1. Introduction

Student-athletes must balance numerous and often competing demands that increase their risk for symptoms of mental illness [

1]. Yet, there is mixed evidence in the literature, mainly drawn from North American samples, as to whether student-athletes are at less, as much, or at more risk for experiencing symptoms of mental illness than their non-athlete counterparts [

2]. To broaden our understanding and better support UK student-athletes’ mental health, there is a need to explore prevalence rates within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic as there is a gap for comparing rates of mental illness symptoms before and after the pandemic. Uncovering rates of mental illness post-pandemic is vital for informing sufficient mental health support is provided to meet the needs of student-athletes.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a global issue that presented challenges for physical and mental health [

3,

4]. A national lockdown was announced on 23rd March 2020 in the UK whereby normal sporting activities were suspended as well as campus-based learning, presenting challenges for student-athletes alongside existing pressures [

1]. Worldwide, symptoms of depression and anxiety rose by 25% during this period across all ages [

5]. Mental health problems were also evidenced in multiple populations such as Italian students [

6], those with pre-existing mental health disorders [

7], and Australian general population [

8]. For students, it was widely assumed that university closures and ambiguity in exam procedures would impact their mental health [

9]. It is unclear however, whether student-athletes followed this trend given that young people were disproportionately affected by the pandemic [

5,

10]. It is, therefore, necessary for those working with athletes, including universities, to understand the impact of the pandemic on student-athlete mental health to ensure appropriate support is provided. Findings from this study will not only be beneficial for supporting student-athletes now but for potential future increased rates of COVID-19 lockdowns or periods of isolation (e.g., injury, outbreaks of other diseases).

The national lockdown resulted in the suspension of normal sporting activities, as well as campus-based learning, presenting new and unfamiliar challenges for student-athletes alongside existing pressures of their dual career identity [

1]. Exasperating the situation further, student-athletes also experienced a loss of typical protective factors associated with their sport, such as training, social interaction, and learning, which was shown to contribute to anxiety about the future [

11]. Despite an overall increase in symptom severity pre- to post-pandemic in North American samples [

12], research suggests that athletes with greater protective factors may have been less severely impacted by the pandemic. For example, physical activity was found to be a protective factor for young people’s mental health and well-being during the pandemic [

13]. Previous findings from North America also found that student-athletes’ with higher levels of social support and connectedness during the pandemic reported fewer problems with their mental health [

14], and that student-athletes had somewhat better coping mechanisms than student-nonathletes [

12]. Given that the policies for COVID-19 restrictions differed across countries, there is a need to understand UK student-athletes’ mental illness over COVID-19.

It is rare that an opportunity arises to investigate what happens when key features of university and sport are removed, with the last instance of this situation relating to the suspension of all sports during World War II in the 1940’s [

15]. This knowledge could help to inform the provision of sports and mental health support in the future by exploring the historical macro-time component of the Process, Person, Context, Time (PPCT) model [

16,

17] to provide valuable insight into the effects this can have on student-athletes’ symptoms of mental illness. This endeavor would provide novel insight and extend current knowledge on how the ecological systems in which athletes exist influences their experience of symptoms of mental illness.

Therefore, through a multiple cohort cross-sectional design, the aim of this study is to investigate UK student-athletes’ symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic. It was hypothesized that there would be higher symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress in the post-pandemic cohort compared to the pre-pandemic cohort.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Following ethical approval, data were collected from 807 student-athletes representing different sport types (team = 462, individual = 342, 3 did not specify) and competitive levels (recreational = 158, club = 257, regional = 328, elite = 58, 6 did not specify), aged 18-25 (M = 19.98 years, SD = 1.50) enrolled at UK universities. The sample consisted of 305 student-athletes who identified as male, 501 who identified as female, and 1 who did not specify.

2.2. Procedures and Data Collection

Data was obtained from two separate cohorts as part of larger studies using a multiple cohort cross-sectional study design. The pre-pandemic cohort completed questionnaires between November 2018 and March 2020 (n = 427). The post-pandemic cohort completed questionnaires between November 2021 and November 2022 (n = 380), shortly after restrictions were lifted in the UK for the last time.

2.2. Measures

Participants completed the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) [

18], a 21-item measure with 7 items each for depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms, reported on a Likert-type scale from 0

‘did not apply to me at all’ to 3

‘applied to me very much or most of the time’. Cronbach alpha coefficients in the present study were good (stress = .84, anxiety = .80, depression = .89) demonstrating reliable internal consistency. Total scores were created for each sub-scale and multiplied by 2 [

18]. The DASS-21 has been validated for use in athlete populations during and post-COVID-19 [

19].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Using SPSS v.29, data was cleaned and screened for missing data and outliers [

20]. Depression, anxiety, and stress were continuous variables and used to conduct a repeated measures multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) test for comparing mean scores. These continuous variables were also transformed into categorical variables to understand the distribution of student-athletes across symptom severity from normal, mild, moderate, severe to extremely severe symptoms [

18]. Cross-tabulations and chi-squared tests were conducted on the categorical variables to assess for statistically significant differences in symptom severity pre- to post-pandemic.

3. Results

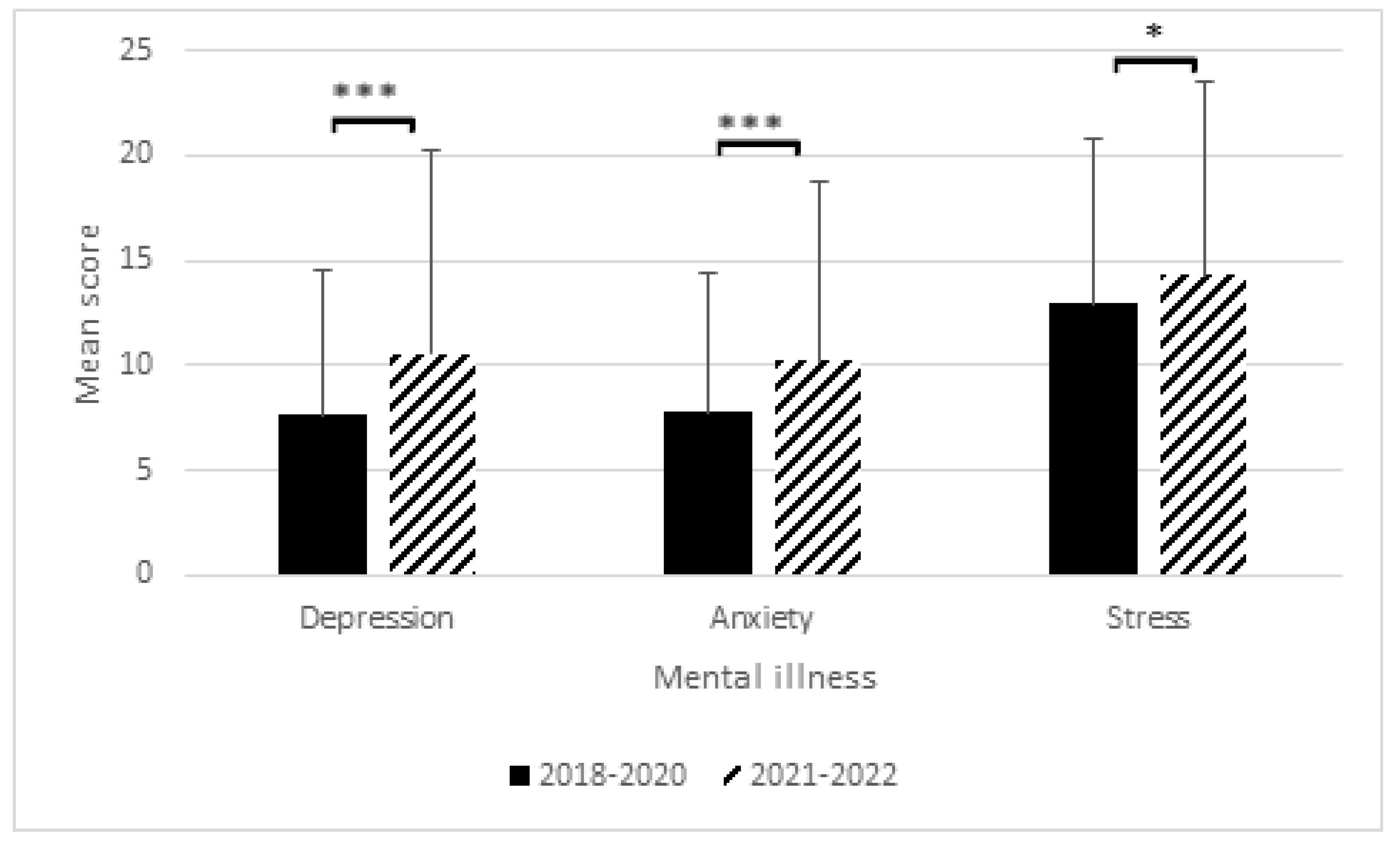

Results of the MANOVA revealed student-athletes post-pandemic reported higher levels of mental illness compared to the pre-pandemic cohort (Pillai’s trace = .040,

F (3, 803) = 11.28,

p <.001,

Ƞ2p = .040, observed power = 99.9%). At the univariate level, these differences were statistically significant for depressive (

F (1, 805) = 23.92,

p <.001,

Ƞ2p = .029, observed power = 99.8%), anxiety (

F (1, 806) = 20.15,

p <.001,

Ƞ2p = .024, observed power = 99.4%), and stress symptoms (

F (1, 805) = 5.24,

p = .022,

Ƞ2p = .006, observed power = 62.8%) (

Figure 1). That is, student-athletes’ reported higher rates of depression, anxiety, and stress in the post-pandemic cohort.

Crosstabulations and chi-squared tests revealed statistically significant differences in the distribution of student-athletes across symptom severity (

Table 1) for depression (X

2 = 29.28, df = 4,

p <.001) and anxiety (X

2 = 27.86, df = 4,

p <.001) from pre- to post-pandemic. There were no statistically significant differences in distribution for stress (X

2 = 9.45, df = 4,

p =.051). Results highlight that student-athletes in the post-pandemic cohort reported proportionately greater symptoms of depression and anxiety compared to those at pre-pandemic.

4. Discussion

Despite previous research, predominantly from North American samples, indicating mixed results on the extent to which student-athletes are at risk for mental illness [

2], from the current results it is clear that UK student-athletes are experiencing difficulties with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress pre- but especially post-pandemic and there is an urgent need to support their mental health. Research has shown the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of North American student-athletes [

12,

14], and of UK 13-19 year olds [

13]. Although the authors argue that athletes appeared to face fewer mental health challenges when compared to non-athletes, they did note that post-pandemic scores for anxiety were nonetheless higher than pre-pandemic values [

12]. The present findings follow this trend of heightened post-pandemic symptoms and enhance our understanding on student-athlete mental health by providing novel knowledge on UK student-athletes symptoms of mental illness as a population who experience different health, educational, and sporting contexts to those in North America [

2]. The findings are also situated within the time component of the PPCT model [

16,

17] and provide valuable insight into the effects this can have on student-athletes’ symptoms of mental illness. Although COVID-19 was a major global stressor, on a smaller scale, student-athletes may experience other periods of isolation that mimic some of the features of the pandemic, such as the removal of sport protective factors.

4.1. Symptoms Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Pandemic

Symptoms of depression and anxiety were elevated over the COVID-19 pandemic and thus, is one of the many factors that has worsened mental health. In particular, depressive symptoms heightened from normal to mild levels, anxiety from normal to mild, and stress from normal to borderline mild. A key clinical implication of the present findings is that these symptoms will get worse without intervention, that students will leave university with poor mental health that could have been supported, or drop out of university altogether [

21]. To identify potential intervention targets, future research should explore protective factors for student-athletes for any future eventualities of pandemics or other stressors which relate to periods of isolation from sport (e.g., injury).

4.2. Symptom Severity

For depressive and anxiety symptoms, the severity has significantly skewed towards more severe categories of symptoms from pre- to post-pandemic. 46.6% of student-athletes reported mild to extremely severe symptoms of depression post-pandemic compared to 32.8% pre-pandemic. 52.6% reported mild to extremely severe symptoms of anxiety post-pandemic compared to 44.3% pre-pandemic. Alarmingly, rates of extremely severe symptoms of anxiety increased from 8% to 19.5%. Importantly, the mean score (

M = 10.21) reflects mild levels of symptoms. If this alone was considered, then the large proportion experiencing extremely severe symptoms would have been missed. Further, just 7.1% are in the mild category. Anxiety appears to be a particular concern with 52.6% symptomatic with mild to extremely severe symptoms. This distinction is also important because the intervention for someone with mild symptoms might be different to those experiencing more severe symptoms (i.e., campus counselling vs. clinical treatments [

22,

23]. Although severity of symptoms of stress are not statistically significantly different post-pandemic, the mean score has significantly increased, and so student-athletes also require support managing their symptoms of stress.

4.3. Strengths & Limitations

A strength of this study is its contribution to knowledge on UK student-athlete mental illness, but particularly when faced with challenges presented by factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic. A key limitation of the present study is in the cross-sectional design. That is, different cohorts participated at the two time points. Nevertheless, the heterogeneity of the sample provides opportunity to generalise the findings to student-athletes broadly. Future research should explore ways in which student-athlete mental health can be promoted, such as by exploring their symptoms of well-being and various risk and protective factors that are associated with their symptoms of mental illness.

4.4. Conclusion

Taken together, the results indicate that large proportions of student-athletes reported heightened symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress pre-pandemic, suggesting they were struggling with their mental health. However, post-pandemic, the severity of symptoms heightened for some student-athletes experiences of depression and anxiety. This clear increase in rates of student-athletes’ symptoms of mental illness warrants immediate attention to understand how best to support their mental health, considering the broader ecological system. Future research should aim to address this problem to understand how athletes, coaches, universities, and others who work with them can be aware of their symptoms of mental illness and support these athletes but also to investigate whether interventions can be implemented to reduce the risk of such symptoms in the first instance during this peak developmental period. The findings highlight that severe implications can occur when key features of the sport environment are removed. Therefore, key, unique features of the sport environment should be researched to understand how they influence student-athletes mental health (mental illness and well-being).

Author Contributions

All authors (G.B., M.Q., and J.C.) contributed to the design, data collection, drafting, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript. All authors (G.B., M.Q., and J.C.) read and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Funding

This research was funded by the lead authors studentship, Economic and Social Research Council, grant number ES/P000711/1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Prior to commencement of the study, ethical approval was obtained from the University of Birmingham (UK) ethics committee (ERN_18-1430 and SPP2122_05). ERN_18-1430 was approved on 14 January 2019 and SPP2122_05 on 4 November 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the first author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all student-athletes who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Moreland, J. J., Coxe, K. A., & Yang, J. (2018). Collegiate athletes’ mental health services utilization: A systematic review of conceptualizations, operationalizations, facilitators, and barriers. In Journal of Sport and Health Science (Vol. 7, Issue 1, pp. 58–69). Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Kegelaers, J., Wylleman, P., Defruyt, S., Praet, L., Stambulova, N., Torregrossa, M., Kenttä, G., & De Brandt, K. (2022). The mental health of student-athletes: a systematic scoping review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Galea, S., Merchant, R. M., & Lurie, N. (2020). The Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19 and Physical Distancing. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(6), 817. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C., Wykes, T., Galderisi, S., Nordentoft, M., Crossley, N., Jones, N., Cannon, M., Correll, C. U., Byrne, L., Carr, S., Chen, E. Y. H., Gorwood, P., Johnson, S., Kärkkäinen, H., Krystal, J. H., Lee, J., Lieberman, J., López-Jaramillo, C., Männikkö, M., … Arango, C. (2020). How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(9), 813–824. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide [Accessed 13 November 2023].

- Meda, N., Pardini, S., Slongo, I., Bodini, L., Zordan, M. A., Rigobello, P., Visioli, F., & Novara, C. (2021). Students’ mental health problems before, during, and after COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 134, 69–77. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L., Markey, K., O’ Donnell, C., Moloney, M., & Doody, O. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and its related restrictions on people with pre-existent mental health conditions: A scoping review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 35(4), 375–394. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J., Tran, T., Hammarberg, K., Nguyen, H., Stocker, R., Rowe, H., Sastri, J., Popplestone, S., & Kirkman, M. (2021). Quantifying the mental health burden of the most severe covid-19 restrictions: A natural experiment. Journal of Affective Disorders, 293, 406–414. [CrossRef]

- Hotopf, M., Bullmore, E., O’Connor, R. C., & Holmes, E. A. (2020). The scope of mental health research during the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 217(4), 540–542. [CrossRef]

- Weber, S. R., Winkelmann, Z. K., Monsma, E. V., Arent, S. M., & Torres-McGehee, T. M. (2023). An Examination of Depression, Anxiety, and Self-Esteem in Collegiate Student-Athletes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1211. Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Title of the chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 154–196. [CrossRef]

- National Collegiate Athletic Association. NCAA student-athlete COVID-19 well-being survey, 2020. Available: https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/research/other/2020/2020RES_NCAASACOVID-19SurveyPPT.pdf [Accessed 13 November 2023].

- Strauser, C., Chavez, V., Lindsay, K., Figgins, M., & DeShaw, K. (2023). College student athlete versus nonathlete mental and social health factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of American College Health, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Wright, L. J., Williams, S. E., & Veldhuijzen van Zanten, J. (2021). Physical Activity Protects Against the Negative Impact of Coronavirus Fear on Adolescent Mental Health and Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychol, 12, 580511. [CrossRef]

- Graupensperger, S., Benson, A. J., Kilmer, J. R., & Evans, M. B. (2020). Social (un) distancing: Teammate interactions, athletic identity, and mental health of student-athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(5), 662-670. [CrossRef]

- Chandler, A. J., Arent, M. A., Cintineo, H. P., Torres-McGehee, T. M., Winkelmann, Z. K., & Arent, S. M. (2021). The Impacts of COVID-19 on Collegiate Student-Athlete Training, Health, and Well-Being. Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine, 6(4). [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. sage.

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation of Australia.

- Vaughan, R. S., Edwards, E. J., & MacIntyre, T. E. (2020). Mental Health Measurement in a Post Covid-19 World: Psychometric Properties and Invariance of the DASS-21 in Athletes and Non-athletes. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Sorkkila, M., Aunola, K., & Ryba, T. V. (2017). A person-oriented approach to sport and school burnout in adolescent student-athletes: The role of individual and parental expectations. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 28, 58–67. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, P., Arundell, L.-L., Saunders, R., Matthews, H., & Pilling, S. (2021). The efficacy of psychological interventions for the prevention and treatment of mental health disorders in university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 280, 381–406. [CrossRef]

- Mowbray, C. T., Megivern, D., Mandiberg, J. M., Strauss, S., Stein, C. H., Collins, K., Kopels, S., Curlin, C., & Lett, R. (2006). Campus mental health services: Recommendations for change. In American Journal of Orthopsychiatry (Vol. 76, Issue 2, pp. 226–237). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).