Introduction

Technological advancements, globalization, increasing costs of agricultural inputs, changes in consumer preferences, climate variability, and extensive market fluctuations are driving changes globally affecting the farm sector [

1,

2]. Consequently, farming is becoming more competitive and demanding, while its importance is diminishing in many rural communities [

3]. These problems have resulted in the consolidation of many farms and the adoption of non-farm employment to provide medical insurance or additional income [

4]. Therefore, producers are encouraged to adopt an entrepreneurial culture to promote agricultural sustainability and remain in business. Agricultural entrepreneurship is the ability of farmers to pursue a new type of farming that encourages innovation and strategic planning [

5], leading to agricultural sustainability, a farming system aiming at soil and water conservation and promoting human health [

6,

7,

8].

Sustainable agriculture encourages land preservation and seeks to reduce the environmental, social, and economic impacts of agriculture, such as an increase in input costs, land degradation, and soil and water pollution [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Sustainable agricultural development, however, requires embracing entrepreneurial culture, a new agricultural model that focuses on multifunctionality (economic, social, and environmental functions) and encourages farmers to be innovative [

13]. Adopting agricultural entrepreneurship enables farmers to be competitive, seek and recognize new opportunities, and balance environmental conservation and profit maximization [

12,

14,

15,

16]. It secures adequate financial resources that help farmers to adopt the best management practices (BMPs) and technology, thus achieving agricultural sustainability [

17,

18].

As farmers adjust to meet changing market demands and increased climate and weather variability, a better understanding of the drivers of entrepreneurship adoption among agricultural producers is necessary. The literature shows that the need for the adoption of entrepreneurship in the broader rural context is growing as many farmers are forced to incorporate off-farm practices into farm business to increase profitability and income [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Although these issues challenge all farmers, this study used farmers in eastern South Dakota (SD) as a model system to examine their entrepreneurial aspirations. Entrepreneurial aspirations refer to the desire, ambitions, intentions, and motivations that encourage business owners to think entrepreneurially and innovatively, seek opportunities, and constantly learn and promote self and business development [

23,

24]. The study site was selected because it is in the transition zone between the cold semi-arid and hot summer humid continental Köppen climate regimes. Farmers in this model system do not have access to many natural resources that allow them to reduce the effects of a changing climate on their economic risk and profitability. A detailed discussion about climate variability and its impact on land use and crops and soils in this model system is found in [

25,

26].

This paper seeks to answer the following questions: 1) What are the entrepreneurial aspirations of western U.S. Corn Belt farmers? 2) What factors influence entrepreneurial decisions in this model system? 3) To what extent do socio-demographic characteristics of farmers, such as age, education, and farm size, influence their decision to adopt entrepreneurship, use social networks, and engage in training?

Literature Review

Developments in the Field of Agricultural Entrepreneurship

Agricultural entrepreneurship can be understood from a broader perspective of entrepreneurship. Farm entrepreneurship includes business expansion, leadership development, and acquiring managerial and entrepreneurial skills. However, farmers operating in a different setting than urban businesses need other methods and conceptualizations to investigate agricultural entrepreneurship [

15]. Additionally, the relationship between farmers and farm operations is complex because the farmer can be an owner, a tenant, a manager, a subcontractor, or can simultaneously engage in more than one of these roles [

19], which requires farmers to acquire different managerial and entrepreneurial skills that will help them succeed in their businesses. Like [

22] and [

27], we believe that many current US western Corn Belt farmers need to further their managerial skills and gain an entrepreneurial sense of business operation. Land management policies and practices that do not promote agricultural entrepreneurship discourage farmers from acquiring advanced managerial and entrepreneurial skills and adopting long-term strategic planning. Evidence from the literature suggests the need to restructure the agriculture sector to include the entrepreneurial aspect of farm business and to revise policies that do not encourage the adoption of entrepreneurship [

15,

28,

29].

Restructuring agriculture includes transforming farming operations from conventional to multifunctional and entrepreneurial businesses and shifting from production to market-oriented [

30]. In non-conventional agriculture, each market has specific requirements. For example, for organic markets, there is a need for land certification and nonuse of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Although conventional and non-conventional farmers produce products for various markets, they require different skills. Conventional farming, which often relies on heavy chemical use and tillage, usually requires less professional and organizational skills and competencies (the knowledge and skills that farmers could pass down generationally) that are acquired through formal training and education [

30,

31].

In contrast, entrepreneurial agriculture or a market-based system requires advanced professional and organizational skills and competencies. These skills are obtained through formal training and education instead of being transferred from generation to generation. This approach also requires managerial and entrepreneurial skills, discovery and exploitation of opportunities, attention to timing and detail, and adoption of strategic planning [

29]. Education, farm size, and age impact farmers' adoption of entrepreneurship, use of social networks, and engagement in training. The younger and more educated the farmers, the more likely they would adopt entrepreneurship and agricultural BMPs [

32,

33].

Furthermore, entrepreneurial agriculture requires farmers to adopt strategic, tactical, and operational planning. Strategic planning involves short-term and long-term decision-making, tactical planning is concerned with short-term decision-making toward the progress in production, and operational planning involves performing tasks such as planting and harvesting [

34]. Some existing literature indicates that many farmers, including those in developed counties, need more strategic plans with a clear vision and mission statement supported with objectives and goals [

28]. Even those who adopt strategic planning regularly focus on short-term strategies in their operations rather than adopting long-term strategic planning [

35]. Also, farmers with advanced management and strategic planning skills are more likely to manage their financial resources and reduce input costs efficiently [

28]. To acquire these entrepreneurial and managerial skills or enhance their existing ones, farmers may utilize their social connections, education, and training, referred to as social capital and human capital, discussed next.

The Role of Human and Social Capital in Farm Entrepreneurship

Human capital and social capital influence farmers' values, goals, decision-making, and strategies. Human capital refers to skills, knowledge, and capabilities that farmers acquire through education or training, which they use to learn new innovative ideas to manage their operations [

8,

36]. Social capital includes the existing social contacts and ties between farm operators that can be used to access information, knowledge, and resources regarding new practices from external organizations such as consulting agencies and professional associations and clubs and seize opportunities about the market and BMPs [

36,

37]. Literature shows that education, age, length of farming experience, constant participation in training, and building and utilization of social networks can all influence farmers' motivations and goals to adopt conservation practices [

38]. Social capital also helps farmers access funding opportunities and business services such as business consulting [

39]. Human and social capital, which are interrelated, also determine strategies farmers use to enhance their economic success, keep up with business demands, and achieve agricultural sustainability [

39]. For instance, participating in business training opportunities can help farmers learn strategic planning and record keeping, which enhances their business management strategies. Similarly, by adequately accessing information through participating in local conferences, training workshops, and being involved in neighborhood connections, farmers can share information about the new innovative ideas and the BMPs used by other farmers [

19].

Moreover, producers can acquire human capital in different ways. Whereas some farmers enter the agriculture sector with entrepreneurial skills, others develop these skills after they enter the sector. The existing literature shows that previous experience in entrepreneurship and farm operation and management, farmers' age, and education influence farmers' entrepreneurial success [

35,

40]. Entrepreneurial success refers to the ability of business owners to expand their operations, increase the profitability and sustainability of their firms, and establish personal wealth [

41]. Business owners with prior knowledge and experience in farming are more likely to recognize, evaluate, and use entrepreneurial opportunities because these skills, along with information, underlie individuals' tendency to explore entrepreneurial opportunities. Entrepreneurial opportunities in an agricultural context refer to the creation of new ideas, innovations, and social networks that can help to increase funding sources, access to training and business advice, and adoption of crop diversification, for example [

10,

27].

Social networks play an essential role in the entrepreneurial success of farmers because they enhance entrepreneurial opportunities that help farmers to learn innovative ideas or BMPs and access funding opportunities, referred to as diffusion of innovations. Diffusion of innovation theory focuses on how information or ideas about innovations are disseminated through existing social networks [

42,

43]. In this case, the diffusion of innovation theory helps us understand the likelihood of spreading certain practices among farmers. In particular, farmers have strong social connections with their families, relatives, peers, neighbors, and other farmers that facilitate the spread of innovative ideas and help them to access information and learn about innovative and technological methods that other farmers may have adopted [

44,

45].

In summary, to remain in business today, agricultural producers need to constantly assess their entrepreneurial skills and strategies, use their social networks to learn new innovative ideas and engage in continuous professional development to update and refine their skills, knowledge, and competencies. Although farmers encounter significant challenges today, the literature shows that enhancing their competencies can improve their market competition and increase farmers' adoption of environmentally friendly practices [

46]. According to [

34] and [

47], farmers should prioritize engagement in strategic planning, including the development of formal (written or unwritten) business plans and the design of precise long-term goals for their farm activities. Having strategic business plans and regularly evaluating and adjusting them helps farmers think strategically and achieve better outcomes [

47]. Also, business plans are not static; they must be reviewed annually to ensure adjustments are needed [

9]. Although it requires time, which many farmers might still need to commit to, strategic planning allows farmers to better plan for future events, thus creating flexibility in resource management [

28]. There needs to be more research on agri-entrepreneurship and its role in the development of farm businesses [

48].

Additionally, previous studies have given less attention to the entrepreneurial aspirations of farmers in the US western Corn Belt and strategies that farmers can use to overcome the ongoing economic challenges they are experiencing due to recent changes in agriculture [

49]. Thus, in this study, we examine the extent to which producers believe adopting entrepreneurship is crucial to succeed economically. We also analyze whether education, farm size, and age affect farmers' decisions in South Dakota to adopt entrepreneurship, use their social networks, and seek training opportunities.

Hypotheses

Based on the existing literature reviewed, we have developed the following hypotheses: H1: Larger farm operators are more likely to have entrepreneurial aspirations. H2: Larger farm operators are more likely to perceive building social networks and seeking training opportunities as essential to their farm operations. H3: Younger farmers are more likely to have entrepreneurial aspirations. H4: Education is positively associated with farmers' entrepreneurial aspirations. H5: Farmers who seek training opportunities and regularly update their knowledge are more likely to be entrepreneurial. H6: Farmers with more robust social networks are more likely to have entrepreneurial aspirations and access training opportunities.

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

The study region is in a climate transition zone, stretching from a tallgrass prairie in eastern South Dakota to a mixed grass prairie in central SD. The Köppen climate regime for the area is humid continental, and annual precipitation is 51.1cm. In addition, climatic predictions indicate that the number of extreme events (e.g., flooding, drought, temperature extremes, intense storms) and warming trends (e.g., earlier springs, greater growing degree days (GDD) per growing season) will increase over the next 20 to 50 years [

50,

51]. Essential agricultural products include corn (

Zea mays), soybean (

Glycine max), wheat (

Triticul aestivum), livestock, and ethanol. In eastern SD, corn is the primary source of ethanol and its coproducts.

Through a Freedom of Information Act request, we obtained a list of 10,000 farming operations participating in 2016 Farm Service Agency (FSA) programs. For our sampling purposes, we targeted farm operations in 34 South Dakota (SD) counties east of the Missouri River, where most of the state's corn and soybean farming activities are located. We then selected 3000 operations using proportionate stratified random sampling according to the number of farming operations in the study counties. We assigned a unique code to each subject as an identification number. The questionnaire directed the person in the operation who made most land management decisions to answer the questions. Those in the sample were first sent an advance letter (one-half with a

$2 bill to test if it increased response rates) with the link to answer the questionnaire online. Mail surveys with addressed and stamped return envelopes were then sent to those who did not respond, followed by a reminder postcard two weeks later and a second paper copy of the survey after the stated two weeks, following the Tailored Design Method [

52]. The survey was conducted from January through March of 2018; 650 surveys were returned for wrong addresses or producers, indicating that the operators did not currently farm any land. We received a total of 708 responses for a 30% response rate.

The survey included N=11 entrepreneurial items which focused on three themes, (a) how farmers think and plan entrepreneurially, including plans to adopt agricultural sustainability in their farming operations (N=5), (b) farmers' use of social networks to learn new and innovative ideas and increase their awareness of funding opportunities (N=3), and (c) farmers' use of training and knowledge to be entrepreneurial (N=3). A variety of questions, such as operation and operator characteristics, usage of conservation practices, and operator attitudes, were included in the survey. These questions were asked on a four-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree, 2=agree, 3=disagree, 4=strongly disagree).

Data Analysis

Data were entered into QuestionPro software (by producers taking the survey online and by research assistants for those who took the mail version), extracted as Excel files, then cleaned and put into SPSS software. Three scales using the entrepreneurial items were created by summing the eleven items included in the survey (see

Table 1). The reliability of the scales was tested using Cronbach's alpha, and each item was tested individually for its improvement of the reliability of the scale (alpha if removed). In this respect, the Cronbach's alpha for the Entrepreneurship Scale with five items was 0.71, 0.84 for the 3 item Network Scale, and 0.72 for the 2 item Training Scale after the deletion of one item for its lack of contribution to the reliability of the scale (attendance at XXXX Extension workshops).

In this section, we present results from bivariate analyses (Spearman's rank-order correlation) that examined relationships between socio-demographic factors, the three entrepreneurialism scales, and between training/networks and entrepreneurialism. We also used bivariate (t-tests and ANOVA) statistics and multivariate analysis (multiple regression) to test the relationships between age, education level, and farm size on farmers' attitudes to adopt entrepreneurship, use their social networks, and participate in training programs that different public and private institutions provide. Only valid percentages are reported, and missing cases are excluded (pairwise deletion).

Results

Key Farmer and Operation Characteristics

Most survey respondents were males (97.2%), and 73.2% were 50 years old or above, with an average age of 57.7 years, which aligns with data from the SD Department of Agriculture (2017) that shows a rancher or farmer's average age in 2017 was 56 years. Regarding their education level, respondents reported as follows: 2.5% less than high school, 25.1% high school graduates/GED, 34.7% some college/technical school, 32.0% college graduates, and 5.7% post-graduate degrees. Regarding farm size, 38.6% of participants reported that the number of farm acres they operated in 2017 ranged from 1-499 acres (an acreage the Economic Research Service (ERS) considers small), 23.1% reported operating farms that ranged from 500-999 acres (large farms), and 38.3% stated they operated very large farms (1000+ acres). The average number of acres operated was 1,150, slightly smaller than the average in SD of 1,397 (SD Department of Agriculture, 2017).

Thinking and Acting Entrepreneurially

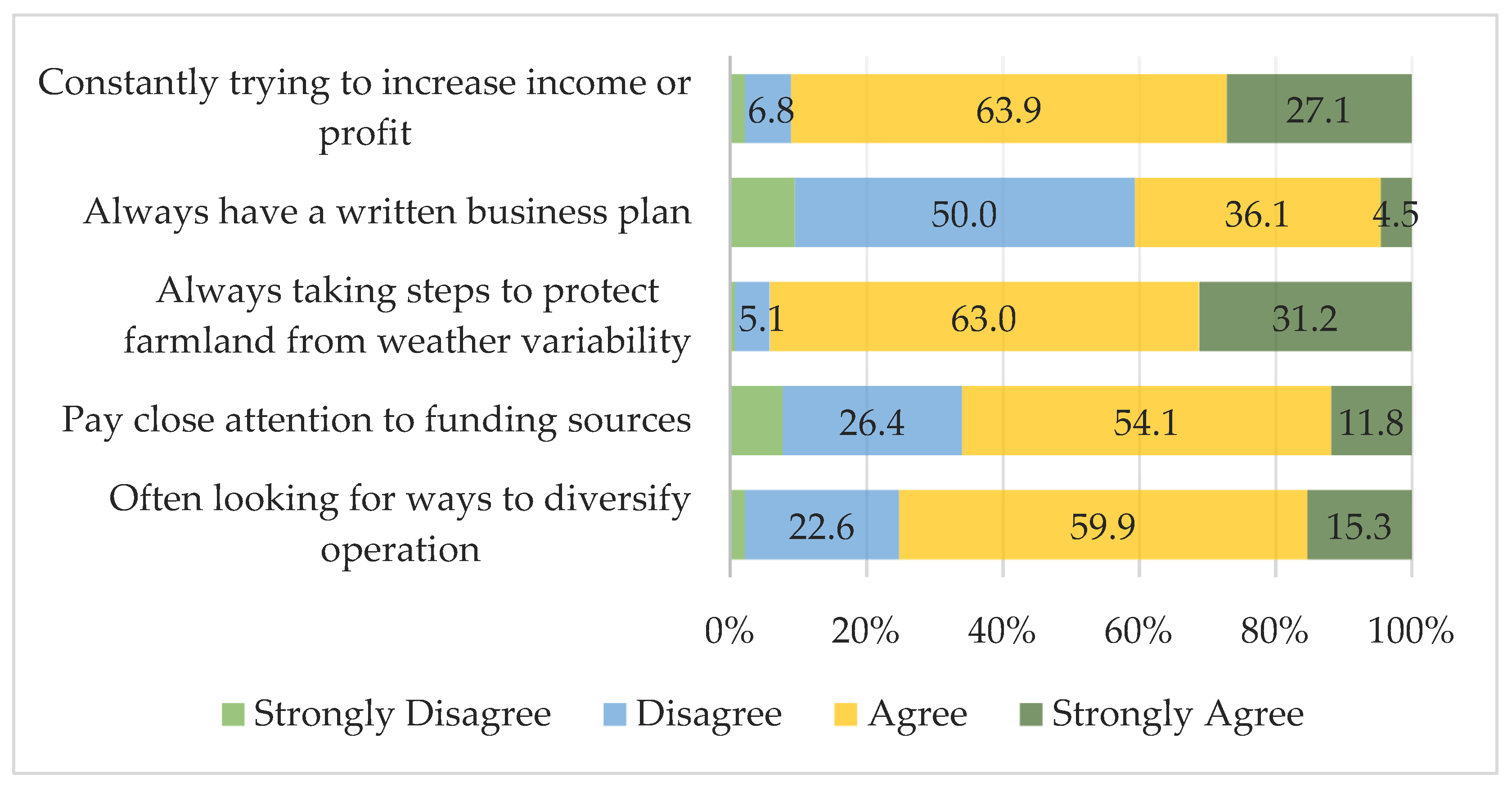

In terms of whether commodity crop farmers in Eastern SD think and act entrepreneurially (see

Figure 1), the highest percentage strongly agree (31.2%) that "I am always taking steps to protect the land I farm from increased weather variability (e.g., diversify crops, build soil quality, adding drainage or irrigation systems)." A high percentage also strongly agree (27.1%) that "I am constantly trying to find ways to increase my income or profit (e.g., creating new ideas, finding new innovations, trying various technologies and management practices)." Most producers also agreed (strongly agreed and agreed) that they pay close attention to funding sources and are often looking for ways to diversify their operations. The only statement that most respondents disagreed with was having a written business plan. Nearly sixty percent (59.5%) disagreed or strongly disagreed that they always had one.

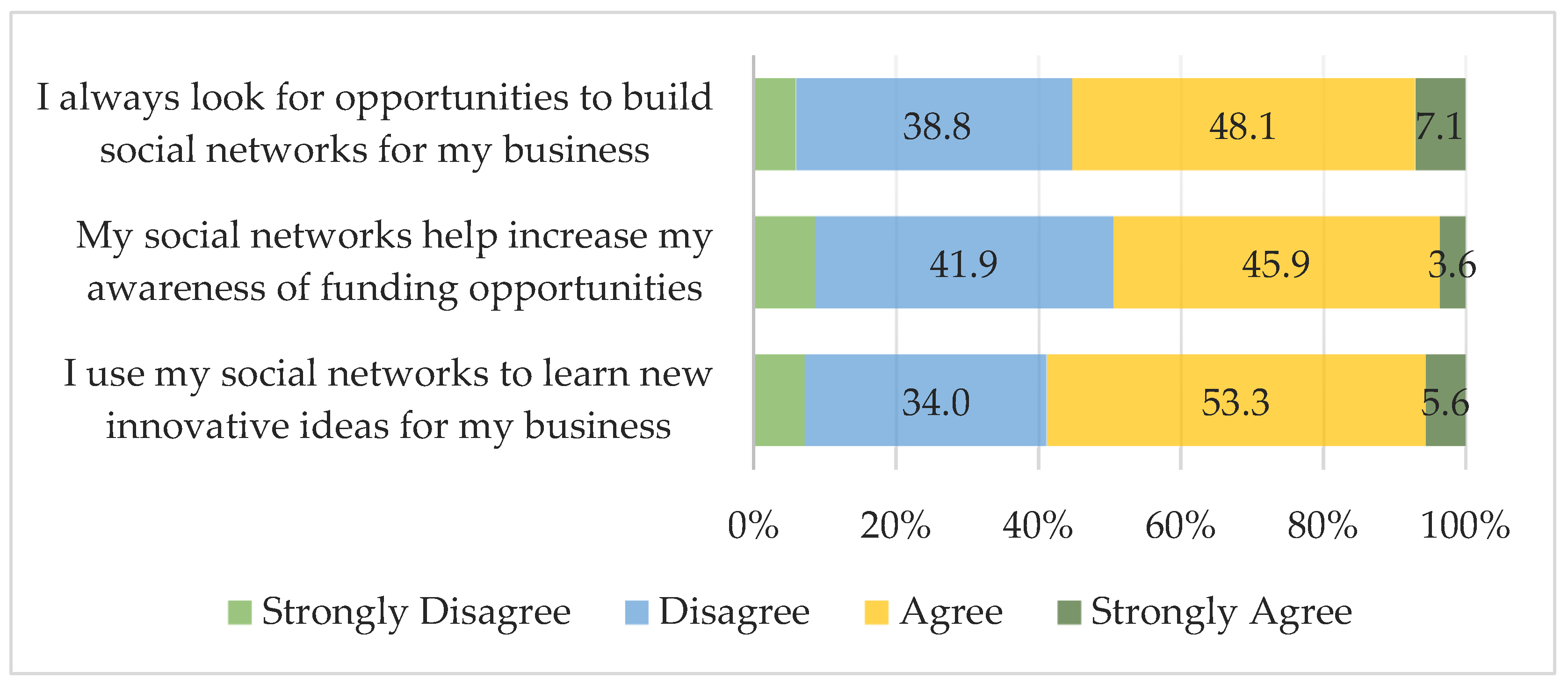

About one-half of respondents agreed (agree and strongly agree combined) with all three statements regarding the importance of social networks to their farming business (see

Figure 2). Respondents were most likely to agree that they look for opportunities to build their social networks for business opportunities, followed closely by agreement with social networks helping to increase awareness about funding opportunities, and lastly, usage of social networks for innovative business ideas.

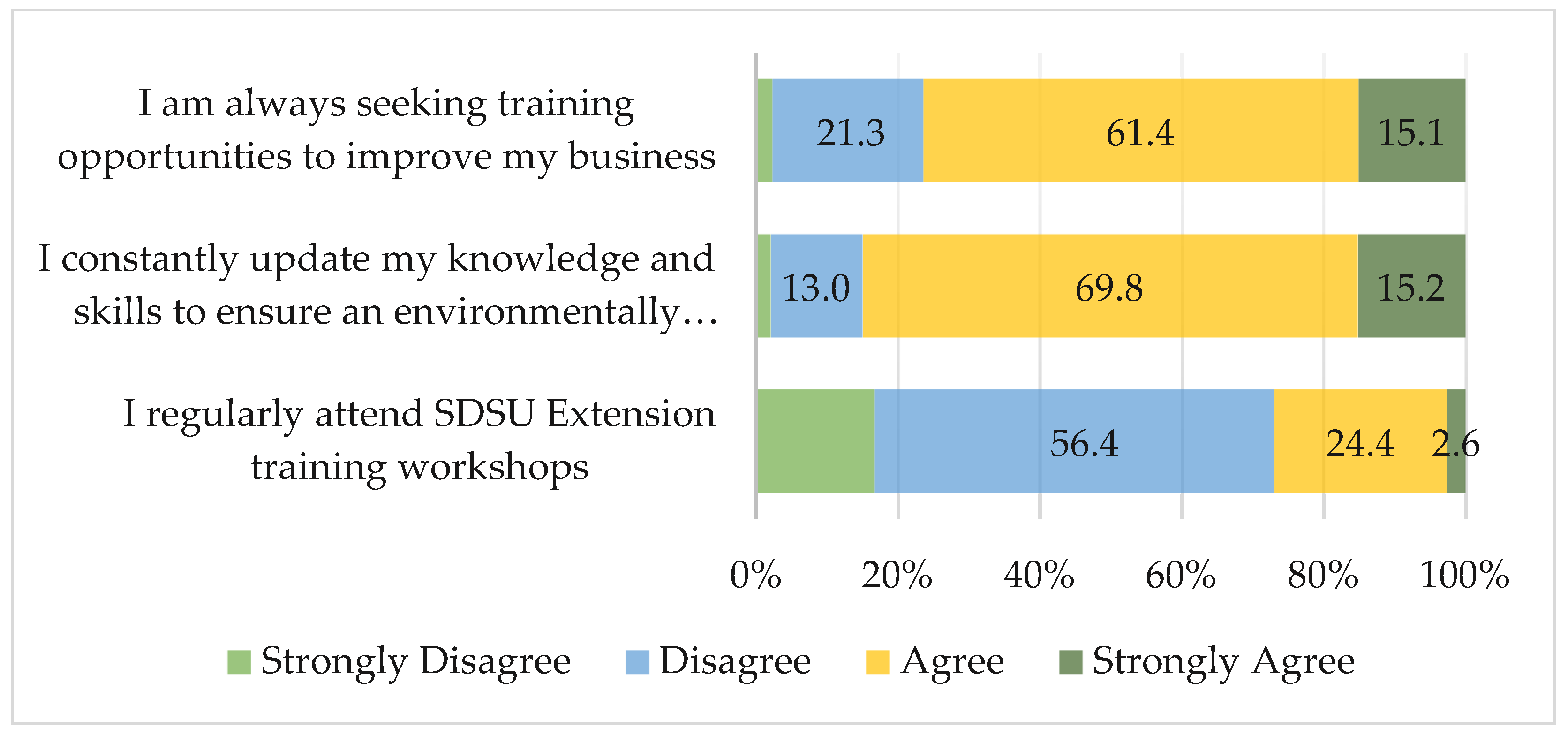

While most respondents agree that they are often willing to seek training opportunities to build their farm businesses and constantly update their knowledge to be more environmentally sustainable in their business, only about one-third agreed that they regularly attend SDSU’s Extension training workshops (see

Figure 3). However, unsurprisingly, looking at the source of information from which respondents receive information on new innovative ideas and training opportunities. Our descriptive statistics findings show that about 40% of respondents agree they receive information from private consultants and companies (e.g., agronomists) and about 39% from friends, family members, or neighbors. Therefore, limited information is shared with farmers regarding the training and workshop opportunities the SDSU Extension Program provides.

Bivariate Relationships

Precisely, age (interval level of measurement), level of education (ordinal level of measurement), and farm size (interval level of measurement) were used to test their correlation with the three scales (Entrepreneurial Scale, Networking Scale, and Training Scale). The Spearman's rank-order correlation (given the ordinal level of measurement for education) was computed to examine the relationship between participants' socio-demographic characteristics, including age, education level, and farm size, and the three entrepreneurial scales. We excluded gender as a socio-demographic characteristic in the analysis because of the small percentage of female respondents (2.7%).

As shown in

Table 2, we found statistically significant correlations between two socio-demographic characteristics of farmers (age and farm size) and some of the scales. There was a weak negative correlation between age and the entrepreneurial scale, indicating that as age goes up, entrepreneurial aspirations go down. Weak positive relationships were observed between farm size and the three scales. Hence, farmers with larger operations are more likely to have entrepreneurial aspirations, engage in networking, and seek training opportunities to build their entrepreneurial skills. Overall, we found no strong relationships between the socio-demographic characteristics of farmers and the three scales. However, results show moderate positive correlations between Entrepreneurial Scale and Training Scale, between the Networking Scale and Training Scale, and the Entrepreneurial Scale and Networking Scale that were all statistically significant. Thus, when producers agreed with one scale, they were more likely to agree with the others.

T-test Results

Two-tailed t-tests were performed to test whether there is a statistical difference of means based on age and education regarding farmers' entrepreneurial thinking and aspirations. For instance, a t-test was used to analyze the difference of means between younger and older farmers and another between farmers with a college degree versus those without a college degree. Entrepreneurial Scale, Networking Scale, and Training Scale were used as dependent variables, and two nominal variables, age (20-59 and 60+) and education (college degree, no college degree), as independent variables. The results show that younger farmers (age 59 and below) score significantly higher on the Entrepreneurial Scale than those who are older (60+) (see

Table 3). However, there was no significant difference between younger and older farmers on the Networking Scale or the Training Scale.

There were no significant differences in the Entrepreneurial Scale, Networking Scale, or Training Scale by college degree (see

Table 4). We also found no significant difference in the two-sample t-test results comparing entrepreneurialism scales by education.

ANOVA Results

We used a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine whether there were any statistically significant differences between the three entrepreneurialism scales by farm size. We used the three scales as dependent variables at the interval level of measurement, which are suitable for calculating mean variances. The three farm size groups (small farms, large farms, and very large farms) are considered ordinal and are used as independent variables. The differences between means of the three farm size groups on entrepreneurialism (13.6 small farms, 14.1 large farms, 14.8 very large sizes), networking (7.2 small farms, 7.4 large farms, 7.9 very large farms), and training (5.5 small farms, 5.8 large farms, 6.2 very large farms) are statistically significant (see

Table 5). In other words, farm size is related to farmers' adoption of entrepreneurism, willingness to build and use social networks to increase their income and profit, and tendency to seek training opportunities to develop their entrepreneurial skills and competencies. However, looking at the pairs in the results of multiple comparisons (not shown in the table), we find some insignificant differences between some pairings. For instance, the difference of means between small and large farms and large and very large farms on entrepreneurialism was not statistically significant. In addition, the difference of means between pairs of small and large farms on networking and between pairs of large and very large farms and small and very large farms on training was insignificant.

Multivariate Analysis Results

We also used multiple regression analysis to examine the simultaneous role of education, farm size, age, and the remaining two scales as predictor variables in each outcome variable (Entrepreneurialism Scale (Model 1), Network Scale (Model 2), and Training Scale (Model 3). This process allows us to examine which variable in a set of predictor variables best explains changes in the outcome variable holding the effects of other predictor variables controlled. We checked that all assumptions were met in each of the three models we ran. In Model 1, we used Entrepreneurship Scale as a dependent variable. R2 shows that the five predictor variables explain 57% of the total variability in the dependent variable. In Model 2, we used the same predictor variables and Network Scale as a dependent variable. Adjusted R2 shows that our predictor variables explain 52% of the total change in the dependent variable. In Model 3, we ran the same predictor variables and Training Scale as a dependent variable, and the adjusted R2 shows that predictor variables explain 60% of the variability in the dependent variable.

In Model 1, we find that education, age, networking, and training are all significant predictors of entrepreneurialism, mainly in the direction expected, after holding other variables constant. Surprisingly, as education increased in the model, entrepreneurialism decreased. In Model 2, we only find that entrepreneurialism and training are significant predictors of networking in the direction expected, holding other variables constant. Finally, in Model 3, we find that education, farm size, age, entrepreneurialism, and networking are all significant predictors of training in the direction expected after holding the other variables constant. In summary, our findings of multiple regression support some of our bivariate analysis findings but not all. For instance, while our bivariate analysis results show no strong correlations between age and the three scales, our multiple regression results indicate that age predicts entrepreneurialism and training significantly. In addition, while our two-sample t-test results show that education (means of college degree vs. no college degree compared) does not significantly affect the three scales, our multiple regression results indicate that education significantly predicts both entrepreneurialism and training. Finally, our bivariate and multivariate analysis results show that all three scales positively affect each other.

Discussion

This study examined whether SD farmers have entrepreneurial aspirations and motivations that can help them achieve agricultural sustainability. The sample represents commodity crop producers east of the Missouri River, where most SD commodity crops (e.g., corn and soybean) are produced. Since the findings represent a randomly selected sample of farmers drawn from a sampling frame primarily representing farm operations in eastern South Dakota, the findings can be generalized to the population of farmers in this model system.

Although our correlation, ANOVA, and Multiple Regression results vary, most of our findings support the hypothesis that SD commodity crop farmers think and act entrepreneurially but differ based on age, education, and farm size. Many crop producers seek new and innovative ways to increase their business and are dedicated to protecting their farmland from increased weather variability. Moreover, most participants asserted that they pay close attention to funding opportunities that can help them expand and meet the financial demands of their businesses, thus remaining competitive in the global market. Farmers also reported that they are looking for ways to diversify their businesses. However, despite their intentions to adopt entrepreneurialism, most farmers have no written business plans for their farm operations. Scholars argue that to be entrepreneurially successful, farmers need to have written business plans as part of strategic planning and to engage in training programs that focus on the development of their professional, managerial, and entrepreneurial skills [

28,

53].

Research has indicated that attending demonstration sites of field days can lead to conservation practice uptake [

54]. Although most study participants indicated they constantly seek training opportunities and update their knowledge and skills to ensure their businesses remain environmentally sustainable, the study shows that only about one-third regularly attend XXXX Extension training workshops

1. This factor may be due to the need for more information about the availability of training programs and activities focusing on developing farmers' entrepreneurial skills. Alternatively, many farmers in our sample may live far from places where training opportunities are available, or they need to be made aware of XXXX Extension's involvement in some of the workshops they attend. Thus, an area that needs further examination might be the types and quality of training programs accessible to farmers other than the XXXX Extension workshops and the role that these play in influencing farmers' decision-making. Furthermore, respondents stated that they use their social networks to increase their awareness of funding opportunities and learn new innovative ideas.

The study also found that socio-demographic characteristics of farmers, such as age, education level, and farm size, are associated with farmers' adoption of entrepreneurship and networking and their involvement in training activities. For instance, the results show that younger farmers are more likely to have entrepreneurial aspirations and adopt an entrepreneurial culture in their farm operations because of their high innovativeness. This finding confirms the study of [

20], who argue that younger farmers are more innovative and can maintain high profitability. They are also more likely to invest in environmentally sound practices [

55]. Additionally, results of ANOVA tests (and multiple regression analysis for networking only) indicate that farmers who operate larger farms are more likely to adopt entrepreneurship, engage in networking, and seek training opportunities to build their entrepreneurial skills. Thus, it supports the study's hypothesis that larger farm operators are more able or interested in developing entrepreneurial skills.

Conclusions

The results provide limited and mixed findings regarding an association between education and farmers' attitudes toward entrepreneurialism, like other studies [

56,

57]. Although the results support the hypothesis that younger farmers are more likely to have entrepreneurial aspirations, we find mixed results regarding whether age influences farmers' attitudes and motivations to seek training opportunities, update their knowledge on entrepreneurial and managerial skills, and engage in social networking. Moreover, the results support the hypothesis that crop producers are simultaneously seeking ways to develop their businesses and protect the land they operate. However, there was no strong, moderate, or statistically significant correlation between the socio-demographic characteristics of farmers and the attitudes of farmers toward entrepreneurialism. Overall, the findings confirm that training and social networks relate to whether farmers adopt entrepreneurialism. However, farmers are more focused on building networks than participating in training programs the SDSU Extension program provides.

Farmers will likely need to broaden their perceptions about farm business and adopt an entrepreneurial culture in their farm practices to remain competitive in the current global market and maintain agricultural sustainability. This study contributes to the existing literature on agricultural entrepreneurship and the adoption and magnitude of innovation and opportunities in farm businesses. To our knowledge, it is the first study that examines the impact of training and networking on farmers' entrepreneurial motivations in the Midwestern United States region, if not the entire country. Furthermore, the study adds to the existing literature [

58] that when designing agriculture-related policies, policymakers must incorporate entrepreneurship and economic policies that support farm entrepreneurship toward achieving sustainable agriculture. They must also help farmers to increase and diversify their funding opportunities to remain competitive in the global market [

15,

19]. As evidence from the US, Malaysia, and some European countries (such as the Netherlands, Poland, Finland, Sweden, and the UK) indicates, training farmers and equipping them with entrepreneurial skills and enhancing their utilization of social networks and opportunities helps them to incorporate new innovations and adopt strategic planning and BMPs [

59].

Further research may help us understand the factors that underlie the lack of interest of commodity crop farmers to adopt strategic planning, such as having written business plans that include sustainable long-term goals, short-term decision-making towards the progress in production, and keeping records of their operations. Further research may also unveil the reason behind the lack of participation in Extension training workshops, which may help them build their entrepreneurial skills and competencies, and whether farmers benefit from Extension websites. However, asking about a wider variety of training opportunities would have likely yielded different results. Most importantly, future research may examine the effect of age on farmers' use of their social networks to learn more innovative ideas and seek training opportunities. Additionally, we believe it is crucial to examine the extent to which farmers plan to engage in crop diversification, crop rotation, or other off and on-farm diversification strategies to increase their profit, especially given that many farmers believe that there is limited profit in farming business today. Finally, conducting a comparative study to examine how, entrepreneurially, South Dakota farmers are different from other farmers in the country and worldwide would be helpful.

Author Contributions

Although the primary author has made the highest contribution to this study, all authors listed have made a significant contribution to this study. The primary author contributed to the study by bringing up the research topic and formulated research questions and hypotheses. The first and second author are both main contributors in conceptualization and literature review. Regarding the methodology, data collection and analysis, all authors have significantly contributed. The original draft was prepared by the first author, then shared with all authors for review and improvement. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We thank the South Dakota Corn Utilization Council for funding the project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The project with reference (IRB-1812009-EXP) has been approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) for the protection of human subjects through exedited review on December 13, 2018. The proposed activity was deemed to be no greater than minimal risk and congruent with expedited category numbers (6) and (7) outlined in 45 CFR 46, section 110. Any changes to the protocol or related documents must be approved by the IRB before implementation. “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of South Dakota State University (protocol code (6) and (7) outlined in 45 CFR 46, section 110).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all participants who took part in this stud, they have signed it and were informed about confidentiality of their information and their right to withdraw at any time or not to answer any questions should they decline to.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are from the 2018 South Dakota Community Crop Producer survey the authors conducted with funding from South Dakota Corn Utilization Council. The authors confirm that a set of raw data supporting the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon request. Due to ethical considerations, the authors removed any information that might disclose the identity of the respondents. A descriptive data summary of the data used in this study is publicly available on the South Dakota State University website under "2018 South Dakota Commodity Crop Producer Survey Results." Which can be accessed at

https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/sdfarmsurvey/9/ or https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=sdfarmsurvey. The authors confirm that the study results (e.g., figures and tables), and all data associated with the study, are entirely based on the 2018 South Dakota Commodity Crop Producer Survey dataset, analyzed using SPSS and STATA statistical software.

Acknowledgments

The study is part of a collaborative project between social and natural science researchers from South Dakota State University and the South Dakota Corn Utilization Council to examine South Dakota farmers' land management practices and attitudes to increase their economic and environmental sustainability. We thank South Dakota agricultural producers for their participation, and Emireth Cancino (a South Dakota State University undergraduate student) for assisting in conducting the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

We, the authors of the article "Entrepreneurial Aspirations of South Dakota Commodity Crop Producers," declare that this publication does not involve any conflict of interest. We know of no conflict of interest associated with this publication to disclose, and we acknowledge the contribution of any institutions and individuals who contributed to this research. Besides, we have cautiously considered, assessed, and avoided ethical issues throughout this research study.

| 1 |

Nonetheless, farmers might be attending other training programs provided by organizations such as the Natural Resource Conservation Services, the South Dakota Soil Health Coalition, or farm consultation agencies. They might also receive information from sources other than the SDSU Extension Program. |

References

- B. H. Baltensperger, "Farm Consolidation in the Northern and Central States of the Great Plains," Great Plains Quarterly, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 256-265, 1987.

- Barbieri, M. Edward and L. Butler, "Understanding the Nature and Extent of Farm and Ranch Diversification in North America," Rural Sociology, vol. 73, no. 2, p. 205–229, 2008. [CrossRef]

- T. Marsden and Sonnino, R, "Rural development and the regional state: Denying multifunctional agriculture in the UK," Rural Studies, vol. 24, p. 422–431, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Dimitri, Effland, A and Conklin, N, "The 20th Century Transformation of US Agriculture and Farm Polic," The United States Department of Agriculture, 2005.

- R. Condor, "Entrepreneurship in Agriculture: A Literature Review," International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, vol. 40, no. 4, p. 517–562, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Petrzelka and Korsching, P. F, "Farmers' Attitudes and Behavior Toward Sustainable," Agriculture. Environmental Education, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 38-58., 1996. [CrossRef]

- P. Robertson and Harwood, R. R, "Agriculture, Sustainable," Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, vol. 1, pp. 111-118, 2013.

- Y. Gadanakis, J. Campos-González and P. Jones, "Linking Entrepreneurship to Productivity: Using a Composite Indicator for Farm-Level Innovation in UK Agriculture with Secondary Data," Agriculture, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 2-23, 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. McElwee and Bosworth, G, "Exploring the Strategic Skills of Farmers across a Typology of Farm Diversification Approaches," Journal of Farm Management, vol. 13, no. 12, p. 819 – 838, 2010.

- N. Taragola, Marchand, F, Meul, M, Passel, S. V and Dessein, J, "Development of an Entrepreneur Scan as a Driving Force for Sustainable Farming," in World Conference on Entrepreneurship and Sustainability, Dublin, Ireland, 2014.

- C. S. L. Dias, Rodrigues, R. G and Ferreira, J. J, "What is New in the Research on Agricultural Entrepreneurship?," Rural Studies, vol. 65, p. 99–115, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Dotsiuk, "Entrepreneurship as a Basis for Sustainable Development of the Agricultural Sector of the Econom," Green, Blue & Digital Economy Journal, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 10–21, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Díaz-Pichardo, Cantú-González, C, López-Hernández, P and McElwee, G, "From Farmers to Entrepreneurs: The Importance of Associative Behavior," The Journal of Entrepreneurship, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 91–116, 2012.

- S. Shane, A General Theory of Entrepreneurship: The Individual-Opportunity Nexus (New Horizons in Entrepreneurship series), Edward Elgar Publishing, 2003, p. 8437–6382.

- G. McElwee, "A Taxonomy of Entrepreneurial Farmers," International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, vol. 6, no. 3, p. 465–478, 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. Walley, Custance, P and Smith, F, "Farm Diversification: A Resource Based Approach," Journal of Farm Management, vol. 14, no. 4, p. 275 – 290, 2011.

- W. Ellis, Ratanawaraha, A, Diskul, D and Chandrachai, A, "Entrepreneurship as a Mechanism for Agro-Innovation: Evidence from Doi Tung Development Project, Thailand," International Journal of Business and Social Science, vol. 3, no. 23, pp. 138-151, 2012.

- D. Kahan, "Entrepreneurship in Farming. Farm Management Extension Guide," The United Nations – Food and Agriculture Organization, 2013.

- L. S. Morgan, Marsden, T, Miele, M and Morley, A, "Agricultural Multifunctionality and Farmers' Entrepreneurial Skills: A Study of Tuscan and Welsh Farmers," Rural Studies, vol. 26, pp. 116-129, 2010. [CrossRef]

- W. Morris, Henley, A and Dowell, D, "Farm Diversification, Entrepreneurship, and Technology Adoption: Analysis of Upland Farmers in Wales," Rural Studies, vol. 53, p. 132–143, 2017.

- L. Wilson-Youlden and Bosworth, G. R. F, "Women tourism entrepreneurs and the survival of family farms in North East England," The Journal of Rural and Community Development, vol. 14, no. 3, p. 126–145, 2019.

- P. Wilson, N. Harper and R. Darling, "Explaining Variation in Farm and Farm Business Performance in Respect to Farmer Behavioral Segmentation Analysis: Implications for Land Use Policies," Land Use Policy, vol. 30, pp. 147-156, 2013.

- Henley, "Entrepreneurial Aspiration and Transition into Self-employment: Evidence from British Longitudinal Data.," Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 253- 280, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Kwong and Thompson, P, "The When and Why: Student Entrepreneurial Aspirations," Journal of Small Business Management, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 299-318, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Ulrich-Schad, J, Wang, T, Dunn, B.H, Bruggeman, S. A and Clay, D. E, "Grassland retention in the North America Midwest following periods of high commodity prices and climate variability," Soil Science Society of American Journal, vol. 83, pp. 1290-1298, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Saak, Wang, T, Kolady, D, Ulrich-Schad, J.D and Clay, D, "Duration of usage and farmer reported benefits of conservation tillage.," Soil and Water Conservation, vol. 76, no. 1, pp. 65-75, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Hansson, Ferguson, R, Olofsson, C and Rantamäki-Lahtinen, L, "Farmers' Motives for Diversifying their Farm Business – The Influence of Family," Rural Studies, vol. 32, p. 240–250, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Stanford-Billington, C and Cannon, A, "Do Farmers Adopt A Strategic Planning Approach to the Management of Their Businesses?," Journal of Farm Management, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 3–40, 2010.

- T. Rambo, "The Agrarian Transformation in Northeastern Thailand: A Review of Recent Research," Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 6, no. 2, p. 211–245, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Lovell, Shennan, C and Thuy, N.N, "Sustainable and conventional intensification: how gendered livelihoods influence farming practice adoption in the Vietnamese Mekong River Delta," Environment, Development, and Sustainability, vol. 23, p. 7089–7116, 2021.

- Amata, "The Use of Non-Conventional Feed Resources (NCFR) For Livestock Feeding in the Tropics: A Review," Journal of Global Biosciences, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 604-613, 2014.

- L. S. Prokopy, Floress, K, Arbuckle, J. G, Church, S.P, Eanes, F. R, Gao, Y, Gramig, B. M, Ranjan, P and Singh, A. S, "Adoption of agricultural conservation practices in the United States: Evidence from 35 years of quantitative literature," Soil and Water Conservation, vol. 74, no. 5, p. 520–534, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Shackleton, Masterson, V, Hebinck, P, Speranza, C. I, Spear, D and Tengö, M, "Livelihood and Landscape Change in Africa: Future Trajectories for Improved Well- Being under a Changing Climate," Land, vol. 8, no. 8, p. 114–121, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. McElwee, "Developing Entrepreneurial Skills of Farmers: A Literature Review of Entrepreneurship in Agriculture," University of London & The Commission of the European Community, 2005.

- Urban and Xaba, G, "Enterprise Skills and Performance: An Empirical Study of Smallholder Farmers in Kwa-Zulu Natal," Contemporary Management, vol. 13, p. 222 – 245, 2016.

- M. Emery and Flora, C, "Spiraling-Up: Mapping Community Transformation with Community Capitals Framework," Community Development, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 19-35, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, "The Influence of Social Networks on Agricultural Technology Adoption," Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 79, no. 6, pp. 101-116, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Baumgart-Getz, Prokopy, L. S and Floress, K, "Why Farmers Adopt Best Management Practice in the United States: A Meta-Analysis of the Adoption Literature," Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 96, pp. 17-25, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Laurwere, "The Role of Agricultural Entrepreneurship in Dutch Agriculture of Today," Agricultural Economics, vol. 33, p. 229–238, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Pannell, Marshall, G.R, Barr, N, Curtis, A, Vanclay, F and Wilkinson, R, "Understanding and Promoting Adoption of Conservation Practices by Rural Landholders," Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture, vol. 46, no. 11, p. 1407–1424, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Z. M. Makhbul and Hasun, F. M, "Entrepreneurial Success: An Exploratory Study among Entrepreneurs," International Journal of Business and Management, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 116-125, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition ed., 866 Third Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10022, NY: Free Press, A Division of Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc, 2003, p. 576.

- W. Dearing, "Applying Diffusion of Innovation Theory to Intervention Development," Research on Social Work Practice, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 503-218, 2009. [CrossRef]

- E. Quinn and Halfacre, A. C, "Place Matters: An Investigation of Farmers' Attachment to Their Land," Human Ecology Review, vol. 20, no. 2, p. 117–132, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Nielsen, "Passing on the Good Vibes: Entrepreneurs' Social Support," Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 1465–7503, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Lauwere, Enting, I, Vermeulen, P and Verhaar, K, "Modern Agricultural Entrepreneurship," in 13th Congress, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2002.

- P. M. Noordhuizen, van Egmond, M. J and Jorritsma, R, "Veterinary Advice for Entrepreneurial Dutch Dairy Farmers – From Curative Practice to Coach-Consultant: What Needs to be Changed?," Tijdschrift voor Diergeneeskunde, vol. 133, no. 1, pp. 1-8, 2008.

- Dickes and Robinson, K. L, "An Institutional Perspective of Rural Entrepreneurship," American Journal of Entrepreneurship, vol. 7, no. 2, p. 44–57, 2014.

- G. A. Alsos, Carter, S, Ljunggren, E and Welter, W, Researching Entrepreneurship in Agriculture and Rural Development. The Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship in Agriculture and Rural Development, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2011.

- J. L. Steiner, Briske, D. D and Brown, D. P, "Vulnerability of Southern Plains agriculture to climate change," Climatic Change, vol. 146, p. 201–218, 2017. [CrossRef]

- National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), "2021 U.S. Billion-dollar Weather and Climate Disasters in Historical Context - Hazard and Socioeconomic Risk Mapping," National Oceanic and Atmospheric Adminstration (NOAA), 2021.

- Dillman, Smyth, J. D and Christian, L. M, Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th ed., Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2014, p. 528.

- V. W. Tassell and Keller, L. H, "Farmers' Decision-Making: Perceptions of the Importance, Uncertainty, and Controllability of Selected Factors," Agribusiness, vol. 7, no. 6, p. 523–535, 1991. [CrossRef]

- S. Singh, B. MacGowan, J. D. Ulrich-Schad, M. Dunn, H. Klotz and L. Prokopy, "The Influence of Demonstration Sites and Field Days on Conservation Practices Adoption," Soil and Water Conservation, vol. 73, no. 3, p. 274–281, 2018.

- Mozzato, P. Gatto, E. Defrancesco, L. Bortolini, F. Pirotti, E. Pisani and L. Sartori, "The Role of Factors Affecting the Adoption of Environmentally Friendly Farming Practices: Can Geographical Context and Time Explain the Differences," Sustainability, vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 1-23, 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. D. (. Rosairo HR, "A study on entrepreneurial attitudes of upcountry vegetable farmers in Sri Lanka," Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 39–58, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Chan, B. Sipes and T. S. Lee, Eds., Enabling Agri-entrepreneurship and Innovation: Empirical Evidence and Solutions for Conflict Regions and Transitioning Economies, Boston, Massachusetts: CABI International, 2017.

- Flemsæter, H. Bjørkhaug and J. Brobakk, "Farmers as Climate Citizens," Environmental Planning and Management, vol. 61, no. 12, pp. 2050-2066, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Rezai, Z. Mohamed and M. N. Shamsudin, "Informal Education and Developing Entrepreneurial Skills among Farmers in Malaysia," International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, vol. 5, no. 7, pp. 906-913, 2011.

- Barbieri, Edward, M and Butler, L, "Understanding the Nature and Extent of Farm and Ranch Diversification in North America.,," Rural Sociology, vol. 73, no. 2, p. 205–229, 2008. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).