Submitted:

15 June 2024

Posted:

17 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

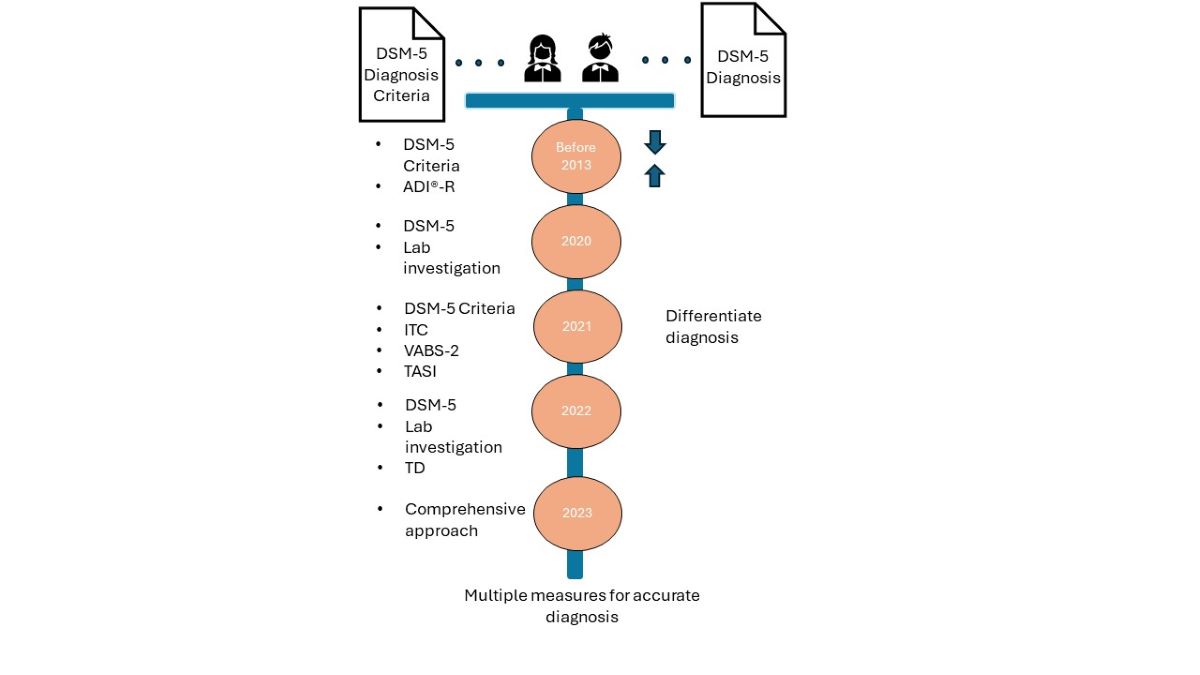

3.1. Pre-Publication Investigations of DSM-5 Symptom Categories

3.1.1. Fewer Toddlers Diagnosed with DSM-5

3.2. Post-Publication of DSM-5 Diagnoses of ASD

3.2.1. 2020 Screening Procedures Including the DSM-5 Standard

3.2.2. 2021 ASD Diagnosis Based of DSM-5 and Screening Tools

3.2.3. 2022 ASD Diagnosis Advanced on the Basis of Biomarker

3.2.4. 2023 ASD Diagnosis Requires Behavior, Neurological, and Biological Measures

4. Discussion

| Dominate Paradigm - Diagnostic Paradigm for ASD The Functionalist Paradigm [21] |

New Paradigm - Transdiagnosis Paradigm for ASD The Interpretivist Paradigm [21] |

|---|---|

|

|

5. Future Study and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, T.; Lund, B.; Dow, M. Do hospitals satisfy our healthcare information needs for rare diseases? Comparison of healthcare information provided by hospitals with information needs of family caregivers. Health Commun 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Lund, B.; Dow, M. Improving Health Information for Rare Disease Patients and Caregivers: A Survey of Preferences for Health Information Seeking Channels and Formats. J Hosp Librarian 2023, 2, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. Wang, T. Rare disease, rare information: Investigating healthcare information use in online global disability support groups. Doctoral Dissertation, Emporia State University, Emporia, KS, USA, May 13<sup>th</sup>, 2022.

- Wang, T.; Lund, B. Categories of information need expressed by parents of individuals with rare disorders in a Facebook community group: A case study with implications for information professionals. J Consum Health Internet 2020, 1, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition (DSM-III); American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease and Prevention. Data & Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/autism/data-research/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html(assessed on 6 June 2024).

- McCarty, P. , & Frye, R. E. Early detection and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: Why is it so difficult? Semin Pediatr Neurol 2020, 35, 100831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 8. American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, W: American Psychiatric Press, 1980.

- Cakir J, Frye RE, Walker SJ. The lifetime social cost of autism: 1990–2029. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2020, 72, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgleish T, Black M, Johnston D, Bevan A. Transdiagnostic approaches to mental health problems: Current status and future directions. J Consult Clin Psychol 2020, 88, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scimago Journal & Country Rank. About us. Available online: https://www.scimagojr.com/aboutus.php(assessed on 6 June 2024).

- Rosen NE, Lord C, Volkmar FR. The diagnosis of autism: From Kanner to DSM-III to DSM-5. J Autism Dev Disord 2021, 51, 4253–4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton ML, Robins DL, Jashar D, Brennan L, Fein D. Sensitivity and specificity of proposed DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorder in toddlers. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013, 43, 5–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 14. Coulter KL, Barton ML, Robins DL, Stone WL, Fein DA. DSM-5 symptom expression in toddlers. Autism, 1653; 202, 25, 6, 1653-1665. [CrossRef]

- Wetherby AM, Prizant BM. Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales: Developmental Profile. Paul H. Brookes Publishing: Towson, MD, USA, 2002.

- Mullen, EM. Mullen Scales of Early Learning Manual. American Guidance Service, Inc: Circle Pines, MN, 1995.

- Wiggins LD, Robins DL, Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Henrich CC. Support for a dimensional view of autism spectrum disorders in toddlers. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012, 42, 2–191. [Google Scholar]

- Khan ZUN, Chand P, Majid H, et al. Urinary metabolomics using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry: potential biomarkers for autism spectrum disorder. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Alrehaili RA, ElKady RM, Alrehaili JA, et al. Exploring early childhood autism spectrum disorders: A comprehensive review of diagnostic approaches in young children. Cureus. 2023, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, TS. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 4th ed. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996.

- Burrell G, Morgan G. Sociological Paradigms and Organizational Analysis: Elements of the Sociology of Corporate Life. Routledge: New York, NY, 1979, 2016.

- Sidhu N, Srinivasraghavan J. Ethics and medical practice: Why psychiatry is unique. Indian J Psychiatry. 2016, 58 (Suppl 2), S199–S202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Article Title | Journal Subject Area | Findings in Current Research |

|---|---|---|

| McCarty, P., & Frye, R. E. (2020, October). Early detection and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: Why is it so difficult?. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology, 35, 100831. | Pediatrics, Neurology | Improved training may increase the occurrence of practice by primary care physicians in ASD diagnosis. |

| Kaba, D., & Soykan Aysev, A. (2020). Evaluation of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Early Childhood According to the DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi, 31(2). |

Psychiatry and Mental Health |

Children under 7 is the riskiest DSM-5 period for lost diagnosis, which leads to progressive loss of functionality. |

| Harris, H. K., Sideridis, G. D., Barbaresi, W. J., & Harstad, E. (2020). Pathogenic yield of genetic testing in autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics, 146(4). | Pediatrics |

Toddlers with DSM-5 ASD diagnosis should be recommended for genetic testing. |

| Dow, D., Day, T. N., Kutta, T. J., Nottke, C., & Wetherby, A. M. (2020). Screening for autism spectrum disorder in a naturalistic home setting using the systematic observation of red flags (SORF) at 18–24 months. Autism Research, 13(1), 122-133. | Neurology, Genetics | ASD screening tools are not accurate enough in routine screening of toddlers. SORF provides beneficial video- recorded sample of child and family. |

| Hicks, S. D., Carpenter, R. L., Wagner, K. E., Pauley, R., Barros, M., Tierney-Aves, C., ... & Middleton, F. A. (2020). Saliva microRNA differentiates children with autism from peers with typical and atypical development. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(2), 296-308. | Psychiatry and Mental Health, Developmental and Educational Psychology |

Salivary microRNA is a noninvasive test that can improve accuracy in diagnosis of ASD in children. |

| Harris, H. K., Lee, C., Sideridis, G. D., Barbaresi, W. J., & Harstad, E. (2021). Identifying subgroups of toddlers with DSM-5 autism spectrum disorder based on core symptoms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1-15. | Developmental and Educational Psychology |

Social communication and restricted/repetitive behaviors may more precisely characterize subgroups within toddlers at time of ASD diagnosis |

| Kong, X. J., Sherman, H. T., Tian, R., Koh, M., Liu, S., Li, A. C., & Stone, W. S. (2021). Validation of rapid interactive screening test for autism in toddlers using autism diagnostic observation schedule™ second edition in children at high-risk for autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 737890. | Psychiatry and Mental Health |

Rapid Interactive screening Test for Autism in Toddlers (RITA-T) was found to be valid for screening toddlers at high risk of ASD allowing initiation of services before formal diagnosis with DSM-5. |

| Coulter, K. L., Barton, M. L., Robins, D. L., Stone, W. L., & Fein, D. A. (2021). DSM-5 symptom expression in toddlers. Autism, 25(6), 1653-1665. | Developmental and Educational Psychology |

Contradicts earlier studies suggesting that restrictive and repetitive behavior may not be apparent until later in childhood. |

| Pellecchia, M., Dickson, K. S., Vejnoska, S. F., & Stahmer, A. C. (2021). The autism spectrum: Diagnosis and epidemiology. In L. M. Glidden, L. Abbeduto, L. L. McIntyre, & M. J. Tassé (Eds.), APA handbook of intellectual and developmental disabilities: Foundations (pp. 207–237). American Psychological Association | Developmental and Educational Psychology |

Presents ASD as one of seven conditions that result in intellectual and developmental disabilities. Addresses intellectual disabilities from multiple disciplines in biological, behavioral, and social science. |

| Haffner, D. N., Bartram, L. R., Coury, D. L., Rice, C. E., Steingass, K. J., Moore-Clingenpeel, M., ... & Group, N. E. D. (2021). The Autism Detection in Early Childhood Tool: Level 2 autism spectrum disorder screening in a NICU Follow-up program. Infant Behavior and Development, 65, 101650. | Developmental and Educational Psychology |

Autism Detection in Early Childhood is useful as a level 1 screening tool identifying children at risk for ASD in high-risk NICU. |

| Khan, Z. U. N., Chand, P., Majid, H., Ahmed, S., Khan, A. H., Jamil, A., … & Jafri, L. (2022). Urinary metabolomics using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry: potential biomarkers for autism spectrum disorder. BMC Neurology, 22(1), 101. | Neurology | Urine organic acids profiles are good discriminators between children with ASD and typically developing children. |

| Alrehaili, R. A., ElKady, R. M., Alrehaili, J. A., & Alreefi, R. M. (2023). Exploring Early Childhood Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Comprehensive Review of Diagnostic Approaches in Young Children. Cureus, 15(12). | Medicine | Various diagnostic modalities, including lab investigations and neuroimaging, contribute to early detection and comprehensive assessment of ASD. |

| Saban-Bezalel, R., Avni, E., Ben-Itzchak, E., & Zachor, D. A. (2023). Relationship between Parental Concerns about Social–Emotional Reciprocity Deficits and Their Children’s Final ASD Diagnosis. Children, 10(11), 1786. | Pediatrics | Parental concerns about their child’s development regarding deficits in social-emotional reciprocity are significant in predicting a final diagnosis of ASD. |

| Lavi, R., & Stokes, M. A. (2023). Reliability and validity of the Autism Screen for Kids and Youth. Autism, 27(7), 1968-1982. |

Developmental and Educational Psychology |

When children outgrow early childhood, the Autism Screen for Kids and Youth with items related to DSM-5 criteria is a promising screening tool. |

| Francés, L., Ruiz, A., Soler, C. V., Francés, J., Caules, J., Hervás, A., ... & Quintero, J. (2023). Prevalence, comorbidities, and profiles of neurodevelopmental disorders according to the DSM-5-TR in children aged 6 years old in a European region. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1260747. | Psychiatry and Mental Health |

Neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD) often coexist with other disorders and it is rare for them to occur alone. There is evidence of presence of comorbidities in language disorders and ADHD. Low economic resources, lower levels of education of parents, and lifestyle habits that can be improved can alert clinicians to the possibility of NDD. |

| Journal Title | Journal Frequencies |

Journal Subject Area |

|---|---|---|

| Autism | 2 | Developmental and Educational Psychology |

| Frontiers in Psychiatry | 2 | Psychiatry and Mental Health |

| Seminars in Pediatric Neurology | 1 | Pediatrics, Neurology |

| Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi | 1 | Psychiatry and Mental Health |

| Pediatrics | 1 | Pediatrics |

| Autism Research | 1 | Neurology, Genetics |

| Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry | 1 | Psychiatry and Mental Health, Developmental and Educational Psychology |

| Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders | 1 | Developmental and Educational Psychology |

| Infant Behavior and Development | 1 | Developmental and Educational Psychology |

| BMC Neurology | 1 | Neurology |

| Children | 1 | Pediatrics |

| Cureus | 1 | Medicine |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).