Submitted:

27 May 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

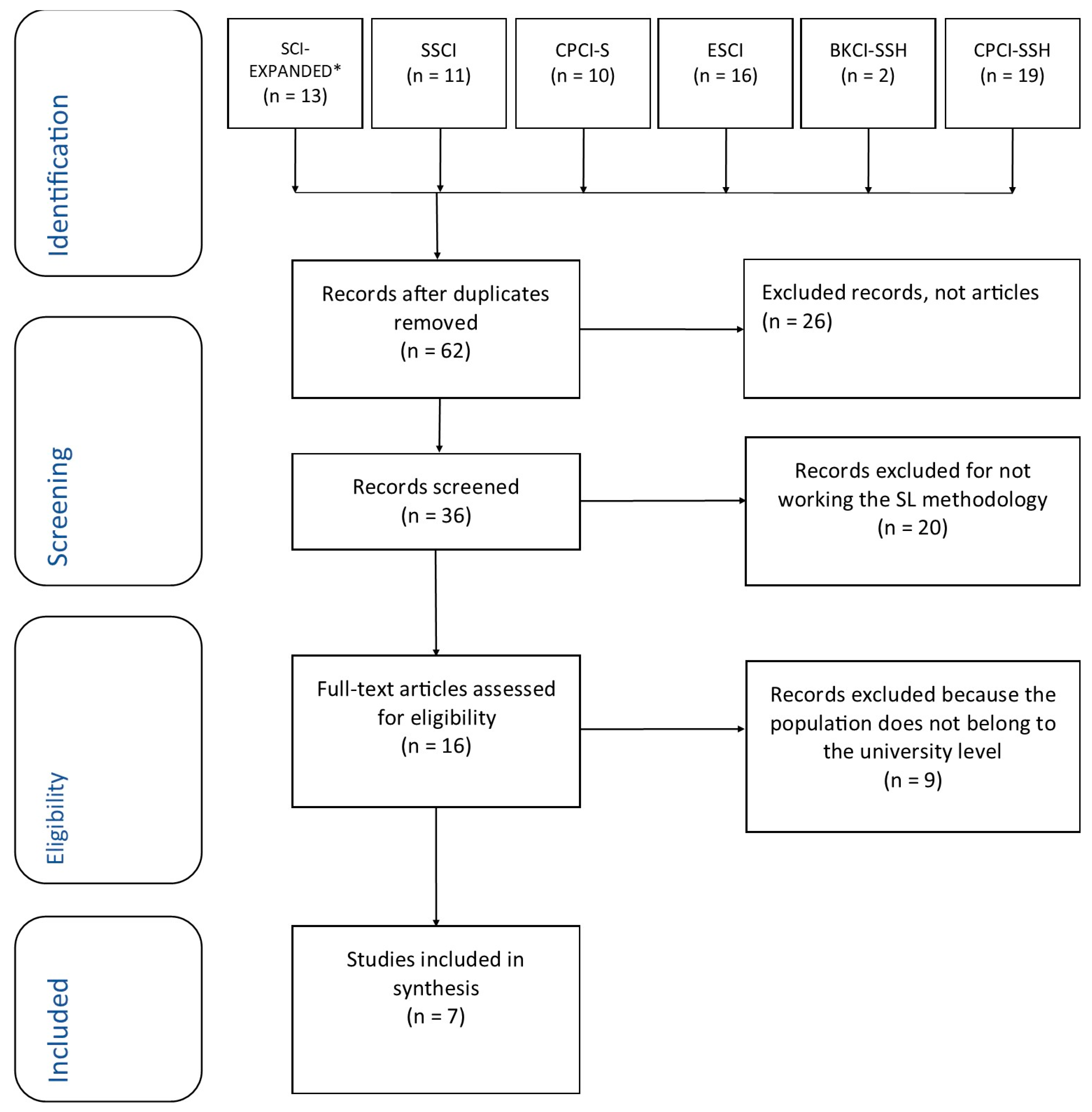

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

3. Results

3.1. Service-Learning Outcomes (SLO)

3.2. Results of Pedagogical Practices

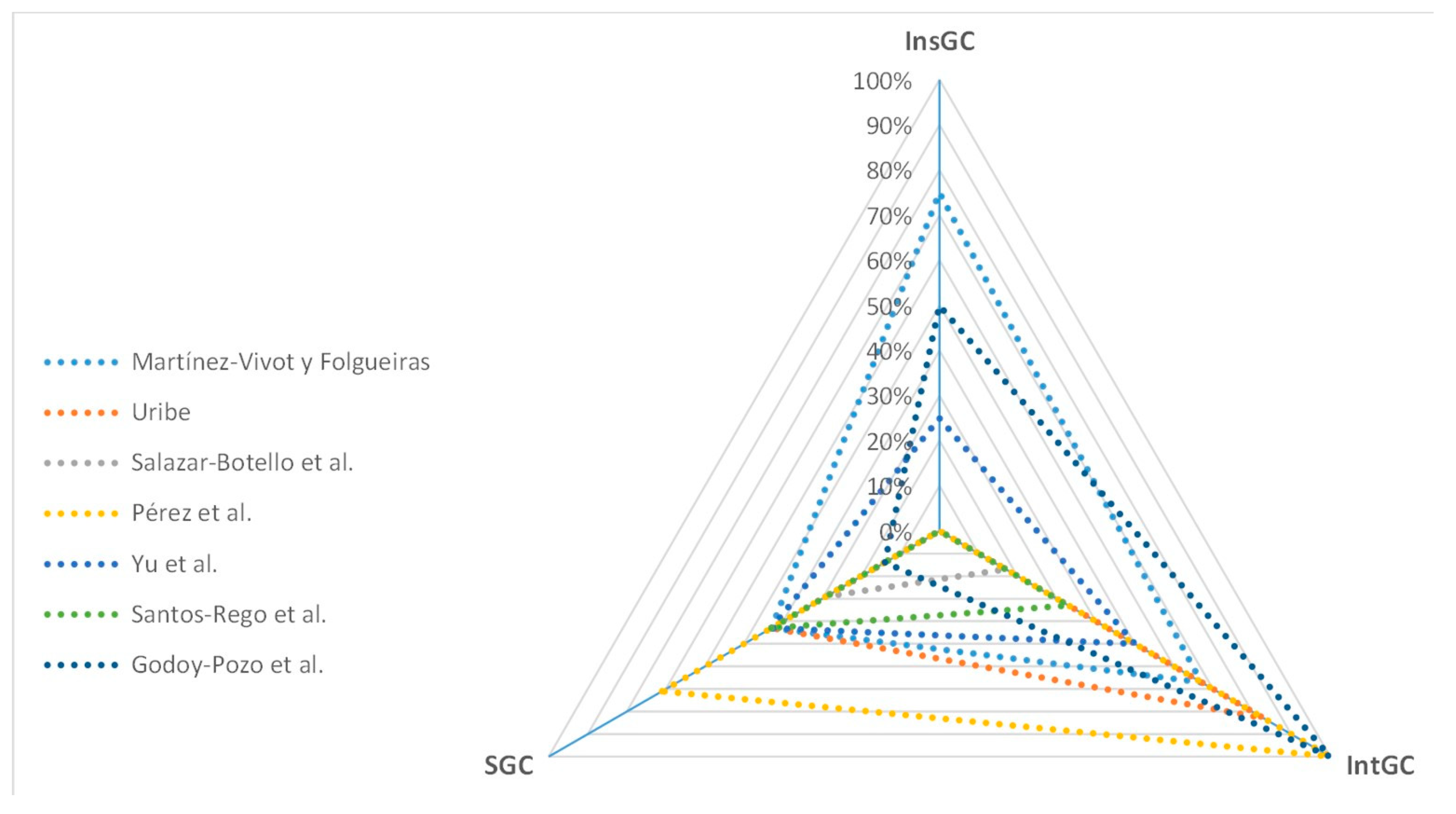

3.3. Results of Generic Competencies

3.3.1. Results of Instrumental Generic Competencies

3.3.2. Results Interpersonal Generic Competencies

3.3.3. Results Systemic Competencies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beneitone, P.; Esquetini, C.; González, J.; Marty, M.; Siufi, G.; Wagenaar, R. Eds. Reflexiones y perspectivas de la educación superior en América Latina: informe final Proyecto Tuning América Latina: 2004-2007. Universidad de Deusto: Bilbao, España, 2007. 430 págs. Available online: https://tuningacademy.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/TuningLAIII_Final-Report_SP.pdf.

- Corominas, E. Competencias genéricas en la formación universitaria. Rev. Educ. 2001, 325, 299–321. Available online: https://dialnet. unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=19417.

- Corominas, E.; Tesouro, M.; Capell, D.; Teixidó, J.; Pelach, J.; Cortada, R. Percepciones del profesorado ante la incorporación de las competencias genéricas en la formación universitaria. In Rev. Educ.; 2006; 341, pp. 301–336. Available online: http://www.educacionfpydeportes.gob.es/dam/jcr:2c0d3f04-bbb3-4b8c-a7f4-0417867e83b6/re34114-pdf.pdf.

- González, J.; Wagenaar, R. Tuning Educational Structures in Europe II. La contribución de las universidades al proceso de Bolonia. Universidad de Deusto: Bilbao, España, 2006. 424 págs. http://www.deustopublicaciones.es/deusto/pdfs/tuning/tuning04.pdf.

- Tobón, S. Formación integral y competencias. Pensamiento complejo, currículo, didáctica y evaluación, 4° ed.; Ecoe: Bogotá, Colombia, 2013; 328 págs, Available online: https://cife.edu.mx/recursos/formacion-integral-y-competencias-pensamiento-complejo-curriculo-didactica-y-evaluacion/.

- Villardon, L. Evaluación del aprendizaje para promover el desarrollo de competencias. Educ. Siglo XXI 2006, 57-76. http://revistas.um.es/educatio/article/download/153/136.

- Amor, MI; Serrano, R. Análisis y Evaluación de las Competencias Genéricas en la Formación Inicial del Profesorado. Estud. Pedagógicos 2018, XLIV, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel, V.; Bruna, D. Reflexiones en torno a las competencias genéricas en educación superior: Un desafío pendiente. Psicoperspectivas 2014, 13, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yániz, C. Planificar la enseñanza universitaria para el desarrollo de competencias. Educ. Siglo XXI 2006, 24, 17–34. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/educatio/article/view/151.

- Lemaitre, MJ; Zenteno, ME Eds. Aseguramiento de la calidad en Iberoamérica. Educación Superior en Iberoamérica Informe 2012; RIL: Santiago, Chile, 2012. 318 págs. https://cinda.cl/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/aseguramiento-de-la-calidad-en-iberoamerica-educacion-superior-informe-2012.pdf.

- Cancino, V.; Iturra, C. Gestión curricular en un enfoque por competencias: aspectos claves y avances en el sistema universitario chileno. En La formación por competencias en la educación superior: alcances y limitaciones desde referentes de España, México y Chile; Leyva, O., Ganga, F., Tejada, J., Hernández, A. Eds.; Tirant Humanidades: México, 2018; 307-326. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306999046_Gestion_de_un_curriculum_por_competencias_aspectos_claves_y_tensiones_en_el_sistema_universitario_chileno.

- Martínez-Usarralde, M.J.; Gil-Salom, D.; Macías-Mendoza, D. Revisión sistemática de responsabilidad social universitaria y aprendizaje servicio. Análisis para su institucionalización. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. 2019, 24, 149–172. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/140/14060241007/.

- Ribeiro, LM; Miranda, F.; Themudo, C.; Gonçalves, H.; Bringle, RG; Rosario, P.; et al. Educating for the sustainable development goals through service-learning: University students’ perspectives about the competences developed. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efimova, G.; Sorokin, A.; Gribovskiy, M. Ideal teacher of higher school: Personal qualities and socio-professional competencies. Educ. Sci. J. 2021, 23, 202–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuwita, P. Teacher’s Pedagogic Competence In Civics Learning To Fostering Student Character In Elementary Schools. In Atlantis Press 2019. In International Conference Primary Education Research Pivotal Literature and Research UNNES 2018 pp. 71-76.

- Frye, S.; McCarron, G.P. Leveraging High-Impact, Collaborative Learning in an Undergraduate Nonprofit Studies Course Toward Bolstering Career Readiness. J. Nonprofit Educ. Leadersh 2021, 11, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalta, M.A.; Assael, C.; Baeza, A. Conversación y mediación del aprendizaje en aulas de diversos contextos socioculturales. Perfiles Educ. 2018, XL, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szelei, N.; Tinoca, L.; Pino, A.S. Professional development for cultural diversity: the challenges of teacher learning in context. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2020, 46, 780–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forghani-Arani, N.; Cerna, L.; Bannon, M. The lives of teachers in diverse classrooms; OECD: París, Francia, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, D. Aprendizaje-Servicio: una práctica educativa innovadora que promueve el desarrollo de competencias del estudiantado universitario. Rev. Electrónica Actual Investig. en Educ. 2018, 18, 494–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.A.; Sotelino, A.; Lorenzo, M. Aprendizaje-servicio y misión cívica de la universidad. Una propuesta de desarrollo; Octaedro: Barcelona, España, 2015; 134 págs. [Google Scholar]

- Aramburuzabala, P.; Cerrillo, R.; Tello, I. Apendizaje-Servicio: una propuesta metodológica para la introducción de la sostenibilidad curricular en la Universidad. Profesorado. Rev. Curric. Form. Profr. 2015, 19, 78–95. Available online: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/profesorado/article/view/41024.

- Sigmon, R. Service-Learning: Three principles. Synergist 1979, 8, 9–11. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.33120643.

- Furco, A.; Billig, S. Service-learning: The Essence of the Pedagogy; Information Age Publishing: EEUU, 2002; 301 págs. [Google Scholar]

- Eyler, J. The power of experiential education. In Lib. Educ.; 2009; 95, pp. 24–31. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ871318.pdf.

- Tapia, M.N. La propuesta pedagógica del “aprendizaje-servicio”: Una perspectiva Latinoamericana. Rev. Científica TzhoeCoen 2010, 3, 23–44. Available online: https://www.clayss.org.ar/04_publicaciones/TZHOECOEN-5.pdf.

- Battle, R. ¿De qué hablamos cuando hablamos de aprendizaje-servicio? Crítica 2011, 61, 49–54. Available online: http://www.revista-critica.com/administrator/components/com_avzrevistas/pdfs/b8a385038a9016caf4fb15d0f6c378b8-972-Por-una-educaci--n-transformadora---mar.abr%202011.pdf.

- Puig, J.; Guijón, M.; Martín, X.; Rubio, L. Aprendizaje-servicio y Educación para la Ciudadanía. Rev. Educ. 2011, 45–67. Available online: http://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/dctm/revista-de-educacion/articulosre2011/re201103.pdf?documentId=0901e72b81202f3d.

- Folgueiras, P.; Luna, E. El aprendizaje y servicio, una metodología participativa que fomenta los aprendizajes. Quad. Digit. Rev. Nuevas Tecnol. Soc 2011, 53–60. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8108430.

- Martínez-Vivot, M.; Folgueiras, P. Evaluación participativa, Aprendizaje-Servicio y universidad. Profesorado. Rev. Currículum Form. Profr. 2015, 19, 128–143. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/567/56738729008.pdf.

- Santos, M.A.; Mella, I.; Naval, C.; Vázquez, V. The Evaluation of Social and Professional Life Competences of University Students Through Service-Learning. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K. A practical guide for designing a course with a ServiceLearning component in higher education. J. Fac. Dev. 2012, 26, 29–36. Available online: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/magna/jfd/2012/00000026/00000001/art00004.

- Puig, J. En busca de otra forma de vida. Rev. Digit. Asoc. Convives 2014, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Opazo, H.; Aramburuzabala, P.; McIlrath, L. Aprendizaje-servicio en la educación superior: once perspectivas de un movimiento global. Bordón 2019, 71, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburuzabala, P.; Santos-Pastor, M.L.; Chiva-Bartoll, Ó.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J. Perspectivas y retos de la intervención e investigación en aprendizaje-servicio universitario en actividades físico-deportivas para la inclusión social. Publicaciones 2019, 49, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, J.; Palos, J. Rasgos Pedagógicos del aprendizaje-servicio. Cuad. Pedagog. 2006, 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios, S.; Rubio, M.; Gutiérrez, M.; Sepúlveda, C. Aprendizaje-servicio como metodología para el desarrollo del pensamiento crítico en educación superior. Educ. Médica Super. 2012, 26, 594–603. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/en/lil-657874?lang=en.

- Redondo-Corcobado, P.; Fuentes, J.L. La investigación sobre el Aprendizaje-Servicio en la producción científica española: una revisión sistemática. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2020, 31, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, MN La solidaridad como pedagogía: el aprendizaje-servicio en la escuela; Ciudad Nueva: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2000. 319 págs. https://sitios.ucsc.cl/cidd/wp-content/uploads/sites/37/2020/10/2000_La_solidaridad_pedagogia. Available online: https://sitios.ucsc.cl/cidd/wp-content/uploads/sites/37/2020/10/2000_La_solidaridad_pedagogia.pdf.

- Pérez, L.M.; Ochoa, A. El aprendizaje-servicio (ApS) como estrategia para educar en ciudadanía. Alteridad Rev. Educ. 2017, 12, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Prado, J.S.; Lozano-Díaz, A. Origen, historia e institucionalización del Aprendizaje Servicio. En Aprendizaje Servicio en la Universidad: un dispositivo orientado a la mejora de los procesos formativos y la realidad social; Mayor, D., Granero, A., Eds.; Octaedro: Barcelona, España, 2021; pp. 39–53. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351073237_Origen_historia_e_institucionalizacion_del_Aprendizaje-Servicio.

- Tapia, M.N. Aprendizaje-Servicio, un movimiento pedagógico mundiales. In En Aprendizaje-servicio (ApS): claves para su desarrollo en la universidad; Rubio, L., Escofet, A., Eds.; Octaedro: Barcelona, España, 2017; pp. 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Urrutia, G.; Bonfill, X. PRISMA declaration: A proposal to improve the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Med. Clínica 2010, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagendrababu, V.; Dilokthornsakul, P.; Jinatongthai, P.; Veettil, S.; Pulikkotil, S.; Duncan, H.; et al. Glossary for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manterola, C.; Vial, M.; Pineda, V.; Sanhueza, A. Systematic Review of Literature with Different Types of Designs. Int. J. Morphol. 2009; 27, 1179–1186. Available online: https://scielo.conicyt.cl/pdf/ijmorphol/v27n4/art35.pdf.

- Liberati, A.; Altman., D.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.; Ioannidis, J.; et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D. PRISMA Group. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for sstematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med, 2009; 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt., P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Methley, A.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabou, S.; Iglewski, M. Combination of conditional random field with a rule based method in the extraction of PICO elements. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Szolovits, B. Advancing PICO element detection in biomedical text via deep neural networks. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 3856–3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, C.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, P. Percepción de los estudiantes de educación inicial frente al desarrollo de experiencias formativas en modalidad A+S. Rev. Electrónica Investig. Educ. 2018, 20, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Botello, C.M.; Muñoz, Y.A.; Lagos, M.T.; Arriagada, R.; Vallejos, R.L.; Monje-Sanhueza, R.J. Institucionalización del aprendizaje servicio en la Facultad de Ciencias Empresariales de la Universidad del Bío-Bío: vinculando la educación superior y la comunidad local. Hallazgos 2021, 18, 287–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, N.R.; Cleveland, M.R.; Lleras, S.A.; Cortés, N.; Cortés, E. Educación ambiental mediante la metodología aprendizaje–servicio: percepción de adquisición de competencias e impacto en la comunidad. Rev. Univ. Soc. 2019, 11, 154–162. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2218-36202019000400154&lng=es&tlng=es.

- Yu, L.; Shek, D.T.; Xing, K.Y. Impact of a Service-Learning Programme in Mainland China: Views of Different Stakeholders. In Service-learning for youth leadership: the case of Hong Kong; Shek, D.T., Ngai, G., Chan, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapur, 2019; pp. 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Pozo, J.; Águila, D.; Rivas, T.; Sánchez, J.; Illesca-Pretty, M.; Flores, E.; et al. Service-learning: experience of teacher-tutors in the nursing career. Medwave 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor, G.; Segalàs, J.; Barrón, Á.; Fernández-Morilla, M.; Fuertes, MT; Ruiz-Morales, J.; et al. Didactic Strategies to Promote Competencies in Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Penguin Books: Londres, Inglaterra, 2017; 160 págs. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, PM; Ares-Pernas, A.; Dapena, A. Service-Learning Projects in University Degrees Based on Sustainable Development Goals: Proposals and Results. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, D. Dimensiones pedagógicas que configuran las prácticas de aprendizaje-servicio. Páginas Educ. 2019, 12, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburuzabala, P.; Cerrillo, R. Service-Learning as an Approach to Educating for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor-Paredes, D.; Guillén-Gámez, F. Aprendizaje-Servicio y responsabilidad social del estudiantado universitario: un estudio con métodos univariantes y correlacionales. Aula Abierta 2021, 50, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.S. The practice of professional skills and civic engagement through service learning: A Taiwanese perspective. High Educ. Ski Work-Based Learn 2018, 8, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabalza, M.Á. Competencias docentes del profesorado universitario. Calidad y desarrollo profesional, 2.a ed.; Narcea: Madrid, España, 2010; 232 págs. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D. Teaching Professional Use of Social Media Through a Service-Learning Business Communication Project. Bus. Prof. Commun. Q. 2022, 85, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Maldonado, P.; Armengol, C.; Muñoz, J.L. Interacciones en el aula desde prácticas pedagógicas efectivas. Rev. Estud. Exp. en Educ. 2019, 18, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguita, R.; Pradena, Y.; Ruiz, I. Derechos Humanos, infancia y entidades del tercer sector: una experiencia de Aprendizaje-Servicio en la Formación Inicial de Educación Primaria. En Aprendizaje-Servicio en la universidad: Un dispositivo orientado a la mejora de los procesos formativos y la realidad social; Mayor, D., Granero, A., Eds.; Octaedro: Barcelona, España, 2021; pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Jouannet, C.; Salas, M.H.; Contreras, M.A. Modelo de implementación de Aprendizaje-Servicio (A+S) en la UC. Una experiencia que impacta positivamente en la formación profesional integral. Calid. en Educ. 2013, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arquero-Avilés., R.; Cobo-Serrano, S.; Marco-Cuenca, G.; Siso-Calvo., B. Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible y Aprendizaje Servicio en la docencia universitaria: un estudio de caso en el área de Biblioteconomía y Documentación. Ibersid Rev. Sist. Inf. Doc. 2020, 14, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, A.; Pérez, L.M.; Salinas, J.J. El aprendizaje-servicio (APS) como práctica expansiva y transformadora. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 2018, 76, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Izquierdo, R. Aprendizaje Servicio y compromiso académico en educación Superior. Rev. Psicodidáct. 2020, 25, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgueiras, P.; Luna, E.; Puig, G. Aprendizaje y servicio: estudio del grado de satisfacción de estudiantes universitarios. Rev. Educ. 2013, 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor-Paredes, D.; Solís-Galán, M.G.; Ochoa-Cervantes, A. Percepción del profesorado universitario implicado en prácticas de Aprendizaje-Servicio. Un estudio cualitativo. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2023, 34, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PICOS | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | Undergraduate students (1st to 6th year) and graduate students who have worked with Service-Learning (SL) during their undergraduate training. Teachers working with SL methodology. |

| Interventions | Application of questionnaires, observation guidelines, surveys; application of semi-structured and in-depth interviews. |

| Comparators | What was used were Service-Learning (SL), Pedagogical Practices, and Generic Competencies. |

| Outcomes | Importance and benefits of SL. Generic competencies developed by SL. |

| Study design | Qualitative, descriptive, exploratory studies were included; quantitative, descriptive, longitudinal, quasi-experimental; mixed, considering the MMAT quality criteria. |

| Authors | Affiliations | Journal | Pub. Year | Sample | WoS Index | Times Cited, WoS Core | Category of Study Designs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martinez-Vivot, et al. [30] |

Univ. de Buenos Aires; Univ. de Barcelona | Profr. - Rev. Curric. Form. Profr. | 2015 | 30 students between 22 and 40 years old | ESCI | 4 | Mixed |

| Uribe [53] |

Univ. Autónoma de Chile | Rev. Electronica Investig. Educ. | 2018 | 26 students, 3 teachers, 8 municipal rural schools in an indigenous context | ESCI | 0 | Qualitative |

| Salazar-Botello et al. [54] |

Univ. del Bio-Bio | Hallazgos-Rev. Investigaciones | 2021 | 608 students, 19 teachers, 130 community partners | ESCI | 0 | Quantitative, descriptive, longitudinal |

| Perez et al. [55] | Univ. Católica del Norte; Pontificia Univ. Javeriana | Rev. Univ. y Soc. | 2019 | 56 students, 1 teacher, 6 community partners | ESCI | 1 | Qualitative |

| Yu et al. [56] | Hong Kong Polytechnic University | Service-learning for Youth Leadership: the case of Hong Kong | 2019 | 79 students, 18 teachers, 355 children | BKCI-SSH | 0 | Quantitative |

| Santos et al. [31] | Univ. de Santiago de Compostela; University of Navarra; University of Valencia | Front. in Educ. | 2021 | 1153 students, (789 experimental group; 364 control group) | ESCI | 5 | Quantitative, quasi-experimental |

| Godoy-Pozo et al. [57] | Univ. Austral de Chile; Univ. de La Frontera; Univ. Mayor | Medwave | 2021 | 5 teachers between 35 and 50 years old | ESCI | 1 | Qualitative, descriptive, exploratory, case study |

| Authors | Study Designs |

S1 | S2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [30] | Mixed | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100% | ||||||||||

| [53] | Qualitative | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100% | ||||||||||

| [54] | Quantitative | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 86% | ||||||||||

| [55] | Qualitative | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100% | ||||||||||

| [56] | Quantitative | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 86% | ||||||||||

| [31] | Quantitative | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100% | ||||||||||

| [57] | Qualitative | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| References | Ability to organize and plan | Basic knowledge of the profession | Oral and written communication | Problem-solving | Total InsGC |

% InsGC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [30] | x | x | x | 3 | 75% | |

| [53] | 0 | 0% | ||||

| [54] | 0 | 0% | ||||

| [55] | 0 | 0% | ||||

| [56] | x | 1 | 25% | |||

| [31] | 0 | 0% | ||||

| [57] | x | x | 2 | 50% | ||

| Total | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| References | Teamwork | Valuation and respect for diversity and multiculturalism |

Ethical commitment | Critical and self-critical ability | Social responsibility |

Interpersonal skills | Total IntGC |

% IntGC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [30] | x | x | x | x | 4 | 67% | ||

| [53] | x | x | x | x | x | 5 | 83% | |

| [54] | x | 1 | 17% | |||||

| [55] | x | x | x | x | x | x | 6 | 100% |

| [56] | x | x | x | 3 | 50% | |||

| [31] | x | x | 2 | 33% | ||||

| [57] | x | x | x | x | x | x | 6 | 100% |

| Total | 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| Authors | Ability to apply knowledge in practice |

Ability to learn | Ability to adapt to new situations | Ability to generate new ideas | Leadership | Commitment to one's sociocultural environment | Commitment to environmental preservation | Total SGC |

% SGC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [30] | x | x | x | 3 | 43% | ||||

| [53] | x | X | x | 3 | 43% | ||||

| [54] | x | x | 2 | 29% | |||||

| [55] | x | x | x | x | x | 5 | 71% | ||

| [56] | x | x | x | 3 | 43% | ||||

| [31] | x | x | X | 3 | 43% | ||||

| [57] | x | 1 | 14% | ||||||

| Total | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).