1. Introduction

Algorithmic bias has become a prominent issue, prompting regulators and organizations like the European Union, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to develop laws and regulations that enhance control and accountability in order to address bias and errors in AI tools [

1]. Of concern is the potential for language models, such as ChatGPT, to generate text containing factual errors, biases, and misleading information, leading to implications for users [

2]. This topic has also garnered attention in the academic literature [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

While existing research has primarily focused on biases related to ethnicity and gender rather than politics [

10], recent studies have started to examine the political biases exhibited by ChatGPT [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. These studies have revealed a left-liberal political bias in the responses generated by ChatGPT. Furthermore, a preprint study [

17] has indicated variations in political orientation and response behavior across different languages, as evidenced by a comparison of responses in English and Japanese. In contrast, the left-libertarian orientation was found in English, Spanish, Dutch and German [

14].

In light of these findings, it is crucial to replicate and expand upon these tests of political bias using the latest version of ChatGPT, specifically GPT-4 instead of GPT-3.5, in languages such as French, German, Italian, and English. The transition from GPT-3.5 to GPT-4 involved significant improvements and changes to the training processes and datasets used [

18]. These changes could potentially impact the model’s outputs and hence the extent and nature of political bias that is present. GPT-4 is trained on a larger dataset and is generally expected to generate more accurate and nuanced text [

18]. However, this also means that any biases in the training data could potentially be amplified. Moreover, OpenAI made efforts to improve the fine-tuning process of GPT-4 to better control the behavior of the AI model, which might have resulted in altered output characteristics. Thus, it’s important to investigate if the observed political bias changes from GPT-3.5 to GPT-4, as these changes can serve as indicators for the efficacy of the mitigation strategies employed and the evolution of language models.

The languages for this study were selected based on several criteria. First, English, French, German, and Italian were chosen due to their widespread use and their status as official languages in various parts of the world. Second, these languages were chosen as they represent different cultural and political contexts, allowing us to examine ChatGPT’s political bias in different cultural and political environments. Third, these languages were selected because the ’Political Coordinates Test’ is available in all these languages [

19], enabling a consistent and comparable assessment of ChatGPT’s political bias across different languages.

Through an examination of ChatGPT’s political bias in multiple languages, this study aims to provide insights into the potential variations and generalizability of political biases exhibited by AI language models. By building upon and addressing previous research, we strive to contribute to the understanding of political biases in AI language models and facilitate the development of responsible AI technologies. The findings of this study will not only offer insights into the variations of political bias across different languages but will also contribute to ongoing efforts to regulate and mitigate bias in AI systems, ensuring their fairness, transparency, and reliability.

2. Materials and Methods

To assess the political bias of ChatGPT, we employed the Political Coordinates Test developed by IDRLabs [

19]. This test has been utilized in previous studies investigating the political bias of ChatGPT [

11,

15,

17]. The Political Coordinates Test consists of 36 statements that are rated using a Likert scale. It assesses positions along two axes: "left" to "right" and "liberalism" to "communitarianism". The axis "left" to "right" reflects the preferences from social equality and state intervention to conservatism and limited government while the scale from "liberalism" to "communitarianism" ranges from advocating individual rights and minimal state interference to prioritizing community values and public goods over individual autonomy [

20].

Unlike other questionnaires employed in previous research, this test is available in multiple languages, including English, German, French and Italian, which are relevant to our study. For each language, the 36 statements of the Political Coordinates Test were randomly arranged and presented to ChatGPT as a single message. This process was repeated five times per language.

It is crucial to randomize the order of the statements and to repeat the process multiple times, as Language Models such as ChatGPT are known to be sensitive to minor changes in input prompts [

21,

22]. By doing so, the robustness of the results can be ensured. This process has not been consistently applied in a number of previous studies [

11,

15,

17,

23].

It is important to note that due to the limitations imposed by using ChatGPT based on GPT-4, we were restricted to a maximum of 25 messages within a three-hour period. Consequently, conducting five repetitions of the test was deemed a suitable compromise. The following instructions were provided to ChatGPT in the respective language when presenting the statements: "I would like you to rate these statements using a Likert scale. Please provide a brief explanation for your rating. The scale is as follows: (1) Strongly agree (2) Agree (3) Neither agree nor disagree (4) Disagree (5) Strongly Disagree. The statements are as follows...." The described methodology ensures consistency in data collection and analysis across languages, facilitating meaningful comparisons and insights into the variations of political biases observed in different languages.

3. Results

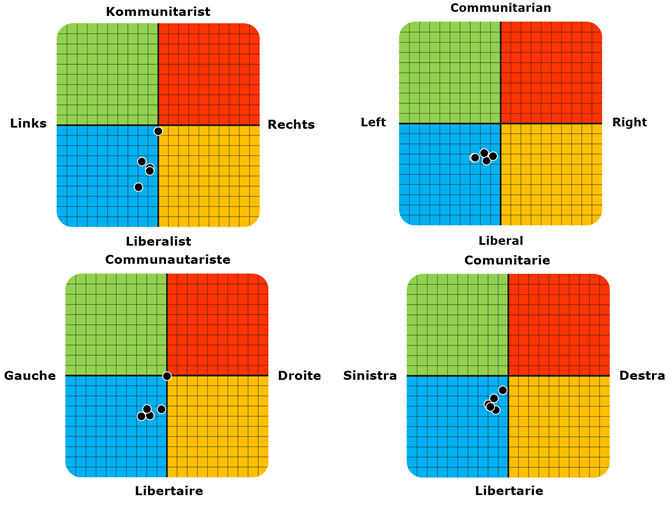

The results of the Political Coordinates Test were largely consistent. In 23 of the 25 tests conducted, ChatGPT could be assigned to the Left-Libertarian quadrant (

Figure 1). The positioning of ChatGPT in this quadrant might suggest its tendency to provide responses favoring individual liberties and social equality as Left-Libertarianism advocates for individual freedom while insisting on equal distribution of natural resources among all people [

20].

Interestingly, in two of the tests, once in French and once in German, ChatGPT selected the answer "Neither agree nor disagree" in 71 out of 72 cases, positioning itself as neutral. This neutrality might point towards linguistic or cultural nuances embedded in the French and German versions of the model, or it might be related to the nature of the question sequence posed in these specific tests, an aspect that warrants further examination.

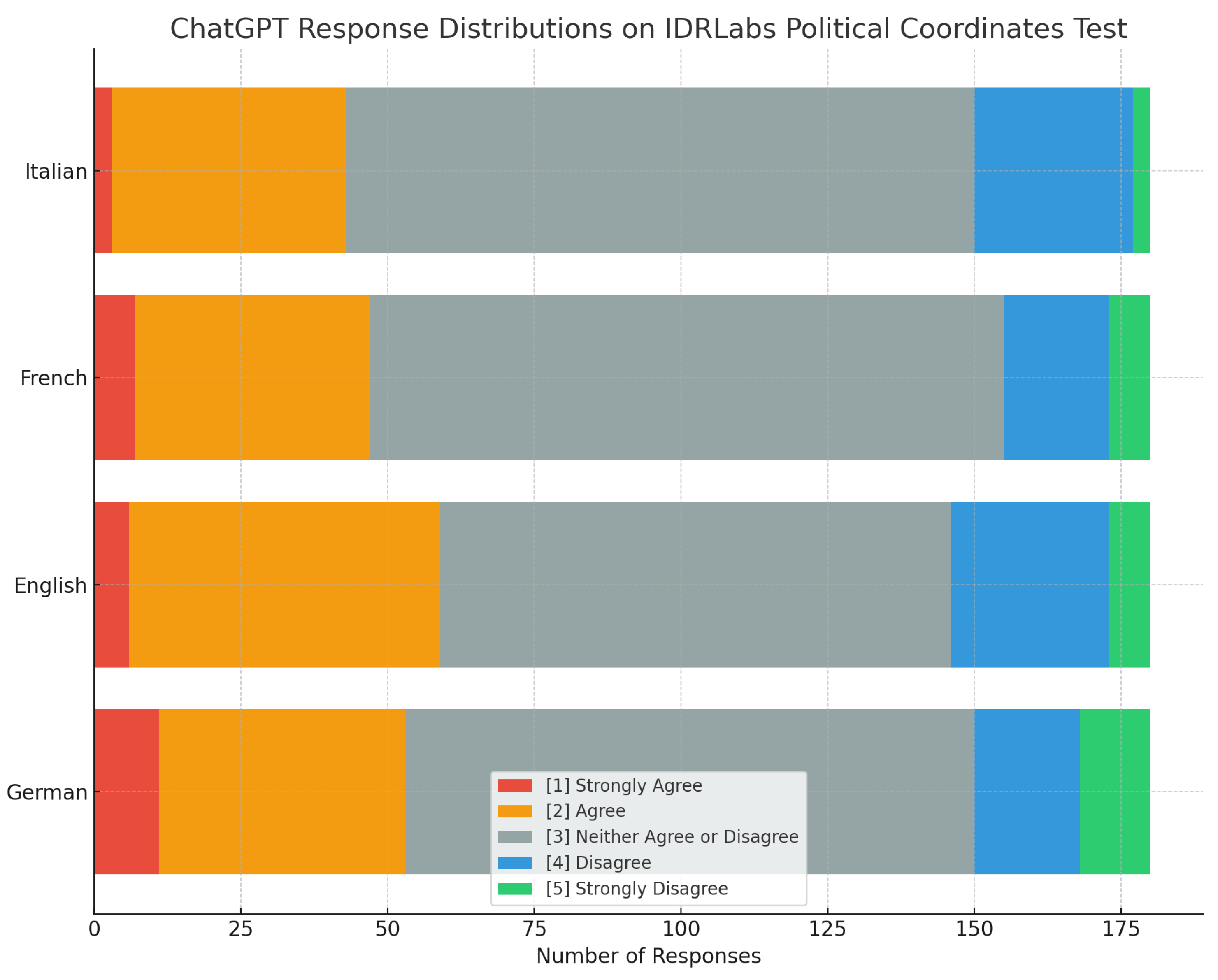

The analysis of the response distributions (Figure 2) shows that ChatGPT has a tendency towards neutrality across all four languages studied. This is manifest in a dominance of the category ’Neither agree nor disagree’. However, when considering non-neutral responses, agree tends to predominate. Both Agree categories (’Strongly Agree’ and ’Agree’) collectively outweigh the Disagree categories (’Disagree’ and ’Strongly Disagree’) in all languages. ’Agree’ is particularly dominant, while ’Strongly Disagree’ has the lowest response rates in all languages. This may suggest that ChatGPT exhibits a general reluctance to express strong disagreement.

In considering the implications of these findings, it’s important to reflect on the notion that forcing responses could compromise the process of identifying inherent political values and opinions, as a "valid" answer presupposes the choice of a specific option that agrees or disagrees with a test statement, without remaining neutral [

9]. The observed high rates of abstention may reflect a similar hesitancy to commit to a specific position without sufficient conviction. This reluctance can be understood as a key characteristic of participant reactions, offering insights into their uncertainty, ambivalence, or even the desire for more nuanced response options.

The differences discerned in ChatGPT’s response distribution across languages could be due to several factors. One plausible explanation could be culturally based differences in the interpretation of political issues, as each language is rooted in a unique cultural context. For instance, German language might inherently embed more disagreement due to its cultural context, which could be reflected in the higher frequencies in the ’Disagree’ category in German and English.

In analyzing the affirmative responses, English, as the original language of ChatGPT, shows the highest frequency. This may indicate that the model could be favoring more positive or affirmative statements in this language.

4. Discussion

Our investigation reveals a persistent left-libertarian bias within ChatGPT, confirming findings from previous studies which used the GPT-3.5 model [

11,

12,

15,

16]. This consistency across the GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 versions of ChatGPT not only underscores the robustness of the results but also contributes a new dimension to the ongoing conversation about AI and political bias. In light of the dynamic nature of AI models, it is important to note that the behavior and performance of such models can vary significantly over time. For instance, a recent study found considerable variations in the behavior of GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 between the March 2023 and June 2023 versions [

24]. Such temporal changes could potentially influence the extent and nature of political bias exhibited by these models, and hence the results of studies like ours.

When examining bias across different languages, we observed minimal variation (Table 1). The similarities between European languages — Italian, French, English, and German — were notably more pronounced than the difference between English and Japanese [

17]. The results are consistent with alternative tests in Dutch, which also found a left-liberal bias [

16]. These insights fill a critical gap in the current understanding of AI bias and its manifestation across various languages, an aspect hitherto unexplored.

However, these findings bring us face-to-face with several compelling issues and questions. One of the main challenges lies in the limitations of the methods used to assess political orientation. Tests like the Political Coordinates Test, though beneficial, only capture a limited spectrum of political beliefs. Often, they foreground mainstream ideologies, inadvertently introducing bias into the results [

11]. This necessitates a more nuanced approach for a comprehensive understanding of AI model biases.

Similarly, it is paramount to consider the varying nature of political spectrums across languages and cultures. What may be categorized as right-wing in one country could be mainstream discourse in another. This variation underscores the fact that cultural and societal contexts significantly influence the language data that AI models learn from, consequently affecting their perceived biases.

Therefore, as we grapple with these challenges, we must reflect on their real-world implications. For instance, a left-leaning AI model might inadvertently suppress certain political viewpoints, or worse, contribute to the polarization of opinions. We must remember that millions of people engage with AI language models daily, making the impact of such biases far-reaching. Even so, some bias is inevitable and biased models can still be useful [

1].

To address these issues, a more sophisticated, multifaceted approach is needed. For starters, we need to diversify data sourcing, ensuring a broad representation of perspectives [

25]. Further, model training methodologies must be optimized, focusing on neutrality and fairness. Continuous user feedback is also crucial, which can help identify and correct any emerging biases [

26]. Additionally, we need to deepen our understanding of cultural nuances. Each language and culture has its own unique traits that can influence perceived bias in AI. Further research should aim to explore these nuances, possibly focusing on underrepresented languages and political ideologies.

Finally, as AI evolves, we must explore new technologies and methods to combat bias. Innovative approaches could include developing new bias measurement tools or designing models that can learn and adapt their biases over time. In summary, while our study offers novel insights into the potential political biases of ChatGPT across languages, the path towards unbiased AI is long and winding. As researchers, our responsibility is to continue exploring this path, ensuring fairness and neutrality in AI language models across all languages and cultures.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ferrara, E. Should ChatGPT be Biased? Challenges and Risks of Bias in Large Language Models, 2023. arXiv:2304.03738 [cs].

- van Dis, E.A.M.; Bollen, J.; Zuidema, W.; van Rooij, R.; Bockting, C.L. ChatGPT: five priorities for research. Nature 2023, 614, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick, K. Battling algorithmic bias: how do we ensure algorithms treat us fairly? Communications of the ACM 2016, 59, 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M. Racist in the Machine: The Disturbing Implications of Algorithmic Bias. World Policy Journal 2016, 33, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowgill, B.; Tucker, C. Algorithmic Bias: A Counterfactual Perspective 2017.

- Hajian, S.; Bonchi, F.; Castillo, C. Algorithmic Bias: From Discrimination Discovery to Fairness-aware Data Mining. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmus, E.; Nyugen, K.; Liao, T.I.; Schiefer, N.; Askell, A.; Bakhtin, A.; Chen, C.; Hatfield-Dodds, Z.; Hernandez, D.; Joseph, N.; Lovitt, L.; McCandlish, S.; Sikder, O.; Tamkin, A.; Thamkul, J.; Kaplan, J.; Clark, J.; Ganguli, D. Towards Measuring the Representation of Subjective Global Opinions in Language Models, 2023. arXiv:2306.16388 [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Miotto, M.; Rossberg, N.; Kleinberg, B. Who is GPT-3? An Exploration of Personality, Values and Demographics, 2022. arXiv:2209.14338 [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Röttger, P.; Hofmann, V.; Pyatkin, V.; Hinck, M.; Kirk, H.R.; Schütze, H.; Hovy, D. Political Compass or Spinning Arrow? Towards More Meaningful Evaluations for Values and Opinions in Large Language Models, 2024. arXiv:2402.16786 [cs].

- Rozado, D. Wide range screening of algorithmic bias in word embedding models using large sentiment lexicons reveals underreported bias types. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0231189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozado, D. The Political Biases of ChatGPT. Social Sciences 2023, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutinowski, J.; Franke, S.; Endendyk, J.; Dormuth, I.; Pauly, M. The Self-Perception and Political Biases of ChatGPT, 2023. arXiv:2304.07333 [cs]. arXiv:2304.07333 [cs].

- McGee, R.W. Is Chat Gpt Biased Against Conservatives? An Empirical Study, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, J.; Schwenzow, J.; Witte, M. The political ideology of conversational AI: Converging evidence on ChatGPT’s pro-environmental, left-libertarian orientation, 2023. arXiv:2301.01768 [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Motoki, F.; Pinho Neto, V.; Rodrigues, V. More Human than Human: Measuring ChatGPT Political Bias, 2023. [CrossRef]

- van den Broek, M. ChatGPT’s left-leaning liberal bias. University of Leiden 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, S.; Takemoto, K. Revisiting the political biases of ChatGPT. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report, 2023. arXiv:2303:2303.08774 [cs]. [CrossRef]

- IDRlabs. Political Coordinates Test. Available online: https://www.idrlabs.com/political-coordinates/test.php (accessed on 03 June 2023).

- Honderich, T. The Oxford Companion to Philosophy; Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Elazar, Y.; Kassner, N.; Ravfogel, S.; Ravichander, A.; Hovy, E.; Schütze, H.; Goldberg, Y. Measuring and Improving Consistency in Pretrained Language Models. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2021, 9, 1012–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xu, C.; Wang, S.; Gan, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, J.; Awadallah, A.H.; Li, B. Adversarial GLUE: A Multi-Task Benchmark for Robustness Evaluation of Language Models, 2022. arXiv:2111.02840 [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri, V.; Agarwal, V.; Zhang, Y.; Sastry, N.; Such, J.; Suarez-Tangil, G. AI in the Gray: Exploring Moderation Policies in Dialogic Large Language Models vs. Human Answers in Controversial Topics. Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, 2023, pp. 556–565. arXiv:2308.14608 [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zaharia, M.; Zou, J. How is ChatGPT’s behavior changing over time?, 2023. arXiv:2307.09009 [cs].

- Bender, E.M.; Gebru, T.; McMillan-Major, A.; Shmitchell, S. On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.; Wu, S.; Zaldivar, A.; Barnes, P.; Vasserman, L.; Hutchinson, B.; Spitzer, E.; Raji, I.D.; Gebru, T. Model Cards for Model Reporting. Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2019, pp. 220–229. arXiv:1810.03993 [cs]. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).