Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a pressing public health concern in the United States, with approximately 2.5 million TBI-related emergency department visits; 288,000 TBI-related hospitalizations; and 61,000 TBI-related deaths reported each year (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). TBI is associated with high rates of disability, including limitations in performing basic activities of daily living (ADLs), such as bathing, dressing, eating, or toileting, and/or in performing physical tasks, such as mobility (Klima et al., 2019; Lo, Chan, & Flynn, 2021; Whiteneck, Cuthbert, Corrigan, & Bogner, 2016).

Community discharge is generally viewed as an indicator of high-quality health services provided in acute care settings (Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2019). Several studies have addressed the positive impacts of community discharge on patients, including higher levels of functional independence (Brown, Lee, Lennon, & Niewczyk, 2020; Souesme et al., 2022; Werner, Coe, Qi, & Konetzka, 2019), fewer cognitive or behavioral issues (Arya et al., 2022; Souesme et al., 2022), lower healthcare cost (Chevalley, Truijen, Saeys, & Opsommer, 2022; Werner et al., 2019), and enhanced quality of life (Arya et al., 2022; Olsson, Berglöv, & Sjölund, 2020). Occupational and physical therapy services during the acute stay have been associated with a higher rate of community discharge (Kanchan et al., 2018; O'Brien & Zhang, 2018; Roberts et al., 2016; Souesme et al., 2022; Thorpe, Garrett, Smith, Reneker, & Phillips, 2018).

Occupational and physical therapists in acute care settings analyze patients’ functional and physical performance limitations and gather other relevant information (e.g., living situation) to tailor treatment to enable a safe community discharge (Diane U. Jette et al., 2014). However, there is a lack of studies that provide empirical support for factors explaining the relationship between acute care occupational therapy (OT) and physical therapy (PT) utilization and discharge disposition.

A primary focus of acute care rehabilitation services is to improve patients’ functional and physical performance (Ejlersen Wæhrens & Fisher, 2007). Two acute care studies have found that rehabilitation services are associated with improved functional and physical performance in patients with TBI (Trevena-Peters et al., 2018; Zarshenas et al., 2019). Additionally, an increased frequency of rehabilitation services leads to greater functional and physical gains at the time of discharge from acute care among patients with TBI (Kanchan et al., 2018; Zarshenas et al., 2019).

Patients with TBI who have higher functional and physical scores may be more likely to discharge to the community, as higher functional and physical performance during acute care rehabilitation ideally translates into safe performance of daily activities and basic mobility within a patient’s home environment (D. U. Jette, Grover, & Keck, 2003). Several studies have examined the relationship between functional and physical status and discharge destination following acute care among patients with TBI, finding that TBI survivors who made larger functional and physical gains were more likely to be discharged to the community (Horn et al., 2015; T. O. Oyesanya, 2020; van Baalen, Odding, & Stam, 2008). To date, no study has examined whether functional and physical performance at discharge influences the relationship between acute care OT and PT services utilization and community discharge. Understanding potential mechanisms by which OT and PT utilization and community discharge are related may inform efforts to enhance the type or amount of acute care OT and PT services delivered to individuals with TBI to maximize safe community discharge.

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether the relationship between acute care OT and PT utilization and community discharge is moderated by functional or physical performance at discharge. We hypothesized that patients with greater OT and PT utilization would be more likely to have a community discharge and that this relationship would differ depending on patients’ functional or physical performances at discharge (e.g., patients with lower ability level would be less likely to have a community discharge).

Methods

Participants and Procedure

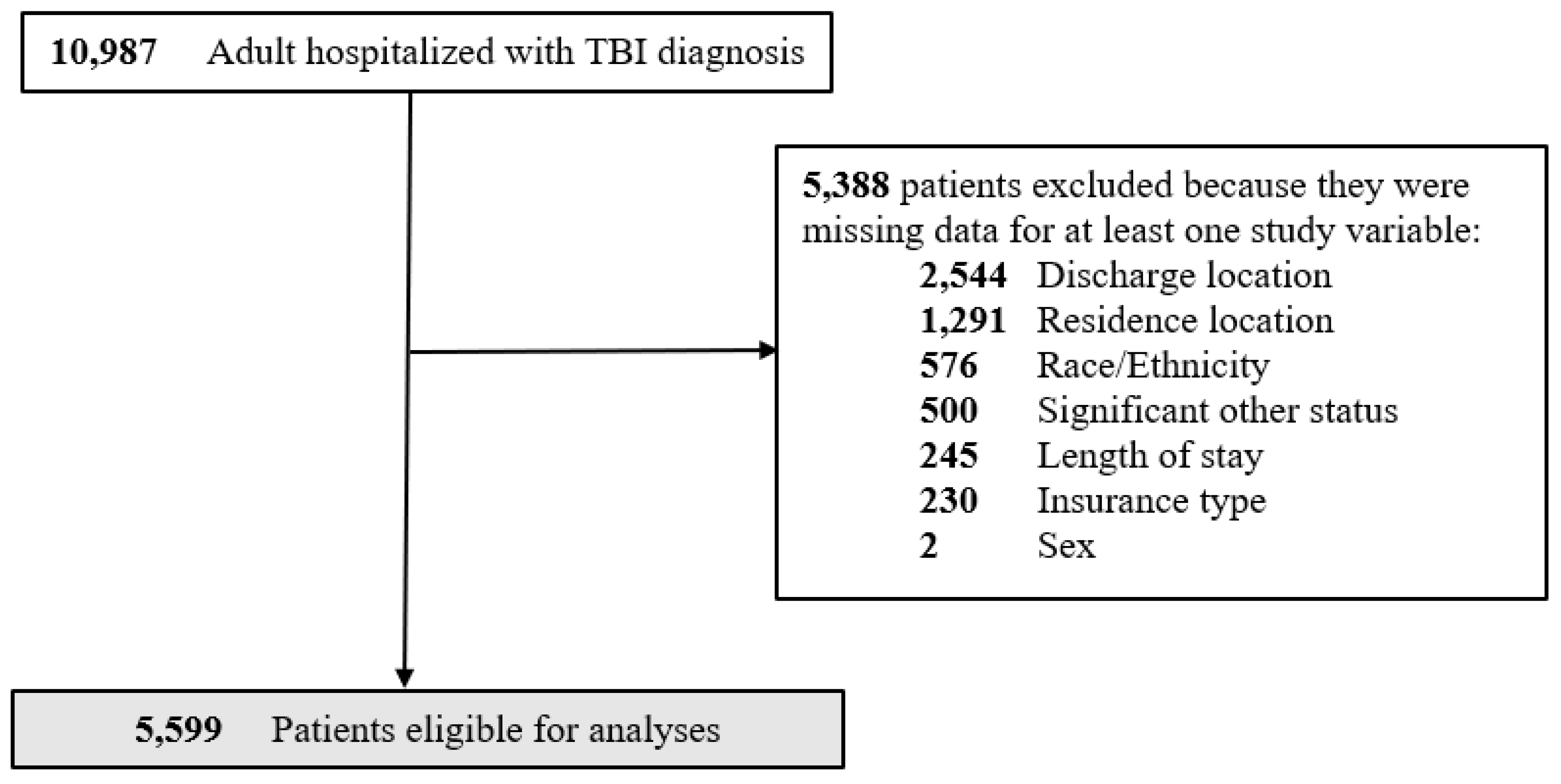

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study of de-identified electronic health record (EHR) data for patients admitted to 14 trauma centers, levels I to IV, within a single large health system in the state of Colorado. The study included EHR data from 401,350 patients admitted and discharged between June 2018 and April 2021. Inclusion criteria were an adult (aged ≥ 18 years), admitted to the hospital with a TBI diagnosis based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes for admission, and had at least one OT/PT evaluation/treatment session. We excluded patients who did not survive the hospitalization or were missing data on key variables of interest. These data were validated, de-identified, organized, and supported by the Health Data Compass Data Warehouse project (healthdatacompass.org). After applying the inclusion criteria, the final sample consisted of 5,599 adults (

Figure 1). A signed data-use agreement was in place, and the study was approved by the Colorado State University Institutional Review Board. The

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines were applied to this study (von Elm et al., 2014). See (

Appendix A) for more information about

STROBE statements.

Measures

OT/PT Utilization

OT/PT utilization was measured using service units billed for each OT or PT encounter (e.g., 1 unit = ≥ 8 minutes through 22 minutes) during the patient’s acute care stay. See (

Appendix B) for more details about the service units and their equivalent billed minutes.

Covariates

We included person-level factors such as age (years); sex (female/male); race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic, Multiple race, and Other [e.g., Asian, American Indian, Alaska native, native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander]); presence of a significant other (yes/no); insurance type (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid, VA, Others, and Private); length of stay (days); comorbidity burden (using Functionally relevant TBI Comorbidity Index [Fx-TBI-CI] (Kumar et al., 2022)), and TBI severity (e.g., Mild; Moderate; and Severe (Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, 2015)) as covariates. The Fx-TBI-CI is a method used to categorize patients’ comorbidities based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) diagnosis codes obtained from hospital administrative data (Kumar et al., 2022). The Fx-TBI-CI was calibrated based on the function of individuals with TBI receiving inpatient care (Kumar et al., 2022). We constructed a weighted summary index according to Kumar et al. to evaluate comorbidity burden (2022). We used ICD-10 diagnosis codes obtained from the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) to classify TBI severity as mild, moderate, or severe (Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, 2015).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (e.g., means, standard deviations, percentages) were calculated, both for the total sample and stratified by community discharge. We used bivariate analyses to examine unadjusted differences in patient characteristics between discharge groups: Chi-square, independent t-tests, and ANOVAs. Chi-square and ANOVA analyses were conducted to assess the association between the dependent variable (e.g., community discharge [yes/no]) and the independent variables. Chi-square tests were used for dichotomous variables, while or ANOVAs were applied to categorical variables with three or more levels. Independent t-tests were utilized to examine the association between all continuous variables and the dependent variable (e.g., community discharge [yes/no]). Multivariable moderation logistic regression models were used to assess the community discharge status as the dependent variable and rehabilitation services utilization (e.g., OT, and PT) and patients functional (i.e., ADL) or physical (i.e., mobility) performance at discharge as the main predictors of interest. In the OT model, we computed the main effect of OT utilization on community discharge, the main effect of functional performance (ADL) scores at discharge on community discharge, and the moderating effect of ADL scores on the relationship between OT utilization and community discharge by including an OT utilization-by-discharge ADL score interaction term. Similarly, in the PT model, we computed the main effect of PT utilization on community discharge, the main effect of physical performance (mobility) scores at discharge on community discharge, and the moderating effect of mobility scores on the relationship between PT utilization and community discharge by including a PT utilization-by-discharge mobility score interaction term. Estimates (e.g., odds ratios, confidence intervals) were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, presence/absence of a significant other, insurance type, length of stay, comorbidity burden, and TBI severity levels. Statistical significance was evaluated at α = .05 for all parameter estimates. All analyses were performed using R (Version 4.3.1) (R Core Team, 2023).

Results

Among the 5,599 patients included in the study, 67% were discharged to the community. The sample had a mean age of 54.7 years (

SD=20.2), with the majority being male (64%), White (72%), and having no significant other (58%). The most common insurance type was Medicare (39%), followed by Medicaid (26%). Most patients experienced moderate TBI severity (83%) (

Table 1). There were statistically significant differences between OT and PT utilization, and discharge ADL and mobility scores on community discharge (

p-values= <0.001 – 0.004). The mean OT utilization units were 4 (

SD=4.1) and the average discharge ADL score was 19.8 (

SD=4.3) (scores closer to 24 indicated that the patient requires no assistance). The mean PT utilization units were 5 (

SD=5.7) and the average discharge mobility score was 20.0 (

SD=4.3) (scores closer to 24 indicate that the patient requires no assistance). Results of the Chi-square and ANOVA analyses indicated statistically significant differences in community discharge for patients’ sex (χ²(1) = 22.9, p < 0.001), race/ethnicity (F(9.5, 6896.5)=7.7,

p-value= 0.01), significant other status (χ²(1) = 7.6,

p-value= 0.01), insurance type (F(412, 14683)=157, p< 0.001), and TBI severity groups (F(8.7, 873.8)=55.4, p< 0.001). Results of bivariate t-test analysis showed that there were statistically significant associations between various variables such as age (t(5597)=18.6,

p-value=0.02), length of stay (t(5597)=28.8,

p< 0.001), and comorbidity burden (t(5597)=19.6,

p< 0.001) with community discharge (

Table 1).

There was sufficient evidence to suggest that OT and PT utilization, and ADL and mobility score at discharge were good predictors of community discharge (

p-values <0.001) (

Table 2). OT and PT utilization illustrated statistically significant positive associations with the log odds of community discharge for patients who received OT (

= 0.19;

SE= 0.05;

p <0.001), and PT (

= 0.20;

SE= 0.03;

p <0.001). Patients' ADL and mobility scores at discharge demonstrated statistically significant positive associations with the log odds of community discharge for patients who received OT (

= 0.30;

SE= 0.02;

p <0.001), and PT (

= 0.32;

SE= 0.02; p <0.001). Both OT and PT interaction terms (i.e., OT utilization-by-discharge ADL score & PT utilization-by-discharge mobility score) showed a small but significant negative association with the log odds of community discharge (

= -0.01;

SE= 0.002;

p <0.001). Age demonstrated statistically significant negative associations with the log odds of community discharge for patients who received OT and PT (

= -0.02;

SE= 0.002;

p <0.001). Black and Hispanic patients were significantly and positively associated with the log odds of community discharge for patients who received OT (Black:

= 0.53;

SE= 0.19;

p-value=0.01; Hispanic:

= 0.39;

SE= 0.12;

p <0.001), and PT (Black:

= 0.48;

SE= 0.19;

p-value=0.01; Hispanic:

= 0.26;

SE= 0.12;

p-value=0.03) relative to their non-Hispanic White counterparts.

The presence of a significant other was significantly and positively associated with the log odds of community discharge for patients who received OT (

= 0.48;

SE= 0.09;

p <0.001), and PT (

= 0.44;

SE= 0.08;

p <0.001) relative to patients without a significant other. Compared to patients with private insurance, patients with Medicare insurance were significantly and negatively associated with the log odds of community discharge for patients who received OT (

= -0.42;

SE= 0.12;

p <0.001), and PT (

= -0.39;

SE= 0.12;

p <0.001). In comparison to patients with mild TBI, patients with severe TBI were significantly and negatively associated with the log odds of community discharge for patients who received OT (

= -0.83;

SE= 0.31;

p <0.001), and PT (

= -0.68;

SE= 0.29;

p-value=0.02). Comorbidity burden score was significantly and negatively associated with the log odds of community discharge for patients who received OT (

= -0.08;

SE= 0.002;

p <0.001), and PT (

= -0.10;

SE= 0.02;

p <0.001). Longer lengths of stay in acute care was significantly and negatively associated with the log odds of discharge to the community for patients who received OT and PT (

= -0.15;

SE= 0.01;

p <0.001). There was not sufficient evidence to suggest that the other covariates (i.e., sex, and residence location) were significantly associated with community discharge (

p-values= 0.11 – 0.74).

Table 2 presents the coefficient estimates from the logistic regression analysis.

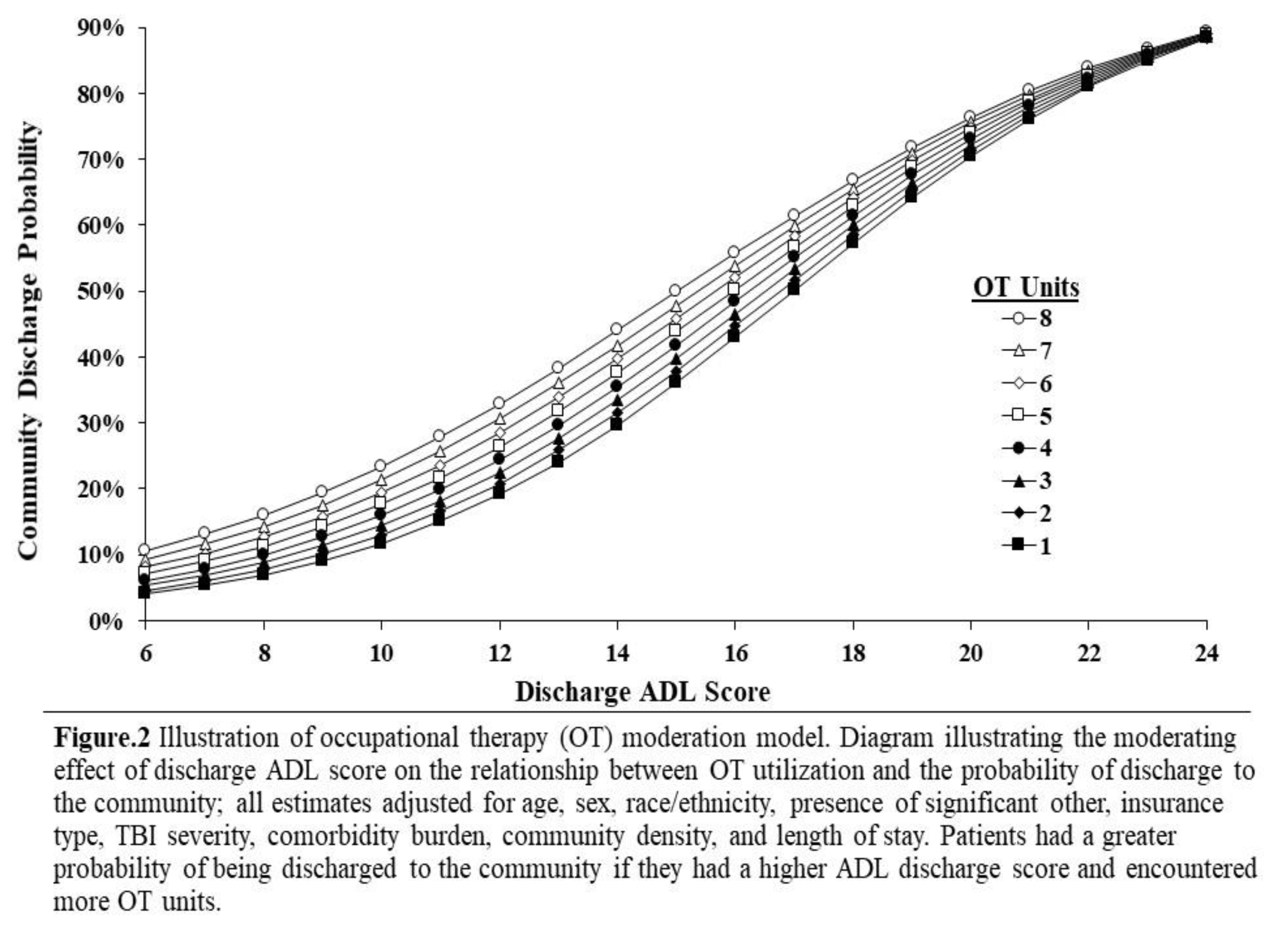

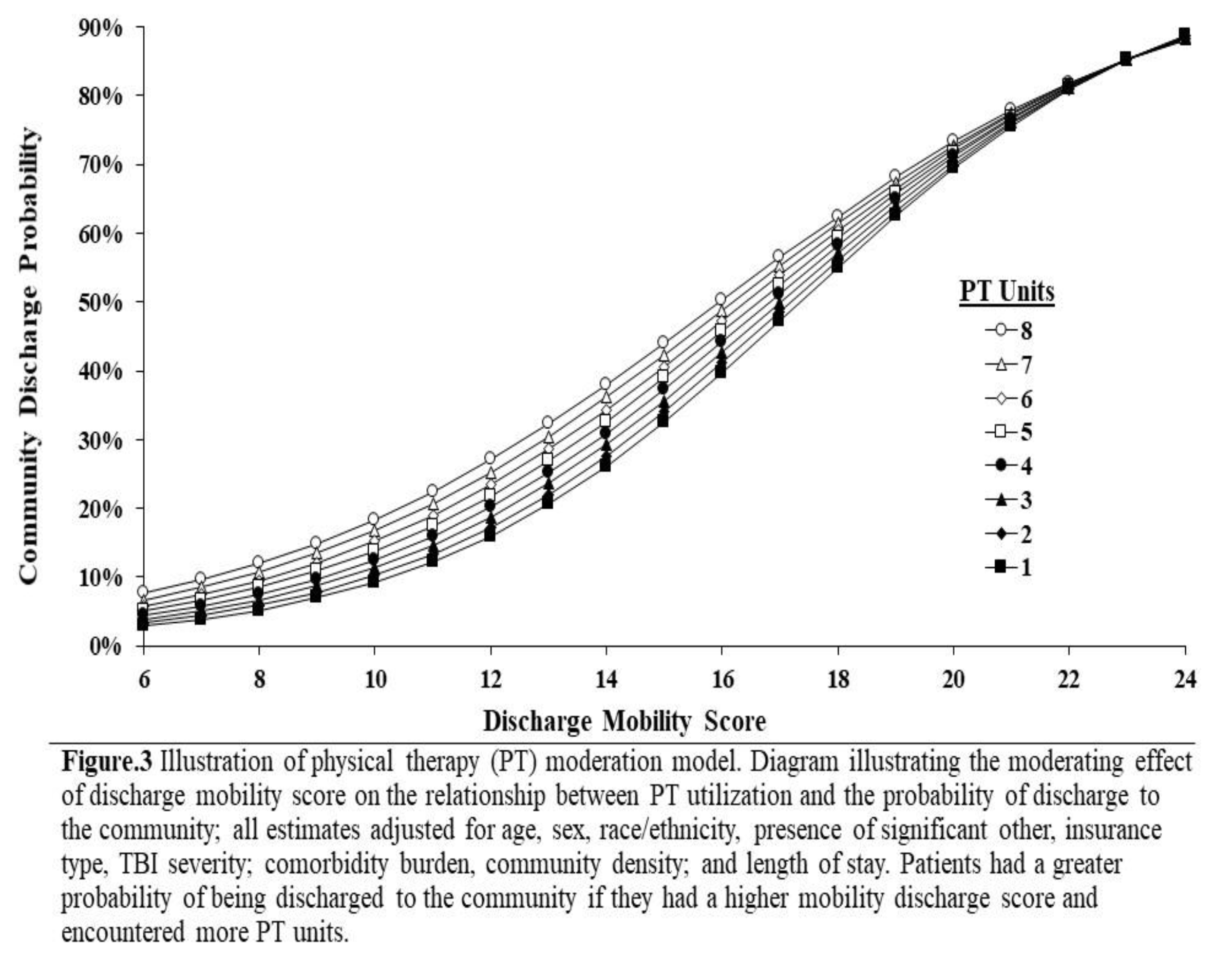

The moderating effect of those variables on the relationship between OT and PT utilization and community discharge was negative and statistically significant (ORs= 0.99, 95% CIs [0.98, 1.00]). This indicates that the magnitude of the OT and PT utilization effect diminished as ADL and mobility scores increased. The main effect of OT and PT utilization was significantly positively associated with community discharge: (OR= 1.21, 95% CI [1.11, 1.33]); (OR=1.22, 95% CI [1.14, 1.30]), respectively (

Table 3). Specifically, patients with

greater OT/PT utilization were 1.21 to 1.22 times more likely to be discharged to the community. The main effect of functional performance (ADL) and physical performance (mobility) scores at discharge demonstrated statistically significant positive associations with community discharge: (OR= 1.34, 95% CI [1.30, 1.39]); (OR=1.38, 95% CI [1.33, 1.42]), respectively. This means that patients with

higher ADL and mobility performance scores at discharge were 1.34 to 1.38 times more likely to be discharged to the community.

Several covariates were significantly associated with community discharge. White individuals demonstrated statistically significant negative associations with community discharge relative to their Hispanic and Black counterparts in both models (OT model White vs. Hispanic (OR= 0.67, 95% CI [0.53, 0.87]), White vs. Black (OR=0.59, 95% CI [0.41, 0.86]); PT model White vs. Hispanic (OR= 0.76, 95% CI [0.61, 0.98]), White vs. Black (OR=0.62, 95% CI [0.43, 0.90]). This implies that non-Hispanic White patients were 0.67 to 0.76 times less likely to be discharged to the community compared to their Hispanic counterparts in both OT and PT models. Similarly, non-Hispanic White patients 0.59 to 0.62 times less likely to be discharged to the community compared to their Black counterparts in both OT and PT models. Age demonstrated statistically significant associations with community discharge (ORs=0.98, 95% CIs [0.97, 0.99]) in both OT and PT models. Specifically, for each one-year increase in age, older patients were 0.98 times less likely to be discharged to the community relative to younger patients. Compared to patients with significant others, patients with no significant other were less likely to experience community discharge (OR=0.62, 95% CI [0.53, 0.74]); (OR=0.64, 95% CI [0.55, 0.76]), for OT and PT models, respectively. Specifically, individuals without a significant other were 0.62 to 0.64 times less likely to experience community discharge. Using patients with Medicare insurance as the reference group, patients with private insurance were 1.48 to 1.53 times more likely to be discharged to the community (OT: OR= 1.53, 95% CI [1.20, 1.95]); (PT: OR= 1.48, 95% CI [1.20, 1.95]). Using severe or moderate TBIs as reference categories, patients with mild TBI were 1.26 to 2.28 times more likely to be discharged to the community (OT model: Mild vs. moderate TBI OR= 1.26, 95% CI [1.00, 1.58]); Mild vs. Severe TBI OR= 2.28, 95% CI [1.23, 4.23]), PT model: Mild vs. moderate TBI OR= 1.30, 95% CI [1.03, 1.63]); Mild vs. Severe TBI OR= 1.97, 95% CI [1.11, 3.50]). Length of stay was associated with community discharge in both OT and PT models (ORs = 0.86, 95% CIs [0.84, 0.88]). Particularly, patients with longer lengths of stay were 0.86 times less likely to be discharged to the community relative to patients with shorter lengths of stay. Patients with greater comorbidity burden (i.e., functional comorbidity index [FX-TBI-CI] scores) were 0.91 to 0.93 times less likely to be discharged to the community (OR= 0.93, 95% CI [0.90, 0.96]) in OT model and (OR=0.91, 95% CI [0.88, 0.94]) in PT model. On the other hand, sex, and community density variables did not show significant associations with community discharge in either model (

p-values= 0.11 – 0. 0.69). See

Table 3. Refer to

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 for illustrations of the moderation models.

Discussion

This study represents the first investigation on whether ADL and mobility performance scores at discharge moderate the relationships between acute care OT and PT utilization and community discharge among adults with TBI. Greater OT and PT utilization was associated with 1.21 to 1.22 times increased odds of being discharged to the community, respectively. Additionally, a higher ADL and mobility performance score at discharge was independently associated with 1.34 to 1.38 times greater odds of community discharge, respectively. Subsequently, the small, but statistically significant negative interaction terms in both models indicated that the magnitude of the OT and PT utilization effect diminished as ADL and mobility scores increased (ORs= 0.99, 95% CIs 0.98, 1.00]). Results may inform efforts to enhance the type or amount of acute care OT or PT services delivered to individuals with TBI to maximize safe community discharge. Results will also offer valuable insights for future research, particularly in exploring the interaction between the amount of acute care OT and PT services utilization, discharge ADL and mobility performance, and their impact on community discharge.

Our findings support our hypothesis that greater OT or PT utilization would be more likely to have a community discharge and that this relationship would differ depending on patients’ functional or physical performances at discharge. Our results are consistent with previous research indicating that greater OT and PT utilization is associated with an increased likelihood of community discharge (O'Brien & Zhang, 2018; Roberts et al., 2016; Thorpe et al., 2018). Our findings align with prior studies reporting that a higher ADL and mobility performance score at discharge is associated with an increased likelihood of community discharge (Horn et al., 2015; Oyesanya, 2020). However, we also found that the relationship between service utilization and discharge setting varies across discharge ADL and mobility scores. Meaning that the magnitude of the OT and PT utilization effect diminished as ADL and mobility scores increased. In our study, the observed negative statistically significant influence of ADL and mobility scores at discharge between rehabilitation services utilization and community discharge may be attributed to patients' cognitive, affective, or behavioral sequalae of TBI, which are often more disabling than objective ADL and physical performance limitations (Howlett, Nelson, & Stein, 2022). In our sample, patients with TBI may show a high ADL and mobility performance score at discharge while exhibiting some personality changes such as impulsivity, irritability, or apathy. Thus, patients with high ADL and mobility scores may require an institutional discharge to address impairments not measured by the ‘6-Clicks’ Basic Mobility or Daily Activity short forms. There is a ‘6-Clicks’ Applied Cognitive Short Form, however, that data was not yet entered into EHR data. Future research should investigate the relationship between acute care OT and PT utilization and community discharge, while accounting for patients’ cognitive abilities, to better address individuals with TBI prognosis following an acute care setting.

Our findings showed that non-Hispanic White patients with TBI were less likely to be discharged to the community relative to both Hispanic and Black patients (OT model White vs. Hispanic (OR= 0.67, 95% CI [0.53, 0.87]), White vs. Black (OR=0.59, 95% CI [0.41, 0.86]); PT model White vs. Hispanic (OR= 0.76, 95% CI [0.61, 0.98]), White vs. Black (OR=0.62, 95% CI [0.43, 0.90]). This finding is consistent with prior research indicating that non-Hispanic White patients were more likely to experience an institutional discharge (e.g., inpatient rehabilitation facilities) compared to non-ethnic minority patients (Cassinat, Nygaard, Hoggard, & Hoffmann, 2024; Meagher, Beadles, Doorey, & Charles, 2015). The effect of ethnic minority status on community discharge may be due to socioeconomic barriers (e.g., lack of health insurance, lack of transportation, or geographic region) (Bowman, Martin, Sharar, & Zimmerman, 2007; Jacobs, Chen, Karliner, Agger-Gupta, & Mutha, 2006). Thus, future research should investigate the impact of ethnic minority status on discharge disposition to better understand how could we support the implementation of the health equity framework in acute care.

Our findings revealed a negative association between a patient's age and their likelihood of community discharge (ORs=0.98, 95% CIs [0.97, 0.99]). This finding aligns with previous studies indicating that increased age was associated with institutional discharge in patients with TBI (Zarshenas et al., 2019). Older patients in our sample may represent patients with serious premorbid conditions who have demonstrated poor functional/physical outcomes at the time of discharge (Pritchard et al., 2020). As a result, these patients may require further inpatient services to continue improving their independence in everyday activities and mobility prior to discharge to the community. In our study, older patients may have not fully recovered during their acute care stay, making institutional discharge the most medically appropriate plan. Also, in our study, older patients may represent patients whose prior living situation was not in the community. More studies on the influence of age on discharge destination are necessary to understand potential disparities in post-acute discharge disposition while accounting for prior living status.

Our findings emphasized a significant association between the presence of a significant other and the likelihood of community discharge. Compared to patients with significant others, patients with no significant other were less likely to experience community discharge: (OR=0.62, 95% CI [0.53, 0.74]); (OR=0.64, 95% CI [0.55, 0.76]), for OT and PT models, respectively. This finding aligns with previous studies indicating that patients who have caregivers were more likely to be discharged home (Rodakowski et al., 2017). The influence of having a significant other on discharge disposition could be related to patients’ goals and preferences for post-acute care and treatment (HHS, 2019). More research is needed to accurately describe the effect of significant other status on healthcare utilization across settings and discharge disposition.

Using patients with Medicaid insurance as the reference group, we observed that patients with private insurance had lower odds of being discharged to the community following PT (OR= 0.76, 95% CI [0.59, 0.97]). This finding aligns with a recent study indicating that patients with public insurance were more likely to discharge to the community relative to patients with private insurance (Sorensen et al., 2020). The influence of insurance type on discharge disposition could be related to patients’ socioeconomic status which impacts discharge disposition (Saposnik et al., 2008). Hence, future studies are warranted to explore the impact of financial barriers, including insurance types and coverages, on safe discharge planning across various settings and systems.

Our findings elucidated significant differences in community discharge based on TBI severity and comorbidity burdens. Our results indicated that compared to patients with severe TBI and greater comorbidity burdens, patients with mild TBI and lower comorbidity burdens were substantially more likely to discharge to the community ((OT model: Mild vs. Severe TBI OR= 2.28, 95% CI [1.23, 4.23]); (comorbidity burden OR= 0.93, 95% CI [0.90, 0.96])); ((PT model: Mild vs. Severe TBI OR= 1.97, 95% CI [1.11, 3.50]); (comorbidity burden OR=0.91, 95% CI [0.88, 0.94])). These findings are consistent with prior research indicating that patients with greater TBI injury severity and comorbidity burden were less likely to be discharged to the community relative to patients with lesser TBI injury severity and comorbidity burden (Lu et al., 2022; Sastry et al., 2022). In our sample, patients with TBI who have a greater comorbidity burden may be more likely to have medical complications such as paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity that may pose a barrier to safe community discharge (Deshpande et al., 2017; Mathew, Deepika, Shukla, Devi, & Ramesh, 2016; Mez et al., 2017). Future research should examine the influence of TBI severity level and comorbidity burden on community discharge across different medical settings.

Our study revealed a significant negative relationship between length of stay in acute care and the likelihood of community discharge (ORs = 0.86, 95% CIs [0.84, 0.88]). This finding aligns with previous literature indicating that patients with longer lengths of stay were less likely to be discharged to the community relative to patients with shorter stays (T. O. Oyesanya, 2020; Tolu O. Oyesanya et al., 2021). The influence of length of stay on discharge disposition could be related to patients’ functional and physical status, impacting community discharge. Patients with longer lengths of stay may have greater medical complications that may pose a barrier to community discharge (Deshpande et al., 2017; Mez et al., 2017). Thus, future studies should examine the influence of patients’ lengths of stay and accompanied medical complications on the likelihood of community discharge.

Study Limitations

This study is subject to a few limitations. Firstly, the reliance on EHR data introduces the possibility of missing information, misclassifications, and coding and reporting errors. Additionally, our investigation was confined to 14 hospitals within a single large health system, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other health systems. It is crucial for future research to replicate our findings in diverse health systems to assess the applicability of our results to geographically varied patients with TBI. Our dataset had no information about prior living situation; thus, future research should explore the influence of patients’ prior living situation on discharge location. Additionally, we did not include cognitive assessment data in our analyses. Standardized cognitive assessments are often not administered to all patients in acute care settings or are not recorded in standard electronic flow sheets. Future studies should examine the influence of patients’ cognitive status, if available, on patients’ discharge disposition. Our dataset also had no information about prior functional status or home health OT/PT. Future research should explore the influence of patients’ prior functional status, and home health OT/PT on discharge ADL/mobility score and specific discharge location. Our study did not examine specific discharge destinations, such as Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility (IRF) versus skilled nursing facility; instead, discharge disposition was categorized broadly into community versus institutional. Future research should explore the association between OT/PT utilization and specific discharge destinations to provide a more detailed understanding of the determinants of discharge location among patients hospitalized with TBI in acute care settings.

Conclusion

We examined whether ADL and mobility performance score at discharge moderated the relationship between acute care OT and PT utilization and discharge to the community among adults with TBI. Both ADL and mobility performance scores at discharge moderated the relationship between OT and PT utilization and community discharge. Higher OT and PT utilization was associated with increased odds of being discharged to the community and higher ADL and mobility performance score at discharge was independently associated with greater odds of community discharge. The observed positive statistically significant effects of OT and PT utilization simply decreased with increasing discharge ADL and mobility scores. Further research is warranted to determine the generalizability of our findings, evaluate the impact of patients’ prior health and cognitive status, and other sociodemographic factors (e.g., age, ethnicity, insurance type, and significant other status) on the relationship between OT and PT utilization and community discharge. Findings of this study can inform occupational and physical therapists’ efforts aimed at enhancing the type or amount of acute care OT and PT services delivered to individuals with TBI to maximize safe community discharge.

Appendix A

STROBE Statement—Checklist of items that should be included in reports of

cross-sectional studies

| |

Item No |

Recommendation |

| Title and abstract |

1 |

(a) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract |

| (b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found |

| Introduction |

| Background/rationale |

2 |

Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported |

| Objectives |

3 |

State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses |

| Methods |

| Study design |

4 |

Present key elements of study design early in the paper |

| Setting |

5 |

Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection |

| Participants |

6 |

(a) Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants |

| Variables |

7 |

Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable |

| Data sources/ measurement |

8* |

For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group |

| Bias |

9 |

Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias |

| Study size |

10 |

Explain how the study size was arrived at |

| Quantitative variables |

11 |

Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why |

| Statistical methods |

12 |

(a) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding |

| (b) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions |

| (c) Explain how missing data were addressed |

| (d) If applicable, describe analytical methods taking account of sampling strategy |

| (e) Describe any sensitivity analyses |

| Results |

| Participants |

13* |

(a) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study—eg numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analysed |

| (b) Give reasons for non-participation at each stage |

| (c) Consider use of a flow diagram |

| Descriptive data |

14* |

(a) Give characteristics of study participants (eg demographic, clinical, social) and information on exposures and potential confounders |

| (b) Indicate number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest |

| Outcome data |

15* |

Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures |

| Main results |

16 |

(a) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (eg, 95% confidence interval). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included |

| (b) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized |

| (c) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period |

| Other analyses |

17 |

Report other analyses done—eg analyses of subgroups and interactions, and sensitivity analyses |

| Discussion |

| Key results |

18 |

Summarise key results with reference to study objectives |

| Limitations |

19 |

Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias |

| Interpretation |

20 |

Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence |

| Generalisability |

21 |

Discuss the generalisability (external validity) of the study results |

| Other information |

| Funding |

22 |

Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based |

| * Give information separately for exposed and unexposed groups. Note: An Explanation and Elaboration article discusses each checklist item and gives methodological background and published examples of transparent reporting. The STROBE checklist is best used in conjunction with this article (freely available on the Web sites of PLoS Medicine at http://www.plosmedicine.org/, Annals of Internal Medicine at http://www.annals.org/, and Epidemiology at http://www.epidem.com/). Information on the STROBE Initiative is available at www.strobe-statement.org. |

| Counting minutes for service units |

| Number of service units |

Number of minutes |

| 1 |

(≥ 8 minutes through 22 minutes) |

| 2 |

(≥ 23 minutes through 37 minutes) |

| 3 |

(≥ 38 minutes through 52 minutes) |

| 4 |

(≥ 53 minutes through 67 minutes) |

| 5 |

(≥ 68 minutes through 82 minutes) |

| 6 |

(≥ 83 minutes through 97 minutes) |

| 7 |

(≥ 98 minutes through 112 minutes) |

| 8 |

(≥ 113 minutes through 127 minutes) |

| Reference: Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing (HCPF). (2023, July 7) Billing manuals. Retrieved November 13, 2023, from https://hcpf.colorado.gov/ptot-manual#units. |

References

- Arya, S., Langston, A. H., Chen, R., Sasnal, M., George, E. L., Kashikar, A., . . . Morris, A. M. (2022). Perspectives on Home Time and Its Association With Quality of Life After Inpatient Surgery Among US Veterans. JAMA Network Open, 5(1), e2140196-e2140196. [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S. M., Martin, D. P., Sharar, S. R., & Zimmerman, F. J. (2007). Racial Disparities in Outcomes of Persons with Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Medical Care, 45(7), 686-690. [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. W., Lee, M., Lennon, R. J., & Niewczyk, P. M. (2020). Functional Performance and Discharge Setting Predict Outcomes 3 Months After Rehabilitation Hospitalization for Stroke. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases, 29(5), 104746. [CrossRef]

- Cassinat, J., Nygaard, J., Hoggard, C., & Hoffmann, M. (2024). Predictors of mortality and rehabilitation location in adults with prolonged coma following traumatic brain injury. PM & R. [CrossRef]

- Chevalley, O., Truijen, S., Saeys, W., & Opsommer, E. (2022). Socio-environmental predictive factors for discharge destination after inpatient rehabilitation in patients with stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Disability and rehabilitation, 44(18), 4974-4985. [CrossRef]

- Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, D. (2015). <TBI Severity Classifications. DoD Worldwide Numbers for TBI>.

- Deshpande, S. K., Hasegawa, R. B., Rabinowitz, A. R., Whyte, J., Roan, C. L., Tabatabaei, A., . . . Small, D. S. (2017). Association of Playing High School Football With Cognition and Mental Health Later in Life. JAMA neurology, 74(8), 909-918. [CrossRef]

- Ejlersen Wæhrens, E., & Fisher, A. G. (2007). Improving quality of ADL performance after rehabilitation among people with acquired brain injury. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy, 14(4), 250-257. [CrossRef]

- Horn, S. D. P., Corrigan, J. D. P., Beaulieu, C. L. P., Bogner, J. P., Barrett, R. S. M. S., Giuffrida, C. G. P. O. T. R. L. F., . . . Deutscher, D. P. T. P. (2015). Traumatic Brain Injury Patient, Injury, Therapy, and Ancillary Treatments Associated With Outcomes at Discharge and 9 Months Postdischarge. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 96(8), S304-S329. [CrossRef]

- Howlett, J. R., Nelson, L. D., & Stein, M. B. (2022). Mental Health Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury. Biological psychiatry (1969), 91(5), 413-420. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, E., Chen, A. H., Karliner, L. S., Agger-Gupta, N., & Mutha, S. (2006). The Need for More Research on Language Barriers in Health Care: A Proposed Research Agenda. The Milbank quarterly, 84(1), 111-133. [CrossRef]

- Jette, D. U., Grover, L., & Keck, C. P. (2003). A Qualitative Study of Clinical Decision Making in Recommending Discharge Placement From the Acute Care Setting. Physical Therapy, 83(3), 224-236. [CrossRef]

- Jette, D. U., Stilphen, M., Ranganathan, V. K., Passek, S. D., Frost, F. S., & Jette, A. M. (2014). AM-PAC “6-Clicks” Functional Assessment Scores Predict Acute Care Hospital Discharge Destination. Physical Therapy, 94(9), 1252-1261. [CrossRef]

- Kanchan, A., Singh, A., Khan, N., Jahan, M., Raman, R., & Sathyanarayana Rao, T. (2018). Impact of neuropsychological rehabilitation on activities of daily living and community reintegration of patients with traumatic brain injury. Indian journal of psychiatry, 60(1), 38-48. [CrossRef]

- Klima, D., Morgan, L., Baylor, M., Reilly, C., Gladmon, D., & Davey, A. (2019). Physical Performance and Fall Risk in Persons With Traumatic Brain Injury. Percept Mot Skills, 126(1), 50-69. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. G., Zhong, X., Whiteneck, G. G., Mazumdar, M., Hammond, F. M., Egorova, N., . . . Dams-O'Connor, K. (2022). Development and Validation of a Functionally Relevant Comorbid Health Index in Adults Admitted to Inpatient Rehabilitation for Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of neurotrauma, 39(1-2), 67-75. [CrossRef]

- Lo, J., Chan, L., & Flynn, S. (2021). A Systematic Review of the Incidence, Prevalence, Costs, and Activity and Work Limitations of Amputation, Osteoarthritis, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Back Pain, Multiple Sclerosis, Spinal Cord Injury, Stroke, and Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: A 2019 Update. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 102(1), 115-131. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J., Gormley, M., Donaldson, A., Agyemang, A., Karmarkar, A., & Seel, R. T. (2022). Identifying factors associated with acute hospital discharge dispositions in patients with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 36(3), 383-392. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, M. J., Deepika, A., Shukla, D., Devi, B. I., & Ramesh, V. J. (2016). Paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity in severe traumatic brain injury. Acta neurochirurgica, 158(11), 2047-2052. [CrossRef]

- Meagher, A. D., Beadles, C. A., Doorey, J., & Charles, A. G. (2015). Racial and ethnic disparities in discharge to rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg, 122(3), 595-601. [CrossRef]

- Mez, J., Daneshvar, D. H., Kiernan, P. T., Abdolmohammadi, B., Alvarez, V. E., Huber, B. R., . . . McKee, A. C. (2017). Clinicopathological Evaluation of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Players of American Football. JAMA, 318(4), 360-370. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, S. R., & Zhang, N. (2018). Association Between Therapy Intensity and Discharge Outcomes in Aged Medicare Skilled Nursing Facilities Admissions. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 99(1), 107-115. [CrossRef]

- Olsson, A., Berglöv, A., & Sjölund, B.-M. (2020). “Longing to be independent again” – A qualitative study on older adults’ experiences of life after hospitalization. Geriatric nursing (New York), 41(6), 942-948. [CrossRef]

- Oyesanya, T. O. (2020). Selection of discharge destination for patients with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj, 34(9), 1222-1228. [CrossRef]

- Oyesanya, T. O., Harris, G., Yang, Q., Byom, L., Cary Jr, M. P., Zhao, A. T., & Bettger, J. P. (2021). Inpatient rehabilitation facility discharge destination among younger adults with traumatic brain injury: differences by race and ethnicity. Brain Injury, 35(6), 661-674. [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, K. T., Hong, I., Goodwin, J. S., Westra, J. R., Kuo, Y.-F., & Ottenbacher, K. J. (2020). Association of Social Behaviors With Community Discharge in Patients with Total Hip and Knee Replacement. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2023). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. : R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/.

- Roberts, P. S., Mix, J., Rupp, K., Younan, C., Mui, W., Riggs, R. V., & Niewczyk, P. (2016). Using Functional Status in the Acute Hospital to Predict Discharge Destination for Stroke Patients. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 95(6), 416-424. [CrossRef]

- Rodakowski, J., Rocco, P. B., Ortiz, M., Folb, B., Schulz, R., Morton, S. C., . . . James, A. E. (2017). Caregiver Integration During Discharge Planning for Older Adults to Reduce Resource Use: A Metaanalysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(8), 1748-1755. [CrossRef]

- Saposnik, G., Jeerakathil, T., Selchen, D., Baibergenova, A., Hachinski, V., & Kapral, M. K. (2008). Socioeconomic Status, Hospital Volume, and Stroke Fatality in Canada. Stroke (1970), 39(12), 3360-3366. [CrossRef]

- Sastry, R. A., Feler, J. R., Shao, B., Ali, R., McNicoll, L., Telfeian, A. E., . . . Gokaslan, Z. L. (2022). Frailty independently predicts unfavorable discharge in non-operative traumatic brain injury: A retrospective single-institution cohort study. PLOS ONE, 17(10), e0275677-e0275677. [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, M., Sercy, E., Salottolo, K., Waxman, M., West, T. A., Tanner, n. A., & Bar-Or, D. (2020). The effect of discharge destination and primary insurance provider on hospital discharge delays among patients with traumatic brain injury: a multicenter study of 1,543 patients. Patient safety in surgery, 14(1), 2-2. [CrossRef]

- Souesme, G., Voyer, M., Gagnon, É., Terreau, P., Fournier-St-Amand, G., Lacroix, N., . . . Ouellet, M.-C. (2022). Barriers and facilitators linked to discharge destination following inpatient rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury in older adults: a qualitative study. Disability and rehabilitation, 44(17), 4738-4749. [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, E. R., Garrett, K. B., Smith, A. M., Reneker, J. C., & Phillips, R. S. (2018). Outcome Measure Scores Predict Discharge Destination in Patients With Acute and Subacute Stroke: A Systematic Review and Series of Meta-analyses. Journal of neurologic physical therapy, 42(1), 2-11. [CrossRef]

- Trevena-Peters, J., McKay, A., Spitz, G., Suda, R., Renison, B., & Ponsford, J. (2018). Efficacy of Activities of Daily Living Retraining During Posttraumatic Amnesia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 99(2), 329-337.e322. [CrossRef]

- van Baalen, B., Odding, E., & Stam, H. J. (2008). Cognitive status at discharge from the hospital determines discharge destination in traumatic brain injury patients. Brain Injury, 22(1), 25-32. [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2014). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. International journal of surgery (London, England), 12(12), 1495-1499. [CrossRef]

- Werner, R. M., Coe, N. B., Qi, M., & Konetzka, R. T. (2019). Patient Outcomes After Hospital Discharge to Home With Home Health Care vs to a Skilled Nursing Facility. JAMA Internal Medicine, 179(5), 617. [CrossRef]

- Whiteneck, G. G., Cuthbert, J. P., Corrigan, J. D., & Bogner, J. A. (2016). Prevalence of Self-Reported Lifetime History of Traumatic Brain Injury and Associated Disability: A Statewide Population-Based Survey. The journal of head trauma rehabilitation, 31(1), E55-E62. [CrossRef]

- Zarshenas, S., Colantonio, A., Alavinia, S. M., Jaglal, S., Tam, L., & Cullen, N. (2019). Predictors of Discharge Destination From Acute Care in Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. The journal of head trauma rehabilitation, 34(1), 52-64. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).