1. Introduction

Family planning (FP) has been identified as one of the essential reproductive health interventions and an essential list of commodities for achieving safe motherhood by reducing maternal and child mortality by limiting the desired number of children and increased spacing between births [

1,

2]. Globally, of nearly two billion women of reproductive age, 1.1 billion need to use FP and of these women, 842 million are users of modern methods of contraception [

3]. Although modern FP usage is rampantly increasing across the world; there are still high unmet needs for modern contraceptives in many developing countries. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the utilization of contraceptive methods is one of the lowest in the world [

4]. It has also been predicted that preventing barriers to the use of contraceptive methods and reaching all women with unmet needs can prevent the 74 million unintended pregnancies, 25 million unsafe abortions, and 47,000 maternal deaths occurring each year in low- and middle-income countries [

5].

Similar to global trends, in Ethiopia, use of contraceptives has been increasing over the past two decades; however, evidence has indicated that 4.5 million women of reproductive age have an unmet need for modern contraception [

6]. According to the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS), there is a high unmet need for contraceptive methods for Ethiopia compared to the target of 10%, which might be due to ongoing conflict, drought, and the effect of COVID -19 [

7]. Besides, there is a large difference in the FP indicators in pastoralist and agrarian regions of Ethiopia. The unmet need for FP is significantly high in pastoralist areas of Ethiopia [

8]. According to the 2016 Mini EDHS report, the prevalence of modern contraceptive methods in the Afar Region, Oromia and Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR) was 12%, 28% and 40%, respectively which is far below that of Addis Ababa (50%) [

9,

10]. Despite the tremendous efforts over the years towards improving FP utilization and reducing the unmet need for FP, still, more than one in five currently married Ethiopian women (22%) still have an unmet need for FP. Oromia, Afar and SNNPR are among the top regions with high unmet needs for FP [

9].

Pastoralist communities are social groups whose way of life is centred around herding livestock, typically in nomadic or seminomadic settings, and relying on domesticated herbivores for sustenance and resources. These communities play significant roles in contributing to their respective regions through driving economic activity, enriching cultural diversity, and promoting environmental sustainability [

11,

12]. These communities depend on raising livestock for their living. By trading livestock and related goods, they boost the local economy [

10]. They cherish unique traditions and practices, which contribute to the diverse culture of the regions. Their ceremonies, rituals, and knowledge about raising livestock are deeply rooted in their heritage [

12].

The pastoralist lifestyle in Ethiopia is deeply rooted in cultural practices and beliefs that have passed through generations, and these beliefs often conflict with modern FP methods. It is therefore timely to dive deep into the current cultural and social norms that affect the use of modern FP methods [

13]. Evidence in other countries also highlights the influence of sociocultural and religious contexts on the utilization of modern contraceptive methods. For instance, in Kenya, fear of side effects or of having a baby with a deformity have been found to be positively associated with not using modern contraceptives [

14]. Similarly, studies in Mali also indicated that many women feared that the pill and injectables could cause permanent infertility [

15].

Various studies conducted in pastoralist areas of other countries have shown that religion, literacy, income status, occupation or employment status, and a desire to have more children are significantly associated with FP utilization and sociocultural practices [

13,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. In the pastoralist context of Ethiopia, there are deeply rooted cultural and social norms that often clash with modern FP practices and limited research has been conducted on FP utilization, with only a few small-scale studies available. Moreover, some existing studies are outdated, lacking current data and insights into contemporary challenges and have been conducted in small pocket areas within pastoralist populations. This highlights the urgent need to explore these sociocultural factors in greater depth. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap by providing detailed insights into the sociocultural factors affecting FP utilization in pastoralist communities by providing up-to-date information that reflects the current sociocultural and economic landscape of pastoralist regions in Ethiopia by incorporating multiple pastoralist contexts in the country. In addition to examining factors directly related to FP use, this study adopts an intersectional lens to explore how intersecting structural factors (e.g., access to healthcare, socioeconomic status) shape FP decisions. This intersectional analysis allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the complex dynamics underlying FP practices in pastoralist contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Setting

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in three regions and six districts to uncover the underlying cultural beliefs and practices related to modern FP utilization and to characterize the current status in the pastoralist community of Ethiopia in January 2024. Ethiopian pastoralist communities are primarily found in the lowland areas of the country, particularly in the regions of Oromia, southern Ethiopia, and Afar. These regions are known for their diverse pastoralist groups and their traditional way of life, centred around livestock herding. In southern Ethiopia (South Omo), pastoralist groups such as Hamer and Dasenech reside in scattered pastoralist settlements along the river valleys and grasslands. Similarly, in Oromia (Borena), pastoralists are found primarily in the Arero districts, while in Afar (Zone 1), communities inhabit areas such as the Afambo and Assayita districts. The pastoralist communities in Borena, Afar, and South Omo in Ethiopia are known for their traditional pastoralist way of life, where they rely on livestock for their livelihoods. The Borena and Afar pastoralist communities are known for their resilient and adaptive survival strategies. However, these pastoralist communities face various challenges, such as land degradation, water scarcity, and conflicts over resources with other communities that threaten their way of life and livelihoods. There have been efforts to support and promote the sustainable development of these communities through various initiatives, although they were not as successful as intended. This study was conducted in pastoralist communities (in three regions: southern Ethiopia (Hammer and Dasench), Oromia (Borena) - Arero district) and Afar (Afambo and Assiyta districts).

2.2. Sample Size and Sampling

A single population proportion formula was used to estimate the sample size, assuming a 95% CI and 5% margin of error, by taking a 50% proportion of FP utilization status assuming an unknown population in the pastoralist community, a design effect of 1.5 and a response rate of 15%. Accordingly, the final calculated sample size was 682 reproductive-aged women. The sample size was proportionally distributed in six randomly selected districts from three regions. These included: i) Southern Ethiopia (South Omo zone: Hammer, Dasench, and Gnagatom; ii) Oromia (Borena) - Moyale, Dhaas and Arero districts; and iii) Afar (zone 1) - (Afambo, Assiyta and Elidar districts). Multistage sampling techniques were employed to select districts, and systematic sampling procedures were employed to reach study participants for whom actual data were collected. The women were identified from the sampling frame, which was generated through the assistance of health extension workers stationed at nearby health posts. A systematic approach was employed to select women from the registered sampling frame.

2.3. Data collection Methods

A pretested structured survey was adapted from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) and previous surveys that were designed to explore factors related to FP utilization barrier studies. A structured survey was administered to women in the community. Quantitative data for the study were collected electrically using Mobil applications, ODK/KOBO, where a structured survey with precoded answers were uploaded. The tools for the data collection were developed in consultation with people who know the culture and language of the study community, and surveys were pretested before actual data collection.

2.4. Data Analysis

Both descriptive and inferential data analysis techniques were employed to analyze the data collected using qualitative and quantitative tools in STATA version 18. While initial bivariate analyses provided insight into the relationship between individual sociodemographic variables and FP utilization, multivariate analysis enabled us to understand the combined influence of multiple factors. By considering interactions among variables, we identified the most influential factors and obtained a more accurate understanding of their impact on FP utilization.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

The survey included a total of 682 women in three regions of Ethiopia, 47% of whom were from southern Ethiopia based on the size of the population. The majority of respondents were illiterate (86%), with only 8% completing primary education. The religious composition was predominantly Muslim (42%), followed by nonbelievers (19%) and traditional belief followers (21%). The mean age of the respondents was 29.1 years. The majority of participants were married or living together (72%), with the majority reporting arranged marriages (89.25% women). Approximately one-fifth of the respondents married before turning 18 years of age. Almost half (47.26%) of the women reported that their husbands had other wives or partners.

3.2. Socioeconomic Characteristics of the Study Participants

The primary sources of income of many of the respondents (80.5%) were primarily subsistence agriculture (56.2% for animal husbandry and 24.3% for smallholder land cultivation). Only less than 5% of the respondents reported paid jobs as their primary source of income. Additionally, less than one-third (32.7%) of the women respondents stated that they were currently working. The average monthly household expenditure of women respondents was reported to be that of Ethiopian Birr (ETB) in 1940.3

1, with the minimum being ETB 120 and the maximum being ETB 8500. However, the average monthly household income was reported to be ETB 2794.7, with the minimum being ETB 200 and the maximum being ETB 35,000.

3.3. Fertility, Unwanted Pregnancy and Contraceptive Practices

The results of the survey regarding fertility and contraceptive practices revealed that the majority of respondents had given birth (70%), with almost two-thirds (61.2%) having a birth spacing of less than two years. Eighty-one percent of the respondents desired their last pregnancy (index pregnancy), indicating a planned pregnancy, while 19.08% did not. The reasons for unwanted pregnancies included more than one-third of the respondents (39%) who mentioned that they did not know how to delay pregnancy at that time and 11% of the respondents who did not know how to access the service at that time, while almost a quarter of the respondents (24%) reported religious prohibition of pregnancy prevention measures. One-fifth of the respondents also mentioned that their husbands had forced them to become pregnant. Almost two-thirds (64%) of women respondents wanted to have more children, while 17% of them did not want to have more children. Fewer than 5% of the respondents reported that they could not determine the number of children to have, and just over a tenth (11%) of them were not sure about it. More than half (57%) of the women respondents wanted to have their next child in less than two years, while 27% of them wanted to give birth between two to four years.

3.4. Contraception Use, Knowledge, and Barriers

The results of the study indicated that contraceptive uptake among women in the intervention areas was relatively low in comparison to that in other regions of the country. Almost half (47.07%) of the respondents had never used contraception in their life, and 52.93% of the respondents reported that they had used contraception before to delay pregnancy. Among those women respondents who used contraceptives, almost half (49.63%) were currently using a contraceptive method, while half (50.37%) of the total women respondents were not currently using any FP methods. The most commonly used contraceptive methods in the study areas were found to be injectables (54.14%), followed by implants (51.78%), pills (34.62%), IUDs (14%), condoms (2%) and other methods (2.9%). The percentage of respondents with contraceptive knowledge (at least one method) in this study was 98%, which is similar to the national figure (>99%). In terms of knowledge of contraception methods, injectables and implants were the most commonly known methods, followed by pills, and male condoms. This study indicated that approximately 62.61% of respondents reported that they used to visit health facilities for family planning-related services, while almost two-fifths of the respondents (37.39%) did not.

3.5. Reasons for Not Using and Discontinuation of FP Services

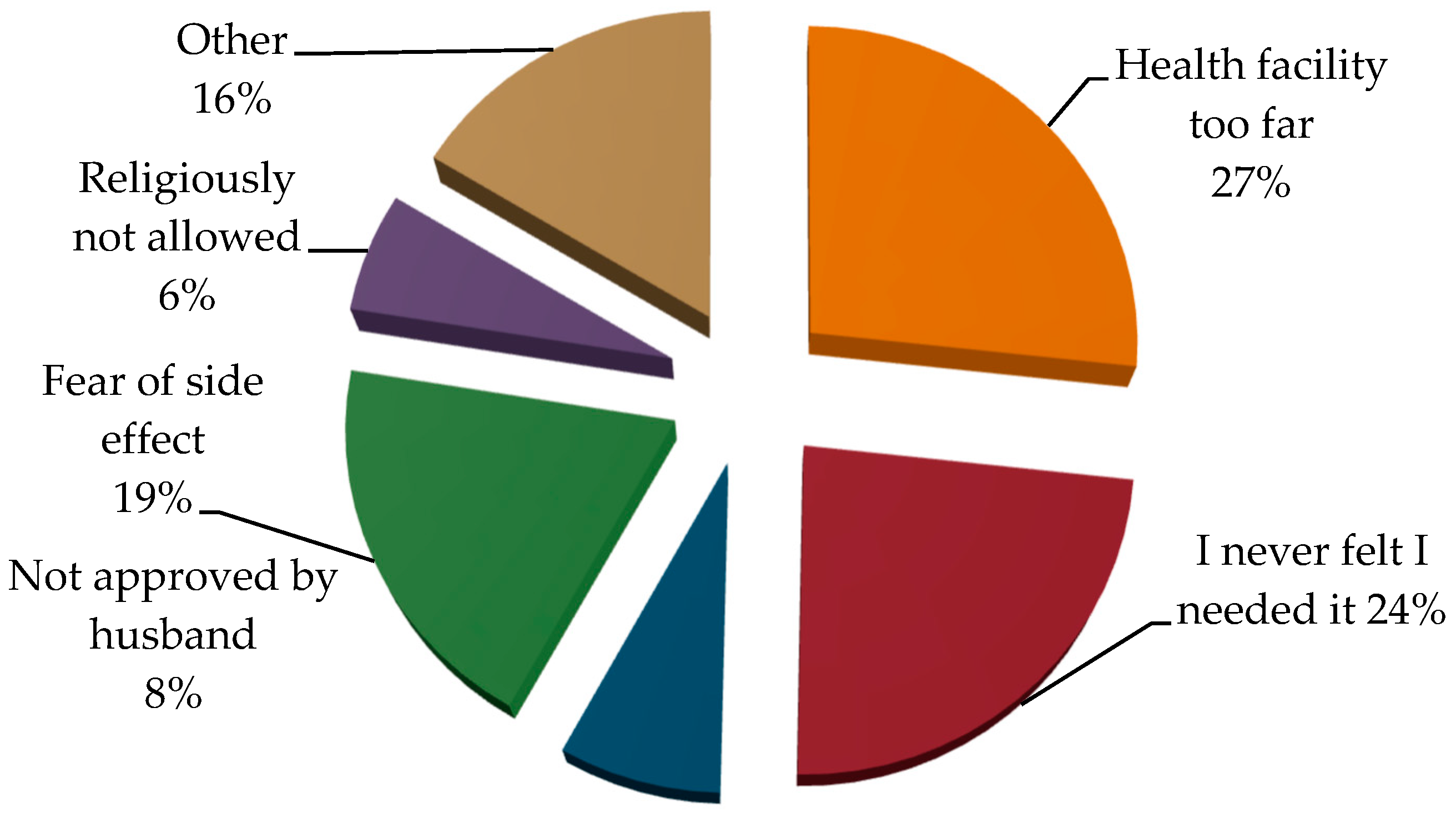

Reasons for not using modern contraceptive methods varied among respondents, with fear of side effects (38%), fear of infertility (27%), reasons related to religious prohibition (20%) and the desire to become pregnant (14%) being prevalent concerns. Other reasons included disapproval of husbands, lack of information related to the nature of the contraceptive, not liking modern methods and miscellaneous factors. The findings of this study showed that the discontinuation of contraceptive use was influenced by various factors. Among the respondents, 26.7% reported that the primary reason for discontinuing contraceptive use was travelling long distances to health facilities, which made it challenging to access necessary services and supplies. Additionally, 23.65% of the respondents mentioned that they had never felt the need to continue using contraceptives, possibly due to changes in their reproductive plans or a lack of awareness about the importance of consistent contraceptive use. This study also revealed that 7.73% of respondents cited disapproval from their husbands or mothers-in-law as a major reason for discontinuation of contraceptives. Fear of side effects was mentioned by 19.44% of respondents, suggesting concerns about the potential negative impacts of using contraceptives. Furthermore, 6.09% mentioned that religious beliefs did not allow continued contraceptive use (

Figure 1).

3.6. Attitudes towards FP and Reproductive Rights of Women

The results of this study regarding the perspectives of individuals about pregnancy and its impact on families revealed that more than half (54%) of women highlighted the positive impact of pregnancy prevention on the economic stability of families, and 22% of women recognized the health benefits of preventing pregnancy. Forty-four percent of women completely agreed that they should suggest contraceptive use with their husbands, 25.8% of women slightly agreed that it is acceptable for wives to suggest contraceptive use to their husbands, and less than half (46%) indicated that their husbands do not support the use of modern contraceptive methods. When asked about the agreement of wives with a husband suggesting contraceptive use, a significant percentage (43%) completely and slightly agreed (28%) that it is normal, while a relatively lower percentage of the respondents (17%) disagreed on the issue. This suggests that pastoralist women should be supported by their husbands or partners in family planning-related issues. Similarly, almost two-thirds (65.5%) of the respondents indicated that the community disrespected them if unmarried women used FP services. Similarly, more than two-thirds of the respondents (68%) mentioned that unmarried women ceased using FP methods because of fear of disrespect from the community.

More than two-thirds (69%) of husbands agreed that they expected their wives not to use FP services so that they could have large families. In particular, almost three-quarters (71.5%) of women respondents reported that they were expected not to use FP services so that they could have large families. Only less than a fifth (19%) of the respondents disagreed with this expectation (see

Table 2 below).

The results of the survey regarding women’s decision power indicated that they have limited decision power even to exercise their sexual reproductive health and rights. The survey revealed that if married women use FP methods without the consent of their husbands, more than two-thirds (70%) of the respondents believed that conflicts would arise, potentially leading to divorce. Only approximately 18% of the respondents disagreed with this viewpoint, and 11% responded that they were unsure about the consequences. In relation to this, more than two-thirds (68%) of respondents mentioned that married women usually stop using FP due to fear of conflict with their husbands.

Consistent with this, almost two-thirds (61%) of the respondents believed that a man should never allow his wife to decide on the size of the family. Similarly, more than two-thirds (68%) of the respondents reported that it was mainly women’s responsibility to ensure that contraception was used regularly, and more than two-thirds (70%) of the respondents were women.

Almost half (43%) of the respondents reported not having engaged in open discussions about FP with their partners.

The results of this study also highlighted that more than half (58%) of the respondents agreed that a girl should never get married before 18 years of age, although one-fifth of the respondents still believed that a girl should get married when the father/husband decided irrespective of her age. Likewise, 58% of the respondents believed that a girl should never give birth before 18 years of age, while one-fifth of the respondents believed that a girl could give birth anytime she thought it best for her. Almost one-third (28.9%) of the respondents also believed that unmarried women under the age of 18 should not be allowed to use FP services, while 58.74% agreed that they should be allowed to use FP services. In terms of birth spacing, more than half of respondents (52.6%) preferred a gap of less than two years between births, 27% preferred a gap of two to three years, and a smaller percentage (11%) had other preferences. A small proportion of the respondents (9.24%) were undecided or did not know about their preference for birth spacing.

3.7. Women’s Decision-Making Skills

The results on gender roles and decision-making within a household revealed that more than two-thirds (70.33%) of respondents agreed that it was mainly the women’s responsibility to ensure that contraception is used regularly, although almost a quarter (22.03%) of the respondents disagreed (see

Table 3). Almost two-thirds (60.5%) of the respondents agreed that a man should never allow his wife to decide on the number of children to have. Likewise, almost one-third (31.23%) of the respondents believed that the husband should take the upper hand in making decisions on large household purchases, while 54.55% believed that it should be a joint decision made by both the wife and husband.

In terms of healthcare decisions for women, almost three-quarters (71.7%) of respondents believed that it should be a joint decision made by both the wife and husband. A smaller percentage (17.3%) thought the husband should make this decision, while only 1.32% believed the wife should make this decision. Similarly, almost three-quarters (71.11%) of respondents believed it should be a joint decision made by both the wife and husband on the use of contraceptives. Again, a smaller percentage (17.3%) thought the husband should make this decision, while 3.81% believed the wife should make this decision.

3.8. Multivariable Binary Logistic Regression

Hierarchical logistic regression was fitted to sequentially add groups of variables to the model without using FP as the dependent variable. Predictor variables were grouped based on their conceptual similarities, such as sociodemographic situation, socioeconomic situation, access to and use of FP, knowledge, attitudes and perceptions and, finally, sexuality and gender norms. The final model was selected because of its better fit for the data. The likelihood ratio chi-square test statistic was 263.06, with a p value of 0.0000, indicating that the model significantly predicted the outcome variable. Moreover, the pseudo-R-squared value was 0.4382, suggesting that the model explained approximately 44% of the variance in the outcome.

The analysis revealed that the odds of not using FP were approximately threefold greater for individuals with birth spacing less than two years than for those with longer birth spacing. This odds ratio is statistically significant, with a p value of 0.002, suggesting that the relationship between birth spacing and not using FP was unlikely to be due to random chance. In addition, the odds of not using FP was approximately 7.7 times greater for individuals who did not plan their last pregnancy than for those who did want a pregnancy for the index child. It is also significant, with a p value of 0.000, indicating that the relationship between not wanting the pregnancy for the index child and not using FP is unlikely to be due to random chance.

Moreover, compared to women who had their husbands’ support when taking contraception, women whose husbands did not support were approximately 16 times more likely to not use FP (AOR =15.88), with a p value of 0.000, this odds ratio is statistically significant and suggests that there is more reason than chance for the association between not using FP and a husband’s lack of support. Thus, the logistic regression analysis showed that women who did not receive spousal support for contraceptive use were far more likely to not use FP than were those who did. The likelihood of not using FP was approximately two times greater for women who did not think that it was mainly the woman’s responsibility to ensure contraception use than for those who thought it was the woman’s responsibility. This odds ratio (AOR=2.00) is statistically significant with a p-value of 0.047, suggesting that the relationship between this belief and not using FP is unlikely to be due to random chance.

The results of the multiple logistic regression analysis also revealed a significant association between the husband’s decision-making authority for large household purchases and the likelihood of not using FP methods. Specifically, the odds ratio of 0.176, with a p-value of 0.000, indicated that when a woman does not have decision-making authority on large household purchases or if only a husband or someone else decides on these purchases, the odds of not using FP methods increased by approximately 82.43%, in comparison to when she was involved, holding all other variables constant. Similarly, the analysis also indicated a statistically significant association between lower decision-making authority for her own health care services and the likelihood of not using FP methods. The odds ratio of 3.54, with a p-value of 0.005, suggested that when a woman has no decision-making authority or when the decision-maker is limited to a husband or someone else, the odds of not using FP methods increased by approximately three times compared to when the woman has decision-making authority for health care services. This emphasizes the need to consider the role of decision-making authority as a crucial factor in influencing FP behavior. These findings provide valuable insights for further research and initiatives focused on understanding the complex interplay between household dynamics and FP practices.

The amount of household expenditure is one of the significant predictor variables, with an odds ratio of 0.90 and a p value of 0.018. Despite the odds ratio being close to 1, indicating a minimal effect, the statistically significant p value provides evidence that lower levels of expenditure does have a discernible impact on the likelihood of not using FP methods.

4. Discussion

Our study assessed the sociocultural impact on women’s utilization of modern contraceptives in pastoralist areas of Ethiopia. The results of our study revealed that 47% of the overall population did not use FP, with regional variations reported. The findings of our study are lower than those of the 2016 Mini EDHS 2019, which reported that overall, 88% of Afar, 72% of Oromia and 60% of the SNNPR did not use FP [

9]. This variation might be due to changes in sociocultural factors, improved accessibility of healthcare services, increased availability and awareness of contraceptive methods, and evolving patterns of reproductive health behaviours over time that might increase the use of FP.

The findings of our study showed that there was a statistically significant association between decreased birth spacing, lower expenditure, and low decision making in women who did not use FP methods. Women who reported that they had shorter (less than one year) birth spacing were three times more likely not to use FP than were those who had birth spacing between two or more years. This finding is supported by a systematic review and meta-analysis [

21]. Our study showed that women who had never used contraception before the conception of their last child were 3.87 times more likely to have short birth spacing than women who utilized contraceptive methods. This can be explained by living in pastoralist communities and cultural or religious beliefs that prioritize fertility or discourage modern contraceptive use. Additionally, a strong preference for larger family sizes and societal norms encouraging frequent childbearing can contribute to shorter birth intervals, as women may not actively seek to delay or space pregnancies. This might also be related to lower awareness about FP, religion, and limited access to family services [

21,

22]. Moreover, the potential for the perception of affordability might also contribute to these areas; although the services provided in Ethiopia are free, the indirect cost of transport can contribute to limited access [

23].

Our study revealed that lower household expenditures were associated with not using FP. Our study showed that an increase in monthly income was associated with the likelihood of using FP methods. Mothers who had higher monthly incomes had greater odds of using FP than mothers with the lowest incomes. This might be due to limited household expenditure impacting access to healthcare facilities and services. Families with lower expenditures may face barriers such as transportation costs, healthcare fees, or a lack of nearby facilities offering FP services, further hindering the use of FP.

Moreover, women whose husbands or someone else (other than themselves) made decisions about large household materials (82%) were significantly less likely to use FP than women who make these decisions themselves or jointly with their husbands. On the other hand, when decisions about women’s healthcare were made solely by their husbands or someone else, women were 3.4 times less likely to use FP in comparison with decisions made by the women themselves or jointly. The findings of our study are supported by a community based cross sectional study conducted in a pastoralist community of Ethiopia [

17]. Our study revealed that women’s increased decision making about FP is significantly associated with increased FP use. In pastoralist community contexts, women’s decision-making autonomy reflects broader shifts in gender norms and power dynamics within households and communities. Increased involvement in decision-making can signify progress towards gender equality and women’s empowerment [

23].

In our study, women who disagreed with the idea that it is mainly women’s responsibility to ensure that contraception is used regularly were found to be twice as likely not to use FP in comparison to women who agreed with this responsibility. This may be because women who believe that contraception is primarily their responsibility are also more likely to take ownership of FP decisions and actions. When women do not see contraception as their responsibility, they may be less proactive in seeking and using FP services [

24].

Women whose husbands do not support the use of modern contraceptives are 16 times more likely to not use FP than women whose husbands who support modern contraceptive use. To explain this, the absence of spousal support for modern contraception significantly influences women’s decision-making regarding FP practices. This finding is supported by a community-based cross-sectional study conducted in the Bale Zone [

16]. Our study showed that the odds of modern contraceptive utilization among women whose husbands supported the use of modern contraceptives were eight times greater than those among women whose husbands did not support the use of modern contraceptives. In pastoralist societies, husbands often hold significant decision-making power within relationships. Cultural or religious beliefs that prioritize large families or oppose contraceptive use can influence husbands’ attitudes towards FP. If husbands oppose modern contraceptive use, women may face difficulties using FP methods. Women may conform to their husbands’ beliefs or preferences due to societal norms or religious teachings, impacting their decision-making on using contraceptives [

25].

Women who experienced unwanted pregnancies were 7.2 times more likely not to use FP than women who wanted or planned a pregnancy. Our study is supported by a study in Jimma, which revealed that unintended pregnancy was strongly associated with not using contraceptives [

26]. This suggests a gap in contraceptive access, knowledge, or utilization.

5. Conclusions and Recommendation

Overall, our study highlights the complex interaction between sociocultural, economic, and gender dynamics that influence FP practices in pastoralist communities of Ethiopia. The proportion of women not using FP was significantly high, which is an indication of the high unmet needs of women’s reproductive health. Most importantly, our study revealed that a lack of partner support significantly contributed to not using FP methods among women. Additionally, the study revealed that women who do not have high decision-making authority on large household purchases or healthcare services are also more likely not to use FP methods, underscoring the importance of women’s empowerment and autonomy in reproductive health decisions. Moreover, our study revealed that lower household expenditures are associated with not using FP, indicating that financial barriers, such as transportation costs and healthcare fees, can hinder access to FP services. Furthermore, our study also emphasizes the meaningful connection between limited birth spacing and not using FP services, suggesting that cultural or religious beliefs that prioritize fertility or discourage modern contraceptive use may contribute to shorter birth intervals.

Based on the findings, the following recommendations are proposed for policy and program implementation: I) Implement targeted educational campaigns to raise awareness about the importance of FP, birth spacing, and contraceptive methods. These programs should focus on dispelling myths, addressing cultural beliefs, and promoting the benefits of FP for women’s health and well-being; II) Encouraging women’s involvement in decision-making processes that can enhance their autonomy and lead to increased uptake of FP methods; III) Establishing programs that engage men and promote their support for FP and contraceptive use and the benefits of FP. Addressing misconceptions, and involving them in FP decisions can positively impact women’s access to utilization of contraceptive methods; and IV) Providing financial assistance or incentives to households with lower expenditures to improve access to healthcare services, including FP. Addressing financial barriers such as transportation costs and healthcare fees can increase the utilization of FP methods among economically disadvantaged populations. V) Engaging community leaders, religious figures, and local influencers can help challenge societal norms, reduce stigma about FP, and encourage positive attitudes toward contraceptive use.

By implementing these policies based on the research findings, Ethiopia can work toward improving FP practices, empowering women, and enhancing reproductive health outcomes in pastoralist communities.

Author Contributions

M.D.M, M.B, V.S., W.K., A.R, S.A, M.H, and G.A were involved in the conceptualization of this study. M.D.M., W.K; M.B carried out the analysis and drafted the manuscript. All others were involved in the revision and editing of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research was funded by the European Union, as part of the “RESET Plus - Scaling up the Family Planning for Resilience Building program amongst youth and women in drought prone and chronically food insecure regions of Ethiopia (T05-EUTF-HOA-ET-24-08)””.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board (IRB) of the Ethiopian Public Health Association, Ref N ETCO/268/2. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board Debre Berhan University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed verbal consent was obtained from the respondents. Confidentiality and privacy were maintained during data collection, analysis and reporting.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available based on request from corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the European Union, as part of the “RESET Plus - Scaling up the Family Planning for Resilience Building program amongst youth and women in drought prone and chronically food insecure regions of Ethiopia (T05-EUTF-HOA-ET-24-08)” project and conducted by Amref Health Africa. The researchers are thankful toward both the European Union for funding the project and Amref Health Africa for providing access to data and administrative support

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- Mwaikambo L, Speizer IS, Schurmann A, Morgan G, Fikree F. What works in family planning interventions: a systematic review. Stud Fam Plann. 2011;42(2):67-82. [CrossRef]

- (WHO) WHO. Ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services: Guidance and recommendations.. 2019.

- UN. Family Planning and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2019.

- Cleland J, Bernstein S, Ezeh A, Faundes A, Glasier A, Innis J. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. Lancet. 2006;368(9549):1810-27. [CrossRef]

- Jacobstein R, Bakamjian L, Pile JM, Wickstrom J. Fragile, threatened, and still urgently needed: family planning programs in sub-Saharan Africa. Stud Fam Plann. 2009;40(2):147-54.

- Institute, G. ADDING IT UP: Investing in Contraception and Maternal and Newborn Health In Ethiopia. April,2019.

- UN News GpHs. Conflict, drought, dwindling food support, threatens lives of 20 million in Ethiopia | UN News. 2022.

- EngenderHealth. Understanding Barriers to Family Planning Service Integration in Agrarian and Pastoralist Areas of Ethiopia through a Gender, Youth, and Social Inclusion Analysis 2022.

- Agency, CS. Ethipia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2016.

- Institute EPH. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019. Report. 2019.

- Headey D, Taffesse A, You L. Diversification and Development in Pastoralist Ethiopia. World Development. 2014;56:200–13. [CrossRef]

- Agriculture dorea. Policy framework for pastoralism in africa securing, protecting and improving the lives, livelihoods and rights of pastoralist communities. 2013.

- Alemayehu M, Lemma H, Abrha K, Adama Y, Fisseha G, Yebyo H, et al. Family planning use and associated factors among pastoralist community of afar region, eastern Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. 2016;16:39. [CrossRef]

- Rutenberg N, Watkins SC. The buzz outside the clinics: conversations and contraception in Nyanza Province, Kenya. Stud Fam Plann. 1997;28(4):290-307. [CrossRef]

- Castle, S. Factors influencing young Malians’ reluctance to use hormonal contraceptives. Stud Fam Plann. 2003;34(3):186-99. [CrossRef]

- Belda SS, Haile MT, Melku AT, Tololu AK. Modern contraceptive utilization and associated factors among married pastoralist women in Bale eco-region, Bale Zone, South East Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):194. [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu M, Medhanyie AA, Reed E, Mulugeta A. Individual-level and community-level factors associated with the family planning use among pastoralist community of Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e036519. [CrossRef]

- Damtie Y, Kefale B, Yalew M, Arefaynie M, Adane B. Short birth spacing and its association with maternal educational status, contraceptive use, and duration of breastfeeding in Ethiopia. A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246348. [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu M, Medhanyie AA, Reed E, Kahsay ZH, Kalayu M, Mulugeta A. Effects of continuum of care for maternal health service utilisation on intention to use family planning among pastoralist women of Ethiopia: a robust regression analysis and propensity score matching modelling. BMJ Open. 2023;13(7):e072179. [CrossRef]

- Mesfin Yesgat Y, Gebremeskel F, Estifanous W, Gizachew Y, Jemal S, Atnafu N, et al. Utilization of Family Planning Methods and Associated Factors Among Reproductive-Age Women with Disability in Arba Minch Town, Southern Ethiopia. Open Access J Contracept. 2020;11:25-32.

- Moreira LR, Ewerling F, Barros AJD, Silveira MF. Reasons for nonuse of contraceptive methods by women with demand for contraception not satisfied: an assessment of low and middle-income countries using demographic and health surveys. Reproductive Health. 2019;16(1):148. [CrossRef]

- Kenny L, Lokot M, Bhatia A, Hassan R, Pyror S, Dagadu NA, et al. Gender norms and family planning amongst pastoralists in Kenya: a qualitative study in Wajir and Mandera. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2022;30(1):2135736.

- Jisso M, Assefa NA, Alemayehu A, Gadisa A, Fikre R, Umer A, et al. Barriers to Family Planning Service Utilization in Ethiopia: A Qualitative Study. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2023;33(Spec Iss 2):143-54.

- Ewerling F, Lynch JW, Victora CG, van Eerdewijk A, Tyszler M, Barros AJ. The SWPER index for women’s empowerment in Africa: development and validation of an index based on survey data. The Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(9):e916-e23.

- Kenny L, Bhatia A, Lokot M, Hassan R, Hussein Aden A, Muriuki A, et al. Improving provision of family planning among pastoralists in Kenya: Perspectives from health care providers, community and religious leaders. Global Public Health. 2022;17(8):1594-610.

- Dibaba, Y. Child spacing and fertility planning behavior among women in mana district, jimma zone, South west ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2010;20(2):83-90.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).