1. Introduction

Circumcision is one of the oldest and most common surgical procedures [

1,

2,

3]. In erstwhile times, religious, covenant establishment (example of Genesis 17:10 in the Bible), medical, initiation ritual, and a rite of passage into manhood were major indicators for circumcision [

4,

5,

6]. These indicators defined the place and person to conduct the procedure and most often the outcomes could be positive (survival) or detrimental (death) to the individual being circumcised.

Among the AmaXhosa, in South Africa in particular, circumcision is of paramount importance and highly valued by every young man, because it symbolises communal pride and individual worth [

7]. Nearly 27 million voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) had been performed in 15 priority countries by the end of 2019, and more than 60% of the 2020 VMMC target had been reached before services were disrupted by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic [

8].

With advancement in biomedical science and changing health transition of populations aligned with current pandemics such as HIV/AIDS, male circumcision is not only an indication for religious, cultural, or medical fulfilment, but is now considered as a public health measure to reduce the incidence of HIV infection and the overall prevalence rate of this disease among populations [

4,

5,

9].

The World health Organisation (WHO) and UNAIDS organised a consultation of modelers and policymakers to assess various models and projections and develop key messages to guide strategic directions over the following five years, this was done in anticipation of a new phase of VMMC interventions, which was expected to last until 2021 [

10]. There has been a significant investment in implementing VMMC programmes for HIV prevention in Southern and Eastern Africa since the WHO/UNAIDS recommended that medical male circumcision be considered an additional method of HIV prevention in 2007 and for it to be rapidly scaled up in countries with low prevalence of circumcision and high prevalence of HIV [

10]. About 11.7 million male adolescents and adults have been circumcised by the end of 2015 [

10].

Other publications predicted that an extensive practice of VMMC in sub-Saharan Africa would prevent almost six million HIV infections over 20 years, as would three million deaths among both men and women [

11]. Three randomised controlled trials (RTCs) conducted in different African countries involving predominantly young, HIV-negative adult males found conclusive evidence that male circumcision has a protective effect against HIV infection in men [

12]. The trials, which took place in Orange Farm (South Africa), Kisumu (Kenya), and the rural Rakai Province of Uganda, showed that circumcision reduces the risk of HIV acquisition by approximately 50-70%, and due to these clear results, the authors reported that it was considered unethical not to offer circumcision to the control group before the planned end date of the trials [

12].

In certain African regions, combining medical male circumcision with traditional manhood initiation ceremonies faces challenges due to cultural reasons; Wilcken et al. (2010) reported that 70% of men express fear of stigma if they undergo medical circumcision; additionally, initiates may hesitate to seek post-circumcision care at medical facilities because leaving the initiation school is considered shameful in certain contexts [

13]. For example, in Libode village of Nyandeni sub-district in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, VMMC is said to be culturally unacceptable [

14].This is because male circumcision is regarded as a cultural practice that serves as a transition into manhood [

14]. In some communities respected authorities like traditional leaders, argue that VMMC is

undermining their culture and customs [

15]. Twenty-eight traditional initiates admitted to a South African district hospital in the Eastern Cape province after complications of their traditional male circumcision (TMC) previously stated that “a real man does not use western medicine but traditional medicine, therefore traditional male circumcision (TMC) is number one,” [

16].

The main aim of the study was to examine the level of knowledge and acceptability of VMMC among young males in a selected high school in the rural Eastern Cape in South Africa. It was conducted to identify sources of information and identifying socio-demographic factors that influence the acceptability of VMMC as an HIV prevention intervention among Grade 11 and 12 males aged 15 to 20 years. The study was conducted to give a better understanding about VMMC and the benefits after circumcision as compared to TMC which is mostly done by non-health professionals and lay members of the community. Even though it’s not in most initiates, where there are complications, they often lead to hospital admissions, penile amputations and or death of those affected [

17].

The results of this study are intended to be a useful reference point for educational purposes for the acceptance of VMMC, and to circumcise safely whilst respecting the practice of culture. The findings, and recommendations will help to put mechanisms in place to curb the high number of admissions to hospitals due to septic circumcision, dehydration, gangrene, amputations, and death related to TMC. This study is also intending to make a significant impact on the life of people in the study population and other similar populations.

The findings and recommendations of the study will influence policy and decision makers, government, NGOs, and communities. Findings of this study are also intending to improve sexual reproductive health of young males seeking circumcision. Results of this research will contribute to the body of scientific knowledge around circumcision. A copy of this research will be made available to the study site and the neighbouring schools and communities. Lastly, the study will also help the families, communities, and society at large to avoid complications resulting from TMC that may lead to loss of life by referring their children to health facilities for VMMC before going to the ‘mountain’ or TMC site for manhood laws (Umthetho).

2. Materials and Methods

Study design. A descriptive quantitative cross-sectional study was used to answer the research question and objectives. This design was chosen because it was a cost-effective way to answer the research question at a snapshot without the need for a follow-up. The study was conducted on the 23rd of March 2018.

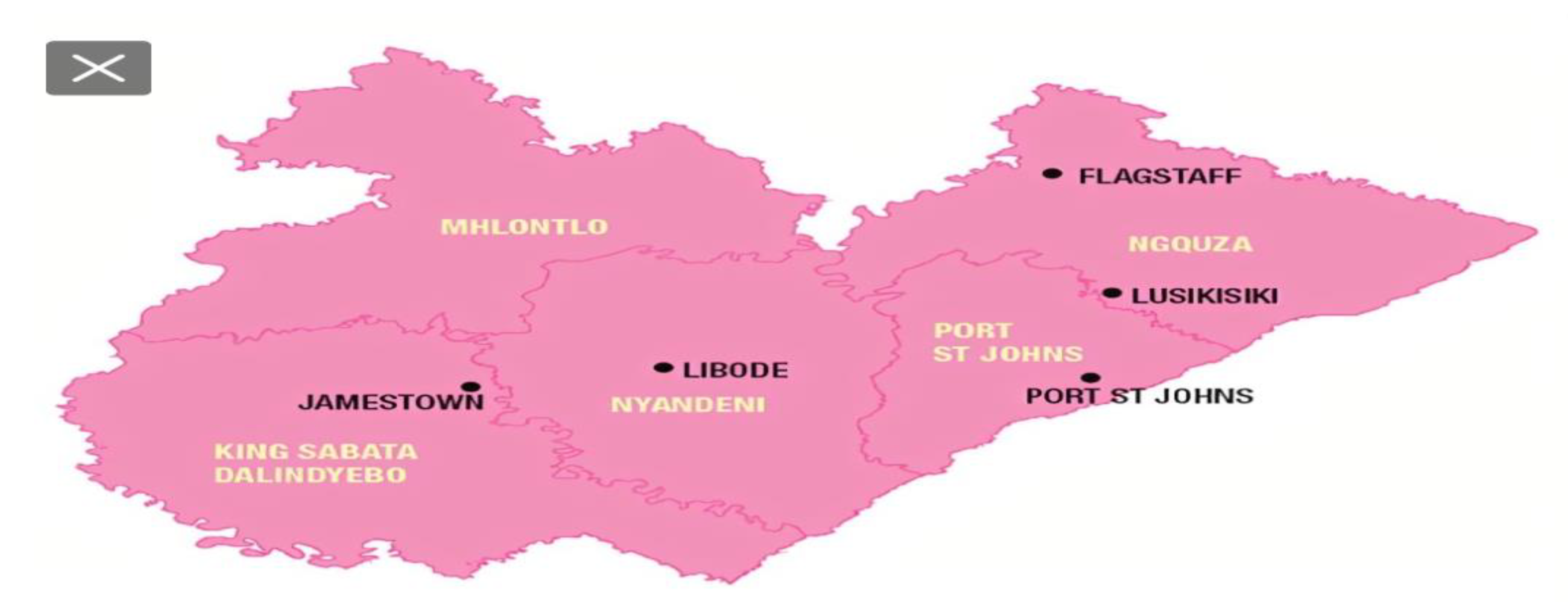

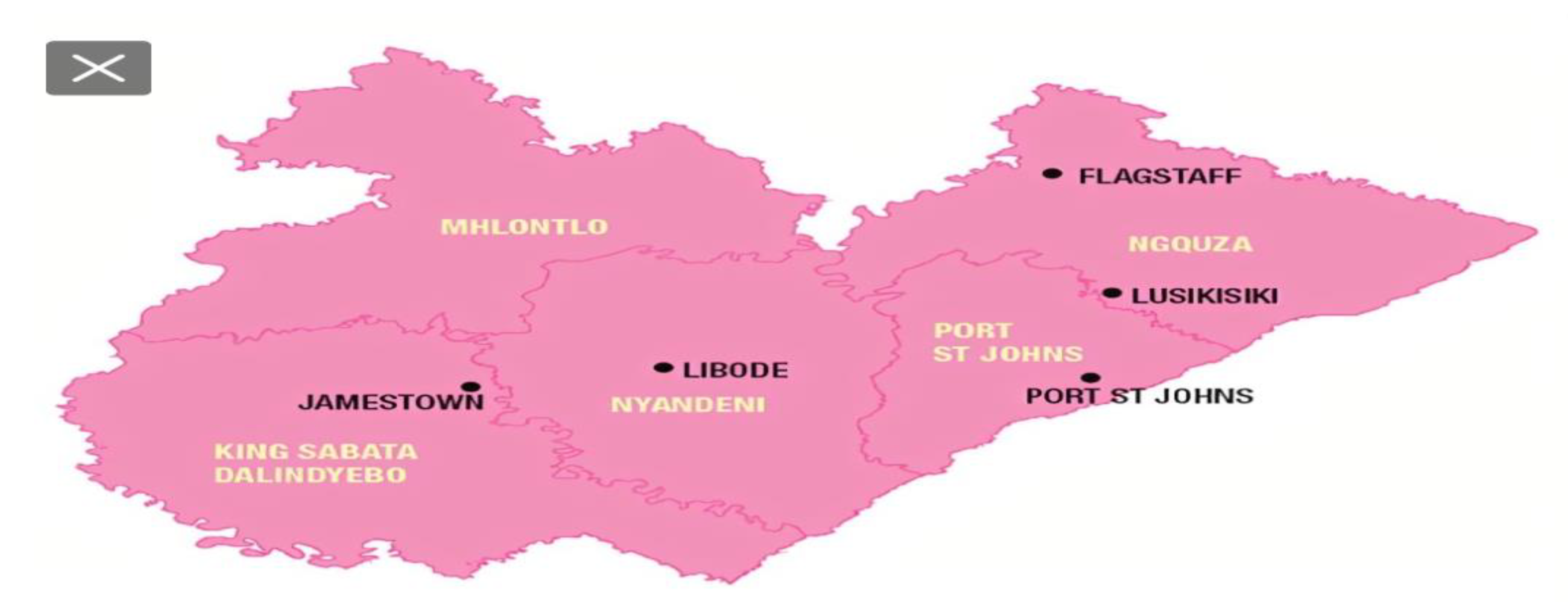

Study setting. Eastern Cape Province is South Africa’s second largest province by surface area and fourth most populous [

18]. The largest district, OR Tambo is one of eight districts in the province, and it has five sub-districts [

18].The study was conducted at a conveniently selected high school located in the small town of Libode in the Nyandeni sub-district.

Study population. The study population comprised all (n=199) the Grade 11 and 12 males aged between 15-20 years regardless of their circumcision status. Absence from school and refusal to consent were the only exclusion criteria.

Sampling and Sample size. The sample size required was determined using the equation for a one-sided 95% confidence interval for a cross-sectional study, ; where z=1.96. The proportion of acceptability of male circumcision (p) was estimated to be 50% since there was no literature guidance; and the desired precision (d) was set at 10%. This then yielded a minimum sample size of 96 which was rounded off to 100. All males in Grades 11 and 12 were assigned random numbers and 100 numbers were randomly drawn with the assistance of Microsoft Excel. Each drawn number was called, and individuals were privately offered an opportunity to consent or refuse participation. All drawn 100 participants accepted. As a result, 57 Grade 12s and 43 Grade 11s were sampled respectively.

Data collection. The Questionnaire (Annexure 1) is a self-administered instrument that sought to find information on socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge of VMMC, perceptions on VMMC and on circumcision practices. The questionnaire was developed in English and IsiXhosa (the local language) to allow for participants to choose a preferred language. A pilot study was conducted among twenty male learners in a different school within the same district to test the reliability of the questionnaire, identify its appropriateness and measure its length. A set of questions were developed and submitted to two public health professionals to ascertain content and context validity of the instrument. Participants were not trained on how to use the instrument, but it was explained to them and circulated for answering. The use of a self-administered questionnaire and monitoring of participants as they completed their questionnaires minimised the possibility of social desirability bias.

Data analysis and management. Categorical data are presented using frequencies, percentages, and graphs. Association between two categorical variables was conducted using the chi-squared statistic or the Fisher’s exact test if the expected frequencies were ≤5. Data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). Logistic regression analyses were performed to compute bivariate associations of purposefully selected variables associated with the acceptability of VMMC. The Odds Ratio (OR) is the measure of association used. The 95% Confidence Interval (95%CI) was used to estimate the precision of estimates. The p-value for statistical significance was set at p-value = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Profile of the Sample Population

One hundred (100) participants were recruited from both Grade 11 and Grade 12. The median age was 19 years. Most of the participants (57%) were in grade 12, Christian (72%), resided in rural areas (79%) and their parents were married/living together (43%). Forty-one (41%) percent reported that their fathers were formally employed while (40%) reported that their mothers were formally employed.

Table 1 is the description of the participants’ socio-demographic characteristics.

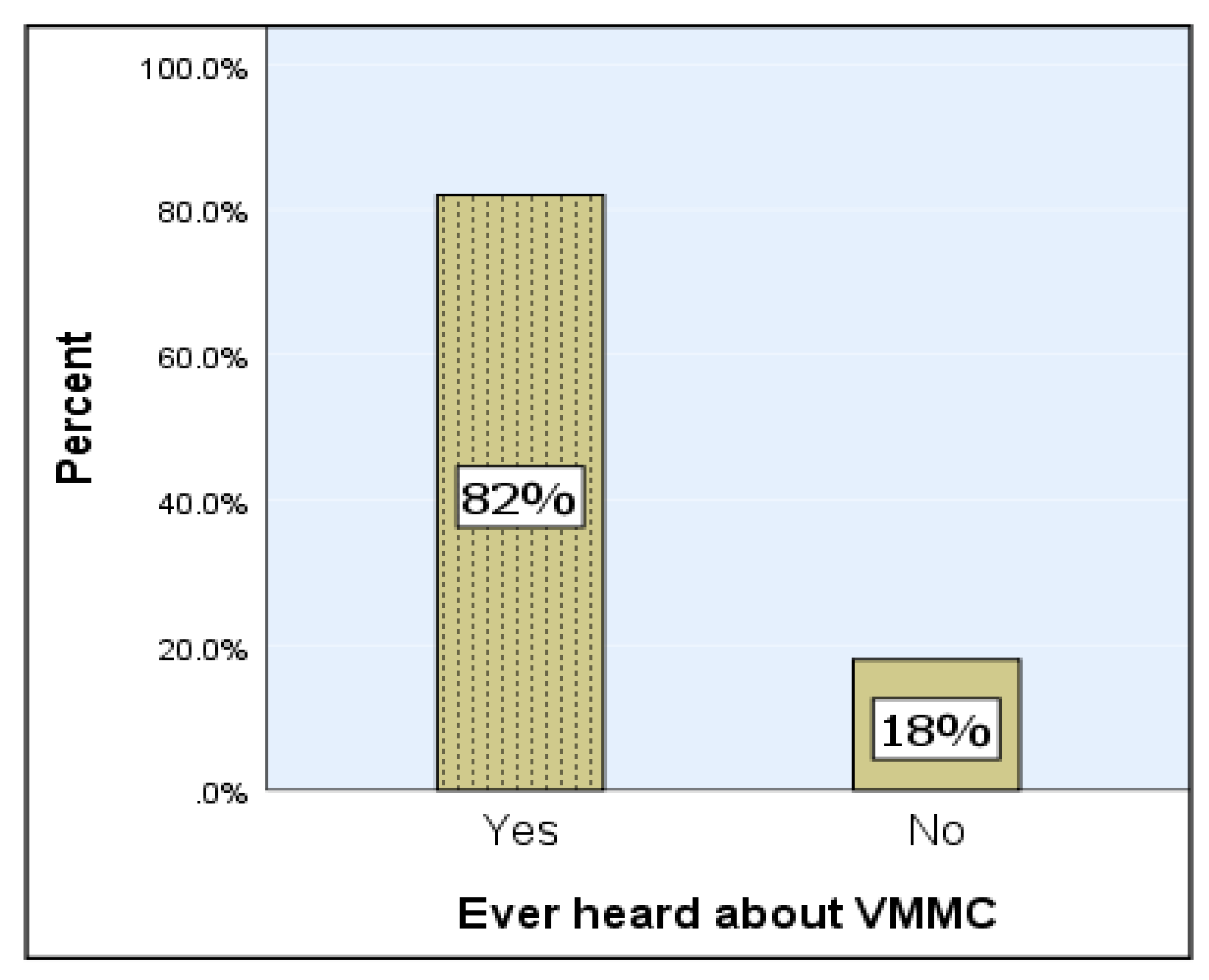

3.2. Source of VMMC Information among the Participants

Respondents were asked to indicate whether they had ever come across any information on VMMC. Most of the participants (82%) indicated that they had received information on VMMC (

Figure 1).

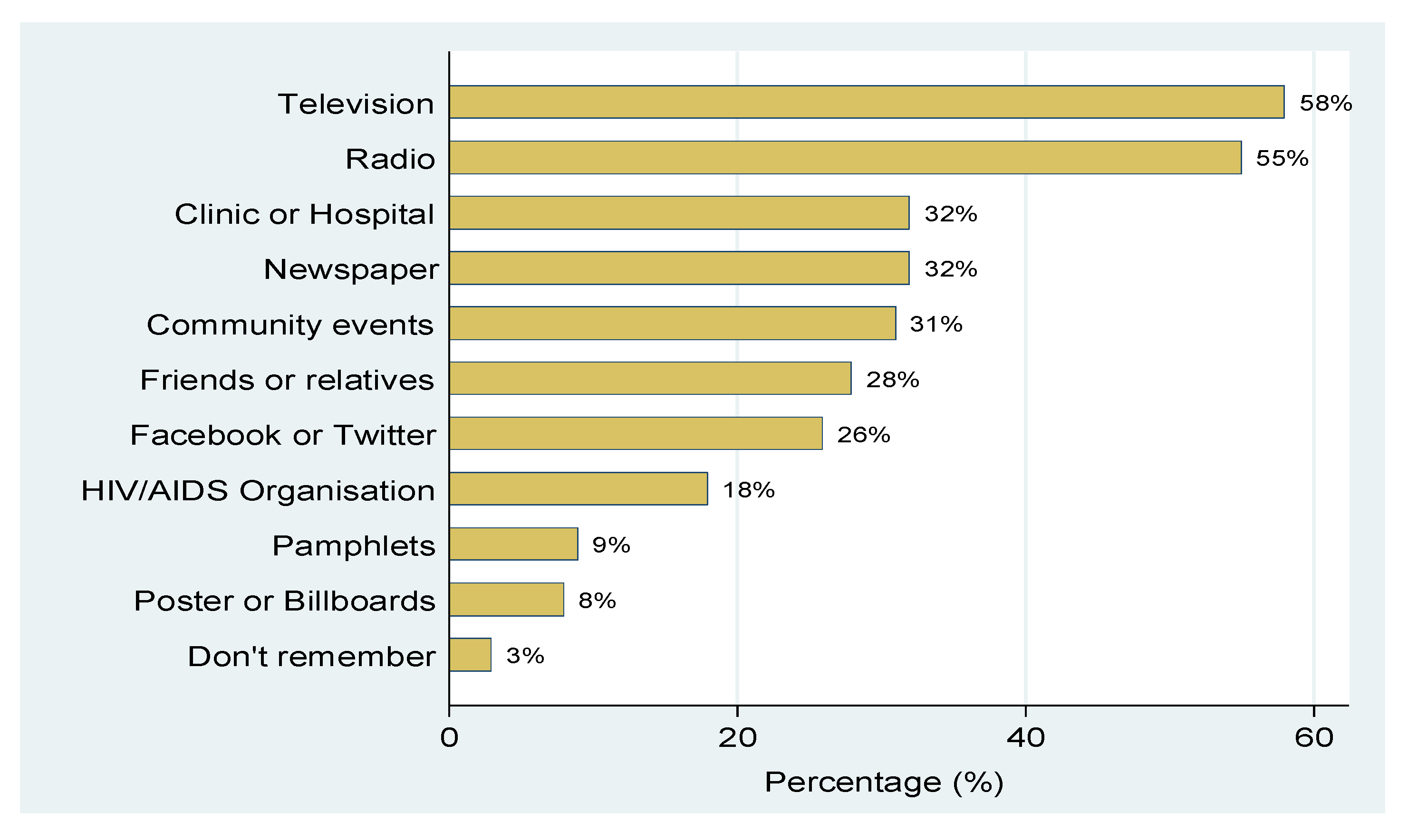

The results presented in

Figure 2 show various sources of information on VMMC, and participants could list more than one source.

Most of the respondents (58% or n=58) cited television as the main source of information for VMMC, followed by radio (55%), clinic or hospital (32%), newspaper (32%), community events (31%), Friends or relatives (28%) and Facebook or Twitter (26%). Three participants (3%) could not recall their source of information.

3.3. Knowledge about VMMC

The overall knowledge score for each variable used to measure knowledge about VMMC is presented in

Table 2.

A comparison of knowledge about VMMC between Grade 11 and Grade 12 shows no statistical differences (

Table 3).

Knowledge of VMMC for Grade 11 and Grade 12 boys was similar. However, a statistical significance was observed for the questions on whether VMMC entirely prevents HIV infection among females (p=0.05). The suggestion that VMMC entirely prevents HIV infection among females was high among participants in Grade 11 (64.3% or n=9).

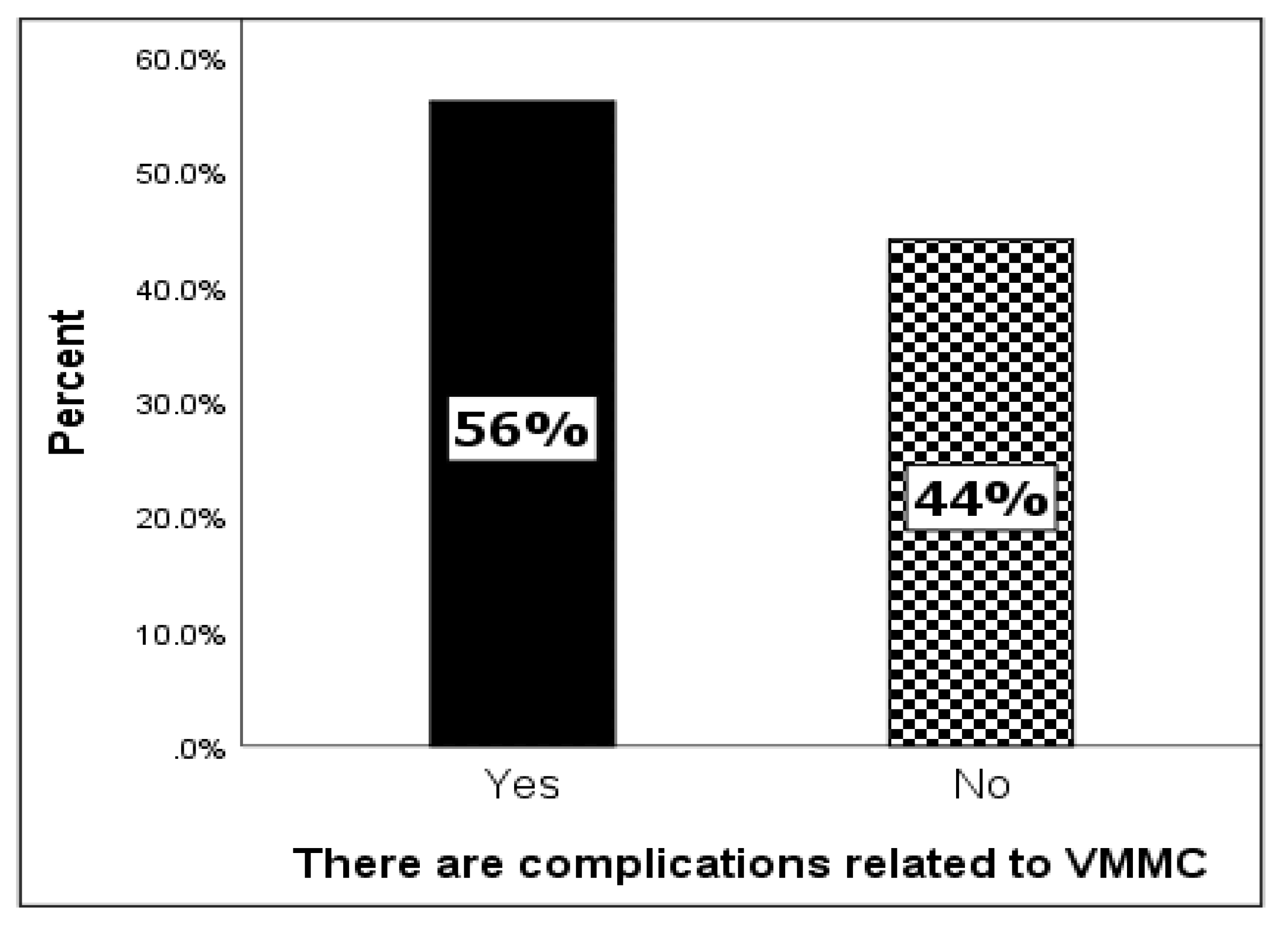

3.4. Knowledge on Complications of VMMC

Among the study sample, 56% indicated that there were complications related to VMMC and 46% indicated that there were no complications related to VMMC (

Figure 3).

The results presented in

Table 4 show the different complications related to VMMC and participants could indicate more than one complication.

Among those who reported that there were complications related to VMMC, most of the participants (46.4%) identified infections (urinary tract infection), followed by “severe pains of the penis” (30.4%) and “wound not healing at 60 days after surgery” (30.4%). Other complications of VMMC identified were “continuous excessive bleeding” (26.8%) and partial penile amputation (16.1%).

3.5. Acceptability of VMMC as an HIV Prevention Intervention

Table 5 shows the level of acceptability of VMMC as an HIV prevention intervention. For personal acceptance, only a minority of the participants (31 participants) would consider undergoing VMMC. Again, 28 and 24 participants suggested that either their parents or their family members would respectively allow them to undergo VMMC. Among the participants, only 14% of their male friends or 27% of their female friends would allow them to undergo VMMC. Respondents thought that, only 16% of the participants’ male schoolmates or 21% of the participants’ female schoolmates would allow them to undergo VMMC. Furthermore, only 14% of the participants suggested that their community members would allow them to undergo VMMC.

3.6. Preferential Type of Circumcision

The type of circumcision preferred was assessed at individual and referral levels. The findings obtained are presented in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

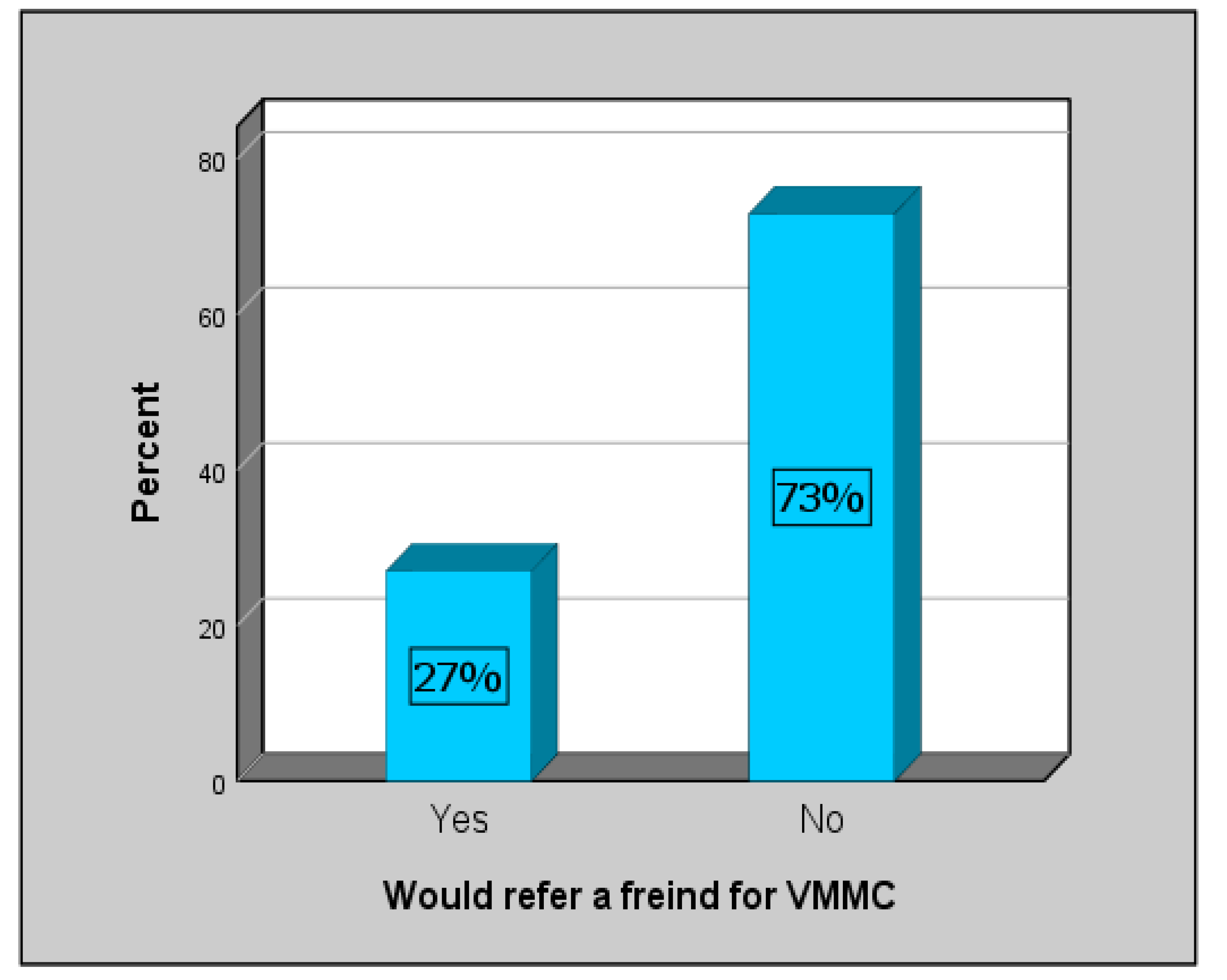

Only 27% of the respondents would refer a friend for VMMC and the rest (73%) would not (

Figure 4).

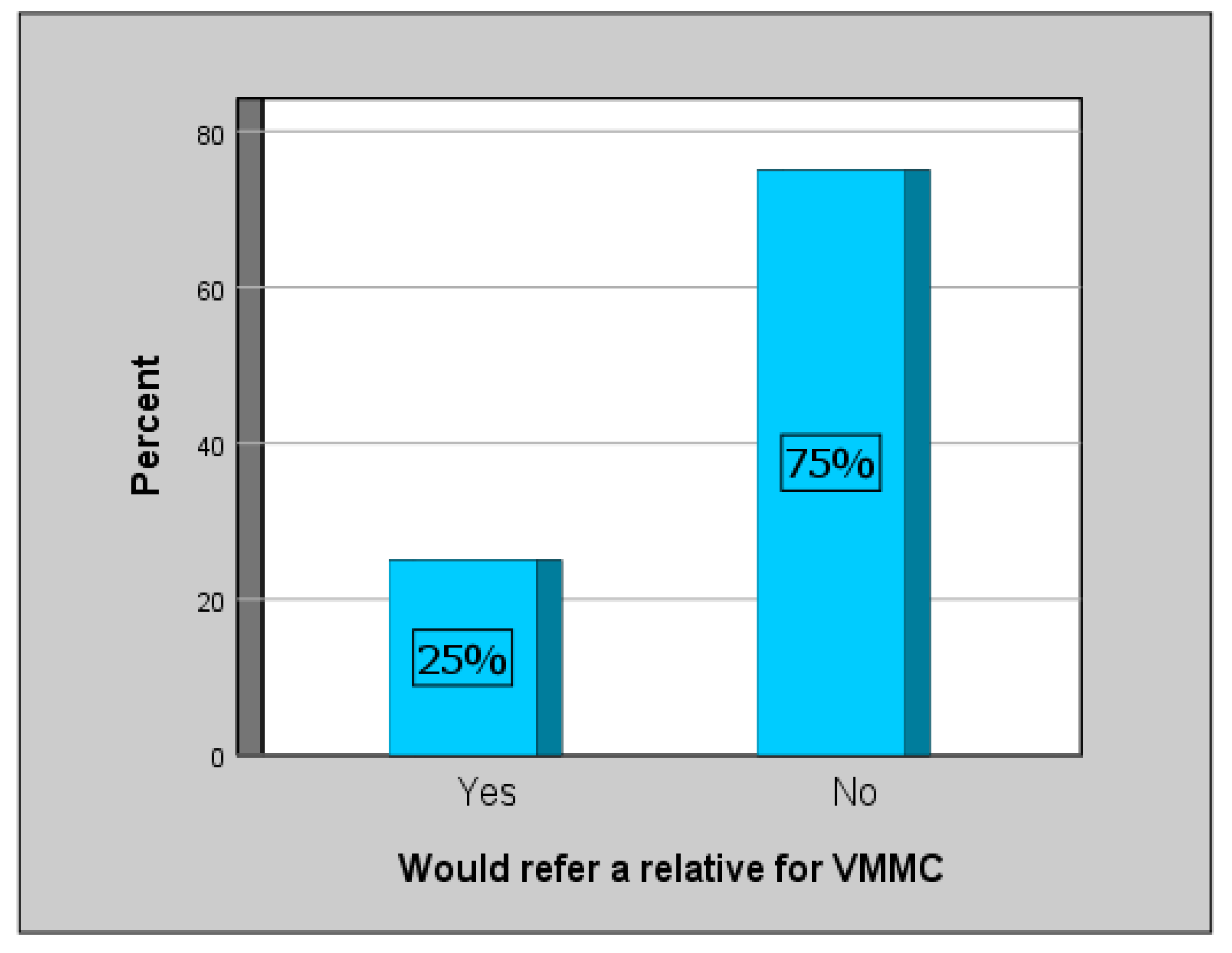

In addition, only 25% of the respondents would refer a relative for VMMC and 75% would not (

Figure 5).

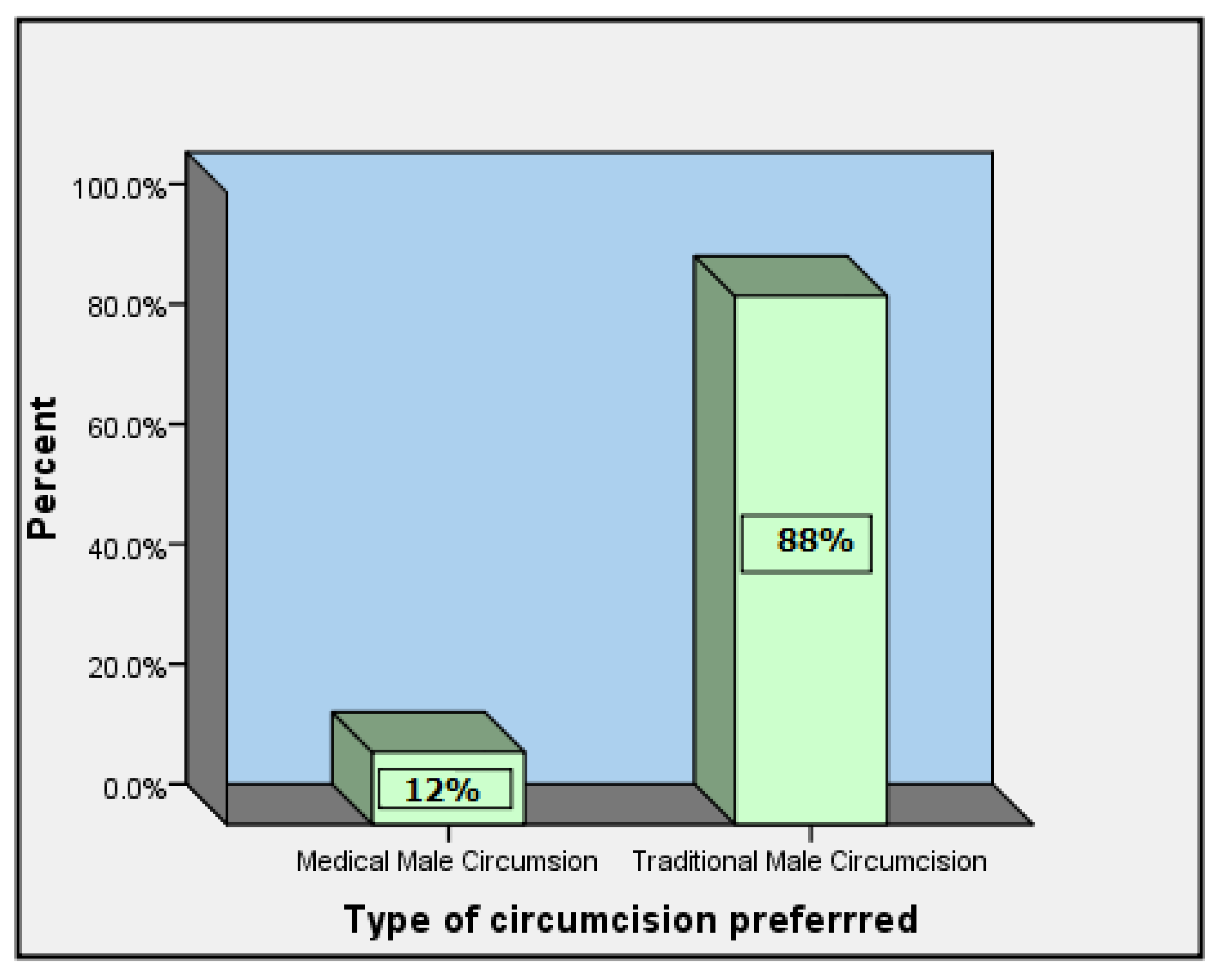

Compared to VMMC, most respondents (88%) preferred TMC (

Figure 6).

3.7. Factors Influencing the Acceptability of VMMC.

Factors influencing the acceptability of VMMC were assessed and are shown in

Table 6. Acceptability of VMMC was significantly associated with the following factors: the suggestion that VMMC reduced the risk of HIV infection among males (p=0.026) and among females (p=0.012); personal acceptance to undergo VMMC (p=0.001); acceptability of parents (p=0.034) and family members (p=0.005); acceptability of female friends (p=0.015) and female schoolmates (p=0.017); accepting to refer a friend (p<0.001) and a relative (p<0.001).

The acceptability of VMMC was not statistically associated with any socio-demographic characteristics (

Table 7).

3.8. Independent Factors Associated with Acceptability of VMMC

Bivariate associations of selected factors influencing the acceptability of VMMC (

Table 8).

Table 8 presents the bivariate associations of VMMC. Those participants who would consider undergoing VMMC were 16 times more likely to accept VMMC and this was statistically significant (OR= 16.0; p=0.001). Other participants who were significantly likely to accept VMMC are those who would refer a relative for VMMC (OR = 13.5; p-value <0.001), those who thought VMMC reduced the risk of HIV among females (OR = 5.1; p-value = 0.011) and those who thought that female friends would not discourage VMMC (OR = 4.8; p-value = 0.015).

4. Discussion

Male circumcision is associated with a reduction in risk of HIV/AIDS and STI transmission among males [

20]. VMMC has been reported to be much safer than TMC as it is associated with fewer complications that could range from local sepsis, amputation of penis, to more global complications and even death. This study provides a good basis for large scale studies on the understanding of socio-demographic factors that affect uptake of VMMC and can be used to generate hypotheses for future studies. In addition, more directed and structured interventions can be used as this study also explores the best medium of communication or marketing for the population.

This study is unique in that it doesn’t only address the research paucity in this area but has comprehensively sought to explore the perceptions, practices, and knowledge of VMMC among senior high school learners in a high HIV burden rural population that practices TMC as a cultural norm. The population did not have adequate knowledge about VMMC, did not accept it, would not recommend it for a friend or relative and mostly relied on television and radio for information. Educational strategies should emphasise that VMMC is not there to replace traditional practices but rather to supplement cultural practices by performing the surgical procedure in a sterile and safe environment whilst living the traditional ritual of initiation untouched.

The study respondents were young males attending Grade 11 and 12 in a high school in South Africa’s Eastern Cape Province. There were slightly more Grade 12s (57%) than Grade 11s (43%). In total, 86% of the participants were almost equally spread between the ages of 18 and 20 years. The age group and current school Grade of the respondents suggests that they began school at around the age of seven years in accordance with the South African School Act of 1996 [

21]. Further consistent with literature, which describes a community that has a similar setting as the study sight as a highly homogenous community, is the fact that almost 72% of the population were Christian [

22].The higher proportion of individuals who did not know their father’s jobs (23%) compared to those who did not know their mother’s job’s (5%) could suggest a high proportion of learners who lived with only their mother as a primary caregiver. This is also consistent with statistics South Africa reports for the area which reported that it is almost 57.6% of females headed households in this study area [

18].

Radio and television were the most cited sources of information on VMMC as an HIV prevention intervention at 55% and 58% respectively. This resonates with findings by Spyrellis et al.[

23], Hatzold [

24] and Chikutsa [

25] who all previously reported that the primary source of information about VMMC in South Africa is the radio and television. Evidence-based approaches should be used to develop health promotion strategies and marketing using these media platforms.

Sources through which information could be obtained by face-to-face interactive sessions such as in the clinics, hospitals (due to lack of visibility of community health care workers), HIV/AIDS organisations or community events, were cited by a minority of respondents. These findings denote that there is a high level of awareness about VMMC but low level of education and empowerment which are the pillars of acceptability.

The present study established that the level of knowledge about VMMC was low. This could be indicative of lack of education and empowerment communication strategies. This is because of the sources through which they got information concerning VMMC.

Effective strategies for improving knowledge are integrative and should monitor the competencies of the individuals who deliver the information on TV or Radio. Such strategies should also place emphasis on the quality of the VMMC content that is communicated to the public on all forms of media and public platforms and increase face-to-face sources of reliable information (e.g., community health workers, health promoters, school health nurses, etc.).

Bertrand [

26] and WHO [

27] reported that demand creation for mobilisation and motivation of men to access VMMC services should use targeted and age-specific communication strategies. Therefore, all communication strategies be it for awareness or educational purposes should provide clear information on the procedure, pre-test counselling; interpersonal attributes, and cost of the procedure [

27,

28]. The findings obtained from the present study could signify that the communication strategies that have been used to speed up the uptake of VMMC failed to provide accurate and adequate information.

To confirm the above, findings from this study show that the respondents knew that VMMC was different from TMC, that VMMC is safer when it is done according to protocol, and that there were complications related to VMMC. However, most of them were not knowledgeable about who performs the procedure and where the procedure was done. The findings also showed that the respondents had low levels of knowledge about VMMC as an HIV prevention intervention and when naming complications related to VMMC. These findings further show a lack of trustworthy information about VMMC.

Most participants (88%) preferred TMC to VMMC. These participants who preferred TMC supposedly due to social expectation for every male to go through the circumcision process the traditional way. This low level of VMMC acceptability could be because of the cultural and social ties of TMC. It is believed that AmaXhosa men who are not circumcised traditionally cannot be accepted as men [

29]. The respondents noted that they would not undergo VMMC. They would also not recommend a friend or relative to undergo VMMC [

30]. Peltzer et al. [

30] also noted that rejection of VMMC is influenced by the number of factors such as equipment used before and after the procedure, as well as the overall context for and meaning of the surgery (for HIV prevention and health, compared with a rite of passage to manhood). They (participants from this study) also confirmed that their parents, family members, peers (male friends, female friends, male school mates, female school mates), and community members would not allow them to undergo VMMC as an HIV prevention intervention. The low level of acceptability could also be because of the gap in knowledge on the health benefits of VMMC.

These findings contradict findings reported by Peltzer and Mlambo, and Milford [

31,

32].They documented a high level of acceptability of VMMC among Black African and Coloured population from both rural and urban areas from nine provinces in South Africa [

31,

32].

Furthermore, the evidence discovered from independent factors associated with acceptability of VMMC revealed that VMMC is gaining less acceptance as there are only few participants (10/31) who agree to undergo VMMC and 2/69 did not agree. Westercamp and Bailey [

33] recorded quite a few factors that influence the non-acceptability of VMMC such as pains, culture and religion, complications, and adverse effects. Some participants from study by Ngalande et al. [

34] recognised the need to pay for circumcision services because a free circumcision was viewed as being of potentially poor quality.

Despite efforts to minimise them, this study had some limitations. Participants were not asked to state reasons why they preferred the type of circumcision they chose over the other. However, this will be a subject of future studies as the objective of this study was to merely determine acceptability of VMMC. The circumcision status of the respondent was not determined. Evidence of whether these respondents have been circumcised (TMC or VMMC) or not could possibly provide added knowledge on the extent of the problem. It could have been great to classify the respondents as circumcised or uncircumcised, and if circumcised stratified by the type of circumcision. As this was a quantitative study, it was not possible to go in-depth into the reasons for the low level of knowledge and poor acceptability. The study sample was extracted from one rural high school and two grades, findings cannot therefore be generalised to all other rural males in the area. Notwithstanding, this study has been able to ascertain that learners in this high school have different levels of knowledge and acceptability. Future research needs to be undertaken to explore if this issue is not widespread and how the knowledge gaps could be closed.

5. Conclusions

Respondents demonstrated that they had a good understanding that VMMC is different from TMC. Though they had heard about VMMC, they had poor knowledge of how VMMC is done, who performs VMMC and the complications of VMMC. The major sources through which they had access to information seem to lack the education and empowerment elements that are needed to effectively educate people and enable them to take up VMMC as the preferred method for circumcision.

Most respondents demonstrated a low acceptability of VMMC. Only a small percentage of respondents had a positive attitude towards VMMC. Socio-economic characteristics that influence acceptability of VMMC was the employment status of mother. When mothers are formally employed, there is low acceptability of VMMC. Evidence-based strategies need to be established to improve learners’ knowledge and improve acceptability of VMMC.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Annexure 1: Questionnaire; Annexure 2: Access approvals obtained from the District Director of Education and the school Principal; Annexure 3: Ethics Committee of Walter Sisulu University, faculty of health sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (reference: 028/2018); Annexure 4: Parents provided assent for their children to participate if they were younger than 18 years; Annexure 5: The researcher was introduced to potential participants and consent forms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N. and L.G.; resources, W.C. and S.N.; methodology, A.N. and S.A.M.; formal analysis, S.A.M. and L.G.; data collection, L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G.; writing—review and editing, L.G., K.M., W.C., S.N, S.A.M., and A.N.; supervision, A.N and S.A.M.; project administration, K.M.; funding acquisition, W.C. and S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Walter Sisulu University, faculty of health sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (reference: 028/2018). Access approvals were obtained from the District Director of Education and the school Principal (Annexure 2).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Parents provided assent for their children to participate if they were younger than 18 years (Annexure 4). The researcher was introduced to potential participants and consent forms (Annexure 5) were distributed to learners. Each learner’s participation was voluntary, confidentiality was maintained, and they were informed that there would be no direct financial or non-financial incentives to them if they participated. Learners were also assured that their refusal to participate would not jeorpadise their standing or record in the school.

Data Availability Statement

All data reported are available from L.G. upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The Department of Education District Director (Mthatha Region), for granting permission to carry out the study at Libode. The school management and the learners from where the study was conducted.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mhangara Taremerezwa. Knowledge and acceptance of male circumcision as an HIV prevention procedure among plantation workers at Border Limited, Zimbabwe. University of Stellenbosch. 2011.

- Mokal N, Chavan N. Modified safe technique for circumcision. Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery. 2008, 41, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, D. Ritual male circumcision: a brief history. Journal-Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 2005, 35, 279. [Google Scholar]

- Blank S, Brady M, Buerk E, Carlo W, Diekema D, Freedman A, et al. Male circumcision. Pediatrics. 2012, 130, e756–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris BJ, Eley C. Male circumcision: An appraisal of current instrumentation. Biomedical Engineering, University of Rijeka, Rijeka. 2011;315–54.

- World Health Organization(WHO). Strategies and approaches for male circumcision programming. WHO meeting report: 5-6 December 2006. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43783/9789241595865_eng.pdf;sequence=1. (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Nqeketo, A. XHOSA MALE CIRCUMCISION AT THE CROSSROADS: RESPONSES BY GOVERNMENT, TRADITIONAL AUTHORITIES AND COMMUNITIES TO CIRCUMCISION RELATED INJURIES AND DEATHS IN EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE. 2008.

- UNAIDS and WHO. Available online: https://hivpreventioncoalition.unaids.org/resources/unaids-and-who-progress-brief-voluntary-medical-male-circumcision-february-2021. (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- World Health Organisatiom, W. HIV and AIDS July fact sheets. 2012. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids. (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- World Health Organisation, W. MODELS TO INFORM FAST TRACKING VOLUNTARY MEDICAL MALE CIRCUMCISION IN HIV COMBINATION PREVENTION MALE CIRCUMCISION FOR HIV PREVENTION MODELS TO INFORM FAST TRACKING VOLUNTARY MEDICAL MALE CIRCUMCISION IN HIV COMBINATION PREVENTION. 2017. Available online: http://apps.who.int/. (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Spyrelis A, Frade S, Rech D, Taljaard D. Acceptability of early infant male circumcision in two South African communities. Johannesburg: Centre for HIV and AIDS Prevention Research. 2013.

- IAS 2017 IAS. Randomised controlled Trials of Circumcision as a preventative measure: HIV & AIDS Information: Male Circumcision 2009 & 2017. In: 9th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2017) in Paris.

- Wilcken A, Keil T, Dick B. Traditional male circumcision in eastern and southern Africa: a systematic review of prevalence and complications. Bull World Health Organ. 2010, 88, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyembezi, A. Content analysis of newspaper coverage on injuries and deaths that are related to traditional male circumcision in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. 2015.

- Feni, L. Legislation in pipeline to curb illegal initiation schools. Daily Dispatch. 2014 Jul 11;2.

- Feni, L. 16 must undergo circumcision yet again. Daily Dispatch. 2015 Jun 30;1.

- Wilcken A, Keil T, Dick B. Traditional male circumcision in eastern and southern Africa: A systematic review of prevalence and complications. Bull World Health Organ. 2010, 88, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics South Africa. Provincial profile : census 2011. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-01-71/Report-03-01-712011.pdf. (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Maphill. Libode Maps. 2011. Available online: http://www.maphill.com/south-africa/eastern-cape/libode/. (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Jayathunge PHM, McBride WJH, MacLaren D, Kaldor J, Vallely A, Turville S. Male circumcision and HIV transmission; what do we know? Open AIDS J. 2014, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Basic Education S africa. School Admissions 2018 Admission of learners to public schools. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/Informationfor/ParentsandGuardians/SchoolAdmissions.aspx. (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Brittian AS, Lewin N, Norris SA. “You Must Know Where You Come From” South African Youths’ Perceptions of Religion in Time of Social Change. J Adolesc Res. 2013, 28, 642–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spyrelis A, Frade S, Rech D, Taljaard D. Acceptability of early infant male circumcision in two South African communities. Johannesburg: Centre for HIV and AIDS Prevention Research. 2013.

- Hatzold K, Mavhu W, Jasi P, Chatora K, Cowan FM, Taruberekera N, et al. Barriers and motivators to voluntary medical male circumcision uptake among different age groups of men in Zimbabwe: results from a mixed methods study. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e85051. [Google Scholar]

- Chikutsa A, Maharaj P. Support for voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) for HIV prevention among men and women in Zimbabwe. African Population Studies. 2015, 29, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand JT, Njeuhmeli E, Forsythe S, Mattison SK, Mahler H, Hankins CA. Voluntary medical male circumcision: a qualitative study exploring the challenges of costing demand creation in eastern and southern Africa. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e27562. [Google Scholar]

- WHO WHO, UNAIDS UNP on H. GENEVA. 2011. Joint trategic action framework to accelerate the scaleup of voluntary male medical circumcision for HIV prevention in Eastern and Southern Africa, 2012-2016. Available online: https://files.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/JC2251_Action_Framework_circumcision_en.pdf. (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- USAID USA for ID. Technical Brief. 2012. Voluntary Male Medical Circumcision (VMMC) for HIV prevention. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/global-health/health-areas/hiv-and-aids/technical-areas/accelerating-scale-voluntary-medical-male. (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Douglas M, Nyembezi A. Challenges facing traditional male circumcision in the Eastern Cape. Human Sciences Research Council. 2015, 1, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Nqeketo A, Petros G, Kanta X. Traditional circumcision during manhood initiation rituals in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: a pre-post intervention evaluation. BMC Public Health. 2008, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Mlambo M. Prevalence and acceptability of male circumcision among young men in South Africa. Studies on Ethno-medicine. 2012, 6, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milford C, Smit JA, Beksinska ME, Ramkissoon A. “There’s evidence that this really works and anything that works is good”: views on the introduction of medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2012, 24, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngalande RC, Levy J, Kapondo CPN, Bailey RC. Acceptability of male circumcision for prevention of HIV infection in Malawi. AIDS Behav. 2006, 10, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngalande RC, Levy J, Kapondo CPN, Bailey RC. Acceptability of male circumcision for prevention of HIV infection in Malawi. AIDS Behav. 2006, 10, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).