1. Introduction

Cambodia is an agrarian country, with a majority of the population residing in rural areas and relying on agriculture for food and income [

1]. The primary sources of food for the Khmer society are rice and fish [

2]. However, Cambodia is prone to natural disasters such as floods and droughts, which can devastate crops and disrupt food production. Climate change is exacerbating these risks, making it more challenging to ensure stable food supplies[

3]. The hydropower and infrastructure development in the Mekong River Basin has altered the hydrological regime of the Mekong River and Tonle Sap Lake (TSL), affecting fishery productivity and the food of the rural population[

4]. Land grabs and forced evictions have displaced communities from their traditional farming lands, disrupting their access to food sources and livelihoods[

5]. Poverty, lack of access to resources, and limited infrastructure contribute to food insecurity for many rural households [

6]. Furthermore, dependence on rice cultivation also poses risks, as it can leave households vulnerable to fluctuations in rice prices and yields[

7].

Rice holds a significant role as a staple food in Cambodia. Enhancing rice production and productivity is essential for improving food security in the country. Since 2015, the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) has been actively promoting rice production for export [

8]. The intensification of rice farming has led to an increase from one to 2-3 rice crops per year. As of 2023, annual rice production has reached 12 million tons, with approximately seven million tons being consumed domestically and the remaining five million tons available for export [

9]. Despite these advancements, a considerable portion of the population still grapples with food insecurity [

10]. Additionally, an estimated 45% of the population faces moderate or severe food insecurity [

11]. Despite the rise in rice production, food security remains a significant concern for the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) [

10,

12]. Therefore, this study aims to explore the reasons why food security issues persist despite the government program to increase rice production. The study involves a review of existing literature and an examination of food security in three provinces in the Cambodian Mekong Delta.

The Cambodian Mekong Delta (CMD) is a vital food-producing region that sustain livelihoods of many rural households. However, CMD faces several challenges, such as a growing population, development pressure, and climate change, which negatively affect the region's food environment, productivity, and food production [

13]. Furthermore, food security and nutrition continue to be significant concerns in the CMD, and are further exacerbated by natural shocks, an environmental degradation, and weak food system governance [

12].

2. Theoretical Framework of Food Security and Food System Governance

The food system encompasses the food system environments, production processes, governance, and distribution to consumers. It involves a wide range of actors and activities [

14,

15]. According to Ericksen [

16], the food system consists of the food system environments, drivers of food production, the food system activities, and the food system outcomes. Friend et al. [

17] emphasize that the food system, including the food system environments, food system activities, and food system outcomes, is undergoing change due to four driving forces: (1) actors and power; (2) discourse and narratives; (3) access to and control over productive resources; and (4) institutions. They highlight the role of actors' values, interests, and power in driving change within food systems. Additionally, actors use discourses and narratives to influence the interests of certain actors involved in systems change. Access to and control over key productive resources also play a significant role in driving change. Lastly, formal and informal institutional arrangements play a crucial role in mediating access and control of resources [

17] (

Figure 1).

The food system comprises sub-systems such as farming, water management, fishery, and aquaculture which interact with other crucial systems like energy, trade, and health to produce food [

14,

15]. Manhar et al. [

18] present two key sub-food systems: (i) natural and (ii) cultivated food systems. The natural food system encompasses rivers, lakes, forests, and mountains, which are valuable for accessing nutrient-rich foods, and can enhance households' resilience to unexpected events. So et al. [

19] present the Mekong River System as a natural food system, supllying fish and edible aquatic plants to feed millions of people in the Mekong Region. The Mekong River is a hugely productive fishery, estimated to yield some 2.32 million tonnes annually [

19], accounting for around 20% of global inland fish catch [

20]. The cultivated food system is quite diverse and includes various practices, such as farming, fruit and vegetable gardening, livestock raising, fishing and aquaculture. It is intimately connected to the wild natural food environment. Agriculture is a cultivated food system that produces staple crops as the primary food production, relying on land, fertilizer, seeds, and water. What is fascinating is how all these practices work together to provide us with a balanced diet and contribute to our food security[

21].

The food system activities encompass the production, distribution, and consumption of food products derived from agriculture, forestry, or fisheries, along with various related economic, societal, and environmental activities. Human manipulation of natural and cultivated food systems meets the dietary and other needs of humans. Furthermore, humans alter the natural food system to cultivate food through practices such as rice farming, fishing, livestock rearing, and vegetable growing [

16]. The food supply chains depend on interconnected ecological, human, energy, and economic systems to facilitate the production and distribution of food while sustaining livelihoods at all stages of the process from production to distribution [

15,

22,

23]. Multiple actors with different levels of influence, interests, values, and agency play a role in the production, distribution, and consumption of food. The activities within the food system are also shaped by ideologies, discourses, and narratives that validate or invalidate the interests of certain actors within the food system.

The activities within the food system play a crucial role in achieving food security outcomes [

22,

23]. Food security comprises four essential dimensions: (i) availability—ensuring an adequate and consistent food supply at the national or household level; (ii) accessibility—ensuring that individuals and households have the economic and physical means to obtain food, taking into account factors such as income, food prices, transportation infrastructure, and market access; (iii) utilization—ensuring that people can effectively utilize the food they have access to, including factors such as nutrition knowledge, food safety, sanitation, and access to clean water; and (iv) stability—ensuring that access to food is secure over time, not just in the present moment, and involves mitigating risks such as price volatility, natural disasters, conflicts, and other disruptions that can affect food availability and access [

22,

23]. Furthermore, the outcomes of the food system are influenced by the patterns of access to and control over key productive resources [

24]. Finally, formal and informal institutional arrangements play a crucial role in mediating access and control over resources, which in turn impact the outcomes of the food system [

25,

26,

27].

The discussion of food security often overlooks the "right to food," despite the central importance of the four elements. These elements do not encompass the legal interpretations of the "right to food," particularly omitting the aspects of 'agency' and 'sustainability' [

28]. Agency can be understood as the freedom to pursue important goals or values, extending beyond mere access to resources to include empowerment [

29]. This refers to individuals' capacity to improve their quality of life and participate in activities that influence broader societal frameworks, including the ability to voice opinions and impact policies [

30]. Sustainability, on the other hand, involves food system practices that sustain ecosystems in the long term, while interacting with economic and social systems to uphold food security and nutrition [

31,

32,

33].

The assurance of food security is a fundamental human right that plays a crucial role in promoting health, well-being, and sustainable development [

34]. The right to food goes beyond being fed during emergencies; it encompasses the right of all individuals to have appropriate legal frameworks and strategies in place to ensure access to an adequate food supply [

35]. Amartya Sen [

36] posits that food insecurity can persist even when agricultural yields are high, due to persistent low incomes among certain groups while others experience rising incomes. Achieving food security requires addressing fundamental issues such as poverty, inequality, inadequate infrastructure, environmental degradation, and conflicts. This involves promoting sustainable agriculture, improving nutrition, strengthening social safety nets, and enhancing resilience to external shocks [

37]. It encompasses the comprehensive governance of water, land, agriculture, fishery, irrigation, and natural resources management [

38], which are influenced by factors such as actors and power dynamics, institutions, discourses, narratives, and access to and control over resources in food system activities and outcomes [

39].

The food system involves various interactions, negotiations, conflicts, and cooperative decision-making processes related to food production, distribution, and consumption [

40,

41]. However, the governance of this system has been fragmented, often following a sectoral and top-down approach. Friend et al. [

17] emphasize the significance of fisheries in the Mekong River Basin as a food source for the people in the region. Unfortunately, fisheries have been overlooked in the food system, leading to the damming of the Mekong for electricity generation. In Cambodia, water management falls under the Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology (MOWRAM), whereas the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (MAFF) holds authority over rice production and fisheries, with no specific mandate concerning water resources [

42].

3. Materials and Methods

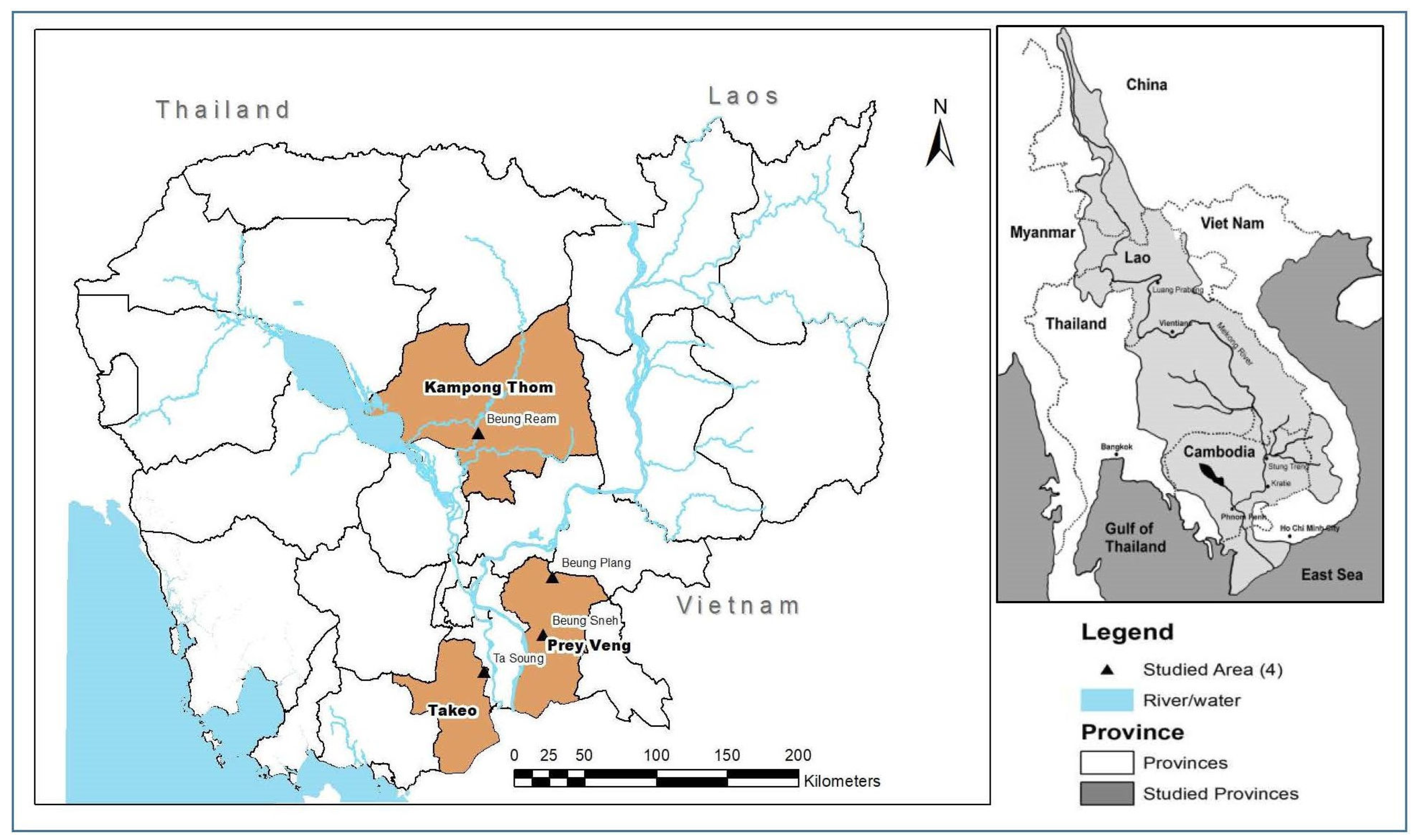

The conceptual framework described earlier provides a valuable tool for examining food system governance in CMD. The research is centered on three provinces in CMD: Prey Veng, Takeo, and Kampong Thom. Four specific sites have been chosen for studying food system governance in these provinces: Beung Sneh and Beung Phlang in Prey Veng, Ta Soung in Takeo, and Beung Ream in Kampong Thom Provinces (

Figure 2).

The research team utilized a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches to collect comprehensive primary and secondary data from the study sites. The team consisted of experienced members from renowned organizations such as WorldFish, the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), the Inland Fishery Research and Development Institute (IFReDI), and the Fishery Administration Cantonments (FiACs). The data collection process lasted from December 2022 to December 2023.

In the research process, both primary and secondary data were collected. Secondary data, which encompasses information gathered by others or existing previously, is typically obtained from sources such as books, journals, government publications, websites, databases, or other research studies. Researchers often use secondary data to complement their primary research or to analyze trends and patterns over time [

43]. On the other hand, primary data refers to original data collected directly from the source through methods such as surveys, interviews, experiments, observations, or questionnaires. This data is gathered firsthand by the researcher specifically for their investigation or study. Primary data is often used to address specific research questions or objectives and is considered more accurate and relevant to the particular research context compared to secondary data [

44].

The secondary data used in this study were sourced from various databases, including the commune database (2021) [

45], the Community Fishery (CFi) and Community Fish Refuge (CFR) databases (2022) [

46], and the Irrigation System Database (CISIS) [

47]. The secondary data collected focused on aspects such as population, irrigation, rice farming, farmlands, fish catch, pesticide, and fertilizer usage by farmers, and the number of CFis, CFRs, and Farmer Water User Communities (FWUCs). In addition to secondary data, primary data was collected through focus group discussions (FGD) and key informant interviews (KII). The FGDs involved FWUCs, CFRs, CFis, ID Poor 1&2, and non-ID Poor groups [

48], with each discussion group comprising five to seven participants.

Furthermore, Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) were carried out with various government agency representatives at the provincial level, including officials from the Provincial Departments of Water Resources and Meteorology (PDWRAMs), Provincial Fishery Administration Cantonments (FiACs), District Offices of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment (DANREs), Commune Councilors, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Prey Veng, Takeo, and Kampong Thom Provinces.

Table 1 provides an overview of the number of KIIs and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) conducted with CFis, CFRs, FWUCs, ID Poor 1&2, and non-ID Poor individuals in the study locations.

The research focused on assessing the collaborative efforts of Farmer Water User Committees (FWUCs), Community Fish Refuges (CFRs), and Community Fisheries (CFis) through Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) and Focused Group Discussions (FGDFs). Participants were also asked to provide insights into the impact of water usage by FWUCs on CFis/CFRs during three rice farming seasons, as well as the competition for water resources. The study emphasized the pivotal role of local authorities and proposed strategies to improve water management in the areas under study. Additionally, Focused Group Discussions (FGDs) were conducted with members of different communities to examine the changes in water resources, agriculture, fishery, and food over the past 10-15 years and to explore their effects on the communities. Interviewees shared their perspectives on the improvements in water resources, fishery, rice farming, food, and livelihoods resulting from the establishment of irrigation systems, FWUCs, CFis, and CFRs. The data collected from the FGDs, interviews, and secondary sources were analyzed using Excel, and the software generated percentages, figures, and tables. This quantitative data was complemented by qualitative information.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. The Siocio-economic and Geographical Conditions of the Cambodian Mekong Delta (CMD)

Cambodia has a total area of 181,035 km

2, and agricultural land occupies 4.5 million hectares, which accounts for 25% of the country's total land area [

49]. The country's wetlands cover about 30% of its land and are home to a vast freshwater fishery that includes migratory species in the Tonle Sap [

50,

51]. The Cambodian Mekong Delta (CMD), which spans 35,839 km2, excluding the Tonle Sap River's drainage basin and the Great Lake, is situated between the midpoint of Kratie and Kampong Cham provinces and the border of Cambodia and Vietnam. CMD comprises channels with a total length of 99 kilometers, which split into two rivers in Phnom Penh: The Mekong River on the left and the Bassac River on the right [

52]. The CMD includes four provinces - Prey Veng, Kandal, Takeo, and Svay Rieng. As of 2021, approximately 7 million people call CMD their home [

53].

The four provinces of CMD cover 14,591 km2, home to about four million or 25% of the total population. Agricultural land constitutes 72% of the total land, and 93% is for rice farming. The CMD contributes about 31% to the country's rice production. Prey Veng is among four CMD Provinces, covering 4,883 km2, of which agricultural land constitutes 79% of the total land area. The province comprises Cambodia's typical flat, wet region, enveloping rice fields and other plantations, and also encompasses one of the country's most significant rivers, the mighty Mekong. Also, Takeo is another CMD Province located in the southern region of Cambodia, bordered by Vietnam in the south, covering 3,563 km2, of which 74% of the total land area is agricultural. Last, Kampong Thom Province is located in TSL with a total land area of 13,814 km2, of which agricultural land constitutes 20%, and large areas fall in TSL.

The information provided in

Table 2 pertains to various waterbodies and irrigation schemes in the study area. Beung Sneh Lake (BSL) stands as the largest freshwater lake in Prey Veng. It is linked to the Mekong River and has a water storage capacity of 80 million m

3 during the rainy season. Furthermore, the Vaiko irrigation scheme, which spans across Prey Veng Province, is one of the largest in the country. Beung Phlang, a small waterbody connected to the Vaiko Scheme in Sithor Kandal District in Prey Veng Province, is also noteworthy. In contrast, the Prey Kabbas District in Takeo Province presents substantial potential for food production due to its extensive rice fields and floodplain connected to the Bassac River. Boeung Ream in Kampong Thom Province is another small waterbody in the Tonle Sap floodplain, linked to the Tang Krasaing Irrigation scheme constructed in 2015. Water from Beung Ream serves the purposes of rice farming and fisheries.

The sites under study provide shelter to roughly 19,205 households, spread across 72 villages. It is estimated that 60% of farming households are involved in rice farming, while approximately 24% of total households are engaged in fishing. However, the fishing population in Prey Kabbas District accounts for 33%, while in Beung Ream in Kampong Thom, fishing still employs around 30% of the total households. Nevertheless, about 19% of households in Prey Veng Province, including Beug Sneh are engaged in fishing. Poverty affects 15% of households in the study areas (

Table 2).

4.2. Food Systems

The CMD region relies heavily on rice farming and fishing as the primary food systems. With an abundance of river systems and expansive rice fields, the area yields a variety of produce such as rice, crops, vegetables, and livestock. The river system serves as a crucial water source for both wet and dry season rice farming as well as fisheries, ensuring a stable food supply for local communities. Rice cultivation near the river, known as 'srekrom' or lower rice fields, contrasts with 'sreleu' or upper rice fields, which depend on rainfall. The intermediate areas, referred to as 'Srekandal' or middle rice fields, rely on both river water and rainfall. Wet-season rice farming predominates in Sreleu, while dry-season rice farming takes place in Srekrom and Srekandal, with wet-season farming comprising 71% of the total farming areas and dry-season farming representing 29% (

Figure 3).

Between May and October, the BSL area experiences rainfall and receives water from the Mekong River, leading to an increase in water levels and causing flooding in the Srekrom (lower rice fields) with a depth of approximately 1-2 meters, making it unsuitable for rice cultivation. The Srekandal (middle rice fields) are also submerged with an estimated depth of less than 0.5 meters. However, the rising water level does not reach the Sreleu (upper rice fields), but the rainwater flows into these fields, allowing farmers to cultivate rice between May and October. Subsequently, the water begins to recede from BSL around November and goes back to the Mekong River. Farmers then start growing rice during the recession period in the Srekrom and use the remaining water in the BSL to water the rice fields.

During the rainy season, the water level in the Prek Ambel River (PAR) in Prey Kabbas District, Takeo Province, rises due to the increasing water level in the Bassac River. Around 60% of the farmland is submerged in river water for approximately six months, rendering it unsuitable for WSRF but ideal for DSRF, also known as Srekrom. The remaining 40% of farmland, Sreleu, remains unaffected by flooding, allowing farmers to cultivate WSRF using rainfall as their primary water source. As the dry season arrives, the water recedes from the PAR floodplains, enabling farmers to cultivate the recessions or DRSF. Each household is granted 2 hectares of land, but 31% of households in the area are landless and resort to fishing to supplement their incomes.

The region of Beung Phlang is situated in the Mekong floodplain and is prone to frequent river flooding. Due to the implementation of irrigation systems, the frequency of these floods has decreased, allowing local farmers to cultivate only WSRF. On the other hand, Beung Ream is located within the floodplain of TSL, which regularly experiences flooding from the flood pulse of Tonle Sap. This area is rich in fishery and sediments that are beneficial for agriculture. The farmland in Beung Ream has been divided into Sreleu, Srekandal, and Srekrom. However, farmers cultivate only WSRF in Sreleu and Srekandal, neglecting Srekrom due to the high production costs and low yields.

Fishing is supplementing foods for households, which is a source of protein. However, fishing is small-scale for household consumption and uses small-fishing gears. Approximately 24% of the total population is engaged in fishing, but the fishing population in Ta Soung community constitutes 33%, higher than other communities. In Beung Ream, fishing supplements around 30% of the population's food requirements, whereas in BSL and Beung Phlang, fishing sustains approximately 19-20% of the local population (

Table 2).

4.3. Food System Activities

4.3.1. Food Production

Water resources are available throughout the year but vary by month, depending on rainfall and water flows from the Mekong River. These resources have been extensively utilized for agriculture, particularly rice farming. Traditionally, Cambodian agricultural households cultivate Wet Season Rice Farming (WSRF) with native rice varieties, yielding 2-3 tons per hectare for household consumption, with only one crop per year. In 2015, the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) initiated a national program to rehabilitate irrigation schemes nationwide to support rice farming and implemented a policy to promote rice exports. Consequently, Cambodian agricultural households have increased rice farming seasons to 2-3 times a year, using irrigated water for Wet Season Rice Farming (WSRF) and the first and second dry season rice farming (DSRFs).

Despite ongoing efforts, farmers continue to face challenges due to low prices and a limited market for their rice products. Notably, Vietnam has been actively promoting rice exports and engaging in paddy rice trade with Cambodia, enabling Cambodian farmers to sell their rice to Vietnam. Vietnamese traders have been assisting Cambodian farmers who are interested in entering the rice trade by introducing them to specific rice strains and encouraging the cultivation of high-yield Vietnamese rice varieties, including IR504 and OM5451 (refer to

Table 3). Consequently, farmers in the study areas of Cambodia have adopted Vietnamese rice varieties such as WSRF and DSRFs and have been trading them with Vietnam

Agricultural households have increasingly transitioned from traditional rainfed rice farming to irrigated agriculture, notably embracing the dry season rice farming (DSRF) method. This shift has entailed a departure from transplanting to broadcasting as the predominant rice farming approach. In addition, there has been a notable shift from labor-intensive techniques to mechanized rice farming and from subsistence farming to commercial activities. Tractors have now supplanted draft animals for plowing rice fields, and hired labor is commonly engaged for tasks such as rice broadcasting and the application of agrochemical inputs such as fertilizers and pesticides. Threshing machines are also employed during the harvest. These changing farming practices have led to some farmers being commonly labeled as "sethei kasekor" or "tycoon farmers," as they predominantly rely on hired assistance and services to manage their farming operations and generate profits.

Over time, farmers in various studied sites have made significant progress in their agricultural practices. Instead of using traditional irrigation methods and transplanting rice, they now utilize irrigated water and broadcast rice. Additionally, they have shifted towards mechanized rice farming, which is less labor-intensive and more beneficial for trading purposes. The number of tractors used in Prey Veng Province for plowing increased from 678 tracktors in 2014 to 2,446 in 2018. Kampong Thom has also seen a rise in tractor usage from 589 to 1,322 during the same period. These changes are also taking place in Takeo Province. In addition, harvesting machines have become a common tool for farmers to gather paddy rice. In Prey Veng, the number of harvesting machines increased from 464 in 2014 to 1,053 in 2018, while Kampong Thom increased from 130 to 342 machines during the same period. However, the number of harvesting machines has decreased in Takeo. The cost of hiring a harvesting machine, which includes packing, is approximately USD100/ha.

The introduction of high-yield rice strains has led to an increase in fertilizer and pesticide usage. Around 73% of households within the study regions apply chemical fertilizers for rice farming year-rounds. A 50kg bag of fertilizer costs approximately USD30, resulting in an expenditure of USD150-210 per hectare for fertilizer use. The chemical fertilizers are traded across orders from Vietnam to Cambodia and are readily available for purchase. Despite their accessibility, farmers have a limited understanding of the appropriate use of fertilizers (

Table 3).

Approximately 70% of farming households utilize pesticides throughout the rice farming seasons. This typically involves applying pesticides 3-4 times per hectare until the rice has been harvested, with each application costing approximately USD34/ha. Each farming household can expect to spend between USD105-140/ha for pesticide uses, including the labor fees. Unfortunately, the use of pesticides has detrimental effects on aquatic life, such as fish, resulting in a decline in their population. Additionally, invasive snails can cause damage to paddy rice, highlighting the critical need for proper protection.

The cultivation of three rice crops annually by farmers requires a significant amount of water. However, only 19% of farming households have access to irrigation systems. In Ta Soung, BSL, and Kakoh Commune/Beung Ream, approximately 26%, 18%, and 17% of agricultural households, respectively can use irrigated water for rice cultivation. Interestingly, about 42% of farmlands are irrigated during the dry season, while only 24% receive irrigation during the wet season. Water fees for irrigation range from USD 67-75/ha, with gravity-fed water costing approximately USD 63/ha and pumping costs ranging from USD 75-87/ha. In Ta Soung, water fees are set by the FWUCs based on expenses incurred in using electricity to pump water from the Prek Ambek River (PAR) into the irrigation canals, typically ranging from USD 50 to USD 65 per hectare.

Farmers in Beung Sneh and Beung Ream only pay water fees for the 1st DSRF between November and January because they receive sufficient water for irrigating their rice fields. They do not pay water fees for the WSRF between May and October as they depend on rainfall for rice cultivation. However, during the 2nd DSRF, between February and April, there were water shortages. Approximately 50% of water users pay fees for water usage, but due to the practice of growing three rice crops annually, water use has reached a critical level. To irrigate DSRFs, farmers have resorted to pumping water from nearby sources like rivers, ponds, and lakes, with each household owning at least one water-pumping generator. Unfortunately, this has led to intense competition among farmers to pump water for irrigation, negatively impacting fisheries and aquatic systems.

4.3.2. Food Consumption

Rice is the primary staple food in Cambodia and a daily dietary staple for rural households. Fish is the second most consumed food, typically eaten five days a week by agricultural households. In addition, wet-season rice farming primarily caters to household consumption, utilizing local varieties. To maximize the amount of rice available for sale, agricultural households tend to limit household consumption. During the first DSRF, farmers sold nearly all rice produced to rice traders from Vietnam. During the second DSRF, potential water scarcity due to climate change and competition for water resources among farming households raise more concerns about rice yield. These could have adverse impacts on rice yields and its production, leading to a reduction in overall rice production towards the end of the season and significant losses. As a result, household rice consumption may also decrease.

The current trend shows an increase in rural-urban and overseas migrations, alongside a growing rural rice production economy in the rural communities. With higher migration rates, many rural households are adapting to new food consumption practices, including the consumption of fast foods, instant noodles, and beverages. Consequently, farmers rely more on markets to meet their food and household needs, as they are occupied with three rice crops a year and have limited time to grow their vegetables. Each agricultural household spends 30,000 riels daily to purchase vegetables, meat, and household items from the market.

Fish is a second food item, consumed almost daily by rural households. In Prey Veng, about 88% of households consume their fish catch, followed by 83% in Kampong Thom and 77% in Takeo. On the other hand, about 14.6% of fish caught by households in Cambodia was sold, of which 22% in Takeo Province, 17% in Kampong Thom, and 11% in Prey Veng [

54]. Nevertheless, a study found that despite nearly 76% of households not participating in fishing activities, they still consume fish five days per week. Agricultural households typically purchase their fish from local markets. However, some villagers have expressed that local fish catch is not enough for sale in local markets, leading them to rely on fish imported from outside their communities. Moreover, agricultural households in Prey Veng and Takeo Provinces living near the Vietnam-Cambodia border have reported consuming raised fish, most likely imported from Vietnam.

4.3.3. Trading

Rice is primarily cultivated for household consumption during the wet season using local strains like Malis and Neangming. However, farming households move to cultivate DSRF solely for sale. Thus, high-yield rice varieties, IR504/OM5451, from Vietnam are favorable to local farmers in Cambodia due to their high market demands, value, yield, and water availability. Despite this, the high market demand for Vietnamese rice varieties means that Cambodian farmers are more inclined to sell them than to consume them. Also, this has gradually pushed WSRF practices towards more high-yield and high-value rice varieties from Vietnam.

The DSRF is generally viewed by farmers as a significant source of income from rice trading. Vietnamese rice varieties are specifically grown for trading purposes. The price of these rice varieties has significantly increased in the last three years, ranging from 800 riels in 2020 to 1,200-1,400 riels in 2023, compared to 300 to 600 riel per kg in 2005. Nationally, around 39% of agricultural households are involved in rice farming activities for trades, with the highest percentages in Prey Veng at 42.3%, followed by Kampong Thom at 39% and Takeo at 21% [

54]. Approximately 20.3% of agricultural households indicate that rice farming contributes 60-100% of their total household income. Kampong Thom has the highest percentage of households (26.1%), where agriculture contributes 60-100% of their total income, followed by Takeo (21.3%) and Prey Veng (17%).

It is important to note that almost all households engage in DSRF for sale and WSRF for consumption, according to the studies. The study found that tons of fish are imported by traders into Cambodia from Thailand and Vietnam through various border crossings. In Prey Veng, the unconfirmed report estimates that about 50 tons of fish daily are imported from Vietnam and sold in local markets. In Kampong Thom Province, about 70 tons/day of fish are imported to sell in local markets. The price of imported fish from Vietnam is about 4,000 riels/kg, cheaper than the Cambodian-raised fish, but the taste is not that good compared with Cambodia’s fish. The Kingdom imported 130,000 tons of seafood in 2019.

4.4. Food System Outcomes

Rice farming has undergone a significant transformation with the adoption of 2-3 crops per year, which coincides with an increase in migration rates. In the study areas, about 24% of the total population above 18 years old migrate to seek employments in cities and overseas. A female migration constitutes 19% of the total female population. Of the female migrants, approximately 2% are young individuals who migrate overseas. Notably, BSL has the highest migration rate at 32%, followed by Beung Ream at 20% and Ta Soung at 13%. Furthermore, BSL also has a higher percentage of female migration, at 26%, compared to Ta Soung at 11% and Beung Ream at 10%. These have contributed shortages of labors in the agriculture (

Table 3).

To maintain or increase the rice farming seasons, agricultural households hire labors and practise agricultural mechanizations. These have increased the cost of rice prodution. The rising cost in rice farming has had a substantial impact on the profits of many farmers. Many farming households have turned to formal and informal money lenders to secure the necessary funds. In fact, over 70% of agricultural households in Beung Phlang and Ta Soung are currently in debt, while in Beung Ream and BSL, the numbers are 60% and 56%, respectively (

Table 3). Consequently, farmers often seek the assistance of Micro Finance Institutions (MFIs) to fund the rice farming industries and purchase essential equipment and supplies.

It has been observed that young people are increasingly migrating to urban areas, which may make it difficult for them to return to their rice fields. As a result, farmers may opt to sell their land to private owners or companies, and some may choose to lease their land back from these companies to continue farming. In Beung Phlang, for example, a substantial number of agricultural households sold their farmland to the owners of brick factories, who then turned the purchased agricultural lands into brick industries. Many villagers ended up working for with brick industries as laborers. In Samnak village, located in Kakoh Commune in Kampong Thom Province, 50% of 312 households sold their Srekrom (lower rice fields) to a company for two thousand US Dollar per hectare. Approximately 70 hectares of agricultural land in the village are classified as Srekrom. Currently, around 20 households have no farmland of their own and lease land from a company to cultivate rice farming for $100 per hectare per farming season. In the neighboring village of Santuk Krao, approximately 250 hectares of Srekrom have been sold to a private company, and similar circumstances have happened in other villages within Kakoh Commune.

The rise in rice farming and extended farming seasons has resulted in an increased water demand. This has led to competition among farmers for water resources to irrigate the 1st and 2nd DRSFs, resulting in depleted water sources in Beung Ream, BSL, and Beung Phlang. Consequently, water conflicts have arisen among farmers in these areas. Also, there have been water conflicts between farmers and fishers. For instance, in BSL and Ta Soung, FUWCs extract water resources to irrigate rice farming, while CFis protect water to keep the fishery productive for fishing households. In Beung Ream and Beung Phlang, CFRs protect the natural ponds and keep fisheries, while FUWCs compete for water for rice farming. These caused water depletions and conflicts.

The rice farming industry has had a notable impact on local fisheries, with canals, ponds, and streams being drained to the point of depletion. Additionally, the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides has also harmed aquatic life. Regrettably, the irrigation management system does not prioritize fisheries, resulting in a decline in rice field fisheries, as reported by farmers. In BSL, 44 villages with approximately 2,000 households rely on fishing, with an average catch of 1.5kg daily. Beung Phlang sees 248 households fishing during the wet season, with an average catch of 2kg per household daily. The Prek Ambel River (PAR) in Ta Soung in Prey Kabbas District was a former fishing lot covering 6,673 ha, leased to an owner for 46 million riels, or USD 11,500 annually. The former fishing lot areas have now been transformed into four Community Fisheries (CFis) with the participation of 1,200 households from four communes in Prey Kabbas District in Takeo Province. Despite this, the fishery has declined, and the average catch remains around 2kg per household daily. Lastly, in Beung Ream in Kampong Thom Province, about 1,000 households benefit from fishing during the three-month high fishing season, with an average catch of 2kg per household per day.

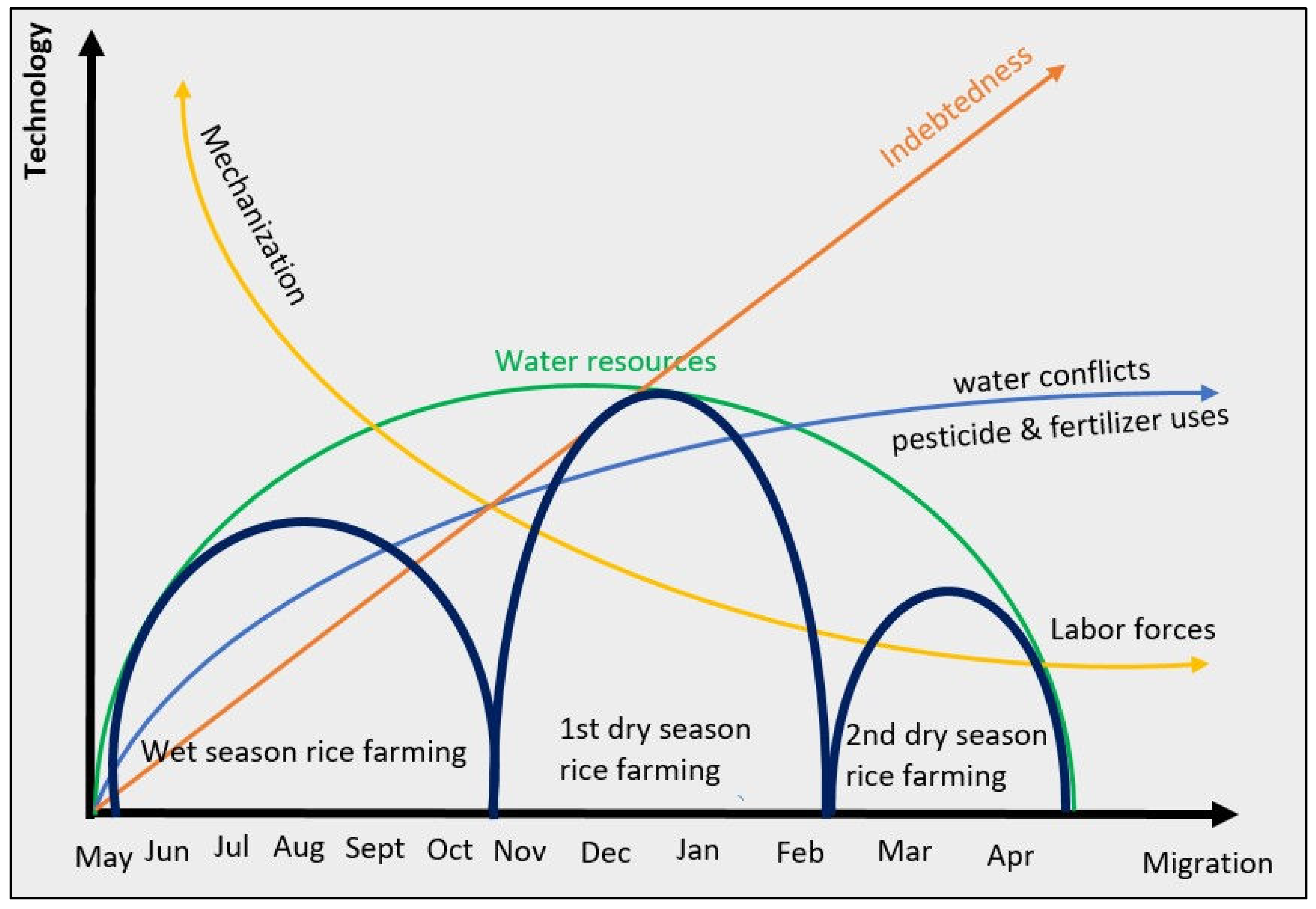

Figure 3 simplifies the current farming situations in the studies areas and the challenges farmers face in farming. Water resources for the whole year are limited, varied by months, increasing from May onward as a result of more rains, and peak in October or early November but drop significantly from January to April. Traditionally, farming was on rice crop a year, from May to November, and the cultivation period is six months with an average yield of 3 tons/ha. At present, rice farming has been increased to 2-3 times a year—(1) wet season rice farming (WSRF) from May to October; (2) the 1

st dry season rice farming (DSRF) from November to January and (3) the 2

nd DSRF from February to April. Farmers have competed for water resources to irrigate three rice crops per year, leading to water shortages, spoiling rice farming, and water conflicts between farmers and farmers and between farmers and fishers. Migration has happened almost everywhere in the rice farming communities in Cambodia, leading to a shortage of labor. In response, farming households practice farming mechanization, leading to a high cost of production. To do so, farming households take loans from Microfinance institutions and money lenders to finance the rice farming business, ending up in heavy indebtedness. Farmers have also used agrochemical inputs, including pesticides and fertilizers, to improve rice productivity. They are harmful to aquatic animals and fisheries and it also increases the cost of production.

4.5. Actors, Formal and Informal Institutions and Controls over Resources

Food production involves a complex integration process of putting water, land, and natural resources into the production, and the supplies of labor, technology, and capital by local communities or the food production actors into the food production system. While state agencies support food production, processing, consumption, and trade, the governance of the food system remains sectoral, technical, and centralized.

Water plays a critical role in food production, particularly in agriculture, and its management is overseen by MOWRAM. Currently, water management is primarily focused on irrigation, and four irrigation schemes have been implemented in the study areas, covering a total area of 166,790 hectares. Furthermore, MOWRAM and PDOWRAM have established four FWUCs to support the irrigation schemes, with approximately 15,481 families actively involved in these organizations. These FWUCs obtain water from a variety of sources, including BSL, the Mekong River, the Prek Ambel River (PAR), and the Stung Chinit River.

The management of irrigation schemes and FWUCs is centralized under MOWRAM, with PDOWRAMs responsible for handling technical matters at the provincial level and providing reports to the Provincial Government on planning, management, and the integration of irrigation planning into provincial planning and budgeting. PDOWRAMs collaborate with the District Office of Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Environment (DANREs) to supervise irrigation schemes and FWUCs. DANREs are responsible for water resource management and collaborate with FWUCs to operate the irrigation systems, providing progress updates to PDOWRAMs. FWUC leaders communicate with DANRE Officers to authorize water release for rice field irrigation and progress updates are reported to PDOWRAM. At the end of the farming season, FWUC members pay water fees as stipulated in their by-laws. It is important to note that fisheries are not currently part of FWUCs or the management of irrigation schemes.

In contrast, the management of fisheries in the studied areas is centralized under the FiA, which has established both CFis and CFRs [

55] to oversee this important resource. Across the region, eight CFis and two CFRs have been put in place, with the latter linked to rice fields, fisheries, and irrigation systems. CFis, on the other hand, are situated in water bodies to manage and protect inland fishery resources. These bodies work tirelessly to maintain water levels that are deep enough to shelter fish, especially during the dry season, to ensure their conservation. However, as the actions of CFis and CFRs often come into conflict with those of FWUCs, the pressure on these organizations is immense. The need for farmers to pump water by FWUCs from rivers, lakes and ponds to irrigate their paddy fields directly contradicts the actions of CFi and CFR conservations, leading to a reduction in water volumes and levels that can negatively impact the fisheries. Additionally, CFis and CFRs also face the threat of flooded forest destruction, following the decline in water level.

The FiA has established both CFis and CFRs, which are registered with MAFF. Management of these areas at the provincial level falls under the jurisdiction of FiACs, although FiACs are not directly under the FiA. Instead, they are under the control of the Provincial Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery (PDAFF). Unfortunately, CFis and CFRs have become inactive due to insufficient support. They encounter several challenges, including infringements into the protecting fishery areas, illegal fishing practices within CFis and CFRs, inadequate involvement from local members and non-members in managing and protecting fishery resources, and insufficient support from concerned agencies. There have also been conflicts between CFis and CFRs, and FWUCs over the pump of waters from waterbodies to irrigate paddy fields; the overlapped physical spaces between CFis and CFRs and FWUCs; the weak fishery governance in irrigation schemes and FWUC areas, and the uses of agro-chemical inputs such as pesticides and fertilizers in rice farming that harm fish and other aquatic animals [

56]. Furthermore, the lack of financial capitals and technical support from FiA, FiACs, and local government, as well as donors and development partners in managing CFi and CFR areas hinder the conservation and protection of fish and other aquatic animals and its habitats.

In addition, other natural resources management communities have been organized in the study areas. Tuolporn Taley Boeung Sneh in BSL is home to approximately 50 bird species. The Ministry of Environment (MoE) has issued a sub-decree to designate BSL as a multiple-use area covering 3,557 hectares [

57]. Moreover, the bird sanctuary in BSL, spanning 86 hectares, was established by the MoE in 2019. The MoE has also created a community-based ecotourism (CBET) program that allows tourists to visit the bird sanctuary and engage with local communities in conservation efforts. Two villages, Torp Sdach and Kampong Sleng [

58], have joined in establishing ecotourism. The CBET offers tourist services such as boat tours, food and beverage, and seating platforms. The Ministry of Tourism and the Provincial Department of Tourism of Prey Veng support the CBET and ensure that it operates by the Ministry's legal and institutional frameworks.

However, there are overlapping roles and responsibilities between MOWRAM/PDWRAM, MOE/PDOW, MAFF/PDAFF, and FiA/FiACs in the management of the same spaces but different specializations and sectors from national and local levels, for instance, the BSL and Ta Soung Communities. These have burdened local communities such as FWUC, CBET, CFis, and CFRs to manage their areas. Different community-based organizations have obeyed specific rules and regulations from central ministries down to the provincial departments and then imposed them on local communities, creating inevitable tensions and conflicts. However, they live in the same villages, drinking water and eating fish and rice from the same lake, ponds, and rice fields. These have undermined the food productivity of the landscapes and the communities.

5. Conclusions

Cambodian rice farmers have enhanced rice farming from one to 2-3 rice crops annually. Also, the rice yield has increased from 2-3 tons to 5-6 tons per hectare. Rice production increased by 17% between 2015 and 2019, with annual average rice production of 10.32 million tons [

12] and 11.62 million in 2022 [

49,

59]. Cambodia has generated a rice surplus of more than 6.3 million tons annually for export [

49]. A well-known government figure from MAFF, said, “Cambodia enjoys favorable food security, even though some countries faced food security issues after India stopped exporting white milled rice…The key factors conducive to food security in Cambodia are that the country is a paddy producer with a surplus of more than six million tons per year” [

60].

The concept of food security is multifaceted, encompassing the fundamental right to food and six key dimensions: availability, access, utilization, stability, agency, and sustainability [

61]. These dimensions are reflected in the access to essential resources such as water, land, agriculture, and fishery resources, which are essential for establishing CFis, CFRs, and FWUCs that secure access to these vital resources for rice farming and fishery production. Thanks to irrigation systems, agricultural households can cultivate rice farming three times per year, increasing rice production for many rural households. However, policies that prioritize rice exportation may not always align with the goal of food security, as private sectors may encroach on state and private lands for rice farming, leading to land conflicts, as reported by the Human Rights Group [

62]. Additionally, with an average landholding size of 1.35 hectares per household, as found in this study and consistent with the ADB report in 2021, agricultural households may struggle to produce a large export surplus in the context of increasing climate change, migration and labor shortages.

RGC announces the increase in total volumes of paddy production, which contribute to achieve the rice export policy. Nevertheless, the increased paddy production among farmers does not clearly view to contribute to the Cambodia's rice export policy. Instead, Cambodian farmers cultivate Vietnamese rice varieties that are introduced by Vietnamese rice traders, and sell them back to Vietnam through Vietnamese traders, which at the end serve the Vietnamese rice export business to the global markets. On the contrary, Cambodian farmers suffer from price instability and prices set by the Vietnamese traders.

The rise of rice farming, with its potential for 2-3 farming seasons per year, has coincided with an increase in labor migration. The migration has led to a labor’s shortage in the agricultural sector in Cambodia, with approximately 1,301,609 young workers, or roughly 8% of the total population, choosing to migrate to seven different countries across Asia. Thailand alone attracts around 1.2 million workers, not including those who are undocumented [

59]. In the studied areas, only 2% of adults above 18 years old migrate overseas, which is a relatively low number but is increasing. Meanwhile, domestic migration found in this study makes up around a quarter of the total population. These trends have resulted in a reduction in the labor force available for rice farming.

However, agricultural households have responded by intensifying their rice farming efforts. Firstly, they have mechanized farming processes by hiring tractors, harvesting, and threshing machines to plow, broadcast, and harvest their rice fields. Some farming households have even hired laborers to work on their farms [

63]. Secondly, rice intensification has been achieved through the increased use of agrochemical inputs to boost yields. Thirdly, local rice varieties have been substituted with higher-yielding varieties imported from Vietnam for trade with Vietnamese traders. The majority of agro-chemical inputs such as fertilizers and pesticides utilized in rice farming industry in southeastern Cambodia are imported from Vietnam. These findings are consistent with other studies. Cambodian farmers could access to fertilizers and pesticides borrowed from Vietnamese merchants, with the agreement to sell the harvested paddy to repay the debts. Vietnamese traders charge an interest rate of up to 2% per month [

64].

The rising cost of farming has become a burden on households, leading many to seek financial assistance through microfinance. The report of Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LICADHO) [

65] confirmed that, by the end of 2019, over 2.6 million Cambodian borrowers had a total of

$10 billion in microfinance debt, with an average loan size of

$3,804. This accounts for approximately 16% of the total population. Frank's study [

66] on microfinance in Cambodia (2022) indicates that about 55.5% of the population takes loans from microfinance, and this percentage may have increased since the study. The Cambodia Agriculture Survey (CAS) in 2020 [

42] found that around 21.3% of farming households borrow money from microfinances for rice farming. In certain provinces, such as Prey Veng, Kampong Thom, and Takeo, borrowing rates range from 12% to 20% [

66]. Notably, in Takeo Province, around 70% of farmers take out small loans between USD 250-1500 [

67]. Comparting with other studies, this study found slighly high percentage of indebtedness of around 60-80% of the total population. The LICADHO and Equitable Cambodia (2020) [

68] indicate that "debt levels in Cambodia have already reached unsustainable levels," with communities reporting that they are eating less food and borrowing from private lenders to repay microloan debts. Selling farmland to repay loans and renting it from landlords at USD100 per hectare to continue farming is also prevalent among some agricultural households. This over-indebtedness crisis has raised serious and urgent questions about its impact on children, including child labor, dropping out of school, and widespread land sales.

Cambodia's focus on rice trade and cultivation has led to neglecting local rice varieties and increasing reliance on Vietnam for rice farming and trade [

69]. Usually, the wet-season rice is cultivated by farming households for household consumption and the dry-season rice farming is cultivated mainly for trade to Vietnam [

64]. However, due to high demand, wet-season rice farming has also shifted towards trade. Additionally, agricultural households have started consuming more Vietnamese rice varieties, which could have significant long-term implications.

The intensification of rice farming has led to increased irrigation development. MOWRAM has developed the Water Sector Strategic Development Plan (WSSDP) 2019-2033 to rehabilitate the irrigation system across Cambodia. To do so, MOWRAM needs a budget of USD 3.15 billion. The RGC allocated USD472 million to MOWRAM to implement the WSSP 2019-2023 to rehabilitate the irrigation system to support the agricultural development and improve rice production for export [

70]. The increased irrigation system rehabilitation in Cambodia contributed to the increase in annual rice production of up to 40% [

1]. Despite that, the increased climate change has made the water available uncreditable for rice cultivation. The increased water use for rice farming across three farming seasons has led to water shortages, which could lead to water tensions among farmers. Also, increased water use for rice farming would affect fishery aquatic resources and biodiversity.

Effective water governance is crucial for the success of rice farming, fishery management, and irrigation development. Unfortunately, this has not been easy to achieve due to sectoral and centralized systems that prioritize the interests of specific agencies. For example, MOWRAM dictates the roles and responsibilities of Farmer Water User Communities (FWUCs) according to Water Laws and Sub-decrees without considering the perspectives of other agencies like MAFF, FiA, and provincial government. As a result, FWUCs tend to focus on irrigating rice fields by extracting water from water bodies, while Community Fisheries (CFis/CFRs) prioritize protecting water sources for their fisheries. However, climate change has made water availability more unpredictable than ever before. Weak water governance and poor coordination between MOWRAM, MAFF, FiA, and provincial government agencies in water infrastructure development, water use, and conservation create additional vulnerability for water availability for rice farming in the face of altered hydrological regimes in the Mekong River and climate change. These could ultimately compromise food production and consumption at the sub-national level [

71].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., S.d.S. and H.K.; Methodology, M.S., H.K. and H.S.; Formal analysis, M.S.; Investigation, M.S., S.S., S.d.S., H.K., T.T. and H.S.; Resources, S.d.S.; Data curation, S.S., C.K., T.T. and H.S.; Writing—original draft, M.S., S.S., S.d.S. and H.K.; Writing—review & editing, M.S., S.d.S. and H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.