Submitted:

05 June 2024

Posted:

05 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Narrative Process

3. Results

- Writing the memoir

- Memoir author meeting the illustrator and the publisher

- Memoir author explaining the graphic memoir to the illustrator and publisher

- Collaborative process of creating the illustrations

- Editing the graphic memoir

- Publishing the graphic memoir.

3.1. When the Pivotal Points Occurred

3.2. Where the Pivotal Points Occurred

3.3. Who Was Involved in the Pivotal Points

3.4. What Occurred in the Pivotal Points

3.5. How the Pivotal Points Occurred

3.6. Why the Pivotal Points Occurred

4. Discussion

4.1. Five Ingredients of Successful Interventions

4.1.1. Long-term

4.1.2. Tailored

4.1.3. Mindfulness-based

4.1.4. Psychosocial Assistance

4.1.5. Physical Health

4.2. Meeting the Intention and the Five Requirements

4.3. Psychoanalytic Narrative Research as the Historical Method

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Future Directions in Publishing the Graphic Memoir

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nguyen, T.; Li, X. Understanding Public-Stigma and Self-Stigma in the Context of Dementia: A Systematic Review of the Global Literature. Dementia 2020, 19, 148–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stites, S.D.; Largent, E.A.; Johnson, R.; Harkins, K.; Karlawish, J. Effects of Self-Identification as a Caregiver on Expectations of Public Stigma of Alzheimer’s Disease. ADR 2021, 5, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.-T.; Li, K.-K.; Losada, A.; Zhang, F.; Au, A.; Thompson, L.W.; Gallagher-Thompson, D. The Effectiveness of Nonpharmacological Interventions for Informal Dementia Caregivers: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychology and Aging 2020, 35, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, H. Acceptance and Commitment Improve the Work–Caregiving Interface among Dementia Family Caregivers. Psychology and Aging 2022, 37, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atefi, G.L.; De Vugt, M.E.; Van Knippenberg, R.J.M.; Levin, M.E.; Verhey, F.R.J.; Bartels, S.L. The Use of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in Informal Caregivers of People with Dementia and Other Long-Term or Chronic Conditions: A Systematic Review and Conceptual Integration. Clinical Psychology Review 2023, 105, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulff, J.; Fänge, A.M.; Lethin, C.; Chiatti, C. Self-Reported Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety among Informal Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: A Cross-Sectional Comparative Study between Sweden and Italy. BMC Health Serv Res 2020, 20, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera-Caballero, S.; Romero-Moreno, R.; Del Sequeros Pedroso-Chaparro, M.; Olmos, R.; Vara-García, C.; Gallego-Alberto, L.; Cabrera, I.; Márquez-González, M.; Olazarán, J.; Losada-Baltar, A. Stress, Cognitive Fusion and Comorbid Depressive and Anxiety Symptomatology in Dementia Caregivers. Psychology and Aging 2021, 36, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gérain, P.; Zech, E. Do Informal Caregivers Experience More Burnout? A Meta-Analytic Study. Psychology, Health & Medicine 2021, 26, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avargues-Navarro, M.L.; Borda-Mas, M.; Campos-Puente, A.D.L.M.; Pérez-San-Gregorio, M.Á.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Sánchez-Martín, M. Caring for Family Members With Alzheimer’s and Burnout Syndrome: Impairment of the Health of Housewives. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lappalainen, P.; Keinonen, K.; Pakkala, I.; Lappalainen, R.; Nikander, R. The Role of Thought Suppression and Psychological Inflexibility in Older Family Caregivers’ Psychological Symptoms and Quality of Life. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 2021, 20, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishita, N.; Contreras, M.L.; West, J.; Mioshi, E. Exploring the Impact of Carer Stressors and Psychological Inflexibility on Depression and Anxiety in Family Carers of People with Dementia. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 2020, 17, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnelli, A.; Karrer, M.; Mayer, H.; Zeller, A. Aggressive Behaviour of Persons with Dementia towards Professional Caregivers in the Home Care Setting—A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2023, 32, 4541–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, A.P.; Buckley, M.M.; Cryan, J.F.; Ní Chorcoráin, A.; Dinan, T.G.; Kearney, P.M.; O’Caoimh, R.; Calnan, M.; Clarke, G.; Molloy, D.W. Informal Caregiving for Dementia Patients: The Contribution of Patient Characteristics and Behaviours to Caregiver Burden. Age and Ageing 2020, 49, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimeno, I.; Val, S.; Cardoso Moreno, M.J. Relation among Caregivers’ Burden, Abuse and Behavioural Disorder in People with Dementia. IJERPH 2021, 18, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, R.; Tan, J.Y.S.; Hum, A.Y.M. Factors Associated With Family Caregiver Burden of Home-Dwelling Patients With Advanced Dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2022, 23, 1248–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinyopornpanish, K.; Wajatieng, W.; Niruttisai, N.; Buawangpong, N.; Nantsupawat, N.; Angkurawaranon, C.; Jiraporncharoen, W. Violence against Caregivers of Older Adults with Chronic Diseases Is Associated with Caregiver Burden and Depression: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Geriatr 2022, 22, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gérain, P.; Zech, E. A Harmful Care: The Association of Informal Caregiver Burnout With Depression, Subjective Health, and Violence. J Interpers Violence 2022, 37, NP9738–NP9762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeza, P.; Rodrigues, M.; Costa, J.; Guerreiro, M.; Rosa, M.M. Impact of Dementia on Informal Care: A Systematic Review of Family Caregivers’ Perceptions. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020, bmjspcare-2020-002242. [CrossRef]

- Nemcikova, M.; Katreniakova, Z.; Nagyova, I. Social Support, Positive Caregiving Experience, and Caregiver Burden in Informal Caregivers of Older Adults with Dementia. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1104250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, L.-F.; Purwaningrum, F. Negative Stereotypes, Fear and Social Distance: A Systematic Review of Depictions of Dementia in Popular Culture in the Context of Stigma. BMC Geriatr 2020, 20, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwar, L.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Matschinger, H.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; König, H.-H.; Hajek, A. Public Stigma towards Informal Caregiving in Germany: A Descriptive Study. Aging & Mental Health 2021, 25, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iancu, A.E.; Rughiniș, C. Emotional Socialization and Agency: Representations of Coping with Old Age Dementia and Alzheimer’s in Graphic Novels. Sociologie Românească 2022, 20, 69–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsimani, P.; Montgomery, A.; Georganta, K. The Relationship Between Burnout, Depression, and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff Burn-Out. Journal of Social Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Tavella, G. Distinguishing Burnout from Clinical Depression: A Theoretical Differentiation Template. Journal of Affective Disorders 2021, 281, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias, C.E.; Cabrera, E.; Zabalegui, A. Informal Caregivers’ Roles in Dementia: The Impact on Their Quality of Life. Life 2020, 10, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jütten, L.H.; Mark, R.E.; Sitskoorn, M.M. Predicting Self-Esteem in Informal Caregivers of People with Dementia: Modifiable and Non-Modifiable Factors. Aging & Mental Health 2020, 24, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddock, A.; Blair, C. How Do Mindfulness-Based Programmes Improve Anxiety, Depression and Psychological Distress? A Systematic Review. Curr Psychol 2023, 42, 10200–10222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellis, E.; Mukaetova-Ladinska, E.B. Informal Caregiving and Alzheimer’s Disease: The Psychological Effect. Medicina 2022, 59, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ji, M.; Leng, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. Comparative Efficacy of 11 Non-Pharmacological Interventions on Depression, Anxiety, Quality of Life, and Caregiver Burden for Informal Caregivers of People with Dementia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2022, 129, 104204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.-T.; Zhang, F. A Comprehensive Meta-Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses on Nonpharmacological Interventions for Informal Dementia Caregivers. BMC Geriatr 2020, 20, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, S.; Ferreira, A.; Paúl, C. Access and Retention of Informal Dementia Caregivers in Psychosocial Interventions: A Cross-Sectional Study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 2021, 93, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, C.; Lautenschläger, S.; Meyer, G.; Stephan, A. Interventions to Support People with Dementia and Their Caregivers during the Transition from Home Care to Nursing Home Care: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2017, 71, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleijlevens, M.H.C.; Stolt, M.; Stephan, A.; Zabalegui, A.; Saks, K.; Sutcliffe, C.; Lethin, C.; Soto, M.E.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; the RightTimePlaceCare Consortium Changes in Caregiver Burden and Health-related Quality of Life of Informal Caregivers of Older People with Dementia: Evidence from the European RightTimePlaceCare Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2015, 71, 1378–1391. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.; Agbata, I.N.; Canavan, M.; McCarthy, G. Effectiveness of Educational Interventions for Informal Caregivers of Individuals with Dementia Residing in the Community: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials: Dementia Caregiver Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015, 30, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, E.; Pinquart, M. How Effective Are Dementia Caregiver Interventions? An Updated Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. The Gerontologist 2020, 60, e609–e619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lethin, C.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Bleijlevens, M.H.; Stephan, A.; Martin, M.S.; Nilsson, K.; Nilsson, C.; Zabalegui, A.; Karlsson, S. Predicting Caregiver Burden in Informal Caregivers Caring for Persons with Dementia Living at Home – A Follow-up Cohort Study. Dementia 2020, 19, 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, A.; Caljouw, M.A.A.; Van Der Ploeg, E.S. Keeping the Person with Dementia and the Informal Caregiver Together: A Systematic Review of Psychosocial Interventions. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2017, 29, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, D.S.K.; Tang, S.K.; Ho, K.H.M.; Jones, C.; Tse, M.M.Y.; Kwan, R.Y.C.; Chan, K.Y.; Chiang, V.C.L. Strategies to Engage People with Dementia and Their Informal Caregivers in Dyadic Intervention: A Scoping Review. Geriatric Nursing 2021, 42, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoel, V.; Koh, W.Q.; Sezgin, D. Enrichment of Dementia Caregiving Relationships through Psychosocial Interventions: A Scoping Review. Front. Med. 2023, 9, 1069846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, B.; Lindsay, E.K.; Greco, C.M.; Brown, K.W.; Smyth, J.M.; Wright, A.G.C.; Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness Interventions Improve Momentary and Trait Measures of Attentional Control: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 2021, 150, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, B.; Eichel, K.; Lindahl, J.R.; Rahrig, H.; Kini, N.; Flahive, J.; Britton, W.B. The Contributions of Focused Attention and Open Monitoring in Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Affective Disturbances: A 3-Armed Randomized Dismantling Trial. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, E.; Witkiewitz, K. Dismantling Mindfulness-Based Programs: A Systematic Review to Identify Active Components of Treatment. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 2470–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puolakanaho, A.; Tolvanen, A.; Kinnunen, S.M.; Lappalainen, R. A Psychological Flexibility -Based Intervention for Burnout:A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 2020, 15, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, N.R.; Judge, K.S.; Lucas, K.; Gowan, T.; Stutz, P.; Shan, M.; Wilhelm, L.; Parry, T.; Johns, S.A. Feasibility and Acceptability of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Intervention for Caregivers of Adults with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. BMC Geriatr 2021, 21, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankland, R.; Tessier, D.; Strub, L.; Gauchet, A.; Baeyens, C. Improving Mental Health and Well-Being through Informal Mindfulness Practices: An Intervention Study. Applied Psych Health & Well 2021, 13, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physical Fitness: Definitions and Distinctions for Health-Related Research. Public Health Reports (1974-) 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Piggin, J. What Is Physical Activity? A Holistic Definition for Teachers, Researchers and Policy Makers. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, S.; Saji, S. Drawing the Mind: Aesthetics of Representing Mental Illness in Select Graphic Memoirs. Health (London) 2021, 25, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J. Special Exits: A Graphic Memoir; Fantagraphics Books ; Turnaround [distributor]: Seattle, Wash. : London, 2010; ISBN 978-1-60699-381-1.

- Garden, R.; Lamb, E.G. Revising the Dementia Imaginary: Disability and Age-Studies Perspectives on Graphic Narratives of Dementia. In The Palgrave Handbook of Literature and Aging; Lipscomb, V.B., Swinnen, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; pp. 97–119 ISBN 978-3-031-50916-2.

- Leavitt, S. Tangles: A Story about Alzheimer’s, My Mother, and Me; 1st publ.; Jonathan Cape: London, 2011; ISBN 978-0-224-09422-1.

- Kuo, H.-J. Alzheimer’s Disease and the Ethics of Care in the Graphic Memoir Tangles: A Story About Alzheimer’s, My Mother, and Me. sli 2019, 52, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, S.; Das, L. Person-Centered Care, Dementia and Graphic Medicine. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine 2022, 45, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovan, S.B.; Soled, D.R. A Disembodied Dementia: Graphic Medicine and Illness Narratives. J Med Humanit 2023, 44, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesan, S.; Ancy A, L. ‘There Were Days I Felt Empty’: Care, Affect, and Graphic Medicine. Visual Studies 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, S.; Ancy A., L. Care as a Creative Practice: Comics, Dementia and Graphic Medicine. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine 2023, 46, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walrath, D. Aliceheimer’s: Alzheimer’s Through the Looking Glass; Penn State University Press, 2016; ISBN 978-0-271-08880-8.

- Roca, P. Wrinkles; First Fantagraphics Books edition.; Fantagraphics Books: Seattle, 2016; ISBN 978-1-60699-932-5.

- Das, L.; Venkatesan, S. “Inside Out of Mind”: Alternative Realities, Dementia and Graphic Medicine. J Med Humanit 2024, 45, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

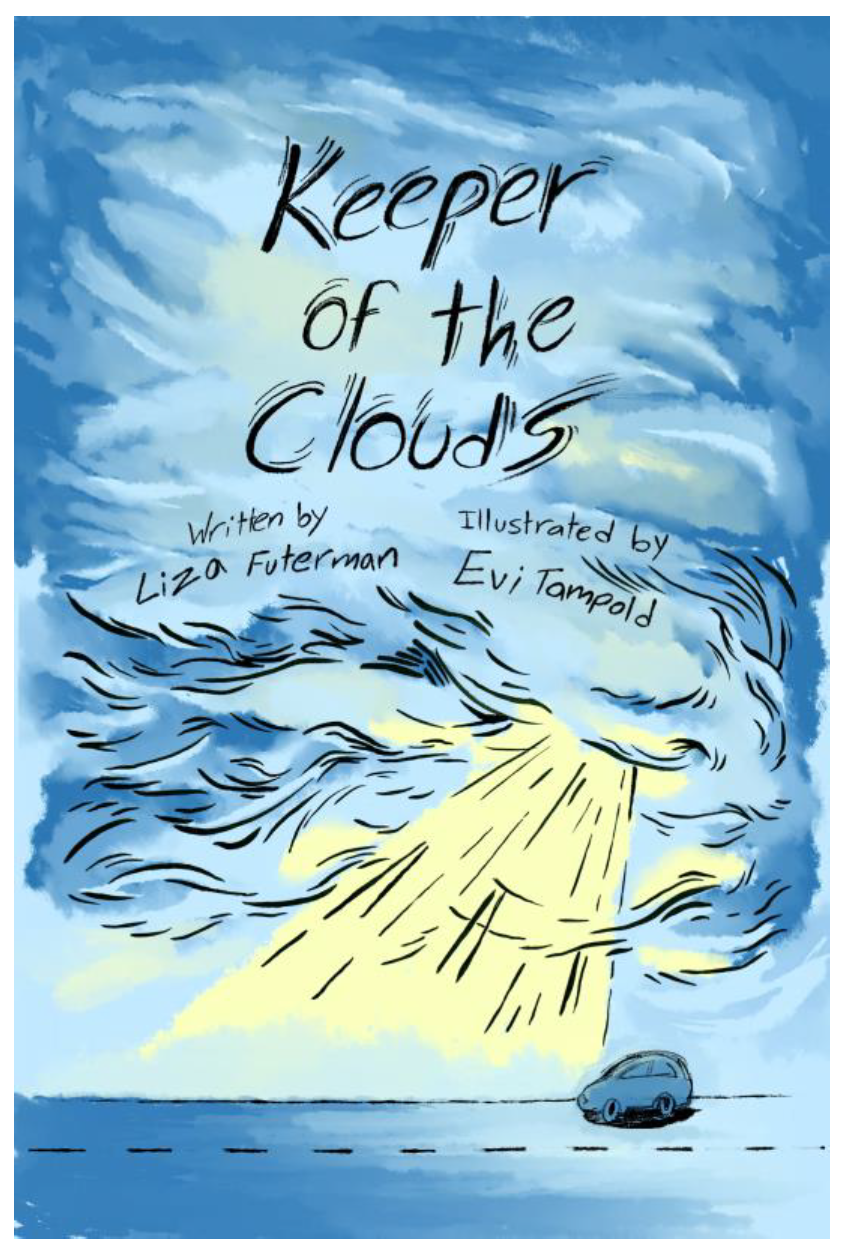

- Futerman, L. Keeper of the Clouds; Tampold Publishing: Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2016; ISBN 978-0-9948329-1-7.

- Silva, M.; Cain, K. The Use of Questions to Scaffold Narrative Coherence and Cohesion. Journal Research in Reading 2019, 42, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fina, A. Doing Narrative Analysis from a Narratives-as-Practices Perspective. NI 2021, 31, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntinda, K. Narrative Research. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2018; pp. 1–13 ISBN 978-981-10-2779-6.

- Renjith, V.; Yesodharan, R.; Noronha, J.A.; Ladd, E.; George, A. Qualitative Methods in Health Care Research. Int J Prev Med 2021, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fludernik, M. The Diachronization of Narratology: Dedicated to F. K. Stanzel on His 80th Birthday. Narrative 2003, 11, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, P. Psychoanalytic Constructions and Narrative Meanings. Paragraph 1986, 7, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Godzich, W. Story and Situation: Narrative Seduction and the Power of Fiction; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 1984; ISBN 978-0-8166-8204-1.

- Guerra, A.M.C.; De Oliveira Moreira, J.; De Oliveira, L.V.; E Lima, R.G. The Narrative Memoir as a Psychoanalytical Strategy for the Research of Social Phenomena. PSYCH 2017, 08, 1238–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, S.-A. Narratology and Narrative Theory. In The Routledge Handbook of Translation History; Routledge: London, 2021; pp. 54–69 ISBN 978-1-315-64012-9.

- Birke, D.; Von Contzen, E.; Kukkonen, K. Chrononarratology: Modelling Historical Change for Narratology. Narrative 2022, 30, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, C.; Berger, S.; Brauch, N. Narrativity and Historical Writing: Introductory Remarks. In Analysing Historical Narratives; Berger, S., Brauch, N., Lorenz, C., Eds.; Berghahn Books, 2022; pp. 1–26 ISBN 978-1-80073-047-2.

- Eiranen, R.; Hatavara, M.; Kivimäki, V.; Mäkelä, M.; Toivo, R.M. Narrative and Experience: Interdisciplinary Methodologies between History and Narratology. Scandinavian Journal of History 2022, 47, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. The Health Narratives Research Group (HeNReG): A Self-Direction Process Offered to Help Decrease Burnout in Public Health Nurse Practitioners. AIMS Public Health 2024, 11, 176–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, C. Report on Digital Literacy in Academic Meetings during the 2020 COVID-19 Lockdown. Challenges 2020, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Online Meeting Challenges in a Research Group Resulting from COVID-19 Limitations. Challenges 2021, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Enhancing Hopeful Resilience Regarding Depression and Anxiety with a Narrative Method of Ordering Memory Effective in Researchers Experiencing Burnout. Challenges 2022, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Team Mindfulness in Online Academic Meetings to Reduce Burnout. Challenges 2023, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, Z.U.; Salek, S.; Finlay, A.Y. Concept of Major Life-Changing Decisions in Life Course Research. In Current Problems in Dermatology; Linder, M.D., Kimball, A.B., Eds.; S. Karger AG, 2013; Vol. 44, pp. 52–66 ISBN 978-3-318-02403-6.

- Alvesson, M.; Einola, K. Warning for Excessive Positivity: Authentic Leadership and Other Traps in Leadership Studies. The Leadership Quarterly 2019, 30, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willig, C. Interpretation in Qualitative Research. In The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology; Sage: London, 2017; pp. 274–288 ISBN 978 1-4739-2521-2.

- Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto Events. PsychNews 2015.

- Futerman, L. Keeper of the Clouds. CMAJ 2017, 189, E27–E27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, L.; Venkatesan, S. Of Comics and Dementia: An Interview with Nigel Baines, Rebecca Roher, and Liza Futerman. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 2024, 15, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D. Stylistics, Narratology, and Point of View: Partiality, Complementarity, and a New Definition. Style 2023, 57, 415–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M. Quality Indicators in Narrative Research. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2021, 18, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futerman, L.; Nash, C. Liza from the Graphic Medicine Panel Last Wednesday (1st Email) 2015.

- Futerman, L.; Nash, C. Liza from the Graphic Medicine Panel Last Wednesday (Last Email) 2015.

- Futerman, L.; Nash, C. Thank You Notes and Summary (Email) 2016.

- Futerman, L.; Nash, C. How Did It Go? (Email) 2016.

- Nash, C.; Dort, B.; Medan, B. A New Book by Evi Tampold (Ten Day Email Thread) 2016.

- Nash, C.; Adelaars, J.; Fraser, V. Keeper of the Clouds (38 Day Email Thread) 2016.

- Futerman, L. At Home St Joseph Street, Toronto (Messenger) 2024.

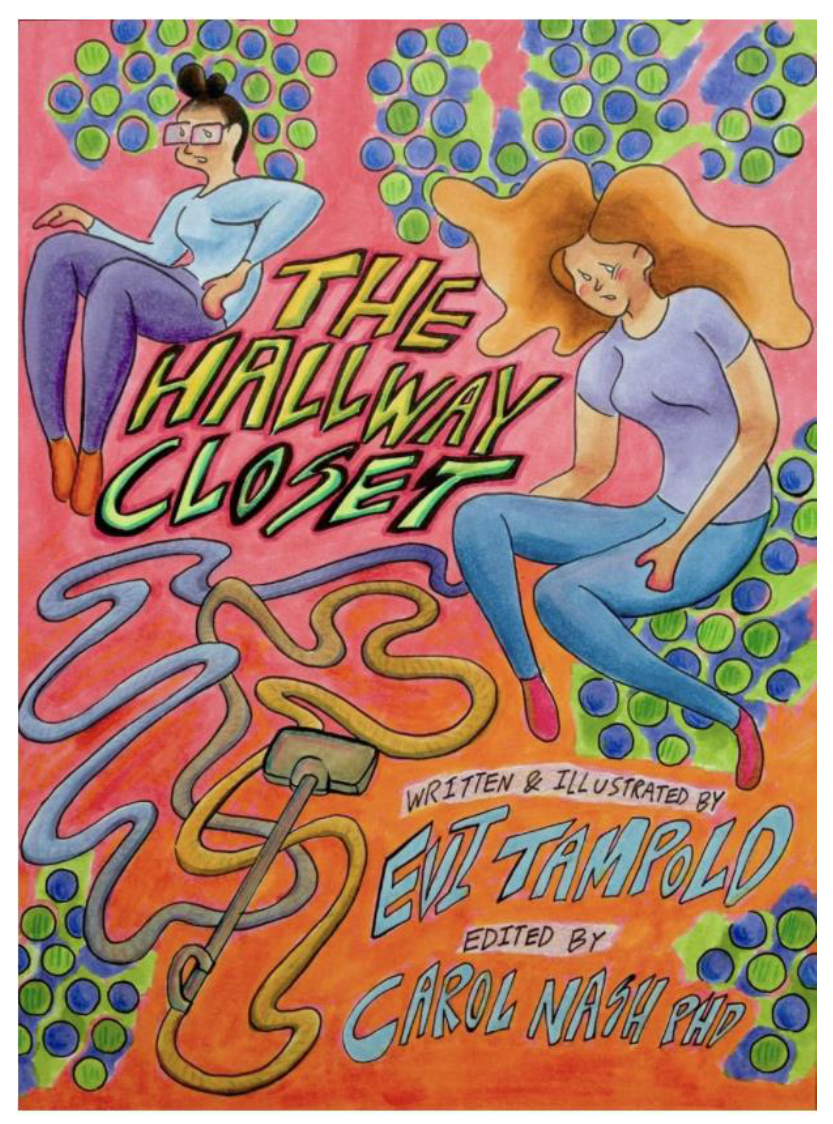

- Tampold, E. The Hallway Closet; Nash, C., Ed.; Tampold Publishing: Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2015; ISBN 978-0-9948329-0-0.

- De Stefano, A.; Rusciano, I.; Moretti, V.; Scavarda, A.; Green, M.J.; Wall, S.; Ratti, S. Graphic Medicine Meets Human Anatomy: The Potential Role of Comics in Raising Whole Body Donation Awareness in Italy and beyond. A Pilot Study. Anatomical Sciences Ed 2023, 16, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.J.; Callender, B. Graphic Medicine—The Best of 2021. JAMA 2021, 326, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwiec, M.K.; Williams, I.; Squier, S.M.; Green, M.J.; Myers, K.R.; Smith, S.T. Graphic Medicine Manifesto; Graphic medicine; The Pennsylvania State University Press: University Park, Pennsylvania, 2015; ISBN 978-0-271-06649-3.

- Green, M.J.; Wall, S. Graphic Medicine—The Best of 2020. JAMA 2020, 324, 2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, C. Evi Tampold Interview 2024.

- Sripada, C.; Taxali, A. Structure in the Stream of Consciousness: Evidence from a Verbalized Thought Protocol and Automated Text Analytic Methods. Consciousness and Cognition 2020, 85, 103007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochrane, A.K.; Mah, K.; Ståhl, A.; Núñez-Pacheco, C.; Balaam, M.; Ahmadpour, N.; Loke, L. Body Maps: A Generative Tool for Soma-Based Design. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction; ACM: Daejeon Republic of Korea, February 13, 2022; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, L.R. Contemplative Pedagogy: Creating Mindful Educators and Classrooms. Perspect ASHA SIGs 2021, 6, 1540–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltz, J.; Kersten-Parrish, S. Using Children’s Picturebooks to Facilitate Restorative Justice Discussion. The Reading Teacher 2020, 73, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasso, N.A. How Is Exercise Different from Physical Activity? A Concept Analysis: DASSO. Nurs Forum 2019, 54, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, P. Reading for the Plot: Design and Intention in Narrative; 7. print.; Harvard Univ. Press: Cambridge, Mass, 2002; ISBN 978-0-674-74892-7. [Google Scholar]

- Futerman, L. Mama Died (Messenger) 2021.

- Zhang, Z.; Nash, C.; Dort, B. Confirmation of Payment- CD049040 2019.

- Newton, N. Starting a Publishing House. RSA Journal 1989, 137, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T.A. Publish Your Own Magazine, Guidebook, or Weekly Newspaper: How to Start, Manage, and Profit from a Home-Based Publishing Company; Sentient Publications: Boulder, CO, 2004; ISBN 978-1-59181-003-2. [Google Scholar]

- Paskin, N. Digital Object Identifier (DOI®) System. In Understanding Information Retrieval Systems; Bates, M.J., Ed.; Auerbach Publications, 2011; pp. 625–634 ISBN 978-0-429-18510-6.

- Ford, D. How to Start and Run a Small Book Publishing Company: A Small Business Guide to Self-Publishing and Independent Publishing. Technical Communication 2004, 51, 440–441. [Google Scholar]

- French, J.; Curd, E. Zining as Artful Method: Facilitating Zines as Participatory Action Research within Art Museums. Action Research 2022, 20, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Cantillon, Z. Zines as Community Archive. Arch Sci 2022, 22, 539–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.; Bennett, A. The Felt Value of Reading Zines. Am J Cult Sociol 2021, 9, 115–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, A. A Citation Analysis about Scholarship on Zines. Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Date |

|---|---|

| 1 | Sunday 15 November 2015 |

| 2 | Wednesday 18 November 2015 |

| 3 | Wednesday 9 December 2015 |

| 4 | January 2016-June 2016 |

| 5 | June 2016-August 2019 |

| 6 | 19-29 September 2016/ 30 September – 19 October 2016 |

| # | Location |

|---|---|

| 1 | 26 St. Joseph Street. Apt. 603., Toronto |

| 2 | Upper Library, Massey College, 4 Devonshire Place, Toronto |

| 3 | 26 St. Joseph Street. Apt. 603., Toronto |

| 4 | 26 St. Joseph Street. Apt. 603., Toronto |

| 5 | Internet |

| 6 | C J Graphics, 134 Park Lawn Rd. Toronto /Tampold Publishing parent company, 87 Avenue Rd., Toronto / Caversham Booksellers, 98 Harbord St., Toronto |

| # | Who Was Involved |

|---|---|

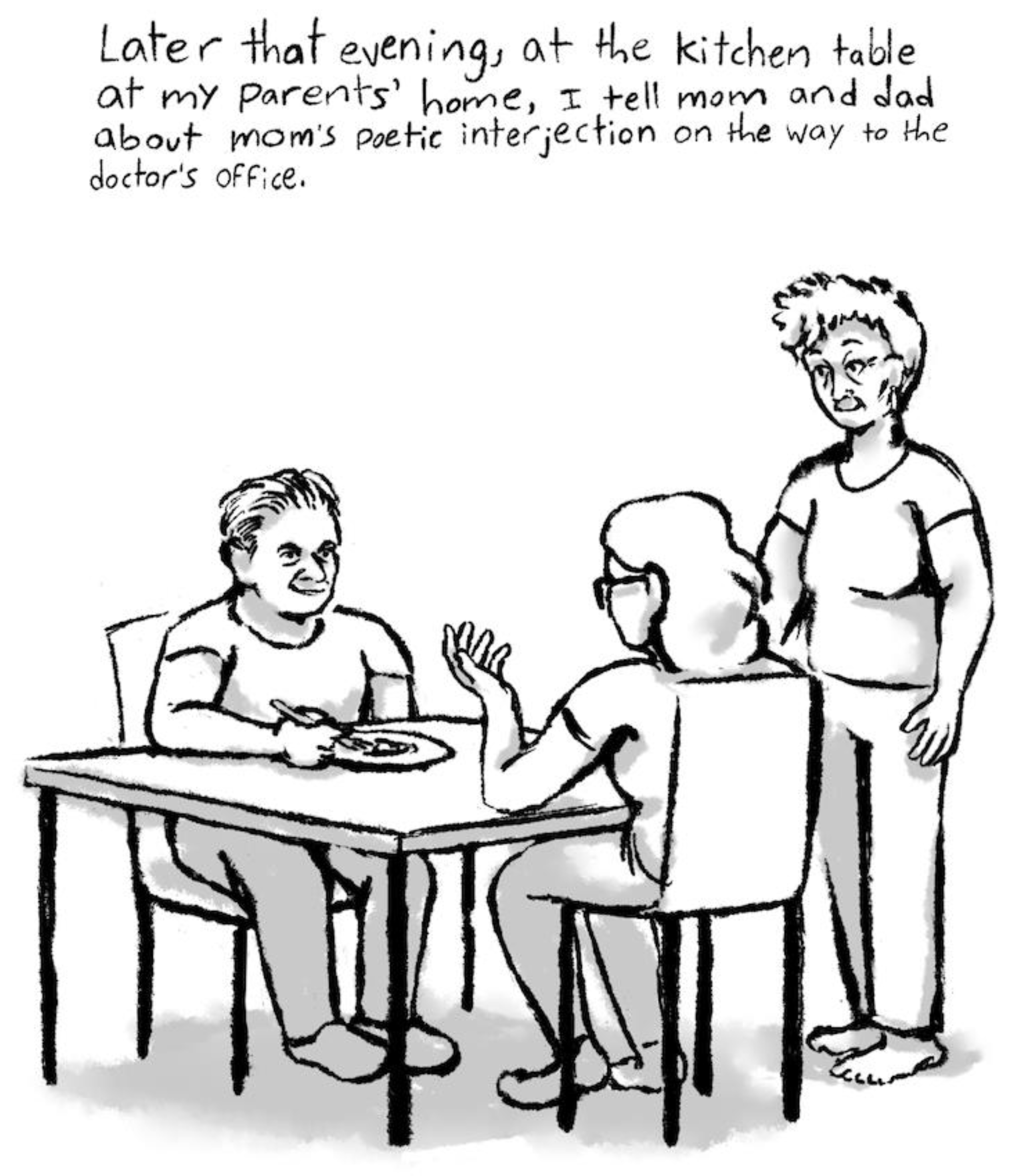

| 1 | Sarah Leavitt, rereading Tangles: A Story About Alzheimer’s, My Mother and Me |

| 2 | Liza Futerman, Evi Tampold, Carol Nash PnD, Mike Green MD |

| 3 | Liza Futerman, Evi Tampold, Carol Nash |

| 4 | Liza Futerman, Evi Tampold |

| 5 | Liza Futerman, Evi Tampold, Carol Nash |

| 6 | Boris Medan/Brian Dort, CJ Graphics|Carol Nash/ Joe Adelaars. Caversham Booksellers |

| # | What Was the Pivotal Point |

|---|---|

| 1 | Writing a testimony of ‘a day in a life’ |

| 2 | Discussing The Hallway Closet |

| 3 | Offer of collaboration |

| 4 | Expressing time as an empty signifier in the illustration |

| 5 | Changing expression on page 3 to not show anger/ errors found |

| 6 | Book is printing, delivered and transported to the bookstore |

| # | How it Happened |

|---|---|

| 1 | 4 or 5 hours of stream of consciousness or somatic writing |

| 2 | Attended the Comics and Healthcare Panel |

| 3 | Home cooked meal |

| 4 | After a long discussion about the philosophical implications of time |

| 5 | In discussion between author and illustrator / publisher and printer |

| 6 | Continuous email contact |

| # | Why it Happened |

|---|---|

| 1 | Express and communicate grief, gratitude, and joy at mother’s 60th birthday |

| 2 | Organized by Prof. Shelly Wall, (Illustrator In Residence, Faculty of Medicine) |

| 3 | fan graphic medicine memoirs / wanted to have story reach the most people possible |

| 4 | Combination of images and words required a powerful effect |

| 5 | Facial expression considered too harsh / errors and the requirements for printing |

| 6 | Advocate for culture change in dementia care by purchasing the book |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).