2. Results

Coulometric titration of sulfur- and selenium-containing amino acids was carried out with electrogenerated bromine. Electrooxidation of bromide ions on a platinum electrode in acidic media can lead to the formation of oxidizers - Br

3-, Br

2, as well as short–lived bromine radicals (Br*) adsorbed on the surface of the platinum electrode [

10]. The resulting bromine and bromine-containing compounds easily enter into radical, redox, electrophilic aromatic substitution, and addition reactions [

11]. Coulorimetric titration can be performed in different solvents, pH, to test and compare different antioxidants. Aminoacids have been examined in water solutions, nonpolar selenium-containing xenobiotics – in methanol.

At the beginning, controlled-current coulometry of aminoacids were carried out in aqueous solution at 5.0 mA [

12]. Then to compare the antioxidant properties of selenium- and sulfur-containing substances, bromine was electrogenerated in 85% methanol at 50 mA [

13]. The current has been increased to minimize adverse reactions and the duration of the analysis.

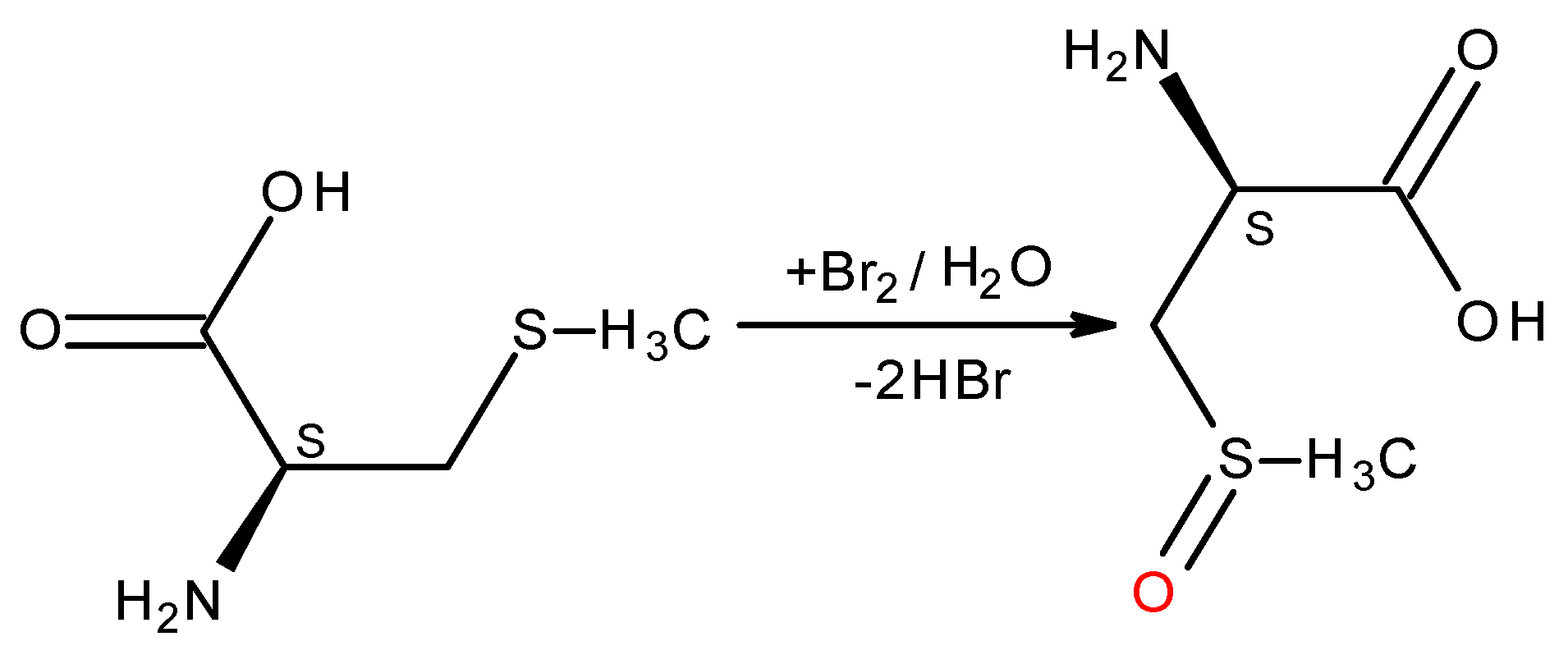

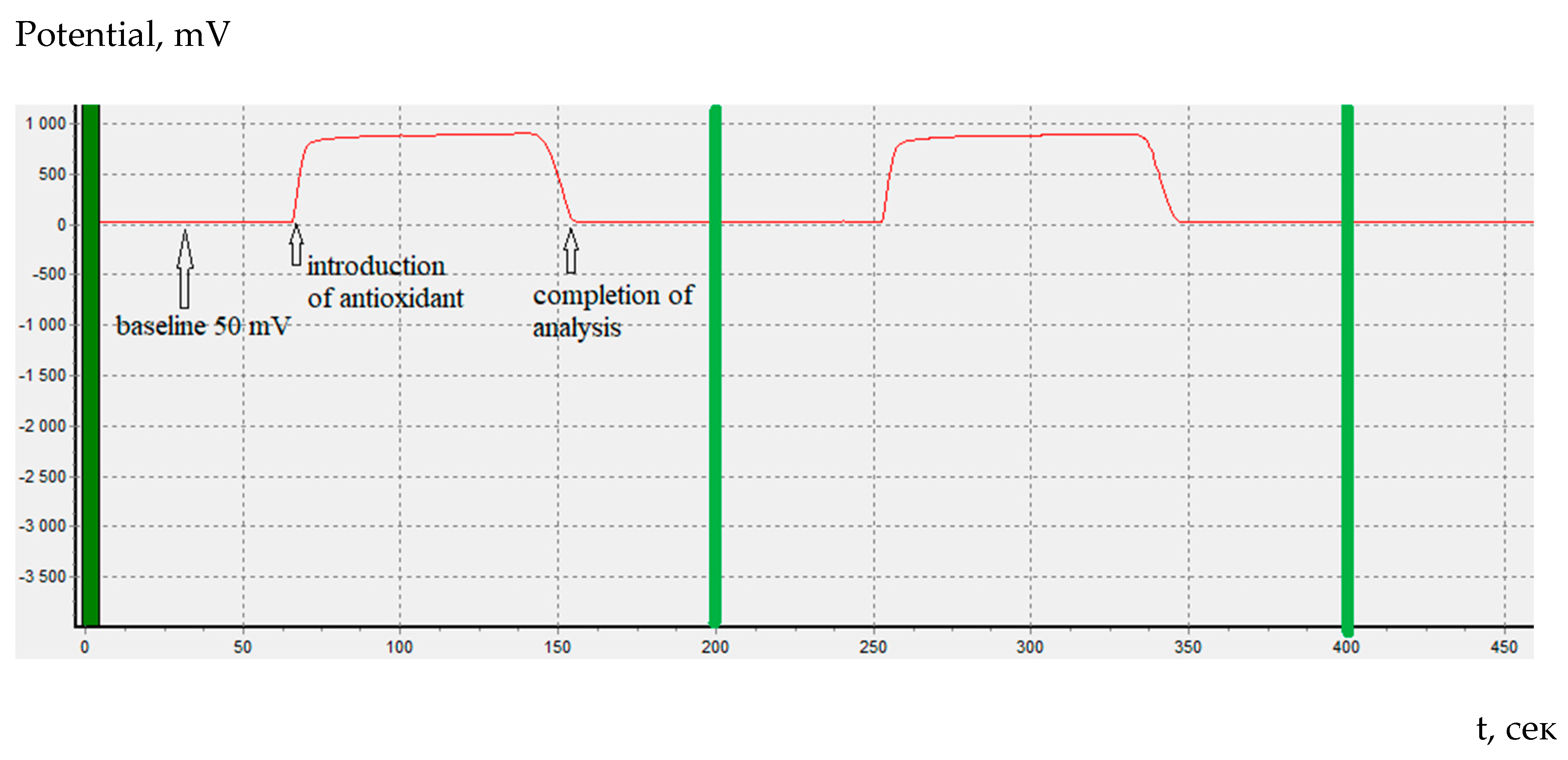

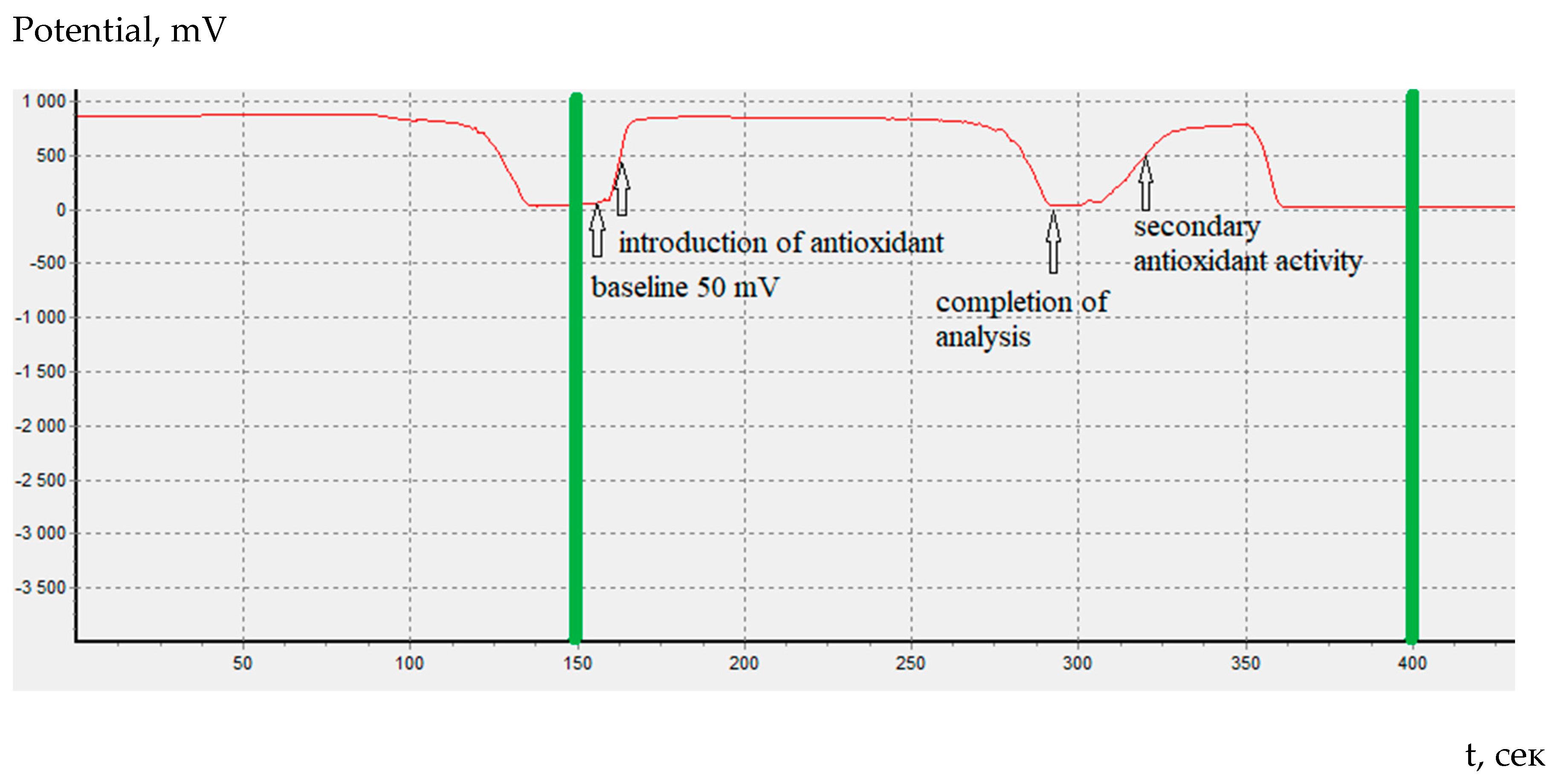

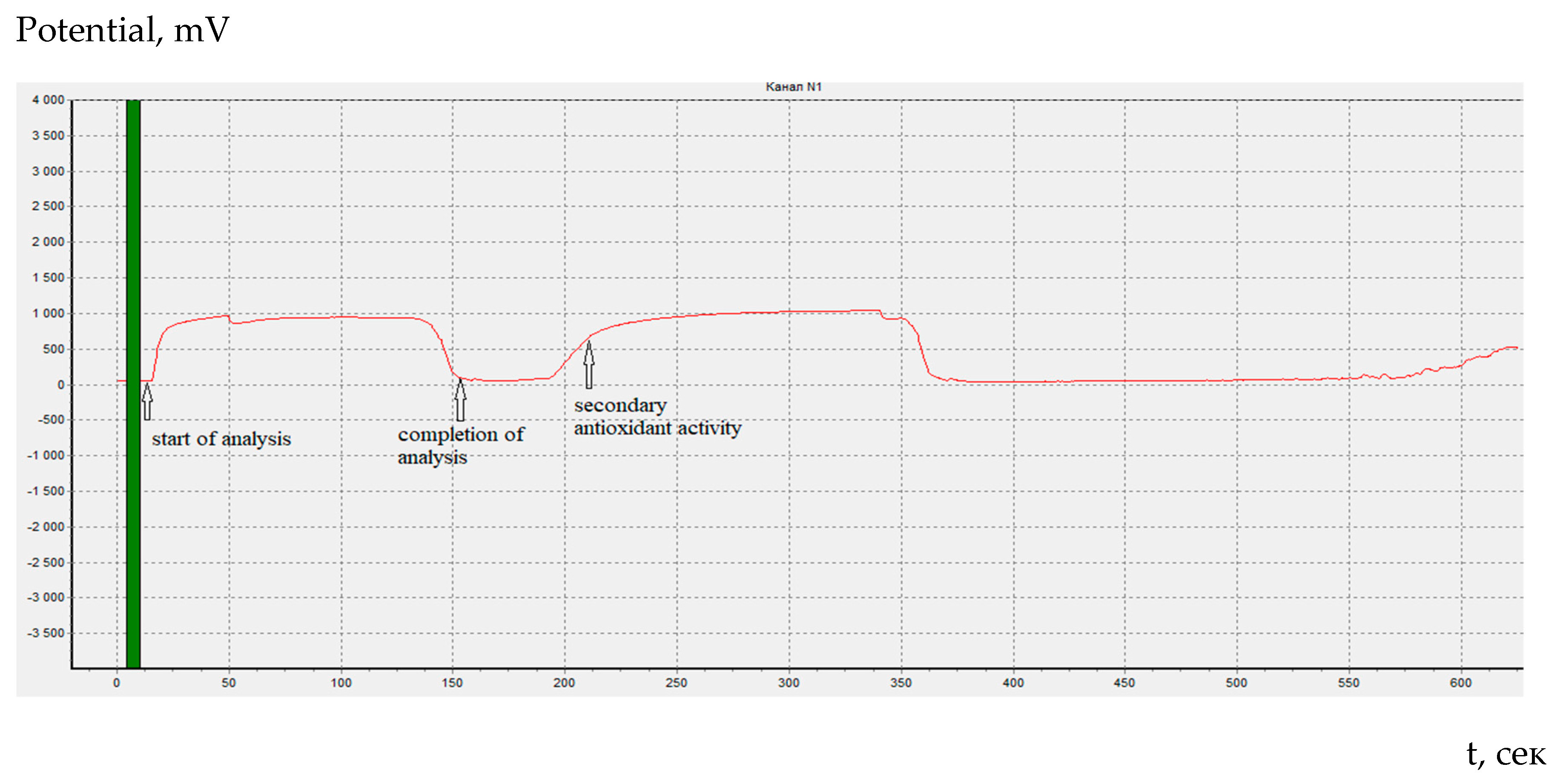

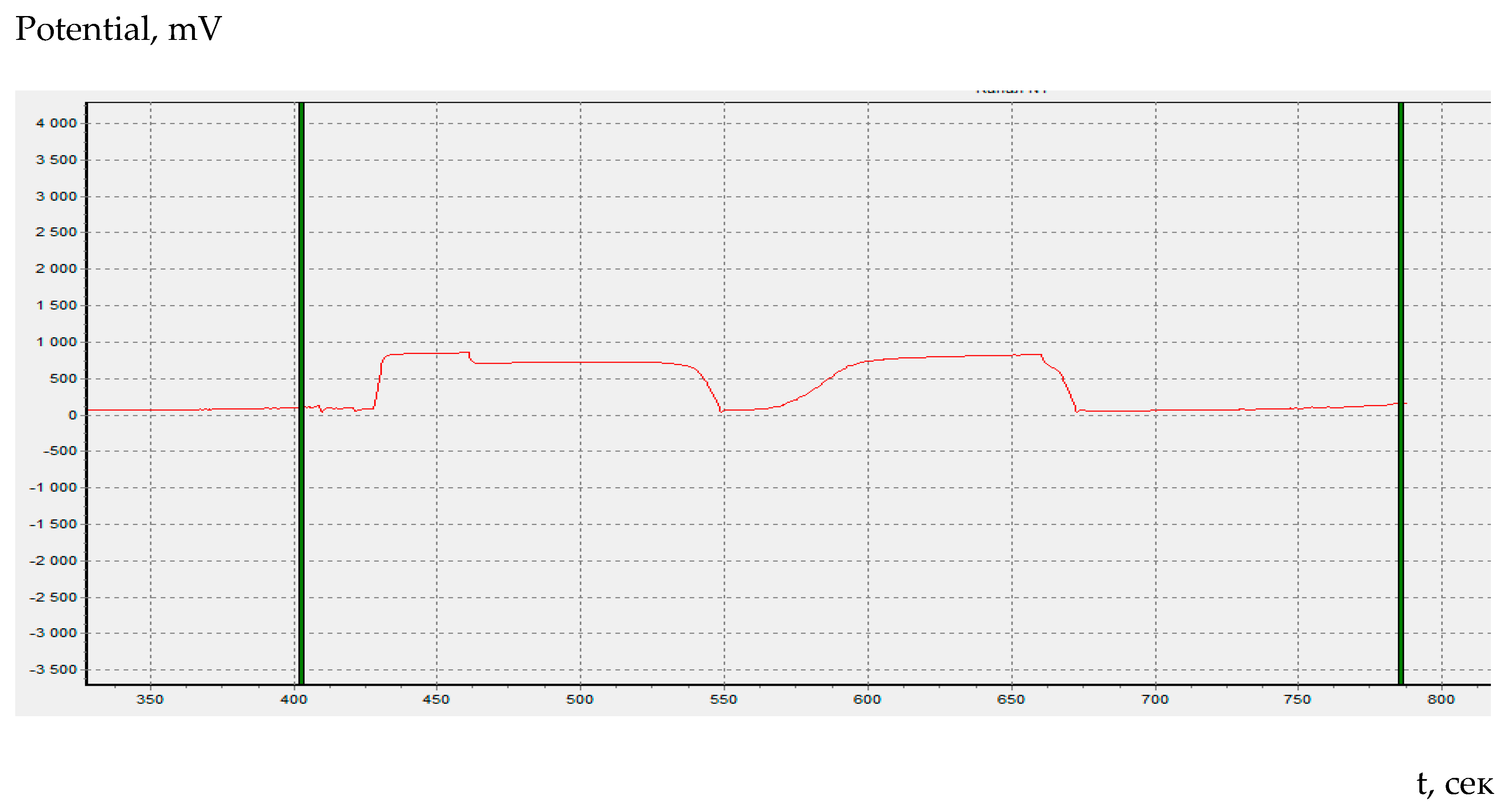

In coulometric titration (controlled-current coulometry) the endpoint indication is effected voltametrically by modulating an alternating current of constant strength to a double Pt electrode. This results in a voltage differential between the Pt wires. This is drastically reduced as the free bromine are present (

Figure 1).

L-Methionine antioxidant capacity. In vivo oxidation of methionine into sulfoxide (Met-O), can regulate protein functions.

L-Methionine can be reduced back by

L-methionine sulfoxide reductases, so the reversible methionine oxidation plays an important role in protecting cells against oxidative stress and damage [

14,

15].

L-Methionine reversible redox cycle have been implicated in regulation of aging process and impacts the lifespan [

16,

17].

Stoichiometric relationship between methionine and electrogenerated halogens (chlorine, bromine and iodine) are known [

18]. Our coulometric titration with bromine was in good agreement with those in the literature, so we used

L-methionine as a reference substance to determine the electrochemical ratios of tested substances. The reaction of

L-methionine with bromine proceeds in a ratio of 1:1 (2 electrons), to give amino acid sulfoxide (

L-methionine sulfone) (

Scheme 1).

We noted a slight less (10-14%) antioxidant capacity of methionine and amino acids, in the methanol electrolyte over in water solutions. This should be a result of possible alternative reactions with bromine in methanol and application of higher current to reduce the analysis time.

L-selenocysteine antioxidant capacity.

L-selenocysteine/selenocystine is the 21st amino acid which forms catalytically active centre of glutathione peroxidases and essential for their activity [

19]. The central functions of glutathione peroxidases are reduction of complex hydroperoxides, balance oxidative homeostasis in cells and protect them from oxidative damage. Electrochemical oxidation of selenocystine in which six electron-transfers were involved, yielded selenocystine selenoxide [

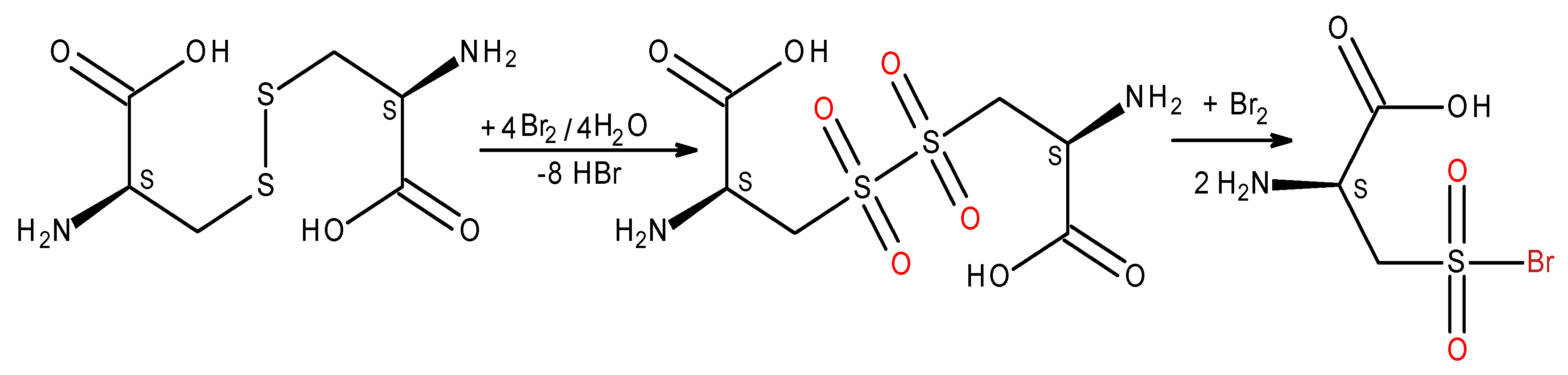

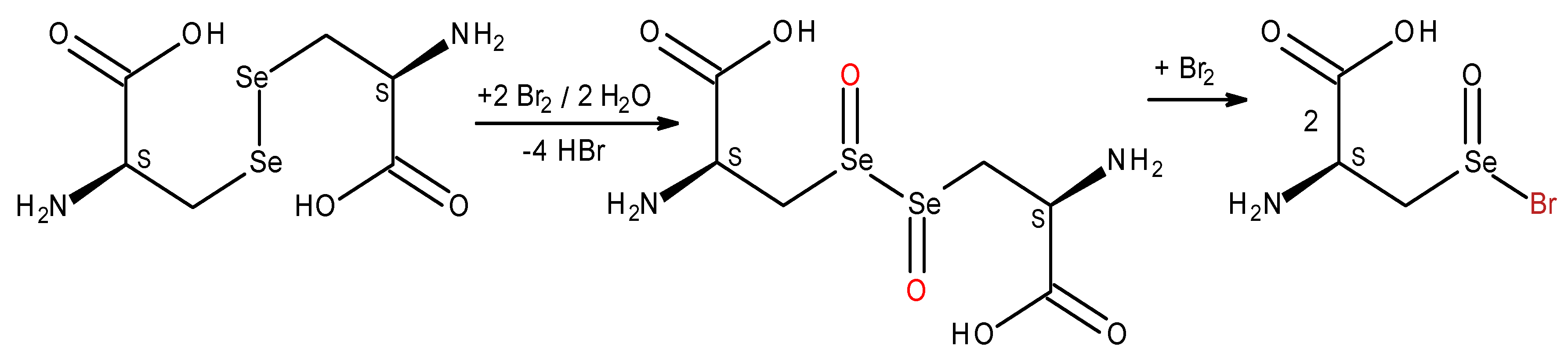

20]. In our experiments

L-Selenocystine reacts with electrogenerated bromine quickly and quantitatively in water and in methanol with the ratio selenocystine-bromine 1:3. The oxidation induces a transfer of six electrons which underlies the formation of 2-amino-3-bromosele ninylpropanoic acid (

Scheme 2,

Figure 1).

L-Cystine antioxidant capacity.

L-Cystine is a protein sulfur-containing amino acid, participates in antioxidant defenses as a free radical scavenger and is involved in cell redox balance [

21,

22,

23].

L-Cysteine is highly susceptible to oxidation, its oxidation occurs in two steps. Under the action of relatively weak oxidizer (iodine) cysteine is oxidized into cystine (dimer), whereas more strong oxidizer (electrogenerated bromine) yields disulfonacystine and 2-amino-3-bromosulfonylpropanoic acid.

The chemistry of

L-cystine oxidation with bromine is consistent with the oxidation of disulfides to sulfoxides or further to sulfones [

24], to form amino acid sulfone and 2-amino-3-bromosulfonylpropanoic acid as a products in the ratio of 1:5 (10 ē).

Scheme 3.

Reaction of electrogenerated bromine with L-cystine.

Scheme 3.

Reaction of electrogenerated bromine with L-cystine.

In our experiments after the endpoint of coulometric titration of cystine we saw an additional change in the Ox/Red potential which can be attributed to a new wave of oxidation. The first step on the cystine coulometry corresponds to oxidation to sulfoxide. At potentials of the second stage, further oxidation of the reaction products probably occurs (

Figure 2).

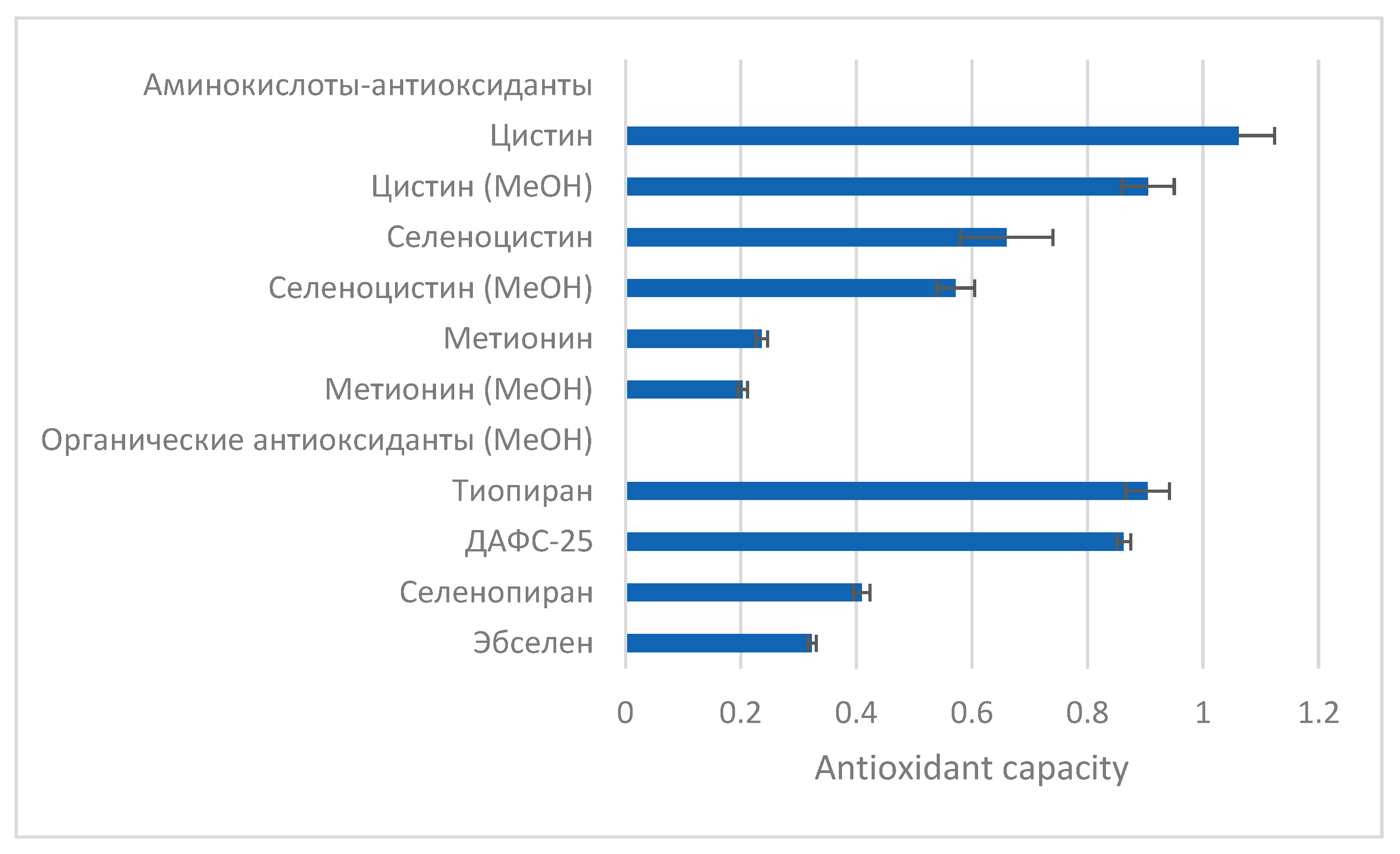

Thus, in water solutions, the antioxidant capacity decreases in the following order:

L-cystine>

L-selenocystine >

L-methionine (

Figure 3).

Among the tested substances the greatest antioxidant capacity was recorded for

L-cystine, its selenium analog

L-selenocystine exhibited particularly lower values. The results are consistent with [

25,

26] where cysteine-sulfinic acid is also easily oxidized to sulfonic acid (Cys-SO

3–), whereas Sec-SeO

2–"resists" further oxidation into selenonic acid (Sec-SeO

3–). Such specific features can be explained by dual-functionalities of selenocystine to act both as anantioxidant and pro-oxidant. Selenium, unlike sulfur, is resistant to over-oxidation and can be reduced easily.

Selenium-containing xenobiotics – ebselen, selenopyran [

27], diacetophenonyl selenide [

28] – are both antioxidants and enzyme mimetics [

29], can activate antioxidant defence in various organisms [

30,

31].

Ebselene antioxidant capacity. Ebselene (2-phenylbenzoselenazole-1,2-3(2h)-oh), a selenium–containing xenobiotic, effectively compensates the decrease in GPX activity and is considered as a potentially pharmacologically active molecule for the treatment of diseases associated with diabetes – atherosclerosis and nephropathy [

32]. At the same time, the selenium in ebselen is not released and thus is not bioavailable [

33]. In the adipose tissues it is present in the form of metabolites, which, under the action of GSH, are easily reduced to the initial ebselene [

34]. Ebselene is oxidized by hydrogen peroxide accompanied by hydrolysis, so the oxidation does not stop at selenoxide, and leads to form selenic acid [

35]. Ebselene exhibits radical-scavenging activity in the radical polymerization of methyl methacrylate, and can act in biological systems as a suppressor of polyunsaturated fatty acid radicals [

36].

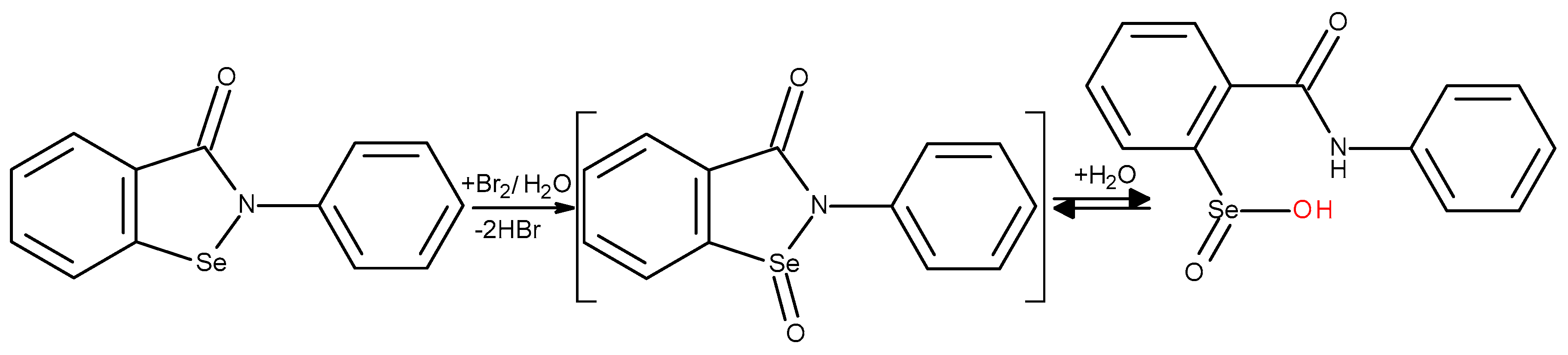

It was found that ebselen in coulometric cell reacts with electrogenerated bromine in a stoichiometric ratio between ebselen and bromine 1:1.6, i.e., induces a transfer of electrons ranging from 2 to 4, which underlies the formation of several alternative oxidation-bromination products (

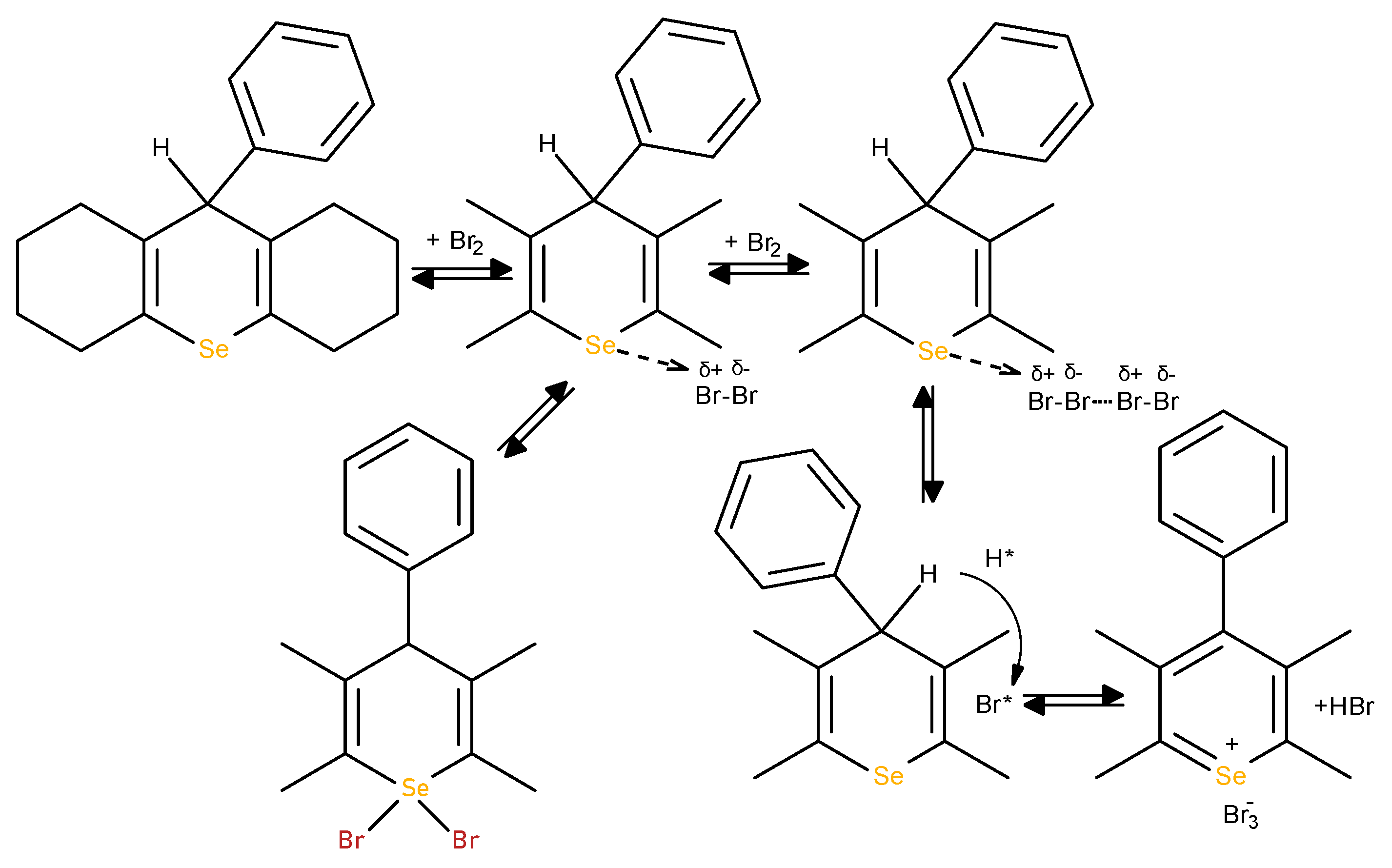

Scheme 4).

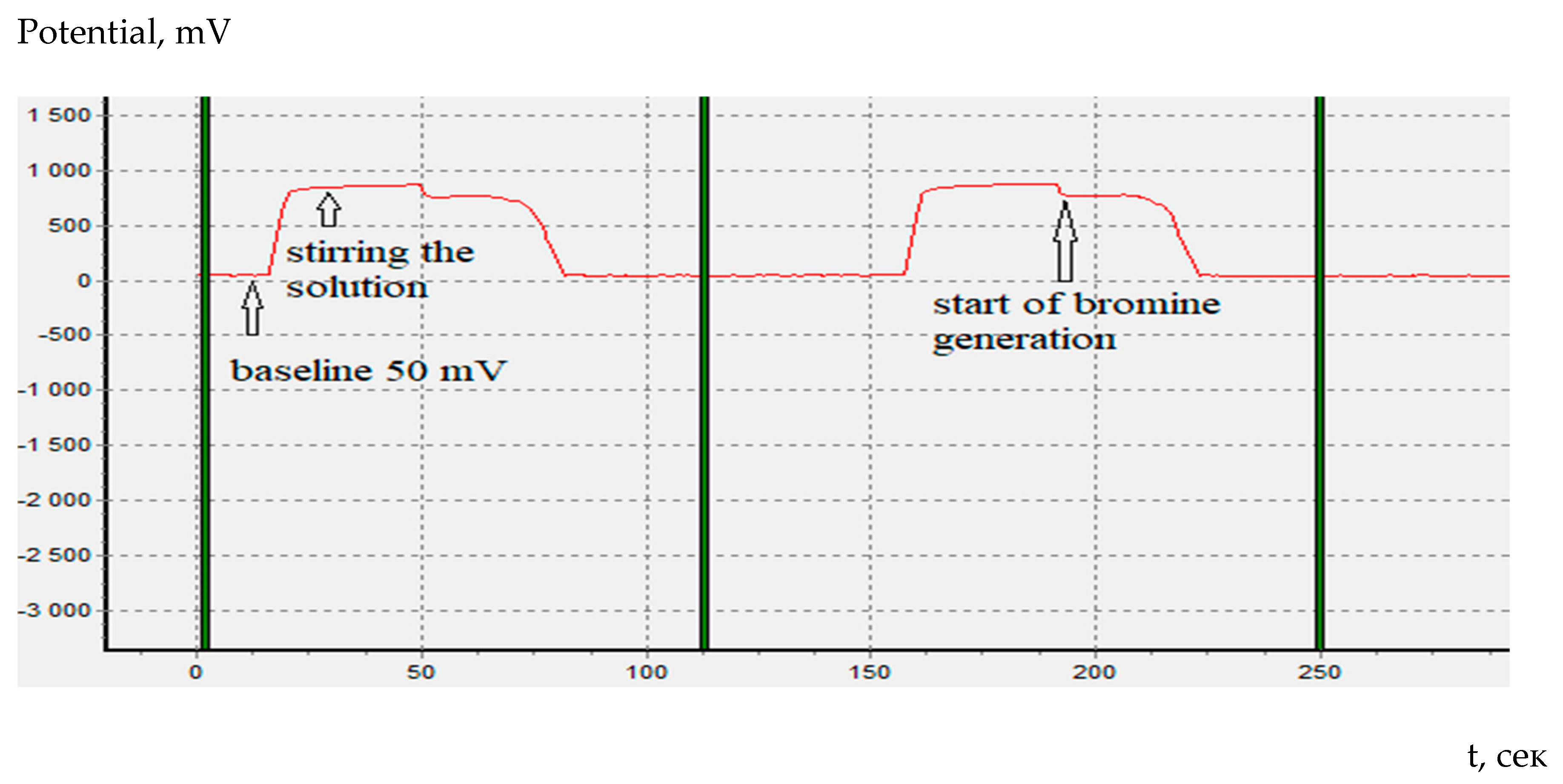

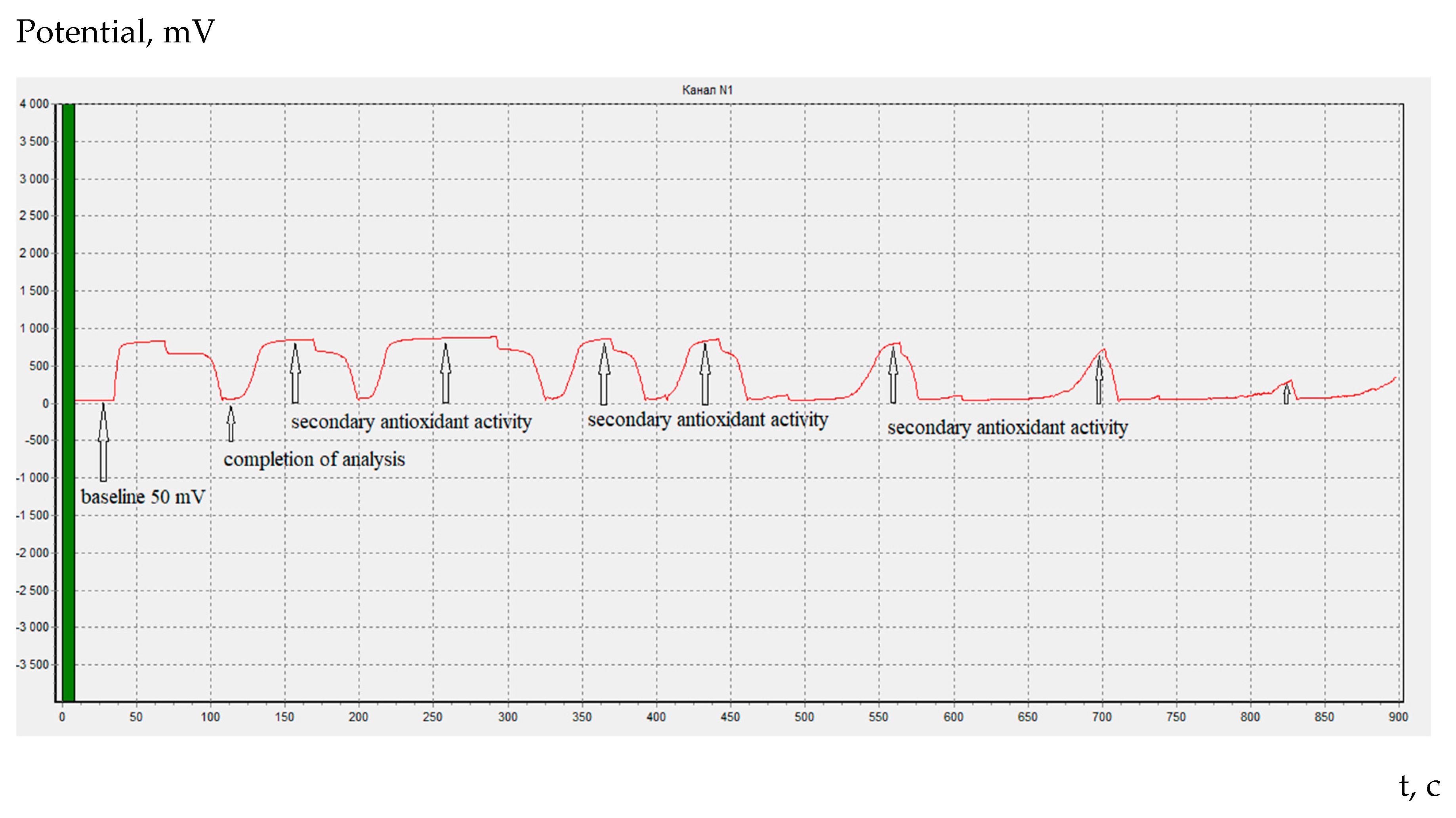

It should be noted that in constant-current coulometry of organic antioxidants, unlike amino acids, it is possible to determine the beginning of bromine generation on the coulometric titration curve (

Figure 4).

Diacetophenonyl selenide (DAPS-25, 1,5-diphenyl-3-selenapentadion-1,5) antioxidant capacity. The direct antioxidant activity of diacetophenonyl selenide was not tested so far, but its possibility to act in vivo as antioxidant enzymes activators and lipid peroxidation protector are discussed [

37]. Zhukov et al investigated reaction of several 3-thio(selenium)pentane-1,5-diones and diacetophenonyl selenide in particular with PCl

5 and found that carbonyl group was not affected. Sulfur-containing 1,5-diketones undergo rearrangement, forming the 2-chlorine derivatives, and their selenium-containing analogues, at any reagents ratios, form a stable 3,3-dichloro-3-selenapentane-1,5-dione [

38].

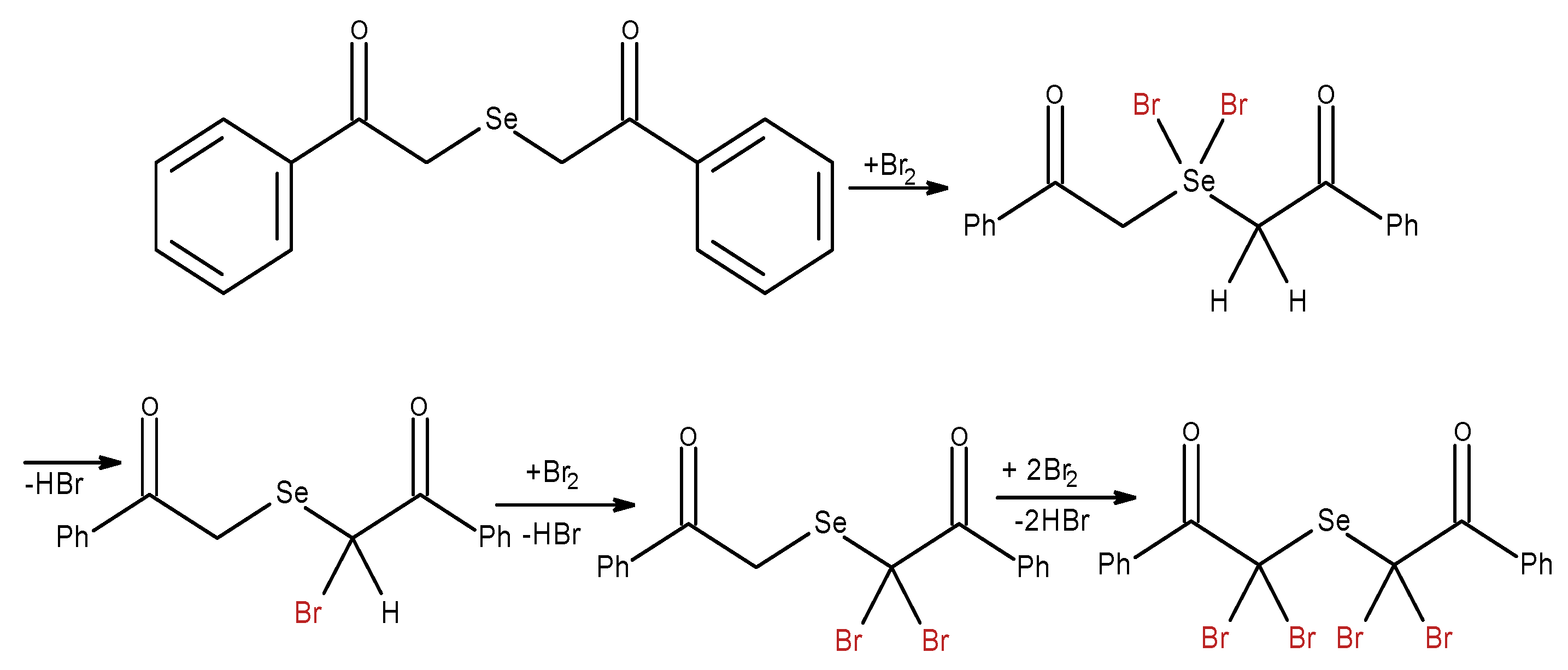

In our experiment, diacetophenonyl selenide reacts with electrogenerated bromine in stoichiometric ratio between diacetophenonyl selenide and bromine of 1:4, which differs from the literature [

38]. It is possible that bromination begins with the bromine attack on heteroatom (selenium) with further rearrangement, elimination of HBr and formation of alpha-substitution products (

Scheme 5).

At the end of coulometric titration, an increase in the voltage was detected reflecting a decrease in the bromine in the solution (

Figure 5). We believe that the reaction of diacetophenonyl selenide with bromine does not stop at alpha-bromination and is accompanied by electrophilic aromatic substitution in the benzene moiety.

The antioxidant capacity of diacetophenonyl selenide is superior to ebselene and selenopyran.

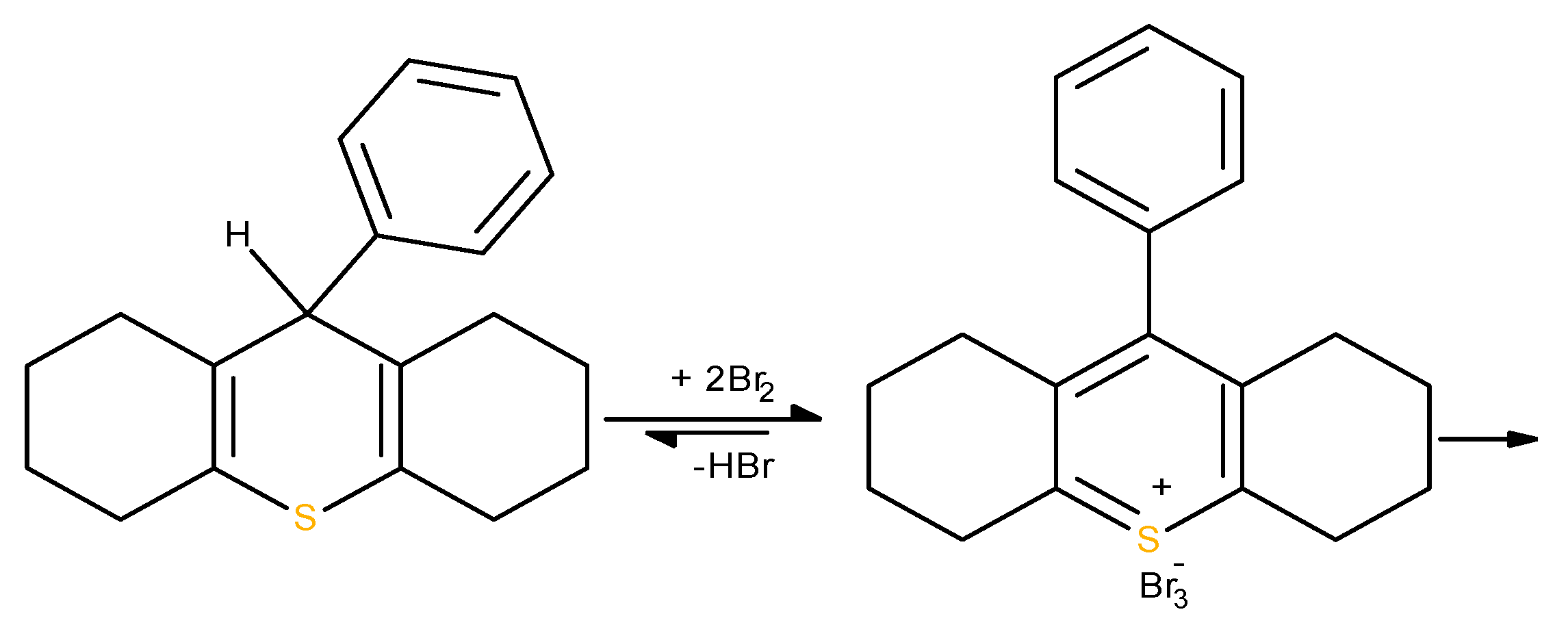

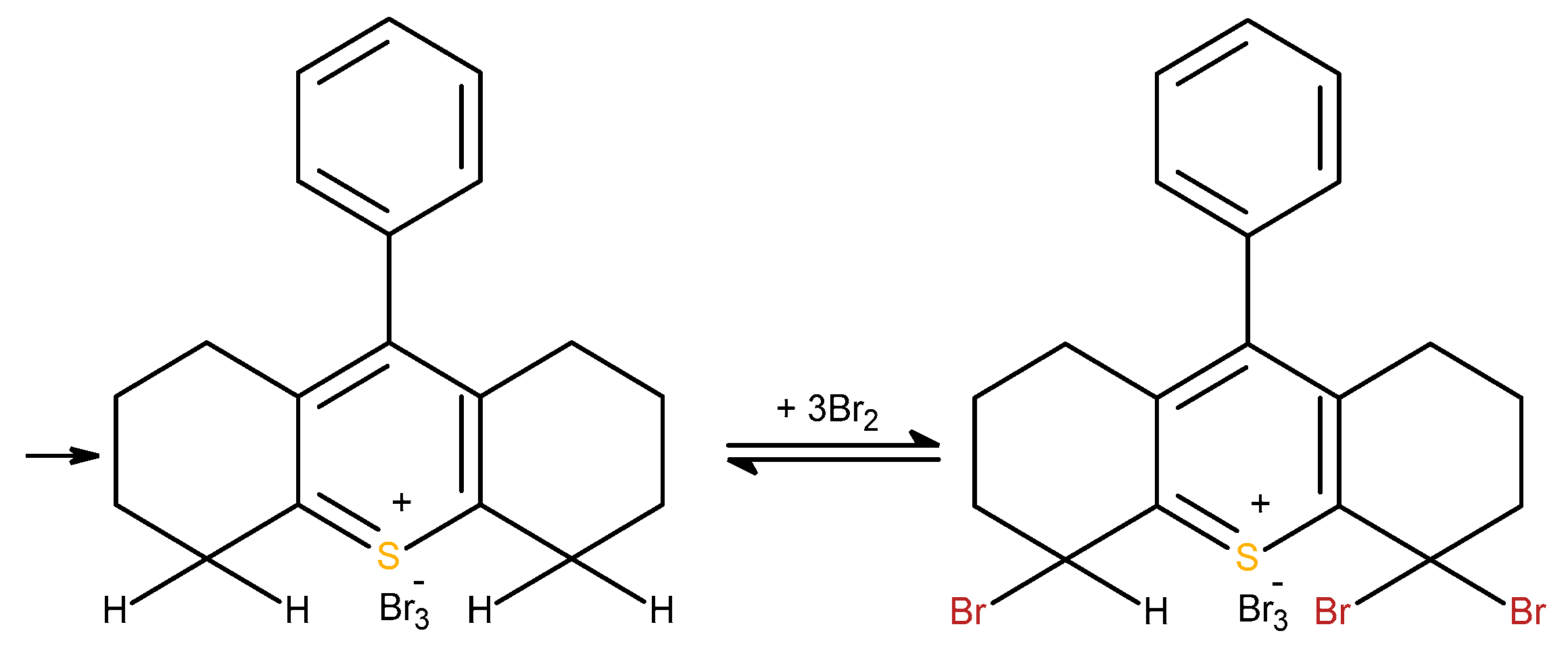

Thiopyran antioxidant capacity. Thiopyran (9-phenyl-cym-nona-hydro-10-thiaanthracene), and its selenium analogue selenopyran (9-phenyl-cym-nona-hydro-10-selenaanthracene) have close similarities as for their ionization potentials (thiopyran – 7.51-7.54 eV, selenopyran – 7.46-7.54 eV) and can be easily oxidized [

27]. Unlike selenopyran, the antioxidant activity of thiopyran has not been studied so far.

Monocyclic 4H-thiopyranes in reaction with bromine undergo heteroaromatization, and form substitution and addition products [

27]. Their analog thioxanthene, under the action of bromine, turns into perbromide of thioxanthylium [

39]. During photochemical oxidation, chalcogenpyrans form heteroaromatic cations [

40].

Thiopyran among the tested xenobiotics has the highest antioxidant capacity and reacts with electrogenerated bromine in a ratio of 1:5, similar to

L-cystine. As for

L-cystine/

L-selenocystine comparison, selenium compounds show lower antioxidant capacity then sulfur. Selenium is heavier and more polarizable, its higher oxidation states are less stable then sulfur. The oxidation of halcogenes involves the sequence of two steps. Although the first oxidation of sulfides/ selenides to sulfoxides/selenoxides is fairly comparable, with selenium being slightly more reactive, the second oxidation is more difficult for selenoxides. We propose that at the first step the coulometric oxidation of thiopyran gave tribromide of 9-phenyl-cym -octahydro-10-thionianthracene which has a lower electrode potential and can be brominated more easily than the starting thiopyran according to

Scheme 6.

The resulting coulometric bromination products, can consume free bromine, which is expressed in an increase in the voltage in titration (

Figure 6).

Antioxidant capacity of selenopyran. Experimental evidence of antioxidant activity of selenopyran (9-phenyl-simone-hydro-10-selenaanthracene) and its comparison with butyloxytoluene was obtained in vitro on thermal oxidation of methyl oleater. It was found that selenopyrane more effectively then butyloxytoluene reduced the amounts of peroxides [

27].

Selenopyrans, as well as their oxo- and thioanalogs, are easily oxidized by iodine in diethyl ether to form triodides. Relative activity of 9R-sim-nonahydro-10-oxa(chalcogen)anthracenes in this process do not correlate with their electrodonor activity and decrease in the order: pyran>thiopyran >>selenopyran, i.e. selenopyran was the most resistant to oxidaion by iodine. It is believed that the lower activity of selenopyranes compared with pyran and thiopyrane can be explained by the reversible formation of selenium diiodides, which slows down the iodination process [

27]. We beliene the bromination of selenopyrane included the similar steps. In our experiments selenopyran reacts with electrogenated bromine in a ratio of 1:2, a plausible mechanism for bromination is illustrated in the

Scheme 7.

At the end of coulometric titration of thiopyran and selenopyran as for diacetophenonyl selenide, we recorded an additional increase in the voltage, thiopyran has two and selenopyran has up to seven peaks (

Figure 7). We suggest the bromination-oxidation proceeds through the formation of mesomeric stabilized cation radicals, which can undergo further oxidation to sulfoxides, sulfones, as well as products of electrophilic substitution (bromination).

Constant-current coulometry in methanol allowed to compare sulfur- and selenium-containing antioxidants – amino acids and organic xenobiotics. Sulfur-containing antioxidants show higher antioxidant capacity than selenium ones. Among selenium-containing xenobiotics, diacetophenoyl selenide has superior antioxidant capacity (comparable to L-cystine), while selenopyran and ebselene are less active as antioxidants. We suppose that inconsistency between the ratio of reagents and stoichiometric coefficients in bromination of selenopyran and ebselene demonstrate further and side reactions which are more complex than a simple electron transfer. The structural peculiarity of selenium and aromatic moiety qualifiy them as prolonged antioxidants.

In general, the studied sulfur- and selenium-containing antioxidants can be divided into two groups. The first droup are brominated with electrogenerated bromine in one step and stoichiometrically, the second show an additional peak or even a number of peaks in a time dependence of voltage in coulometry titration curves associated with the formation of intermediates capable of further oxidation. The second group can be interesting as a mild prolonged antioxidants for further research.

Mimetic properties of L-

selenocystine.L-Selenocysteine is essential component of selenoproteins which act as an antioxidants by reducing of ROS [

41].

L-Selenocysteine can mimic the GPX, i.e. behave as a selenoprotein catalysts and involve in maintaining oxidative homeostasis without new free radicals [

42]. In comparison with direct antioxidants, nimetics are effective in low concentrations and are not consumed during reactions of elimination of ROS and free radicals.

Low-molecular-weight mimetics of superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase with anti-inflammatory, antitumor, immunotropic properties are potential therapeutic agents [

43,

44]. The effect of selenocysteine can be attributed to its higher reduction potential compared to cysteine, the ability to neutralize toxic peroxides and free radicals to counteract the effects of oxidative stress.

In our research, we investigated the mimetic properties of L-selenocystin, its ability to participate in both oxidation and reduction reactions. We conducted the electrochemical and chemical modeling of in vivo selenocystine reversible redox reactions.

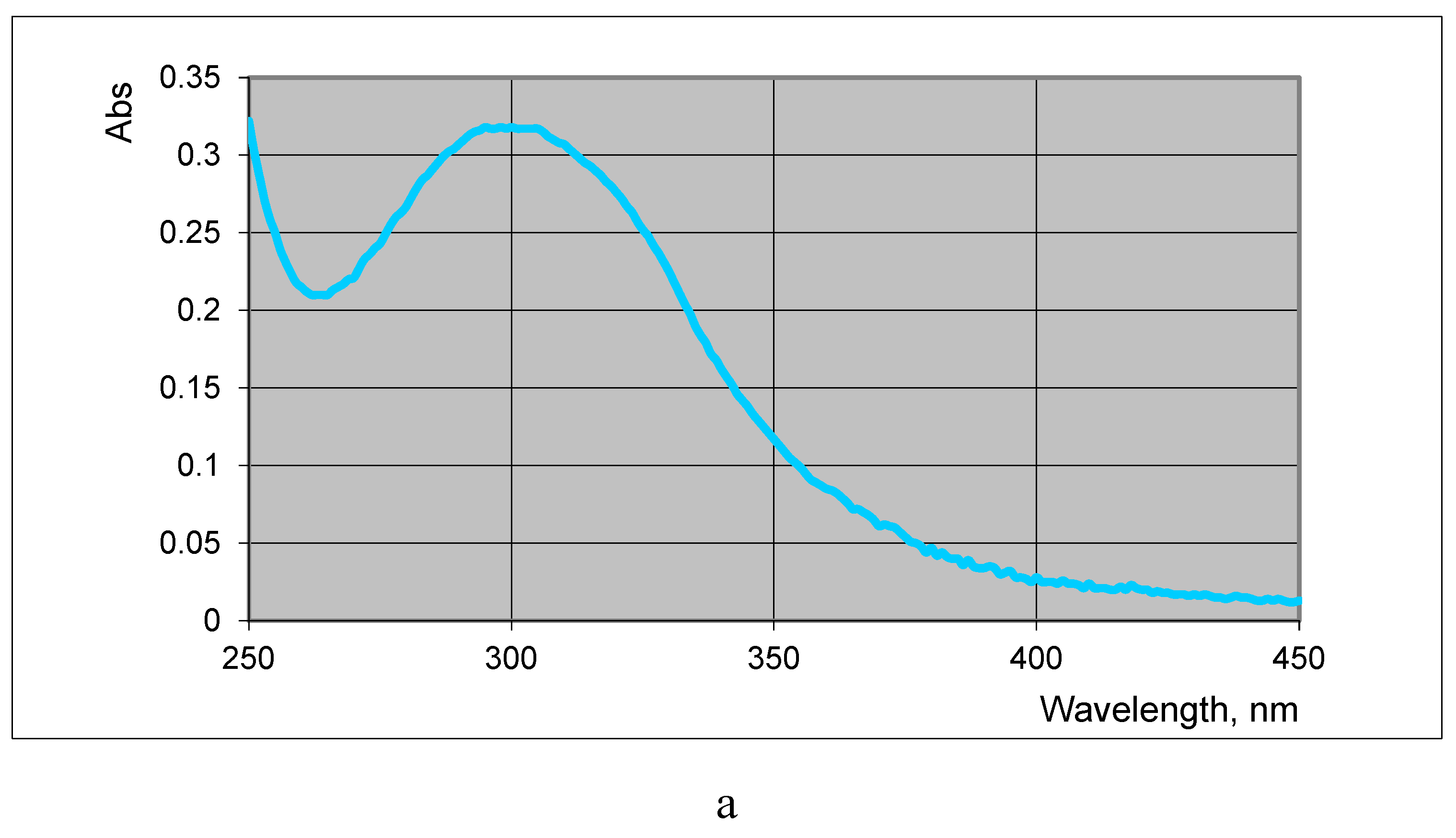

L-Selenocystine is soluble in acidic (0.1N HCl) and alkaline (1M Na

2CO

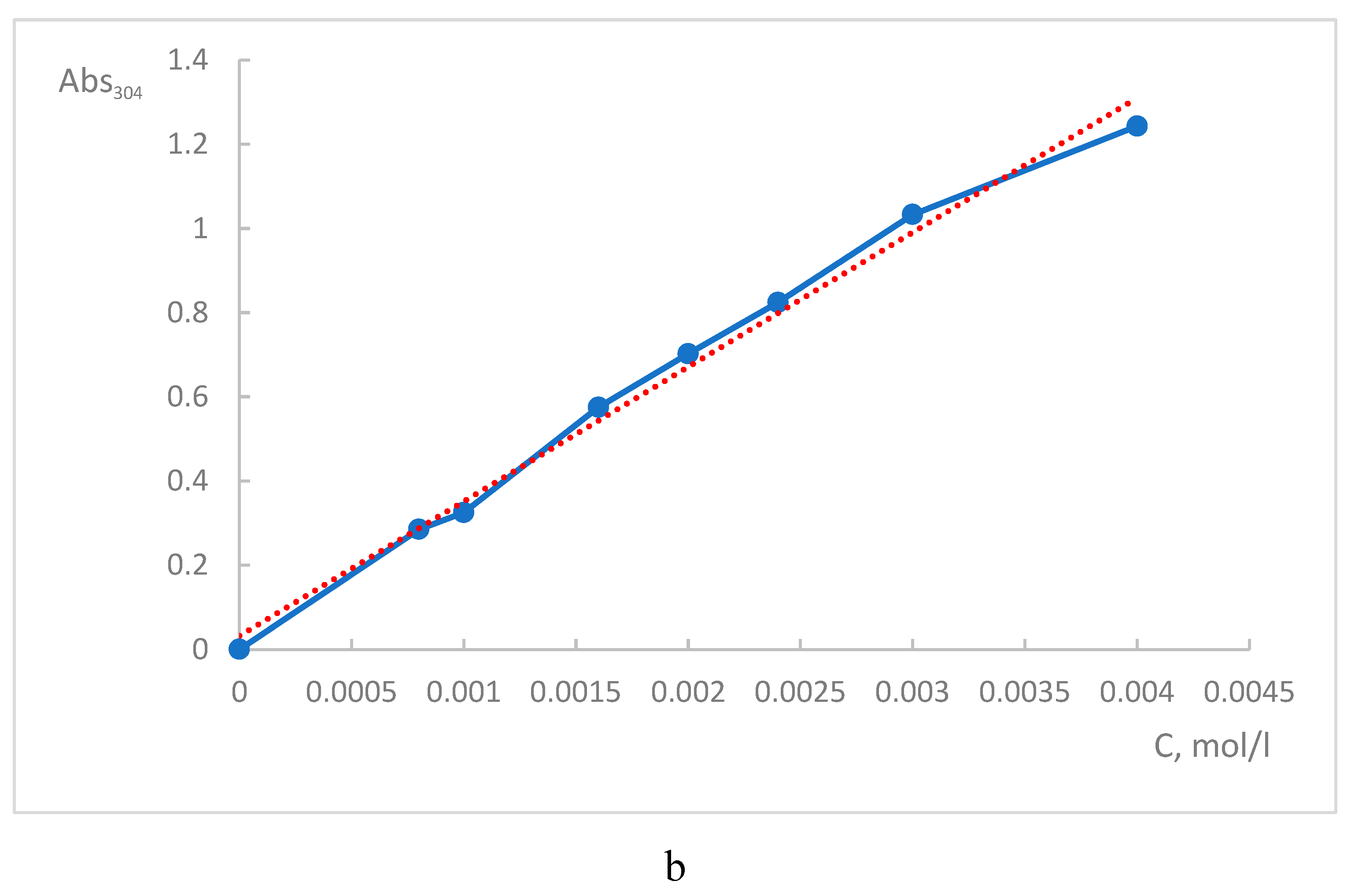

3) aqueous solutions. It was found that the selenocystine diselenide bond is a chromophore with an absorption maximum (λ

max = 304 nm) (

Figure 8а). The linear correlation were obtained between absorbance at 304 nm and concentration of

L-selenocystein. The molar absorption coefficient determined from the calibration plot was 340 M

−1⋅cm

−1(

Figure 8b). The absorption spectra of

L-selenocysteine (reduced form of

L-selenocystine) do not show any significant absorption in the 280-700 nm and do not have a maximum at 304 nm in contrast to

L-selenocystine.

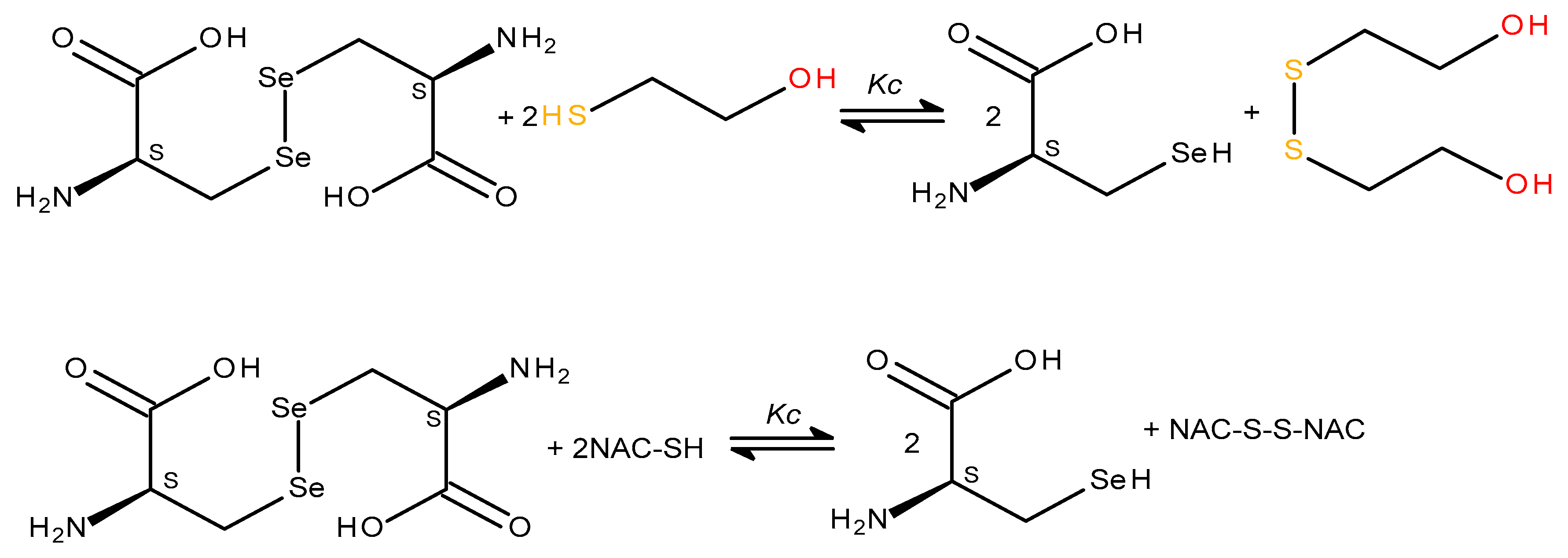

Therefore here we demonstrated the possibility to monitor the reversible redox conversion of selenocystin by spectrophotometry. At the beginning we carried out the reaction of selenocystine reduction. To determine the concentration of selenocystine we measured the absorbance before and after the addition of reductant. It was important to choose a suitable reducing agent. As glutathione does not reduce diselenides we selected the SH-containing lower molecular weight reductants - dithiothreitol and beta-mercaptoethanol (BME) which can reduce disulfides and diselenides [

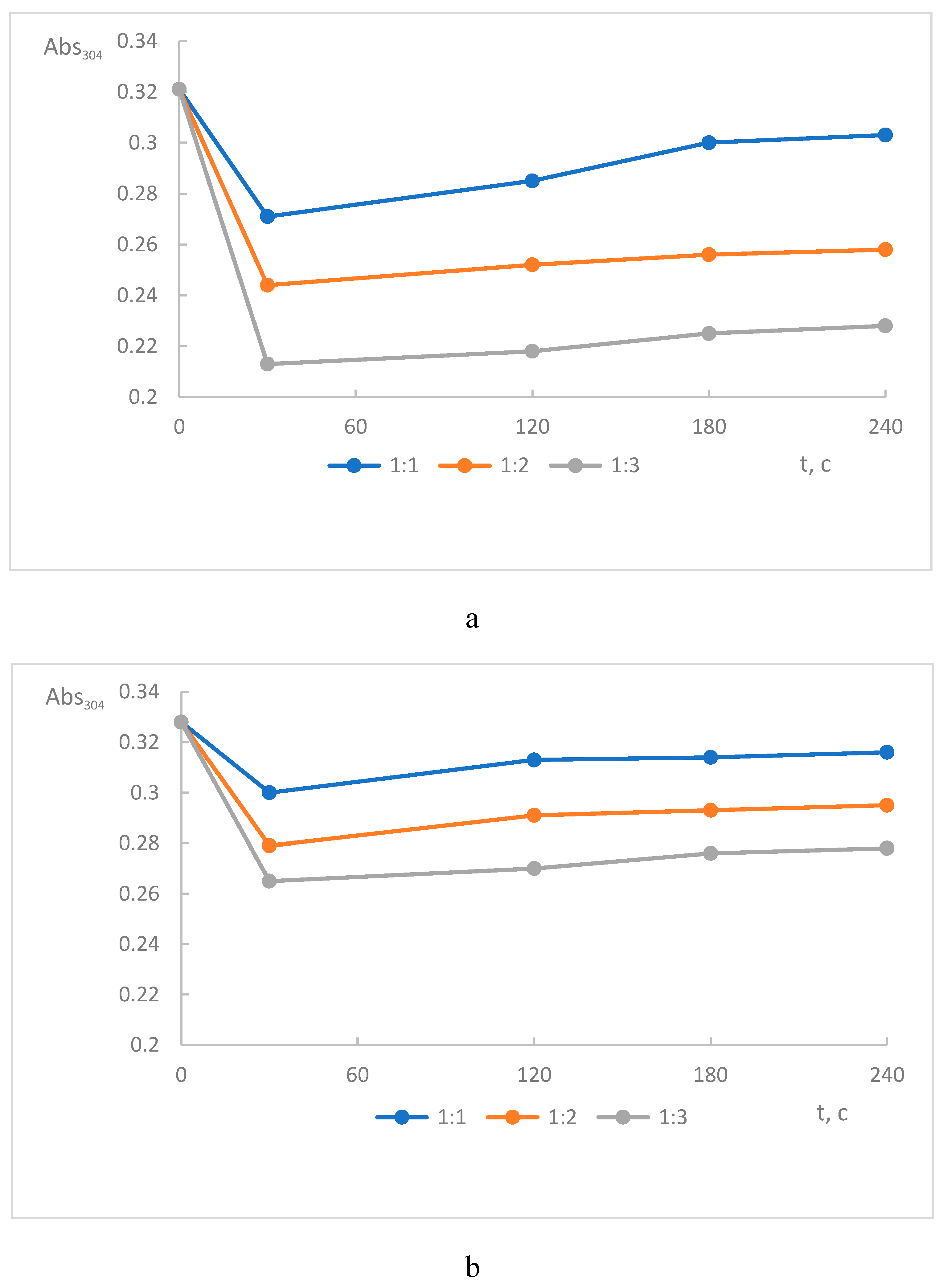

45]. We excluded dithiothreitol as for its inability to participate in reversible reactions - the oxidation product of dithiothreitol is a cyclic intramolecular disulfide, which is not able to form a selenosulfide bond. In our reversible reactions, we use BME and N-acetylcysteine (NAC), as a reductants. NAC is a registered mucolytic drug, it is in vivo reducing agent which degrade the mucus network by reducing the disulphide bonds. It was interesting to study the possibility of NAC to reduce diselenides and compare its reducing ability with traditional mercaptoethanol.

The addition of BME to selenocystine almost immediately resulted in decrease in the absorbance at 304 nm indicating the reduction of the diselenide bond. Next, within 20 minutes, the absorption increases slightly, which indicates the reverse oxidation of the selenol groups of L-selenocysteine, assuming the equilibrium between initial selenocystine and reduced selenocysteine (

Figure 9а).

Increase the BME concentration (the original reductant) resulted in more dramatic decline of the final absorption at 304 nm and therefore the degree of selenocystine reduction. We propose the scheme of selenocystine reversible conversion (

Scheme 8). Experimental data indicate the equilibrium between the product and the original selenocystine. So to shift the equilibrium towards products, a large excess of mercaptoethanol is needed, since even with a threefold excess, the diselenide consumption was 37.4%.

NAC, like mercaptoethanol, reduces the selenocysteine diselenide bond. When NAC was added to the selenocystine solution , a dose-dependent decrease in absorption was also observed at 304 nm, indicating the disappearance of the diselenide chromophore (

Figure 9b). The reaction was completed instantantly, reversible, but the degree of conversion (reduction) of selenocystine in the presence of NAC was lower than with BME. Therefore NAC is a less effective reductant then BME, probably because of steric hindrance created by bulk acetyl and carboxyl groups. The scheme of the redox

L-selenocysteine/

L-selenocystine equilibrium is shown in

Scheme 8.

Initial and final L-selenocysteine concentration was calculated by Beer–Lambert law, and the equilibrium constant (Kc) (

Table 1) was determined taking into account the stoichiometry of the process (

Scheme 8):

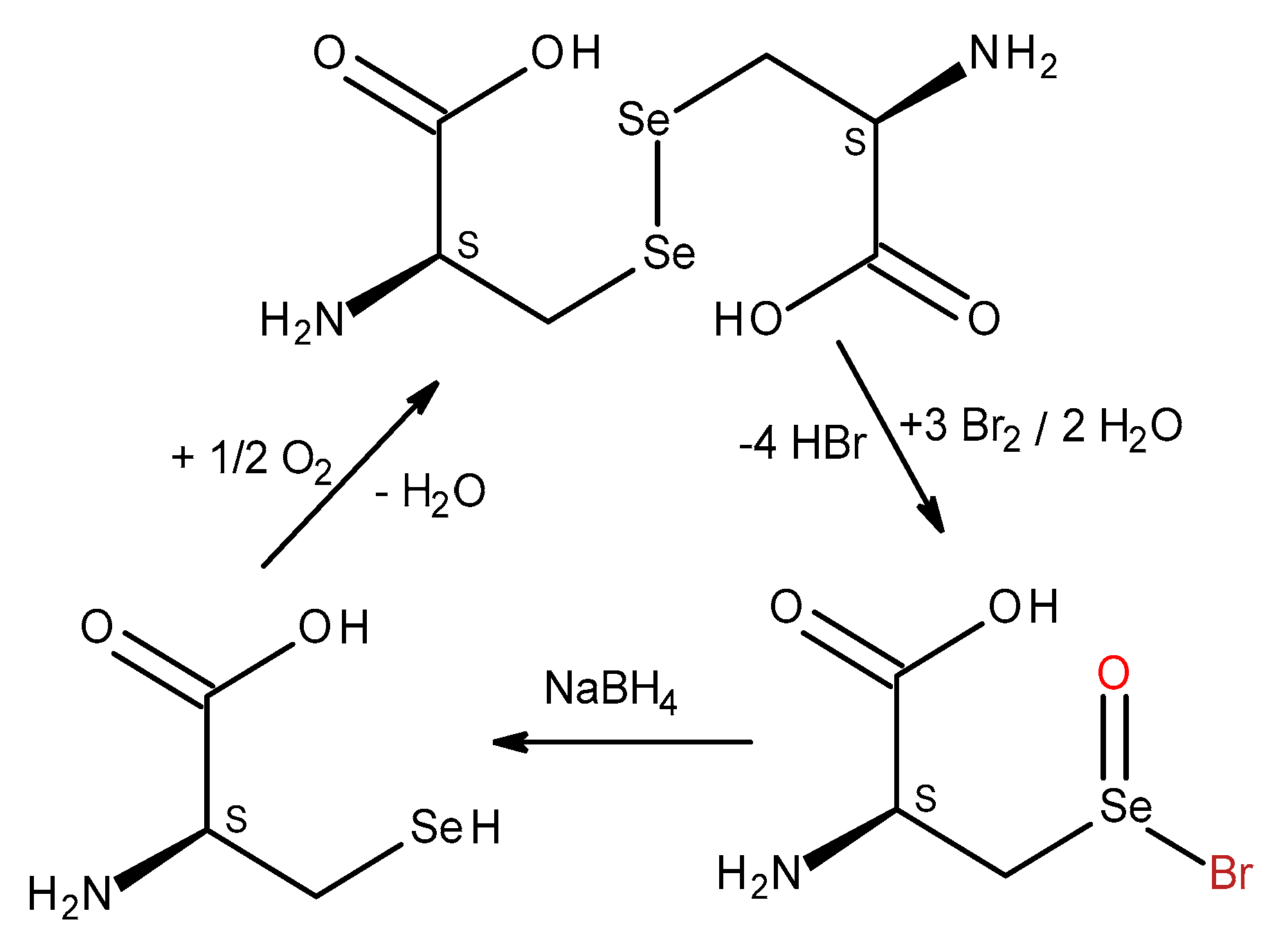

To prove the mimetic properties of

L-selenocystine to act as in vivo redox switch we aimed to demonstrate the possibility of its reduction after oxidation. The initial and final concentration of

L-selenocystine were measured by coulometric titration developed previously (

Scheme 2).

To simulate in vivo redox switch functions of

L-selenocystine (

Scheme 9), we oxidized it with electrogenerated bromine, and then performed the reverse reaction (reduction) of the coulometric bromination product (2-amino-3-bromoseleninylpropanoic acid) to the corresponding selenol under the action of sodium borohydride (30 min). The excess of reductant was hydrolyzed by sulfuric acid, then bubbled into the reaction mixture (pH 8.0) air (1 hour). We believe that under these conditions,

L-selenocystine was formed – the solution turned yellow, an absorption peak appeared at 304 nm (chromophore, diselenide bond), and 92.2-95.9% of selenocystine have been regenerated.

Thus, L-selenocysteine can be reversibly oxidized, reduced, have a mimetic properties, a low-molecular-weight analog of glutathione peroxidase.

4. Materials and Methods

General Experimental. The following reagents were used in the work:

L-Cystine and

L-methionine were from the set of amino acids LAA21 (Sigma-Aldrich, United States),

L-selenocystine was synthesized by the method published earlier [

46], ebselene was synthesized according to the method [

47]. 0.01M solutions of aminoacids were prepared in background electrolytes or 1M Na

2CO

3 solution. Thiopyran, selenopyran, diacetophenonyl selenide were kindly provided by Professor of Penza State Agricultural University Boryaev G.I. Solutions were prepared in distilled water and in methanol.

Antioxidant capacity assay. The total antioxidant activity of tested substances was determined on a coulometric analyzer Expert-006 (Econix-Expert, Russia) according to Lapin’s method [48]. Electrogeneration of halogens was carried out in Expert-006 coulometric analyzer at a current 5.0 mA in water solutions (0.2 M KBr in 0.1 M H2SO4) and at a current of 50 mA in 85% methanol (0.1 M KBr in 0.3 M HCl).

Coulometric determination was carried out in a 50 ml cell into which 30 ml of a background solution was added, then the electrodes were applied and the electrical circuit was turned on. Upon reaching a certain value of the indicator current, (0.1 cm3), 10 μmol of the tested samples, accurately prepared at a known concentration were added into the cell. Aminoacid samples were in water solutions, ebselene, thiopyran, selenopyran, diacetophenonyl selenide were in 85% methanol. The amount of electricity (coulomb, Q, C) spent on the generation of bromine was determined automatically by the device. Antioxidant capacity was determined as the amount of electricity used to titrate 10 μmol of tested substances. All values were measured in triplicate at least and averaged.

Reduction of selenocystine. L-Selenocystine (0,01M stock) was dissolved in 1M Na2CO3, then tested solutions (0,001, 0,002, 0,003M) were prepared and their absorbance were measured. Mercaptoethanol/N-acetylcysteine (0,1M in 1M Na2CO3) were added to the Selenocystine solutions in the rations selenocystine – reductant 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, stirred for 30 sec. The resulted absorbance were measured spectrophotomerically every 60 sec for 6 min.

Mimetic properties of L-selenocystine. Oxidation of L-selenocystine was performed in coulometric cell. 30 ml of a background solution was added to the cell, then the electrodes were applied and the electrical circuit was turned on. Upon reaching a certain value of the indicator current, L-selenocystine solution (3 cm3), 0.01M in 0,1M HCl) was added into the cell. The amount of electricity (coulomb, Q, C) spent on the generation of bromine was determined automatically by the device.

Reduction of 2-amino-3-bromoseleninylpropanoic acid (a product of coulometric bromination) to the corresponding selenol was carried out in the presence of 50 mg sodium borohydride (30 min), the excess of NaBH4 was hydrolyzed with sulfuric acid (pH was controlled to pH 2). Then pH was adjust to pH 8 by sodium carbonate and diselenide bond was formed by bubbling the air in the resulting mixture (1 h).

Oxidation of the product of the reduction was performed in coulometric cell similarly to the initial oxidation.

All values were measured in triplicate at least and averaged.

Absorption spectra of selenocystine were recorded in a 1 M Na2CO3 on Spectrophotometer SF-201 (ZAO NPKF Akvilon, Russia).