1. Introduction

Cell membrane receptors are categorized into three major groups based on structural and functional criteria. These groups include receptors involved in cell adhesion, those facilitating ligand transportation to intracellular destinations, and those initiating intracellular signal transduction upon ligand activation (Iismaa and Shine, 1992). Among these, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) constitute one of the largest receptor families, with approximately 1000 different GPCRs identified in mammals. Numerous ligands, particularly peptide hormones, act via GPCRs, including significant effectors such as angiotensin II (AngII) and bradykinin (BK) in the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) and kallikrein-kinin system (KKS) (Oliveira et al., 2007; Peach and Dostal, 1990; Sandberg et al., 1994; Leeb-Lundberg et al., 2001, 2005). Recently our group examined the kinetics of spontaneous decomposition of glutamine-containing small GPCR’s CXCR chemokine heptapeptide generating a more hydrophobic pyroglutamic acid containing – derivative which by combining unique force atomic microscopy and infrared nanospectroscopy, revealed a typical amyloide-structure found in the known Alzheimer neurodegenerative disease (Ferreira et al., 2023).

Following the cloning of the AngII AT1 receptor, studies aimed to characterize its functional responses led to the identification of crucial regions in receptor-agonist interactions, including binding sites, agonist activation sites, G protein coupling sites, and internalization mechanisms (Correa et al., 2002; Hunyady et al., 1994; Monnot et al., 1996; Oliveira et al., 2007; Pignatari et al.,2006, Lopes et al., 2013). AngII, an octapeptide hormone, regulates blood pressure and electrolyte balance through its actions on the RAS via AT1 and AT2 receptors (Peach and Dostal, 1990; Tigerstedt and Bergman, 1898). Additionally, AngII is known to induce tachyphylaxis, and an alternative mechanistic model for this phenomenon has been already proposed by us (Barros et al., 2009). These receptors typically feature seven transmembrane helices and glycosylation sites in the extracellular N-terminal region (Oliveira et al., 2007, Lopes et al., 2013), with G protein coupling facilitating signal transduction across the cell membrane (Oliveira et al., 1994). Extensive research has aimed to elucidate the significance of individual residues and their impact on AngII’s structure and functional properties.

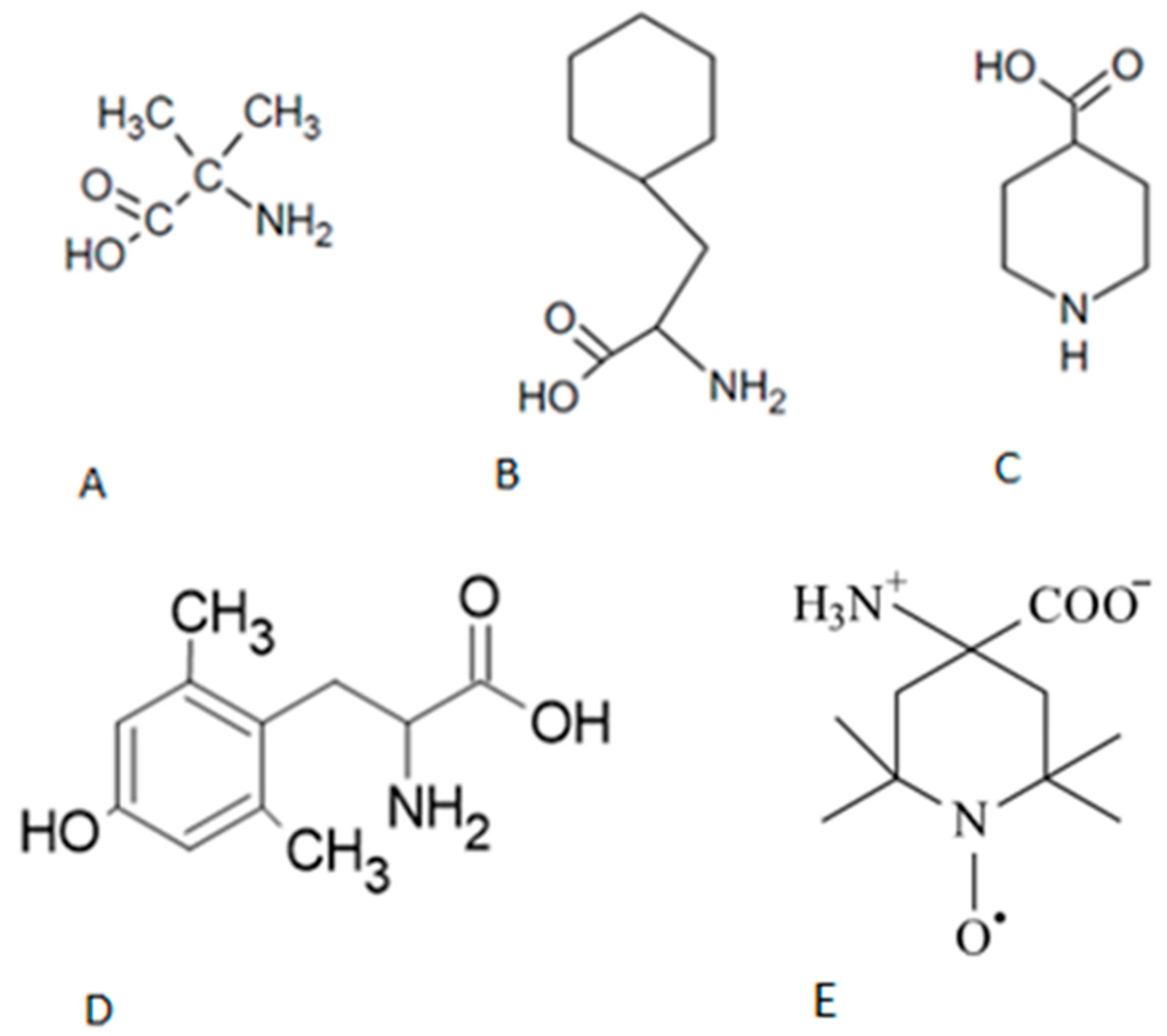

In this study, we focused on positions 3 and 4 of AngII. Peptides with unconventional substitutions, including Cyclohexylalanine (CHA), Isonipecotic Acid (IAP), Aminobutyric Acid (AIB), Dimethyltyrosine (DMT) and the spin label TOAC (2,2,6,6-tetramerhylpiperidine-1-oxyl-4-amine-4-caboboxylic acid) were synthesized for this purpose (see

Figure 1). This latter compound was introduced by our group (Nakaie et al., 1981, 1983, Marchetto et al., 1993, Schreier et al., 2012) as a mobility spin probe for monitoring dynamics of neighboring peptides and other macromolecules systems where it is associated.

All these peptide derivatives were then evaluated for their agonistic potency and structural characteristics using circular dichroism spectroscopy and computational modeling with Yasara software.

2. Results

Table 1 presents the activity results of the synthesized peptides. AIB

3-AngII and CHA

3-AngII showed activity, albeit with low potency. IAP

3-AngII and TOAC

3-AngII were inactive, while DMT

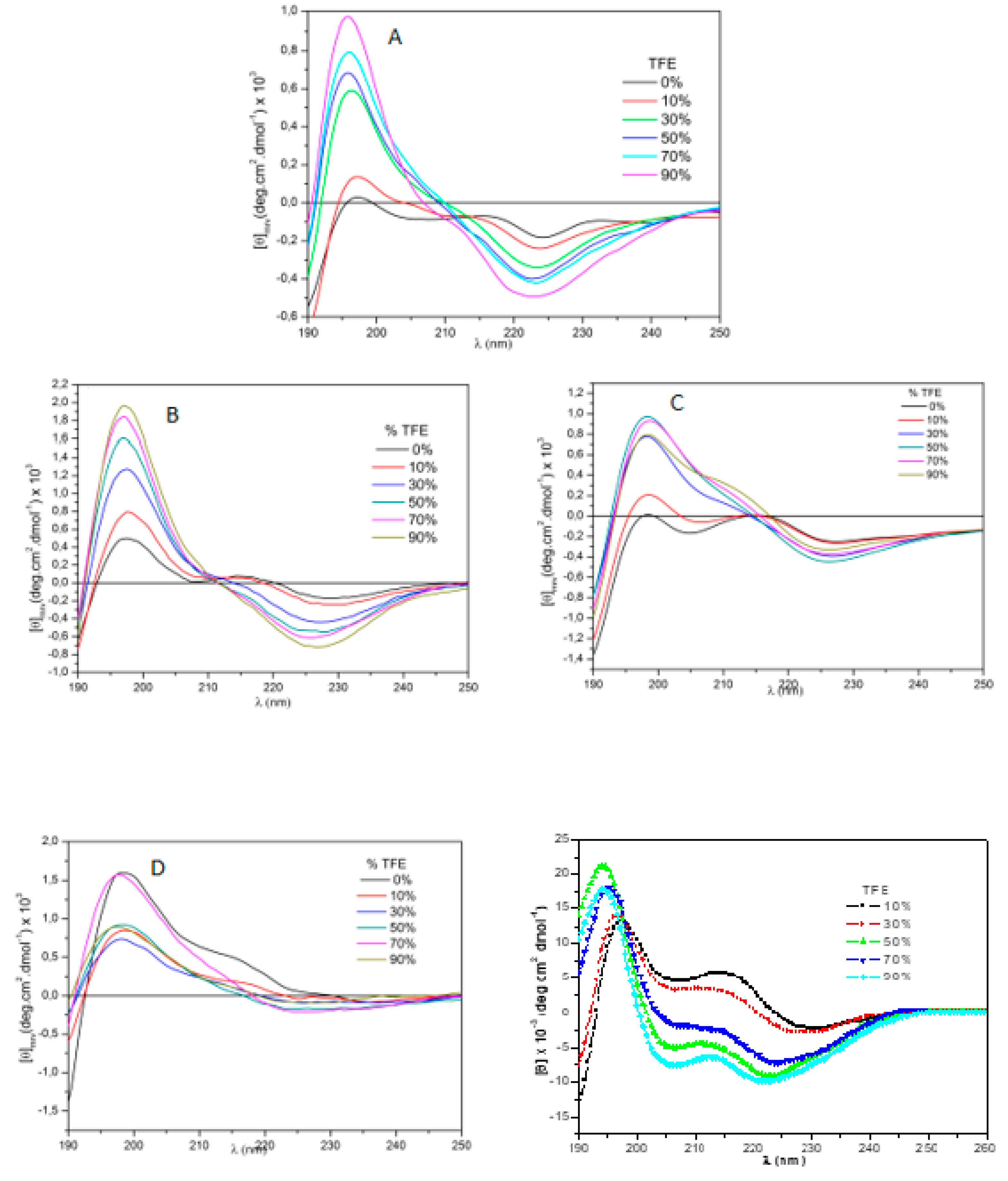

4-AngII retained 43.6% of AngII’s activity. Circular dichroism results for position 3 analogs are depicted in

Figure 2. A very folded structure, rather similar to that of IAP

3-AngI was observed with TOAC

3-AngII.

It is noteworthy that AngII exhibits a range of random structures in a polar environment, gradually transitioning towards an alpha helix structure with decreasing solution polarity. Both IAP

3-AngII and TOAC

3-AngII displayed reduced predisposition to random structures even in a polar environment with 0% TFE. Substituting tyrosine with DMT at position 4, as shown in

Figure 3, induced structures with more defined conformations.

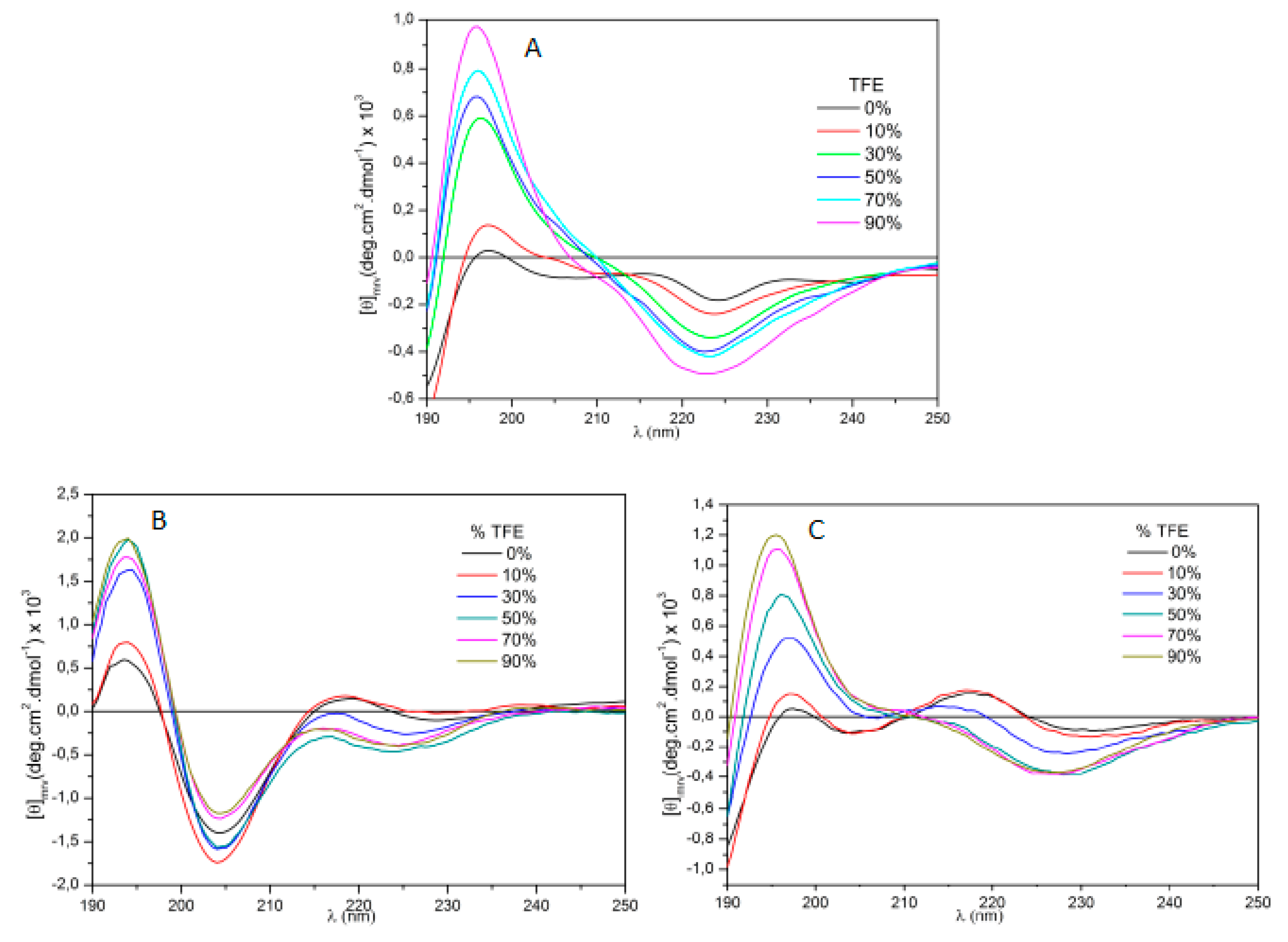

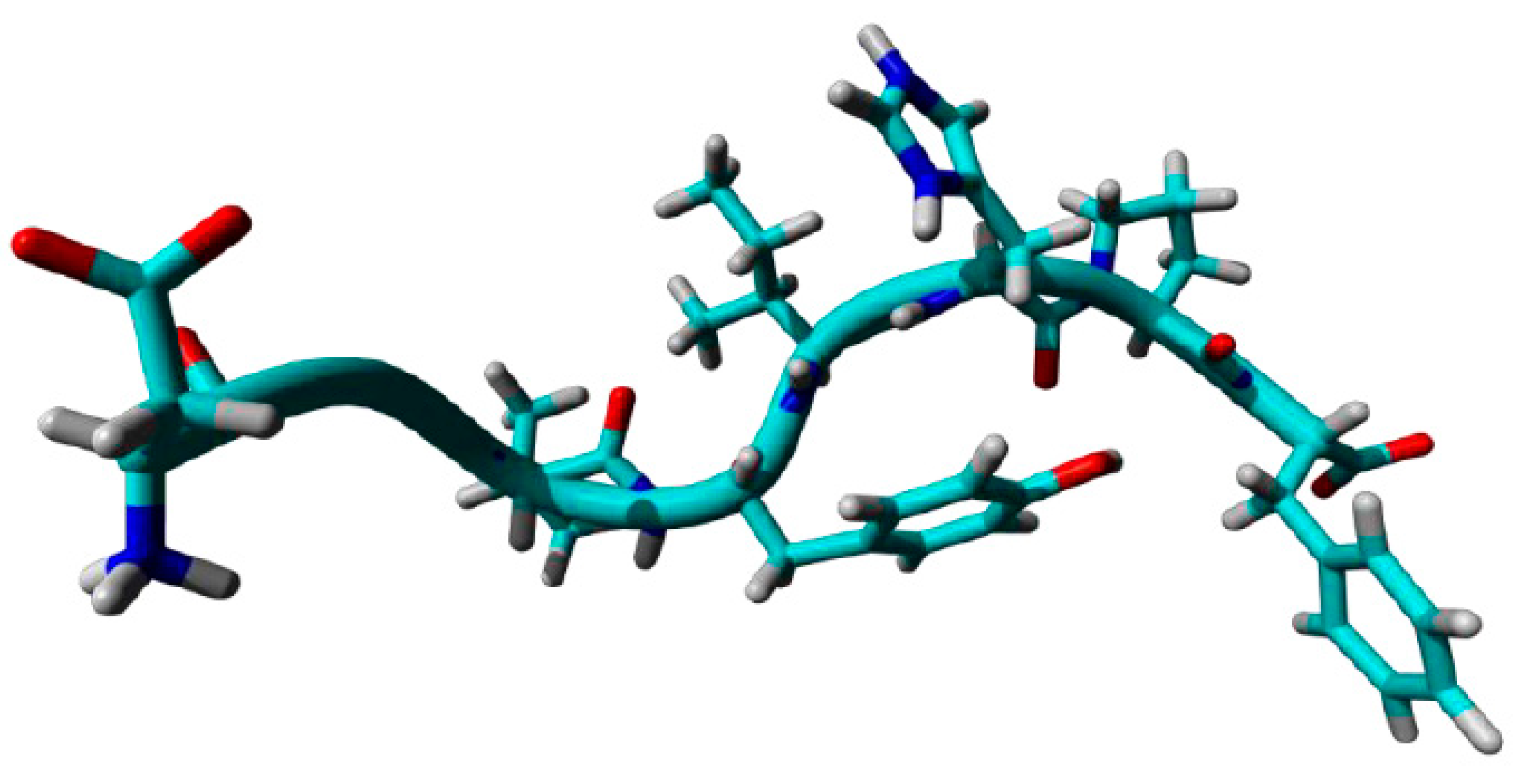

The results of molecular dynamics analyses regarding freedom degree are depicted in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. These images represent the superposition of multiple snapshots generated by molecular dynamics. In

Figure 4, all superimposed snapshots are aligned at position 3, with amino acids highlighted in yellow for clarity.

Concerning position 3, when the natural substitute valine is present (4A1 and 4A2), AngII displays high motility, capable of adopting various random conformations, albeit with some restrictive planes of movement. This suggests that valine retains significant flexibility compared to glycine, commonly regarded as the most flexible residue in protein sequences (Kawamura et al., 1996; Yan and Sun, 1997). However, the unnatural substituents studied (4B1 and 4B2 - AIB, 4C1 and 4C2 - CHA, 4D1 and 4D2 – IAP) reduce the freedom degree of their structures, likely causing constriction and twisting, thus limiting the conformational possibilities of AngII analogs. TOAC

3-AngII, as shown in

Figure 4E, also exhibits significant constriction in the molecule, restricting motility. The constriction induced by TOAC closely resembles that induced by IAP, as depicted in

Figure 4D.

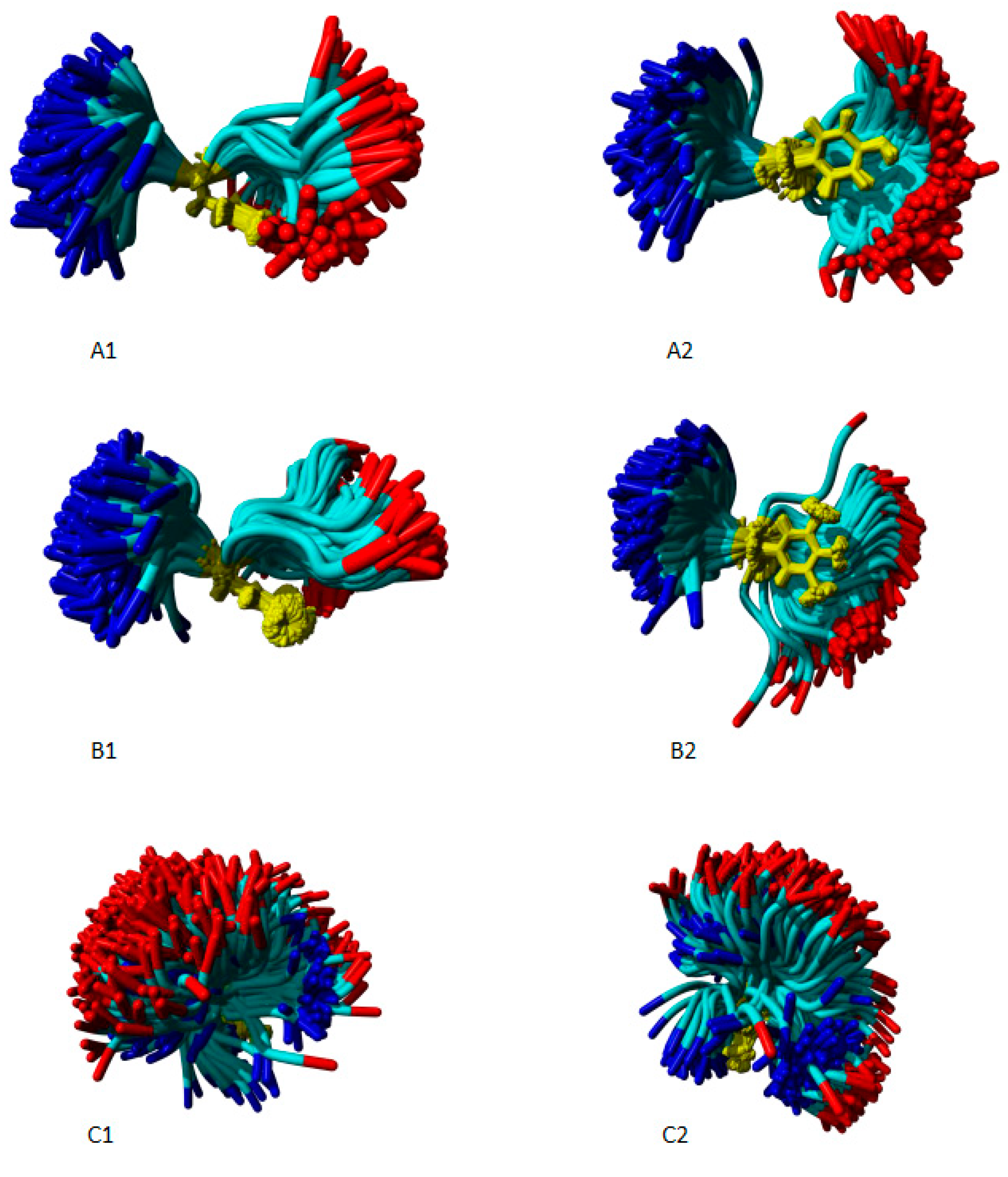

Regarding position 4, where tyrosine is the natural substitute, the results of computational dynamics are presented in

Figure 5. In AngII dynamics, tyrosine appears to directly influence molecule motility, with the tyrosine hydroxyl group directly linked to the carboxyterminal part of the molecule, thereby reducing the freedom degree of AngII. A similar observation is made for DMT

4-AngII; however, in this case, the freedom degree at position 4 seems to have been enhanced, enabling DMT

4-AngII to assume more conformations than AngII. In Figures 5C1 and 5C2, for Phe

4-AngII, the absence of the hydroxyl group significantly disrupts molecule conformations, drastically increasing the freedom degree of the molecule at position 4.

3. Discussion

In relation to position 3, the substituents AIB and CHA retained a modicum of pharmacological activity, albeit significantly lower than that of AngII. Circular dichroism studies reveal that, in comparison to the dichroism patterns of AngII, the other molecules exhibited more defined structures with fewer conformational variations when subjected to changes in the medium’s polarity.

Computational modeling was conducted using Yasara (Yet Another Scientific Artificial Reality Application) software to perform multiple molecular dynamics simulations. This software has been increasingly validated for its efficacy in constructing and predicting protein and peptide structures (Krieger and Vriend, 2015 Senthilkumar et al., 2017; Sharma et al., 2018) as well as in assessing biological activity (Aboye et al., 2016; Carstens et al., 2016; Chowdhury et al., 2020). Various methodologies for analyzing degrees of freedom in computationally modeled proteins and peptides have been documented (Bernhofer et al., 2021, Lincoff et al., 2016; Morrone et al., 2017; Prakash et al., 2018). This study introduces a novel approach for degree of freedom analysis. By superimposing molecular dynamics snapshots at different time points on specific amino acid positions of interest, these images provide a clear visual representation of the conformational movements permissible for these peptides at particular positions in the peptide chain.

An analysis of the molecular dynamics, as illustrated in

Figure 4, indicates that at position 3, the Angiotensin II (AngII) molecule exhibits a high degree of freedom, allowing it to bend in multiple directions. Such flexibility enables the molecule to assume a variety of random conformations in aqueous solutions. In contrast, AIB

3 and CHA3 show the emergence of a clamp-like structure. This clamping induces a fold in the AngII structure, consequently reducing its degree of freedom. Despite the formation of this clamp, it is observable that in Aib

3-AngII and Cha

3-AngII, the carboxyterminal region retains considerable flexibility, which may explain why Aib

3-AngII and Cha

3-AngII maintain some agonist activity.

Conversely, the IAP3-AngII analog exhibits the most pronounced clamping among the analogs, along with TOAC3-AngII, both of which demonstrate a substantial loss of carboxyterminal flexibility, resulting in inactivity. These findings suggest that position 3 plays a critical role in maintaining carboxyterminal flexibility. Substituents at position 3 that induce clamping reduce carboxyterminal freedom, thereby diminishing the biological activity of the analog. It is well-documented that the hydroxyl group of Phe8 is crucial for activating the AT1 receptor (Oliveira et al., 2007). An analog with a less flexible carboxyterminal region may encounter difficulty in accommodating itself successfully in the receptor activation site.

Figure 4 (B2 and E2) further illustrates the similarities between AIB

3-AngII and TOAC

3-AngII. The clamping in both peptide-derivatives is comparable to that caused by disubstituted glycine-type compounds such as AIB. The resemblance between these two compounds has been previously discussed in the literature (Schreier et al., 2004, 2012; Toniolo et al., 1998), where both are recognized for inducing folds in peptide structures.

Regarding position 4, the data show that DMT

4-AngII has 43,6% of Angiotensin II activity. Compared to the previously published data, Phe

4-AngII is inactive. Although it was already known that tyrosine hydroxyl plays an important role in AngII activity, these results intend to shed some light on the involved mechanisms. The superimposed snapshots presented in

Figure 5, show that tyrosine has some role in the possible conformations assumed by the AngII molecule. It is possible to notice that regarding position 4, the molecule freedom degree is more restricted.

When performing the dynamics with DMT

4, which has 2 methyls substituted in the benzene ring, we noticed that there was some impediment in interaction, generating a significantly greater freedom degree, thus its superimposed snapshots assume a more expanded structure. Analyzing molecular dynamics of Phe

4 (4C), we can see that AngII natural freedom degree restriction was utterly disrupted. These results indicate that the tyrosine hydroxyl determine the conformation of AngII molecules by interacting with molecule carboxy terminal end. By randomly isolating a molecule from the overlapping dynamics (see

Figure 6), it can be seen that the tyrosine hydroxyl is interacting directly with the terminal carboxy part of AngII, more specifically forming a hydrogen bond with the nitrogen of the amide group between Pro

7 and Phe

8.

4. Conclusions

Our study meticulously examined the impact of atypical substituents at positions 3 and 4 on the structure-function relationship of Angiotensin II (AngII). Substituents at position 3 that induce clamping reduce the flexibility of the carboxyterminal region, leading to diminished pharmacological potency. This observation underscores the pivotal role of position 3 in facilitating a flexible carboxyterminal region, which is crucial for the accommodation of the peptide within the AT1 receptor and subsequent activation. Conversely, for position 4, our findings indicate that an increased degree of freedom may correlate with a reduction in biological activity. The interaction between the hydroxyl group of tyrosine and the carboxyterminal region of AngII appears to significantly influence peptide conformation and receptor binding. Further investigation, particularly through molecular docking simulations, can provide deeper insights into this interaction and its impact on receptor activation.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Animals, General Preparations, and Peptides Potency In Vitro

The tests were conducted with ileum isolated from guinea pigs from the animal house facility of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), SP, Brazil. The Ethical Committee approved this study and all experimental animals use protocols were in accordance with current guidelines for the care of laboratory animals. The animals were kept at 21–23,8 C, with a standard diet, a 12:12 h light/dark cycle, and ad libitum access to food and water. Guinea-pigs of either sex, weighing 200–300 g, were killed by cervical dislocation and exsanguinations. The abdominal cavity was opened and the ileum removed and used in the pharmacological tests.

For determination of peptide potency, 20-cm part of the terminal ileum was removed and washed at room temperature in Tyrode’s solution (137 mM NaCl, 2.70 mM KCl, 1.40 mM CaCl2, 0.50 mM MgCl2, 12.0 mM NaHCO3, 0.40 mM NaH2PO4, and 5.60 mM D-glucose). Strips of 3-cm length were cut and mounted in chambers containing tyrode solution (5 ml), maintained at 378º C and bubbled with either air (pH 8.4) or a mixture of O2/CO2 (95%:5%; pH 7.4). The strips of guineapig ileum were kept under a 1-g tension. Tension readings by the analogs were measured with an isometric transducer F-60 (International Biomedical, Inc., Austin, TX, USA) and a potentiometric recorder (RB-102, Equipamentos Cientificos Brasil, São Paulo, SP, Brazil). The potency was then calculated as pD2s-log EC50, where EC50 is the concentration of the agonist that induced 50% of the maximum response (obtained by interpolation in log dose-response curves).

5.2. Drugs and Solutions

Resins and amino acid derivatives were purchased from Bachem (Torrance, CA, USA). All reagents fulfilled the ACS standards. AngII and all analogs were synthesized using solid phase method using the tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc) strategy (Barany e Merrifield 1980; Verlander 2001). 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl-4-amino-4carboxylic acid (TOAC)-bearing derivatives was an exception. In these cases, TOAC3-AngII was produced using the method previously described (Lopes et al. 2013; Marchetto et al., 1993; Nakaie et al. 2002). For Peptide purification, it was used a Waters 510 HPLC instrument using a Vydac C18 preparative column (22 mm internal diameter, 250 mm length, 70 A° pore size, 10 mm particle size). AngII was dissolved in either 5% or 20% acetic acid solution according to their solubility. The mixtures were then sonicated, centrifuged at 10 000 g and filtrated. The solutions were loaded onto the column and eluted with a linear gradient using the solvent systems A (H2O containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)) and B (60% acetonitrile in H2O containing 0.1% TFA). AngII (25–55% B) and the analogs (45–75% B) were eluted in a linear gradient in 90 min, with a flow rate of 10 mL/min and UV detection at 220 nm. The fractions were screened under an isocratic condition in a Chromolit C18 analytical column. Pure fractions were pooled, lyophilized, and characterized for homogeneity by analytical HPLC (Waters Associates, Milford, MA, USA) and mass spectrometry on RP-HPLC/MS (Micromass, Manchester, UK).

5.3. Circular Dichroism

The CD spectra were obtained in a Jasco model 810 spectropolarimeter in the range of 190-260 nm , using a circular quartz cell with 0.1 mm optical path. All peptides were at a concentration of the order of 10-4 mol.L -1. The spectra were collected with a response time of 8 seconds, acquisition speed 50 nm/min, step 0.2 nm and in 4 accumulations. In addition, disulfide bonds and aromatic amino acids ( Phe , Tyr and Trp ) contribute to bands in the 230 nm region (Purdie 1996).

In the present study, the device used was the Jasco J-810 at room temperature, under a nitrogen atmosphere. The spectra were obtained of peptide solutions of 10-4 mol.L 1 concentration , 0.02 mol.L-1 buffer phosphate, pH 7.0 and in aqueous solutions containing different percentages of TFE.

5.4. Molecular Dynamics

The models of the peptide structures were created in the Yasara program (Krieger et al., 2004, Krieger and Vriend, 2015) using the classic protein building tools from the program’s own amino acid database. In the case of non-amino acid compounds like AIB , CHA , IAP , DMT and TOAC, Glycine was used as a standard and atoms were added and removed until the most suitable structure was reached. As a particular case, TOAC required specific parameters / characteristics due to the presence of the unpaired electron in the nitroxide group of its structure, see

Figure 1. In this case, we apply specific guidelines suggested by the creators of the Yasara program , due to this structural feature of TOAC for the study of the molecular dynamics of peptides containing this paramagnetic marker.

After three-dimensional structure of each peptide sequence, we use pre-determined commands (macros) existing in the program and necessary to achieve the objective of evaluating the molecular dynamics of each peptide. Energy minimization macro, proceeded by the application of Molecular Dynamic macro was run in each analog. The programa assumed a density of 1 g. cm-3. Every 3 femtoseconds of simulation (one simulation step), the program updates the image of the molecule and every 12,500 simulation steps, the three - dimensional image of the molecule is recorded (a snapshot ). These snapshots contain the position and velocity of the atoms at that specific moment, with 14 nanoseconds being the simulation time chosen for all studies of the molecular dynamics of each peptide evaluated. The approximate running time of the dynamics of a compound with 14 nanoseconds with our equipment was in the range of 5 to 7 days.

At the end of this process, all snapshots are properly analyzed by the program that checks all the positions photographed during the simulation and calculates an average position of the molecule at the time of the simulation. The simulations are therefore all registered and we can extract from the program, the overlapping of all the recorded snapshots, but focusing on the visualization of the images in specific desired positions of the sequence. These superimposed snapshots therefore represent the sum of all possible conformations, in 14 nanoseconds of simulation, for the analog in question (degree of freedom) in that angle of view. In this case, eventually, to more accurately analyze a given region, one of the conformers that make up the overlapping structure can be isolated and studied individually. This was chosen, based on the visual analysis of the desired region. Recent work of our group has also applied computational approach for revealing the short sequence Ac-(2-7)-Ang-NH2 as a selective potential angeiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor (Silva et al., 2022).

5.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using the Student t-test for unpaired data. Arithmetic mean”standard deviation (SD) values and 95% confidence limits are given in

Table 1 and Table 2.

Institution Review Board Statements

not applicable.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Author Contributions

conceptualization, writing-review and edition, supervision (CRN), methodology, formal analysis, writing - original data preparation (AJB).

Funding

the research leading to those results has received funding (CRN) from São Paulo Research Funding FAPESP, under grants #21/04885-3. CRN is recipient of research fellowship from the Brazilian Council for Scientific Research CNPq; thank the Coordination from the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel CAPES for PhD fellowship (AJB). Special thanks to Caroline C. Silva, Marta G. Silva and Sinval E. G. Souza for the excepcional technical support for this project.

Informed consent Statement

not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

the data are included in the main manuscript and Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare that the research was conductd in the absence of any commercial or financial relationship that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Aboye, T.; Meeks, C.; Majumder, S.; Shekhtman, A.; Rodgers, K.; Camarero, J. Design of a MCoTI-based cyclotide with angiotensin (1-7)-like activity. Molecules 2016, 21, 152. [Google Scholar]

- Barany, G.; Merrifield. R. B. The Peptides, 1980, 2, 1-284, Gross, E , Meinhofer, J.(eds), Academic Press Inc., New York.

- Barros, A. J.; Ito, C. M.; Makino, E. N.; Cembranelli, F. A. M.; Moraes, F. C.; Souza, S. E. G.; Oliveira. L.; Shimuta, I. S.; Nakaie, C. R. Factors regulating tachyphylaxis triggered by N-terminal-modified angiotensin II analogs”. Biological Chemistry 2009, 390. https://www.degruyter.com/doi/10.1515/BC.2009.143.

- Bernhofer, M., Dallago, C.; Karl, T.; satagopam, V.; Heinzinger, M.; Littmann, M.; Olenyl, T.; Qiu, J.; Schütze, K.; Yachdav, G.; Ashkenazy, H.; Ben-Tal, N.; Bromberg, Y.; Goldberg, T.; Kajan, L.; O´Donoghue, S.; Sander, C,. Schafferhans, A.; Vriend, G.; Mirdita, M.; Gawron, P.; Gu, W.; Jarosz, Y.; Trefois, C.; Steinegger, M.; Schneider, R.; Bost, B. PredictProtein – Predictng protein structure and function for 29 years. Nucleic Acid Res. 2021, 49(W1):W540m. [CrossRef]

- Carstens, B.B,.; Swedberg, J.; Berecki, G.; Adams, D.J.; Craik, D.J.; Clark, R.J. Effects of linker sequence modifications on the structure, stability, and biological activity of a cyclic α-Conotoxin. Biopolymers 2016, 106, 864–75.

- Chowdhury, S.;M.; Talukder, S.A.; Khan, A.; M, Afrin, N.; Ali, M.A.; Islam, R.; Parves. R, Al Mamun, A.; Sufian, M.A.; Hossain, M.N.; Hossain, M.A.; Halim, M.A.; Antiviral peptides as promising therapeutics against SARS-CoV-2. J. Phys. Chem. 2020. 124, 9785–9792.

- Correa, S.A,; Zalcberg, H.; Han, S.W.;, Oliveira, L.; Costa-Neto, C.M.; Paiva, A.C.; Shimuta. S. I.; Aliphatic amino acids in helix VI of the AT1 receptor play a relevant role in agonist binding and activity. Regul. Pept. 2002 106 , 33–38.

- De Vivo, M.; Matteo, M.; Giovanni, B.; Cavalli, A. Role of molecular dynamics and related methods in drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 2016 59, 4035–4061. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M.M.L.; Souza, S.E.G.; Silva, C.C.; Souza, L. E. A.; Bicev, R. N.; Silva, E. R.; Nakaie, C. R.; Pyroglutamination-induced changes in the physicochemical features of a CXCR4 chemokine peptide: kinetic and structural snalysis. Biochemistry. 2023 5; 62, 2530-2540. [CrossRef]

- Hunyady, L., Baukal, A. J.; Balla, T.; Catt. K. J.; Independence of type I angiotensin II receptor endocytosis from G protein coupling and signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 24798–804.

- Iismaa, T.P., Shine, J.. G protein-coupled receptors;. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 1992. 4, 195–202.

- Inoue, I, Nakajima, T.; Williams, C. S.; Quackenbush, J.; Puryear, R.; Powers, M., Cheng, T.; Ludwig, E. H.; Sharma, A. M.,; Hata, A.; Jeunemaitre, X.; Lalouel, J. M.; A Nucleotide substitution in the promoter of human angiotensinogen is associated with essential hypertension and affects basal transcription in vitro. J. Clin. Invest. 1997. 99, 1786–97.

- Kawamura, S,; Kakuta, Y,; Tanaka, Ii.; Hikichi, K.; Kuhara. S.; Yamasaki. N.; Kimura, M. Glycine-15 in the bend between two α-helices can explain the thermostability of DNA binding protein HU from Bacillus Stearothermophilus. Biochemistry 1996 35, 1195–1200.

- Krieger, G.; Darden, T.; Nabuurs, S. B.; Finkelstein, A.; Vriend, G. Making optimal use of empirical energy functions: force-field parameterization in crystal space. Proteins 2004, 57, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, E.; Vriend. New Ways to Boost Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2015, 36, 996–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Leeb-Lundberg, L. M.; Fredrik, D. S.K .; Maria E. L.; Fathy, L. B.; The human B1 bradykinin receptor exhibits high ligand-independent, constitutive ctivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2001 276, 8785–892.

- Leeb-Lundberg, L.; M, Marceau. F,; Müller-Esterl W.; Pettibone, D.J.; Zuraw, B.L.; International union of pharmacology XLV. Classification of the inin receptor family: from molecular mecanism to pathophysiological consequences. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005.57, 27–77.

- Lincoff, J.; Sukanya, S., Head-Gordon, T. Comparing generalized fnsemble methods for sampling of systems with many degrees of freedom. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 145, 174107.

- Lopes, D. D. ; Vieira, R. F. F. ; Malavolta, L. ; Poletti, E. F., Shimuta, S. I. ; Paiva, A. C. M. ; Schreier, S. ; Oliveira, L. ; Nakaie, C. R Short peptide constructs mimic agonist sites of AT1R and BK receptors. Amino Acids 2013, 44, 835–846.

- Marchetto, R.; Schreier, S.; Nakaie, C, R,; A novel spin-labeled amino acid derivative for use in peptide synthesis: (9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl)-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-Oxyl-4-amino-4-carboxylic acid. J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1993, 115; 11042–1143.

- Monnot C, Bihoreau C, Conchon S, Curnow KM, Corvol P, Clauser E. 1996. “Polar Residues in the Transmembrane Domains of the Type 1 Angiotensin II Receptor Are Required for Binding and Coupling”. Journal of Biological Chemistry 271(3): 1507–13.

- Morrone, J. A., Perez, A.; MacCallum, J.; Dill, K.A. . 2017. Computed binding of peptides to proteins with MELD-accelerated molecular dynamics.. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2017. 13, 870–76.

- Nakaie, C.R.; Goissis, G.; Schreier, S.; Paiva, A.C.M. pH dependence of ESR spectra of nitroxide containing ionizable groups. Braz; J. Med. Biol. Res, 1981 14, 173-180.

- Nakaie, C.R.; Schreier, S; Paiva, A.C.M. Synthesis and properties of spin-labeled angiotensin derivatives.. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1983, 742, 63-71.

- Nakaie, C.R.; Silva, E.G.; Cilli, E.M.; Marchetto, R.; Schreier, S.; Paiva, T.B.; Paiva, A.C.M. Synthesis and pharamacological properties of TOAC-labeled angiotensin and bradykinin analogs. Peptides 2002, 23, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, L., Paiva, A.C.M., Sander, C., Vriend. G. A common step for signal transduction in G protein-coupled receptors. Trend. Pharmacol. Sciences 1994, 15, 170–172.

- Oliveira, L.; Costa-Neto, C.M.; Nakaie, C.R.; Schreier, S.; Shimuta, S. I., Paiva, A.C.; The Angiotensin II AT 1 receptor structure-activity correlations in the light of rhodopsin structure. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 565–592.

- Peach, M. J.; Dostal, D. E. The angiotensin II receptor and the cctions of angiotensin II. J. Cardiov. Pharmacol. 1990, 16, S25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pignatari, G. C.; Rozenfeld, R.; Ferro, E. S.;, Oliveira, L.; Paiva, A.C.; Devi, L.A.; A role for transmembrane domains V and VI in ligand binding and maturation of the angiotensin II AT1 receptor. Biol. Chem. 2006, 387, https://www.degruyter.com/view/j/bchm.2006.387-3/bc.2006.036/bc.2006.036.xml.

- Prekash, A.; Sprenger, K.G., Pfaendtner, J.; Essential slow degrees of freedom in protein-surface simulations: a metadynamics investigation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. 2018, 498, 274–281.

- Sandberg, K., Ji, H.; Catt, K.J.; Regulation of angiotensin II receptors in rat Brain during dietary sodium changes. Hypertension 1994. 23, I137–I137.

- Schreier, S.; Barbosa, S.R.; Casallanovo, F.; Vieira, R.F.; Cilli, E.M.; Paiva, A.C.; Nakaie, C.R. Conformational basis for the biological activity of TOAC-labeled angiotensin II and bradykinin: electron paramagnetic resonance, circular dichroism, and fluorescence studies. Biopolymers 2004, 74, 389–402. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, S.; Bozelli, Jr, J. C., Marin, N., Vieira, R. F. F., Nakaie, C. R. .The spin label amino acid TOAC and its uses in studies of peptides: chemical, physicochemical, spectroscopic, and conformational aspects. Biophys. Rev. 2012, 45–66.

- Senthilkumar, B. D.; Meshach, P., Srinivasan, E.;, Rajasekaran. R. Structural stability among hybrid antimicrobial peptide Cecropin A (1–8)–Magainin 2(1–12) and its analogs: a computational approach. J. Cluster Sci. 2017, 28, 2549–63.

- Silva, R. L., Papakyriakou, A., Carmona, A. K., Spyroulias, G. A., Sturrock, E. D., Bersanetti, P.A.; Nakaie, C. R. Peptide inhibitors of angiotensin-I converting enzyme based on angiotensin (1-7) with selectivity for the C-terminal domain. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 129, 106204.

- Sharma, A K., Persichetti, J, Tale, E., Prelvukaj, G, Cropley T, Choudhury, R. A Computational examination of the binding interactions of amyloid β and human Cystatin C. J. Theor. Comput. Chem. 2018.17, 1850001.

- Tigerstedt, R.; Bergman, P. Q.; Niere Und Kreislauf . Skandinavisches Archiv Für Physiologie 1898, 8, 223–271.

- Timmermans, P.B.; Wong, P. C.; Chiu, A.T.; Herblin, W.F.; Smith, R.D.;. New perspectives in angiotensin system control. J. Human Hypert. 1993 . S19-31.

- Toniolo, C.; Crisma, M.; Formaggio, F. TOAC, a nitroxide spin-labeled, achiral C (alpha)-tetrasubstituted alpha-amino acid is an excellent tool in material science and biochemistry. Biopolymers, 1998, 47, 153-158.

- Verlander, M. 2001.Solid-phase synthesis: a practical guide, Edit. Kates, E. and Albericio, F., Marcel Dekker: New York. 2000. 826, ISBN 0-8247-0359-6.

- Yan, B.X.; Sun, Y. Q,. Glycine residues provide flexibility for enzyme active sites. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 3190–3194.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).