1. Background and Rationale

Reproduction creates specific nutritional requirements for mothers to ensure the proper growth, development, health, and care of their offspring [

1]. Maternal nutrition during the reproductive period, especially during pregnancy and lactation, is of paramount importance. Inadequate nutrition during pregnancy exposes the child to complications such as intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), low birth weight (LBW), and subsequent infant malnutrition. These children may experience poor physical growth in their early years and fail to achieve their genetic potential. In adolescence, their pubertal growth may be delayed and stunted. The accumulation of these developmental challenges led the World Health Organization (WHO) to commit to several areas of action in its Food and Nutrition Policy Action Plan. The primary focus is to promote a healthy start in life for newborns by ensuring adequate nutrition and food security for pregnant women, thereby improving maternal health and reducing maternal mortality by three-quarters between 1990 and 2015. A key action is to promote optimal fetal nutrition by ensuring good maternal nutrition before conception [

2].

Low birth weight (LBW) alone accounts for 17% of all live births, according to the WHO [

3]. Children born with LBW are 30 times more likely to die than their normal-weight counterparts [

4].

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), despite the establishment of the National Nutrition Program (PRONANUT) and the implementation of standards and guidelines for newborn and young child feeding practices (ANJE), the prevalence of LBW remains a significant concern [

5,

6]. The latest Demographic and Health Survey (EDS-RDC II 2013–2014) reports a national LBW rate of 7%, with a higher rate of 9.2% in Kwango Province [

7]. According to the MICS 2018 report, the LBW rate is 17% in Kwango Province [

8]. Between 2014 and 2018, the number of children born with LBW increased by 90%—a worrying trend that does not meet the WHO’s target of reducing the incidence of LBW by 30% by 2025.

In late June 2022, Yaka organized armed groups, collectively named "Mobondo" after protective amulets. The new militia was mainly armed with machetes, bows, spears, and a smaller number of guns, including a few military assault rifles. The Mobondo began to attack Teke communities, killing civilians and looting property. This conflict between the Téké and Yaka communities in Kwango Province has led to a series of violent incidents, resulting in the displacement of residents from Kwamouth territory in Kwango Province. The adverse effects of conflicts on health, including Food security, have been thoroughly documented, encompassing social, economic, and political ramifications [

9]. In conflict or post-conflict settings, poverty, community breakdown, social and health system disruption, are commonly observed [

10]. The interplay of these factors has a dynamic impact on both the overall food sufficiency and the nutritional value of the diet, particularly during the prenatal phase. Patients residing in conflict-ridden areas may have distinct difficulties, which can intensify their requirement for social assistance. Our study aims to fill the gaps in existing literature by examining the determinants of low birth weight (LBW) in a conflict situation. Specifically, we will explore the association between LBW and Women's dietary diversity in Kenge health zone (HZ), one of the areas affected by the Mobondo Militia, in Kwango province.

2. Methods

An unmatched case–control study was conducted in five healthcare facilities (HCFs) in the Kenge urban–rural HZ in Kwango Province, DRC. This HZ has a total population of 329,802, with an area of 18,126 km2, and has received several displaced persons not well-documented from the conflict in the Kwamouth area.

2.1. Sampling

Non-probabilistic sampling was carried out using Stata 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), with a 95% confidence interval (CI), 80% power, and a case–control ratio of 1:2 (1 case for 2 controls). The sampling assumed a correlation of 0.20 between cases and unmatched controls, with 40% of hypothetical controls born at 2500 g or greater, and an odds ratio (OR) of 62.9% [

11].

After considering the above assumptions, we entered these values into the OpenEpi model to calculate the sample size. Among the three possibilities, we chose the Fleiss continuity correction results, which were rounded to the nearest whole number. This resulted in 53 cases and 106 controls, for a total of 159 children to be studied. The study used non-probabilistic sampling. The sampling sites (Health facilities (HF)) were selected by convenience due to the insecurity in the area following the «Mobondo phenomenon». One HF offering maternity services was selected from each health area (HA), namely, HA Barrière, Saint-Esprit, Pont-Wamba, communauté baptiste du Congo (CBCO), and General Referral Hospital of Kenge. For health areas with more than one maternity facility, the facility with the highest delivery frequency was selected.

2.2. Data Collection

Trained investigators collected data using a data entry form designed with ODK software and then centralized the data on a server. Mothers were interviewed about their antenatal care, lifestyle factors such as tobacco and alcohol use, medical examinations during pregnancy, malaria treatment, and the use of iron folate and other supplements.

Data collection was conducted by 3 master’s students from the Kinshasa School of Public Health (KSPH), using tablets equipped with the ODK program. These students underwent training on research tools, ethics, and linguistic issues. Acting as interviewers, they received guidance on questionnaire administration through two training sessions conducted by the research team as part of their educational curriculum.

Interviews were conducted in Lingala or Kiyaka (the local languages in Kenge) or in French. To ensure linguistic and conceptual equivalency during translation from French to Lingala or Kiyaka, reverse translation was employed, with the assistance of bilingual academics. Information was gathered and analyzed in an anonymous manner, with the survey deliberately excluding personal identifiers of the participants.

2.3. Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to examine the variables. Initially, we determined an overview of the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, both in their entirety and categorized by LBW status. We calculated the Women’s Dietary Diversity Score (WDDS), an indicator of micronutrient adequacy, from a qualitative recall of the previous 24 h diet. This score reflects the number of food groups consumed by women from the following ten groups: starchy staples, dark green leafy vegetables, vitamin A-rich vegetables and fruits, other vegetables and fruits, organ meats, meat/fish, eggs, legumes/nuts, and dairy.

In bivariate analyses, covariates showing associations were entered into a logistic regression model for multivariate analysis, with 95% confidence intervals; after checking for multicollinearity among the covariates, a multivariable logistic regression model was developed. Factors associated with LBW in bivariate analysis were entered into a logistic regression model to obtain adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). ORs and 95% CIs were estimated from regression parameters. Variance inflation factors were calculated to test for multicollinearity, with the highest found to be 2.65. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was carried out in accordance with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. The protocol used in this study received ethical approval from the School of Health Ethics Committee (reference number: ESP/CE/073B/2023). Participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study without any consequences. The master’s students were trained to obtain informed consent. Respondents who could not express themselves in French were offered consent forms in their preferred language. Each participant had the informed consent form read aloud to them and provided verbal consent. To standardize the informed consent process for illiterate participants, we opted for verbal consent witnessed by a third party. The third party ensured that the consent was read to the subject, who then freely agreed to participate in the study. The participant was provided with a signed copy of the consent form to retain. This study did not involve any individuals under the age of 18. Information was gathered and examined in an anonymous manner. The survey form did not include any personal identification of the participants. The participants were notified that their involvement was optional. They had the liberty to accept, decline participation, or withdraw at any time without facing any consequences.

3. Results

A total of 159 mother–infant pairs were included in this study, including 53 cases (infants with a birth weight of <2500 g) and 106 controls (infants with a birth weight of ≥2500 g). Mothers in the case group were younger than those in the control group (mean age: 24 vs. 27 years;

p = 0.003). The proportion of mothers aged 18–25 years was significantly higher in the case group than in the control group (43% vs. 21%;

p = 0.003). In addition, the proportion of mothers with a low level of education was higher in the case group than in the control group (38% vs. 23%;

p = 0.045). The distribution of other characteristics was similar between cases and controls (

Table 1).

3.1. Maternal Clinical and Biological Characteristics

The proportion of mothers who attended at least one antenatal care visit was significantly lower in the case group than in the control group (89% vs. 99%;

p = 0.006). Furthermore, the prevalence of mothers with a height of less than 155 cm was significantly higher in the case group than in the control group (77% vs. 46%;

p < 0.001) (

Table 2).

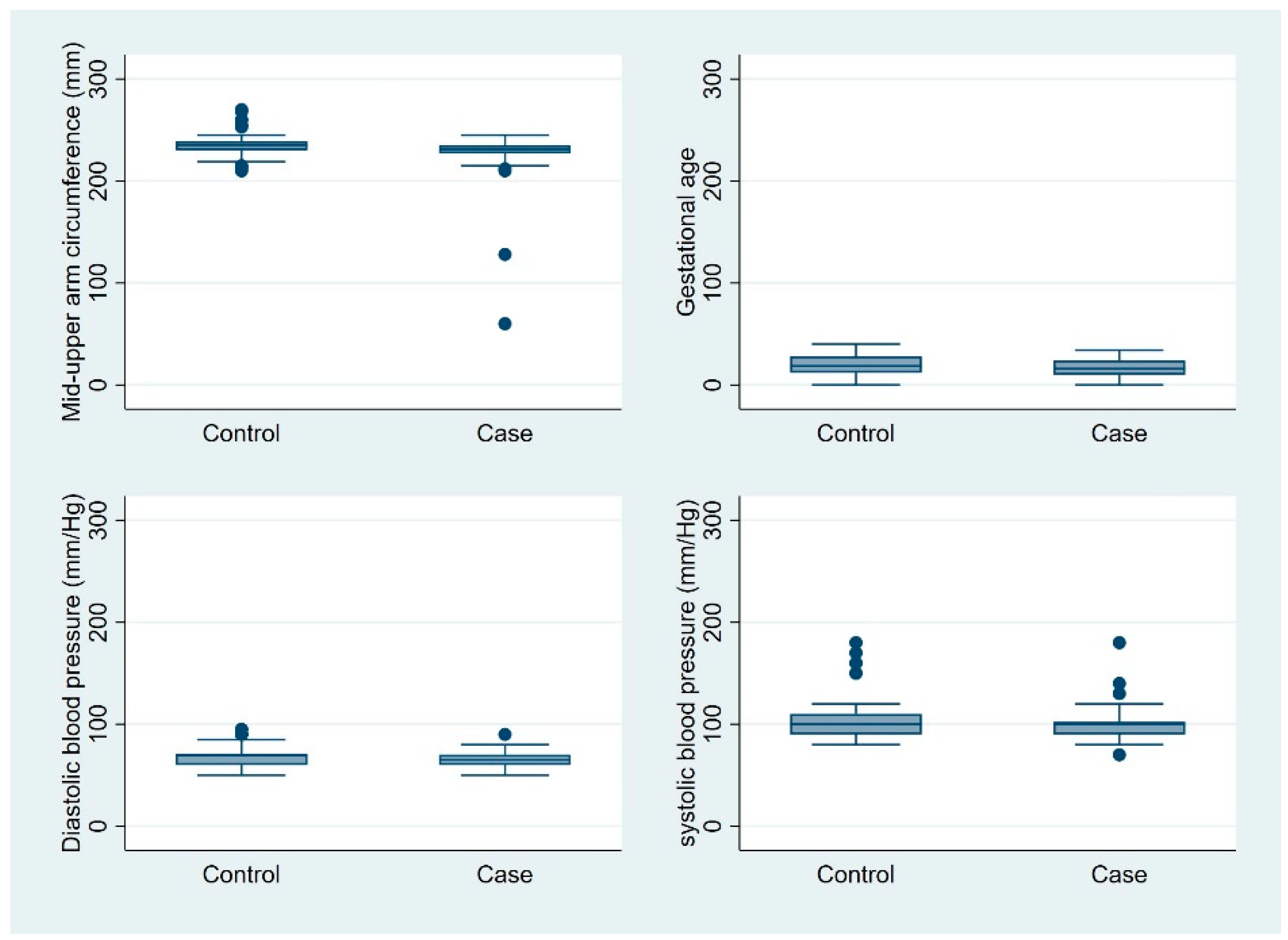

Mothers in the case group had a lower mean number of children than did mothers in the control group (1.89 vs. 2.76;

p = 0.002). In addition, mothers in the case group had fewer antenatal care visits during pregnancy than did mothers in the control group (1.96 vs. 2.31;

p = 0.047). The mean gestational age at delivery was comparable between the two groups (39.18 vs. 39.32 weeks;

p = 0.617). The interbirth interval was slightly shorter for mothers in the case group compared to those in the control group (1.08 vs. 1.45 years;

p = 0.051) (

Figure 1).

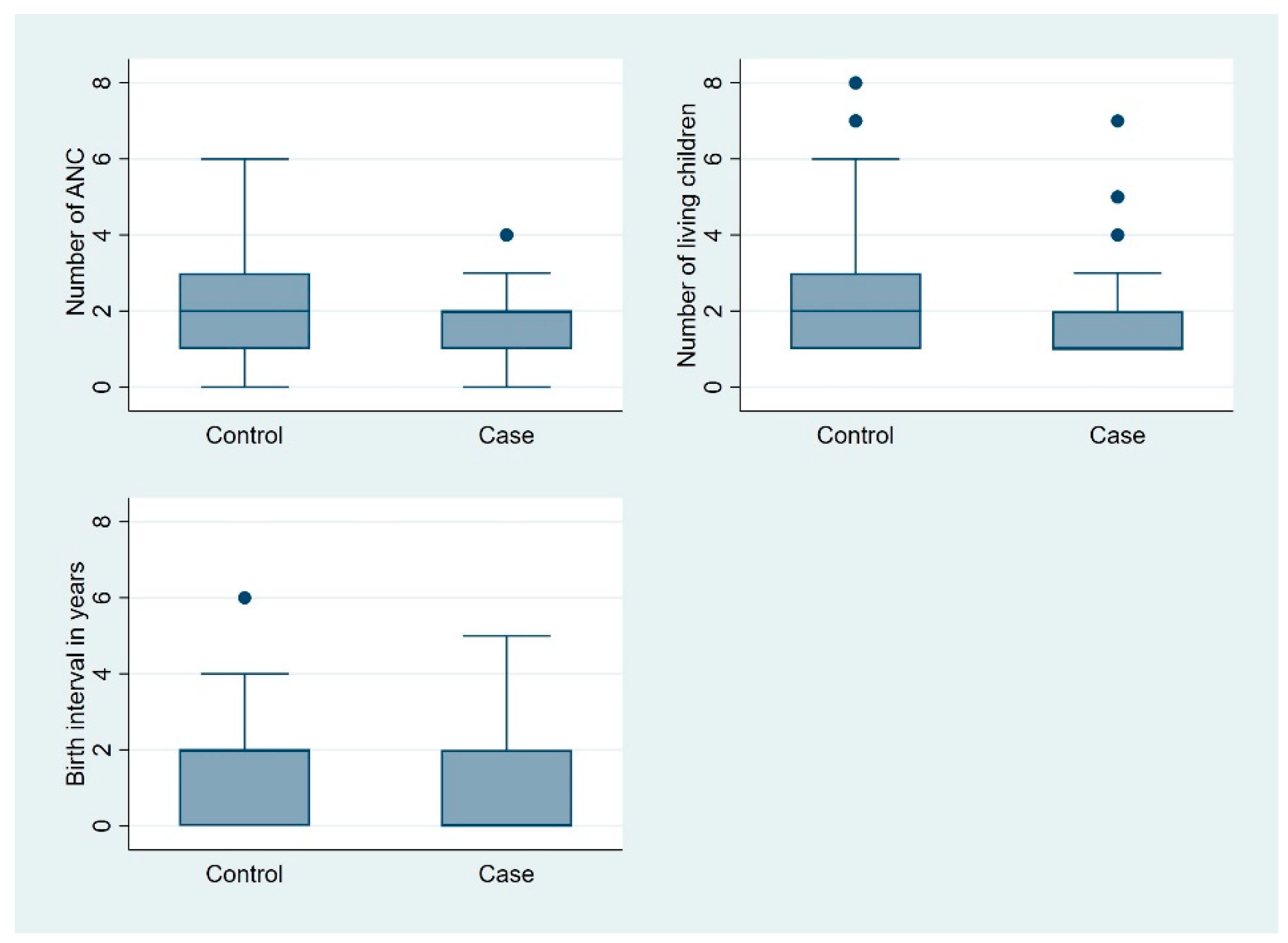

The mean mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) of mothers in the case group was significantly smaller than that of mothers in the control group (225 mm vs. 234 mm;

p = 0.001). The mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures were similar in both groups (

Figure 2). The number of sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP) doses received was lower in the case group than in the control group, although this difference approached but did not reach statistical significance (1.58 vs. 1.92;

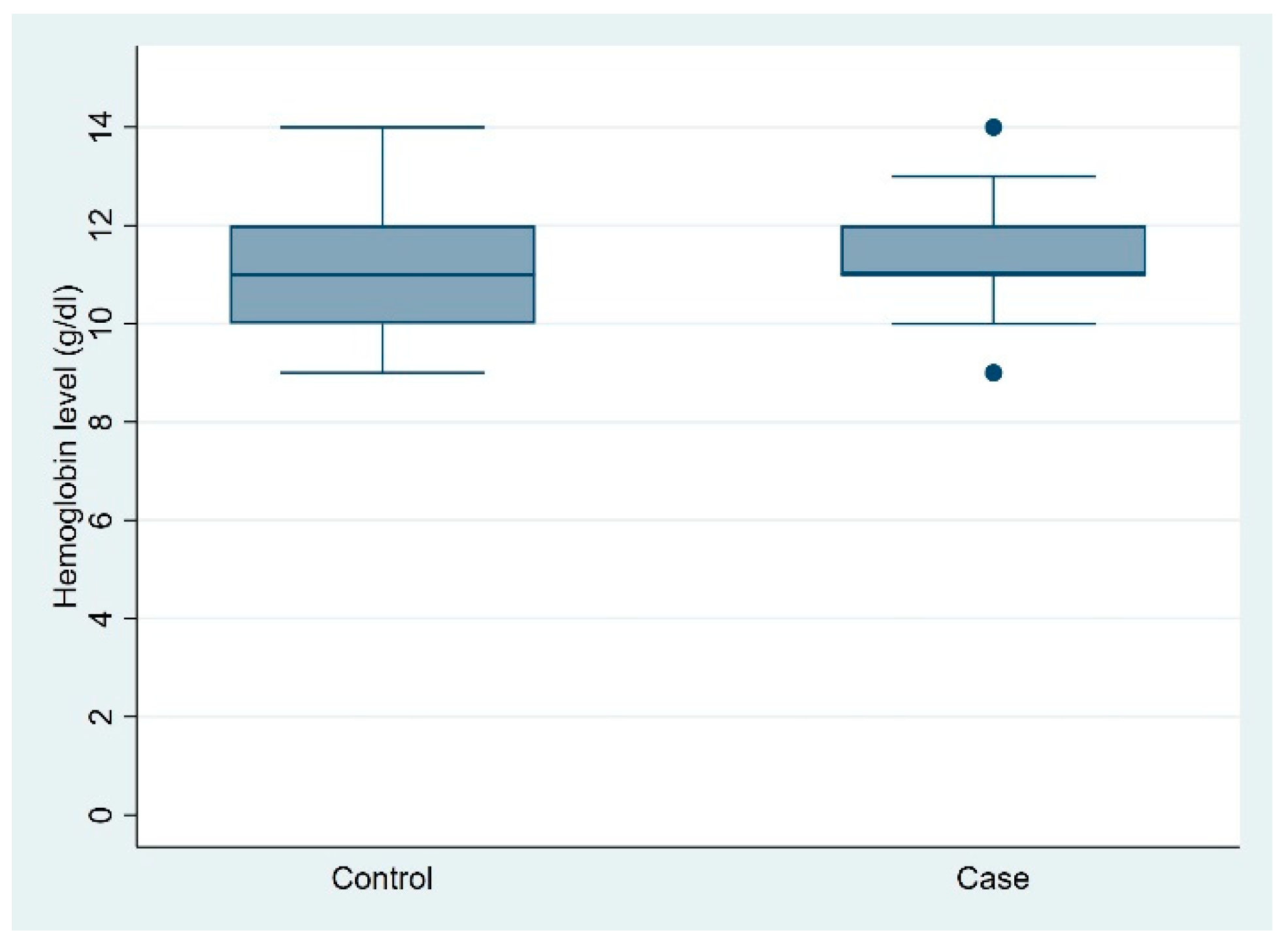

p = 0.050). The mean hemoglobin levels were also similar between the two groups (11.34 vs. 11.03 g/dL;

p = 0.140) (

Figure 3).

3.2. Maternal Dietary Diversity

The Women’s Dietary Diversity Score (WDDS) of mothers in the case group was lower than that of mothers in the control group, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (mean WDDS: 6.51 vs. 6.93;

p = 0.128). Similarly, the proportion of mothers with inadequate minimum dietary diversity was higher in the case group than in the control group, but this difference was also not statistically significant (17% vs. 11%;

p = 0.237) (

Table 3).

3.3. Determinants of Low Birth Weight

In the multivariate analyses, the following variables were identified as determinants of low birth weight (LBW) after adjustment for multicollinearity: number of antenatal care visits, maternal height, ethnic group, and level of dietary diversity.

Mothers who delivered low-birth-weight infants were almost four times more likely to have inadequate dietary diversity compared with those who delivered normal-weight infants (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 3.97; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.25–12.62). Non-indigenous Yaka mothers who delivered low-birth-weight infants were twice as likely to deliver low-birth-weight infants compared to their counterparts who delivered normal-weight infants (AOR: 2.39; 95% CI: 1.01–5.66). Mothers of short stature (less than 155 cm) were nearly four times more likely to deliver low-birth-weight infants compared to mothers of normal stature (AOR: 3.90; 95% CI: 1.66–9.13). In addition, mothers who had fewer antenatal care visits were more likely to give birth to low-birth-weight infants compared with those who had more antenatal care visits (AOR: 0.73; 95% CI: 0.53–0.99) (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

This case–control study conducted in the Kenge Health Zone aimed to identify the determinants of low birth weight (LBW) among term newborns. The study identified several key determinants associated with LBW: small maternal stature (height < 155 cm), non-indigenous Yaka ethnicity, fewer antenatal care visits, and inadequate minimum dietary diversity.

Mothers who delivered LBW infants were significantly more likely to be of short stature compared with taller mothers who delivered normal-weight infants (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 3.90). This finding is consistent with the findings of Berhanu et al. (2020), who reported that mothers with a height of 155 cm or less were more likely to deliver LBW infants (AOR = 3.58; 95% CI: 1.92–6.67) in a study conducted in public health facilities in the North Shewa Zone [

12]. Similarly, Ravi Kumar et al. found that more than half of LBW infants in eastern Nepal were born to mothers with a height of 145 cm or less [

13]. In Kwango Province in general, and in the Kenge Health Zone in particular, short maternal stature results from chronic malnutrition experienced by most women during early childhood due to the poverty that affects the province and the infertile nature of Kwango’s soil, which does not produce high-quality food and limits dietary diversity in households. These factors perpetuate the cycle of malnutrition from early adolescence to the newborn in Kwango. In addition, this study found that inadequate minimum maternal dietary diversity was associated with LBW (AOR: 3.97). This finding is consistent with that of Abubakari et al. in Ghana in 2016, who reported that good dietary diversity and eating habits of women have a protective effect against the delivery of LBW infants [

14]. This can be explained by the fact that in Kenge and Kwango Province, farmers do not diversify their crops, leading to monotonous diets, and cultural practices prohibit certain foods for pregnant women, such as eggs. In addition, farmers often prefer to sell their livestock or agricultural produce rather than consume it themselves.

Mothers who attended fewer antenatal care visits were more likely to have low-birth-weight (LBW) infants than those who attended more visits (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 1.37). This finding is consistent with that of Ravi Kumar et al., who reported that mothers who attended only 1–2 antenatal care visits were 16 times more likely to deliver LBW infants than those who attended more than two visits [

13]. Antenatal care is critical in providing pregnant women with essential guidance and support for a healthy pregnancy and its outcomes.

Despite policies to promote safer motherhood, certain traditions discourage pregnant women from attending early antenatal care services because of fears of malevolent spirits threatening the pregnancy. Geographical barriers, such as the long distance between health facilities and the homes of pregnant women, also discourage attendance at prenatal consultations. Many women prefer to wait until the day of delivery to seek medical attention. Financial difficulties, even for the minimal fees required for antenatal care, further discourage women from seeking these services, despite the low cost in rural Congo. This observation is consistent with the findings of Ignace Bwana in a 2014 study conducted in Kamina, DRC, which showed that pregnant women who did not attend antenatal consultations were more likely to give birth to LBW infants [

15].

This study also found that non-indigenous Yaka mothers have twice the risk of delivering low-birth-weight (LBW) infants compared with indigenous mothers (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 2.39; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.01–5.66). This increased risk can be attributed to the displacement of many women from their home villages to Kenge due to insecurity caused by the Mobondo militia. These displaced women, who are new to Kenge, often lack the financial resources to purchase food, limiting their ability to diversify their diets or grow crops. Similarly, in a 2015 study conducted in eastern Nepal, Ravi Kumar reported an association between LBW and maternal natality, highlighting the broader impact of displacement and resource scarcity on maternal and newborn health [

13]. To combat economic restrictions that lead to inadequate dietary diversity during crises, policymakers and implementing partners should enhance food assistance programs, such as cash transfers and food supply initiatives, focusing on particularly to displaced population

Strengths and Limitations

This study’s findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations. In particular, the non-representativeness of the sample due to non-probabilistic sampling might have introduced selection bias, and the relatively small sample size may limit the power of our analyses. The small sample size was mainly due to the insecurity caused by the Mobondo militia in Kwango Province, particularly in the Kenge Health Zone during our study period, which prevented a random selection of health areas. As a result, health facilities in insecure areas were excluded from our sample.

In addition, we observed variability in the types of scales used to measure newborn weights in the different maternity wards studied, indicating a lack of standardization of measurement tools. Because neonatal weighing was performed in our absence, any inaccuracies in the instruments could have biased the results by introducing information bias (instrument effect). Although 24 h recall methods have established validity and reliability, they often present challenges related to recall bias.

Despite these limitations, a notable strength of this study is the interest that it generates for a more detailed exploration of the determinants of LBW in a region facing both political–administrative and food security challenges. The study highlights the impact of displacement, due to conflict on inadequate dietary diversity and LBW. Prior to this study, there were not any published studies measuring the relationship between dietary diversity and LBW in a (post-) conflict setting.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study are instrumental in identifying modifiable risk factors for low birth weight (LBW) and informing preventive interventions. Emphasizing proper nutrition for young girls of reproductive age and pregnant women and promoting antenatal care during pregnancy are the key interventions highlighted by this research. These findings will help policymakers develop targeted strategies to address LBW, ultimately contributing to reduced fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MJ and APZ.; methodology, MJ, KF and APZ.; software, MJ, KF and APZ.; validation, MJ and APZ.; formal analysis MJ and APZ.; investigation, MJ.; resources, MJ and APZ.; data curation, MJ and APZ.; writing—original draft preparation, MJ, KF and APZ.; writing—review and editing, MJ, KF and APZ.; visualization, MJ and APZ.; supervision, KF and APZ project administration, MJ.; funding acquisition, MJ and APZ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors have received no specific funding for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the KSPH (reference number: ESP/CE/073B/2023). Consent was obtained from each respondent during data collection. Privacy and confidentiality were maintained throughout the study.

Informed Consent Statement

All co-authors consented to the publication of the last version of the present article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used for analysis can be obtained upon reasonable request by writing an email to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all individuals who participated in this study.

Abbreviations

AS: Aire de santé (Health Area); ANJE: Alimentation du nourrisson et du jeune enfant (Infant and Young Child Feeding); CBCO: Communauté Baptiste du Congo (Baptist Community of Congo); CPN: Consultation Prénatale (Antenatal care visit); CSR: Centre de santé de référence (Reference Health Center); DHIS2: District Health Information Software 2; DPS: Division provincial de la santé (Provincial Health Division); EDS: Enquête Démographique et de Santé (Demographic and Health Survey); ESS: Healthcare Facility; FPN: Low Birth Weight (LBW); HGR: General Referral Hospital; CI: Confidence Interval; MICS: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey; MDD-W: Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women; ODK: Open Data Kit; OR: Odds Ratio; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; WHO: World Health Organization; DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo; PTI: Traitement préventif intermittent (Intermittent Preventive Treatment); PRONANUT: Programme national de nutrition (National Nutrition Program); WDDs: Women’s Dietary Diversity Score; ZS: Health Zone (HZ)

References

- Picciano, M.F. Pregnancy and lactation: Physiological adjustments, nutritional requirements and the role of dietary supplements. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 1997S–2002S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touati Mecheri, D. Statut nutritionnel et Sociodémographique d’une Cohorte de Femmes Enceintes d’EL KHROUB. Répercussion sur le Poids de Naissance du Nouveau-né, Algérie, Constantine. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut de la Nutrition de l’Alimentation et des Technologies Agroalimentaires (INAATAA), Université de Mentouri de Constantine, Constantine, Algeria, 2011; 275p. [Google Scholar]

- Letaief, M.; Soltani, M.S.; Ben Salem, K.; Bchir, A. Epidemiologie de l’insuffisance ponderale à la naissance dans le Sahel tunisien. Santé Publique 2001, 13, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ens-Dokkum, N.I.H.; Schreudef, A.M.; Veen, S.; Verloove-Vanhorickt, S.P.; Ronald Brand, R.; Ruys, J.H. Evaluation of the pretem infant: Review of literature on follow-up of pretem and low birth weight infants, Report from the collaborative Project on pretem and Small for gestation age infants (POPS) in the Netherlands. Paediatr. Perinnatal Epidemiol. 1992, 6, 434–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- République Démocratique du Congo, Ministère de la Santé Publique Programme National de Nutrition. FICHES: Alimentation du Nourrisson et du Jeune Enfant (ANJE) en RDC; 2013; Volume 15, pp. 1–23. Available online: https://www.medbox.org/document/drc-alimentation-du-nourrisson-et-du-Jeune Enfant-fiches-techniques (accessed on May 15h, 2024).

- Padonou, G.; Le Port, A.; Cottrell, G.; Guerra, J.; Choudat, I.; Rachas, A.; Bouscaillou, J.; Massougbodji, A.; Garcia, A.; Martin-Prevel, Y. Prematurity, intrauterine growth retardation and low birth weight: Risk factors in a malaria-endemic area in southern Benin. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 108, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministère du Plan et Suivi de la Mise en œuvre de la Révolution de la Modernité (MPSMRM); Ministère de la Santé Publique (MSP); ICF International. Enquête Démographique et de Santé en République Démocratique du Congo 2013–2014; ICF International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- INS. Enquête par Grappes à Indicateurs Multiples, 2017–2018, Rapport de Résultats de l’Enquête; INS: Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mulanga-Kabeya, C.; Bazepeyo, S.E.; Mwamba, J.K.; Butel, C.; Tshimpaka, J.W.; Kashi, M.; et al. Political and socioeconomic instability: how does it affect HIV? A case study in the Democratic Republic of Congo. AIDS 2004, 18, 832–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, S.M.; Robinette, K.L.; Bolton, P.; Cetinoglu, T.; Murray, L.K.; Annan, J.; et al. Stigma Among Survivors of Sexual Violence in Congo:Scale Development and Psychometrics. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2015, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.H.; Sarkis, N.N.; Fikry, S.I. A study of neonatal morbidity and mortality at Damanhour Teaching Hospital Newborn Unit. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2004, 79, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deriba, B.S.; Jemal, K. Determinants of Low Birth Weight among Women Who Gave Birth at Public Health Facilities in North Shewa Zone: Unmatched Case-Control Study. Inq. J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2021, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar, R.K.; Deo, K.K.; Neupane, U.; Chaudhary Bhaskar, S.; Yadav, B.K.; Pokharel, H.P.; Pokharel, P.K. A Case Control Study on Risk Factors Associated with Low-Birth-Weight Babies in Eastern Nepal. Int J Pediatr. 2015, 2015, 807373, Epub 2015 Dec 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abubakari, A.; Jahn, A. Maternal Dietary Patterns and Practices and Birth Weight in Northern Ghana. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0162285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kangulu, I.B.; Umba, E.K.; Nzaji, M.K.; Kayamba, P.K. Risk factors for low birth weight in semi-rural Kamina, Democratic Republic of Congo. Pan Afr Med J. 2014, 17, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).