1. Introduction

Historic districts are invaluable resources as unique areas of the city that serve multiple functions and harbor cultural memories. The governance of historic districts has long been a significant social issue [

1]. As China’s urban development and construction shifted from an era dominated by increment (1988 to 2014) to an era of high-quality, people-centred development [

2], urban regeneration is increasingly seen as a crucial means to achieve high-quality development [

3,

4]. As an integral part of cities, the regeneration of historic communities has become a key issue in China's current urban development.

However, the renewal of historic districts in China has long been in a dilemma. When the regeneration of a historic area fails to generate sufficient market revenue, especially in cities with an underdeveloped tourism economy, it tends to be ‘frozen in conservation’ [

5] and become relics threatened by degradation. When the renovation of a historic environment is successful in the market, the regeneration mode may be quickly replicated in completely different places, sometimes even in large-scale ‘demolition-reconstruction’. In addition, the urban regeneration of the historic environment in China follows the logic of capital recycling centered on economic profits, while it is also seen as a governance means to alleviate urban decline, solve social problems, and maintain social harmony and diversity.

Because of the complexity of the regeneration of the historic environment, the traditional single logic of ‘heritage preservation’ and ‘economic development’ can no longer promote long-term development [

4]. There is a need for an integrated sustainable perspective to guide future regeneration efforts.

This research is motivated by the successful regeneration of Taiyuan's Bell Tower Street. Taiyuan, a lower-tier second-level city in China with a per capita GDP of $11,000 in 2022, has an underdeveloped tertiary and tourism economy. Since 2014, the city has planned to regenerate its historic Bell Tower Street. Despite initial difficulties with developers who found potential losses in the project, the municipality adopted a public value-oriented approach. Completed in 2021, the regeneration received positive feedback from various sectors. Therefore, this leads to the key two questions this research purses to address:

To answer these questions, this research aims to propose a novel analytical framework for the regeneration of historic districts. This research integrates secondary and primary sources, combing literature review and semi-structured interviews to provide a comprehensive analysis. This article focuses on analyzing the regeneration case of Taiyuan Bell Tower Street, applying our proposed framework to understand the reasons behind the project's success, and exploring how spatial form and urban governance strategies have contributed to creating public value in the revitalization.

The reminder of this article is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a exhaustive literature review of relevant studies and key concepts. In

Section 3 and

Section 4 we established a framework of historic regenerations from the perspective of spatial form and urban governance respectively.

Section 5 illustrates the Taiyuan Bell Tower Street renewal project and analyzes the impact of spatial morphological and urban governance on public value. The final part of this paper provides a discussion and offers practical suggestions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Public Value

Since the early 1990s, values-based approaches to historic environment conservation have increasingly dominated discussions in academic and professional circles [

6,

7]. Although the concept ‘public value’ was originally introduced by Harvard University Public Management professor Mark H. Moore in 1995, and it has been well implemented in Cerda's theory of urbanization in 1867 [

8]. Public value refers to the benefit or worth that a government or public organization creates for society [

9,

10]. The historic environment, as heritage, the essence of what people cherish and aspire to pass on to the future, is a crucial element of the public realm [

11]. The concept of public value supplies a new way to measure the performance of a historic environment that is open to the public.

The challenge lies in discovering a valuation model that effectively integrates the precision of conventional economically derived methods with the less exact values-based approach, providing meaningful and valuable insights, as they state, ‘those things that were easy to measure tended to become objectives and those that count was downplayed or ignored’ [

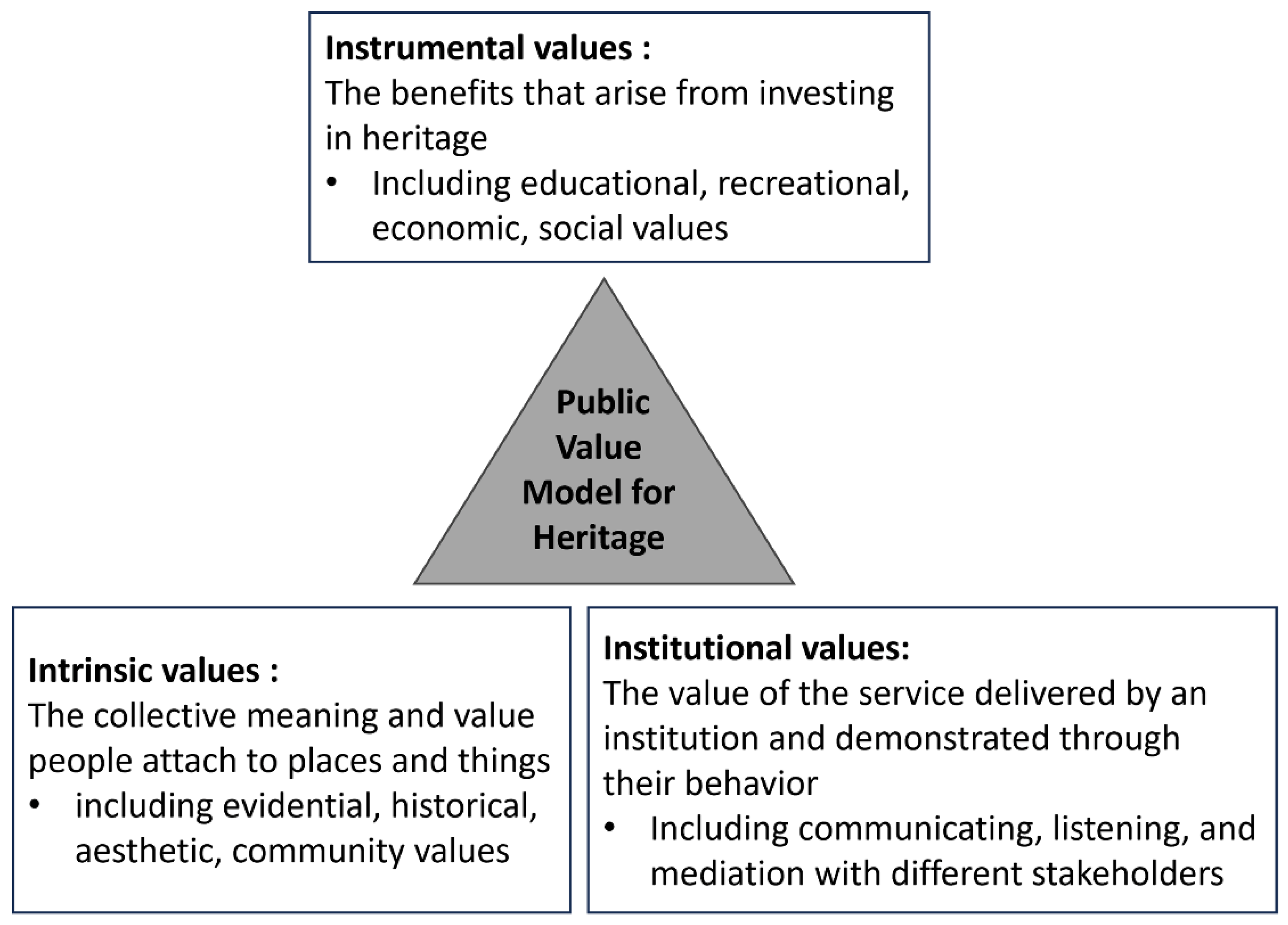

11](p2). Robert Hewison and John Holden (2011) proposed a public value model for heritage based on Moore's theory (

Figure 1). It was adopted by the UK Heritage and Heritage Lottery Fund and it represents a shift from a traditional fabric-based toward a public value-based approach in UK Heritage practice. In addition, The Accenture Public Service Value Model evaluates optimize user experience (including visitor numbers and quality of user experience), optimize impact on local community (including economic, social, education) and optimize benefit to wider population (macroeconomic). This process, originating from traditional commercial principles like 'shareholder value,' the model reorients its focus towards citizens, treating them as the primary investors and key stakeholders [

11](p20).

However, although in the field of public management, measuring public value has entered its maturity phase [

12], it is still a rough model that needs to be refined when applied in the field of urban planning.

2.2. Spatial Form

Spatial form refers to the physical and built environment in which public life occurs, including buildings, streets, parks, and other public spaces. It is the ‘objectivation of the spirit’ of the succession of societies that inhabit it [

13](pp.57-61) and it similarly reflects society's values about the historic environment. The design and organization of these spaces can have a significant impact on the social and cultural life of communities, and on the degree to which they foster a sense of publicness -that is, a shared sense of identity, belonging, and collective action. Based on geography represented by Conzen and architecture represented by Caniggia, Sadeghi argues that a systematic interpretation of the forms and types of man-made urban fabric developed over time and combined with social change can provide a good understanding of the present society and the potential needs for future development [

14]. Spatial form explains to some extent the logic of urban functioning and that it interacts with social conditions to shape public life [

15]. This makes the old city an engine of communication and creates value.

2.3. Urban Governance

Urban governance originates from ‘spatial governance’, which in turn originates from the definition of ‘spatial turn’ in social science, where space is both a product of social relations and a producer of social relations [

16]. The relationship between space and governance is interdependent and mutually reinforcing. Space shapes governance and governance reconstructs space. Generally, urban governance solves multidimensional problems caused by uneven distribution of benefits in the spatial production process by coordinating the allocators and methods of urban spatial ownership [

17]. Urban governance is an important part of modernizing the national governance system and governance capacity, and it is the improvement and innovation of urban management [

5].

At present, China is in the period of building urban governance system and governance capacity. The high-level development of urban governance must adhere to the value concept of "putting the people at the center" and respond to the issue of how to build people's cities.

3. Spatial Dimension: Spatial form Transformation Has a Creative Role in Historical Regeneration

From value-based perspective, in the regeneration of historic environment, the transformation of spatial forms at different scales creates different values [

18].

At the macro (urban) scale, numerous studies have demonstrated that reviving declining historic districts can lead to significant structural improvements and economic value for cities, contributing instrumental benefits. Since the 1990s in China, historic districts, previously integral to space production, have frequently been transformed into ‘scenic consumption zones’ under entrepreneurial government operations [

19]. In recent years, with the recognition of cultural capital, municipalities across the region have come to see the historic environment as a store of value, as well as a long-term asset that generates a stream of services over time and a catalyst for driving cultural tourism. Nocca, F. [

20], in analysis of 40 culture-driven regeneration cases, develops an evaluation framework showcasing the multifaceted advantages. This framework emphasizes that conserving cultural heritage is an investment rather than a financial burden on the city.

At the meso (street) scale, a high-quality urban space can facilitate public life, foster community, and provide opportunities for people to gather, interact, and participate in various activities, thereby creating social value. Sociability is the fundamental factor of vitality and the main goal of urban design is to enhance the sociability of urban space by building public spaces that better civic life [

21]. Recent studies have increasingly concentrated on utilizing the concept of ‘publicness’ to evaluate the characteristics and qualities of spaces that are publicly accessible and encourage social interaction and engagement among its residents and visitors from the perspective of urban spatial form [

22]. Conzen focused morphological identification of urban public space on the land use, street patterns, plot patterns, and building structure [

23]. Measuring publicness in urban morphology involves assessing the spatial characteristics and distribution patterns of public spaces and activities [

24]. Additionally, Jian, I. Y. et al [

25] have investigated how public open spaces are distributed and whether they are appropriately accessible to people from the perspective of physical justice. In addition to the social value created by spatial publicness, the historical value of the urban fabric within a historic environment is a consensus within the field of urban planning.

At the micro (plot & building) scale, the conservation, restoration, and utilization methods applied to buildings directly relate to the historical value, aesthetic value, and use value of historic districts. Therefore, assessing the current condition and value of the buildings in the historic environment and developing categorized protective renovation measures are necessary approaches. Due to the different durations between Chinese wooden and Western stone architecture, different from principles of authenticity with the West. The Eastern approach, unlike the Western focus on preserving tangible material characteristics, emphasizes an intangible value rooted in the traditional concept of not strictly distinguishing between originals and replicas, allowing for the replacement of components and materials to maintain the integrity and continuity of traditional craftsmanship [

26]. After going through three stages of adhering to tradition, drawing from the West, and self-awareness, the principle of ‘repairing the age as aged’ has been inherited as the fundamental principle in the preservation of Chinese architectural heritage [

27].

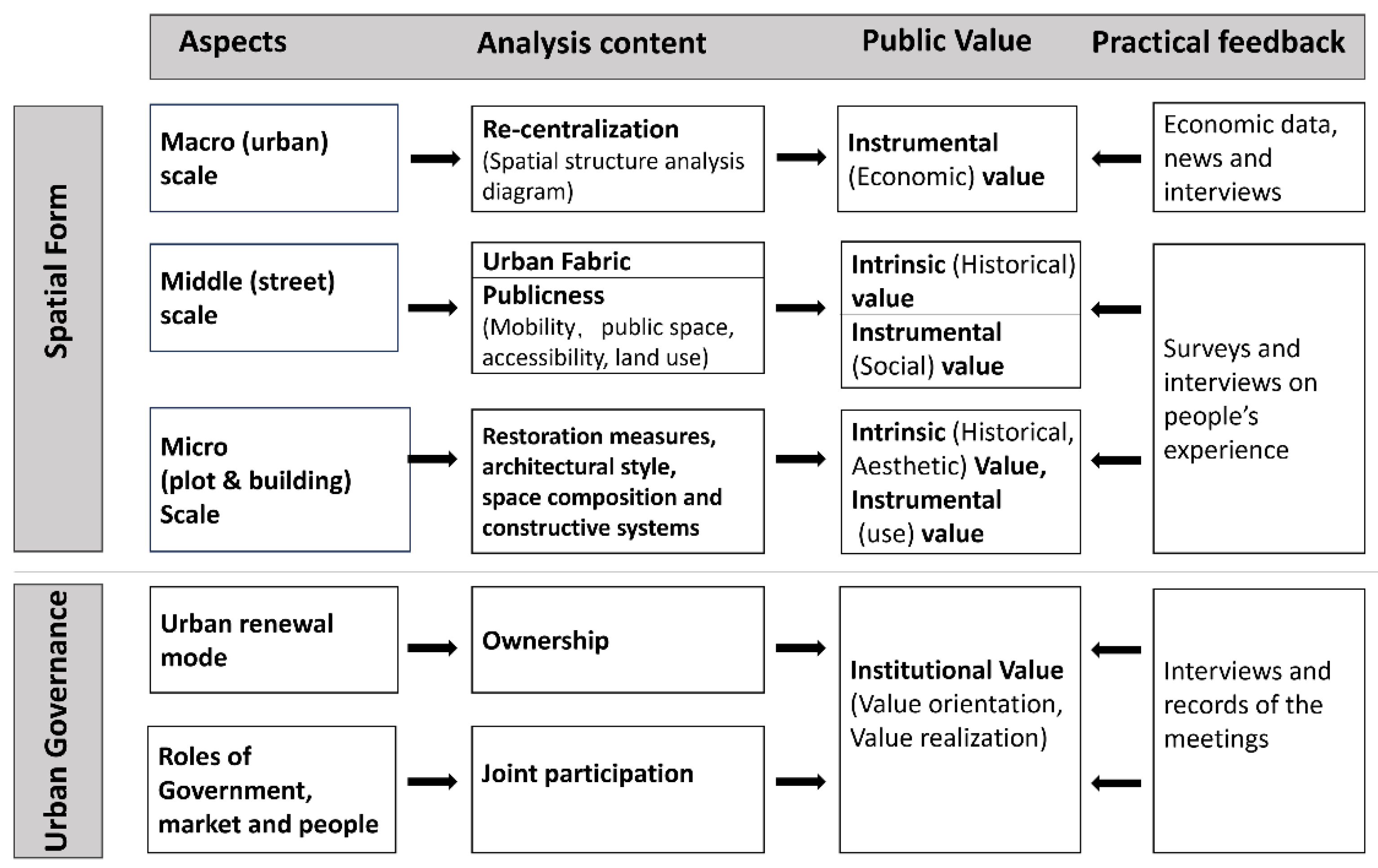

This study proposes an analytical framework that examines spatial form across three different scales (

Figure 2). On the macro (urban) scale, we consider the structural role of historical district revitalization, evaluating its economic value and structural function to the city through enhanced regional economy as practical feedback. On the meso (street) scale, we explore the historical and social value by examining the urban fabric and the publicness of spaces, with assessment on people's cultural and consumption experiences within the district. On the micro (plot & building) scale, historical, aesthetic, and use values within area regeneration are analyzed through restoration measures, architectural styles, space composition, and construction systems, which are based on people's experiences within these spaces.

4. Economic-Social Dimension: Public Value-Oriented Urban Governance Reinforces the Regeneration of the Historic Environment

In China, urban regeneration has been integrated as a mechanism for market development and capital accumulation. Given the centralized and profit-oriented decision-making process in China, cultural heritage management could easily become a top-down process in which local communities have insufficient opportunities to be engaged [

28,

29,

30]. From 1990s through the 2010s, government authorities primarily led the regeneration of historic environments. Urban planners devised corresponding plans for regeneration and preservation, which were then implemented and managed by developers after obtaining permits. However, the essence of these efforts largely revolved around profit-driven commercial real estate development. This often led to an excessive emphasis on economic gains, disregarding residents' preferences and leading to misunderstandings or even severe damage to the preservation of historical heritage [

31,

32].

Historic environment, with their aesthetic and heritage aspects, are recognized as public goods [

33]. Evaluating the publicness of their regeneration involves considering the ownership of the means of production [

34]. Researchers have thus developed their evaluation systems incorporating ownership, accessibility, and sociability as key criteria, emphasizing that ownership is crucial [

35]. Therefore, funding sources for the renovation of historic districts determine the value orientation of these environment.

In addition, public value management encourages the joint participation of multiple entities [

10]. The roles of government, market, and society determine whether public value can be realized through joint participation. In recent years, the Chinese urban regeneration management system has shown noticeable changes from a single subject to diverse subjects, from large-scale to micro-scale regeneration, and from top-down to collaborative governance [

36,

37,

38]. Urban planning turns from top-down management towards combining public policies with participative governance, a way of managing public affairs that mobilizes everyone's enthusiasm [

39]. For example, through analyzing the transformation role of government from management to governance in Shanghai Tian Zifang, He and Deng [

19] propose to encourage public participation in decision-making and to preserve the complexity and diversity of historical blocks. Furthermore, the government should act as the provider of public goods and sustainable development policies and ensure the continuation of community life in historic environment. When public rights are respected and their needs properly managed, regeneration projects in historic districts tend to proceed more smoothly [

40].

Our framework for analyzing urban governance is primarily considers urban regeneration mode and the roles of government, market, and people (

Figure 2). It is supported by a wealth of first-hand information collected from 2015 to 2021 during the author’s working experience at Taiyuan Urban & Rural Planning Design Institute, including minutes of the meetings of the project and semi-structured interviews with the Former Director of the Planning Bureau, Dean of Architectural Design Institute, and related planner and architect in charge.

5. Research on the Promotion Strategy of Historical Space Based on Spatial Form and Urban Governance-Taking Taiyuan Bell Tower Street as an Example

Taiyuan, the capital city of Shanxi Province with a rich history spanning over 2500 years, was acknowledged in 2011 by the Chinese State Council as a national historical and cultural city. Taiyuan Bell Tower (Zhonglou in Chinese) Street (

Figure 3), a historic environment (10.65 hectares), is located in the southern part of Taiyuan Old Town. It is a famous commercial street with great historical and cultural value dating back over 1,000 years since the construction of the city began in the Northern Song Dynasty in 982 AD (

Figure 4). Since the year 2000, the economic development of Bell Tower Street has been in a continuous decline, with serious damage to its historical features, disappearance of cultural characteristics, and intensifying social conflicts. After 2013, the city government planned to protect and renovate Bell Tower Street. After years of planning and discussion, the implementation of the protection and renovation project began in May 2020. The first phase of the project was completed in October 2021 and was opened to tourists.

5.1. Spatial Dimension: Spatial Morphological Changes at Different Scales and Their Contribution to Public Value Creation

5.1.1. At Macro (Urban) Scale

The landscape structure of Taiyuan can be described as ‘surrounded by three mountains in the west, north and east, with the Fen River flowing from north to south on the plain in the middle’. Taiyuan's main urban development axis also extends from north to south along the Fen River. Taiyuan Old Town was the center of the city in the 1990s, and after 2000, the center of the city gradually moved south. Bell Tower Street also gradually declined as a commercial street (

Figure 5).

In terms of spatial morphology, it can be seen (

Figure 6) that Bell Tower Street is located at the intertwined point of the historical and modern spatial structure of the Old Town. Bell Tower Street is located at the intersection of the north-south historical axis that goes through the Shanxi Fuya museum and the east-west historical axis that connects the Imperial Temple and Cong Yang Temple. The area is the center of civic activities defined by the three landmarks: the City God Temple, the Bell Tower and the Drum Tower. Meanwhile, Bell Tower Street is located in the middle of the urban development axis and the business axis, only 500 meters away from the Taiyuan Municipal Government. The regeneration of Bell Tower Street is an enhancement of the modern city center and a manifestation of the historical pattern of the old city.

From the effects of the regeneration, the Bell Tower Street area has reinstated the centrality it lost during the latter half of the 20th century. The daily foot traffic reaches between 30,000 to 60,000 people, surging to around 100,000 people during holidays(Source: News Office of Taiyuan Municipal People's Government ), significantly boosting the business revenues and tax income of traditional commercial environment like Liuxiang and the food street in Taiyuan (Ms. Feng, Researcher at the Taiyuan Municipal Development and Reform Commission). During the 2023 Mid-Autumn Festival and National Day holidays, the Bell Tower Street ranked as the fifth most popular street among 111 nationally recognized tourism and leisure districts across the country(Source: Shanxi Provincial Department of Culture and Tourism,). ‘Taiyuan has gradually transformed from being merely a tourist distribution center to a full-fledged tourist destination. The city of Taiyuan intends to further focus on Bell Tower Street as a pivotal point for the development of the urban cultural tourism industry, ‘said Ms. Feng. However, according to the shopkeepers, most people just come to visit, and take pictures but not consume. Due to the downturn background in the economy and the mismatch of commercial positioning, the businesses are operating at a low level. The huge foot traffic has brought about an increase of 30% in the business income of the neighboring shopping districts such as Food Street and Liuxiang Lane (Source: Dean of Design Institute). So, it is said that the operation of Bell Street itself is not profitable or even losing money, and its driving effect on the surrounding area exceeds the economic value of Bell Street itself.

5.1.2. On Meso (Street) Scale

Historical and social value can be measured in terms of urban fabric [

41], accessibility to different types of public spaces [

35], and mix of land use [

35,

42].

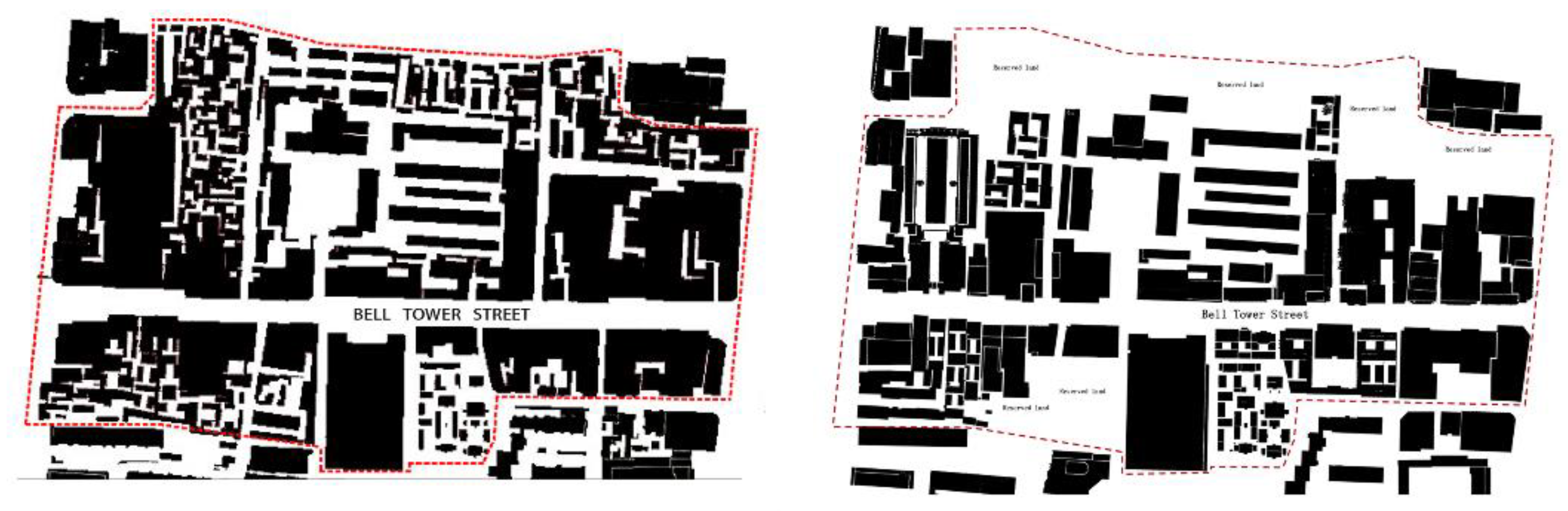

5.1.2.1. Urban Fabric (Figure 7).

The spatial texture representing historical value has been effectively preserved during the regeneration. The spatial arrangement, street layout, and overall size all maintain the distinctive features specific to Bell Tower Street. Within these familiar streets, visitors display dynamic scenes that blend a sense of familiarity with historical ambiance and modern-day life, showcasing the diverse and vibrant lifestyle of Bell Tower Street.

Figure 7.

The figures of urban fabric before (left) and after (right) regeneration (Source: self-drawn by the author).

Figure 7.

The figures of urban fabric before (left) and after (right) regeneration (Source: self-drawn by the author).

5.1.2.2. Accessibility to Different Types of Public Spaces (Figure 8).

These are the most basic and important points that affect people’s perception of a specific public environment. Compared to Bell Tower Street was mixed with people and vehicles causing congestion and clutter before, after the regeneration, three main levels of public spaces have been formed. Firstly, all the streets and lanes were changed to pedestrian with much higher quality. Based on historical records, the streets were connected into a network (some of the streets that existed historically and were later blocked were restored). Secondly, some of the transitional spaces between buildings and streets are enlarged into small squares. Thirdly, the courtyards of buildings in the traditional Chinese courtyard form are open to the public, which is an important carrier of people's perception of the historic environment and life style. Meanwhile, all the public spaces are accessible to all people. This is conducive to the improvement of the vitality and social value of the space.

Figure 8.

Analysis of accessibility to different types of public spaces diagram (Source: self-drawn by the author).

Figure 8.

Analysis of accessibility to different types of public spaces diagram (Source: self-drawn by the author).

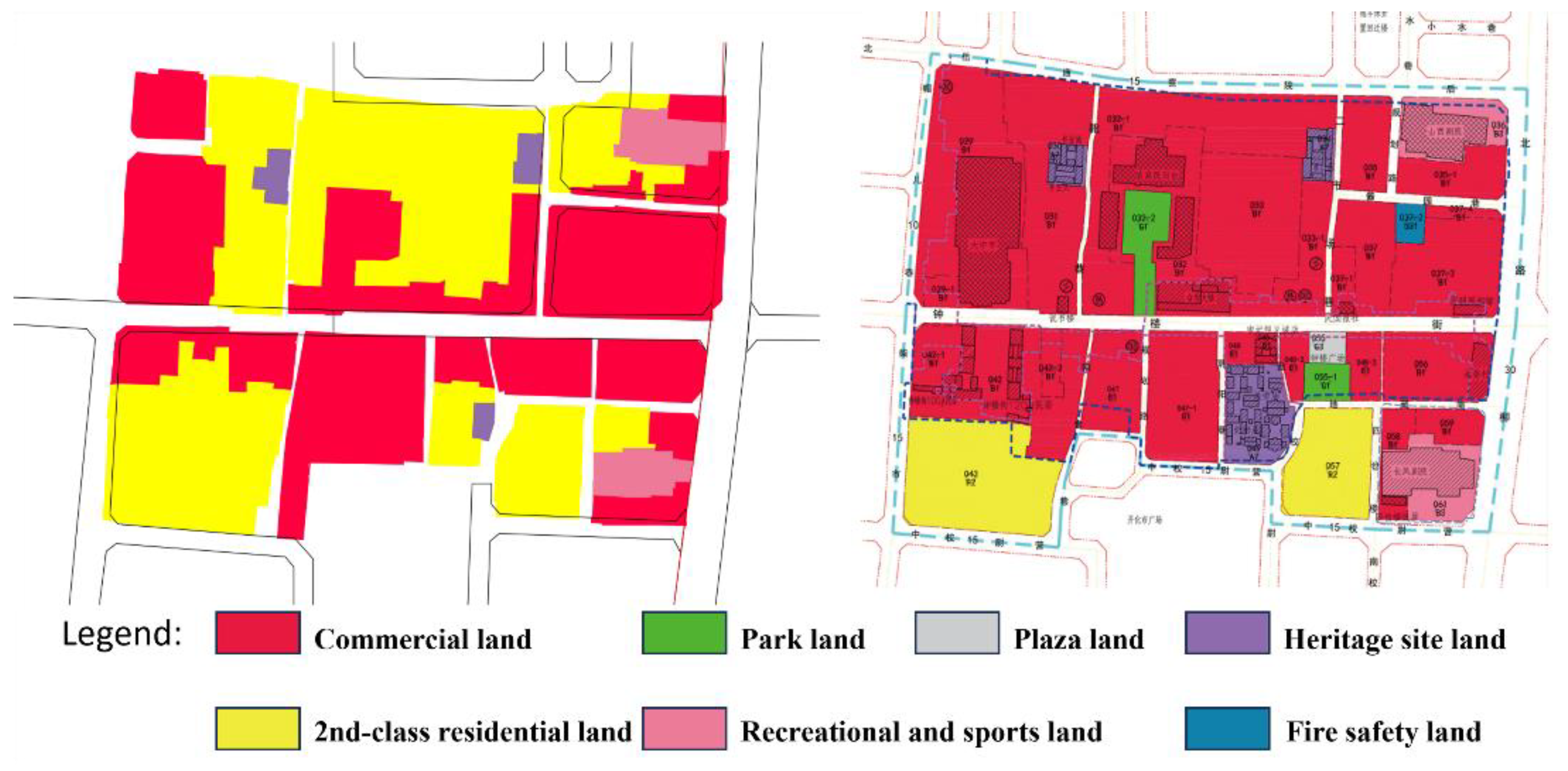

5.1.2.3. Mix of Land Uses.

Public green space, land for cultural facilities, cultural relics and monuments, commerce, and for municipal facilities have been increased. Residential land has been greatly reduced. It can be said that the residential function of the original residents is reduced and the public function for the citizens is increased. During the project planning phase, there has been debate regarding whether the original residential area should be transformed into cultural and commercial spaces. Experts believe that since Bell Tower Street represents the collective memory of the people of Taiyuan, its traditional historical and cultural resources should be made accessible to all residents of the city. Visitors to Taiyuan should also have the opportunity to experience it. As cultural commerce often requires economies of scale, it is suggested that Bell Tower Street should be developed into a historic and cultural commercial hub, a cultural landmark for tourism, rather than being transformed into a residential area for the rich.

Figure 9.

Mix of land uses analysis diagrams before(left) and after(right) regeneration (Source: the left one is self-drawn by the author, the right one is from Taiyuan Municipal Planning Bureau Planning Public Notice Website

http://ghzy.taiyuan.gov.cn/doc/2021/03/11/1064955.shtml).

Figure 9.

Mix of land uses analysis diagrams before(left) and after(right) regeneration (Source: the left one is self-drawn by the author, the right one is from Taiyuan Municipal Planning Bureau Planning Public Notice Website

http://ghzy.taiyuan.gov.cn/doc/2021/03/11/1064955.shtml).

5.1.3. At Micro (Plot & Building) Scale

At the Micro level (architectural scale), the research is based on the aspects of restoration measures, architectural style, space composition, and constructive systems, to study how to balance the historical, artistic, and use values in preserving a building to maximize its overall public value.

5.1.3.1. Restoration Measures.

At the practical level, with the principle of ‘restoring the old as the old’

1, to assign restoration measures to historical buildings, a comprehensive evaluation is conducted based on factors such as protection classification, age classification, number of building floors, structural classification, and building quality. Although the assessments are based on single buildings, the measures are delimited by plots. Different restoration measures for the buildings are determined (

Figure 10):

- 3.

New construction at the original site. For buildings with landmark and symbolic significance, such as the Bell Tower (built in 1583, demolished in 1935) and the Anchasi memorial archway. reconstruction is conducted based on written records and image data, following the principle of the original location, hight, appearance, and construction techniques. For some other buildings like Daning Hall, due to the identification of the main structure of the building as a Class D (the highest level) dangerous building, demolition and reconstruction was carried out. From the perspective of the authenticity of the Western world, the newly constructed historical buildings are forgeries. Leite, R.P. [

43] takes it as the spectacularization of culture intended to turn history and culture into consumable commodities through a strong visual appeal. However, some important historical landmarks in China have indeed undergone several reconstructions in history. Bell Tower is still the 'objectivation of the spirit' of the succession [

44] of Taiyuan Citizens which has social benefits such as aesthetic, cultural, and educational significance.

- 4.

Appearance restoration: Daily maintenance, protection reinforcement, current rectification, and key restoration are conducted for cultural relics and heritage buildings at all levels.

- 5.

Maintenance and improvement: Historic buildings in the neighbourhood are maintained, reinforced, and restored.

- 6.

Exterior maintenance: For buildings that meet the requirements of the urban appearance, rectification requirements are proposed, and the building exterior is repaired according to the historical appearance requirements.

- 7.

Renovation and regeneration: For modern buildings that do not conform to traditional aesthetics but have a structurally sound foundation, preservation and reinforcement measures are carried out, and facades are renovated and renewed to match the traditional aesthetics.

- 8.

Demolition. General buildings that do not meet structural requirements or have unauthorized construction, and modern simple buildings that do not match the urban appearance, are recommended for demolition.

Compared with the past, the direct impact of the regeneration on the lives of citizens is that Taiyuan people have places willing to go on weekends, or when friends come from other places, they can take them to this street representing Taiyuan's characteristics. It aroused the pride of the once prosperous people in Taiyuan in history and the identity of Taiyuan citizens.

5.1.3.2. Architectural Style.

Apart from preserving cultural heritage sites and historic buildings, important Ming and Qing dynasty architectures were reconstructed, most Republican-era buildings were restored, some post-1949 buildings were retained, and a small number of modern buildings were inserted. Ultimately, a comprehensive architectural style was formed that was mainly based on the Republican-era style, while also compatible with the styles of various periods, reflecting the overall development and changes of the city.

As to the external style of buildings, traditional facades of small and medium-sized commercial buildings were added to the buildings, and the traditional roof combination of the quadrangle courtyard was used. Regarding construction technology, skilled craftsmen were gathered. Provincial intangible cultural heritage inheritors and masters of arts and crafts in Shanxi province were invited such as brick carving, wood carving, and painting to tailor traditional buildings.

5.1.3.3. Space Composition and Constructive Systems.

Large spaces that meet modern commercial needs were used as much as possible. For the reconstruction and protection of historic buildings, it was important to restore the original architectural structure as much as possible based on historical records (

Figure 11 Cases 1 &2). For the buildings renovated, the main strategy was combining brick and wood construction to frame the structure, blending modern commercial space with traditional architectural styles. For example, (In

Figure 11 cases 3 &4) add a traditional-style porch to the street-facing facade.

5.2. Economic-Social Dimension: Urban Regeneration Modes and Urban Governance Strategies Strengthens Public Rights

5.2.1. Exploration of Regeneration Mode and Urban Governance Strategies from 2014 to 2017.

For the regeneration mode of the area, the government clearly positioned the Bell Tower block as a ‘cultural and commercial district, a cultural name card of the city’ in various policy documents from 2014 to 2015. The municipal government adopted a ‘comprehensive regeneration, demolition, and reconstruction’ mode for Bell Tower Street plan. Only officially protected monuments and sites, traditional buildings with protection value, and the original street and lane texture in the block were retained. All other buildings were demolished, and large-scale underground space development was planned to obtain development funds. The block style selected was the transition period from Qing Dynasty to the Republic of China, when Bell Tower Street was prosperous. The local traditional courtyard unit form was collaged and replicated in space, finally creating the image of a ‘historical space’.

For regeneration funding, since state-owned capital was insufficient, the municipal government explored joint development options, engaging partners and attracting capable developers. Discussions were held with real estate firms Beijing A Company and Shenzhen B Company in 2014 and 2015. However, after assessing business income and market potential, these companies concluded that the project wouldn't yield profits. Consequently, the attempt to lure developers for commercial investment and renovation funds proved unsuccessful. In terms of public participation, traditional brand owners, as stakeholders, have undergone a process from individuals to a group, from passive to active participation. In the process of bargaining with the government, merchants gradually realize that they are the carriers and exhibitors of the traditional commercial and cultural characteristics, and should have greater rights. In 2014, the main shop owners established the ‘Autonomous Renovation Committee’ spontaneously, which took responsibility for ensuring that shop owners and residents express their demands to the government reasonably.

In the 2017 annual work report, the municipal government once again included the Bell Tower Street project, positioning it as a ‘cultural business card and cultural living room’ and removing the commercial positioning, emphasizing the cultural positioning. This indicates a change in the government's positioning of Bell Tower Street. However, from 2014 to 2017, the municipal government was unable to find a satisfactory regeneration plan in the contradiction between development and protection.

5.2.2. Transformation of Urban Regeneration Mode in 2020

Financial security is the fundamental constraint for advancing urban regeneration. At the same time, the source of funding is also an important factor affecting the quality of the project: urban regeneration that relies entirely on government investment is not sustainable, but fully market-driven operations are difficult to achieve financial balance. Moreover, excessive reliance on capital may fall into the trap of maximizing profits, leading to a decline in project quality. In 2020, the municipal government finally determined the funding source and regeneration model for the renovation of Bell Tower Street. This project adopts a multi-channel investment approach - a combination of government investment and market-oriented operations. This approach not only solves the funding problem and promotes the rapid completion of the project in the short term, but also establishes government leadership to ensure the accuracy and completeness of achieving the project goals.

The government platform's market investments aim for financial balance rather than profit. The total investment of the project (

Table 1) is about 3 billion yuan, of which approximately 1 billion yuan is used for infrastructure construction (for instance, urban networks for supply services). This portion of expenditure is government-funded and is not included in the calculation of the financial balance. If it were included, the project would result in a loss. For financial balance, approximately half of the rights to use land and houses and one-fourth of the rights to use the houses would be nationalized through expropriation. Afterward, the government platform used these expropriated rights as collateral for loans to be repaid through 25-30 years of rent. The remaining one-fourth of ownership stood owned by traditional brands or former state-owned enterprises (Source: Dean of Design Institute). The property rights after the renovation of the Bell Tower Street historic district are based on a mixed ownership structure, mainly belonging to public authority.

Compared to the 2014-2017 renovation model, the 2020 mode is different in that most of the land usage rights were sold to developers in the former, while in the latter the land is still owned by the government. The proportion of building demolition was higher in the former than in the latter. The latter invested more in infrastructure, public welfare, and cultural facilities than the former. The investment is mainly from the government and a State-owned Investment and Financing Company, and the Operating profit goes back to the company which is a platform. Therefore, it can be concluded that Taiyuan Bell Tower Street has public-oriented ownership of means of production and the ways of space to be used.

5.2.3. Roles of Government, Market, and Society

5.2.3.1. Roles of Government.

The roles of the Central government and provincial government are mainly about institutional constraints, policy guidance, supervision, and inspection. For example, they enact relevant laws and regulations to constrain the behavior of local governments in the protection and regeneration of historical streets; They are not directly involved in local government urban regeneration efforts, but supervise and inspect the protection and regeneration work.

Municipal Government and District Government mainly organize, coordinate, and participate in implementation. In detail, the municipal government proposes a motion for the regeneration of historic neighborhoods; organizes the preparation of plans; establishes regeneration organizations; determines funding sources; organizes public participation, and introduces regeneration policies. The Yingze district government follows the instructions of the municipal government to complete basic information surveys of the neighborhood, conduct surveys of residents’ and merchants' opinions, participate in the formulation of regeneration policies, and carry out demolition and resettlement work.

5.2.3.2. Roles of Market.

There are two main companies involved in the market role, which are a state-owned investment and financing company (Yingze District Asset Management Company) and China Resources Real Estate Development Co., Ltd. as a business partner. The former one act as the development department of the project, responsible for the construction and financing of the project on behalf of the government. Profit is a secondary objective to it. At the same time, the latter one is responsible for brand business attraction and operation in the commercial aspect.

5.2.3.3. Roles of Society.

Stakeholders of society are collaborators and protestors in the regeneration of Bell Tower Street, including:

- 9.

Owners of Historical Protected Buildings. Some property owners agreed to have their property rights expropriated by the government. However, some others, after several rounds of negotiation, still did not agree or protested against the expropriation plan. In the end, the property owners kept their property rights and agreed to carry out the building renovation work on their own。

- 10.

Traditional brand shop owners. With support from the government and the chance of regeneration, the traditional brand shop owners promoted the development of the brands.

- 11.

Other Residents of the neighborhood. Public housing residents, who have no property rights, must unconditionally implement the government's policy of ‘relocation to other places’. Private property residents adopt the mode of ‘relocation to other places, compensation with money, and relocation nearby’.

- 12.

Design Institute: completing the preparation work of planning and design and the statutory procedures; using design concepts and professional knowledge to support government intentions; acting as a coordinating role among all parties as needed during implementation [

45].

- 13.

Experts. During different stages of the protection and renovation process, the government organized several expert seminars, in which experts provided third-party consulting advice on heritage protection, renovation models, business planning, etc.

- 14.

Media. Assisting the government in positive publicity and guidance of the project at different stages.

- 15.

Other citizens. The high concern of citizens plays a supervisory and promoting role in the regeneration of Bell Tower Street.

5.2.4. From Informal to Formal Channels, the Rights of All Stakeholders Were Exercised Guided by Public Value

In 2014-2017, under the government and enterprise-led model, some stakeholders maintained their rights through informal channels. Informal approaches include the establishment of an ‘Autonomous Renovation Committee’ by some traditional brand merchants with the tacit approval of the government. Some people expressed their protests by writing letters to the municipal government or collective petition in front of the city hall. In 2020, under a governance model combining government leadership and public participation, the government, guided by public values, aligns the values of various stakeholders and gains cohesion. At the same time, guiding public participation can not only mobilize the enthusiasm of relevant parties and ensure the smooth progress of the project but also integrate social resources and improve the professionalism and precision of the project. This ensures that the project moves toward achieving social and economic benefits.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

In this paper, we provide an integrated framework for discussing how various aspects of spatial form and urban governance contribute to public value in the regeneration of historic districts. Historic environment regeneration represents a material spatial expression characterized by the re-creation of value, while also reconfiguring social relationships related to governance systems and spaces. By introducing the concept of public value for analysis, we can better examine the goals, spatial forms, and urban governance performance of historic environment regeneration. The shared value, in the form of historic spaces and public services, is provided freely and equally to all members of society. This aligns with people's aspirations for a better civic life and effectively validates

By investigating the successful regeneration of Taiyuan Bell Tower district, we have found that a sustainable regeneration strategy should encompass the following two aspects: From a spatial perspective, policymakers should conduct a comprehensive analysis of the public value of historic districts at three levels to then determine appropriate regeneration strategies. From the standpoint of urban governance, it is essential to consider the balance of interests among government, market, and residents, designing suitable renovation and management models.

This study provides two contributions to literatures. Firstly, this article establishes a theoretical framework from the perspective of public value, which offers enhanced sustainability compared to existing literature. Secondly, based on the proposed framework, this article provides a detailed analysis of the regeneration of Taiyuan's Bell Tower district, comprehensively showcasing the successful experiences of historic district revitalization. In practice, this framework can help governments, policymakers, planners, etc. in other unimplemented, ongoing, and completed historic environment regeneration projects to evaluate the projects and adjust policies and strategies.

This study suffers serval limitations that may addressed by future research. First, we applied our framework of regeneration strategies on only one case study. More diverse and similar cases would be analyzed to test the applicability and validity of the framework. Second, the data in this article are primarily derived from interviews with key individuals rather than through widespread surveys or more quantitative measurement methods. Therefore, future research could utilize a more comprehensive data collection approach for analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Z.; methodology, R.Z. and M. M. C; software, R.Z.; validation, R.Z.; formal analysis, R.Z. and M. M. C; investigation, R.Z.; resources, R.Z.; data curation, R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.Z.and M. M. C; visualization, R.Z. and H. L.; supervision, M. M. C and M. B. G; project administration, R.Z.; funding acquisition, R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research was funded by China Scholarship Council, Public Postgraduate Program for Building High-level Universities in China (Scholarship in Cooperation with the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Spain), under Grant Liujin Europe [2021] 339.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained from Taiyuan Architectural Design and Research Institute and my first-hand material when I was working in Taiyuan Urban and Rural Planning Design and Research Institute. Due to intellectual property rights, the data are not publicly available. Readers interested in accessing these data should contact the corresponding author, by e-mail: 1010236582@qq.com. The data were used under the terms of the agreement for the sole purpose of this research.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere appreciation to Taiyuan Architectural Design and Research Institute and the Taiyuan Urban and Rural Planning Design and Research Institute for their assistance during this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ding, F.; Ren, Y.; Goudos, S.; Zhao, Y. Analysis of Public Space in Historic Districts Based on Community Governance and Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 81021–81032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B. International Forum on High Quality Urban Development and the 13th Gardening Summit. Weixin Official Accounts Platform 2023. Available at: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/HmTBrs8JDqJCkRxQdHd96A.

- Yang, B. The Core Essence of Implementing Urban Regeneration Initiatives. China Survey and Design 2021, 10, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, J. Stage Logic and Sustainable Dynamic Innovation of Historic Areas Regeneration: A Case Study of Nanjing Old Town South. Urban Development Research 2022, 1(29), 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Cong, C.; Chakraborty, A. Exploring the Institutional Dilemma and Governance Transformation in China’s Urban Regeneration: Based on the Case of Shanghai Old Town. Cities 2022, 131 (December), 103915. [CrossRef]

- Clavir, Miriam. Preserving What Is Valued: Museums, Conservation, and First Nations. Google Books. UBC Press. 2002.https://books.google.com.hk/books/about/Preserving_what_is_Valued.html?id=ZlQb2Q5Q4TkC&redir_esc=y.

- Fredheim, L. H.; Khalaf, M. The Significance of Values: Heritage Value Typologies Re-Examined. Int. J. Heritage Stud. 2016, 22(6), 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guallart, Vicente, ed. General Theory of Urbanization 1867. Barcelona: Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia. 2018.

- Moore, Mark H. Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.1995.

- Benington, J. Creating the Public in Order to Create Public Value? Int. J. Public Admin. 2009, 32 (3-4), 232–249. [CrossRef]

- Clark, K. Capturing the Public Value of Heritage. Academia.edu. English Heritage. 2006. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/3639888/Capturing_the_Public_Value_of_Heritage.

- Ćwiklicki, M. Comparison of Public Value Measurement Frameworks. Zarządzanie Publiczne 2016, no. 35, 20–31. Available at: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=397858.

- Conzen, M. R. G. Historical Townscapes in Britain: A Problem in Applied Geography. In Northern Geographical Essays in Honour of G. H. J. Daysh, edited by J. W. House, 56-78. Newcastle upon Tyne: University of Newcastle upon Tyne, 1966.

- Sadeghi, G.; Li, B. Urban Morphology: Comparative Study of Different Schools of Thought. Curr. Urban Stud. 2019, 07(04), 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kossak, F. Building Typology as a Generator of Urban Form for Urban Design Project. Cities Assem. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Study on Spatial Governance of Urban Renewal in China Transformation Period: Mechanism and Mode. Nanjing University, 2016.

- Stone, C. N. Looking back to Look Forward. Urban Affairs Review 2005, 40(3), 309–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox, R. Heritage and Politics in the Public Value Era: An Analysis of the Historic Environment Sector, the Public, and the State in England since 1997. Etheses.whiterose.ac.uk, January 1, 2016. Available at: https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/13646/.

- He, Y.; Deng, W. From Management to Governance – the Role of Government in Historical Block Conservation. Urban Planning Forum 2014, 6, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Nocca, F. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool. Sustainability 2017, 9(10), 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí Casanovas, M.; Roca, E. Urban Visions for the Architectural Project of Public Space. J. Public Space 2017, 2(2), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.; Santos Cruz, S.; Pinho, P. Publicness of Contemporary Urban Spaces: Comparative Study Between Porto and Newcastle. J. Urban Plann. Dev. 2020, 146(4), 04020033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Jiang, X.; He, Y.; Martí Casanovas, M. Research on the Historical Types of Small Public Spaces from the Perspective of Urban Morphology: Taking Barcelona as an Example. Urban Planning Int. 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, Y.; Stalcup, M. A Heterotopology of Urban Margins: Publicness in the Space of the City. City Soc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, I. Y.; Luo, J. M.; Chan, E. H. W. Spatial Justice in Public Open Space Planning: Accessibility and Inclusivity. Habitat Int. 2020, 97 (March), 102122. [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.; Wang, W.; Masui, T. Analysis for Conservation of the Timber-Framed Architectural Heritage in China and Japan from the Viewpoint of Authenticity. Sustainability 2023, 15(2), 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y. Research on the Connotation and Applicability of the Concept of ‘Repair the Age as Aged’ in Architectural Heritage. Shandong Acad. Arts, 2022.

- He, S.; Wu, F. China’s Emerging Neoliberal Urbanism: Perspectives from Urban Redevelopment. Antipode 2009, 41(2), 282–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdini, G.; Frassoldati, F.; Nolf, C. Reframing China’s Heritage Conservation Discourse. Learning by Testing Civic Engagement Tools in a Historic Rural Village. Int. J. Heritage Stud. 2016, 23(4), 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L. International Influence and Local Response: Understanding Community Involvement in Urban Heritage Conservation in China. Int. J. Heritage Stud. 2013, 20(6), 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Sun, M. Research on Several Issues of Historic District Protection and Planning in China. Urban Plann. 2001, 10(25), 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Pan, L. Practice of Multi-stakeholder ‘Participatory Planning’ in Historic District Regeneration—Taking the Renovation and Reconstruction of Shijia Hutong as an Example. In Vitality in Urban and Rural Areas: Better Living Environment—Proceedings of the 2019 China Urban Planning Annual Conference (02 Urban Regeneration).

- Kling, R. W.; Revier, C. F.; Sable, K. Estimating the Public Good Value of Preserving a Local Historic Landmark: The Role of Non-Substitutability and Citizen Information. Urban Stud. 2004, 41(10), 2025–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, K. Capital, Volume 1. Lulu.com, 2018.

- Langstraat, F.; Van Melik, R. Challenging the ‘End of Public Space’: A Comparative Analysis of Publicness in British and Dutch Urban Spaces. J. Urban Des. 2013, 18(3), 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Shang, Q. An Observation on Urban Regeneration in Beijing Old City during 2004-2016 and the Role of Architects. [Online]. Available: https://www2.fag.edu.br/professores/solange/ANAIS%20UIA%202017%20SEOUL/papers/Full_paper/Paper/Oral/PS1-52/O-0489.pdf.

- Yung, E. H. K.; Chan, E. H. W.; Xu, Y. Sustainable Development and the Rehabilitation of a Historic Urban District - Social Sustainability in the Case of Tianzifang in Shanghai. Sustainable Dev. 2011, 22(2), 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B.; Ng, M. K. Urban Regeneration and Social Capital in China: A Case Study of the Drum Tower Muslim District in Xi’an. Cities 2013, 35 (December), 14–25. [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Zhang, T.; Yin, Z.; Zhu, D.; Wang, K.; Dong, K.; Fan, J. , et al. Chinese Style Urban-Rural Modernization: Connotation, Characteristics, and Development Path. Urban Plann. Forum, 2023, 1.

- Li, J.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Roders, A. P.; Van Wesemael, P. Community Participation in Cultural Heritage Management: A Systematic Literature Review Comparing Chinese and International Practices. Cities 2020, 96 (January), 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M.; Heath, T.; Oc, T.; Tiesdell, S. Public Places-Urban Spaces. Oxford: Architectural Press, 2003.

- Er, V. Investigating the Morphological Aspects of Public Spaces: The Case of Atakum Coastal Promenade in Samsun. Open.metu.edu.tr, 2019. Available at: https://open.metu.edu.tr/handle/11511/44036.

- Leite, R. P. Consuming Heritage. Translated by D. Rodgers. Vibrant. Virtual Brazilian Anthropology 2013, no. v10n1 (October), 165–189. Available at: https://journals.openedition.org/vibrant/568.

- Whitehand, J. W.; Gu, K. Urban Conservation in China: Historical Development, Current Practice and Morphological Approach. Town Plann. Rev. 2007, 78, 643–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.; Zhang, Y. Collaborative Approaches to Urban Governance Model of Historic Districts: A Case Study of the Yu’er Hutong Project in Beijing. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2022, 26 (2), 332–350. Available at: https://ideas.repec.org/a/taf/rjusxx/v26y2022i2p332-350.html.

Notes

| 1 |

The principle of “restoring the old as the old” in heritage protection refers

to a conservation approach where historical structures or artifacts are

repaired, maintained, or restored in a manner that preserves their original

historical appearance and character as much as possible. This principle

emphasizes the importance of retaining the authenticity and integrity of

cultural heritage sites and items, ensuring that any interventions are minimal

and respectful of the original fabric and design. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).