1. Introduction

In the contemporary global scenario, the substantial increase in the elderly population is accompanied by significant health-related challenges, including an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases and falls. As an individual age, the musculoskeletal system undergoes physiological changes that compromise its functionality, such as the loss of muscle mass and the increase in adipose tissue, which are common in the ageing process [

1,

2,

3]. These changes manifest in a decline in physical abilities, including a reduction in muscle strength, flexibility, agility, coordination and joint mobility. These factors culminate in increased postural instability and, consequently, increase the risk of falls among the elderly [

4,

5,

6]. Aging is a complex interaction of genetic, environmental, nutritional and behavioral factors, resulting in individual variations in the manifestation and progression of this process, affecting both the general well-being and the health and daily functionality of the elderly. To address this variability, targeted interventions with preventive health actions, encouraging healthy habits, can be developed to improve quality of life in older age as an integral part of a health promotion approach to longevity [

7,

8].

In addition, it is important to note that the aging process also brings with it significant changes in the cardiovascular system. Cardiovascular health can be compromised due to stiffening of the arteries, increased blood pressure and other age-related changes. These factors contribute to a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, which in turn can negatively affect the body's ability to maintain balance and respond appropriately to postural challenges, thus increasing the risk of falls among the elderly [

3,

9,

10].

The elderly population therefore faces a high risk in both these aspects: cardiovascular disease and falls. Given this scenario, and the complex interaction between cardiovascular risk factors and falls, anthropometric indicators have emerged as a highly relevant area of research. Instruments such as body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) are gaining prominence in assessing the link between excess weight and cardiovascular risk [

11,

12].

Waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio have emerged as valuable anthropometric metrics for assessing abdominal fat distribution and predicting cardiovascular risks [

13,

14]. On the other hand, the Body Mass Index, widely used as a global indicator of weight status, has limitations, particularly as it does not discriminate between lean mass and body fat. In contrast, WC and WHtR offer a direct approach to assessing abdominal adiposity, an essential consideration for cardiovascular health [

15].

At the same time, the Timed Up and Go Test (TUG) is proving to be an essential tool that is widely used to assess the mobility of the elderly, both clinically and scientifically, due to its simple application and low cost. The TUG not only correlates with overall functional capacity, but also emerges as an important indicator of risk for falls in the elderly and individuals with physical limitations. This assessment encompasses a series of actions, such as getting up from a chair, walking a short distance, turning around and returning to a sitting position [

16,

17].

In this context, this study aims to investigate the associations between anthropometric indicators of cardiovascular risk and performance in the TUG test in elderly participants in public physical activity programs. By exploring these correlations, we aim to deepen our understanding of the complex interactions between body composition, cardiovascular health and physical function in an elderly population that is susceptible to cardiac disorders and mobility problems. The results of this study may provide valuable information for the development of targeted strategies to improve mobility and reduce cardiovascular risks in this vulnerable population, thus contributing to more effective and personalized interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

This was an observational, cross-sectional and analytical study, approved by the Ethics Committee, CAAE: 27116319.1.0000.8044.

The evaluations took place in six different centers of the 60 Up project, a physical activity program for the elderly, promoted by the Municipal Department for the Elderly of Niterói City Hall, RJ, Brazil.

A total of 54 individuals of both genders aged between 60 and 82 were assessed. The individuals were randomly selected from among the project participants and included in the study if they were within the proposed age range, met the inclusion criteria which included volunteers who were lucid, fully aware of the purpose of the research and able to answer the cognitive questions, as well as follow the instructions related to performing the Timed Up and Go Test (TUG), understood and signed the Informed Consent Form. The exclusion criteria involved. The exclusion criteria involved elderly people with functional disabilities, such as the need to use a wheelchair or walking aids such as canes, crutches or walkers, as well as individuals with severe visual or hearing difficulties. People with flu-like symptoms were also excluded, as were those with neurological sequelae, imbalances, vestibular alterations (such as labyrinthitis) and men1tal disorders that made them unable to take part in the study. Anthropometric measurements were taken (weight, height and abdominal circumference). A digital scale, stadiometer and measuring tape graduated in centimeters were used. During this stage, anthropometric data was collected, including WC, WHtR and BMI. anthropometric measurements were obtained using standardized equipment and techniques; the weight and height of the participants were recorded while they were in an upright position, with their arms outstretched at their sides and their feet apart and parallel, without going beyond the hip line, wearing light clothing, barefoot and without any adornment.

An IToknic scale was used to measure weight, while height was measured using a tape measure fixed to the wall. The information collected was used to calculate BMI, determined using the formula BMI = Weight/Height², and the waist-to-height ratio using the formula: WHtR=WH (cm)/WH (cm). Waist circumference (WC) was measured using a tape measure positioned parallel to the ground, placed at the midpoint between the tenth rib and the iliac crest. During the measurement, the volunteer were instructed to exhale completely to ensure that the reading was accurate.

Performing the TUG test:

Each elderly person was initially seated on a chair. An assessor started the timer manually when the word “Go” was said. The participant got up from the chair, walked a predefined distance of 3 meters, walked around a reference object and returned to the chair. The assessor manually recorded the time elapsed from the start to the end of the test for each participant [

17,

18].

As part of the statistical analysis, the Shapiro-Wilk normality test was used to assess the distribution of the data. In addition, Pearson's correlation was applied to investigate possible correlations between anthropometric indicators and the outcomes obtained in the Timed Up and Go (TTUG) test, establishing a significance level of α = 0.05.

3. Results

Between March and July 2023, a sample of 55 elderly individuals underwent a comprehensive assessment. Of this population, a significant proportion (87%) were women. In terms of age group, there was a predominance of individuals classified as young elderly, covering the 60-69 age group, representing 52% of the total.

Table 1 below shows the distribution of participants by age group, together with the results of anthropometric measurements and TTUG expressed as mean 136 and standard deviation:

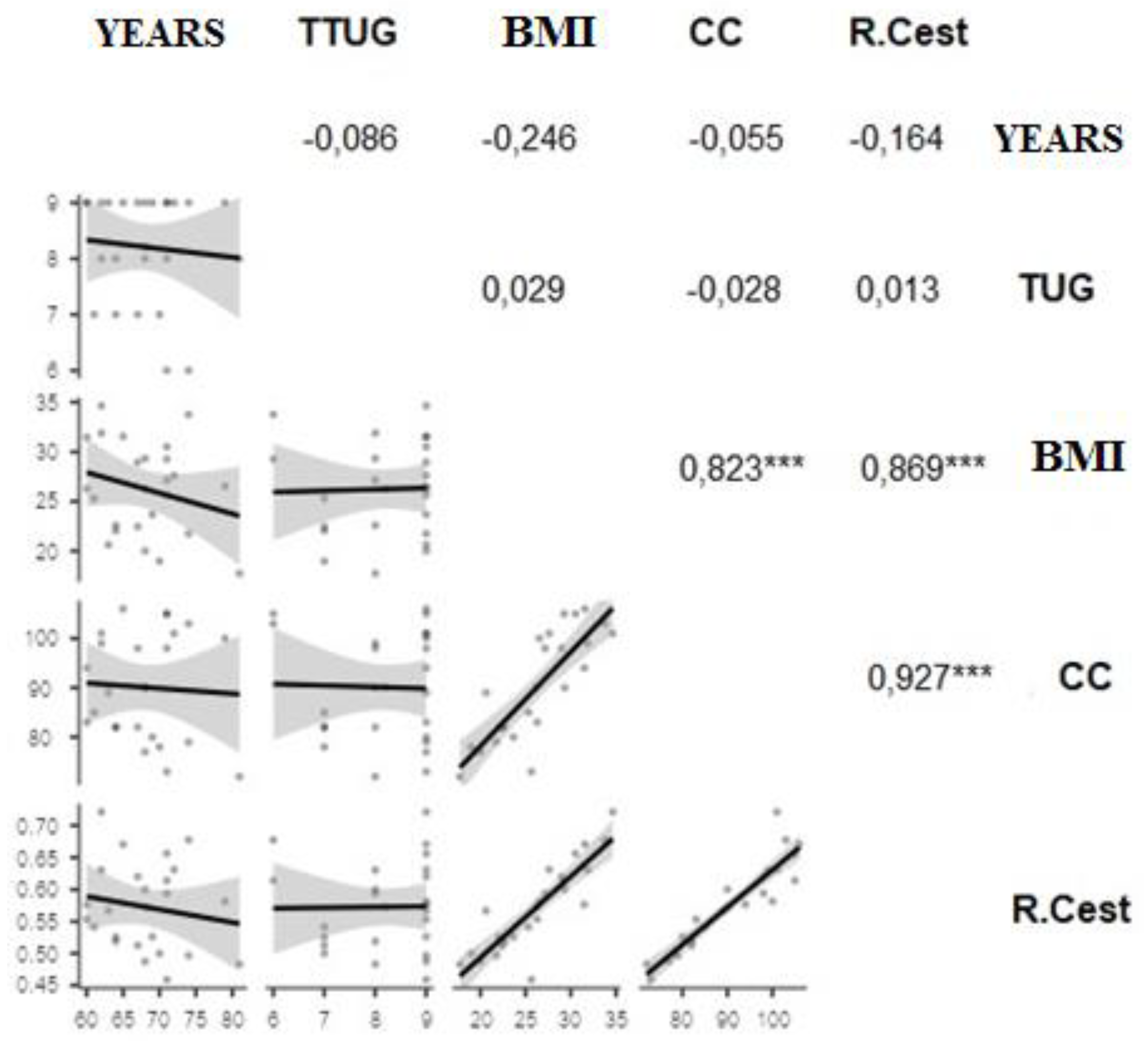

Below, in

Figure 1, are the results of the statistical analysis and the correlations between the times used in the TUG test and four specific variables of the population evaluated: Age, Body Mass Index, Waist Circumference and Waist to Height Ratio, providing a solid basis for future research and interventions aimed at this population.

The correlations that stood out most in this study were the TTUG time in combination with waist circumference and WHtR. This relationship is particularly relevant for understanding the influence of abdominal fat on the functional mobility of elderly people who practice physical activity.

4. Discussion

The relationship between cardiovascular risk factors and anthropometric indicators has raised global health concerns, with a particular focus on abdominal obesity, which has established itself as a wide-ranging epidemic, affecting a variety of age groups and socioeconomic groups [

9,

19].

This scenario is especially relevant among the elderly, where the incidence of abdominal obesity contributes to an increase in the chances of adverse cardiac events. Anthropometric indices such as body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) have emerged as important tools for assessing the cardiovascular risks associated with excess weight [

20].

In parallel, the Timed Up and Go Test (TTUG) has been widely used to assess not only functional mobility, but also the potential risk of falls, especially among the elderly and individuals with physical limitations [

16,

21,

22]. Given this context, the present study sought to explore the correlations between anthropometric indicators of cardiovascular risk (BMI, WC and WHtR) and performance in the TTUG in a sample of elderly people practicing a physical activity program. The results showed that the correlations between the time taken to complete the TUG and the anthropometric indicators varied. A moderate association was observed between the time taken to complete the TTUG and BMI, indicating that factors other than BMI may have a stronger influence on performance in the TTUG. On the other hand, significant correlations were found between TTUG time and waist circumference, as well as between TTUG time and WHtR. These correlations suggest that greater abdominal obesity may be associated with slower performance in the TTUG test, possibly due to mobility and balance limitations.

Several studies have shown that WHtR and WC may be better indicators of CVD risk factors diabetes and dyslipidemia than BMI. However, some studies show that, according to well-established cut-off values, BMI can be considered a more sensitive indicator of hypertension in men and women, while WC and WHtR were better indicators of diabetes and dyslipidemia. A combination of BMI and central obesity measurements was associated with a greater indicator of CVD risk factors than either one alone in both sexes [

9,

14,

20].

Waist circumference has been recognized as a prominent indicator of abdominal adiposity, with a unique ability to predict metabolic changes and cardiovascular disease. Results from comprehensive epidemiological studies consistently highlight the striking links between advancing age, adiposity measured by WHR and the presence of cardiovascular disease. This association goes further, encompassing the prevalence of myocardial infarction, the development of coronary artery disease and an increased risk of events related to the coronary system [

10,

20,

23,

24].

In the ELSA-Brazil study, parameters such as waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, conicity index, lipid accumulation product and visceral adiposity index were analyzed. Specifically, these data approximate the measurement of visceral fat obtained through imaging methods, establishing an association between greater mid-intimal thickness and greater prevalence of abdominal fat. Mid-intimal thickness showed a strong relationship with waist circumference in men, and in women, it also showed a correlation with indicators: WHR, lipid accumulation product and the visceral adiposity index. These conclusions highlight the connection between various indicators of abdominal fat and the intima-media thickness of the carotid arteries [

24].

At the same time, our own study found correlations between WC, WHtR and the TTUG test, highlighting the influence of abdominal fat on the mobility of the elderly. The correlation between TTUG time and waist circumference and WHtR (r = 0.927, p = 0.000) indicates a strong positive correlation between TUG test time and waist circumference and Waist to Height Ratio (WHtR). This strong relationship suggests that abdominal fat may be associated with slower performance in the TUG, which correlates with a higher risk of falls.

Both this study and the work by Eickemberg et al. (2019) highlight the need to assess body fat distribution in order to effectively understand cardiovascular risks, as well as functional capacity and mobility, focusing on 220 different stages of life.

According to a study by Zeng Q, et al, (2014), the ideal cut-off values for BMI are: 24.0 and 23.0 kg/m2; 85.0 and 75.0 cm for WC and 0.50 and 0.48 for WHtR, for men andwomen, respectively. However, as can be seen in

Table 1, the results of the volunteers assessed in this study were higher than those presented in the literature. (2015), a shorter TTUG time is related to better muscle power, gait speed and functional capacity. Conversely, a longer time spent performing the test is directly linked to lower functional mobility, suggesting that individuals are more prone to falls. A normal result is considered when the time taken to complete the TTUG test is less than 10 seconds. A time interval between 10 and 19 seconds indicates a moderate risk of falls for the elderly. The risk of falls is considered high when the time taken exceeds 19 seconds. In a study carried out by Herman; Giladi; Hausdorff, (2011), with a fall clinic cohort, with 265 participants, average age 76 years, the average TUG score was 9.5 seconds, with variations from 5.4 to 15.6 seconds. This time was lower than the average of the results presented here, where advancing age seems to have a minimal impact on the time taken to perform the TTUG (average 10.2 seconds).

As pointed out in the investigations carried out by Pondal and del Ser (2008) and Bohannon (2006), which emphasize the impact of ageing on the mobility and functional capacity of the elderly, the studies indicate a positive correlation between the timetaken to perform the TUG Test and age. Older people tend to take longer to complete the test. This phenomenon can be attributed to the physiological and biomechanical changes that occur over the years, directly influencing the speed and agility of movements. In addition, factors such as reduced muscle mass, decreased strength and loss of flexibility contribute to this observed relationship between ageing and performance in the TTUG.

In our evaluations, in a context of elderly people engaged in regular physical activity, it was observed that the functional mobility capacity of these active elderly individuals is not substantially affected by advancing age, although it is affected by the accumulation of abdominal fat, and a moderate risk of falling assessed by the TTUG time was also observed in the volunteers over 70 years old. The results point to different relationships between TTUG time and the variables studied. There was a moderate negative correlation between BMI, body weight and age (-0.27), indicating that, in the context of this population, older people tend to have slightly lower body weights. Age and BMI show moderate correlations with TTUG time, while waist circumference and WHtR show a strong and significant correlation, indicating a strong association between abdominal fat accumulation and TTUG performance. These results can be attributed to the complexity of the influences that these variables have on functional capacity, with factors such as muscle strength, flexibility and balance also playing crucial roles in TTUG performance, indicating that there is a tendency for TTUG performance time to increase as abdominal fat accumulation, BMI and age increase. It should be noted that, within this specific context of elderly people engaged in public physical activity programs, the correlations found may be shaped by the very nature of the interventions carried out in the programs, which may have a different impact on the factors associated with mobility and physical health assessed in this study. In this context, understanding these relationships can be understood as an effect of public physical activity programs, and can contribute to a more holistic approach to assessing and improving functional capacity in active older people.

A possible limitation of our study is the small sample size of the population evaluated, which makes it advisable to include a larger sample size in future studies. In addition, the cross-sectional design of the study is another limitation identified, as it did not allow us to follow the population assessed over time, thus making it impossible to establish cause and effect relationships. Although we observed some trends, we lack robust evidence to categorically state the existence of significant relationships between the specific variables evaluated. This caveat highlights the intricate complexity of the interactions between the variables in the context of healthy elderly people who practice physical activities, thus emphasizing the urgent need to conduct additional studies on the subject.

5. Conclusions

The study revealed correlations between anthropometric indicators of cardiovascular risk (BMI, waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio) and performance in the TUG Test in the elderly. This scenario suggests that regular physical activity may be contributing to the preservation of mobility functionality in this group, regardless of body weight or age. However, it is prudent to point out that, due to the study's limitations, further research is recommended in order to reach more solid conclusions about these associations in the context of active elderly people. Future studies could further explore these associations and identify additional cardiovascular risk factors that may influence the results of the TTUG.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Marília Salete Tavares; methodology, Marília Salete Tavares; formal analysis, Paulo Henrique Moura and Adalgiza Mafra Moreno; research, Fábio Augusto d'Alegria Tuza; resources, Adalgiza Mafra Moreno; data curation, Sara Lucia Silveira de Menezes; writing-preparation of original draft, Adalgiza Mafra Moreno; writing-revision and editing, Emauel Davi and Adalgiza Mafra Moreno; supervision, Dinah Vasconcelos Terra and Adalgiza Mafra Moreno; All authors have read and agreed with the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade Iguaçu - Nova Iguaçu - Brazil (CAAE number 27116319.1.0000.8044, approved on 16/01/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was also obtained from the patients to publish this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results reported in this study will be available from the corresponding author of the article. Please contact Adalgiza Mafra Moreno email: adalgizamoreno@hotmail.com for access to the data.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Universidade Salgado de Oliveira and Universidade Iguaçu for the administrative and technical support provided during the course of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vicentini de Oliveira D, Costa de Jesus M, Ferreira de Mello J, Renata Saraiva Pivetta N, Roberto Andrade do Nascimento Junior J, Pires Corona L. Composição corporal e estado nutricional de idosos ativos e sedentários: sexo e idade são fatores intervenientes?

- Dawalibi NW, Anacleto GMC, Witter C, Goulart RMM, Aquino R de C de. Envelhecimento e qualidade de vida: análise da produção científica da SciELO. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas). 2013, 30, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva A Da, Almeida GJM, Cassilhas RC, Cohen M, Peccin MS, Tufik S, et al. Equilíbrio, coordenação e agilidade de idosos submetidos à prática de exercícios físicos resistidos. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte [Internet]. 2008, 14, 88–93, Available from: http://www.scielo.br/j/rbme/a/48srZmWt93nBZjy45xBywqG/ [cited 2023 May 2]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Silva A, Porath Azevedo Fassarella B, de Sá Faria B, Moreira El Nabbout TG, Moreira El Nabbout HG, da Costa d’Avila J. Envelhecimento populacional: realidade atual e desafios. Global Academic Nursing Journal [Internet]. 2021, 14, (Sup.3 SE-Reflexão). 88–93, Available from: https://globalacademicnursing.com/index.php/globacadnurs/article/view/171. [Google Scholar]

- Maia BC, Viana PS, Arantes PMM, Alencar MA. Consequências das quedas em idosos vivendo na comunidade. Revista Brasileira de Geriatria e Gerontologia. 2011, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Pondal M, del Ser T. Normative data and determinants for the timed “up and go” test in a population-based sample of elderly individuals without gait disturbances. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy. 2008, 31, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szwarcwald CL, Montilla DER, Marques AP, Damacena GN, de Almeida W da S, Malta DC. Inequalities in healthy life expectancy by Federated States. Rev Saude Publica. 2017, 51, 1S–10S. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares MS, de Menezes SLS, Rodrigues CT, Guimarães TT, Dias LA, de Moura PH, et al. A inserção social do idoso: reflexões sobre a inclusão, saúde e bem-estar. Cuadernos de Educación y Desarrollo [Internet]. 2024 Feb 29;16, e3496. Available from: https://ojs.europubpublications.com/ojs/index.php/ced/article/view/3496.

- Ashwell M, Gibson S. A proposal for a primary screening tool: ‘Keep your waist circumference to less than half your height’. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 207. [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida-Pititto B, Ribeiro-Filho FF, Santos IS, Lotufo PA, Bensenor IM, Ferreira SRG. Association between carotid intima-media thickness and adiponectin in participants without diabetes or cardiovascular disease of the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017, 24, 116–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Després JP, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature 2006, 444, 881–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Bautista L, Franzosi MG, Commerford P, et al. Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27 000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study. The Lancet. 2005, 366, 1640–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti KGMM, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; national heart, lung, and blood institute; American heart association; world heart federation; international atherosclerosis society; and international association for the study of obesity. Circulation. 2009, 120, 1640–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ashwell M, Gunn P, Gibson S. Waist-to-height ratio is a better screening tool than waist circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity reviews. 2012, 13, 275–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lean MEJ, Han TS, Morrison CE. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. Bmj. 1995, 311, 158–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991, 39, 142–8. [Google Scholar]

- Shumway-Cook A, Brauer S, Woollacott M. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go Test. Phys Ther. 2000, 80, 896–903. [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon, RW. Reference values for the timed up and go test: a descriptive meta-analysis. Journal of geriatric physical therapy. 2006, 29, 64–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng Q, He Y, Dong S, Zhao X, Chen Z, Song Z, et al. Optimal cut-off values of BMI, waist circumference and waist: height ratio for defining obesity in Chinese adults. British Journal of Nutrition. 2014, 112, 1735–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Munckhof ICL, Jones H, Hopman MTE, de Graaf J, Nyakayiru J, van Dijk B, et al. Relation between age and carotid artery intima-medial thickness: a systematic review. Clin Cardiol. 2018, 41, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoene D, Wu SMS, Mikolaizak AS, Menant JC, Smith ST, Delbaere K, et al. Discriminative Ability and Predictive Validity of the Timed Up and Go Test in Identifying Older People Who Fall: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc [Internet]. 2013, 61, 202–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsiadlo BScPT DRMD. The Timed “Up & Go”: A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons - Podsiadlo - 1991 - Journal of the American Geriatrics Society - Wiley Online Library. 2021, Available from: https://agsjournals-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.translate.goog/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x?_x_tr_sl=en&_x_tr_tl=pt&_x_tr_hl=pt-BR&_x_tr_pto=ajax,se,op.

- Bertoluci MC, Forti AC e, Pititto B de A, Vancea DMM, Malerbi FEK, Valente F, et al. Diretriz Oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes. Diretriz Oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes. 2022 Feb 4.

- Eickemberg M, Amorim LDAF, Almeida M da CC de, Aquino EML de, Fonseca M de JM da, Santos I de S, et al. Indicators of abdominal adiposity and carotid intima-media thickness: results from the Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brazil). Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019, 112, 220–7. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).