 7 (3) | 5 (3) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |||||||||

| IDIs | 1 (1) | 0 | 8 (3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (2) | |||||||||

| Theme: Behavioural Beliefs (attitude) | |||||||||||||||||

| Wildlife was given for use | Poaching is good for survival | Wildlife was given as food | Poaching is bad | God’s gift for livelihood & survival | Wildlife is God’s creation | Poaching, the only means for survival | Hunting is traditional | Wildlife brings wealth | |||||||||

| FGDs | 9 (4) | 5 (4) | 4 (3) | 3 (3) | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||||||||

| Theme: Normative Beliefs | |||||||||||||||||

| Poaching helps people to survive | Some may not support poaching | People support poaching |

|||||||||||||||

| FGDs | 5 (3) | 4 (2) | 4 (1) | ||||||||||||||

| Theme: Control Beliefs | |||||||||||||||||

| Easy to start poaching | Difficult to stop poaching |

Easy to stop poaching | |||||||||||||||

| FGDs | 12 (5) | 6 (3) | 3 (2) | ||||||||||||||

| Theme: Types of Illegal Hunters | |||||||||||||||||

| Local illegal hunters | Non-local | ||||||||||||||||

| FGDs | 20 (7) | 2 (2) | |||||||||||||||

| IDIs | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | |||||||||||||||

| Theme: Limitations of Law Enforcement | |||||||||||||||||

| FGDs | 18 (6) | ||||||||||||||||

| IDIs | 6 (3) | ||||||||||||||||

| Theme: Behavioural Intentions to Hunt Illegally | |||||||||||||||||

| FGDs | 17 (6) | ||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).