Submitted:

03 June 2024

Posted:

04 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

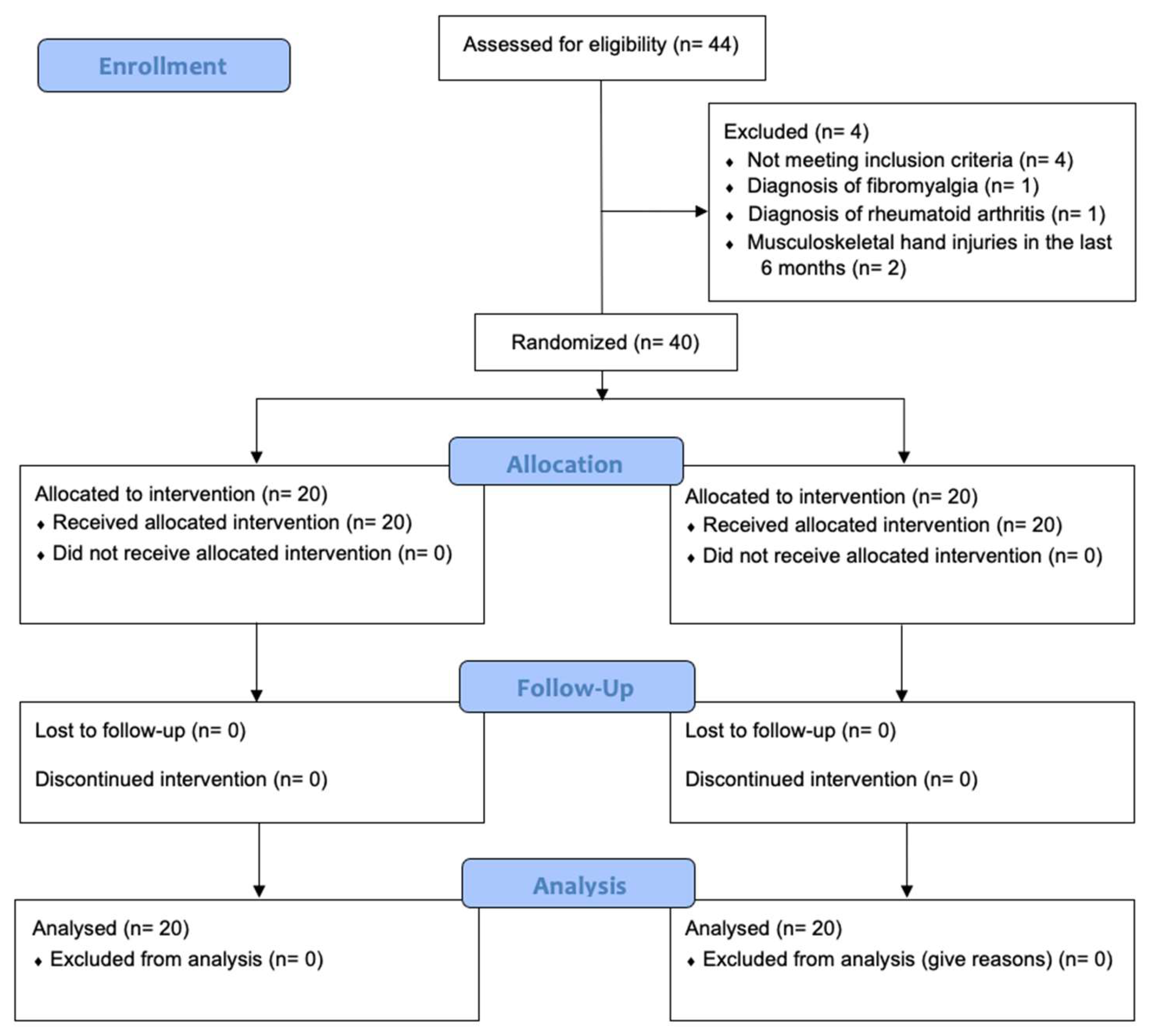

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Interventions

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Sample Size

2.6. Randomization and Blinding

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Exploratory Efficacy

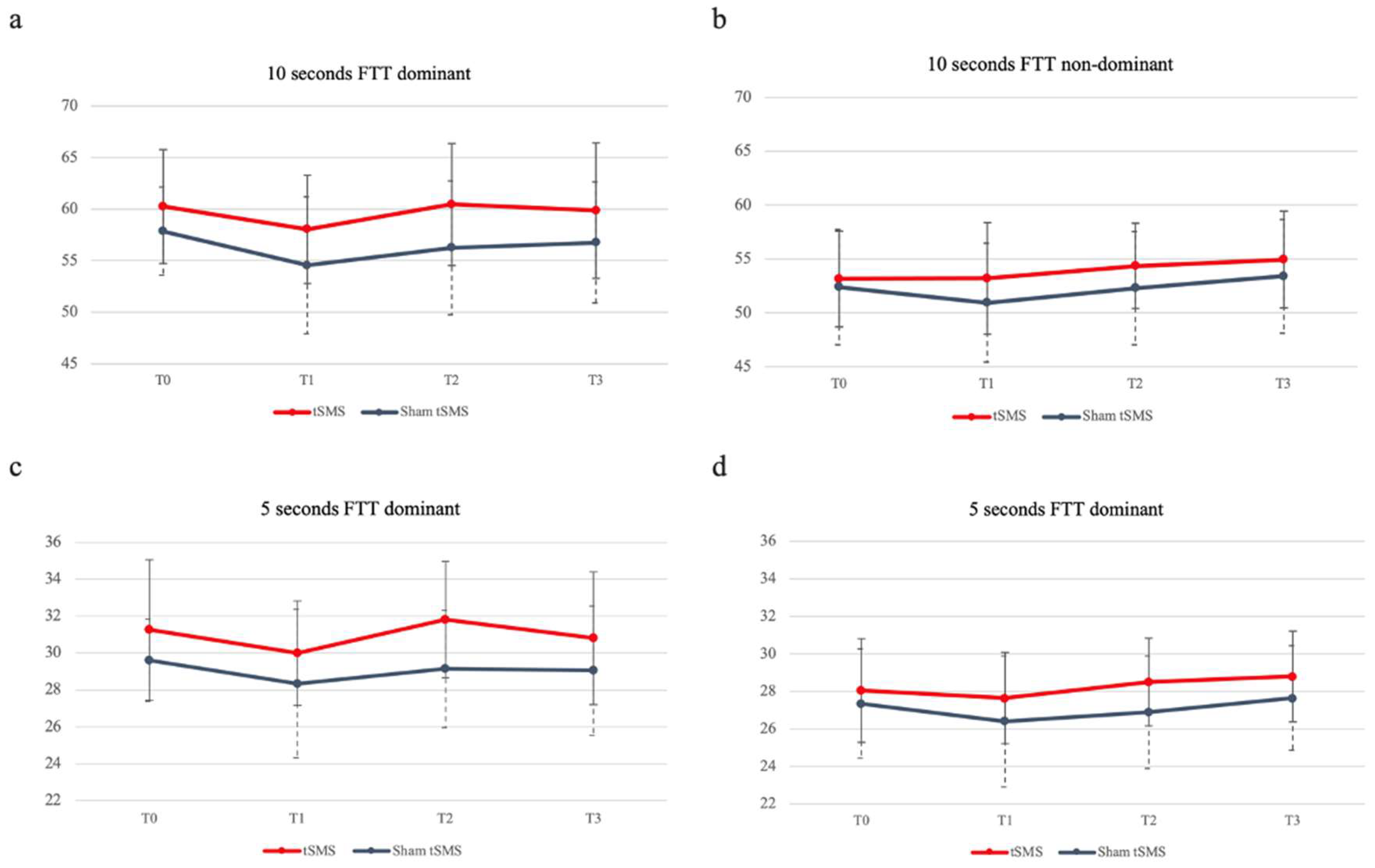

3.2.1. Finger Tapping Test

3.2.2. Nine Hole Peg Test

3.2.3. Hand Grip Strength

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oliviero, A.; Mordillo-Mateos, L.; Arias, P.; Panyavin, I.; Foffani, G.; Aguilar, J. Transcranial static magnetic field stimulation of the human motor cortex. J. Physiol. 2011, 589, 4949–4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dileone, M.; Mordillo-Mateos, L.; Oliviero, A.; Foffani, G. Long-lasting effects of transcranial static magnetic field stimulation on motor cortex excitability. Brain Stimul. 2018, 11, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nojima, I.; Oliviero, A.; Mima, T. Transcranial static magnetic stimulation —From bench to bedside and beyond—. Neurosci. Res. 2019, 156, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Sasaki, A.; Nakazawa, K. Accuracy in Pinch Force Control Can Be Altered by Static Magnetic Field Stimulation Over the Primary Motor Cortex. Neuromodulation: Technol. Neural Interface 2019, 22, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda-Pardo, J.A.; Obeso, I.; Guida, P.; Dileone, M.; Strange, B.A.; Obeso, J.A.; Oliviero, A.; Foffani, G. Static magnetic field stimulation of the supplementary motor area modulates resting-state activity and motor behavior. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemps, H.; Gervois, P.; Brône, B.; Lemmens, R.; Bronckaers, A. Non-invasive brain stimulation as therapeutic approach for ischemic stroke: Insights into the (sub)cellular mechanisms. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 235, 108160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddington, L.; Reynolds, J. Targeting interhemispheric inhibition with neuromodulation to enhance stroke rehabilitation. Brain Stimul. 2017, 10, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisicaro, F.; Lanza, G.; Grasso, A.A.; Pennisi, G.; Bella, R.; Paulus, W.; Pennisi, M. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in stroke rehabilitation: review of the current evidence and pitfalls. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2019, 12, 175628641987831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, S.; Watanabe, T.; Yukawa, Y.; Minakuchi, M.; Shimomura, R.; Mima, T. Effect of transcranial static magnetic stimulation on intracortical excitability in the contralateral primary motor cortex. Neurosci. Lett. 2020, 723, 134871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, Y.; Koganemaru, S.; Watanabe, T.; Shibata, S.; Yukawa, Y.; Minakuchi, M.; Shimomura, R.; Mima, T. Transcranial static magnetic stimulation over the motor cortex can facilitate the contralateral cortical excitability in human. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Branscheidt, M.; Schambra, H.; Steiner, L.; Widmer, M.; Diedrichsen, J.; Goldsmith, J.; Lindquist, M.; Kitago, T.; Luft, A.R.; et al. Rethinking interhemispheric imbalance as a target for stroke neurorehabilitation. Ann. Neurol. 2019, 85, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, D.A.; Grefkes, C.; Ameli, M.; Fink, G.R. Interhemispheric Competition After Stroke: Brain Stimulation to Enhance Recovery of Function of the Affected Hand. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2009, 23, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelrod, B.N.; Meyers, J.E.; Davis, J.J. Finger Tapping Test Performance as a Measure of Performance Validity. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2014, 28, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, N.-G.; Kim, G.-W.; Won, Y.H.; Park, S.-H.; Seo, J.-H.; Ko, M.-H. Timing-Dependent Effects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Hand Motor Function in Healthy Individuals: A Randomized Controlled Study. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorin, S.; Wakeford, C.; Zhang, G.; Sukamtoh, E.; Matteliano, C.J.; Finch, A.E. Beneficial effects of an investigational wristband containing Synsepalum dulcificum (miracle fruit) seed oil on the performance of hand and finger motor skills in healthy subjects: A randomized controlled preliminary study. Phytotherapy Res. 2018, 32, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grice, K.O.; Vogel, K.A.; Le, V.; Mitchell, A.; Muniz, S.; Vollmer, M.A. Adult Norms for a Commercially Available Nine Hole Peg Test for Finger Dexterity. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2003, 57, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, S.S.; Mohamad, M.; Syazarina, S.O.; Nafisah, W.Y. Hand grips strength effect on motor function in human brain using fMRI: A pilot study. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2014, 546, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, M.; Matheson, N.A.; Brownjohn, P.W.; Tang, A.D.; Rodger, J.; Shemmell, J.B.H.; Reynolds, J.N.J. Differences in Motor Evoked Potentials Induced in Rats by Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation under Two Separate Anesthetics: Implications for Plasticity Studies. Front. Neural Circuits 2016, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bestmann, S.; Krakauer, J.W. The uses and interpretations of the motor-evoked potential for understanding behaviour. Exp. Brain Res. 2015, 233, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, B.J.; Mather, M.; Livesey, E.J.; Harris, I.M.; Harris, J.A. Motor-evoked potentials reveal functional differences between dominant and non-dominant motor cortices during response preparation. Cortex 2018, 103, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froc, D.J.; Chapman, C.A.; Trepel, C.; Racine, R.J. Long-Term Depression and Depotentiation in the Sensorimotor Cortex of the Freely Moving Rat. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collingridge, G.L.; Isaac, J.T.R.; Wang, Y.T. Receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, S.F.; Bliss, T.V.P. Plasticity in the human central nervous system. Brain 2006, 129, 1659–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, A.; Proulx-Bégin, L.; Hamel, R.; De Beaumont, L.; Bernier, P.-M.; Lepage, J.-F. Static magnetic stimulation of the primary motor cortex impairs online but not offline motor sequence learning. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nojima, I.; Watanabe, T.; Gyoda, T.; Sugata, H.; Ikeda, T.; Mima, T. Transcranial static magnetic stimulation over the primary motor cortex alters sequential implicit motor learning. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 696, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimomura, R.; Shibata, S.; Koganemaru, S.; Minakuchi, M.; Ichimura, S.; Mima, T. Transcranial static magnetic field stimulation (tSMS) can induce functional recovery in patients with subacute stroke. Brain Stimul. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1- All tests were conducted in a quiet, enclosed room to reduce the effects of visual and auditory interference. |

| 2- The subjects were tested in the same room, with the same conditions, the same chair, and the same table. |

| 3- The subjects were instructed to perform the test in the same specific posture for each test. |

| 4 - The tests were performed in the same order and with the same time interval. |

| 5 - Subjects were not allowed to wear jewelry, watches, or other accessories on the upper extremities. |

| 6 - All subjects were assigned and evaluated by the same investigator. |

| 7 - All subjects were instructed by the same evaluator. The evaluator provided the same verbal instructions in the same tone of voice during each test to reduce training effects. |

| 8 - All subjects were allowed to perform a pretest, except for the finger tapping test. |

| 9 - Subjects were required to complete each individual test without rest. |

| Variable | tSMS (n = 20) | Sham tSMS (n = 20) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 27,1 ± 7,85 | 25,05 ± 8,18 | .424 |

| Gender, n male (%) | 6 (30%) | 10 (50%) | .206 |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 167,65 ± 7,55 | 168,9 ± 10,25 | .663 |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 64,82 ± 7,15 | 65,76 ± 12,98 | .776 |

| Hand of dominance, n right (%) | 19 (95%) | 20 (100%) | .33 |

| 10s FTT dominant hand (taps in 10 seconds), mean (SD) | 60,25 ± 5,54 | 57,85 ± 4,27 | .133 |

| 10s FTT non dominant hand (taps in 10 seconds), mean (SD) | 53,15 ± 4,45 | 52.40 ± 5,34 | .632 |

| 5s FTT dominant hand (taps in first 5 seconds), mean (SD) | 31,25 ± 3,08 | 29,6 ± 2,21 | .059 |

| 5s FTT non dominant hand (taps in first 5 seconds), mean (SD) | 28,05 ± 2,76 | 27,35 ± 2,91 | .44 |

| Nine Hole Peg Test dominant hand | 17,51 ± 1,85 | 17,74 ± 1,74 | .691 |

| Nine Hole Peg Test non dominant hand | 18,84 ± 2,12 | 19,6 ± 2,11 | .26 |

| Hand Grip Strength dominant hand | 33,93 ± 8,67 | 32,73 ± 11,04 | .706 |

| Hand Grip Strength non dominant hand | 29,8 ± 8,27 | 29,57 ± 11,31 | .941 |

| Mean ± standard deviation of demographic characteristics and clinical features are reported. Differences assessed by independent student t-test. Cm: centimeters; KG: Kilograms; FTT: Finger Tapping Test; tSMS: transcranial static magnetic stimulation. *Significant at p<0.05. | |||

| Outcome variable | Mean (SD) | T0 vs. T1 | T0 vs. T2 | T0 vs. T3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | DM | 95%CI | d | p | DM | 95%IC | d | p | DM | 95%CI | d | p | ||

| Finger Tapping Test | |||||||||||||||||

| 10s | tSMS | 60.25 ± 5.54 | 58.05 ± 5.24 | 60.45 ± 5.9 | 59.85 ± 6.58 | 2.2 ± 1.01 | -.63; 5.03 | .29 | .219 | -.2 ± 1.15 | -3.39; 2.99 | .02 | 1 | .4 ± 1.25 | -3.11; 3.91 | .05 | 1 |

| Sham | 57.85 ± 4.27 | 54.55 ± 6.64 | 56.25 ± 6.5 | 56.75 ± 5.87 | 3.3 ± 1.01 | .47; 6.13 | .42 | .015* | 1.6 ± 1.15 | -1.59; 4,79 | .2 | 1 | 1.1 ± 1.26 | -2.41; 4.61 | .15 | 1 | |

| 5s | tSMS | 31.25 ± 3.8 | 30 ± 2.83 | 31.8 ± 3.15 | 30.8 ± 3.59 | 1.25 ± .52 | -.2; 2.7 | .26 | .131 | -.1 ± -55 | -1.63; 1.43 | .12 | 1 | .45 ± .58 | -1.17; 2.07 | .08 | 1 |

| Sham | 29.6 ± 2.21 | 28.35 ± 4.02 | 29.15 ± 3.17 | 29.05 ± 3.5 | 1.25 ± .52 | -.2; 2.7 | .27 | .131 | .45 ± .5 | -1.08; 1.98 | .12 | 1 | .55 ± .58 | -1.07; 2.17 | .13 | 1 | |

| Nine Hole Peg Test | |||||||||||||||||

| 9HPT | tSMS | 17.51 ± 1.85 | 17.35 ± 2.23 | 16.52 ± 1.99 | 16.57 ± 2.67 | .162 ± .43 | -1.04; 1.36 | .06 | 1 | .99 ± .38 | -.08; 2.06 | .36 | .085 | .933 ± .52 | -.5; 2.37 | .29 | .466 |

| Sham | 17.74 ± 1.74 | 17.54 ± 1.48 | 17.19 ± 1.68 | 17.39 ± 2.25 | .19 ± .43 | -1; 1.39 | .09 | 1 | .54 ± .39 | -.53; 1.61 | .23 | .994 | .35 ± .52 | -1.08; 1.78 | .12 | 1 | |

| Hand Grip Strength | |||||||||||||||||

| HGS | tSMS | 33.93 ± 8.67 | 32.63 ± 7.87 | 33.3 ± 8.48 | 32.53 ± 7.2 | 1.3 ± .71 | -.69; 3.28 | .11 | .466 | .63 ± .76 | -1.49; 2.74 | .05 | 1 | 1.39 ± .89 | -1.09; 3.87 | .01 | .76 |

| Sham | 32.73 ± 11.05 | 32.07 ± 11.58 | 32.73 ± 10.92 | 32.87 ± 10.51 | .67 ± .71 | -1.32; 2.66 | .04 | 1 | .001 ± .76 | -2.12; 2.12 | 0 | 1 | -.13 ± .89 | -2.61; 2.35 | 0 | 1 | |

| Statistical test used: repeated-measures ANOVA. Significance: *p<0.05. d: Cohen’s d; DM: difference of means; HGS: Hand Grip Strength; S: seconds; SD: Standard deviation; tSMS: transcranial static magnetic stimulation; T0: basal; T1: immediately after stimulation; T2: 15 minutes after stimulation; T3: 40 minutes after stimulation; vs: versus; 9HPT: Nine Hole Peg Test. | |||||||||||||||||

| Outcome variable | Mean (SD) | T0 vs. T1 | T0 vs. T2 | T0 vs. T3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | DM | 95%CI | d | p | DM | 95%IC | d | p | DM | 95%CI | d | p | ||

| Finger Tapping Test | |||||||||||||||||

| 10s | tSMS | 53.15 ± 4.45 | 53.2 ± 5.18 | 54.35 ± 3.96 | 54.95 ± 4.48 | -.05 ± .81 | -2.3; 2.2 | 0 | 1 | -1.2 ± .99 | -3.97; 1,57 | .2 | 1 | -1.8 ± .9 | -4.33; .73 | .28 | .329 |

| Sham | 52.4 ± 5.34 | 50.95 ± 5.49 | 52.3 ± 5.25 | 53.4 ± 5.27 | 1.45 ± .81 | -.8; 3.7 | .19 | .484 | .1 ± .1 | -2.67; 2.87 | .01 | 1 | -1. ± .91 | -3.53; 1.53 | .13 | 1 | |

| 5s | tSMS | 28.05 ± 2.76 | 27.65 ± 2.43 | 28.5 ± 2.33 | 28.8 ± 2.42 | .4 ± .53 | -1.1; 1.89 | .11 | 1 | -.45 ± .64 | -2.22; 1.32 | .13 | 1 | -.75 ± .55 | -2.29; .79 | .2 | 1 |

| Sham | 27.35 ± 2.91 | 26.4 ± 3.49 | 26.9 ± 3 | 27.65 ± 2.78 | .95 ± .535 | -.54; 2.44 | .21 | .504 | .45 ± .64 | -1.32; 2.22 | .11 | 1 | -.3 ± .55 | -1.84; 1.24 | .07 | 1 | |

| Nine Hole Peg Test | |||||||||||||||||

| 9HPT | tSMS | 18.84 ± 2.12 | 19.35 ± 2.23 | 18.77 ±2.64 | 17.97 ± 2.74 | -.51 ± .39 | -1.6 ± .58 | .17 | 1 | .06 ± .4 | -1.05; 1.18 | .02 | 1 | .87 ± .37 | -.16; 1.9 | .25 | .144 |

| Sham | 19.61 ± 2.11 | 20.14 ± 2.6 | 19.75 ± 2.57 | 18.79 ± 2.08 | -.53 ± .39 | -1.62; .55 | .16 | 1 | -.15 ± .4 | -1.26; .97 | .04 | 1 | .81 ± .37 | -.22; 1.84 | .28 | .204 | |

| Hand Grip Strength | |||||||||||||||||

| HGS | tSMS | 29.8 ± 8.27 | 29.77 ± 7.27 | 29.97 ± 6.83 | 29.57 ± 6.04 | .032 ± .7 | -1.92; 1.98 | 0 | 1 | -.17 ± .75 | -2.26; 1.92 | .02 | 1 | .32 ± .95 | -2.4; 2.87 | .02 | 1 |

| Sham | 29.57 ± 11.3 | 29.57 ± 10.36 | 29.77 ± 10.2 | 30.2 ±10.68 | .002 ± .7 | -1.95; 1.95 | 0 | 1 | -.2 ± .75 | -2.29; 1.89 | .01 | 1 | -.63 ± .95 | -3.27; 2 | .04 | 1 | |

| Statistical test used: repeated-measures ANOVA. Significance: *p<0.05. d: Cohen’s d; DM: difference of means; HGS: Hand Grip Strength; S: seconds; SD: Standard deviation; tSMS: transcranial static magnetic stimulation; T0: basal; T1: immediately after stimulation; T2: 15 minutes after stimulation; T3: 40 minutes after stimulation; vs: versus; 9HPT: Nine Hole Peg Test. | |||||||||||||||||

| Outcome variable | tSMS | Sham tSMS | DM | 95%CI | d | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finger Tapping Test | ||||||

| T0 – 10 seconds, mean (SD) | 60.25 ± 5.54 | 57.85 ± 4.27 | 2.4 ± 1.57 | -.767; 5.57 | .49 | .133 |

| T1 – 10 seconds, mean (SD) | 58.05 ± 5.24 | 54.55 ± 6.64 | 3.5 ± 1.89 | -.327; 7.33 | .58 | .072 |

| T2 – 10 seconds, mean (SD) | 60.45 ± 5.9 | 56.25 ± 6.5 | 4.2 ± 1.98 | .199; 8.2 | .68 | .04* |

| T3 – 10 seconds, mean (SD) | 59.85 ±6.58 | 56.75 ± 5.87 | 3.1 ± 1.97 | -.89; 7.09 | .5 | .124 |

| T0 – 5 seconds, mean (SD) | 31.25 ± 3.8 | 29.6 ± 2.21 | 1.65 ± .85 | -.064; 3.36 | .53 | .59 |

| T1 – 5 seconds, mean (SD) | 30 ± 2.83 | 28.35 ± 4.02 | 1.65 ± 1.1 | -.57; 3.87 | .47 | .141 |

| T2 – 5 seconds, mean (SD) | 31.8 ± 3.15 | 29.15 ± 3.17 | 2.2 ± 0.99 | .18; 4.22 | .84 | .034* |

| T3 – 5 seconds, mean (SD) | 30.8 ± 3.59 | 29.05 ± 3.5 | 1.75 ± 1.12 | -.52; 4.02 | .48 | .127 |

| Nine Hole Peg Test | ||||||

| T0 – 9HPT, mean (SD) | 17.51 ± 1.85 | 17.74 ± 1.74 | -.23 ± .57 | -1.38; .92 | .13 | .691 |

| T1 – 9HPT, mean (SD) | 17.35 ± 2.23 | 17.54 ± 1.48 | -.19 ± .6 | -1.41; 1.02 | .1 | .744 |

| T2 – 9HPT, mean (SD) | 16.52 ± 1.99 | 17.19 ± 1.68 | -.67 ± .58 | -1.85; .51 | .36 | .256 |

| T3 – 9HPT, mean (SD) | 16.57 ± 2.67 | 17.39 ± 2.25 | -.81 ± .78 | -2.39; .77 | .33 | .306 |

| Hand Grip Strength | ||||||

| T0 – HGS, mean (SD) | 33.93 ± 8.67 | 32.73 ± 11.05 | 1.19 ± 3.14 | -5.16; 7.55 | .12 | .706 |

| T1 – HGS, mean (SD) | 32.63 ± 7.87 | 32.07 ± 11.58 | 0.56 ± 3.13 | -5.78; 6.9 | .06 | .858 |

| T2 – HGS, mean (SD) | 33.3 ± 8.48 | 32.73 ± 10.92 | 0.57 ± 3.09 | -5.69; 6.83 | .06 | .856 |

| T3 – HGS, mean (SD) | 32.53 ± 7.2 | 32.87 ± 10.51 | -0.33 ± 2.85 | -6.1; 5.44 | .04 | .908 |

| Statistical test used: repeated-measures ANOVA. Significance: *p<0.05. d: Cohen’s d; DM: difference of means; HGS: Hand Grip Strength; SD: Standard deviation; tSMS: transcranial static magnetic stimulation; T0: basal; T1: immediately after stimulation; T2: 15 minutes after stimulation; T3: 40 minutes after stimulation; 9HPT: Nine Hole Peg Test. | ||||||

| Outcome variable | tSMS | Sham tSMS | DM | 95%CI | d | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finger Tapping Test | ||||||

| T0 – 10 seconds, mean (SD) | 53.15 ± 4.45 | 52.4 ± 5.34 | .75 ± 1.55 | -2.35; 3.85 | .15 | .632 |

| T1 – 10 seconds, mean (SD) | 53.2 ± 5.18 | 50.95 ± 5.49 | 2.25 ± 1.69 | -1.17; 5.67 | .42 | .19 |

| T2 – 10 seconds, mean (SD) | 54.35 ± 3.96 | 52.3 ± 5.25 | 2.05 ± 1.47 | .93; 5.03 | .44 | .172 |

| T3 – 10 seconds, mean (SD) | 54.95 ± 4.48 | 53.4 ± 5.27 | 1.55 ± 1.55 | -1.58; 4.68 | .32 | .322 |

| T0 – 5 seconds, mean (SD) | 28.05 ± 2.76 | 27.35 ± 2.91 | .7 ± .9 | -1.11; 2.52 | .25 | .44 |

| T1 – 5 seconds, mean (SD) | 27.65 ± 2.43 | 26.4 ± 3.49 | 1.25 ± .95 | -.67; 3.17 | .42 | .196 |

| T2 – 5 seconds, mean (SD) | 28.5 ± 2.33 | 26.9 ± 3 | 1.6 ± .85 | -.122; 3.32 | .6 | .068 |

| T3 – 5 seconds, mean (SD) | 28.8 ± 2.42 | 27.65 ± 2.78 | 1.15 ± .82 | -.52; 2.82 | .44 | .171 |

| Nine Hole Peg Test | ||||||

| T0 – 9HPT, mean (SD) | 18.84 ± 2.12 | 19.61 ± 2.11 | -.76 ± .67 | -2.12; .59 | .36 | .260 |

| T1 – 9HPT, mean (SD) | 19.35 ± 2.23 | 20.14 ± 2.6 | -.79 ± .77 | .2.34; .76 | .33 | .310 |

| T2 – 9HPT, mean (SD) | 18.77 ± 2.64 | 19.75 ± 2.57 | -.97 ± .82 | -2.64; .69 | .38 | .245 |

| T3 – 9HPT, mean (SD) | 17.97 ± 2.74 | 18.79 ± 2.08 | -.82 ± .77 | -2.38; .735 | .34 | .292 |

| Hand Grip Strength | ||||||

| T0 – HGS, mean (SD) | 29.8 ± 8.27 | 29.57 ± 11.3 | .23 ± 3.13 | -6.11; 6.57 | .02 | .941 |

| T1 – HGS, mean (SD) | 29.77 ± 7.27 | 29.57 ± 10.36 | .2 ± 2.83 | -5.53; 5.93 | .02 | .944 |

| T2 – HGS, mean (SD) | 29.97 ± 6.83 | 29.77 ± 10.21 | .2 ± 2.75 | -5.36; 5.76 | .02 | .942 |

| T3 – HGS, mean (SD) | 29.57 ± 6.04 | 30.2 ± 10.68 | -.63 ± 2.74 | -6.19; 4.92 | .07 | .819 |

| Statistical test used: repeated-measures ANOVA. Significance: *p<0.05. d: Cohen’s d; DM: difference of means; HGS: Hand Grip Strength; SD: Standard deviation; tSMS: transcranial static magnetic stimulation; T0: basal; T1: immediately after stimulation; T2: 15 minutes after stimulation; T3: 40 minutes after stimulation; 9HPT: Nine Hole Peg Test. | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).