1. Introduction

The world’s older population is steadily increasing and the proportion of those aged 60 is expected to almost double from 12% to 22% by the year 2050 [

1]. In light of these demographic changes, and with an increase in the number of older employees and the lengthening of their working years, researchers have begun to take an interest in the associations linking employee’s age, work productivity, and psychological well-being with people’s attitude towards older workers (for a review, see [

2]).

Ageism, the way people think (stereotypes), feel (prejudices), and behave (discrimination) towards others because of their older age, is a common problematic social phenomenon [

1]. An older person may often be perceived as incompetent, slow, and fragile [

3]. According to the Stereotype Embodiment theory [

4], ageist attitudes are prevalent in society and are internalized from childhood, due to continuous exposure to common beliefs and prejudice held towards older adults. These perceptions might even be directed towards oneself when a person reaches old age. This phenomenon of ‘self-ageism’ is linked to the way the individual perceives aging in general, and to his or her personal aging experience. Such negative aging perceptions may adversely affect physical health and well-being of older adults, as well as their cognitive functions and longevity [

3,

5].

Age-related discrimination in the workplace. Ageism in the workplace is manifested in individual or institutional (formal or informal) labeling and discrimination against employees due to their advancing age. Despite the fact that discrimination based on age is prohibited by law in many countries (for example in Israel; [

6]), and in spite of the difficulty of estimating the exact extent of this type of discrimination, it seems to be a widespread phenomenon. The percentage of employees who experience discrimination at work ranges from 48.1% [

7] to 91% [

8]. MIDUS (Midlife in the US), an extensive longitudinal study on old age conducted in the US, indicated that 81% of employed people aged 50 and over reported experiencing age discrimination in the past year [

9]. Recently, age discrimination in the high-tech industry has also been reported. An accelerated momentum of automation and digitization caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, has resulted in an increase of the threshold conditions for positions in industry. This, in turn, has made it harder for the middle-aged population to enter the labor market [

10]. In addition, hiring managers tend to rate programmers aged 45 and older as less suitable for the job, which may also stem from the assumption that older workers are unable or are unwilling to try new technologies [

11].

In general, older employees are perceived as being inflexible, and as tending to avoid changes, or as having low ability to acquire new skills compared to younger workers [

12]. It was also found that managers with negative ageist views tend to think that older workers should retire earlier [

13]. Age discrimination manifests itself in the prevention of promotion in the workplace and a general preference for hiring young people [

14,

15]. On the other hand, it was found that older workers are positively labeled as more loyal and trustworthy compared to their younger colleagues [

16]. These findings are worrisome considering the increasing proportion of older workers, which will expose a cumulative ratio of older employees to negative and discriminatory treatment.

The current study focuses on a specific aspect of ageism at work, which has received scant attention in the research literature: older employees’ subjective attitudes and perceptions of age discrimination in the workplace. Studies have found negative relationships between perceived age discrimination and self-efficacy [

17], organizational commitment, work involvement, and life and work satisfaction [

18,

19]. In addition, it was found that the more the employees felt discriminated against at work due to their age, the more they reported a tendency to look for other ways of earning a living or to retire from work [

20]. In general, discrimination at work—of any kind—is a stressful factor, which is associated with increased levels of depression and anxiety, as well as with reduced levels of psychological well-being and life satisfaction [

21,

22].

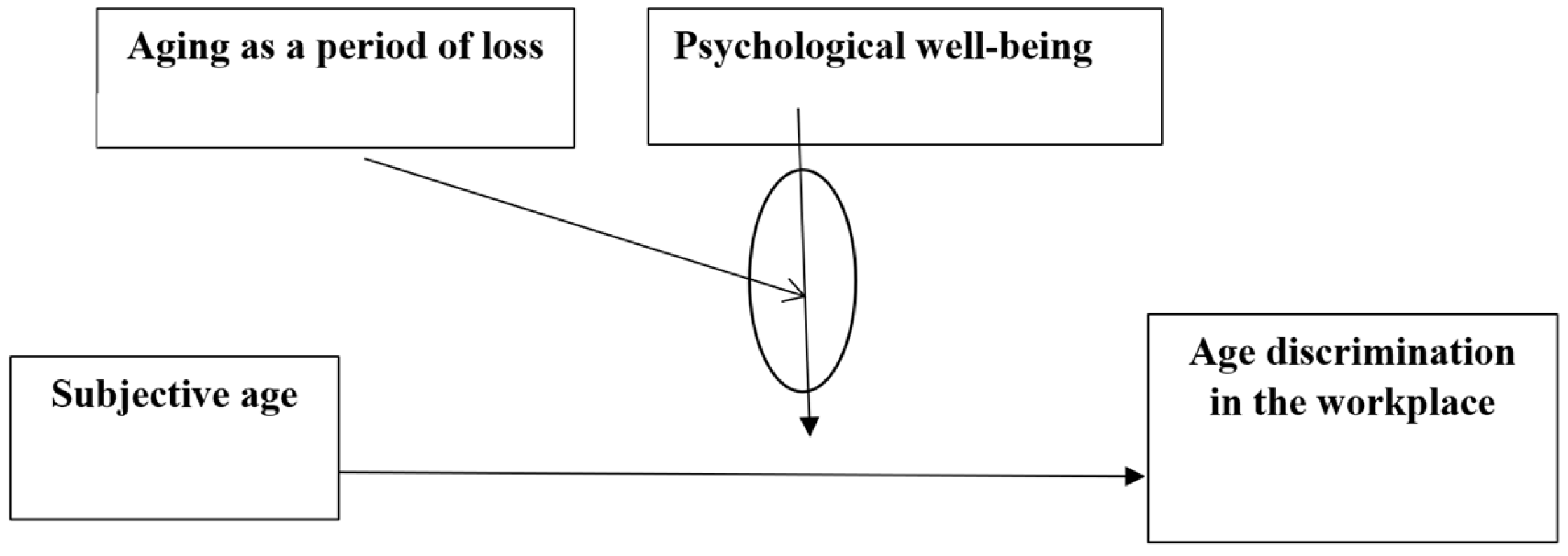

Do employees with lower levels of psychological well-being perceive themselves as being more discriminated against at work because of age? Can negative and positive perceptions of aging lead to higher and lower (respectively) levels of self-perceptions of age discrimination in the workplace? Can the combined effect of psychological resources, such as positive perceptions of one’s aging and his/her well-being affect self-perceptions age discrimination at work? These questions will be explored later, and the study will analyze a conceptual and statistical model incorporating six research hypotheses, along with a moderated moderation model (see

Figure 1; [

23]).

Psychological well-being and age discrimination in workplace. Psychological well-being is a broad term that reflects the existential challenges the individual faces and his/her potential for optimal functioning in his/her life. The importance of referring to the individual’s psychological well-being as a mental resource is expressed in the World Health Organization’s report referring to the term mental health as a state of psychological well-being through which the individual fulfills his potential, can cope with the pressures of normal life, can work in a healthy and productive manner, and is able to contribute to himself and his community [

24]. Carol Ryff described this concept using a model consisting of six dimensions: autonomy, personal growth and development, environmental mastery, positive relationships with others, purpose and meaning in life, and self-acceptance [

25,

26].

Rate of psychological well-being is measured throughout life, and there seems to be a decrease in the personal growth and development and the purpose and meaning in life measures as chronological age increases [

25,

27,

28]. Psychosocial research has proven that despite the decline in psychological well-being in the second half of life, positive functioning with regard to meaning and purpose over the life course, as well as a capacity for self-acceptance both have a positive effect on employed people, reducing the chance of illness and improving quality of life [

29,

30,

31].

Over the last three decades, psychological well-being has been examined around the world through hundreds of studies. A growing body of research examined the link between well-being and physical health (e.g., [

32,

33]), with comparatively less attention directed towards investigating the link between well-being and ageism. Effective intervention programs have been developed in the spirit of the Ryff’s model [

34,

35], some of which have been effectively implemented in workplaces [

36]. Longitudinal studies have found that a positive relationship exists between psychological well-being and mental and physical health [

37,

38]. One longitudinal study on 5,500 Americans (65.7% still working) found that among 51-56-year-olds, who reported lower levels of psychological well-being, there is a high probability of developing depression after a decade [

39]. According to a study conducted specifically among older women with high psychological well-being [

40], encouraging biological indicators such as low cortisol values (a proxy measure of stress), low risk of heart disease, and enhanced sleep quality were found. Similarly, a review study that sampled over 136,000 participants, whose average age was 67, found that among those who scored high on the purpose-in-life component, there were lower rates of heart disease and mortality [

41]. Taking all of the above into account, it would seem that psychological well-being contributes to better quality of life, and perhaps even to an extended life expectancy. In addition, higher employee psychological well-being has also been associated with effective functioning and higher productivity of organizations and workplaces [

42,

43,

44]. Therefore, organizations and institutions have begun to work towards the advancement of employees through changes in public policy [

45].

Despite the cited studies, there is a dearth in the literature of studies that examine the nature of the relationship between psychological well-being and perceptions about age discrimination in the workplace among older employees. On the other hand, the relationship in the opposite direction was examined, and these studies found that positive work perceptions predict higher psychological well-being [

46]. Moreover, prior research found a negative relationship between discrimination at work and respect towards older workers which, in turn, is associated with higher psychological well-being. In this study conversely, discrimination at work was associated with job insecurity which, in turn, was found to be associated with lower psychological well-being [

47]. In conclusion, lower levels of discrimination at work were negatively associated with stress, insecurity, and the tendency to retire from work; and positively associated with appreciation of older employees, commitment to work, and life satisfaction. Therefore, the first research hypothesis proposed is that in the second half of life, higher levels of psychological well-being would be associated with less reported age discrimination at work.

Subjective age and age discrimination in workplace. Young subjective age (i.e., self-assessment of one’s age as younger than one’s chronological age) is a resource used by older adults to help them cope with health problems, losses, and negative cultural views on older adults [

48,

49]. Thus, it can be assumed that this resource is used by older employees who are exposed to age discrimination. An extensive review of studies carried out in 148 countries shows that, in general, people aged 40 and over attribute themselves a younger age [

50]. The reasons for this attribution stem from biological (physiological condition) and socio-psychological motives (the way society and the individual perceive old age and self-aging, and the degree of exposure to age discrimination, which is a social stress factor) [

51]. Young subjective age has been associated with better subjective and objective physiological and cognitive performance, and better health, longevity, and psychological well-being [

52]. Likewise, younger subjective age is also associated with higher levels of life satisfaction [

53], and predicts higher levels of psychological well-being [

54].

In recent years, there has been interest in empirical and theoretical research about employees’ perceptions of their subjective age. Research shows that young subjective age has a positive effect on motivation at work and contributes to easing stress—both at work and outside of work [

55,

56]. A longitudinal study found that a decrease in subjective age predicted an increase in control and motivation at work [

57]. Moreover, a daily diary study reported that older employees, who attributed an older subjective age to themselves, tended to attribute negative work events to their chronological age (“It happened because of my age”). In this study, workers with a younger subjective age attributed fewer negative events to their age and reported higher levels of attachment and commitment to work, together with increased psychological well-being [

58]. Therefore, the second research hypothesis is that a younger subjective age would be associated with less reported age discrimination at work.

Self-perception of aging and age discrimination in workplace. Various theories have dealt with the psychosocial process of aging in view of the physical and social challenges that intensify with increasing age (e.g., see [

59,

60,

61]). In this context, Baltes and Lang described sensorimotor, cognitive, personality, and social resources that enable successful aging [

59]. Laura Carstensen proposed the socio-emotional selectivity theory [

60], which propounds that with increasing age, better emotional regulation capability develops. As a result, older adults develop a richer sense of emotional complexity, which combines positive and negative emotional experiences. Susan Charles developed the theory of strength and vulnerability, and claimed that older people try to avoid negative stimuli, because when they are exposed to high levels of emotional arousal, they are more vulnerable than younger people and find it more difficult to recover their emotional and physiological balance [

61].

The main insights that can be derived from these theories are that the shortening of time remained to live, and the constant exposure to the natural losses that often accompany the aging process (e.g., death of closed ones, cognitive and physical decline) all lead to a complex coping and adaptation process. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the view of one’s own aging as a period of losses may affect the way people experience age discrimination at work.

More specifically, when examining how older employees perceive age-based discrimination, Charles’s theory of strength and vulnerability [

61] can be used. Hence, we assume that when older employees attempt to avoid events that will expose them to negative stimuli (such as age-related discrimination regarding their work performance), they may experience a great deal of vulnerability. When they fail to avoid such stimuli, they may self-internalize the negative labeling associated with “older employees” and behave accordingly. Offensive interpersonal behavior—such as incivility on the part of managers and colleagues or ageism at lower levels of intensity, such as harassment or a lack of respect due to age [

62] may provoke reactions of stress, undermine older employees’ sense of occupational security, and damage their general functioning and psychological well-being.

And yet, we would like to suggest that cultivating a subjective perception of positive aging—which perceives aging as a natural process that includes self-acceptance of the disadvantages and advantages, the losses and the gains—may serve older employees by helping them to cope with age-related discrimination. Indeed, the research provides some support for this claim. For example, a study examining the relationship between perceptions of old age and subjective age found that those aged 50 and over, who held positive perceptions of old age, also demonstrated a lower chance of experiencing age discrimination [

63]. In contrast, perceptions of age discrimination were found to be associated with a more negative perception of old age [

64], an older subjective age [

51], more depressive symptoms, lower levels of job satisfaction, and reduced subjective health [

65]. Therefore, the third research hypothesis proposed is that in the second half of life, a relationship would be found between more positive perceptions of old age, (i.e., a lower tendency to perceive old age as a period associated with losses), and lower levels of perceived age discrimination in the workplace.

How do the three above-mentioned psychological resources relate to one another and to discrimination at work? Studies have found that life satisfaction, which is one of the components of psychological well-being [

66], was associated with a younger subjective age [

67] and with more positive perceptions of aging. It was also related to taking preventive actions and improving health, such as exercising and avoiding smoking [

68]. Similarly, a longitudinal study found that older subjective age predicted less life satisfaction, when perceptions of aging were less positive, but not when perceptions of aging were more positive [

69]. A similar finding was reported in an experimental setup that included two manipulations. In the first, participants felt older through a blurred visual stimulus; in the second, perceptions of aging were activated by reading sentences that included positive (“smart”) or negative (“weak”) age labels. Participants who felt older reported lower levels of life satisfaction when exposed to a stimulus evoking negative perceptions of old age, but not when positive perceptions of old age were activated in them [

70]. This pattern indicates the significant effect of negative perceptions of old age on psychological well-being, compared to the more moderate effect of positive perceptions.

In light of the literature suggesting the existence of an independent contribution of each of these three mental resources to the perception of age discrimination at work, a uniform line is proposed for the interactive effect of these resources, which is based on a concept of compensation, rather than accumulation. According to the compensation approach, the existence of one resource compensates for the paucity of another resource and will therefore be more pronounced. This means that the resource’s contribution to a lower perception of age discrimination at work will be stronger when the additional resource or resources are weaker. Accordingly, the fourth research hypothesis, which is a two-way interaction hypothesis, proposes that young subjective age will contribute to reported age discrimination in the workplace—particularly among individuals with lower psychological well-being, but not as much among individuals with high psychological well-being. Similarly, the fifth research hypothesis, which is also a two-way interaction hypothesis, proposes that young subjective age will be associated with reported age discrimination in the workplace—particularly among those who perceive themselves as having experienced more losses due to old age. However, young subjective age will not contribute as much to reported age discrimination at work, among individuals who perceive the concept of old age as involving fewer losses. Finally, in accordance with this uniform line, the sixth research hypothesis, which is a three-way interaction hypothesis, suggests that young subjective age will contribute to less age discrimination at work particularly among individuals who report lower levels of psychological well-being and more losses in old age. In contrast, subjective age will not contribute as much to less reported age-related discrimination at work among individuals who are equipped with one or both of the following two resources—higher psychological well-being and lower perception of aging as a period of loss.

Hypotheses. Three main effects will be discerned, that is, (H1) higher psychological well-being, (H2) younger subjective age, and (H3) lower perception of aging as a period of psychological losses, and each will be associated with lower workplace age discrimination. Two 2-way interactions were also hypothesized: (H4) Psychological well-being will moderate the association between subjective age and workplace age discrimination, so that among participants with lower psychological well-being, the older the subjective age the higher the workplace age discrimination would be reported; (H5) Perception of aging as a period of psychological losses will moderate the association between subjective age and workplace age discrimination so that among participants with higher perception of losses, the older the subjective age is the higher the reported workplace age discrimination. Finally, a 3-way interaction was hypothesized: (H6) Psychological well-being and the perception of aging as a period of psychological losses will moderate the association between subjective age and workplace age discrimination, so that among participants with lower psychological well-being and higher perceptions of losses, the older the subjective age the higher is the reported workplace age discrimination.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations for the study variables are presented in

Table 1. In general, the mean level of workplace age discrimination was low, the mean level of subjective age tended to be younger the actual age, and the mean level of psychological well-being in the current sample tended to be high. Several notable correlations can be seen in

Table 1.

Table 2 presents the findings of the hierarchical regression analysis which examined our hypotheses. Workplace age discrimination was regressed on all variables.

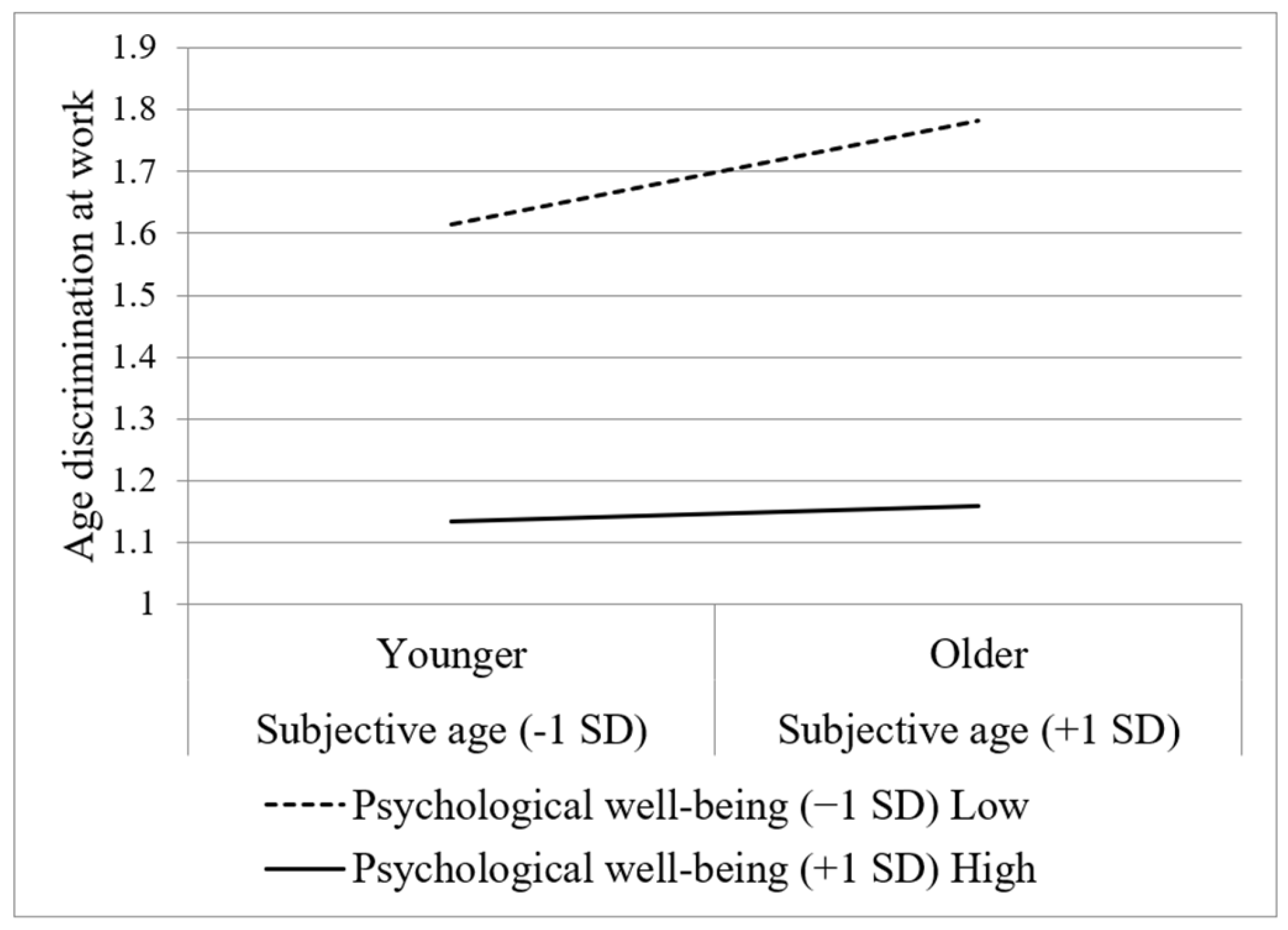

In step 1 it was regressed on background variables (controlling for covariates). Gender, education and self-reported health were negatively associated with workplace age discrimination (being a man, reporting higher education and reporting better health were significantly associated with lower levels of workplace age discrimination). In step 2 it was also regressed on the three independent variables. While and older subjective age only tended to be nearly positively associated with higher workplace age discrimination (Subjective age: B = 0.065, β = 0.070, p = 0.075), higher psychological well-being (Psychological well-being: B = -0.371, β = -0.371, p < 0.001), and the perception of aging as a period of less psychological losses (Aging as a loss: B = -0.113, β = -0.124, p < 0.01) were negatively associated with the perception of workplace discrimination. Therefore, hypotheses 1 and 3 were confirmed, while hypothesis 2 was not supported by the findings. Out of the three respective two-way interactions (between psychological well-being and subjective age; between subjective age and aging a period of psychological losses; between psychological well-being and aging a period of psychological losses), only the psychological well-being and subjective age interaction was significant (B = −0.67, β = −0.107, p < 0.05).

Figure 2 is presenting the results of probing this interaction. When probing this two-way interaction, it was demonstrated that while participants who reported lower psychological well-being (-1 SD) had a significant positive relationship between subjective age and workplace age discrimination (B = 0.169, p < 0.001; the steep black dashed curve), among participants who reported higher psychological well-being (+1 SD), the negative relationship was insignificant (B = 0.026, p = 0.5922; the black dashed line which is in parallel to the X axis). Moreover, from

Figure 2 it can be seen that there is a clear main effect for psychological well-being (B = −0.376, p <.0001), showing that the reported level of age discrimination at work among participants who reported higher psychological well-being is low (no matter what is their subjective age), whereas the level of age discrimination at work among participants who reported lower psychological well-being is high, and grows higher, as their subjective is older. This two-way interaction was qualified by a three-way interaction of subjective age, psychological well-being, and perception of aging as losses (B = −0.095, β = −0.190, p < 0.001).

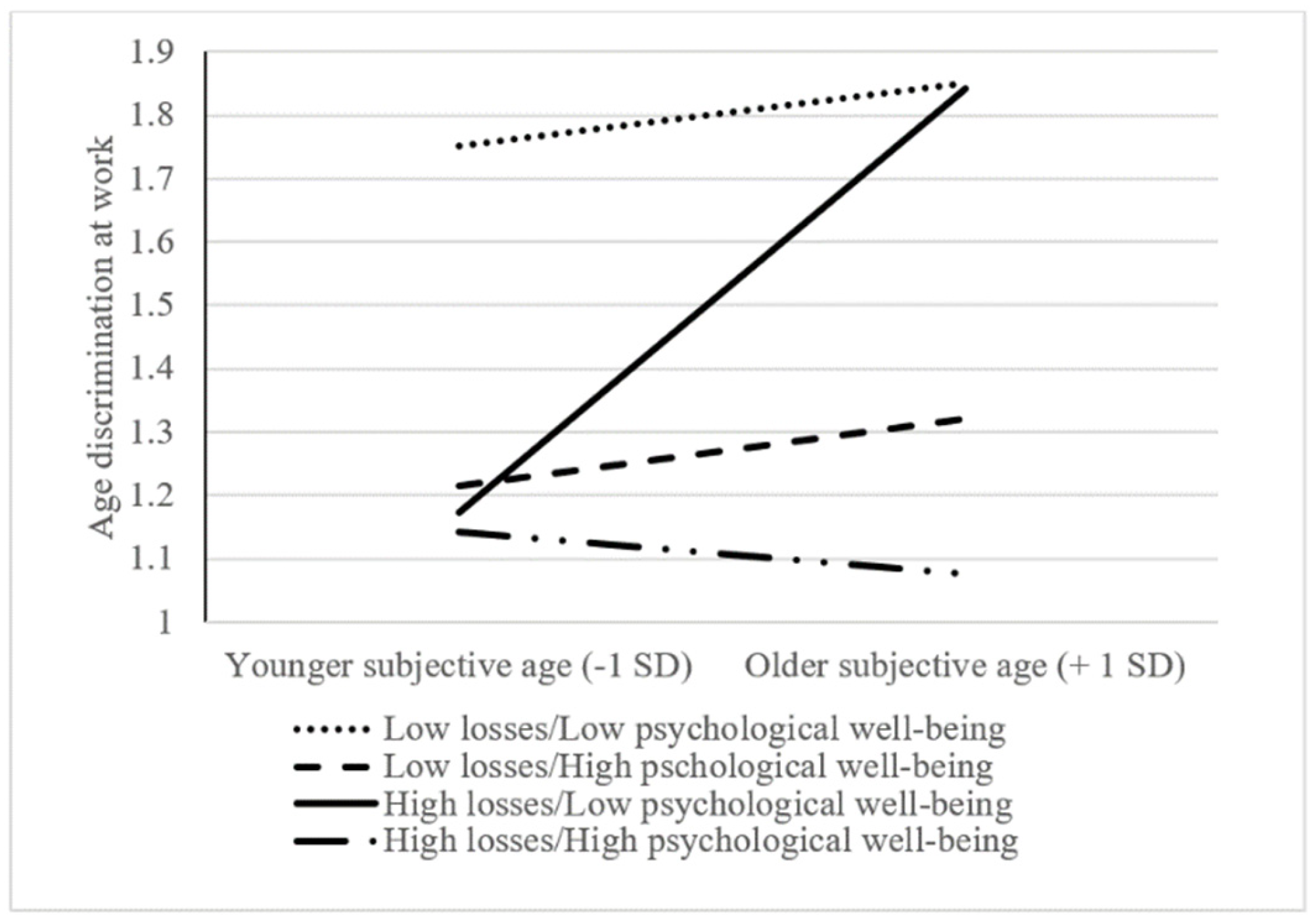

As depicted from

Figure 3, only the steep black curve demonstrated significant positive association between subjective age and age discrimination at work (the older the subjective age is, the higher the perception of age discrimination at work; B = −0.381, p < 0.0001). The steep black curve is depicting participants reporting both higher psychological losses and lower psychological well-being, i.e., the most vulnerable participants. It can also be noted that while participants reporting lower psychological well-being and low perception of aging as a period of psychological losses (the curve with points) demonstrate the highest workplace age discrimination, no matter what their subjective age is, it is the combination of participants who are also reporting the perception of aging as a period of psychological losses which is responsible for the positive relations between subjective age and age discrimination at work. The other three curves (the curve with points, the dashed curve and the curve with dashes and points) are almost parallel to the X axis, and do not demonstrate significant associations between subjective age and age discrimination at work. The observation of these three curves and the probing of the 3-way interaction show that when psychological well-being is high (B = 0.068, p = 0.390) or the perception of aging as a period of psychological losses is low (B = 0.062, p = 0.262), or when psychological well-being is high and psychological losses is low (B = -0.042, p = 0.4359)- in all these three cases, the relations between subjective age and age discrimination at work are insignificant.

In sum, while hypotheses 2 (subjective age would be positively associated with workplace age discrimination) and Hypotheses 5 (the association between subjective age and workplace age discrimination would be moderated by the perception of aging as a period of psychological losses) were not supported, Hypotheses 1 and 3 (higher psychological well-being, and lower perception of aging as a period of psychological losses will be associated with lower workplace age discrimination), 4 (the association between subjective age and workplace age discrimination would be moderated by psychological well-being), and 6 (the association between subjective age and workplace age discrimination would be moderated by the combination of psychological well-being and the perception of aging as a period of psychological losses) were supported.

4. Discussion

The current study sought to examine the contribution of three psychological resources among adults at the second half of life reporting age discrimination in the workplace. The research findings reveal that two resources (psychological well-being, and the perception of old age as a period of losses) contribute to the perceived age-related discrimination in the workplace, and that when examining the combined effects of these resources on perceptions of age-based discrimination at work psychological well-being is the most significant resource.

Regarding the main effects hypotheses, the negative relationship between and age discrimination at work (more well-being, less discrimination) was highly significant (H1), the positive relationship between subjective age and age discrimination at work had marginal significance (H2). The same holds true regarding the positive relationship between the perception of old age as a period involving losses and perceived age-based discrimination in the workplace (fewer losses are perceived, less perceived age-based discrimination, H3).

In line with previous studies, it was found that higher psychological well-being was associated with a lower perceptions of age discrimination at work. A previous study also found that higher psychological well-being was associated with lower levels of age-based discrimination in the workplace, when there was also a sense of appreciation towards the older workers in the work environment [

74]. Moreover, findings showed that employees with high psychological well-being at any age enjoy better mental and physical health [

54,

74], and function more effectively in the workplace [

44]. Therefore, organizations encourage the cultivation of employees’ well-being in order to achieve higher productivity at work [

45].

The importance of psychological well-being as a resource that moderates the perception of ageist discrimination in the workplace is particularly expressed in the confirmation of H4, which proposed that the relationship between subjective age and age discrimination in the workplace will be moderated by psychological well-being. The findings point to the possibility of interpreting the results through a compensation model. That is, availability of one resource (subjective age or psychological well-being) makes redundant the contribution of the other resource regarding the perception of age discrimination in the workplace. We hypothesized that among those who reported lower psychological well-being, the younger the subjective age was perceived, the less age discrimination at work was reported. Conversely, among those with high reported psychological well-being a low rate of age-based discrimination at work will be found—regardless of whether they felt younger or older than their age.

Next, we will offer two causal speculative explanations for this finding—explanations that our cross-sectional design cannot support and requires further research. First, psychological well-being is not life satisfaction or mere happiness, but is based on the

eudaimonia philosophy devised by Aristotle, according to which the happy person is the good person, who brings forth that which is hidden within himself [

26]. Further to this conceptualization, it was found that older people (most of whom are retired) attribute the fact that they have worked throughout their lives as being related to higher levels of psychological well-being [

46]. In other words, the workplace is the environment where the individual consistently grows on a personal level. Environment where a person develops independence and new skills, gains knowledge, learns about and acknowledges personal qualities as well as weaknesses. Environment where a person derives meaning in life through daily activities. In the second half of life, this development perhaps gives the employee—who can already envision the end of ones’ professional career—a sense of value that protects him/her against the development of a perception of age discrimination at work. It is also possible that such an employee receives appreciation and recognition in terms of a self-fulfilling prophecy, and therefore also perceives him/herself as suffering less from age discrimination in the workplace.

Consistent with this line, studies have found that people with higher levels of psychological well-being are more efficient at work and their wages are higher, compared to those who report lower levels of psychological well-being (for a review, see [

82]). In a related manner, higher meaning in work was found to be associated with general overall well-being [

83]. Moreover, a positive link was found between generativity (i.e., where one’s concern focus on the others such as co-workers, peers, and community) and higher satisfaction in life. This link was found to be mediated via increased meaning in work [

84]. Therefore, it is likely that employees with high levels of psychological well-being are also valued and appreciated, and perceive themselves as having self-worth, self-confidence, ascribe meaning to their work, and suffer less from age discrimination at work.

It is possible that the weak support for hypothesis 2 indicates that young subjective age is much more strongly related to perceptions of mental and physical health [

52,

85] than to perceived age discrimination in the workplace. In other words, young subjective age reflects more of an actual physical experience of vitality and health, and may even stem more from biological variables such as telomere length and gray matter density in the brain [

86,

87], than from an effort to defend against social perceptions that perceive older adults as being less valued than younger people. In this context, it may also be possible that the degree of stability in the perception of subjective age is responsible for the perception of age-based discrimination. Thus, when there is no stable perception of age, there is a greater tendency to attribute events at work as being related to age discrimination. Support for this interpretation can be found in a study which showed that fluctuations in subjective age indeed predicted more such attribution among older workers aged 50-70 [

58].

However, it is possible that while subjective age as a single variable only marginally contributes to perceptions of age discrimination at work, negative stereotypical perceptions of older age that are internalized and become negative self-perceptions of aging, can contribute to an individual’s perception of older subjective age. After being exposed to negative stereotypes from a young age, people adopt a negative labeling towards old age, and eventually direct it towards themselves [

4]. In addition, they may attribute a young age to themselves starting from early adulthood [

51]. Thus, while subjective age can be indirectly affected by perceptions of age discrimination, it does not seem to directly contribute to these perceptions. This direction is supported by the findings of a study that inversely examined the contribution of the perception of age discrimination to an older subjective age. The relationship between these two variables was found to be indirect and mediated through negative self-perceptions of aging [

88]. Along these lines, we can also mention additional studies which found that this relationship also exists in the opposite direction. For example, a longitudinal study [

89] found that an improvement in the positive self-perception of aging led to a decrease in subjective age.

The findings of the present study also confirm H3, according to which lower levels of the perception that aging is a period associated with losses were linked to lower levels of perceived age discrimination in the workplace. Accordingly, a study that examined employees aged 50 and over (37.7% employees), found that participants who perceived their aging in a more positive way, reported less age discrimination [

63]. The authors raised the possibility that participants with a more positive perception of aging are less likely to assume that any form of abusive behavior towards them is due to their age. The relationship between the two variables is also in the opposite direction. A longitudinal study found that the experience of age discrimination at work predicted a decrease in positive self-perceptions of aging which, in turn, also led to an increase in depressive symptoms among older employees [

64].

In addition, it can be suggested that here, too, a self-fulfilling prophecy is taking place. When older workers have positive perceptions about aging, and when they clearly do not attribute their difficulties at work to the notion that old age is a time of losses, their co-workers act accordingly, and do not perceive them in the context of their older age. This positive interaction maintains the older employees’ perceptions of aging as involving less losses. Therefore, they are not discriminated against on the basis of age in the workplace. This serves to reinforce employees’ perceptions of positive aging, and so forth. In addition to this explanation, it should be remembered that the current study’s data were collected at a uniform point in time (because of its cross-sectional study design). Thus, the study design does not allow us to draw conclusions about the causality described in this explanation, which can only be examined through a longitudinal study.

In addition to these explanations, it can be argued that individuals with high levels of psychological well-being, who do not necessarily perceive aging as a period of losses, more strongly demonstrate the “positivity effect” [

90], which allows them to focus more on positive, rather than negative stimuli and even have more of a tendency to forget stressful events. For instance, among men aged 45-92, who were asked to recall stressful events from the past week (for example, a threatening event which made them feel worried), it was found that with increasing age, they tended to more easily forget stressful events, resulting in lower levels of stress [

91]. It was also found that participants who felt older reported less life satisfaction when they were exposed to a stimulus that evoked negative perceptions of old age, but not when positive perceptions of old age were activated in them [

70]. Therefore, these participants may simply choose to “ignore” or put less emphasis on age discrimination-related events at work, thereby enjoying enhanced psychological well-being. It is also possible that in the current study, those who did not necessarily perceive aging as a period of many losses, had more of a tendency to focus on positive stimuli and attributed less ageist behavior to age discrimination at work. It is recommended that follow-up studies will further test these hypotheses.

Our findings also support the importance of subjective perceptions of self-aging [

5], as they demonstrate that subjective perceptions of self-aging are related to decreased perceptions of age discrimination in the workplace. These resources are anchored in the stream of positive psychology. This approach not only emphasizes a person’s psychological well-being as a central factor in his quality of his life [

26], but also stresses the importance of views on aging to better understand the ways in which aging individuals cope successfully with their social environment [

92].

While the research findings show the importance of both psychological well-being and subjective perceptions of aging for the understanding of the phenomenon of perceived workplace age-discrimination of older adult, the brake-up of the moderated moderation model demonstrated, in accordance with H5 and H6, a compensation model.The model emphasized, first and foremost, the importance of high levels of psychological well-being as a kind of compensation for the lack of a younger subjective age and/or of the perception of old age as a period accompanied by less losses. According to the compensation model, high psychological well-being is sufficient to allow an individual to hold a low perception of age discrimination at work, while low psychological well-being will manifest itself in a perception of age discrimination at work—even if the individual holds a perception of young subjective age, or of old age as involving less losses. However, the triple interaction found in the study showed that the combination of low psychological well-being and the perception of old age as the life period involving the most losses sharpens the contribution of older subjective age to the perception of age discrimination at work. Thus, among those individuals who lack the other two resources, subjective age becomes a central contributing factor for workplace age-based perceptions.

Therefore, we understand that psychological well-being is an important defense against the perception of age discrimination in the workplace—its presence helps to minimize such perceptions, while its absence increases such perceptions. In the power relations between perceptions of aging and psychological well-being, it seems that in the context of age discrimination in the workplace, psychological well-being has the upper hand. In this context, further studies will be able to examine the mechanisms responsible for the connection and examine whether older employees, who enjoy a high level of psychological well-being, also maintain good employment relationships. The findings also demonstrate that when we examine the contribution of other perceptions of old age (subjective age and perceptions of aging) to perceived age discrimination at work, it is important to consider the individual’s psychological well-being.

The present study has several limitations. This is a preliminary cross-sectional study, which does not allow a causal directionality test between the tested variables. For example, it impossible to be certain whether subjective age is a predictor or outcome, because temporal precedence cannot be ascertained. [93] found that the relationship between subjective age and positive work and life outcomes (e.g., task performance, career and life satisfaction) are confounded by core self-evaluations (i.e., how people feel about themselves). Although their research did not investigate age discrimination at the workplace, future research may consider testing the importance of self-core evaluation in this context. Therefore, future research, using a longitudinal study design, is needed. Moreover, the tested age range was very wide, and the sample also included people who are no longer working. Admittedly, although previous studies that examined similar issues were also based on even lower percentages of employees [

63], and in spite of the fact that the age and the employment variables are controlled in all of the analyses, future studies are recommended to focus on narrower age ranges of older individuals who are still employed. In addition, the study was based on an Israeli sample; hence, there is a need for repeat studies that reproduce the same results in other cultures.

Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to show the combined contribution of psychological well-being and two perceptions of aging (subjective age and the perception of old age as a period of losses) in relation to age discrimination in the workplace. This study also clarifies the great importance of psychological well-being of older employees in their career, as a resource that can greatly improve their perception of their last years at work, and opens the door for many additional future studies on the subject.