Submitted:

06 June 2024

Posted:

07 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Esteem: Conceptualization

1.2. Low Self-Esteem as a Risk Factor

1.3. Body Satisfaction: Conceptualization

1.4. Distorted Perception of Body Image

1.5. Body Dissatisfaction as a Risk Factor

1.6. Instagram and Its Impact on Body Image

1.7. Sociocultural Factors

1.8. Personal Factors

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Assessment Tools

- Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ): Developed by Cooper et al. [22] and adapted into Spanish by Raich et al. [60], this questionnaire measures dissatisfaction with body image, as well as concern about one's own image and self-perception. The BSQ consists of 34 items evaluated on a 6-category ordinal scale (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Very Often, Always). It assesses body image satisfaction and dissatisfaction, the frequency and type of thoughts about physical appearance, social comparisons, feelings about one's own physique, and compensatory behaviors to regulate anxiety generated by body image dissatisfaction. The BSQ scores are obtained by summing the total scores, with a minimum of 34 points (high body satisfaction) and a maximum of 204 points (high body dissatisfaction). Neither Cooper et al. [22] nor other researchers establish universal benchmarks; thus, this study established the following categorical ranges: high satisfaction (34-76), moderate satisfaction (77-119), low satisfaction (120-160), and very low satisfaction (161-204).

- Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Developed by Rosenberg [11] and adapted into Spanish by Atienza et al. [61], this scale measures the subjective evaluation of one's own self-esteem in terms of self-respect and self-worth. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale has 10 items evaluated on a 4-category ordinal scale (Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Agree, Strongly Agree). It assesses thoughts, beliefs, and feelings about one's abilities, value, and competence. The results are interpreted considering the following categorical groups: low self-esteem (10-15), medium-low self-esteem (16-21), medium self-esteem (22-27), high self-esteem (28-33), and very high self-esteem (34-40).

- Single-Item Self-Esteem Scale: Developed by Trzesniewski [62] and translated into Spanish for this study, this scale measures the overall perceived level of self-esteem of the individual. The Single-Item Self-Esteem Scale consists of one item: "I have high self-esteem in general," evaluated on a Likert scale with numerical categories from 1 to 7, where 1 is "Not very true of me" and 7 is "Very true of me." This scale does not have specific cutoff points as it is a subjective and simplified assessment of self-esteem. Therefore, the results are interpreted according to numerical categories: intervals from 1-3 approximately relate to low self-esteem perception, interval 3-4 to moderate self-esteem, and interval 5-7 to high self-esteem.

- Ad Hoc Interest Questions: These questions were developed to complement the necessary information for the study. The selected questions gather information about physical comparison behaviors, the impact of Instagram on self-esteem and satisfaction, concern about one's image and figure, concern about musculature, the influence of sociocultural factors on satisfaction and self-esteem, and cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects related to body image, among other issues.

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Explanatory Factors Associated with Self-Esteem and Body Satisfaction

3.3. Results Related to Body Satisfaction of the Sample

3.4. Relationship between Instagram Use and Body Satisfaction of the Sample

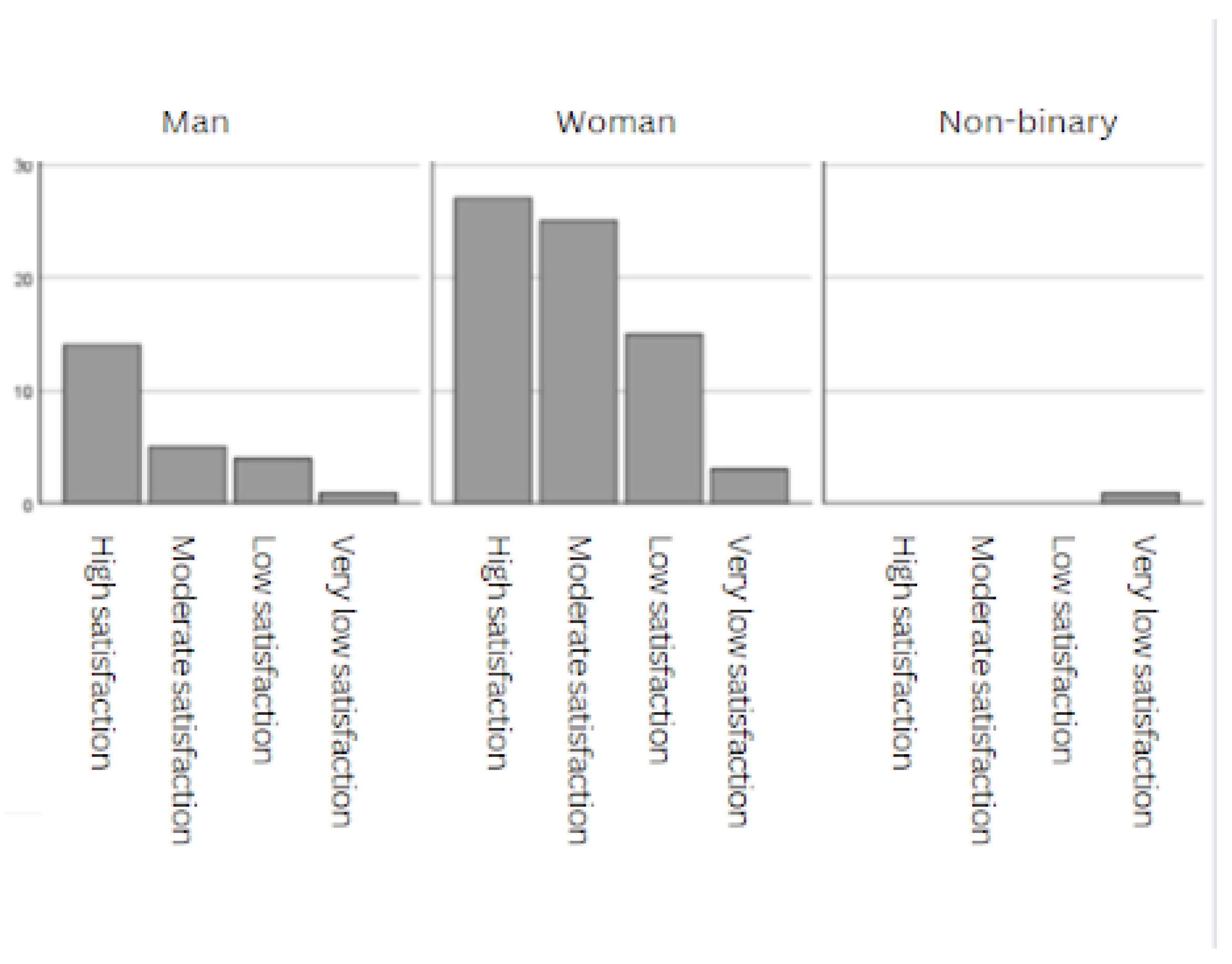

3.5. Relationship between Gender and Body Satisfaction of the Sample

3.6. Results Related to Self-Esteem of the Sample

3.7. Relationship between Instagram Use and Self-Esteem of the Sample

3.8. Relationship between Body Satisfaction and Self-Esteem of the Sample

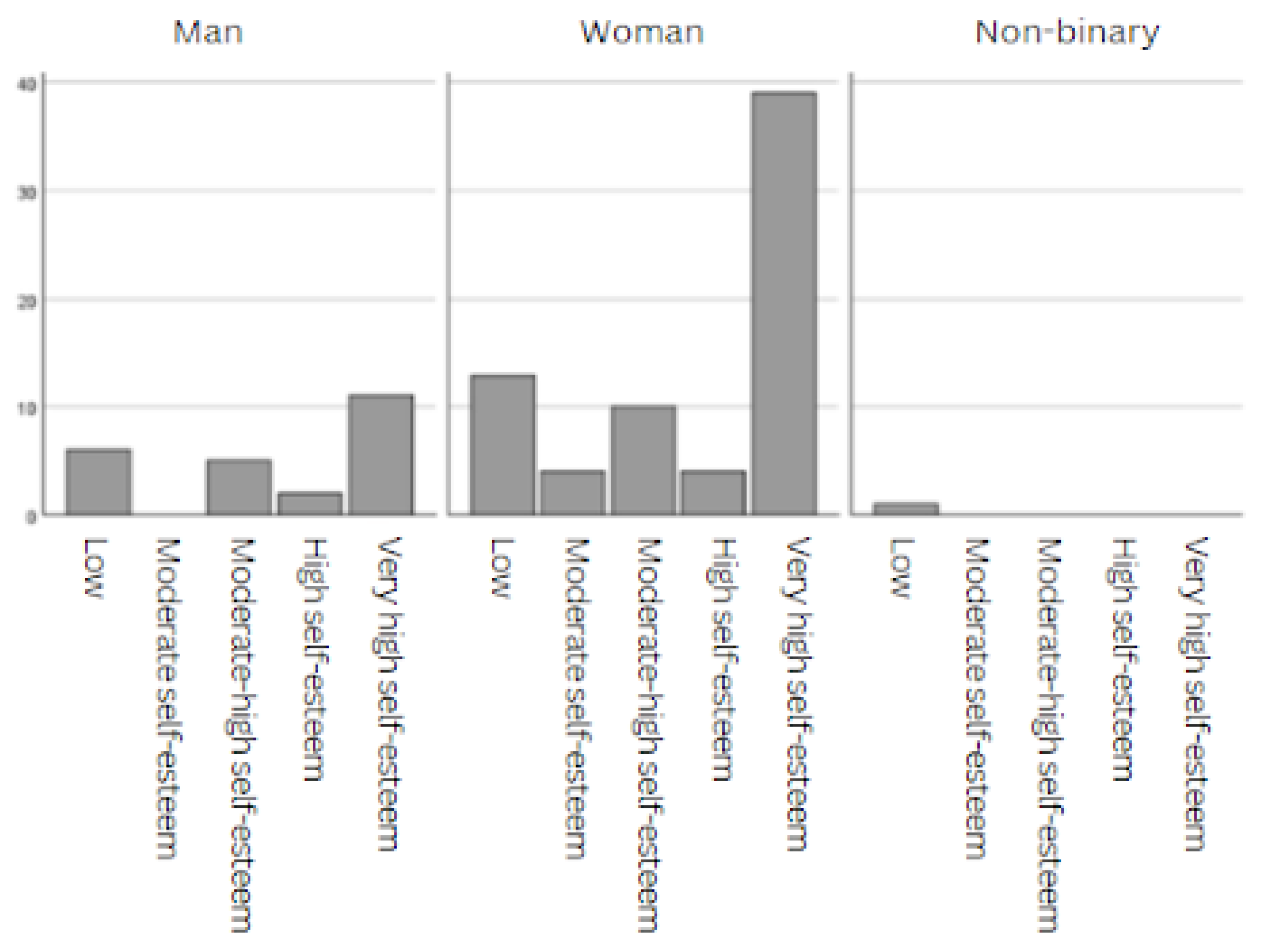

3.9. Relationship between Gender and Self-Esteem of the Sample

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Prospective Directions

- Expand and Balance the Sample: Increase the sample size and ensure gender balance to allow for the application of more robust and representative statistical tests.

- Utilize Updated Instruments: Employ a variety of contemporary instruments to detect social desirability and body dysmorphia, in addition to collecting detailed data on Instagram usage and its impact on users.

- Conduct Longitudinal Studies: Implement a longitudinal study design to examine changes over time in Instagram usage and its effects on self-esteem and body satisfaction.

- Include Control and Experimental Groups: Consider the inclusion of control and experimental groups, and stratify the analysis by gender and age ranges.

- Investigate the Impact on Eating and Dysmorphic Disorders: Explore the impact of Instagram on eating disorders and body dysmorphic disorders, given the links between these disorders and self-esteem.

- Develop Intervention Programs: Create intervention programs aimed at addressing issues of low self-esteem, body dissatisfaction, and social media addiction to mitigate the associated distress.

5. Conclusions

- Instagram Use and Body Satisfaction: The number of hours that users in the sample spend on Instagram correlates significantly with the level of body dissatisfaction they experience.

- Instagram Use and Self-Esteem: There was insufficient evidence in the data to deter-mine that the number of hours users spend on Instagram negatively affects their level of self-esteem.

- Self-Esteem and Body Satisfaction: Users in the sample with higher self-esteem tended to exhibit higher levels of body satisfaction. Conversely, those with lower self-esteem showed greater levels of body dissatisfaction.

- Gender Influence: Gender was not found to be an influential variable on the self-esteem and body satisfaction of the participants. However, it is important to con-duct further studies to deeply analyze the influence of gender, considering the sample size limitations of this study.

- Research Design Recommendations: Future studies should consider the following de-sign characteristics:

- Include larger sample sizes to enhance the power and representativeness of the findings.

- Aim for a balanced gender representation in the sample.

- Use a varied number of standardized instruments to ensure reliability and validity.

- Include a control group (non-Instagram users) and an experimental group (Instagram users).

- Develop intervention programs addressing issues of self-esteem and body satisfaction.

- Investigate the impact of Instagram on the development of eating disorders (EDs) and body dysmorphic disorders.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scully, M.; Swords, L.; Nixon, E. Social comparisons on social media: online appearance-related activity and body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2023, 40, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarman, H.K.; A McLean, S.; Slater, A.; Marques, M.D.; Paxton, S.J. Direct and indirect relationships between social media use and body satisfaction: A prospective study among adolescent boys and girls. New Media Soc. 2021, 26, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryding, F.C.; Kuss, D.J. The use of social networking sites, body image dissatisfaction, and body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review of psychological research. Psychol. Popul. Media 2020, 9, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, M.; Soomro, S.A.; Ahmad, N. Impact of Social Media on Self-Esteem. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2017, 13, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maymone, M.B.C.; Neamah, H.H.; Secemsky, E.A.; Kundu, R.V.; Saade, D.; Vashi, N.A. The Most Beautiful People: Evolving Standards of Beauty. JAMA Dermatol. 2017, 153, 1327–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmsee, I.-S.O.; Hank, P.; Bosnjak, M. Low Self-Esteem as a Risk Factor for Eating Disorders. Z. Fur Psychol. Psychol. 2021, 229, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieiro, P.; González-Rodríguez, R.; Domínguez-Alonso, J. Self-esteem and socialisation in social networks as determinants in adolescents' eating disorders. Heal. Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, E4416–E4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, L.; Zeman, J. The Contribution of Emotion Regulation to Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating in Early Adolescent Girls. J. Youth Adolesc. 2006, 35, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Mozaffari, H.; Askari, M.; Azadbakht, L. Association between overweight/obesity with depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and body dissatisfaction in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 62, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçınkaya-Alkar, Ö. Is self esteem mediating the relationship between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depression? Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Journal of Religion and Health, 21(4), 139-153.

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2016). Introduction to the Psychology of Self-Esteem. In F. Holloway (Ed.), Self-Esteem (p. 1). Nova Science Publishers, Inc. ISBN: 978-1-53610-294-9.

- Branden, N. (2021). The power of self-esteem. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications, Inc.

- Casale, S. (2020). Gender Differences in Self-esteem and Self-confidence. In The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences: Personality Processes and Individual Differences (pp. 185-189). [CrossRef]

- Josephs, R.A.; Markus, H.R.; Tafarodi, R.W. Gender and self-esteem. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Fioravanti, G.; Benucci, S.B.; Falone, A.; Ricca, V.; Rotella, F. A meta-analysis on the association between self-esteem and problematic smartphone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 134, 107302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, M.; Li, S.; Yang, Y. Social support, resilience, and self-esteem protect against common mental health problems in early adolescence: A non-recursive analysis from a two-year longitudinal study. Medicine 2021, 100, e24334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Wright, E.P.; Dedding, C.; Pham, T.T.; Bunders, J. Low Self-Esteem and Its Association With Anxiety, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation in Vietnamese Secondary School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.R.; Jayappa, R.; James, M.; Kulnu, A.; Kovayil, R.; Joseph, B. Do Low Self-Esteem and High Stress Lead to Burnout Among Health-Care Workers? Evidence From a Tertiary Hospital in Bangalore, India. Saf. Health Work. 2020, 11, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M. (2011). Sociocultural perspectives on human appearance and body image. In T. F. Cash & L. Smolak (Eds.), Body image: A handbook of science, practice, and prevention (pp. 12–19). The Guilford Press.

- Taylor, M. J. (1987). The nature and significance of body image disturbance (Doctoral dissertation, University of Cambridge).

- Cooper, P. J. , Taylor, M. J., Cooper, Z., & Fairburn, C. G. (1987). Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ). Retrieved from: https://www.uv.es/lisis/instrumentos/forma-corporal.

- Fischetti, F.; Latino, F.; Cataldi, S.; Greco, G. Gender differences in body image dissatisfaction: The role of physical education and sport. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2020, 15, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baile, J. I. (2005). Vigorexia: Cómo reconocerla y evitarla. Síntesis.

- Marques, M.D.; Paxton, S.J.; McLean, S.A.; Jarman, H.K.; Sibley, C.G. A prospective examination of relationships between social media use and body dissatisfaction in a representative sample of adults. Body Image 2022, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiphoo, A.N.; Vahedi, Z. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between social media use and body image disturbance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, M.R.; Grieve, F.G. Body image dissatisfaction, social physique anxiety, and eating behaviors in female exercisers. Body Image 2020, 36, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F. y Pruzinsky, T. (1990). Body images: development, deviance and changes. Nueva York. Guilford Press. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S. A. , & Padhy, R. K. (2019). Body image distortion.

- Ben Ayed, H.; Yaich, S.; Ben Jemaa, M.; Ben Hmida, M.; Trigui, M.; Jedidi, J.; Sboui, I.; Karray, R.; Feki, H.; Mejdoub, Y.; et al. What are the correlates of body image distortion and dissatisfaction among school-adolescents? Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Heal. 2019, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaberria, K. , Rodríguez, S., & Cruz, S. (2007). Percepción de la imagen corporal. Osasunaz, 8(2), 171-183.

- Gardner, R. M. (2011). Perceptual measures of body image for adolescents and adults. In T. F. Cash & L. Smolak (Eds.), Body image: A handbook of science, practice, and prevention (2nd ed., pp. 146–153). The Guilford Press.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). [CrossRef]

- Parillo Pérez, P. , & Troncoso Quispe, M. G. (2019). Influencia de la red social Instagram en la percepción de la imagen corporal en adolescentes.

- Collison, J.; Harrison, L. Prevalence of Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Predictors of Body Image Disturbance in Adolescence. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchôa, F.N.M.; Uchôa, N.M.; Daniele, T.M.d.C.; Lustosa, R.P.; Garrido, N.D.; Deana, N.F.; Aranha. C.M.; Alves, N. Influence of the Mass Media and Body Dissatisfaction on the Risk in Adolescents of Developing Eating Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, K.A.; Heron, K.E.; Henson, J.M. Examining associations among weight stigma, weight bias internalization, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms: Does weight status matter? Body Image 2021, 37, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, E.; Chow, C.M. “I just don’t want to be fat!”: body talk, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms in mother–adolescent girl dyads. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2020, 25, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skemp, K.M.; Elwood, R.L.; Reineke, D.M. Adolescent Boys are at Risk for Body Image Dissatisfaction and Muscle Dysmorphia. Californian J. Heal. Promot. 2019, 17, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martenstyn, J.A.; Maguire, S.; Griffiths, S. A qualitative investigation of the phenomenology of muscle dysmorphia: Part 1. Body Image 2022, 43, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounsefell, K.; Gibson, S.; McLean, S.; Blair, M.; Molenaar, A.; Brennan, L.; Truby, H.; McCaffrey, T.A. Social media, body image and food choices in healthy young adults: A mixed methods systematic review. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, I.; De Luca, I.; Giorgetti, V.; Cicconcelli, D.; Bersani, F.S.; Imperatori, C.; Abdi, S.; Negri, A.; Esposito, G.; Corazza, O. Fitspiration on social media: Body-image and other psychopathological risks among young adults. A narrative review. Emerg. Trends Drugs, Addict. Heal. 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, J.J.; Tng, G.Y.Q.; Yang, S. Effects of Social Media and Smartphone Use on Body Esteem in Female Adolescents: Testing a Cognitive and Affective Model. Children 2020, 7, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, B.; Zaki, M.; Javaid, S.; Jabeen, Z.; Mehmood, M.; Riaz, M.; Maqbool, L.; Omar, H. Increase in body dysmorphia and eating disorders among adolescents due to social media: Increase In Body Dysmorphia and Eating Disorders Among Adolescents. Pak. Biomed. J. 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, L.M.; Iorga, M.; Iurcov, R. Body-Esteem, Self-Esteem and Loneliness among Social Media Young Users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, A.T.; Jarman, H.K.; Doley, J.R.; McLean, S.A. Social Media Use and Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescents: The Moderating Role of Thin- and Muscular-Ideal Internalisation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 13222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, A.; Khanjani, S.; Asl, E.M. Relationship of Concern About Body Dysmorphia with External Shame, Perfectionism, and Negative Affect: The Mediating Role of Self-Compassion. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.K.; Heinberg, L.J.; Altabe, M.; Tantleff-Dunn, S. Exacting beauty: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment of Body Image Disturbance; American Psychological Association (APA): Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann, M. (2012). Sociocultural perspectives on body image. In T. F. Cash (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Body Image and Human Appearance (Vol. 2, pp. 758-765). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- García Fernández, J. L. (2020). Tus hijos ven porno. ¿Qué vas a hacer? Amazon.

- Chang, L.; Li, P.; Loh, R.S.M.; Chua, T.H.H. A study of Singapore adolescent girls’ selfie practices, peer appearance comparisons, and body esteem on Instagram. Body Image 2019, 29, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.S.; Robson, D.A. Personality and body dissatisfaction: An updated systematic review with meta-analysis. Body Image 2020, 33, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tort-Nasarre, G.; Pocallet, M.P.; Artigues-Barberà, E. The Meaning and Factors That Influence the Concept of Body Image: Systematic Review and Meta-Ethnography from the Perspectives of Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollatos, O.; Georgiou, E.; Kobel, S.; Schreiber, A.; Dreyhaupt, J.; Steinacker, J.M. Trait-Based Emotional Intelligence, Body Image Dissatisfaction, and HRQoL in Children. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, L.A.; Kracht, C.L.; Denstel, K.D.; Stewart, T.M.; Staiano, A.E. Bullying experiences, body esteem, body dissatisfaction, and the moderating role of weight status among adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2021, 91, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quittkat, H.L.; Hartmann, A.S.; Düsing, R.; Buhlmann, U.; Vocks, S. Body Dissatisfaction, Importance of Appearance, and Body Appreciation in Men and Women Over the Lifespan. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischetti, F.; Latino, F.; Cataldi, S.; Greco, G. Gender differences in body image dissatisfaction: The role of physical education and sport. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2020, 15, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M.; Hayden, S.; Brown, Z.; Veldhuis, J. The effect of Instagram “likes” on women’s social comparison and body dissatisfaction. Body Image 2018, 26, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, I. , & León, O. G. (2002). Clasificación y descripción de las metodologías de investigación en Psicología. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 2(3), 503-508. Retrieved from: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=33720308.

- Raich, R. M. (1996). Body image: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. Guilford Press: New York, USA.

- Atienza, F. L. , Balaguer, I., & Moreno, Y. (2000). Análisis de la satisfacción corporal en adolescentes españoles. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 9(1), 45-56.

- Trześniewski, K. H. (2001). Single-Item Self Esteem Scale.

- Ryding, F.C.; Kuss, D.J. The use of social networking sites, body image dissatisfaction, and body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review of psychological research. Psychol. Popul. Media 2020, 9, 412–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T. F. , & Smolak, L. (2011). Body Image: A Handbook of Science, Practice, and Prevention (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Marques, M.D.; Paxton, S.J.; McLean, S.A.; Jarman, H.K.; Sibley, C.G. A prospective examination of relationships between social media use and body dissatisfaction in a representative sample of adults. Body Image 2022, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.B.; Haynos, A.F.; Wall, M.M.; Chen, C.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Fifteen-Year Prevalence, Trajectories, and Predictors of Body Dissatisfaction From Adolescence to Middle Adulthood. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 1403–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.A.; Orth, U. The link between self-esteem and social relationships: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 119, 1459–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarman, H.K.; A McLean, S.; Slater, A.; Marques, M.D.; Paxton, S.J. Direct and indirect relationships between social media use and body satisfaction: A prospective study among adolescent boys and girls. New Media Soc. 2021, 26, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Pecino, R.; Garcia-Gavilán, M. Likes and Problematic Instagram Use: The Moderating Role of Self-Esteem. Cyberpsychology, Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Lennon, S.J. Mass Media and Self-Esteem, Body Image, and Eating Disorder Tendencies. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2007, 25, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Educational level Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO) High School Diploma Vocational training (FP) University Degree Postgraduate/Master's Degree Doctorate/PhD Competitive Exam Candidate |

1 4 13 33 33 2 9 |

1.1% 4.2% 13.7% 34.7% 34.7% 2.1% 9.5% |

|

Nationality Spain France Brazil Peru Germany |

89 1 2 2 1 |

93,7% 1.1% 2.1% 2.1% 1.1% |

|

Residence location Extremadura Comunidad Valenciana Madrid Salamanca Sevilla Málaga Others |

38 25 13 7 4 3 5 |

39.47% 26.32% 13.68% 7.37% 4.21% 3.16% 5.26% |

|

Profession Student Psychologist Teacher / Professor Social Worker Veterinarian Translator Others |

36 12 9 2 3 2 31 |

37.89% 12.63% 9.47% 2.11% 3.16% 2.11% 32.63% |

|

History of ED No Yes |

89 6 |

93.70% 6.30% |

|

Frequency of comparison Generally, I don't do it Frequently Sometimes |

54 13 28 |

56.8% 13.7% 29.5% |

|

Time spent thinking about defects >1 hour <1 hour |

15 80 |

15.8% 84.2% |

|

Purpose of Instagram Account Leisure Personal Business Other |

45 40 7 3 |

47.4% 42.1% 7.4% 3.2% |

|

Modifications in appearance or lifestyle Yes No From time to time |

13 57 25 |

13.7% 60% 26.3% |

| Self-esteem | Body satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Test and significance level | |

| Profession | H = 17.88 p = .007* |

|

| History of ED | U = 135.50 p = .028* |

U = 106.50 p = .009* |

| Frequency of comparison | H = 22.09 p < .001* |

H = 17.69 p < .001* |

| Time Spent Thinking about Defects | U = 179.00 p < .001* |

U = 224.50 p < .001* |

| Body Satisfaction Category | Score range | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Satisfaction | 34 - 76 | 41 | 43.2% |

| Moderate Satisfaction | 77 - 119 | 30 | 31.6% |

| Low Satisfaction | 120 - 160 | 19 | 20.0% |

| Very Low Satisfaction | 161 - 204 | 5 | 5.3% |

| Self-Esteem Category | Score range | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Self-Esteem | 10 - 15 | 20 | 21.1% |

| Medium-Low Self-Esteem | 16 - 21 | 4 | 4.1% |

| Medium Self-Esteem | 22 - 27 | 15 | 15.8% |

| High Self-Esteem | 28 - 33 | 6 | 6.3% |

| Very High Self-Esteem | 34 - 40 | 50 | 52.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).