Submitted:

09 June 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Flourishing

1.2. The 24 Character-Strengths

1.3. Positive Solitude

1.4. The Current Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Acknowledgments

References

- Bachman, N., Palgi, Y., & Bodner, E. (2022). Emotion regulation through music and mindfulness are associated with positive solitude differently at the Second Half of Life. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 46, 520–27. [CrossRef]

- Baumann, D., Ruch, W., Margelisch, K., Gander, F., & Wagner, L. (2020). Character strengths and life satisfaction in later life: An analysis of different living conditions. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15, 329-347.

- Burger, J. M. (1995). Individual Differences in Preference for Solitude. Journal of Research in Personality, 29, 85–108. [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L. L., Fung, H. H., & Charles, S. T. (2003). Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motivation and Emotion 2003, 27, 103–123. [CrossRef]

- Coplan, Robert J., Hipson, W. E., Archbell, K. A., Ooi, L. L., Baldwin, D., & Bowker, J. C. (2019). Seeking more solitude: Conceptualization, assessment, and implications of aloneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 148, 17–26. [CrossRef]

- Coplan, Robert J., Ooi, L. L., & Baldwin, D. (2019). Does it matter when we want to be alone? Exploring developmental timing effects in the implications of unsociability. New Ideas in Psychology, 53, 47–57. [CrossRef]

- Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1994). Set like plaster? Evidence for the stability of adult personality. In T. F. Heatherton & J. L. Weinberger (Eds.), Can personality change? (pp. 21–40). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Dall, T. M., Gallo, P. D., Chakrabarti, R., West, T., Semilla, A. P., & Storm, M. V. (2013). An aging population and growing disease burden will require a large and specialized health care workforce by 2025. Health Affairs, 32, 2013-2020. . [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (Ed.). (2009). Assessing well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener (Vol. 37). Springer Netherlands..

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276. . [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D. W., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97, 143-156. [CrossRef]

- Gerino, E., Rollè, L., Sechi, C., & Brustia, P. (2017). Loneliness, resilience, mental health, and quality of life in old age: A structural equation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2003..

- Gradišek, P. (2012). Character strengths and life satisfaction of slovenian in-service and pre-service teachers. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 2, 167-180..

- Goossens, L. (2013). Affinity for aloneness in adolescence and preference for solitude in childhood: Linking two research traditions. The Handbook of Solitude: Psychological Perspectives on Social Isolation, Social Withdrawal, and Being Alone, 150–166. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis 2nd ed.: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, L. W., Knight, T., & Richardson, B. (2013). An exploration of the well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic behaviour. Journal of Positive Psychology, 8, 322–336. [CrossRef]

- Heintz, S., & Ruch, W. (2022). Cross-sectional age differences in 24 character strengths: Five meta-analyses from early adolescence to late adulthood. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 17, 356-374. [CrossRef]

- Hutteman, R., Hennecke, M., Orth, U., Reitz, A.K., & Specht, J. (2014). Developmental tasks as a framework to study personality development in adulthood and old age. European Journal of Personality, 28, 267–278. [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 207-222..

- Koch, P. J. (1990). Solitude. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, 181–210.

- Koch, P. J. (1994). Solitude: A philosophical encounter. Open Court Publishing.

- Larson, R. W. (1990). The solitary side of life: an examination of the time people spend alone from childhood to old age. Developmental Review, 10, 155–183. [CrossRef]

- Larson, R. W. (1997). The emergence of solitude as a constructive domain of experience in early adolescence. Child Development, 68, 80–93.

- Long, C. R., Seburn, M., Averill, J. R., & More, T. A. (2003). Solitude experiences: varieties, settings, and individual differences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 578–583. [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, C., Bore, M., & Munro, D. (2008). Values in action scale and the Big 5: An empirical indication of structure. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 787-799. . [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C. S., Karaoylas, E. C., & Starzyk, K. B. (2018). Lifespan differences in a self determination theory model of eudaimonia: A cross-sectional survey of younger, middle-aged, and older adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 2465-2487. . [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R. E. (2014). Scale- and Item-Level Factor Analyses of the VIA Inventory of Strengths. Assessment, 21, 4–14. [CrossRef]

- Myers, J. E., Sweeney, T. J., & Witmer, J. M. (2000). The wheel of wellness counseling for wellness: A holistic model for treatment planning. Journal of Counseling and Development, 78, 251–266. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L. J. (2013). Going it alone: Comparing subtypes of withdrawal on indices of adjustment and maladjustment in emerging adulthood. Social Development, 22, 522–538. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. T., Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2021). The possibilities of aloneness and solitude. In R. J Coplan, J. Bowker, & L. Nelso (Eds.), The Handbook of Solitude. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, R. M. (2020). Six functions of character strengths for thriving at times of adversity and opportunity: A theoretical perspective. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15, 551-572. . [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, J., Rupprecht, F. S., & Ristl, C. (2022). Experiences of solitude in adulthood and old age: The role of autonomy. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 46, 510-519. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality and Quantity, 41, 673–690. [CrossRef]

- Ost Mor, S., Palgi, Y., & Segel-Karpas, D. (2020). The definition and categories of positive solitude: older and younger adults’ perspectives on spending time by themselves. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 009141502095737. [CrossRef]

- Palgi, Y, Segel-Karpas, D., Ost Mor, S., Hoffman, Y., Shrira, A., & Bodner, E. (2021). Positive solitude scale: theoretical background, development and validation. Journal of Happiness Studies 2021, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Pauly, T., Lay, J. C., Nater, U. M., Scott, S. B., & Hoppmann, C. A. (2017). How we experience being alone: age differences in affective and biological correlates of momentary solitude. Gerontology, 63, 55–66. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, ME (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press. .

- Peterson, C., Ruch, W., Beermann, U., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. (2007). Strengths of character, orientations to happiness, and life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2, 149-156. [CrossRef]

- Ren, D., Wesselmann, E. D., & Van Beest, I. (2021). Seeking solitude after being ostracized: A replication and beyond. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47, 426–440. [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: a eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 13-39.. [CrossRef]

- Saarikallio, S. H. (2012). Development and validation of the brief music in mood regulation scale (B-MMR ). Music Perception, 30, 97–105. [CrossRef]

- Shoshani, A. (2019). Young children’s character strengths and emotional well-being: development of the character strengths inventory for early childhood (CSI-EC). The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14, 86-102. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. J., & Caetano, A. (2013). Validation of the flourishing scale and scale of positive and negative experience in Portugal. Social Indicators Research, 110, 469-478. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. L., & Hollinger-Smith, L. (2015). Savoring, resilience, and psychological well-being in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 19, 192-200.. [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F., Hicks, B. M., Kashdan, T. B., Krueger, R. F., & Bouchard Jr, T. J. (2007). Genetic and environmental influences on the positive traits of the values in action classification, and biometric covariance with normal personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 524-539. . [CrossRef]

- Storr, A. (1989). Solitude: A return to the self. Ballantine. https://books.google.co.il/books?hl=iw&lr=&id=FJzUXr5YFD8C&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&ots=t_aL7YBzMd&sig=uBDzTZqFmVwu-DfVt3UA65y9tNQ&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Teppers, E., Klimstra, T. A., Damme, C. V., Luyckx, K., Vanhalst, J., & Goossens, L. (2013). Personality traits, loneliness, and attitudes toward aloneness in adolescence: Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30, 1045–1063. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V., & Azmitia, M. (2019). Motivation matters: Development and validation of the Motivation for Solitude Scale – Short Form (MSS-SF). Journal of Adolescence, 70, 33–42. [CrossRef]

- Urry, H. L., & Gross, J. J. (2010). Emotion regulation in older age. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19, 352–357. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L., Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2020). Character strengths and PERMA: investigating the relationships of character strengths with a multidimensional framework of well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15, 307-328. . [CrossRef]

- Winnicott. D. W. (1958). The capacity to be alone. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 39, 416–420. [CrossRef]

- Ylänne, V., Williams, A., & Wadleigh, P. M. (2009). ageing well? older people’s health and well-being as portrayed in UK magazine advertisements. International Journal of Ageing and Later Life, 4, 33-62. [CrossRef]

| M/% | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 57.20 | 6.24 | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Gender | 71.5% | - | -.02 | 1 | |||||

| 3. Education | 5.26 | 2.03 | .02 | -.02 | 1 | ||||

| 4. Marital Status | 64.7% | - | -.10*** | -.09*** | .01 | 1 | |||

| 5. 24 character-strengths | 3.76 | .40 | .10*** | -.02 | .05 | .02 | 1 | ||

| 5. Flourishing | 5.70 | .90 | .03 | .05 | .10*** | 14*** | .61*** | 1 | |

| 6. The skill of positive Solitude | 3.85 | .74 | -.01 | .08*** | .17*** | -.06 | .31*** | .29*** | 1 |

| Model variables | B | SE | β | F | R2 | R2Δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 9.27*** | .03*** | .03 | |||

| Age Gender |

-.001 .13 |

.004 .06 |

.05 .07* |

|||

| Education | .05 | .01 | .10*** | |||

| Marital Status | .28 | .06 | .14*** | |||

| Step 2 | 123.56*** | .41*** | .37 | |||

| 24 Character-Strengths The skill of PS |

1.32 .12 |

.06 .03 |

.57*** .09*** |

|||

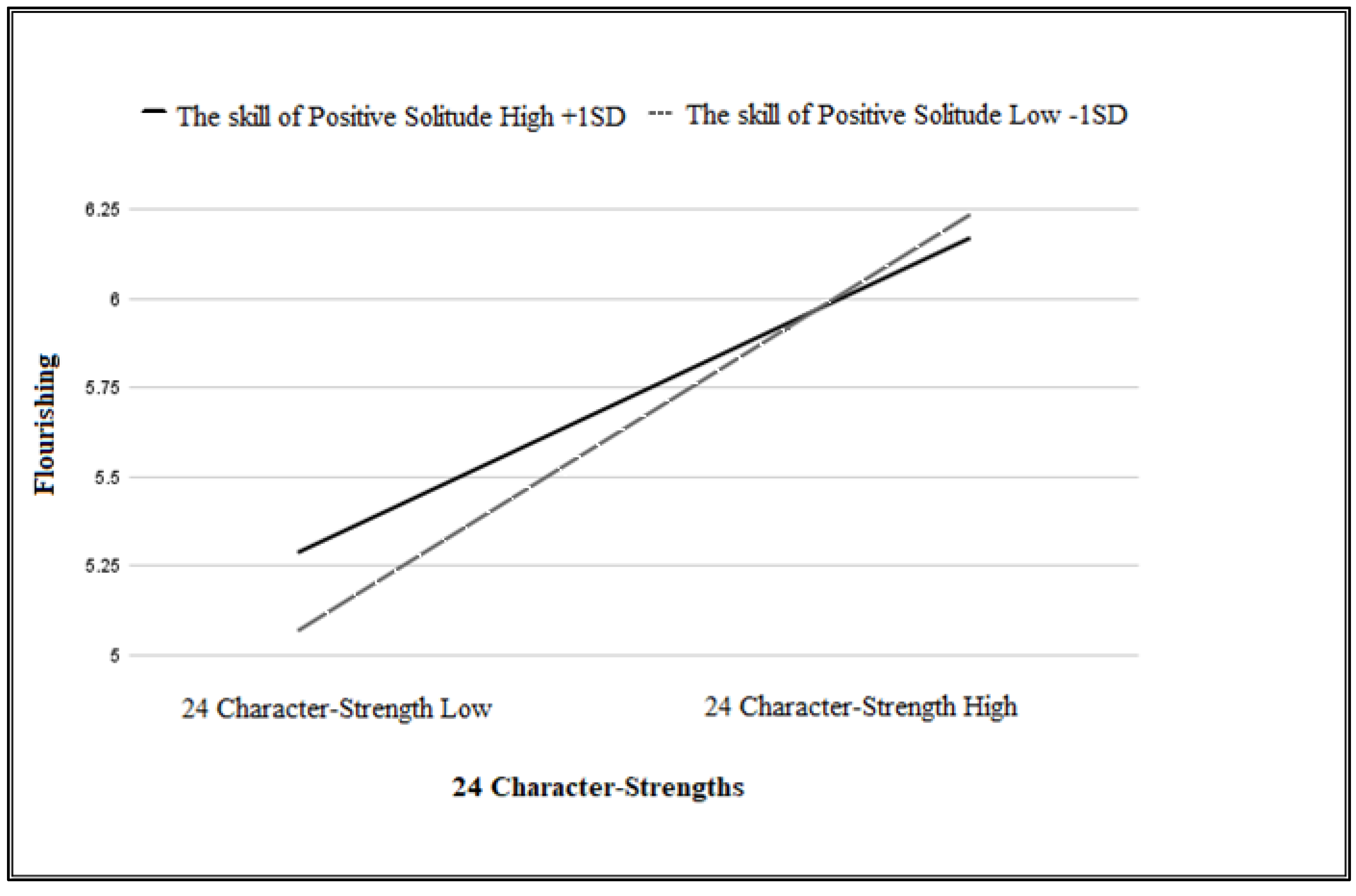

| Step 3 | 110.43*** | .42*** | .01 | |||

| 24 Character-Strengths X The skill of PS | -.26 |

.06 |

-.10*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).