1. Introduction

Complications of snakebite envenomation constitute a serious public health problem causing permanent physical handicaps, irreversible kidney failure, and death, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa[

1,

2]. Snakebite victims typically present to health facilities with signs of local and/or systemic complications [

3]. The people most at risk are often poor individuals living in remote areas with limited access to healthcare.

Assessing the true extent of complications from snakebite envenomation is a challenge due to a lack of reliable statistics. However, various studies have documented the frequency of complications and their lethal consequences. Hemorrhagic complications are the most frequently reported (78.9%) [

4], and fatal outcomes occur in 7.8% of bites [

5]. In Burkina Faso, between 2010 and 2014, the annual incidence and mortality rates were 130 snakebites and 1.75 deaths per 100,000 people, respectively [

6]. Despite these statistics, few studies have investigated the factors associated with complications of snakebite envenomation in the country.

Complications and deaths often result from delayed access to care, as victims initially seek traditional treatments and only later present at health facilities with advanced complications [

3]. The use of tourniquets, a common practice, accelerates the necrosis of affected limbs. In addition, access to quality antivenom serum is frequently limited [

4,

7]. Most studies conducted in Burkina Faso have focused on the prevalence or incidence of snakebites [

6,

8,

9], while recent research on complications has been case reports from referral hospitals [

10,

11,

12]. Few studies have explored both the complications of snakebite envenomation and the associated factors.

This study aims to analyze the factors associated with complications of snakebite envenomation using data recorded in five health facilities in the Cascades region, one of the most affected areas in Burkina Faso [

6]. The results could help the National Programme for the Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases to strengthen snakebite prevention measures and improve the management of envenomation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a cross-sectional study using secondary data obtained from a review of consultation registers and patient medical records.

2.2. Study setting

Burkina Faso comprises 13 health regions, including the Cascades region, located in the southwestern part of the country. The vegetation of the region is Guinean savanna, home to various types of snakes, as vipers and cobras [

8,

13,

14]. The Cascades health region is subdivided into three health districts (Banfora, Mangodara, and Sindou) with a regional referral hospital. The study was conducted in the Banfora and Sindou health districts, involving four health facilities (Sindou Medical Center with surgical unit, Niangoloko Medical Center, Niankorodougou Medical Center, and Yendere Health and Social Promotion Center) and the Banfora Regional Hospital Center. These facilities were selected for their relevance to the study, some due to their pivotal position in the region's healthcare network, and others for regularly reporting cases of snakebite envenomation.

2.3. Study Population

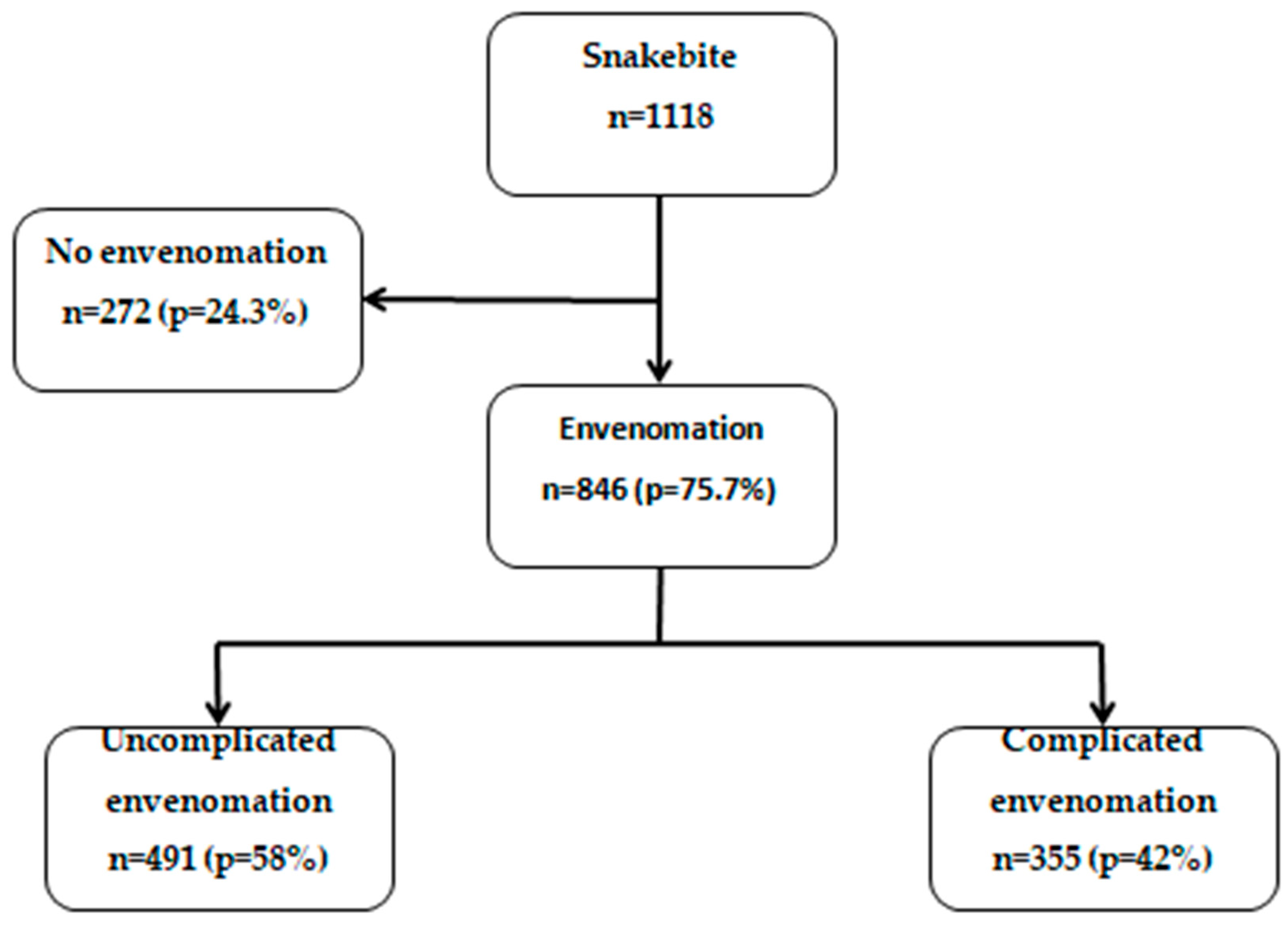

We included all individuals who consulted the selected health facilities for snakebite between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2021. The analysis focused on individuals with snakebite and envenomation admitted to these facilities during the study period (n=846,

Figure 1).

2.4. Data Collection

Variables related to the study objectives were extracted from consultation registers and patient medical records using a questionnaire developed with KoBoCollect software. Data were collected from September 29 to November 15, 2022 in the health facilities.

2.5. Measurement of variables

Envenomation by snakebite involved venom injection causing various harmful effects such as tissue damage, systemic toxicity, and symptoms depending on the specific venom of the snake species. Envenomation could lead to serious medical emergencies, requiring prompt intervention like antivenom treatment. Hemotoxicity referred to the toxic effects of snake venom targeting the blood, causing disrupted circulation, clotting problems, bleeding, vessel damage, and cell destruction. Symptoms included uncontrolled bleeding and organ damage. Neurotoxicity referred to the toxic effects of snake venom on the nervous system, leading to symptoms such as muscle weakness, paralysis, difficulty in breathing, and palpebral ptosis. Cytotoxicity was defined as causing pain, swelling, blistering, and tissue necrosis around the bite area. The venom substances directly damage and destroy cells, leading to local tissue damage at the bite site.

The dependent variable was the occurrence of snakebite complications with envenomation, defined by the presence of hemotoxic, neurotoxic or cytotoxic symptoms and signs. These corresponded to either local complications (presence of cytotoxic signs) or systemic complications (presence of hemotoxic or neurotoxic signs) requiring immediate management [

7,

15]. This was a binary variable with 1 indicating complicated envenomation and 0 indicating uncomplicated envenomation.

The independent variables included sociodemographic (age, sex, occupation, residence), clinical (presence of comorbidity, initial treatment, and course of the disease), and therapeutic (administration of antivenom serum) characteristics, which were collected from consultation registers and medical records.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data collected from consultation registers and patient medical records were analyzed using R 4.2.1 software. Characteristics of snakebite victims were presented as frequencies and percentages or as medians with interquartile ranges. Bivariate analysis was performed using the chi-squared test to explore factors associated with snakebite envenomation-related complications, and the results presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Variables with a p-value ≤ 0.20 in the bivariate analysis were included in a multivariate logistic regression model to calculate adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals. The variables included in this model were derived from a literature review and those available in the study database. Differences were considered statistically significant with p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

Figure 1 shows the flow chart of snakebite cases to envenomation and complicated envenomation in the five health facilities in the Cascades region of Burkina Faso, 2016-2021. Overall, there were 846 patients with envenomation.

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.1.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Socio-demographic characteristics of the 846 persons with envenomation are shown in

Table 1. The median age of envenomation victims was 17 years (IQR=10-32). Victims under 15 years of age (43.6%) were the most affected by snakebite envenomation. The majority of victims were male (54.6%) and lived in rural areas (88.2%). Envenomation was recorded throughout the year, with 49.2% reported in the first half and 50.8% in the second half.

3.1.2. Clinical Characteristics

Of the 846 patients, information on snake types was available for 102. Among these, 88 (86.3%) had viper bites, and 14 (13.7%) had cobra bites.

Table 2 shows the clinical characteristics of the snakebite envenomation cases. Regarding the first procedures performed at home before being taken to the hospital, the bite site was incised (23.8%), a black stone was used (13.9%), and a tourniquet was applied (7.9%) in patients with snakebite envenomation. Local signs such as edema and pain at the bite site were present in the vast majority (95.9%) of snakebite envenomation victims. The majority of signs were hemotoxicity (32.5%) with bleeding often accompanied by dyspnea (11.2%). Comorbidities (5.9%) such as severe malaria and hypertension were also present. Regarding management, 69.7% of envenomation victims received antivenom serum in the health facilities.

3.2. Frequency of Complications of Snakebite Envenomation

Overall, complications were present in 355 (42%) patients who had signs of envenomation (

Figure 1).

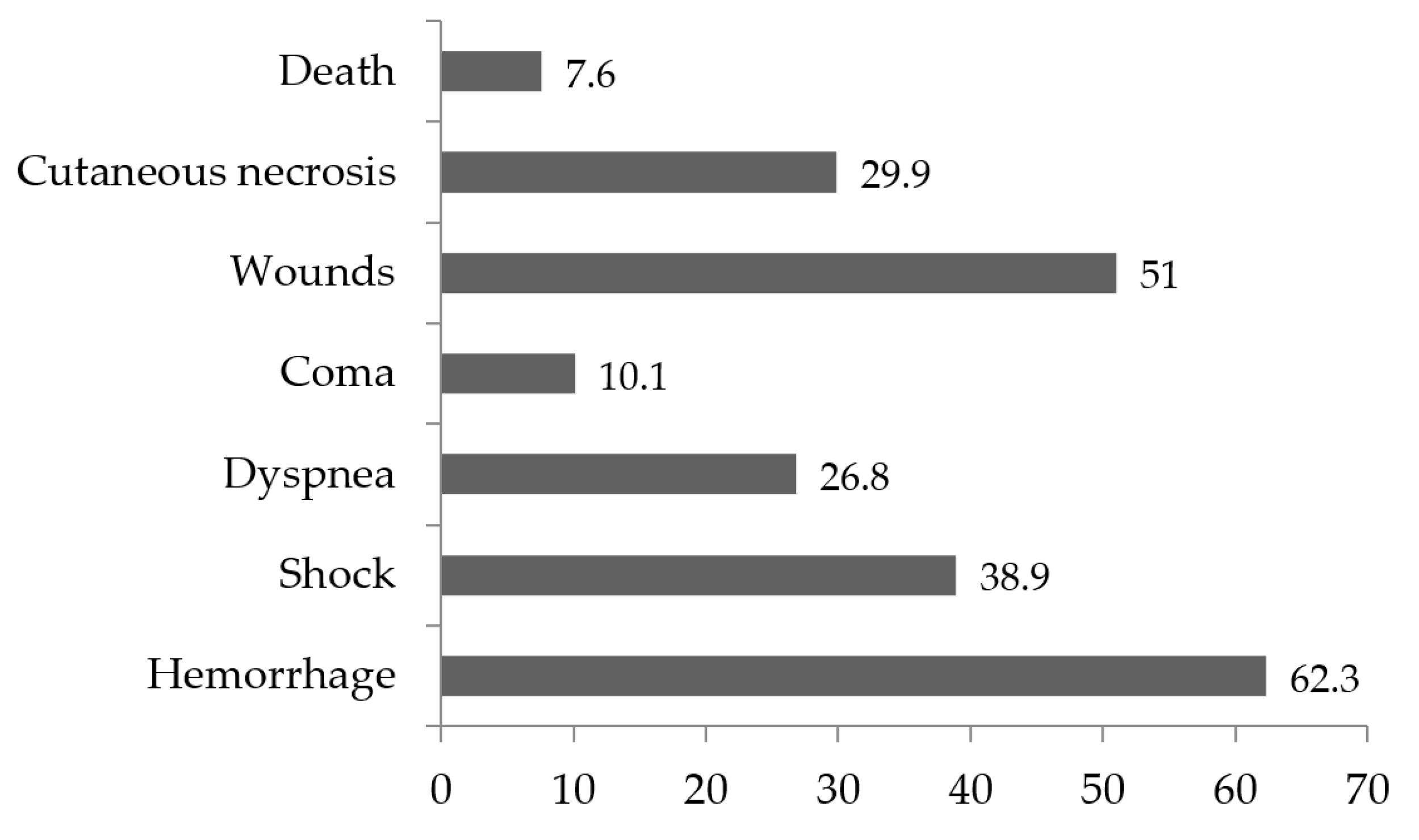

Among envenomation cases, local complications (23.2%) and systemic complications (34.3%) were observed, of which hemorrhage (62.3%), bite site wounds (51%), and shock (38.9%) were the most frequent. Death was reported with a frequency of 7.6% (Figure 3).

3.3. Factors Associated with Complications of Snakebite Envenomation

Bivariate analysis showed that age, residence, cmorbidity, incision at the anatomical bite site, tourniquet application, use of blackstone, bleeding, and the presence of abnormal vital and neurological signs were significantly associated with complications of snakebite envenomation (

Table 3).

In multivariate logistic regression, after adjusting for other variables, victims younger than 15 years (AOR: 2.04; 95% CI: 1.14-3.72), those aged 15-29 years (AOR: 1.87; 95% CI: 1.03-3.44), and those residing in rural areas (AOR: 4.80; 95% CI: 2.21-11.4) were significantly more likely to develop complications than their counterparts. The risk of developing complications after envenomation was 5 times higher when the local practice of incision at the anatomical site of the snakebite was performed (AOR: 4.31; 95% CI: 2.51-7.52) and a tourniquet was applied (AOR: 5.52; 95% CI: 1.42-30.8). Patients with abnormal vital signs (AOR: 14.3; 95% CI: 9.22-22.7) and bleeding (AOR: 14.2; 95% CI: 8.80-23.4) had 14-fold higher odds of developing complications from snakebite envenomation. Similarly, patients who did not receive antivenom serum (AOR: 2.92; 95% CI: 1.80-4.80) were three times more likely to develop complications (

Table 3).

In contrast, after adjustment, variables such as sex, time of year of envenomation, comorbidity, application of blackstone, presence of local signs, and presence of neurological signs were not independently associated with complications by snakebite envenomation.

.

.

4. Discussion

This study analyzed data on snakebite envenomation from peripheral and referral health facilities in the Cascades region of Burkina Faso to identify the frequency of resulting complications and associated risk factors. Complications were found to be frequent, with a high occurrence rate in the studied facilities.

The study revealed that over 40% of snakebite cases resulted in complications. Local complications, such as wounds and skin necrosis, were observed in 23% of cases, while systemic complications, including hemorrhages, shock, and coma, were observed in 34%. These complications often required immediate medical intervention. Mortality was observed in less than 10% of patients with complications. Incision of the anatomical bite site and application of tourniquets, which were common local practices, may have accelerated the occurrence of some of these complications.

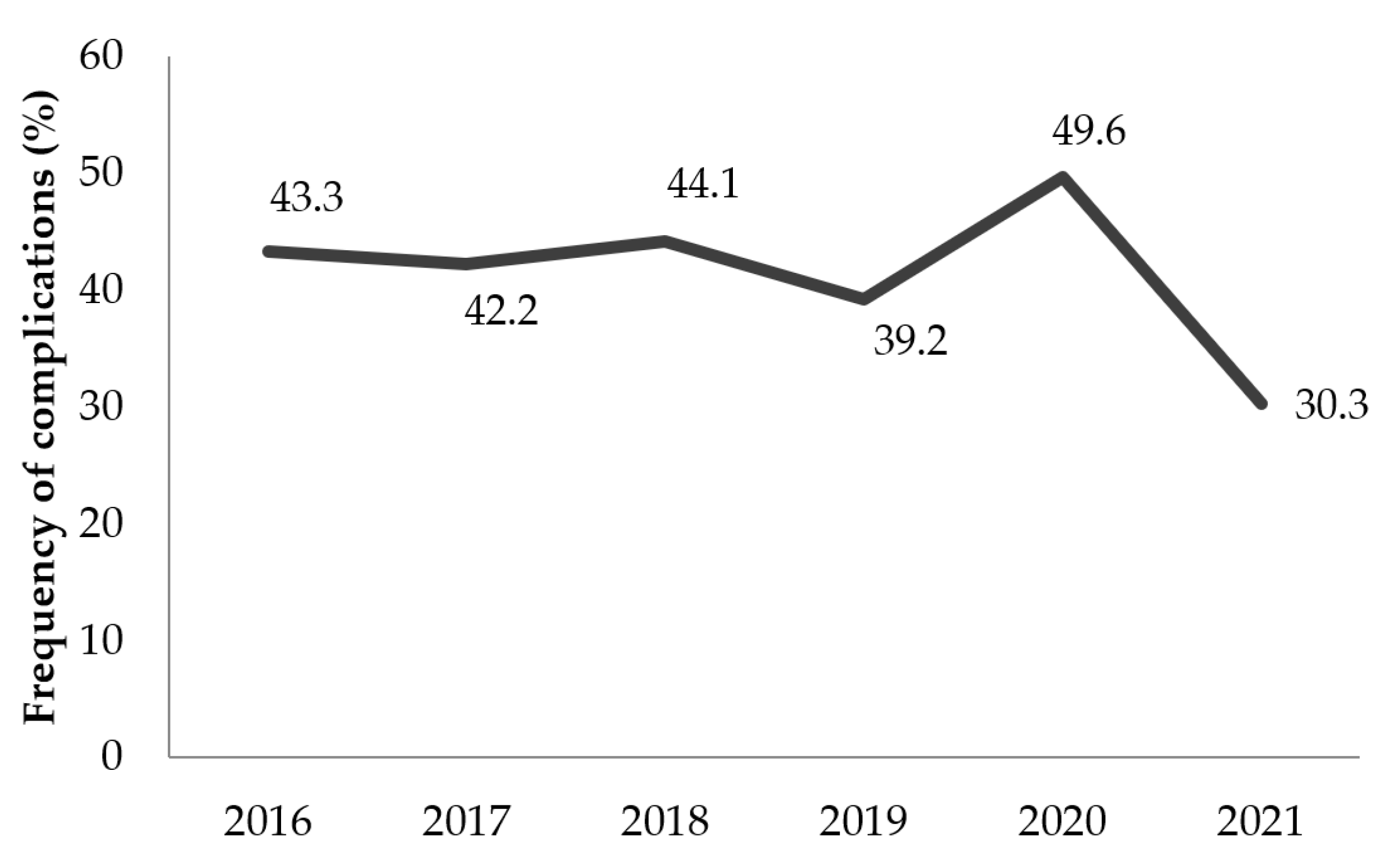

The frequency of complications in the region showed a steady trend over the years. The implementation of the World Health Organization (WHO) strategy for snakebite prevention and strengthening the management of envenomation with a subsidy for the procurement of antivenom serums would be difficult to apply in the region. Antivenoms were not accessible or affordable for all snakebite victims. These victims thus used traditional treatments or self-medication and only resorted to healthcare facilities when complications arose [

16]. Improved awareness among the population, particularly in rural areas, is essential. This awareness should cover the ecology of dangerous snakes, proper first aid for snakebites, the use of repellents, wearing protective footwear, and the availability of affordable antivenom in health facilities. These measures could significantly reduce complications resulting from snakebites in the region [

7].

The study found that rural populations were nearly five times more likely to develop complications compared to urban populations. This situation could be explained by the frequent recourse of rural victims to traditional medicine due to cultural proximity to traditional practitioners coupled with geographical and financial inaccessibility to modern healthcare [

1,

7]. Convinced of the ineffectiveness of biomedical treatments, some victims preferred traditional care with local incision and tourniquet application practices, both of which favored the onset of complications. It was only at the onset of these complications that victims presented themselves to health facilities for better care [

17]. Although snakebites occurred at all ages, the pediatric population under 15 years of age was more susceptible and accounted for a significant proportion of envenomation cases at 44%. Children under 15 years of age and adults aged 15 to 30 were approximately twice as likely to develop envenomation-related complications as victims aged 30 and older. The severity of envenomation depends on the volume of venom injected and the degree to which it is absorbed. This may explain the vulnerability of children to complications after snakebite envenomation because they have a smaller body surface area and therefore a higher concentration of venom [

18,

19].

Bleeding from mucous membranes, recent wounds, or scars was common in the study sample. Observed cases included epistaxis, gingivorrhagia, hematemesis, hemoptysis, and a few melena and hematuria. The presence of bleeding increased the risk of complications by a factor of 14. Snake venoms, mainly those of the

Viperidae family, contain enzymes that alter cell membranes, vascular walls, and the blood coagulation cascade [

20,

21]. Bleeding related to blood coagulation disorders may have led to hypovolemic shock states observed in this study. The increase in vascular permeability due to snake venom would have caused other complications that could explain the risk associated with the development of abnormal vital signs. Hemoperitoneum, subdural hematoma, acute renal failure, and pulmonary edema have been reported in previous studies [

17,

21]. Cardiotoxic effects of the venom, which could not be analyzed in this study, may have contributed to complications or death [

22]. The failure to administer antivenom serum significantly increased the risk of complications. Although antivenoms are available in some health facilities, their high cost makes them inaccessible to most victims. Early administration of antivenom is crucial for effective treatment [

23]. Therefore, making antivenoms affordable and available in primary health centers, especially in rural areas, is recommended.

Our study has limitations inherent in the retrospective nature of the data collected. In addition, the study relied on routine data from consultations and medical records. These records had missing data on some characteristics of snakebite victims. A further limitation was the absence of some independent variables from the data sources, which might have led to a better understanding of other factors related to envenomation complications. Thus, it is possible that not all confounders were examined or accounted for in the multivariate regression model. For example, we were not able to include the type of snakebite and the site of the bite as variables.

5. Conclusions

This study provided baseline information on the factors associated with snakebite envenomation complications in the Cascades region of Burkina Faso. The significant factors identified were rural residence, young age, incision at the bite site, and tourniquet application. Additionally, bleeding and the presence of abnormal vital signs were strongly associated with complications. The administration of antivenom serum reduced the risk of these complications. The availability of antivenom serum in rural areas and educating the population on seeking prompt medical care could reduce the occurrence of complications related to snakebite envenomation. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm the results of this study and to better understand other potential factors influencing envenomation complications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.K., S.S., D.Z.; methodology, R.K., S.S., D.Z.; validation, T.M., A.D., and S.K.; formal analysis, R.K.; investigation, R.K.; resources, S.K., and R.K.; data curation, R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.K.; writing—review and editing, S.S., D.Z., T.M., A.D., and S.K. ; visualization, R.K.; supervision, S.S., D.Z., T.M., A.D., and S.K.; project administration, T.M.; funding acquisition, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This SORT IT course on NTDs in Burkina Faso was funded by TDR, the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the World Health Organization (WHO) and implementing partners. TDR is able to conduct its work thanks to the commitment and support from a variety of funders. A full list of TDR donors is available at https://tdr.who.int/about-us/our-donors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Burkina Faso Health Research Ethics Committee (CERS) (deliberation no 2022-08-195).

Informed Consent Statement

Because of the retrospective nature of the data, informed consent was not required for study participation in accordance with national legislation and institutional requirements.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article can be made available by the authors without reservation.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT) a global partnership coordinated by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) at the World Health Organization (WHO). The specific SORT IT on Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) that led to these publications included a partnership of TDR with the National Programme for the Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases of the Ministry of Health and Public Hygiene of Burkina Faso, the African Institute of Public Health (AIPH), the Africa Center of Excellence for Prevention and Control of Communicable Diseases (CEA-PCMT) of the University Gamal Abdel Nasser of Conakry, the Cascades Regional Department of Health and Public Hygiene, the General Direction of the Banfora Regional Hospital, the Technical Direction of the National Malaria Research and Training Centre (CNRFP), and the WHO country in Burkina Faso.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Chippaux, J.-P.; Massougbodji, A.; Habib, A.G. The WHO strategy for prevention and control of snakebite envenoming: a sub-Saharan Africa plan. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 25, e20190083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chippaux, J.-P.; Akaffou, M.H.; Allali, B.K.; Dosso, M.; Massougbodji, A.; Barraviera, B. The 6(th) international conference on envenomation by Snakebites and Scorpion Stings in Africa: a crucial step for the management of envenomation. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcoba, G.; Chabloz, M.; Eyong, J.; Wanda, F.; Ochoa, C.; Comte, E.; et al. Snakebite epidemiology and health-seeking behavior in Akonolinga health district, Cameroon: Cross-sectional study. Hodgson W, éditeur. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touré M, Coulibaly, Koné J, Diarra M, Coulibaly B, Beye S, et al. Complications aigues de l’envenimation par morsures de serpent au service de réanimation du CHU mère enfant ‘‘LE Luxembourg’’ de Bamako. Mali Médical. 2019;Tome XXXIV:48-52.

- Chippaux, J.-P. Estimate of the burden of snakebites in sub-Saharan Africa: A meta-analytic approach. Toxicon 2011, 57, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gampini, S.; Nassouri, S.; Chippaux, J.-P.; Semde, R. Retrospective study on the incidence of envenomation and accessibility to antivenom in Burkina Faso. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorge F, Chippaux JP. Prise en charge des morsures de serpent en Afrique. La Lettre de l’Infectiologue. 2016;Tome XXXI:152-7.

- Bamogo, R.; Thiam, M.; Nikièma, A.S.; Somé, F.A.; Mané, Y.; Sawadogo, S.P.; Sow, B.; Diabaté, A.; Diatta, Y.; Dabiré, R.K. Snakebite frequencies and envenomation case management in primary health centers of the Bobo-Dioulasso health district (Burkina Faso) from 2014 to 2018. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 115, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Koudou, G.B.; Bagot, M.; Drabo, F.; Bougma, W.R.; Pulford, C.; et al. Health and economic burden estimates of snakebite management upon health facilities in three regions of southern Burkina Faso. Monteiro WM, éditeur. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouedraogo, P.V.; Traore, C.; Savadogo, A.A.; Bagbila, W.P.A.H.; Galboni, A.; Ouedraogo, A.; Sere, I.S.; Millogo, A. [Cerebral-meningeal hemorrhage secondary to snakebite envenomation: about two cases at the Sourô Sanou Teaching Hospital in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso]. . 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabilgou, A.A.; Sondo, A.; Dravé, A.; Diallo, I.; Kyelem, J.M.A.; Napon, C.; Kaboré, J. Hemorrhagic stroke following snake bite in Burkina Faso (West Africa). A case series. Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines 2021, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyelem, C.; Yaméogo, T.; Ouédraogo, S.; Zoungrana, J.; Poda, G.; Rouamba, M.; Ouangré, A.; Kissou, S.; Rouamba, A. Snakebite in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso: illustration of realities and challenges for care based on a clinical case. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 18, 483–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chippaux J-P. Les serpents d’Afrique occidentale et centrale. Éditions de l’IRD (EX-ORSTOM). 2001;310.

- Chirio, L. Inventaire des reptiles de la région de la Réserve de Biosphère Transfrontalière du W (Niger/Bénin/Burkina Faso : Afrique de l’Ouest). Bull Soc Herp Fr. 2009;132:13-41.

- Chippaux, J.-P. Management of Snakebites in Sub-Saharan Africa. Med. Et Sante Trop. 2015, 25, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.J.; Faiz, M.A.; Abela-Ridder, B.; Ainsworth, S.; Bulfone, T.C.; Nickerson, A.D.; Habib, A.G.; Junghanss, T.; Fan, H.W.; Turner, M.; et al. Strategy for a globally coordinated response to a priority neglected tropical disease: Snakebite envenoming. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulibaly M, Mangane MI, Ouedrago Y, Koita SA, Madane DT, Hamidou AA, et al. Overview of poisoning by snake bite in 2019 at UHC Gabriel Touré of Bamako: Clinical features, prognosis and evaluation of the availability of antivenom serum. 2021;7. [CrossRef]

- Gerardo, C.J.; Vissoci, J.R.N.; Evans, C.S.; Simel, D.L.; Lavonas, E.J. Does This Patient Have a Severe Snake Envenomation?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essafti, M.; Fajri, M.; Rahmani, C.; Abdelaziz, S.; Mouaffak, Y.; Younous, S. Snakebite envenomation in children: An ongoing burden in Morocco. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 77, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.S.; Narayanan, S.; Udayabhaskaran, V.; Thulaseedharan, N. Clinical and epidemiologic profile and predictors of outcome of poisonous snake bites – an analysis of 1,500 cases from a tertiary care center in Malabar, North Kerala, India. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2018, ume 11, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhaskar, D.; Agarwal, A.; Bhalla, G. A study of clinical profile of snake bite at a tertiary care centre. Toxicol. Int. 2014, 21, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harikrishnan, M.P.; Kumar, C.R.A.; Anand, M.K.; Earali, J. Effects of hemotoxic snake bite envenomation on haematological parameters variability in predicting complications. Int. J. Med. Med Res. 2021, 6, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Masroori, S.; Al Balushi, F.; Al Abri, S. Evaluation of Risk Factors of Snake Envenomation and Associated Complications Presenting to Two Emergency Departments in Oman. Oman Med J. 2022, 37, e349–e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).