Submitted:

17 June 2024

Posted:

18 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

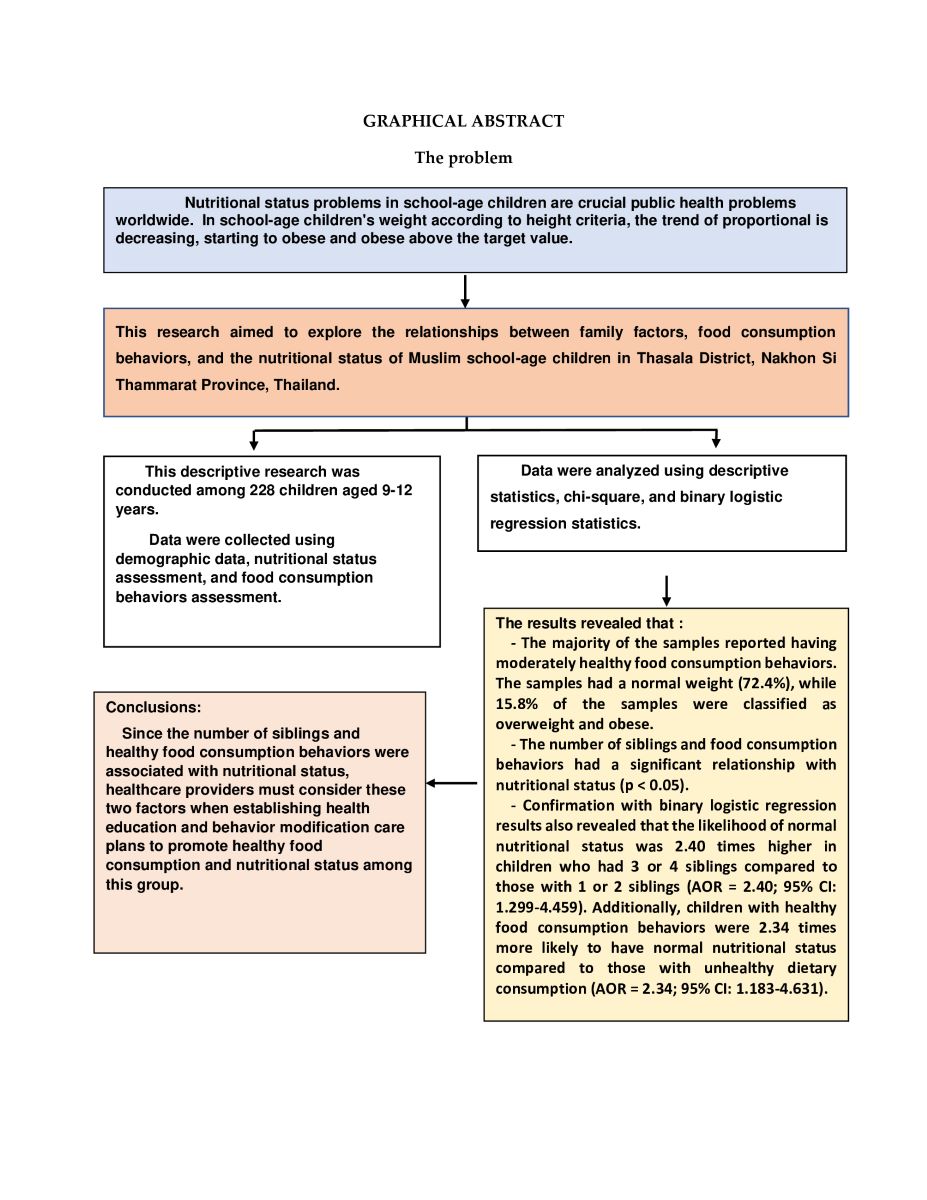

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Population and Sample Size

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Research Instruments

2.5. Ethical Statement

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Samples’ Demographics and Family Factors

3.2. Food Consumption Behavior among Muslim School-Age Students

3.3. Nutritional Status and Food Consumption Behaviors of Muslim School-Age Students

3.4. Relationships between Family Factors, Food Consumption Behaviors, and Nutritional Status

4. Discussion

4.1. Nutritional Status of Muslim School-Age Children

4.2. Relationship between Family Factors, Food Consumption Behaviors and Nutritional Status

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Statistical Office. Report of 17 selected provinces: Multiple indicator cluster survey 2019; National statistical office: Bangkok, Thailand, 2021; Available online: https://www.unice.forg/thailand/reports/mics-6-report-17-selected-provinces (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- World Health Organization. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates, Key findings of the 2021 edition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025257 (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Poh, B.K.; Wong, J.E.; Lee, S.T.; Chia, J.S.M.; Yeo, G.S.; Sharif, R.; Nik Shanita, S.; Jamil, N.A.; Chan, C.M.H.; Farah, N.M.; et al. Triple burden of malnutrition among Malaysian children aged 6 months to 12 years: Current findings from SEANUTS II Malaysia. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongcharoen, T.; Rojroongwasinkul, N.; Tuntipopipat, S.; Winichagoon, P.; Vongvimetee, N.; Phanyotha, T.; Sukboon, P.; Muangnoi, C.; Praengam, K.; Khouw, I. Southeast Asian Nutrition Surveys II (SEANUTS II) Thailand: Triple burden of malnutrition among Thai children aged 6 months to 12 years. Public Health Nutr. 2024, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Nutrition, Department of Health, Ministry of Public Health. Survey of health literacy and desired health behaviors in school-aged children in 2019; Department of Health, Ministry of Public Health: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2020; Available online: https://hp.anamai.moph.go.th/th/ewt-news-php-nid-1532/193576 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Christian Flemming, G.M.; Bussler, S.; Körner, A.; Kiess, W. Definition and early diagnosis of metabolic syndrome in children. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol Metab Definition and early diagnosis of metabolic syndrome in children. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol Metab. 2020, 33, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamad, D.; Raman, V. Metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. Transl. Pediatr. 2017, 6, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongchan, W. Prevention of metabolic syndrome of late school-age children: self-management. Journal of The Royal Thai Army Nurses. 2020, 21, 26–34. Available online: https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JRTAN/article/view/240943 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Parimanon, J.; Chaimay, B.; Woradet, S. Nutritional status and factors associated with nutritional status among children aged under 5 years: Literature review. The Southern College Network Journal of Nursing and Public Health 2018, 5, 329–342. Available online: https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/scnet/article/view/113003 (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Bureau of Nutrition, Department of Health, Ministry of Public Health. National Environmental Health Information System (NEHIS); Department of Health, Ministry of Public Health: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2020; Available online: https://dashboard.anamai.moph.go.th/nehis/default/index (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Nakhon Si Thammarat Provincial Statistical Office. Nakhon Si Thammarat Provincial Statistical Report 2020. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/116h9aGC0N36lMNQhoUh18Qh2mbphmrvb/view (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Bhusal, C.K.; Bhattarai, S.; Chhetri, P.; Myia, SD. Nutritional status and its associated factors among under five years Muslim children of Kapilvastu district, Nepal. PLoS One. 2023, 18, e0280375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murarkar, S.; Gothankar, J.; Doke, P.; Pore, P.; Lalwani, S.; Dhumale, G.; Quraishi, S.; Patil, R.; Waghachavare, V.; Dhobale, R.; et al. Prevalence and determinants of undernutrition among under-five children residing in urban slums and rural area, Maharashtra, India: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichaitum, S.; Juntarawijit, Y.; Hanrungcharotorn, U. Association between family factors and parenting style and nutritional status among students grade 4-6 in schools under the Office of the Basic Education Commission. Nursing Journal 2020, 47, 88–99. Available online: https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/cmunursing/article/view/242260 (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Lillahkul, N.; Supanakul, P. Way of life of Muslim people in Thailand’s Southern Provinces, and health-promoting lifestyle. The Southern College Network Journal of Nursing and Public Health. 2018, 5, pp. 302–312, Available online: thaijo.org/index.php/scnet/article/view/130912 (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Czepczor-Bernat, K.; Brytek-Matera, A. Children's and mothers' perspectives of problematic eating behaviors in young children and adolescents: An exploratory study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019, 16, 2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.R.; Chakrabarty, S.; Rakib, M.; Afrin, S.; Saltmarsh, S.; Winn, S. Factors associated with stunting and wasting in children under 2 years in Bangladesh. Heliyon. 2020, 6, e04849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Azuan, N.; Harun, N.; Ooi, Y.; Khor, B.H. Nutritional status and dietary fatty acid intake among children from low-income households in Sabah: A Cross-sectional study. Hm. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 36, 200260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waloh, W.; Perngmark, P.; Boonyasopun, U. Effects of self-efficacy promoting through family participation upon food consumption knowledge and nutritional status among upper-primary school underweight Muslim children, Pattani Province: A Pilot study. Princess of Naradhiwas University Journal 2023, 15, 98–120. Available online: https://li01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/pnujr/article/view/255258 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Bureau of Nutrition, Department of Health, Ministry of Public Health. Guide using the growth criteria for children ages 6-19; Department of Health, Ministry of Public Health: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2021; Available online: https://multimedia.anamai.moph.go.th/associates/guide-using-the-growth-criteria-for-children-ages6_19 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Bureau of Nutrition, Department of Health, Ministry of Public Health. Assessment of food consumption behavior of children aged 6-13 years; Department of Health, Ministry of Public Health: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2021; Available online: https://nutrition2.anamai.moph.go.th/th/book/206999 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Bloom, B.S.; Madaus, G.F.; Hastings, J.T. Handbook on formative and summative evaluation of student learning. McGraw-Hill: New York, 1971.

- Best, J.W.; Kahn, J.V. Research in education, 8th ed.; Butler University, Emeritus, University of Illinois, Chicago, 1998; 384.

- Jinakun, C.; Noonil, N.; Aekwarangkoon, S. The relationship between type of food consumption and nutrition status in primary school students in Nakhon Si Thammarat Province. J. Royal Thai Army Nurses. 2023, 24, 104–111. Available online: https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JRTAN/article/view/256318 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Devindran, D.; Ulaganathan, V.; Oeh, Z.Y.; Tan, L.X.; Kuralneethi, S.; Eng, Z.Y.E.; Lim, L.S.; Chieng, W.N.G.; Tay, J.L.; Lim, S.Y. Association between dietary diversity and weight status of aboriginal primary school children in Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 29, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Lahham, S.; Jaradat, N.; Altamimi, M.; Anabtawi, O.; Irshid, A.; AlQub, M.; Dwikat, M.; Nafaa, F.; Badran, L.; Mohareb, R.; et al. Prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity among Palestinian school-age children and the associated risk factors: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abduelkarem, A.R.; Sharif, S.I.; Bankessli, F.G.; Kamal, S.A.; Kulhasan, N.M.; Hamrouni, A.M. Obesity and its associated risk factors among school-Aged children in Sharjah, UAE. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0234244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaimongkol, L.; Daree, N.; Kabae, I. Breakfast skipping in school children: A case study of schools in the municipality and non-municipality area of Muang, Pattani Province. Journal of Nutrition Association of Thailand 2021, 56, 36–49. Available online: https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JNAT/article/view/247675 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Ernawati, F.; Efriwati Nurjanah, N.; Aji, G.K.; Hapsari Tjandrarini, D.; Widodo, Y.; Retiaty, F.; Prihatini, M.; Arifin, A.Y.; Sundari, D.; Rachmalina, R.; et al. micronutrients and nutrition status of school-aged children in Indonesia. J. Nutr. Metab. 2023, 4610038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Bhusal, CK.; Shrestha, B.; Bhattarai, KD. Nutritional status of children and its associated factors in selected earthquake-affected VDCs of Gorkha District, Nepal. International Journal of Pediatrics 2020 2020, 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastrad, P.; Neelopant, S.; Prasad, U.V.; Kirte, R.; Chandan, N.; Barvaliya, M.J.; Hatnoor, S.; Shashidhar, S.B.; Roy, S. Undernutrition among rural school-age children: A major public health challenge for an Aspirational District in Karnataka, India. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1209949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danso, F.; Appiah, MA. Prevalence and associated factors influencing stunting and wasting among children of ages 1 to 5 years in Nkwanta South Municipality, Ghana. Nutrition 2023, 110, 111996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhusal, U.; Sapkota, V. Socioeconomic and demographic correlates of child nutritional status in Nepal: An investigation of heterogeneous effects using quantile regression. Glob. Health 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamid, P.; Pongkaset, A.; Chainapong, K. Health literacy and influence of interpersonal relations towards food consumption behavior to prevent obesity among grade 6 students in municipality school, Yala Municipality. Academic Journal of Community Public Health. 2021, 7, pp. 35–46. Available online: https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/ajcph/article/view/244667 (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Khongtong, J. Factors affecting the nutritional purchasing behavior of students in Nakhon Si Thammarat Municipality. Wichcha Journal 2018, 37, 107–119. Available online: https://li01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/wichcha/article/view/129464 (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- National Statistical Office, Ministry of Digital Economy and Society. The 2017 food consumption behavior survey. Ministry of Digital Economy and Society: Bangkok, Thailand, 2018. Available online: https://www.nso.go.th/nsoweb/nso/survey_detail/aL (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Khamsuk, K.; Lanphukhiao, B.; Saowieng, J. Food consumption behaviors and the condition of nutrition in school children at Ban Nong Rangka School, Nakhon Ratchasima Province. In Proceedings of the 6th Academic Conference on Aging Society and Opportunities for Advancement in Higher Education, Nakhon Ratchasima College, Mueang, Nakhon Ratchasima, 30 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tong-on, P.; Charoendee, S.; Chaitiang, N. Factors related to nutritional status among preschool children in Phayao Province. Public Health & Health Laws J. 2019, 5, 139–150. Available online: https://so05.tcithaijo.org/index.php/journal_law/article/view/204768 (accessed on 15 March 2024).

| Demographics and family factors | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 93 | 40.8 |

| Female | 135 | 59.2 |

| Educational level | ||

| Grade 4 | 100 | 43.9 |

| Grade 5 | 65 | 28.5 |

| Grade 6 | 63 | 27.6 |

| Age | ||

| 9-10 years old | 104 | 45.6 |

| 11-12 years old | 124 | 54.4 |

| Primary caregiver | ||

| Father/mother | 183 | 80.3 |

| Grandparent/relatives | 45 | 19.7 |

| Number of siblings | ||

| 1-2 | 75 | 32.9 |

| 3-4 | 153 | 67.1 |

| Food consumption behaviors | M | SD | Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Having breakfast containing grains and animal protein or grains and milk | 2.34 | 0.50 | Healthy |

| 2. Having three main meals every day | 2.30 | 0.53 | Moderate |

| 3. Having two snacks every day | 2.24 | 0.56 | Moderate |

| 4. Eating 8 spoonfuls of rice or starch a day | 2.03 | 0.57 | Moderate |

| 5. Eating 4 servings of vegetables a day | 2.08 | 0.54 | Moderate |

| 6. Eating 3 servings of fruits a day | 2.20 | 0.53 | Moderate |

| 7. Eating 6 servings of meat a day | 2.19 | 0.58 | Moderate |

| 8. Drinking 3 packs/boxes of plain milk a day | 2.09 | 0.54 | Moderate |

| 9. Eating fish at least 3 days a week | 2.33 | 0.62 | Moderate |

| 10. Eating 3 or 4 eggs a week | 2.24 | 0.55 | Moderate |

| 11. Eating fatty meat, such as chicken or duck skin | 2.23 | 0.65 | Moderate |

| 12. Eating bakery products like cakes, pies, and doughnuts | 1.86 | 0.51 | Moderate |

| 13. Eating snacks | 1.71 | 0.59 | Moderate |

| 14. Adding more condiments to cooked foods | 1.86 | 0.59 | Moderate |

| 15. Adding more sugar to cooked foods | 1.99 | 0.61 | Moderate |

| 16. Eating iron-rich foods 1-2 days a week | 1.60 | 0.56 | Required modification |

| 17. Eating sweet snacks, ice cream, and chocolate | 1.46 | 0.51 | Required modification |

| 18. Drinking carbonated beverages, iced cocoa, and iced tea | 1.55 | 0.59 | Required modification |

| Overall | 2.01 | 0.56 | Moderate |

| Data | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Height-for-age (M = 139.2, SD = 10.1, Min-Max = 102-165 cm) | ||

| Severely stunted (< -2 SD) | 21 | 9.2 |

| Stunted (< -1.5 SD to -2 SD) | 20 | 8.8 |

| Normal height (-1.5 SD to +1.5 SD) | 156 | 68.4 |

| Tall (> +1.5 SD to +2 SD) | 9 | 3.9 |

| Tallness (> +2 SD) | 22 | 9.7 |

| Weight-for-age (M = 36.1, SD = 12.3, Min-Max = 20-90 kg) | ||

| Severely underweight (< -2 SD) | 10 | 4.4 |

| Underweight (< -1.5 SD to -2 SD) | 20 | 8.8 |

| Normal weight (-1.5 SD to +1.5 SD) | 151 | 66.2 |

| Mildly overweight (> +1.5 SD to +2 SD) | 13 | 5.7 |

| Excess weight (> +2 SD) | 34 | 14.9 |

| Weight-for-height | ||

| Severely wasted (< -2 SD) | 7 | 3.1 |

| Wasted (< -1.5 SD to -2 SD) | 13 | 5.7 |

| Normal weight (-1.5 SD to +1.5 SD) | 165 | 72.4 |

| Possible risk of overweight (> +1.5 SD to +2 SD) | 7 | 3.0 |

| Overweight (> +2 SD to +3 SD) | 26 | 11.4 |

| Obese (> +3 SD) Food consumption behaviors Healthy (35-54 score) Unhealthy (18-34 score) |

10 178 50 |

4.4 78.1 21.9 |

| Factors | Total | Abnormal nutritional status | Normal nutritional status | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary caregivers | |||||

| Father/mother | 183 (80.3) | 52 (28.4) | 131 (71.6) | 0.285 | 0.594 |

| Grandparent/relatives | 45 (19.7) | 11 (24.4) | 34 (75.6) | ||

| Number of siblings | |||||

| 1-2 | 75 (32.9) | 29 (38.7) | 46 (61.3) | 6.806 | 0.009** |

| 3-4 | 153 (67.1) | 34 (22.2) | 119 (77.8) | ||

| Food consumption behaviors | |||||

| Healthy | 178 (78.1) | 43 (24.2) | 135 (75.8) | 4.900 | 0.027* |

| Unhealthy | 50 (21.9) | 20 (40.0) | 30 (60.0) |

| Factors | Nutritional status | B | SE | Wald | df | EXP(B) | 95%CI | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal | Normal | lower | upper | |||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||||||||

| Primary caregivers | ||||||||||

| Grandparents/relatives Ref | 11 (24.4) | 34 (75.6) | 1 | |||||||

| Father/mother | 52 (28.4) | 131 (71.6) | 0.24 | 0.39 | 0.36 | 1 | 1.27 | 0.587 | 2.730 | 0.548 |

| Number of siblings | ||||||||||

| 1-2 Ref. | 29 (38.7) | 46 (61.3) | 1 | |||||||

| 3-4 | 34 (22.2) | 119 (77.8) | 0.87 | 0.32 | 7.79 | 1 | 2.40 | 1.299 | 4.459 | 0.005** |

| Food consumption behaviors | ||||||||||

| Unhealthy Ref | 20 (40.0) | 30 (60.0) | 1 | |||||||

| Healthy | 43 (24.2) | 135 (75.8) | 0.85 | 0.35 | 5.97 | 1 | 2.34 | 1.183 | 4.631 | 0.015** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).