1. Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a lifelong, non-progressive disorder affecting movement and posture due to damage to the central nervous system. Children with CP usually experience musculoskeletal complications, impaired selective motor control, and poor balance affecting their gross motor function and activities of daily living [

1]. Moreover, owing to the nature of CP, which is permanent but changeable depending on variables such as growth, the effective management of complications could be essential. Thus, the importance of providing adequate rehabilitation and exercise according to the life cycle cannot be overemphasized [

2].

Various rehabilitation treatments such as physical therapy have been provided for children with CP. However, with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, access to facility-based treatment became limited. This caused challenges in health delivery systems and increased the demand for home-based programs and related digital information [

3,

4,

5]. Nowadays, people commonly use Internet sources to find and share information. To this end, YouTube, a well-known video-sharing site, is being utilized to address medical information. Reportedly, 43% of YouTube users get information about treatment and medical procedures [

6]. Furthermore, patients with chronic conditions often depend on Internet-based resources. According to surveys, 75% of patients were affected by the knowledge they acquired from the Internet in making decisions on treating their condition. This highlights the potential of YouTube as a platform for sharing health-related information [

7].

Despite the practicality of easily obtaining a lot of information, a risk of inaccuracy arises, as anyone can post on this platform, unlike scientific literature that requires peer-review processes. Previous studies have found that approximately 16–30% of informational videos related to health conditions on YouTube contained misleading information or were of low quality [

6]. Considering their potential impact on children with CP, the quality of content uploaded on YouTube must be evaluated. Consequently, this study aims to analyze YouTube-based therapeutic content for children with CP, focusing on the qualitative and quantitative aspects of the videos and therapeutic programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Video Selection Strategy

The keyword search was conducted on January 12, 2024, using the keywords for neuromotor therapy or exercise for CP as follows: “cerebral palsy + exercise,” “cerebral palsy + physical therapy,” “cerebral palsy + physiotherapy,” “cerebral palsy + rehabilitation,” “cerebral palsy + sensorimotor therapy + rood,” “cerebral palsy + voita therapy,” “cerebral palsy + sensoryintegration + ayres,” “cerebral palsy + patterning therapy + doman-delacato,” and “cerebral palsy + neurodevelopmental treatment + bobath.” A Python-based crawling technique was used to search all relevant videos on YouTube. Exclusion criteria included videos that were duplicates, unavailable, non-English or non-Korean, contained irrelevant content such as game suggestions, and created to promote a clinic. Additionally, videos lacking verbal instructions or explanations were deemed to be of poor quality and excluded, along with those with a duration of less than 60 seconds or longer than 30 minutes.

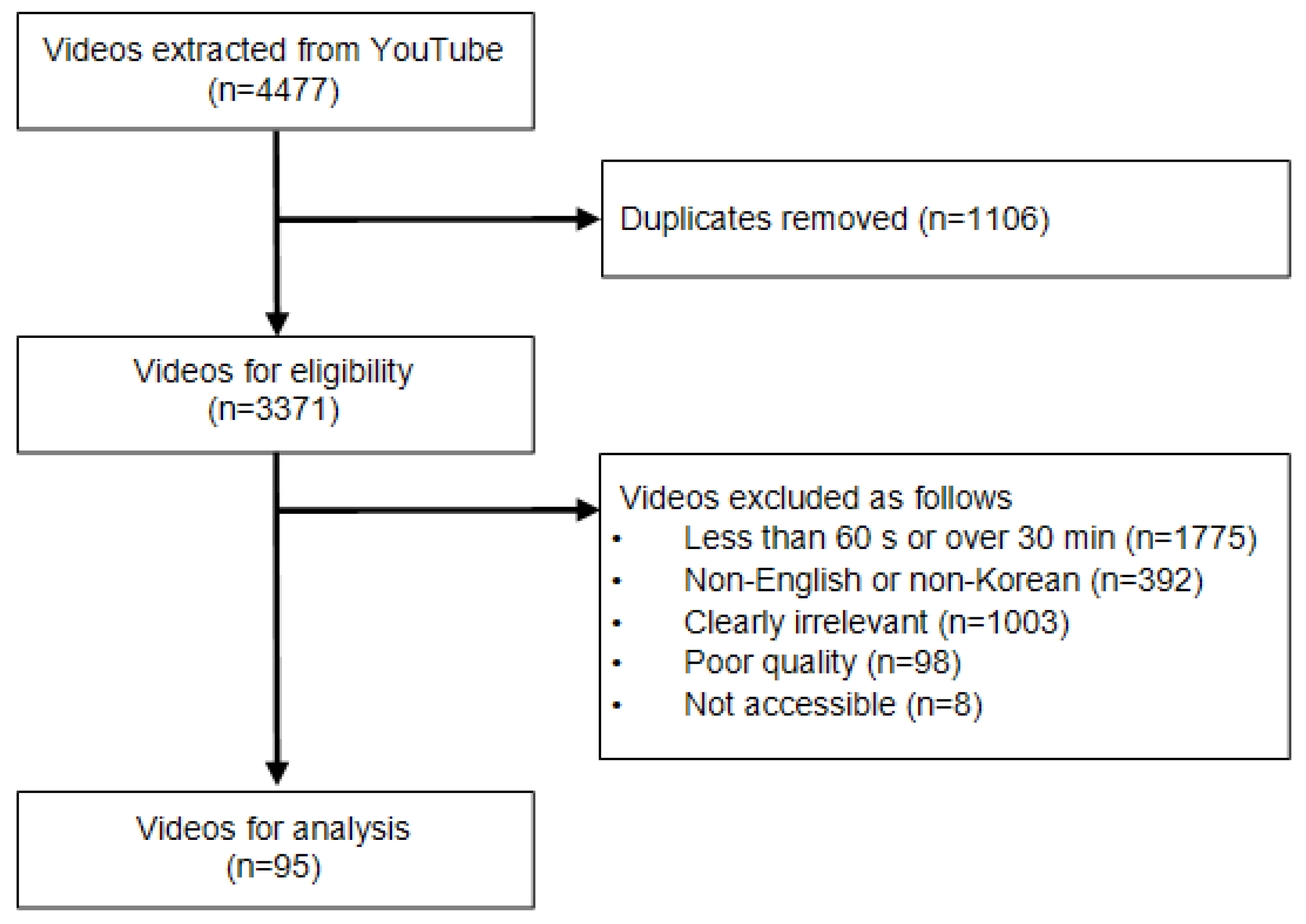

Figure 1 presents a flowchart outlining the video selection process. No ethical committee approval was necessary as this study exclusively utilized online videos without involving humans or animals.

2.2. Data Acquisition and Classification

Basic characteristics of videos, including the title, uniform resource locator, date uploaded, playtime, and information about uploader and therapeutic intervention, were collected. Uploaders were divided into two categories: health professionals, such as physical therapists, and non-professionals whose affiliations were unknown. Types of neuromotor therapy were categorized as “neurodevelopmental treatment (Bobath),” “sensorimotor approach to treatment (Rood),” “sensory integration approach (Ayres),” “Vojta approach,” and “patterning therapy (Doman-Delacato),” based on a previous review of a neuromotor therapy approach to CP [

8]. Types of exercise were categorized based on the guidelines of American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) for chronic disability [

9] as follows: “aerobic,” “strengthening,” “flexibility,” “warm-up and cool-down,” and “physical functioning exercise.” For classifications of neuromotor therapy and exercises, if two or more of the criteria were satisfied, it was classified as “mixed type.” If no criteria were satisfied, it was categorized as “unclassified type.”

Two researchers (YD and YO) evaluated all the videos included in this study according to the following three domains: popularity of video, quality of video content, and quality of therapeutic programs. When there were discrepancies between the two evaluators, a third researcher (JH) intervened, and the differences were discussed until consensus was attained. All researchers had more than five years of experience in physical therapy or pediatric rehabilitation.

2.2.1. Popularity-Related Parameters of Videos

Popularity-related information, such as the number of likes, dislikes, and total views, was collected. Moreover, the view ratio and video power index (VPI), representing the video’s popularity, was calculated through the following equation [

10].

2.2.2. Assessment Tools for Quality of Video Content

A modified DISCERN (mDISCERN) tool and Global Quality Scale (GQS) were used to assess the quality of the informational videos. Both tools are commonly used to assess the content quality of YouTube videos [

6]. mDISCERN comprises five items: “Clarity of aim,” “reliability of information sources,” “balanced and unbiased information,” “listing of additional information,” and “mention of uncertainty or controversy.” These were rated on a two-point scale in this study to evaluate the reliability of video content. One point was given when the video fulfilled the criteria of each item. A higher score indicates better reliability. A cutoff point of three out of the maximum of five points indicated significant reliability [

11,

12]. GQS is a subjective five-point scale designed to rate the flow and quality of online information [

6,

13]. Videos scoring 4–5 points were classified as being of a high quality, 3 points as moderate, and 1–2 points as low quality [

11].

2.2.3. Assessment Tools for Quality of Therapeutic Programs

The International Consensus on Therapeutic Exercise and Training (i-CONTENT) tool, Consensus on Therapeutic Exercise Training (CONTENT) scale, and Consensus on Exercising Reporting Template (CERT) were used to analyze the quality of therapeutic intervention in the videos [

14,

15,

16]. The i-CONTENT tool comprises seven items: “patient selection,” “dosage of the training program,” “type of training program,” “presence of qualified supervisor,” “type and timing of outcome assessment,” “safety of the training program,” and “adherence to the training program.” A rating scheme developed by Voorn et al. [

15] was used for the evaluation; it grouped videos into three categories, namely, as having low, some, or high risk of ineffectiveness.

The CONTENT scale comprises five critical areas: “patient eligibility,” “competencies and setting,” “rationale,” “content,” and “adherence” [

14,

17]. Each area was evaluated using a binary system, assigning 1 point for “yes” and 0 points for “no.” A program with 6 points or higher out of 9 was considered to have high therapeutic quality [

14,

17].

The CERT comprises 19 items in an extended version of the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist, which was utilized to examine the completeness of exercise descriptions. Each item is rated on a binary scale. A higher score indicates that the content includes more comprehensive information [

14,

16,

18].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) version 23.0. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation and a median with the interquartile range. The categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. A chi-squared test was performed to evaluate the association between the quality analysis tools and specific subgroups based on types of uploaders, therapeutic modalities, and exercises. Spearman’s rank correlation analyses were performed to verify the consistency between the assessment tools. The statistical significance of the p value was 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics and Quantitative Analysis of Video Content

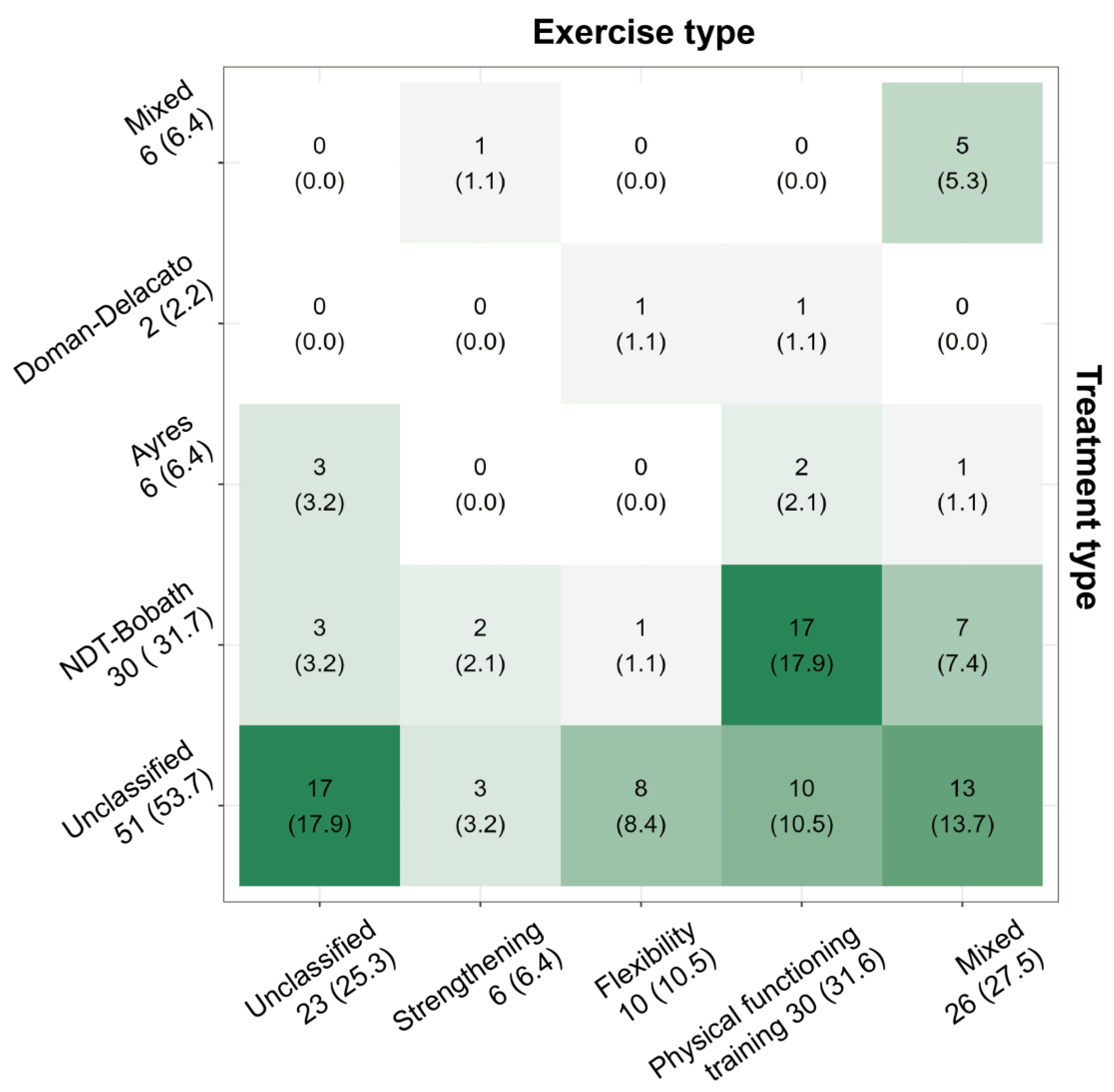

In total, 4,477 videos were collected via the Python-based crawling technique. Among them, 95 videos that met the inclusion criteria were evaluated in this study. The majority of videos were uploaded by health professionals (73, 76.8%). Regarding the types of neuromotor therapy, most videos were categorized as “unclassified” (51, 53.7%). Additionally, over 30% of the total videos (30, 31.6%) included the Bobath approach, while the Ayres (6, 6.3%), Doman-Delacato (2, 2.1%), and Rood and Vojta approaches (0, 0.0%) were represented in under 10%. Regarding exercise, the “unclassified type” accounted for only 25.3% of the videos, in contrast to the results for neuromotor therapy. The most common type was physical functioning exercise (30, 31.6%), followed by the mixed type (26, 27.5%), flexibility (10, 10.5%), strengthening (6, 6.4%), and warm-up and cool-down exercises (0, 0.0%). An overview of the general features of the included videos is shown in

Table 1. In the confusion matrix between the two classification methods, the most frequent instances were videos that could not be classified by either method and those based on the Bobath type as a physical functioning exercise (17, 17.9%) (

Figure 2).

3.2. Analysis of Qualitative Assessment for Video Content and Treatment Program

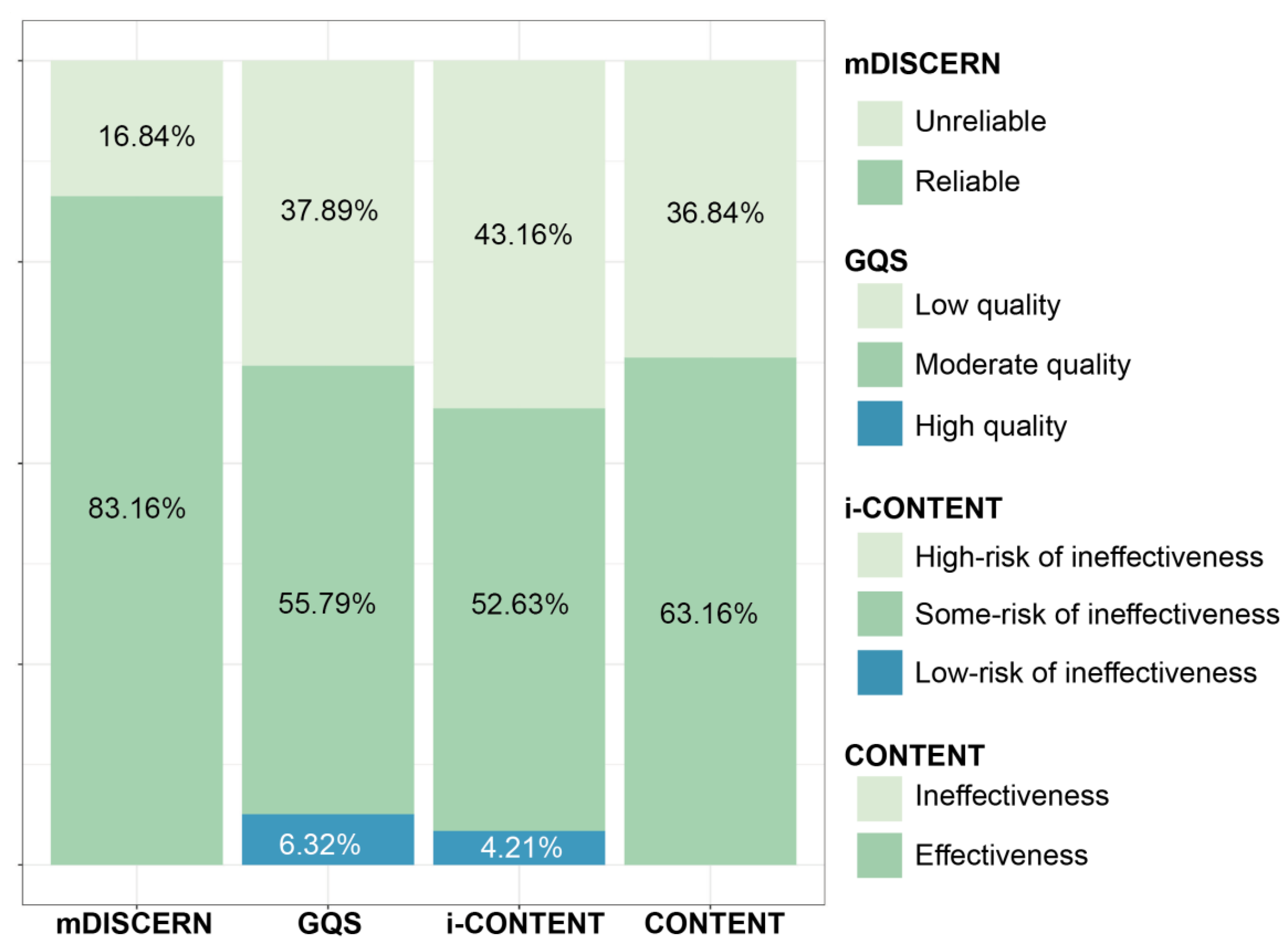

Table 2 provides the results of the evaluation of video content quality using mDISCERN and GQS. The mean mDISCERN score was 3.77 ± 0.12 out of 5, and 83.16% (n = 79) of the videos were classified as having reliable content (

Figure 3). The evaluation of each item reveals that over 75% of the videos demonstrated “clarity of aim,” “balanced and unbiased information,” “listing of additional information,” and “reliability of sources cited.” Furthermore, only 46.3% made “mention of uncertainty or controversy.”

The mean score of GQS was 2.64 ± 0.67 out of 5. Most content was evaluated as being of “moderate quality and flow” (55.8%) and “generally poor quality and flow’ (33.7%). This means that most content only contained some information, omitting crucial information, or contained crucial information on some aspects but not on others. By contrast, no content satisfied the criterion of having “excellent quality and flow.”

Table 3 presents the results of the therapeutic quality of programs based on i-CONTENT, CONTENT, and CERT. The mean score of i-CONTENT was 3.88 ± 0.11 out of 7. According to i-CONTENT, 43.16% of the videos were at a high risk of ineffectiveness, while 52.63% and 4.21% had some or a low risk of ineffectiveness, respectively (

Figure 3). Specifically, only two videos (2.1%) satisfied the criterion for the item “type and timing of outcome assessment.” Furthermore, items related to the safety (31, 32.6%) and dosage (34, 35.8%) of the program scored less than half the satisfaction rate, in contrast to other items related to patient selection, types of programs, and adherence.

The mean score of CONTENT was 6.00 ± 0.20 out of 9, and 63.16% (n = 60) of videos were classified as having effectiveness in terms of the quality of content (

Figure 3). Regarding competences and setting, most of the videos (96.8%) appeared to meet the criteria. However, for content-related items, less than 50% met the criteria, indicating an overall low level of fulfillment.

The mean score of CERT was 7.37 ± 0.33 out of 19. Per item, over 90% of the videos met the criterion of a “detailed explanation of each exercise to facilitate replication.” However, less than half met the criteria items related to exercise individualization (Items 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 13, 14), adverse effects (Item 11), set up (Items 12 and 15), and adherence monitoring method during the program (Item 16).

3.3. Relationship between the Qualitative Assessments of Video Content and Uploader Type

Based on uploader type, of the 95 videos, 73 were uploaded by health professionals and 22 by non-professionals.

Table 4 indicates the results of the video content quality evaluation for each tool for each type of uploader. Significant relationships were observed between the results of mDISCERN and GQS for the uploader types (p < 0.001, p = 0.001, respectively). Videos uploaded by health professionals exhibited a higher quality of video content. However, no relationships were observed between the types of uploaders and the results of the i-CONTENT and CONTENT tools.

3.4. Relationship between Quality Asessment and Ability to Classify Types of Therapeutic Interventions

Table 5 depicts the association between the quality analysis and classifiable video content based on the types of neuromotor therapy and exercise. All the videos aligning with the classification criteria were considered as “classified.” Divided by types of neuromotor therapy, no significant qualitative difference was observed between the two groups. However, when divided by exercise type, significant qualitative differences in the quality of the video and therapeutic program were observed.

3.5. Correlation between Qualitative and Quantitative Assessments of Video Content

Comparing popularity-related parameters including VPI and the view ratio with the quality analysis tools of video content and therapeutic intervention indicated no statistically significant correlation between all the quality assessment tools and popularity-related index (

Table 6).

3.6. Correlation between Qualitative Assessment Tools

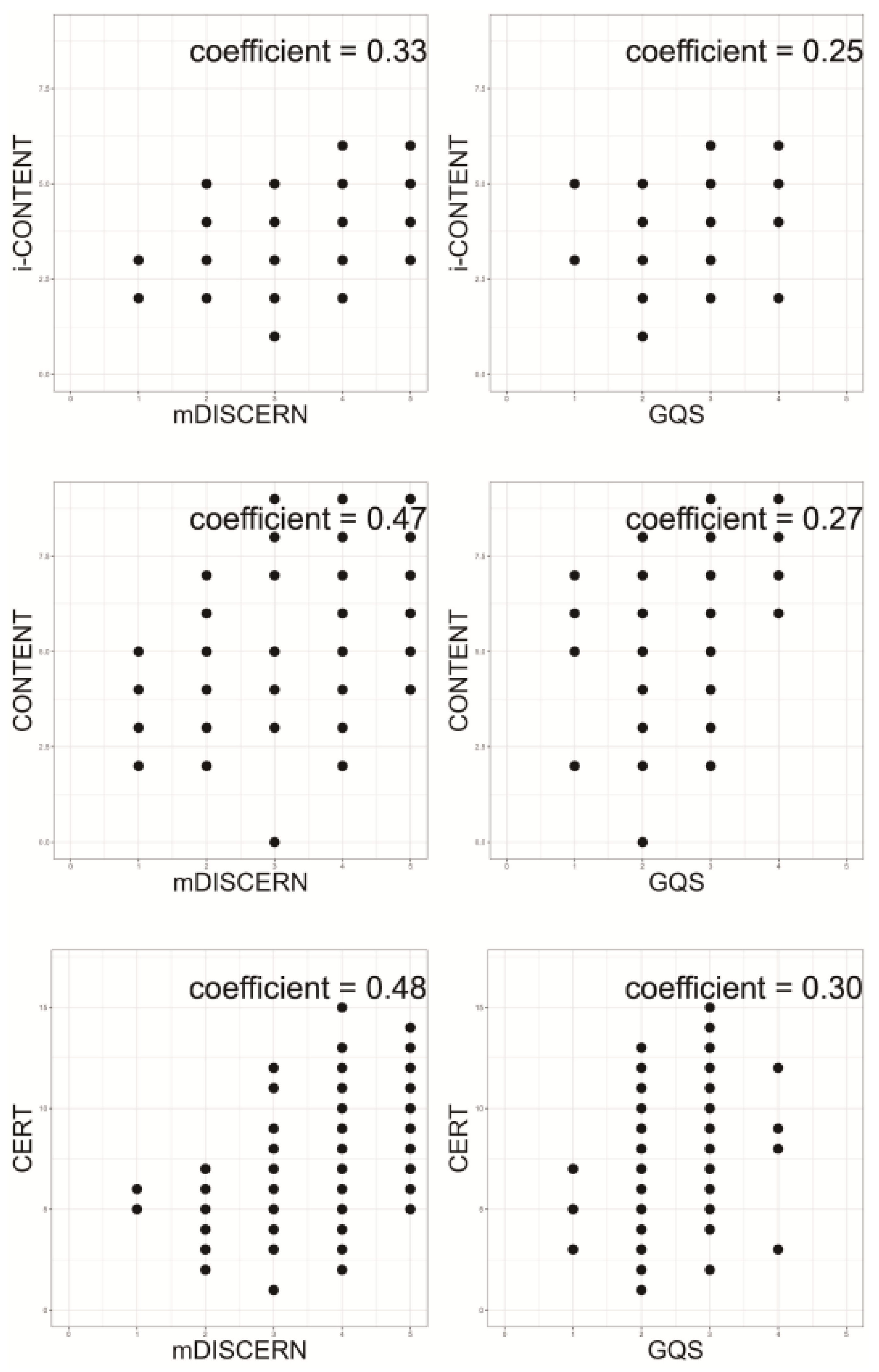

Spearman rank correlation analyses showed positive correlations between the evaluation tools (

Figure 4). There was moderate correlation between mDISCERN and CONTENT (rho = 0.466, p < 0.001) as well as CERT (rho = 0.483, p < 0.001), while a weak correlation was found with i-CONTENT (rho = 0.334, p < 0.001) (

Table 7). Finally, a weak correlation was found between GQS and other tools ( i-CONTENT: rho = 0.249, p = 0.015; CONTENT: rho = 0.270, p = 0.008; CERT: rho = 0.302, p = 0.003;

Table 7).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to quantitatively and qualitatively analyze web-based YouTube videos related to children with CP. Regarding the categorization by exercise type, physical functioning and mixed exercise accounted for the largest portion of videos in this study. No videos were related to aerobic and warm-up and cool-down exercises. According to the ACSM guidelines, these kinds of exercises are emphasized for individuals with CP [

9]. In the future, more content should be developed that considers these exercises and their safe application to pathological conditions. Regarding the types of neuromotor therapy, the largest portion of videos were of the “unclassified” type, indicating that, despite the development of many neuromotor therapeutic modalities for patients, a widespread introduction to these is lacking on current online platforms. Thus, as home-based exercise becomes increasingly important, videos on online platforms must be developed to introduce neuromotor therapies.

Furthermore, in the confusion matrix between the two types of classifications, 17.9% of the videos focused on Bobath therapy with physical functioning exercise, the highest proportion in this study. This observation aligns with the increasing research on and proven effectiveness of Bobath exercises and task-oriented training for patients with CP [

19,

20]. Nonetheless, the substantial number of videos that do not clearly fit into either classification (17.9% of all videos) underscores the necessity of higher-quality educational videos that differentiate various exercise and therapeutic techniques.

The qualitative evaluation of the videos indicates that more than half of them were of a moderate or higher quality. Regarding the item-specific satisfaction rates, most criteria in the mDISCERN tool achieved a satisfaction rate of over 75%. This high satisfaction rate suggests that most videos provided a detailed description of each action, effectively conveying the information and aim of the video through photos or video footage. However, only 46.3% of the videos satisfied the criteria for the item “mention of uncertainty or controversy.” This means that the videos included in this study tended to focus on effectiveness, not possible uncertainties or adverse effects. Moreover, the results from the GQS, which assesses information quality and the flow of information, in contrast to mDISCERN, showed that none of the videos met the criteria for “excellent quality and flow.” This is because few videos met the “good to excellent” standards for both criteria, and the YouTube-based videos included in this study were limited in terms of providing detailed “exercise information.” This indicates that, while YouTube is a popular platform for sharing exercise information, it may fall short in delivering comprehensive and well-structured educational content. This is a typical limitation of YouTube content that often requires the quick delivery of information to maintain engagement, which may influence the quality of video content [

21].

The qualitative assessment of therapeutic programs classified 43.16% of videos for i-CONTENT and 36.84% for CONTENT as ineffective programs. The videos included in this study tended to focus on explaining the type of exercise being introduced, but did not cover other elements of the FITT (Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type) principle, [

22] an important method for prescribing exercise programs. Specifically, items such as “dosage of the training program” in i-CONTENT, content category-related items in CONTENT, and Items 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 13, and 14 in CERT were closely related to constructing the FITT model. Additionally, aspects related to outcome measurement during or after therapeutic intervention (“type and timing of outcome assessment” in i-CONTENT, Items 16a and 16b in CERT), descriptions of adverse events (“safety of the training program”’ in i-CONTENT, Question 11 in CERT), and basic setup of exercises (Questions 12 and 15) such as precautions and subject posture were significantly lacking.

In the comparative quality analysis between videos uploaded by health professionals and those uploaded by non-professionals, although the majority in this study were produced by health professionals, a significant difference was observed only in video quality. No significant difference was found in therapeutic content quality. This implies that even videos produced by health professionals did not create disease-specific content for therapeutic interventions targeting children with CP. Therefore, this should be considered in future video production.

Furthermore, videos that could be classified by exercise type showed significant differences in the therapeutic qualitative evaluation compared with unclassifiable videos. By contrast, there was no statistically significant difference in quality and between groups based on classifiability based on neuromotor therapy. This indicates the video- and therapeutic-quality evaluation tools used in this study may be insufficient for evaluating the rationale for therapeutic techniques for CP. Thus, there is a strong need for evaluation items related to this aspect.

No correlations were found between the results for the quality evaluation tools and popularity-related parameters. This indicates that the degree of popularity of the videos does not guarantee the qualitative aspect of therapeutic educational videos. Moreover, a statistically significant correlation was found between video and therapeutic quality evaluation tools. Here, the therapeutic quality evaluation tools and mDISCERN demonstrated a more significant correlation than the results of GQS. This result could be influenced by the relatively large standard deviation of the GQS score compared with that of mDISCERN.

Finally, this study had several limitations. First, the sample of our study was relatively small to analyze quality comprehensively. Second, the treatment program assessment tools used in this study were originally designed to evaluate in-person treatment programs, Thus, they contained several elements that were not appropriate for assessing online treatment programs. There is a need to develop a new evaluation tool suitable for assessing video programs, which can comprehensively evaluate the quality of video content and treatment program and that is not limited to in-person programs. Third, there were significant differences in proportions between groups based on the types of neuromotor therapy and exercise, which rendered their statistical comparison difficult. Therefore, future studies should compare treatment modalities.

5. Conclusion

YouTube-based therapeutic videos for children with CP tend to be reliable in terms of video content and effective in the aspect of therapeutic programming. No correlations were found between popularity and quality of videos. However, the qualitative analysis indicated a lack of mentions of the uncertainty of the treatment principles in terms of video content. As a therapeutic program, we observed a lack of a detailed description of treatment that included aspects such as its intensity, frequency, time, setting, during- and post- outcome measurement, and safety. This tendency did not differ based on the uploader’s level of expertise. Moreover, videos classifiable by exercise type exhibited qualitative differences in therapeutic programs compared with unclassifiable videos, highlighting a lack of qualitative assessment tools for the neuromotor aspects of children with CP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.N.Y and H.J.T; Data curation, D.Y.R. and O.Y.J; Formal Analysis. D.Y.R. and H.J.T; Investigation, H.J.T; Methodology, H.J.T; Project administration, H.J.T, D.Y.R. and O.Y.J; Resources, H.J.T, Software, D.Y.R. and H.J.T; Supervision, K.N.Y; Validation, , H.J.T, D.Y.R. and O.Y.J;, Visualization, H.J.T; Writing – original draft, H.J.T, D.Y.R. and O.Y.J; Writing – review & editing, H.J.T

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kerr, C.; McDowell, B.; McDonough, S. The relationship between gross motor function and participation restriction in children with cerebral palsy: an exploratory analysis. Child Care Health Dev 2007, 33, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Rha, D.W. The Long-Term Outcome and Rehabilitative Approach of Intraventricular Hemorrhage at Preterm Birth. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2023, 66, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.B.; Mulpuri, N.; Cook, D.; Greenberg, M.; Shrader, M.W.; Sanborn, R.; Mulpuri, K.; Shore, B.J. The Impact of COVID-19 on Multidisciplinary Care Delivery to Children with Cerebral Palsy and Other Neuromuscular Complex Chronic Conditions. Children (Basel) 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristinziano, M.; Assenza, C.; Antenore, C.; Pellicciari, L.; Foti, C.; Morelli, D. Telerehabilitation during COVID-19 lockdown and gross motor function in cerebral palsy: an observational study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2022, 58, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadakia, S.; Stratton, C.; Wu, Y.; Feliciano, J.; Tuakli-Wosornu, Y.A. The Accessibility of YouTube Fitness Videos for Individuals Who Are Disabled Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Preliminary Application of a Text Analytics Approach. JMIR Form Res 2022, 6, e34176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtado, M.A.S.; Sousa Junior, R.R.; Soares, L.A.; Soares, B.A.; Mendonça, K.T.; Rosenbaum, P.; Oliveira, V.C.; Camargos, A.C.R.; Leite, H.R. Analysis of Informative Content on Cerebral Palsy Presented in Brazilian-Portuguese YouTube Videos. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 2022, 42, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madathil, K.C.; Rivera-Rodriguez, A.J.; Greenstein, J.S.; Gramopadhye, A.K. Healthcare information on YouTube: A systematic review. Health Informatics J 2015, 21, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifu, D.X. Braddom's Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation; Elsevier Health Sciences: 2015.

- Medicine, A.C.o.S.; Moore, G.E.; Durstine, J.L.; Painter, P.L. ACSM's Exercise Management for Persons With Chronic Diseases and Disabilities; Human Kinetics: 2016.

- Jung, M.J.; Seo, M.S. Assessment of reliability and information quality of YouTube videos about root canal treatment after 2016. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, C.W.; Bang, M.; Park, J.H.; Cho, H.E. Value of Online Videos as a Shoulder Injection Training Tool for Physicians and Usability of Current Video Evaluation Tools. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, C.H.; Lim, G.R.S.; Fong, W. Quality of English-language videos on YouTube as a source of information on systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Rheum Dis 2020, 23, 1636–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elangovan, S.; Kwan, Y.H.; Fong, W. The usefulness and validity of English-language videos on YouTube as an educational resource for spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2021, 40, 1567–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, D.; O’Neil, J.; Miron-Celis, M.; Brosseau, L. Content reporting in post-stroke therapeutic Circuit-Class exercise programs in randomized control trials. Topics in stroke rehabilitation 2019, 26, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorn, M.; Franssen, R.; Hoogeboom, T.; van Kampen-van den Boogaart, V.; Bootsma, G.; Bongers, B.; Janssen-Heijnen, M. Evidence base for exercise prehabilitation suggests favourable outcomes for patients undergoing surgery for non-small cell lung cancer despite being of low therapeutic quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2023, 49, 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattackal, T.-R.; Cavallo, S.; Brosseau, L.; Sivakumar, A.; Del Bel, M.J.; Dorion, M.; Ueffing, E.; Toupin-April, K. Assessing the reporting quality of physical activity programs in randomized controlled trials for the management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis using three standardized assessment tools. Pediatric Rheumatology 2020, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogeboom, T.J.; Oosting, E.; Vriezekolk, J.E.; Veenhof, C.; Siemonsma, P.C.; de Bie, R.A.; van den Ende, C.H.; van Meeteren, N.L. Therapeutic validity and effectiveness of preoperative exercise on functional recovery after joint replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012, 7, e38031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, S.C.; Dionne, C.E.; Underwood, M.; Buchbinder, R. Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT): Explanation and Elaboration Statement. Br J Sports Med 2016, 50, 1428–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, S.; Leksonowati, S.S.; Suriani, S.; Rustianto, D. Differences in the effectiveness of adding Bobath Exercise with (task-oriented training) on the balance of children with Cerebral Palsy. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach Research and Science 2024, 2, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Lee, D.; Ro, H. Effect of Task-oriented Training and Neurodevelopmental Treatment on the Sitting Posture in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 2011, 23, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, L.; Bansal, R.; Pruthi, N.; Khaskheli, M.B. Impact of Social Media Influencers on Customer Engagement and Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisner, C.; Colby, L.A.; Borstad, J. Editors. In Therapeutic Exercise: Foundations and Techniques, 7e; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, 2018.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).