1. Introduction

Thailand recognizes healthcare decentralization as a key strategy for enhancing the quality, efficiency, and equity of its health systems. This was facilitated by the 1997 Constitution [

1,

2,

3], which empowered local authorities and citizens to manage their health services. Subsequent legislation in 1999 and decentralization plans in 2000 and 2008 further outlined the processes for local governance to improve public health and disease management [

1,

2,

3]. This restructuring extends to various local administrative bodies, underscoring the role of decentralization in supporting effective health insurance and overall healthcare provision at the local level [

4].

According to the Thai Constitution of 2017 [

4], the decentralization of public health responsibilities aims to empower local governance to manage and provide health services in accordance with legal stipulations. This includes the planned transfer of responsibilities to local governing bodies for public health services and activities, as well as defining processes for transferring responsibilities, budgets, and personnel [

4]. National reform policies, which include guidelines and processes for the transfer and appointment of committees to manage transferred duties, support this shift. Assessments from 2008 to 2020 [

4], however, indicated delays in the transfer process, with only 70 of the planned 60 health-promoting hospitals transferred from a total of 9,787 nationwide [

4]. The appointment of committees to oversee these transfers has also not met planned targets, necessitating a review and improvement of the transfer processes to ensure efficient and effective public health operations according to reform policies [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Primary care services are critical for national public health development, emphasizing continuous quality access to healthcare. International data analysis shows that robust primary healthcare systems enable efficient access to essential health services. Local health committees have designated health-promoting hospitals for management and integration within the health system, with the aim of enhancing service quality and benefiting the local population [

5,

6].

The development of primary healthcare systems is critical for ensuring equitable access to health services and reducing hospital congestion in Thailand [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. In 2023 [

11], they issued a new health service standard to foster development and evaluate service quality equitably and efficiently. However, issues related to social and cultural standards persist, where healthcare personnel behavior plays a significant role. Therefore, it is important to focus on developing primary healthcare personnel, such as through training and skill development in clinical nursing, to enhance patient care, health promotion, and disease prevention [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Moreover, service integration and human resource management in primary care units need improvement [

18,

19]. Problems such as lack of staff motivation, inadequate medical supplies, unlinked referral systems, and insufficient funding have emerged following the transfer of health-promoting hospitals to local government organizations, resulting in decreased service quality [

20]. Thus, this study recognizes the need to investigate factors affecting service provision and propose policies emphasizing the role and potential of nurses in delivering comprehensive services across all age groups, thereby enhancing quality, and integrating the service system more effectively and to higher standards.

1.1. Research Purpose

The aim of this study is to investigate factors that affect healthcare delivery in sub-district hospitals transferred to provincial administrative organizations.

1.2. Conceptual Framework

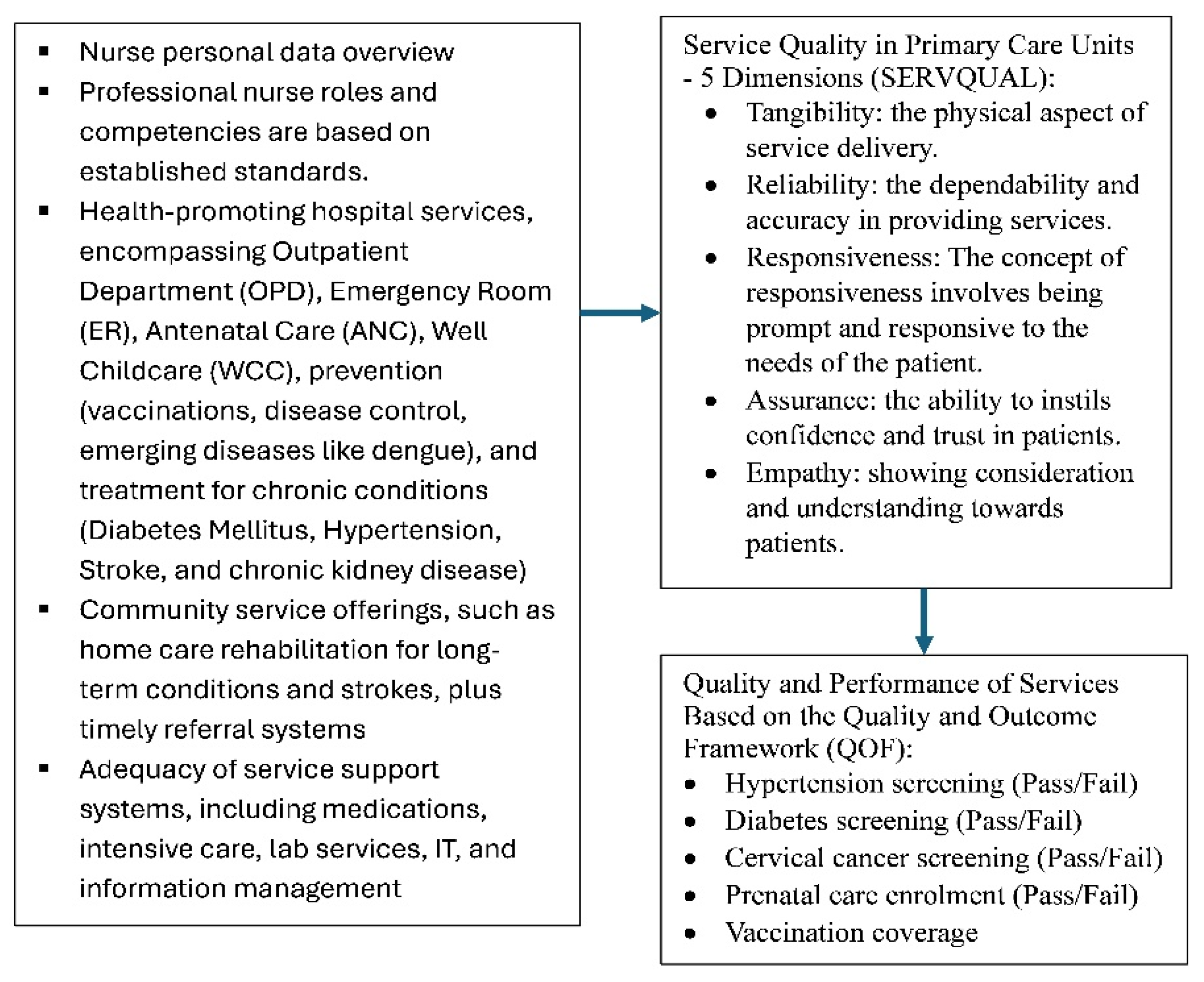

The study employs the Global Fund-HSS framework [

19] and divides into four major sections: Input factors consist of six building blocks focusing on service delivery and the workforce: Processes based on nursing skills include treatment, promotion, prevention, and rehabilitation. Outputs encompass services in healthcare facilities and communities; SERVQUAL and the QOF guide the measurement of outcomes through service effectiveness and quality (

Figure 1).

2. Materials and Methods

This mixed-methods study was conducted from October to December 2023. The research project was presented and approved by the Ethics Committee for Research in Human Subjects at Hua Hin Hospital, project number RECHHHNo.011/2023. The study was carried out according to the established procedures. Researchers explained the objectives, expected benefits, methods, and procedures that participants were required to follow, ensuring the confidentiality of the collected data, which was anonymized to be used solely for research purposes. Participants had the right to refuse or withdraw from the study without any consequences. Consent was obtained from all participants who signed the informed consent form before participating in the study.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

2.1. Population and Sample

The sample consisted of 342 professional nurses, calculated using Daniel and Cros

s’s formula [

12], resulting in a sample size of approximately 341persons.

Professional nurses working in health-promoting hospitals post-transfer for at least six months were the inclusion criteria. Discontinuation criteria included discomfort or distress related to research questions, as well as immediate termination of data collection and destruction of personal documents if volunteers expressed a desire to withdraw. Additionally, volunteers reported coercion from superiors to participate; the researcher would terminate the data collection and destroy personal documents immediately.

2.2. Research Instruments

The study used a questionnaire with seven sections with eight items; Part 1 includes general personal information about nurses. Part 2 covers the health-promoting hospital’s general information and activities. Part 3 concerns the service provider team. Part 4 focuses on core indicators (Quality and Outcome Framework: QOF) and primary service outcomes, which include: Percentage of Thai population aged 35–74 screened for diabetes by blood sugar level. We screened a portion of the Thai population aged 35–74 for high blood pressure. The study aims to determine the percentage of pregnant women who receive their first antenatal care within 12 weeks. Percentage of women aged 30–60 screened for cervical cancer within a five-year period. Part 5 is a questionnaire with 39 questions about the roles, duties, and skills of professional nurses in hospitals that promote health. The questions are based on the Canadian Nurses Association’s studies [

13] on the roles, duties, skills, and scope of practice of professional nurses, as well as other relevant studies [

13]. Part 6 rates the quality of service in primary care units based on how people actually feel and what they expect. It does this by using a questionnaire created by Kittisak Saengthong [

15] that uses the five dimensions of SERVQUAL: tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy. Each dimension has five questions, and the answers are given on a five-point Likert scale [

17]. Part 7 contains 11 items about leadership qualities necessary for administrators in health-promoting hospitals, scored on a five-point Likert scale, calculating average scores per Best’s formula [

14].

2.3. Quality Verification of Research Instruments

Three qualified experts assessed the content validity of the research instruments, leading to revisions based on their recommendations. This included calculating the Index of Item Objective Congruence (IOC) for seven parts of the nursing research questionnaire, yielding indices of 0.99, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, and 1.00, respectively.

2.4. Data Collection

Preparation Stage: The researcher, a crucial tool in data collection and analysis, has extensive experience conducting and publishing both domestic and international qualitative research. Initial steps involved establishing contact and inviting participants, clearly explaining the research objectives and scope. Implementation Stage: The researcher-built rapport with participants by introducing themselves and explaining the purpose and details of the questionnaire. The researcher scheduled appointments for data collection, specifying the place, date, and time. Data Collection: The researcher collected data in private settings. The researcher minimized bias and maintained consistent conduct to underline the importance of the data collected, ensuring no significant data was overlooked.

2.5. Data Analysis

Descriptive Statistics: To summarize the data, we analyzed the personal data of the sample group using descriptive statistics. Paired t-test: We used this statistical test to compare the effectiveness before and after the intervention. One-Way ANOVA: We used this method to compare the effectiveness between groups. Binary Logistic Regression Analysis: We used this analysis to test factors affecting the quality-of-service provision.

We conducted the qualitative data analysis using Streubert-Speziale & Carpente

r’s [

21] content analysis guidelines. The process included: (1) Understanding the data: The researcher read and reviewed each line of the transcribed interview data to grasp an overall understanding of the participant

s’ thoughts, feelings, and experiences, keeping the research objectives in mind. (2) Meaning Units: We identified words, sentences, or paragraphs as important meanings reflecting the participant

s’ experiences related to primary care service quality [

21]. We then condensed these into condensed meaning units, coded them, and organized them into related sub-themes and broader themes. (3) Linking Themes: The final step was to connect the sub-themes to form comprehensive themes that reflect the quality of primary care services.

2.6. Ensuring Trustworthiness

Lincoln & Guba [

21] established the dat

a’s trustworthiness via: (1) Credibility: Expert reviews and participant confirmation of the findings ensured data coverage, depth, and saturation. (2) Dependability: The researcher independently analyzed reflection notes and group discussion transcripts, then discussed the findings with co-researchers and experts in community and qualitative research. (3) Transferability: We selected a diverse sample group based on age, gender, and study area to provide data that readers can apply to similar contexts, and (4) Confirmability: Throughout the study, we conducted data triangulation using various documents such as audio recordings, field notes, and personal reflection journals in NVivo 10 [

22], to ensure consistent reference and verification of the data.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Services at Sub-District Health-Promoting Hospitals under Provincial Administrative Organizations

As mandated by the Primary Health System Act of 2019, the majority of medium-sized hospitals in Health Area 7 were categorized as PCUs (Primary Care Units), with 59.82% recognized as PCUs and 32.54% as NPCUs (Non-Primary Care Units) before being transferred to the Provincial Administrative Organization. Initially, these hospitals enjoyed a high star rating of 98.83%; however, this rating declined to 83.63% subsequent to the transfer. On average, these hospitals cater to 5,104.05 individuals (SD = 3,504.05), predominantly serving areas with 3,000 to 8,000 people (60.69%) and managing no more than 1,000 households (63.11%). The coverage extends to health insurance (54.60%), civil servant benefits (69.84%), and social security (54.81%), with responsibilities spanning 6-10 villages (47.48%). Research indicates variability in the roles and competencies of professional nurses’ post-transfer. The highest recorded competency was in health promotion, with an average score of 4.15 (SD = 0.66). In contrast, the competency in developing primary nursing quality was the lowest, averaging 3.76 (SD = 0.81). Specific tasks such as patient history-taking and assessment showed consistency, each scoring 4.41 (SD = 0.62 and SD = 0.66, respectively). Acknowledging these disparities is crucial for devising effective methods to advance and refine community health services.

3.2. Study Objective: Factors Affecting Service Provision in Sub-District Health-Promoting Hospitals Transferred to Provincial Administrative Organizations

The analysis focused on service quality in primary care units. (1) The analysis measured service provision across six aspects: medical treatment, health promotion, disease prevention and control, rehabilitation, emergency care, and palliative care management. Post-transfer, the highest average scores were notably within the group that transferred entirely, especially in tangible aspects of service at a mean of 3.92, reliability at 4.28, responsiveness at 4.19, assurance at 4.40, and empathy at 4.61. (2) Expectation vs. Reality Post-Transfer: When comparing expectations to actual perceptions of service post-transfer, the expectation scores were consistently higher than the actual perception scores across all aspects, showing statistically significant differences at the 0.05 level. This discrepancy was particularly pronounced in the group with 100% transfer, highlighting significant statistical differences across all aspects at the 0.05 level. In contrast, groups with less than 50% transfer exhibited higher expectation scores than perception scores, with significant differences only in the dimensions of equitable and discrimination-free service provision, and no significant statistical differences in attentive and respectful treatment. (3) Staff Attitudes Before and After Transfer: Before the transfer in the fiscal year 2025, the overall average attitude score of the service team was 3.60 (SD = 0.88), with the highest average concerning patient and public benefit at 4.21 (SD = 0.67). Post-transfer in 2026, the overall average improved slightly to 3.72 (SD=0.93), maintaining the highest scores for patient and public benefit at 4.21 (SD=0.77) and improved relations with colleagues at 4.04 (SD=0.73). The aspect with the lowest average both before and after the transfer was compensation perceived as adequate, scoring 3.01 (SD=0.84) initially and slightly increasing to 3.04 (SD=1.01) after the transfer.

Outcome comparison across primary healthcare units’ indicators before and after a complete transfer indicated a significant reduction, particularly in indicators affecting the overall population, as evidenced by statistical significance at the p-value of 0.05. In the cohort transferred between 50% and 99%, various indicators exhibited declines from baseline, although some, like cervical cancer screenings for women aged 30-60 within five years, did not meet the statistical significance threshold. Notably, in units transferred less than 50%, significant variations were observed in health screenings such as diabetes and hypertension among the Thai population aged 35-74, underscoring the profound effects of service transfer on local health maintenance and development. These insights emphasize the need for strategic implementation to enhance future health outcomes, detailed further in

Table 1.

We employed ANOVA statistics in an analysis, stratified by the extent of transfer—100% in Group 1, 50–99% in Group 2, and less than 50% in Group 3—to assess outcome differences across primary healthcare units. The analysis included key health indicators: diabetes screening among Thais aged 35–74, initial antenatal visits within 12 weeks for pregnant women, and cervical cancer screenings within five years for women aged 30–60. The findings revealed statistically significant variations in at least one of these groups, demonstrating differences in healthcare delivery effectiveness across the different levels of transfer that were significant at a p-value of 0.05 in

Table 2.

4. Discussion

The operational process of the study examining factors influencing service provision in sub-district health-promoting hospitals transferred to provincial administrative organizations can be divided into three systems: Input, Process, Output, and Outcomes, focusing on service outcomes and quality according to SERVQUAL and QOF. The discussion can be divided into three areas: 1) System Development, 2) Nursing Practices, and 3) Quality of Care, as follows:

4.1. System Development

The study revealed that in terms of system development, primary care units achieved the set goals across all indicators, with statistically significant differences at the 0.05 level in the transfer groups. Specifically, the group with a 100% transfer showed clear outcomes, with average results for all indicators exceeding 90%, indicating effective outcomes from the changes in primary health care according to public health policies and primary health care service standards [

2,

3,

4] aimed at developing and evaluating quality with a focus on equity and efficiency. The study identified additional factors affecting service provision related to decision-making in accessing basic health care, where nursing played a significant role in clearly developing the primary health care system found post-transfer to the PAO, with the greatest discrepancy from expectations, showing progress in job functions at 81.87%, a decrease from expectations, and a 53.80% reduction in indicators due to staff deficiencies, insufficient medical supplies, unlinked referral systems, and inadequate budgets. The study also found decreased self-care capabilities and inappropriate service behaviors [

6], consistent with the study by Peerpun P., and Pasunon P. [

23], that found problems and obstacles in health service provision at a sub-district health-promoting hospital in Uttaradit Province, noting issues such as inadequate and inconvenient service points, insufficient doctors and nurses, and unstructured service processes like lack of consultation points and information, and unclear community network participation. To overcome barriers to access, strategies should include improving the environment, increasing medical staff, integrating various health services, providing consultation channels and information to the public, and developing the capabilities of caregivers and community cooperation.

4.2. Nursing Practices

The study found that the majority of service recipients had high expectations and perceptions of quality response, with 97.50% and 89.75% respectively. The factors related to accessibility and the capabilities of nurses in sub-district health-promoting hospitals post-transfer, with the highest average competency being the role in promoting health at an average of 4.15 (SD=0.66) and the lowest in developing primary nursing quality at 3.76 (SD=0.81). This study highlights the complexities and possibilities in the interaction between cultural beliefs, information needs, and practical and logistical obstacles faced by health providers, such as supply procurement and client needs [

18]. Previous studies provide a basis for developing intervention strategies to overcome access barriers by identifying and analyzing supporting factors for health providers to respond to individual needs. The expertise of nurses is crucial; developing health personnel in the primary system is key to setting standards and enhancing nurse capabilities to ensure high-quality, efficient health care services. This study aligns with the experiences and daily needs of service recipients [

19,

24].

4.3. Quality of Care

The study noted that quality service provision emphasized outcomes and quality according to SERVQUAL and QOF criteria, comparing outcomes by indicators of primary care units before and after transfer in the group that was 100% transferred, noting a decrease in outcomes post-transfer with statistically significant differences at the 0.05 level. Comparing outcomes by various indicators before and after transfer (n=342) revealed significant statistical differences at the 0.05 level across all indicators. This confirms data from previous studies that identified significant factors affecting access or operational barriers to basic health care for skilled individuals, such as confidence in attitudes and belief systems, dealing with information, and practical and logistical obstacles. However, the focus of service providers is crucial and not reported concerning the various aforementioned aspects. In reality, primary data from some studies, including reports or examples of beneficial experiences, such as in the study by Grut et al. [

24], found that health provider attitudes are barriers and are perceived as significant when necessary. Examples and discussions of outcomes, related problems, and impacts on the complex and severe system of health-seeking processes, thus, key goals in developing the quality of services in future units should focus on responding to the needs and beliefs of service recipients and managing practical and logistical constraints to ensure effective and high-quality health care access.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Impact on Service Quality

The transfer of sub-district health-promoting hospitals to provincial administrative organizations resulted in significant changes in service quality and outcomes. The study revealed that full transfers (100%) demonstrated clear decreases in service quality across several performance indicators, significantly differing from expected outcomes.

5.2. System Development and Nursing Practices

System development goals were generally met, but there were disparities in expectations and actual outcomes, especially in fully transferred groups. Nursing practices and role efficacy varied significantly, indicating both challenges and areas of effective performance post-transfer. Barriers to Effective Service Delivery: Key barriers identified included insufficient staffing, inadequate medical supplies, unlinked referral systems, and insufficient budgeting. These factors critically hindered the ability of hospitals to meet health service demands effectively.

Implications for Practice: Policy and Management: There is a critical need for provincial administrative organizations to enhance strategic planning and resource allocation to ensure that health services are adequately supported. Effective policy oversight and comprehensive service standards should be established to guide the operational processes and improve service delivery. Capacity Building: Continuous professional development and training for nursing staff and other health professionals should be prioritized to address the gaps in service provision and improve overall care quality. Community Involvement: Increasing community engagement and transparency about health service provisions can help align service delivery with local needs and expectations.

Recommendations for Future Research; Longitudinal Studies: Future studies should consider longitudinal designs to track the long-term effects of hospital transfers on service quality and patient outcomes. Comparative Studies: Further research comparing different degrees of transfer (e.g., less than 50%, 50-99%, and 100% transfer) could elucidate more nuanced impacts on service quality and operational effectiveness. Qualitative Research: Qualitative studies focusing on the experiences and perceptions of both service providers and recipients before and after hospital transfers would offer deeper insights into the challenges and opportunities presented by such policy changes. Final Thoughts: This study underscores the complex dynamics involved in transferring health service management to provincial administrative organizations. While the intent behind such transfers is often to enhance efficiency and service delivery, the actual outcomes can vary significantly, influenced by multiple operational, cultural, and logistical factors. Addressing these challenges through informed policy decisions, strategic management, and continuous stakeholder engagement is essential for improving health outcomes in the community.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AS and CS; Methodology: PS, BN, MC, BK,AS; Software: PS, BN, MC; Validation Formal Analysis: AS, CS, PS, BN, MC, BK,AS; Investigation: PS, BN, MC, BK,AS; Resources; Data Curation: AS, CS, PS, BN, MC; Writing-Original Draft Preparation: AS, CS, PS, BN, MC; Writing- Review & Editing: AS, CS, PS, BN, MC, BK,AS; Visualization: PS, BN, MC, BK,AS; Supervision: AS; Project administration: AS, CS, PS, BN, MC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received financial support from the HSRI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval and consent to participate. This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee for Research in Human Subjects at Hua Hin Hospital, under project number RECHHHNo.011/2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data was created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author’s contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Jirabunlue, T.; Tossawong, S.; Pithayarangsit, S.; Sumalee, H. Power distribution in international health: A study of perceptions before and after decentralization. J Health Syst Res. 2010, 4, 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Decentralization of Power to Local Authorities. Plan for decentralization of power to local authorities in the year 2000. Royal Gazette, Special Issue, 17 January 2001. [in Thai].

- Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand. Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand B.E. 2540. Royal Gazette. 1997 Oct 11;114(55A). [in Thai].

- Office of Health System Support. Manual for developing Tambon Health Promotion Hospitals (THPH) in 2021. 2020 Jun 20. Available from: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1aCDXtrAjIYPlDgn403Jz-d_6fEWp4U3J/view [in Thai].

- Ghuman, B.S.; Singh, R. Decentralization and delivery of public services in Asia. Policy Soc. 2013, 32, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobos Munoz, D.; Merino Amador, L.; Monzon Llamas, L.; Martinez Hernandez, D.; Santos Sancho, J.M. Decentralization of health systems in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leetavechsuk, S. Service quality assessment of provincial health facilities in Prachuap Khiri Khan Province. J Health Syst Res. 2014, 8, 93–102, Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/11228/4004 [in Thai]. [Google Scholar]

- Thitipat, P.; Chaotip, B.; Warangkana, J. Success in the operation of Tambon Health Promotion Hospitals in Kanchanaburi Province. Acad J Community Public Health 2019, 5, 63–63, Available from: https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/ajcph/article/view/247297 [in Thai]. [Google Scholar]

- Manee-rat, P.; Piyanutsakorn, N. Evaluation of service delivery by primary care units meeting the service standards of provincial health service. UDH Hosp Med J. 2020, 28, 295–305, Available from: https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/udhhosmj/article/view/248507 [in Thai]. [Google Scholar]

- Nursing Council. Announcement of the Nursing Council on standards for nursing and midwifery services at the provincial level. Royal Gazette. 2005, 122(62A). Available from: https://www.tnmc.or.th/images/userfiles/files/P123.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- Policy and Strategy Bureau, Ministry of Public Health. National Strategic Plan 20 years (Health). 2016 Jun 22. Available from: https://waa.inter.nstda.or.th/stks/pub/2017/20171117-MinistryofPublicHealth.pdf [in Thai].

- Daniel, W.W.; Cross, C.L. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences, 9th ed.; Wiley: 2018.

- Chaiyachon, I.; Prajusilapa, K. The study of the role of nursing professionals in Tambon Health Promotion Hospitals. Mil Med J. 2018, 19, 193–202, Available from: https://he01.tcithaijo.org/index.php/JRTAN/article/download/164695/119359/ [in Thai]. [Google Scholar]

- Van Belle, G.; Fisher, L.D.; Heagerty, P.J.; Lumley, T. Biostatistics: A Methodology for the Health Sciences; John Wiley & Sons: 2004.

- Saengthong, K.; Kotaranon, P.; Tangkleiang, B.; Noothong, S.; Thepraksa, N. Factors affecting service quality influencing the decision to choose the service of Naban Hospital, Nakhon Si Thammarat Province. Local Adm J. 2020, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.L. Delivering quality service: Balancing customer perceptions and expectations; Simon and Schuster: 1990.

- Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.L.; Zeithaml, V.A. Guidelines for Conducting Service Quality Research. Mark Res. 1990; 2(4). [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, J.-F.; Harris, M.F.; Russell, G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 19. WHO global disability action plan 2014–2021. Better health for all people with disability, WHO; 2015. [cited 2020 Apr 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/disabilities/actionplan/en/.

- Speziale, H.S.; Streubert, H.J.; Carpenter, D.R. Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 2011.

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handbook of qualitative research. 2nd ed. 1994, 105, 163–194. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo qualitative data analysis software. Version 10. 2012.

- Peerapan, P.; Pasunon, P. Factors Affecting the Appropriateness of Health Service Guideline for People in a Sub-District Health Promotion Hospital Context in Muang District, Uttaradit Province: Mixed Method Approach. J Manag Dev Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat Univ. 2021, 8, 123–135, Available from: https://so06.tci thaijo.org/index.php/JMDUBRU/article/view/249718 [in Thai]. [Google Scholar]

- Grut L, Sanudi L, Braathen SH, et al. Access to tuberculosis services for individuals with d isability in rural Malawi, a qualitative study. Mancinelli S, editor. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0122748. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).