Submitted:

17 June 2024

Posted:

18 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Physical Exercise

3.1. GAD

3.1.1. Physical Exercise as an Adjuvant to Pharmacotherapy

3.1.2. Yoga

3.2. SAD

3.2.1. Resistance and Aerobic Exercise

3.2.2. Yoga

3.3. PTSD

3.3.1. Resistance and Aerobic Exercise

3.3.2. Yoga

3.4. Panic Disorder

3.4.1. Resistance and Aerobic Exercise

3.4.2. Yoga

3.5. Conclusion

| Author, year of publication | Study design | Intervention | Participant count | Population characteristics | |

| Cox et al. (2000) |

Randomized controlled trial | Exercise on either a treadmill (jogging) or a stationary stepper (stepping) at either low intensity (50% predicted VO2 max) or high intensity (75% predicted VO2 max) for 30 minutes. | Total: 24 | -Male university students -Average age of 28.3 years -Engage in vigorous physical activity 3 times per week for 30–60 minutes -Recreational exercisers, not highly trained athletes |

|

| Mccarthy et al. (2017) |

Unblinded observational study with a waiting period and baseline control data collection | Trauma-sensitive yoga sessions are 90 minutes every seven days for eight weeks, consisting of Hatha yoga with various postures, sensory awareness, breath awareness, and guided meditation. Home practice was also encouraged. | Total: 30 | -Mean age of 63.5 years -The majority of participants were males -All participants had a diagnosis of PTSD -The majority of participants had relatively severe PTSD symptoms |

|

| Whitworth et al. (2019) |

Randomized controlled trial | The intervention included three 30-minute high-intensity resistance exercise sessions per week for 3 weeks, led by a certified personal trainer, with exercises tailored to the individual's eight-repetition maximum and limited interpersonal interaction. | Total: 30 | -Participants were non-treatment-seeking urban-dwelling adults The mean age of participants was 29.10 years -73.3% of the sample were female -Participants were aged between 18 and 45 years -Participants had exposure to a recent traumatic event within the past 2 years -Participants had a positive screen for PTSD and anxiety -Participants could not be undergoing any trauma-focused therapies at the time of the study -Participants on psychoactive medications for other conditions had to be on a stable dose for at least 6 months before the study |

|

| Ma et al. (2017) |

Randomized experimental design with purposive sampling | A home-based exercise program includes 30 minutes of exercise daily, 5 days per week for 3 months, a pocket-size book, a logbook, a DVD with exercise demonstrations, and regular communication with the research team. | Total: 86 | Among participants, 23 (27.8%) were diagnosed with OCD, 24 (28.9%) with panic disorder (PD), 4 (7.5%) with social phobia (SP), 2 (2.4%) with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 28 (33.7%) with GAD, and 2 (2.4%) with specific phobias. Participants reported a moderate-to-high level of anxiety, more than half were married, and those with OCD had more years of education and lower trait anxiety levels compared to other anxiety disorders. |

|

| Broman-Fulks et al. (2004) |

Randomized controlled trial | High-intensity aerobic exercise and low-intensity walking exercise, each completed for six 20-minute sessions over two weeks, with the high-intensity exercise aiming to achieve heart rates between 60% and 90% of the individual's age-adjusted predicted maximal heart rate. | Total: 54 | -Participants were 54 students, predominantly women (41 out of 54) -The age range of participants was 18-51, with a mean age of 21.17 -Participants had to achieve a score of 25 or more on the Anxiety Sensitivity Index, be at least 18 years old, and be in good general health to be included in the study -Exclusion criteria included health conditions that would prevent aerobic exercise, current involvement in psychotherapy or use of psychotropic medication, and current participation in an aerobic exercise program |

|

| Broman-Fulks et al. (2015) |

Randomized controlled trial | Participants received either aerobic or resistance training, which included two sets of each exercise to exhaustion with weights they could perform at least 10 repetitions and 2 minutes of rest between sets. | Total: 77 | -Female: 60% -Caucasian: 85% |

|

| Plag et al. (2020) |

Randomized controlled trial | High-intensity interval training (HIIT) every second day for 12 days and Lower-intensity exercise training (LIT) every second day for 12 days. | Total: 33 | -The study included 33 patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). -The sample consisted of 24 women and 9 men, with a higher percentage of women in the HIIT and LIT groups. |

|

| Lucibello et al. (2019) |

Randomized controlled trial | Nine-week moderate-intensity exercise group: 3 weekly exercise sessions involving cycling at 70-75% of HR maximum for 27.5 minutes each session. | Total: 54 | -Young adults aged 18-30 years old -Majority of female participants -Participants recruited from McMaster University -Participants engaged in no more than one hour of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per week for the past six months -The study focused on the effects of aerobic exercise training on physical performance and mental functioning |

|

| Ströhle et al. (2009) |

Crossover design, within-subject design | Treadmill walking for 30 minutes at 70% VO2 max and a bolus injection of CCK-4 (25 lg for patients, 50 lg for healthy subjects) dissolved in 2 ml 0.9% saline. | Total: 24 | -Patients with panic disorder and healthy age-and sex-matched control subjects | |

| Gaudlitz et al. (2015) |

Randomized, double-blind, controlled | -Exercise Group: Endurance training on a treadmill three times a week for 8 weeks for 30 minutes each time. -Control Group: Light exercises, light stretching, and simple yoga-based exercises three times a week for 8 weeks for 30 minutes each time. |

Total: 58 |

-Patients with panic disorder (PD) with or without agoraphobia -Aged between 18-70 -All patients were Caucasian -Exclusion of patients with severe mental disorders, acute suicidal tendencies, epilepsy, pregnancy, or breastfeeding |

|

| Wedekind et al. (2010) |

Randomized controlled trial | Paroxetine 20mg capsules daily for 10 weeks, Aerobic exercise for 45 minutes 3 times a week for 10 weeks, Relaxation training similar to Autogenic Training once daily for increasing durations up to 20 minutes by the end of the study. | Total: 75 |

Patients with panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, aged between 19 and 52 years on average, with a majority being female (70%) | |

| Herring et al. (2011) |

Randomized controlled trial | The study participants received interventions were Resistance Exercise Training (RET) and Aerobic Exercise Training (AET), both involving 2 weekly sessions for 6 weeks. RET sessions lasted approximately 46 minutes and 40 seconds, focusing on resistance exercises for the legs, while AET sessions consisted of 16 minutes of continuous leg cycling. | Total: 30 |

-Patients aged between 18-37 years -Patients with a primary DSM-IV diagnosis of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) |

|

| Yi et al.(2022) |

Randomized controlled trial | 12-week yoga intervention consisting of 6 45-minute sessions held once every 2 weeks | Total: 94 |

-Women with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following a motor vehicle accident (MVA) |

|

| Streeter et al. (2010) |

Randomized controlled trial | Yoga intervention (60-minute sessions 3 times a week for 12 weeks, taught by certified Iyengar yoga instructors with consistent presentation of weekly posture sequences) and Walking intervention (60-minute sessions 3 times a week for 12 weeks, matched for metabolic demands with the yoga intervention) | Total: 34 |

-Participants aged 18-45 years old with no current Axis I diagnosis -Nonpsychoactive medications were allowed if the dosage was stable for at least 1 month;- Individuals with recent yoga practice, active psychotherapy, certain medical conditions, recent medication affecting the GABA system, tobacco use, high alcohol consumption, and contraindications to MRI evaluation were excluded. -Women were obligated to use birth control and had to have negative pregnancy tests. |

|

| Javnbakht et al. (2009) |

Randomized controlled trial | Twice-weekly yoga classes of 90 minutes duration for two months, consisting of Ashtanga yoga exercises (Iyengar method) | Total: 34 |

-New female patient referrals without documented psychological disorders or specialist recommendation for yoga therapy -Exclusion of cases with a history of psychiatric disorders, drug abuse, and previous yoga practice |

|

| Jazaieri et al. (2012) |

Randomized controlled trial | The study participants received mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Aerobic Exercise (AE) interventions. MBSR included eight weekly 2.5-hour group classes, a 1-day meditation retreat, and daily home practice. AE included a 2-month gym membership with at least two individual AE sessions and one group AE session per week. | Total: 56 |

-Participants with Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) randomised to MBSR or AE: -52% female, -41% Caucasian, -mean age 32.8 Healthy control group: -52.1% female, -56.3% Caucasian, -mean age 33.9 Untreated group with generalised SAD: -44.8% female, -48.3% Caucasian, -mean age 32.3 |

|

| Fetzner et al. (2015) | Randomized controlled trial | Standardized aerobic exercise program on a stationary bicycle for six 20-minute sessions over two weeks at 60-80% heart rate reserve, supervised by certified personal trainers in a private laboratory exercise room. | Total: 33 |

- Participants were primarily women (76%) - Participants reported being Caucasian (79%), Canadian First Nations (9%), Asian (6%), and Latino (3%) - Participants were employed full-time (46%), students (24%), employed part-time (12%), on medical leave from their occupation (6%), or unemployed (6%) |

|

| Lundt et al. (2019) | Observational study with elements of randomization and control | Yoga therapy is provided in yoga classes, 60 minutes each, once a week for 8 weeks, including body and breathing activities and meditation. | Total: 70 |

The majority of the participants were women - All participants were of German nationality - 90% of the participants had secondary and higher education - The most common tumour diagnosis among participants was breast cancer - The average time since primary diagnosis was 24 months - A portion of the participants had experienced recurrence or were diagnosed with metastases |

|

| Gordon et al. (2020) | Randomized controlled trial | The intervention consisted of an eight-week RET program conducted twice weekly, with progressive resistance and various exercises. These included barbell squat, barbell bench press, hexagon bar deadlift, seated dumbbell shoulder lateral raise; barbell bent over rows, dumbbell lunges, seated dumbbell curls, and abdominal crunches. Participants also underwent a three-week familiarisation process before starting the whole intervention. | Total: 44 | - Participants meeting the criteria for AGAD - Participants not excluded if in treatment for anxiety, depression, or other mental health disorders |

|

| O'Sullivan et al. (2023) | Randomized controlled trial | Eight-week, twice-weekly resistance exercise training (RET) intervention including exercises such as barbell back squat, barbell bench press, hexagon bar deadlift, seated dumbbell shoulder lateral raise, barbell bent over rows, dumbbell lunges, seated dumbbell curls, and abdominal crunches. Sessions were one-on-one and lasted approximately 25 minutes. The resistance was progressively increased as participants completed two sets of 8-12 repetitions. Load adjustments were made based on performance. | Total: 55 | -36 female participants out of a total of 55 participants -Participants with and without subclinical Generalized Anxiety Disorder (AGAD) and Major Depressive Disorder (AMDD) -Participants recruited via posters, emails, and word of mouth -Participants stratified by sex and AGAD status -Participants not excluded for previous engagement in resistance exercise training -Participants were asked about their involvement in a formalized resistance exercise training program to quantify training age |

|

| Tully et al. (2015) | Observational study | Primary depression cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), Primary generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) CBT, Community exercise program once per week for 1 hour, including aerobic training, resistance training, and flexibility/balance exercises for 12 weeks | Total: 29 |

HF patients under psychiatric management with comorbid depression and generalized anxiety disorder | |

| Doria et al. (2015) | Non-controlled longitudinal study | SKY therapy for six months, including an intense workshop with 10 sessions over two weeks followed by weekly follow-up classes, consisting of five sequential breathing exercises with specific techniques like Ujjayi, Nadi Shodana, Kapalabati, Bhastrika, and Sudarshan Kriya. | Total: 69 | The population consisted of both men and women. -The majority of the participants were women. -The study included individuals with mental disorders, specifically anxiety and depression. |

|

| Simon et al. (2020) | Prospective randomized controlled trial | Kundalini yoga and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Generalized Anxiety Disorder, delivered in groups of 4 to 6 participants by 2 instructors during twelve 120-minute sessions with 20 minutes of daily homework. Kundalini yoga includes physical postures, breathing techniques, relaxation exercises, meditation, mindfulness practices, yoga theory, philosophy, and psychology. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy provides psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, progressive muscle relaxation, worry exposures, in vivo exposure exercises, and targeted metacognitions. | Total: 226 | -Participants were adults aged 18 years or older The majority of participants were female (69.9%) -Participants had a primary diagnosis of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) -Exclusions included various mental health conditions and a history of more than 5 yoga or CBT sessions in the past 5 years |

|

| Szuhany et al. (2022) | Randomized controlled trial | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for 12 weeks, Yoga (Kundalini Yoga) for 12 weeks, Stress education for 12 weeks | Total: 226 |

-Participants were 226 men and women - 70% of the participants were female - Exclusion criteria included various mental health conditions such as posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, eating disorders, etc. - Participants self-reported their age, gender, race, and ethnicity |

|

| Goldin et al. (2013) | Randomized controlled trial | Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and aerobic exercise (AE) stress reduction program for 8 weeks. MBSR included eight weekly 2.5-hour group classes, a 1-day meditation retreat, and daily home practice. AE included 2-month gym memberships requiring at least two individual AE sessions and one group AE session per week. | Total: 56 |

Participants with generalized Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) who met DSM-IV criteria for primary generalized SAD and had various comorbidities, including generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, specific phobia, dysthymia, panic disorder, agoraphobia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. | |

| Herring et al. (2015) | Randomized controlled trial | Resistance exercise training (RET) and aerobic exercise training (AET) were conducted twice weekly for six weeks. | Total: 26 | - Sedentary women - Diagnosed with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) - Young adults with insufficient sleep and irregular sleep patterns |

|

| Herring et al. (2011) | Randomized controlled trial | Resistance Exercise Training (RET) involves lower-body weightlifting with two weekly sessions, and Aerobic Exercise Training (AET) involves dynamic leg cycling with two weekly sessions. | Total: 30 |

-Primary diagnosis of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) -Not undergoing concurrent psychiatric or psychological therapy other than medication -Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS-IV) clinician severity rating of at least 4 |

|

| Rosenbaum et al. (2014) | Randomized controlled trial | Three 30-minute resistance-training sessions per week, pedometer-based walking program, weekly supervised exercise sessions, two unsupervised home-based exercise sessions, individualized exercise intensity, increase in load based on RPE, provision of pedometer and exercise diary, adjustments based on physical activity levels and PTSD symptom severity, designed concerning ACSM guidelines. Usual care involves psychotherapy, pharmaceutical interventions, and group therapy. | Total: 81 |

-84% of the participants were male -Mean baseline BMI was 30.5, with the majority of participants being overweight or obese |

|

| Jazaieri et al. (2016) | Randomized controlled trial | The study participants received Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for 8 weeks and Aerobic exercise (AE) for 8 weeks, including specific components for each intervention. | Total: 47 |

- 53% females - Predominantly Caucasian (45%) and Asian (45%) - Diagnosed with generalized social anxiety disorder |

|

| Fetzner et al. (2014) | Randomized controlled trial | A 2-week intervention involving six 20-minute aerobic exercise sessions on a stationary bicycle at 60-80% heart rate reserve, supervised by certified personal trainers. Participants were divided into three groups: one receiving interoceptive prompts (IP), another a distraction task, and the third with no specific prompts or distractions during exercise. | Total: 33 |

-Participants were primarily women (76%) -Participants reported being Caucasian (79%), Canadian First Nations (9%), Asian (6%), and Latino (3%) -Participants were employed full-time (46%), students (24%), employed part-time (12%), on medical leave from their occupation (6%), or unemployed (6%) |

|

| Javed et al. (2022) | case report | Yoga Practice Module (Pranayam, asanas, suryatrataka, OM kara meditation) for 30 minutes daily in the early morning at home; Dietary recommendations emphasizing specific food choices and preparation guidelines. | 1 | -32 years old, married male -Symptoms started at the age of 12 -No history of psychological trauma -Had caring parents and was a good performer in school |

|

| Broocks et al. (1998) | Randomized controlled trial | The intervention(s) that the study participants received were regular aerobic exercise (running) and clomipramine (112.5 mg/day) for a 10-week treatment protocol. | Total: 46 |

Patients with moderate to severe panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, outpatients, patients with no concomitant physical disorders or current substance abuse, and patients required to discontinue psychotropic medication at least 3 weeks before baseline. Young patients with no contraindications for aerobic or other forms of exercise. | |

| Carter et al. (2013) | Randomized controlled trial | Sudarshan Kriya Yoga (SKY) intervention is adapted for veterans and includes cyclical breathing at different rates, joint mobility exercises, warrior values, mild yoga stretches, Yoga Nidra, and guided meditation. Participants were encouraged to maintain a daily 30-minute yoga breath practice | Total: 25 | -The study population consists of male -Vietnam veterans - The average age of the participants is 58 years - The participants are classified as disabled due to service-related PTSD |

|

| Martin et al. (2016) | Randomized controlled trial | Participants received a 75-minute yoga intervention weekly for 12 weeks or twice weekly for 6 weeks, designed by a licensed psychologist and a certified Kripalu yoga instructor. The intervention included trauma-sensitive elements, simple poses progressing over time, and components of Dialectical Behavior Therapy. | Total: 38 |

-Female participants The majority of participants were white (52.6%) -Nearly half of the participants had previously taken a yoga class -Average body mass index was in the overweight range |

|

| Sree et al. (2024) | Randomized controlled trial | Integrated yoga sessions lasting 60 minutes, five days a week, for 12 weeks, including loosening exercises, sun salutations, physical postures, breathing practices, and anapana meditation. | Total: 64 |

Individuals diagnosed with panic disorder, gender distribution with 54.7% male and 45.3% female participants, majority of participants were literate, predominantly from semi-urban areas, majority of participants were unmarried, about 45.3% of participants were employed | |

| Vorkapic et al. (2014) | Randomized controlled trial | Group 1 (G1-Yoga): Yoga classes twice a week, 50 minutes each, for 2 months. Group 2 (G2-CBT + Yoga): Yoga practice and CBT sessions twice a week, 100 minutes (yoga once a week for 50 minutes, CBT once a week for 50 minutes), for 2 months. | Total: 20 |

-Both male and female participants -Diagnosed with panic disorder (DSM IV), with or without agoraphobia -Exclusion criteria: severe pulmonary disease, heart condition, high blood pressure -Inclusion criteria: subjects with depression (comorbidity) or using antidepressant or anxiolytic drugs |

|

| Huberty et al. (2020) | randomized feasibility trial | Intervention low dose (LD): 60 minutes per week of online yoga for 12 weeks. Intervention moderate dose (MD): 150 minutes weekly online yoga for 12 weeks. Stretch and tone control group (STC): 60 minutes weekly of online stretching/toning exercises for 12 weeks. |

Total: 90 |

-Participants were predominantly White (86%) -Most participants earned $61,000 per year or more -A majority of participants were college-educated -The average gestational age at the time of stillbirth was 30 weeks |

|

| Ensari et al. (2019) | A randomized, counterbalanced, within-subjects design | Participants received a 40-minute session of guided yoga or a light stretching protocol. The yoga session included vinyasa style yoga, while the stretching protocol involved minimal movement. Peak RPE was assessed after the session. | Total: 18 | -The sample further had clinically meaningful levels of generalized anxiety symptoms, measured by the Spielberger Trait Anxiety Inventory(TAI). | |

| Van Der Kolk et al. (2014) | Randomized controlled trial | The intervention was a 10-week trauma-informed yoga program consisting of breathing exercises, postures, and mindfulness meditation, offered as a weekly 1-hour class. | Total: 101 |

-Women with chronic, treatment-resistant PTSD -Adult women -Participants from the United States -Relatively well-educated women -Employed women |

|

| Participant age | Summary | Limitations | Main findings | ||

| 20-36.6 years | The study explores the delayed anxiolytic effect of acute aerobic exercise, the impact of exercise intensity and mode on state anxiety, and the need for further research on factors influencing state anxiety reduction post-exercise. | -The study should have thoroughly investigated the exercise mode as a determinant of the anxiolytic effect. -The sample size of 24 male university students may limit the generalizability of the findings. -The study did not explore the impact of age and gender on the anxiolytic effect of exercise. -The indirect estimation of submaximal target intensities could have confounded the results. -The study suggests further research to explore additional factors influencing the anxiolytic effects of exercise. |

-The study demonstrated a delayed anxiolytic effect of an acute bout of exercise, with a reduction in state anxiety observed 30 and 60 minutes following the cessation of exercise. -The association between state anxiety and exercise mode was not supported, indicating that differences in exercise mode did not significantly impact state anxiety levels. -The association between state anxiety and exercise intensity was not supported, suggesting that exercising at 75% predicted VO2 max did not result in lower post-exercise state anxiety levels than 50% predicted VO2 max. |

||

| 63.5 years | Yoga as an adjuvant treatment shows significant benefits in reducing symptoms of combat-related PTSD and improving the quality of life for military veterans. | -Small number of subjects - Unblinded approach to the investigation -Limited generalizability to younger populations -Lack of data on between-session practice and long-term retention of benefits -Lack of follow-up data -Lack of a double-blind approach |

Yoga intervention led to significant improvements in psychometric assessments, with reduced PTSD symptoms and a majority of participants achieving PCL scores below the diagnostic cut-off point. | ||

| 18–45 years | The research explores the feasibility of a high-intensity resistance exercise intervention for reducing post-traumatic stress symptoms in non-treatment-seeking adults with PTSD and anxiety, finding the intervention to be feasible and potentially beneficial, with further research needed to confirm the results. | -Small sample size -Unblinded assessor may introduce bias -Reliance on self-report measures instead of diagnostic interviews -Lack of a delayed follow-up period to assess long-term effects |

-High-intensity resistance exercise intervention was feasible and well-tolerated, with significant beneficial effects on symptoms of avoidance, hyperarousal, sleep quality, and hazardous alcohol use. | ||

| 40.11 years (mean) | The study evaluated the effects of a home-based exercise program on anxiety levels and metabolic functions in patients with anxiety disorders in Taiwan, showing significant improvements in various indicators and suggesting positive effects on both mental and physical health. | -The 3-month duration of the follow-up test may not capture all long-term effects -Reliance on self-report instruments could limit data accuracy |

The HB exercise program improved body mass index, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, moderate exercise levels in the experimental group, and reduced state and trait anxiety levels. The program also positively impacted metabolic indicators and anxiety levels in Taiwanese adults with anxiety disorders. | ||

| 18–51 years | The study discusses the importance of anxiety sensitivity as a precursor to panic disorder. It also highlights the effectiveness of aerobic exercise as a treatment for anxiety disorders. It shows that high-intensity exercise leads to more rapid reductions in anxiety sensitivity compared to low-intensity exercise. | -Lack of assessment of participants' previous exercise experiences -Lack of assessment of perceptions of effort and physiological sensations experienced during exercise -Lack of assessment of changes in participants' exercise habits between post-treatment and follow-up -Limited generalizability due to strict selection criteria |

-Both high-intensity and low-intensity exercise reduced anxiety sensitivity, but high-intensity exercise led to more rapid reductions and had more treatment responders than low-intensity exercise. -High-intensity exercise was more effective in reducing fear of anxiety-related bodily sensations compared to low-intensity exercise. -The study highlights the potential of high-intensity aerobic exercise in reducing anxiety sensitivity and fear of anxiety-related sensations. |

||

| 19.19-20.12 mean years old in subgroup | The study discusses the prevalence of anxiety disorders, the benefits of physical exercise as an intervention for anxiety, and the effects of aerobic exercise and resistance training on anxiety sensitivity and CO2 reactivity. It also highlights the lack of observable effects on distress tolerance and discomfort intolerance. | -The study sample consisted of non-selected young adults, limiting the generalizability of the findings to at-risk or clinical populations. -The intensity of the exercise interventions was relatively homogenous and moderate, suggesting a need to explore the effects of a broader range of exercise intensities on anxiety vulnerability factors. -Further research is needed to investigate if resistance training exercises engaging larger muscle groups could have a more significant impact on anxiety sensitivity and other vulnerability factors. -Comparisons with other established treatments like CBT in varying dosages would provide insights into the efficacy of aerobic exercise and resistance training for anxiety-vulnerable populations. -Longitudinal studies of longer duration and follow-up studies are necessary to assess exercise interventions' long-term effects and durability on anxiety vulnerability factors. |

-Physical exercise is effective in reducing anxiety vulnerability factors like anxiety sensitivity (AS) and reactivity to CO2 challenges. -Both aerobic exercise and resistance training led to significant decreases in AS scores. -Aerobic exercise reduced reactivity to CO2 challenges more effectively than resistance training. -Neither exercise had observable effects on distress tolerance (DT) or discomfort intolerance (DI). |

||

| 41.03 years (mean) | The research demonstrates that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) is highly effective and fast-acting in treating generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), potentially complementing traditional treatment approaches. | -Small sample size -Lack of assessment of training-related exhaustion -Short follow-up period limits the ability to assess long-term efficacy |

-HIIT and LIT showed moderate to significant effects, with HIIT being about twice as effective as LIT. -HIIT was highly influential, fast-acting, and could complement first-line treatments for GAD. -Aerobic exercise was confirmed as a beneficial treatment option for GAD, showing significant effects on core symptoms and comorbid depression. |

||

| 18–30 years | The research examines the impact of exercise on state anxiety in young adults, highlighting the benefits of regular physical activity in managing stress. It focuses on the differences in anxiety reduction between high and low-anxious individuals through a nine-week exercise intervention. | -Predominantly female sample -Single-state anxiety measure post-exercise -Non-exercise control group -Lack of physiological data collection at each time point -Single measure of state anxiety change once per week The majority of participants were female. -Lack of measure of sedentary behaviour |

-The exercise group with high anxiety at baseline showed increased reductions in state anxiety following acute exercise as training progressed. In contrast, no significant training effects were observed for the exercise subgroup with low baseline anxiety. -Regular physical activity, particularly moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, was influential in managing state anxiety in young adults, with more significant reductions observed in individuals with higher levels of anxiety. |

||

| Patients: 31.9 years; Healthy control subjects: 30.8 years | The research demonstrates that a single bout of mild to moderate aerobic exercise has acute anti panic and anxiolytic effects, reducing panic attack frequency and CCK-4-induced symptoms in patients with panic disorder. This suggests a potential therapeutic application of exercise in managing panic disorder. | -The study did not investigate the duration of the protective effects of a single bout of exercise. -The study used a 30-minute exercise protocol, which may differ from longer durations used in other studies. -This study needed to fully characterise the optimum dosage (duration and intensity) and frequency of exercise treatment for panic disorder. |

-The study's main finding was that 30 minutes of mild to moderate aerobic exercise had an acute anti panic and anxiolytic activity, reducing panic attack frequency and CCK-4-induced symptoms. -The study suggests that a single exercise bout may be used in the treatment of panic disorder. -Further research is needed to determine the optimal dosage, duration, intensity, and exercise frequency for treating panic disorder. |

||

| 18–70 years | The research demonstrates that regular aerobic exercise provides an additional benefit to cognitive behavioural therapy in patients with panic disorder, leading to improved anxiety symptoms and increased effectiveness of treatment. | -Possible relaxation effects in the control group -Need for larger sample size and more sophisticated statistical strategies -Further research is needed to refine the design of the active control group |

Aerobic exercise had a significant anxiolytic effect and enhanced the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural therapy in individuals with panic disorder, suggesting it as a promising additional therapeutic option. | ||

| 19–52 years | The research discusses a randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of aerobic exercise combined with paroxetine to relaxation combined with paroxetine or placebo in the treatment of panic disorder. While paroxetine was superior to placebo, aerobic exercise did not show significant differences from relaxation training in most efficacy measures. The paper concludes that regular aerobic exercise may still be a valuable tool in the treatment of panic disorder, especially for patients who are unwilling to take medication. | -The study design did not allow for actual double-blind conditions regarding exercise and relaxation. -The study did not show exercise superior to the control group, contradicting previous findings. -The study did not compare exercise directly to other established treatments like SSRIs or CBT. -The study did not include patients with significant depression, limiting the generalizability of the findings. -The study had a small sample size, which may affect the generalizability of the results. -The study did not investigate the long-term effects of exercise on panic disorder. -The study did not explore the potential interaction effects between exercise and medication. -The study did not assess the impact of exercise on different subtypes of panic disorder. |

Patients in all treatment groups showed improvement in primary and secondary efficacy measures, with paroxetine treatment demonstrating significantly better improvement than placebo. Regular aerobic exercise was not superior to relaxation training, but it can still be a helpful tool in combination with cognitive behavioural therapies for panic disorder. | ||

| 18–39 years | The research presents a randomized controlled trial demonstrating that exercise training, particularly resistance exercise training, is a feasible and effective short-term treatment option for reducing worry symptoms and promoting remission in sedentary women diagnosed with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), suggesting the need for further research in this area. | -Small sample size -Short treatment duration -Predominantly young-adult sample -Need for more and better clinical trials -Encouragement for continued investigation of mechanisms explaining antianxiety effects of exercise |

Exercise training, especially resistance exercise training (RET), can reduce worry symptoms among GAD patients and lead to higher remission rates than a waitlist control. RET and aerobic exercise training (AET) showed moderate reductions in worry symptoms. | ||

| 40.8–42.1 years (mean) | The paper demonstrates that a 12-week yoga intervention can effectively reduce psychological distress and improve PTSD symptoms in women who have experienced motor vehicle accidents. | -Small sample size -Evaluation of only one type of yoga, which may not be the most beneficial -Reliance on self-report data, which can be influenced by patient expectations and biases |

-The yoga intervention significantly reduced PTSD symptoms, anxiety, and depression in women who survived motor vehicle accidents. -The study showed that yoga had a positive impact on reducing intrusion and avoidance symptoms in women with PTSD following MVA. -The results suggest that a 12-week yoga practice can effectively reduce psychological distress in women with PTSD following MVA. |

||

| 18–45 years | The study demonstrates that yoga is associated with more significant improvements in mood and anxiety compared to walking, with positive correlations between increased thalamic GABA levels and improved mood/anxiety, suggesting a potential role of GABA in mediating the effects of yoga on mood and anxiety, warranting further research. | -Small sample size in the yoga group -Lack of significant increase in thalamic GABA levels in the yoga group -Potential limitation due to the use of a single MRI scanner -Lack of baseline differences between experienced yoga practitioners and controls in a previous study -The study did not explore the long-term effects of yoga intervention -The study did not investigate the effects of different types of yoga interventions -The study did not consider the potential impact of individual differences in response to yoga interventions |

-Yoga intervention led to more significant improvements in mood and anxiety compared to walking exercise -Increased thalamic GABA levels were associated with improved mood and decreased anxiety -Positive correlation found between acute increases in thalamic GABA levels and improvements in mood/anxiety scales |

||

| 22–40 years | The study discusses the perception of yoga as a stress management tool for alleviating depression and anxiety disorders, evaluates the influence of yoga on relieving symptoms of depression and anxiety in women, and concludes that participation in a two-month yoga class can significantly reduce anxiety levels in women with anxiety disorders, highlighting the effectiveness of yoga in managing and reducing stress. | -Limited to a female population -Small sample sizes -Lack of particular practice in the control group -Short study duration -Lack of mixed-gender sample |

Yoga is effective in reducing state and trait anxiety in women and can be considered as a complementary or alternative therapy for anxiety disorders. The potential of yoga in treating anxiety in women is significant and could be an important therapeutic option. | ||

| 16.4 to 49.2 years old for study participants, 24.1 to 43.7 years old for healthy controls | The study compares the effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Aerobic Exercise (AE) in treating social anxiety disorder (SAD) in adults, finding both interventions to be equally effective in producing meaningful changes in symptoms and well-being. | -The study examined two alternative interventions for adults with SAD, and while they produced modest clinically significant changes, they did not reach the same level as traditional treatments. -The chronicity of SAD and the comparison to the untreated SAD group suggest that future research should continue to explore alternative interventions such as MBSR and AE for SAD. -Future research may benefit from examining the potential enhancement of treatment outcomes with a combination of MBSR and AE or the addition of MBSR or AE to traditional treatments for SAD. |

Both MBSR and AE were effective in reducing social anxiety and depression and increasing subjective well-being immediately post-intervention and at 3 months post-intervention. Participants in both interventions showed improvements in clinical symptoms and well-being compared to an untreated SAD group. | ||

| -Mean age of 36.9 years | The paper discusses the potential benefits of aerobic exercise for individuals with PTSD, highlights the need for further research to confirm these benefits, presents a study evaluating the effects of a brief aerobic exercise program on PTSD symptoms, and concludes that aerobic exercise may be a valuable adjunct to traditional psychotherapy for individuals with PTSD. | -Follow-up clinical interviews were not performed - Nearly half of the sample did not complete the monthly follow-up - Individuals with physical health conditions co-occurring with PTSD were excluded - Additional activity during the study was not controlled for - Study groups differed in fitness capacity - Absence of a nonactive control group |

-Regular aerobic exercise has mental health benefits for individuals with anxiety disorders and can reduce symptoms of PTSD. -Aerobic exercise was shown to significantly reduce PTSD symptoms over the treatment period and maintain these gains at one-month follow-up. -The study supports the clinical application of aerobic exercise for individuals with PTSD, indicating its potential as an adjunct to traditional psychotherapy protocols. |

||

| -The average age of the participants was 58 years, with a range from 24 to 80 years | The paper discusses the common symptoms of anxiety, depression, and fatigue in cancer patients and the potential of yoga therapy to alleviate these symptoms, emphasizing the need for further research to confirm the promising results. | -Based on an observational design -Causality cannot be attributed to yoga therapy -Small sample size -Elevated symptom levels not part of inclusion criteria -A high percentage of female participants -Generalizability limited by education levels -The therapy period may have been too short |

The main findings of the study include a significant reduction in symptoms of anxiety, depression, and fatigue six months after the end of yoga therapy compared to baseline. Additionally, most patients continued practicing yoga on their own, with many attributing benefits to helping with anxiety and concerns about the future. | ||

| - Young adults aged 18-40 | Ecologically valid resistance exercise training effectively improved AGAD status. It reduced worry and anxiety symptoms in young adults with elevated worry indicative of AGAD, suggesting it is a potential alternative or augmentation therapy for anxiety disorders. | -Small sample size -Lack of attention-matched control condition -Lack of follow-up assessment -Lack of time-matched control condition -Lack of anonymous clinical interviews assessing baseline AGAD status -Insufficient power for detecting small-to-moderate reductions in worry symptoms -Potential benefit from attention and social interaction in the RET intervention -Lack of exploration of sex-related response differences to RET and potential mediators/moderators of response -Lack of sustainability assessment for reductions in symptoms |

RET significantly improved AGAD status with a Number Needed to Treat (NNT) of 3 and led to significant reductions in worry and anxiety symptoms, supporting its efficacy as an alternative or augmentation therapy for anxiety disorders among young adults with AGAD. | ||

| 18-40 years | The article demonstrates the effectiveness of resistance exercise training in reducing depressive symptoms among young adults at risk for elevated depressive symptoms. The authors highlight RET as a promising treatment for mild or subclinical depression and as a potential intervention for individuals with clinically meaningful anxiety. | -Lack of an attention-control condition -Absence of post-intervention follow-ups -Need for long-term follow-ups to assess maintenance of depressive symptom reductions -Lack of control for the use of contraceptive medications -Unclear inter-individual variation in depressive symptom responses to RET -Small sample size for a pilot efficacy trial -Use of QIDS for diagnosing depression status in the AMDD sample -Uncertainty about the effect of RET on depressive symptoms among young adults with clinically meaningful MDD with or without comorbid GAD |

Resistance exercise training (RET) led to significant, clinically meaningful, and large-magnitude reductions in depressive symptoms among young adults, supporting RET as a promising treatment for mild depression, in alignment with WHO and ACSM guidelines. | ||

| 61.1 mean years old in Primary depression treatment group 57.6 mean years old in Primary GAD treatment group |

The article discusses the effective treatment of comorbid depression and generalized anxiety disorder in heart failure patients using cognitive behavioural therapy, exercise, and psychotropic medication, with significant improvements in symptoms observed. | -The study is an exploratory investigation not designed to prove treatment efficacy. -The use of anxiety questionnaires may have elicited more referrals for patients with comorbid GAD and depression. -The study may not reflect comorbidity rates in other earlier-stage CVD populations. -Depression and anxiety disorders are frequently under-recognized. -Treatment was not allocated according to a randomization process but based on consultation and patient preference. -The current HFSMP was only government-funded for one session per week. -Patients were excluded from the analyses if meeting the criteria for alcohol or substance abuse or personality disorders. -The sample size, low statistical power, width of standard deviations, and number of statistical analyses should be considered when interpreting the findings. |

-The primary GAD CBT group showed a significant reduction in PHQ symptoms compared to the primary depression CBT group. -Participation in the exercise program was associated with significantly reducing PHQ-somatic symptoms. -The primary GAD CBT group had a lower average number of cardiac hospital readmissions compared to the primary depression CBT group. |

||

| 25-64 years old | The paper discusses the efficacy of Sudarshan Kriya Yoga (SKY) in significantly reducing anxiety and depression scores in patients suffering from these disorders, with a focus on stable patients participating in the study. | -Need for replication on a more significant clinical sample in a controlled trial to further investigate the effectiveness of the SKY Protocol | -SKY therapy significantly reduces Anxiety and Depression scores, especially after the initial treatment, leading to a long plateau phase. -The study verified that SKY therapy in a controlled environment significantly reduces Anxiety and Depression levels in patients across different groups. -The reduction in scores is particularly evident after the initial intensive SKY treatment, followed by a gradual decrease towards null anxiety/depression scores. |

||

| 31.1 mean years old | The article discusses the commonality and impact of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), the need for alternative interventions like yoga, the efficacy of Kundalini yoga for GAD, and the superiority of CBT as a first-line treatment for GAD. | -Findings may not generalize to community settings -Results for Kundalini yoga may not apply to all yoga types -Mediation analysis did not examine lagged associations |

The study's main findings indicate that both Kundalini yoga and CBT were more effective than stress education for treating generalized anxiety disorder, with CBT being superior to Kundalini yoga. (confidence: 90) | ||

| 20-46 years old | The study explores the impact of treatment preferences for CBT or yoga on outcomes and engagement in patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder. | -predominantly White and well-educated sample, limiting generalizability -specific form of yoga used may not represent all types of yoga -differences in public perceptions of yoga versus structured class may have influenced results -inability to differentiate effects of preference versus intervention within subjects -suggestion for future use of doubly randomized preference control trials. |

-Both yoga and CBT were more effective than stress education in treating GAD, with CBT being more effective than yoga. Matching treatment preference did not significantly improve treatment outcomes, and dropout rates were higher for yoga compared to CBT. | ||

| 32.87 mean years old in MBSR group 32.88 mean years old in AE group |

The paper investigates the effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) in reducing emotional reactivity and enhancing emotion regulation in patients with social anxiety disorder (SAD) compared to aerobic exercise (AE). It uses functional magnetic resonance imaging to study the neural correlates of attention regulation of negative self-beliefs. | -The study is limited to a single emotion regulation strategy and one type of anxiety-inducing probe, suggesting a need to compare multiple methods for different probes in future studies. -The fixed order of only four autobiographical situations may limit the generalizability of the findings, indicating the potential benefit of using a random sequence of more diverse life situations in future research. -Future analyses should explore whether baseline behavioural and neural signals during emotion regulation can predict the optimal treatment for individuals, suggesting a need for moderator analysis. -Further investigation into the underlying mechanisms of how MBSR and AE work, including whether changes in brain responses predict long-term clinical outcomes, is recommended, indicating the importance of mediator analysis. |

-MBSR led to more significant reductions in negative emotion and increases in attention-related brain regions compared to AE. -MBSR was associated with decreased emotional reactivity and increased behavioural self-regulation and emotion regulation. -Greater meditation practice in MBSR was linked to enhanced brain responses in attention regions. |

||

| 18–37 years old | Short-term exercise training improves sleep outcomes among GAD patients, especially for RET and weekend sleep. The study suggests that exercise can be an effective nonpharmacologic therapy for improving sleep in individuals with GAD. | -Small sample size -Low exercise dose, particularly for aerobic exercise training -Reliance on self-report diary measure of sleep -Lack of objective measurement of sleep -Need for future studies to explore more intense exercise stimulus and dose-response relations with sleep |

Short-term exercise training improves sleep outcomes among GAD patients, especially for resistance exercise training (RET) and weekend sleep. Improved sleep may be associated with reduced clinical severity among GAD patients. Exercise, particularly resistance training, can lead to significant improvements in sleep initiation, continuity, and reductions in time spent in bed and hypersomnia among young women with GAD. | ||

| 18-37 years old | The paper demonstrates that short-term exercise training, including resistance exercise training, can improve signs and symptoms associated with GAD, particularly irritability, anxiety, low vigour, and pain, highlighting the potential of exercise as a feasible treatment option for GAD. Further research is needed to explore the efficacy of exercise training compared to other treatments for GAD. | -Small sample size -Limited generalizability -Focus only on sedentary women -Lack of long-term follow-up -Absence of investigation into underlying mechanisms -Lack of comparison with other treatments |

Both RET and AET resulted in improvements in signs and symptoms associated with GAD, with RET showing significant reductions in anxiety-tension and irritability and larger effect sizes for various symptoms compared to AET. | ||

| Participants aged from 23 to 73 years. |

The study demonstrates that a 12-week exercise program, in addition to usual care, significantly improves mental health outcomes and physical health measures in in-patients with primary PTSD, supporting the use of structured exercise as an augmentation strategy for PTSD treatment. | -The study did not record potential confounding factors like chronic pain or fibromyalgia. -Data on pharmacological therapy were not recorded, which is acknowledged as a limitation. -Difficulty in accurately recording medication usage due to changes in regimes. -Variability in supervised session attendance due to the geographical location of the hospital. -Poor rate of exercise diary completion limited the exploration of dose-response associations. |

-The exercise intervention significantly reduced PTSD symptoms compared to usual care. -The intervention group showed improvements in depressive symptoms, waist circumference, sleep quality, and sedentary time compared to the usual care group. -The study demonstrated that a 12-week exercise program, in addition to usual care, can lead to improvements in both mental health outcomes and physical health outcomes for in-patients with primary PTSD. |

||

| Age range: 23–53 years, mean age 33.3 years |

The article examines how pre-treatment social anxiety severity moderates the impact of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and aerobic exercise (AE) for generalized social anxiety disorder. The authors found that both interventions produced equivalent reductions in weekly social anxiety symptoms but were influenced by pre-treatment social anxiety severity levels. | -Small sample size for moderator analyses -Need for future studies with larger sample sizes to replicate and extend findings -Lack of examination of MBSR and AE within other anxiety disorders for generalizability -Lack of direct comparison of MBSR and AE to gold-standard treatments |

Pre-treatment social anxiety severity moderates the impact of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and aerobic exercise (AE) on social anxiety symptoms. MBSR is more effective for patients with lower pre-treatment social anxiety severity, while AE is more effective for patients with higher pre-treatment social anxiety severity. Tailoring treatment recommendations based on pre-treatment social anxiety severity could enhance intervention effectiveness. | ||

| mean age of 36.9 years | The article discusses the therapeutic effects of aerobic exercise for individuals with PTSD and related disorders, supporting its clinical application for improving mental health outcomes. | -Follow-up clinical interviews were not performed -Nearly half of the sample did not complete the monthly follow-up -Individuals with physical health conditions co-occurring with PTSD were excluded -Additional activity during the study was not controlled for -Study groups differed in fitness capacity -Absence of a nonactive control group |

Regular aerobic exercise has mental health benefits for individuals with anxiety disorders and can reduce symptoms of PTSD. Aerobic exercise was effective in reducing PTSD symptoms over the treatment period and maintaining these gains at one-month follow-up. The study supports the clinical application of aerobic exercise for individuals with PTSD stemming from various traumas. | ||

| 32 years old | The article presents a case report where a patient with social anxiety disorder and paruresis-specific social phobia showed significant improvement after practising yoga and meditation under supervision, highlighting the potential benefits of yoga in such cases. | -Single case report limits generalizability -Lack of control group -Self-reported symptoms may introduce bias -Long-term effects not explored -Need for more extensive controlled studies for validation |

-Yoga practices led to significant improvements in multiple parameters related to Social Anxiety Disorder and paruresis, as evidenced by reduced scores on various scales and improved quality of life. | ||

| age range 18–50 years | Regular aerobic exercise alone is associated with significant clinical improvement in patients who have panic disorder, but it is less effective than treatment with clomipramine. | The short duration of the study (10 weeks) may not be sufficient to fully evaluate the effects of exercise. -Lack of actual double-blind conditions due to the nature of comparing a behavioural treatment approach with medication intake -Possibility of nonspecific effects such as increased social interaction contributing to the beneficial effect of exercise -The study does not address the long-term effects or risk of relapse associated with regular exercise in panic disorder -The study does not explore potential subgroups of patients who may respond preferentially to exercise -The study does not investigate the combination of exercise and drug treatment to assess potential potentiating of treatment effects |

The main findings suggest that exercise and clomipramine were effective in treating panic disorder, with clomipramine being more effective than exercise. | ||

| 58 (average) years old | The article explores the potential benefits of Sudarshan Kriya Yoga (SKY) in reducing symptom severity in Vietnam veterans with treatment-resistant PTSD, indicating that yoga breath techniques may offer a valuable adjunctive treatment for this population. | -small sample size -lack of blinding -use of a wait-list control -difficulty in determining responsible components of the intervention -need for more extensive studies with more diverse populations -challenges in adapting and disseminating multi-component yoga programs to veterans -difficulty in maintaining improvements due to lack of participant commitment |

-The study showed significant reductions in PTSD symptoms in both the SKY Intervention group and the Control group at the 6-month follow-up, indicating the potential benefits of the yoga intervention for veterans with chronic PTSD. | ||

| 20-65 years | The article discusses the impact of a yoga intervention on physical activity, self-efficacy, and motivation in women with PTSD symptoms, highlighting the importance of understanding the psychological mechanisms behind physical activity behaviour change. It also highlights the potential benefits of yoga on mental health. | -The study focused on women with subthreshold or full PTSD, limiting its generalizability to men or other mental health populations. -The study had a small sample size, which may have limited the ability to detect significant changes in relevant constructs. -The purpose of the parent study was to investigate the effect of the yoga intervention on PTSD symptoms and not necessarily to promote continued physical activity in participants. -The study may have lacked statistical power to detect medium effect sizes. -The study should have addressed the utility of other forms of physical activity beyond yoga, such as flexibility and strength training. -The study suggested that future research should aim to better understand the growth of psychological determinants during and after a yoga intervention to develop more targeted interventions for individuals with mental health disorders |

-The yoga intervention did not lead to significant changes in physical activity or self-efficacy but resulted in a substantial decrease in external motivation. -While there was a trend towards increased leisure-time physical activity in the yoga group, it did not reach statistical significance. -The control group significantly decreased amotivation scores during the study. |

||

| 18-35 years old | The article provides compelling evidence that yoga can significantly improve anxiety symptoms and quality of life in individuals with panic disorder, offering a valuable complementary or alternative approach to traditional treatments. | -Participants were all diagnosed with panic disorder and recruited from a single location, limiting generalizability. -Further research with more extensive and diverse samples is needed to confirm the generalizability of the findings. -Lack of investigation into the specific mechanisms by which yoga reduces anxiety and improves quality of life. |

The yoga group exhibited a significant reduction in anxiety levels and improvements in quality of life compared to the control group, suggesting yoga is a valuable complementary or alternative approach to traditional treatments for anxiety disorders. | ||

| 18-60 years old | The study explores the therapeutic benefits of yoga in reducing panic-related symptoms in patients with panic disorder, both when practised alone and in combination with cognitive-behavioural therapy. | -Need for further research to explore the mechanisms through which mind-body practices improve mental health -Transparency regarding potential conflicts of interest |

The study demonstrated significant reductions in anxiety levels, panic-related beliefs, and panic-related body sensations in patients with panic disorder, with the combination of yoga and CBT showing more significant improvements compared to yoga alone. | ||

| ≥18 years of age | The study is a feasibility trial that aimed to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a 12-week home-based, online yoga intervention with varying doses for women who have experienced stillbirth. Results showed significant decreases in PTSD and depression and improvements in self-rated health at post-intervention. | -Inconsistencies with the software used to track participation -Sample not necessarily representative of the population of women who have had stillbirths in the US -High number of dropouts -The study was a feasibility study, and the sample size was not powered to determine the efficacy |

The study found significant decreases in PTSD and depression and improvements in self-rated health at post-intervention for both intervention groups, with the moderate dose group reporting the prescribed minutes of yoga to be too much. There was also a significant difference in depression scores and grief intensity between the moderate dose and control groups. | ||

| 22.1 mean years old | The study investigates the efficacy of yoga for improving cognitive and physical anxiety symptoms in high-anxious women, exploring the possible dissociation between mental and physical symptoms of anxiety among women with anxiety sensitivity. It also aims to assess the immediate and delayed anxiolytic effects of yoga in response to an anxiety-inducing CO2-inhalation task in women with high anxiety sensitivity. | -Small sample size -Control condition might not have been the most appropriate choice -Lack of comparison between individuals with high vs low AS |

-The study did not find significant differences between the effects of yoga and light stretching on anxiety symptoms. -Physical activity, regardless of the specific type, showed an overall reduction in cognitive anxiety symptoms. -The study suggests a dissociation between cognitive and physical symptoms of anxiety in women with anxiety sensitivity |

||

| 18-58 years old | The study demonstrates that a 10-week, weekly yoga program can significantly reduce PTSD symptoms in women with chronic treatment-resistant PTSD, highlighting the importance of body awareness and somatic regulation in the treatment of PTSD. | -Need for replication with different populations and in various cultural settings -Further investigation into the mechanisms of mindfulness meditation and their extension to yoga -Importance of dismantling the components of yoga to study their specific contributions |

Yoga significantly reduced PTSD symptomatology in women with chronic treatment-resistant PTSD, with effect sizes comparable to traditional psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic approaches. | ||

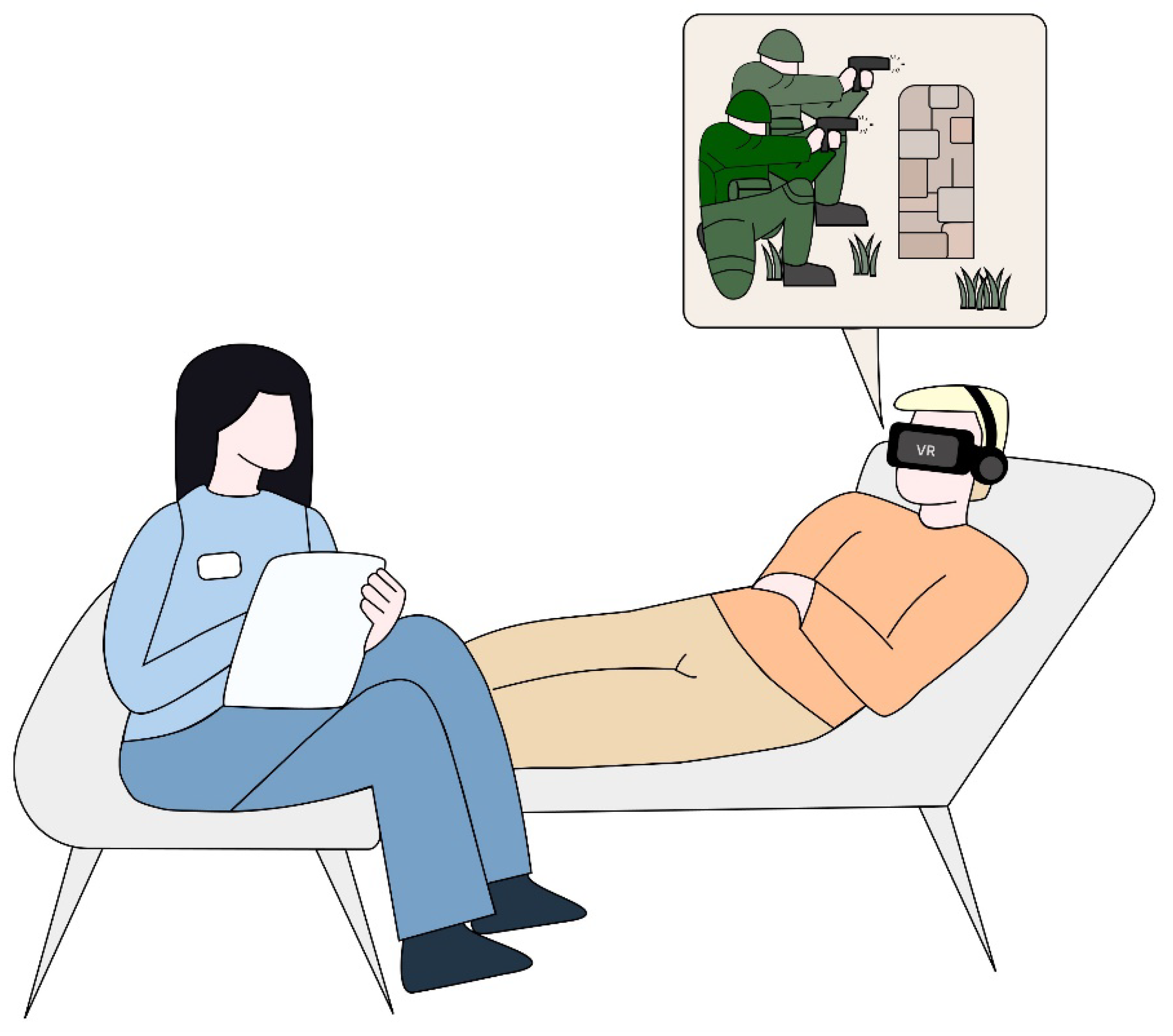

4. Virtual Reality (VR)

4.1. PTSD

4.2. SAD

4.3. GAD

4.4. Phobias

| Author, year of publication | Study design | Intervention | Participant count | Population characteristics |

| Mclay et al. (2014) |

Retrospective observational study, non-controlled, single-site | Virtual Reality Graded Exposure Therapy (VR-GET) consists of weekly to biweekly sessions with a psychologist, with a fixed number of sessions (5, 10, 15, or 20) in the open-label study and a fixed 10-week treatment duration in the randomized trial. The therapy included graded VR exposure, physiologic monitoring, and skills training. | Total: 28 | -Active-duty service members -Participants with PTSD related to service in Iraq or Afghanistan -Participants who completed neuropsychological testing and self-report measures of PTSD, depression, and generalised anxiety |

| Beidel et al. (2017) |

Randomized controlled trial | Trauma Management Therapy (TMT) with Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) was conducted three times per week for five weeks, followed by group treatment twice-weekly for the first two weeks and then once weekly, totalling 43.5 hours of treatment for each patient. The individual exposure therapy component of TMT used an intensive flooding approach. | Total: 92 |

-Iraq and Afghanistan veterans and active duty military personnel with combat-related PTSD |

| Anderson et al. (2013) |

Randomized controlled trial | Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRE) for 8 sessions with up to 120 minutes of exposure and Exposure Group Therapy (EGT) for 8 sessions with up to 120 minutes of exposure. | Total: 97 | Participants with social anxiety disorder, mostly women, ethnically diverse sample, the majority reported completing college, 43.2% reported an annual income of $50,000 or more, 43.2% reported being “married”, the majority did not have a comorbid diagnosis |

| Anderson et al. (2005) |

An open clinical trial with a treatment manual, homogenous inclusion/exclusion criteria, independent assessment, and a behavioural avoidance test | Cognitive-behavioural treatment using virtual reality for exposure therapy for eight sessions, including anxiety management training and exposure therapy using a virtual audience. | Total: 10 | -Predominantly female -Married -Well-educated -Middle-to-upper class -Self-identified as either Caucasian or African-American -Met criteria for social phobia or panic disorder with agoraphobia -Most participants met the criteria for another anxiety disorder |

| Bouchard et al. (2016) |

Randomized controlled trial | Individual CBT with exposure either in virtuo or in vivo for 14 weekly 60-minute sessions. Therapists were graduate students experienced in CBT for anxiety disorders. | Total: 59 |

-French-speaking individuals -Aged 18 to 65 years diagnosed with SAD according to DSM-5 criteria, excluding those with specific conditions or receiving concurrent psychotherapy. |

| Rubin et al. (2021) |

Randomized Controlled Trial | VRET with attention guidance training (AGT) -two 45-minute sessions over one week, including psychoeducation, public speaking exposures, and specific instructions to focus on audience members' faces with feedback on gaze behaviour. | Total: 21 |

-Participants were fluent in English -Participants had a Personal Report of Public Speaking Anxiety > 98 -Participants had a Leibowitz Social Anxiety Scale > 30 -Participants had a Peak fear ≥ 50 on the behavioural approach task during the baseline public speaking challenge -Participants met DSM-5 Criteria for Social Anxiety Disorder |

| Pitti et al. (2015) |

Randomized controlled trial | CBT for 11 sessions, Paroxetine at a mean dose of 22.60 mg/day, Virtual reality exposure for 4 sessions, in addition to CBT sessions | Total: 99 | -Patients with agoraphobia, mostly female -Mostly having agoraphobia with panic disorder The majority of patients were chronic cases. -Exclusion criteria included psychotic symptoms, bipolar disorders, high suicide risk, heart disease, neurological disease, or ophthalmologic disease |

| Kim et al. (2022) |

Randomized controlled trial | Eight sessions of virtual reality self-training (VRS) over 2 weeks in three different environments with increasing difficulty levels. | Total: 52 |

Participants were diagnosed with SAD according to DSM-5 criteria, with a Liebowitz social anxiety scale-self report (LSAS) score of more than 30. |

| Zainal et al. (2021) |

Randomized controlled trial | Self-guided VRE for social anxiety disorder, including exposure scenarios related to an informal dinner party and a formal job interview, with increasing levels of anxiety-inducing situations, along with between-session in vivo exposure therapy homework. The VRE included a virtual therapist, SUDS ratings, and cutting-edge technology. Sessions were held twice a week for 50–60 minutes each. | Total: 44 |

-Majority female (77.3%) -Diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds -Varied educational attainment |

| Malbos (2013) |

Randomized Controlled Trial | VRET alone for one group and VRET combined with cognitive therapy for another group. VRET sessions involved exposure to nine different virtual environments related to agoraphobic fears for 50–60 minutes each. Cognitive therapy for the combined group included psychoeducation, anxiety acceptance, cognitive restructuring, positive self-statements, and relapse prevention. Participants were instructed not to practice voluntary self-exposure between sessions. | Total: 19 |

-Participants were predominantly Caucasian -Mix of educational backgrounds -Most were married or in a de facto relationship, and most worked or studied full-time. -Some participants had co-morbid disorders such as major depression, social phobia, and specific phobia. |

| Powers et al. (2013) |

within-subjects incomplete repeated measures design with random starting order and rotation counterbalancing | Participants conversed with an actor/operator in either VR or in vivo environments. The VR conversation involved using a virtual environment through a stereovision head-mounted display (HMD) and noise-cancellation headphones. The facilitator used a microphone headset to speak with the participant. | Total: 26 |

-The study included 26 undergraduate participants, primarily females (73.1%). -The majority of participants were Non-Hispanic White (76.9%), with smaller percentages being Black (11.5%), Hispanic (7.7%), and Asian (3.8%). -Participants were recruited from an undergraduate psychology course and received extra credit for their participation. -Participants scored similarly to college students in previous studies on measures of social anxiety and general anxiety. |

| Wang et al. (2020) |

randomized controlled trial | Participants with GAD were randomly assigned to either a virtual nature (VN) or a virtual abstract painting (VAP) group. | Total: 77 | -Participants with GAD -Normal body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 and 24 kg/m2. |

| Wald et al. (2003) | Case study | Three sessions of VRET after a 7-day baseline | Total: 7 | - Seven adults with a specific phobia diagnosis, consisting of six females and one male, all possessing valid driver's licenses, reporting a longstanding history of driving fear and avoidance, with three participants having a history of being in a motor vehicle accident. |

| Kampmann et al. (2016) | Randomized controlled trial | Participants received VRET or iVET for ten 90-minute sessions scheduled twice weekly, without any homework assignments and with exposure elements based on protocols without cognitive components. | Total: 60 |

Participants diagnosed with social anxiety disorder, 63.3% women, were recruited through various sources; exclusion criteria included factors like recent psychotherapy for SAD, current use of certain medications, history of psychosis, current suicidal intentions, substance dependence, severe cognitive impairment, and insufficient command of the Dutch language. |

| Tortella-Feliu et al. (2010) | Randomized trial | Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET), Computer-aided exposure with a therapist (CAE-T), Self-administered computer-aided exposure (CAE-SA) | Total: 60 | -Diverse community-based sample -Participants with specific phobia related to fear of flying -Participants meeting DSM-IV criteria for specific phobia |

| Participant age | Summary | Limitations | Main findings | |

| 34.07 average years old | The study investigates the effectiveness of Virtual Reality Graded Exposure Therapy (VR-GET) on PTSD, depression, anxiety, and neuropsychological functioning, showing significant reductions in PTSD and anxiety severity and improvements on the emotional Stroop test, but no significant changes in depression or other neuropsychological measures. | -Participants were allowed to decline neuropsychological testing, potentially affecting the completeness of the data. -The small sample size may have limited the ability to detect relationships between PTSD and neuropsychological impairment consistently. -Larger studies are needed to determine the efficacy of the treatment modality in other areas. -The study suggests that VR-GET may be more effective for treating PTSD specifically. |

-VR-GET treatment led to significant reductions in PTSD and anxiety severity, along with improvements in the emotional Stroop test. -Changes in the emotional Stroop test did not correlate with changes in self-reported PTSD symptoms. -The study supports the use of VR-GET as a treatment for PTSD, indicating benefits may be focused on specific areas. |

|

| 37.67 mean years old in TMT group 33.26 mean years old in EXP group |

The article demonstrates the effectiveness of VRET in significantly reducing PTSD symptoms, with positive results maintained at the six-month follow-up. | -Dropout rate differences between TMT and EXP groups -Baseline differences despite randomization -Lack of comparison with different exposure models |

-VRET resulted in significant decreases in PTSD symptoms as assessed by the CAPS and PCL-M. -TMT, which includes VRET plus a group treatment for anger, depression, and social isolation, showed additional benefits in enhancing social and emotional functioning compared to VRET plus a psychoeducation control condition. -Both VRET and TMT led to significant decreases in depression and anger, with TMT specifically enhancing social functioning. Both interventions: -All treatment gains were maintained at the six-month follow-up. -42%-50% of each group demonstrated reliable and clinically significant changes in PTSD symptoms, with all but one participant showing at least reliable change. The relapse rate was meager at 4.5%. |

|

| 19-69 years old | The article compares VRET to exposure group therapy and a waitlist for social anxiety disorder, showing significant improvements in both active treatments compared to the wait list, with virtual reality exposure therapy being equally effective as exposure group therapy. | -Difficulty in equating two treatments delivered in different formats -Need for comparison with another individually administered treatment to equate factors -Challenge in comparing similar treatments delivered across different modalities -Limited generalizability due to specific inclusion criteria -Lower comorbidity rate in the sample compared to typical individuals with social anxiety disorder -Underrepresentation of ethnic/racial diversity in treatment efficacy research |

-Virtual reality exposure therapy effectively treats social fears and maintains improvement for at least 1 year. -Virtual reality exposure therapy is equally effective as exposure group therapy. -Virtual reality exposure therapy is effective for reducing symptoms of social anxiety disorder and public speaking fears, with changes in behavior observed in the real world. -Improvement in fear of negative evaluation was not immediate post-treatment but was observed at follow-up. -Both virtual reality exposure therapy and exposure group therapy showed similar improvements across various outcome measures and process variables. |

|

| not mentioned | The study discusses a study that used CBT with virtual reality (VR) for exposure therapy to treat public-speaking anxiety, showing significant improvement in self-report measures of public-speaking anxiety post-treatment and at follow-up. | -Should not include individuals whose primary diagnosis is panic disorder -The addition of physiological monitoring would improve the assessment -Future work could isolate the effect of VR on treatment response -Disadvantages include cost and the inability of the VR to match the idiosyncratic fears or elicit anxiety for some patients |

-Participants experienced significant reductions in public-speaking anxiety post-treatment, with maintained improvements at follow-up. -Most participants showed improvement in fear of public speaking measures and reported feeling significantly better and satisfied with the treatment. -Audience members rated participants as performing better and less anxious at post-treatment compared to pre-treatment. |

|

| 18–65 years old | The study discusses the advantages and effectiveness of using virtual reality in CBT for social anxiety disorder, highlighting the positive outcomes of CBT with virtual exposure compared to traditional CBT. | -Lack of clinical evaluations by independent assessors -Study focused on individual CBT, not group format -Need for replication with a larger sample -In vivo exposures did not precisely match in virtual scenarios |

-CBT with in virtual exposure and in vivo exposure showed improvements in primary and secondary outcome measures compared to the waiting list. -Conducting exposure in VR was more effective than in vivo exposure on specific outcome measures. -VR was significantly more practical for therapists than in vivo exposure. |

|

| 18–65 years old | The study discusses the development and testing of a VRET protocol for social anxiety disorder, focusing on modifying visual attention and gaze patterns during exposure therapy. Results show a reduction in fear of public speaking and general symptoms of social anxiety across both intervention groups. | -Lack of a non-socially anxious group at baseline for comparison -Absence of assessment of presence during treatment, potentially impacting efficacy -Clinicians not being blind to the treatment condition during follow-up assessments -Potential limitation of non-interactive public speaking challenges in the efficacy of social exposures |

-Attention can be modified within and during VRET. -Modifying visual gaze avoidance may be causally linked to reduced social anxiety. -The intervention had a significant overall effect on symptoms of social anxiety. |

|

| 39 mean years old | The study compares the efficacy of different treatments for agoraphobia, with combined treatments showing more significant improvements overall. Still, the superiority of virtual reality exposure in combination with therapy remains uncertain. | -Difficulty in determining phobic stimuli for each individual -Lack of determination of differential efficacy in groups not treated with psych drugs -Uncertainty regarding efficacy based on the acute or chronic nature of agoraphobia -Need for further data to confirm differential efficacy |