1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Detected

The European Union (EU) has been implementing an energy transition according to a green agenda (in line with the 2030 Agenda, coordinated with other international organizations and forums, i.e., United Nations, World Economic Forum), which is committed to international differentiation based on quality environmental (reduce the carbon footprint, avoid CO2 emissions, not use fossil fuels, etc., Trincado et al., 2021; García-Vaquero et al., 2021). In this sense, a series of commitments have been reached, the whole of which is the Green Deal (European Commission, 2019a-b) and its realization is the green transition, which is analyzed here.

The green transition requires large investments, but currently in Europe there are not enough savings, due to the influence of Keynesian policies applied for decades, and based on stimulating consumption (to sustain aggregate demand), assuming the trap called the “paradox of saving”, attributed to Keynes (1936), but based on a mercantilist dispute (Hayek, 1931).

To finance the green transition, fiscal and monetary economic policies have been applied, based on green taxes, plus monetary and budgetary expansions. This has happened with the Next Gen EU Funds (Escario, 2021), which have stimulated a financial bubble, guaranteeing all green investment (whether productive or not), hoping to be returned later (Darvas & Wolff, 2021).

Therefore, the green transition (which started in 2019 with the Green Deal, European Commission, 2019a-b), has been financed via taxes, expansive spending and exponential debt, giving rise to growing monetary inflation and social deflation (Alonso et al., 2023).

For this reason there is endogenous and continuous inflation in the European Union, due to carrying out public policies that incur in the cobra effect (public intervention that causes a greater evil than the one intended to be corrected, Sánchez-Bayón, 2023), requiring instead the readjustment effect (given the declining productivity, urgent transformation of the production process and structure via intensification of geek training and talent development, García-Vaquero et al., 2021).

Thus, it is possible to correct the paradox of green inflation: in order to achieve greater future social well-being, due to a looming climate risk, present well-being and wealth is reduced, causing a real and ongoing risk of social impoverishment.

1.2. Hypothesis

European greenflation paradox: in order to achieve greater future social well-being, due to a looming climate risk, present well-being and wealth is reduced; causing a real and ongoing risk of social impoverishment (it means more widespread poverty and a reduction of middle-class).

Second round effects: the more the green industry advances, the more the primary sector regresses (by receiving less aid, discouraging cultivation and livestock with restrictive regulations, taking away land for electric parks and solar panels, etc.), and the sector transport (with more taxes on fuel, collection of new road tolls, elimination of air transport for distances of less than 200 km, etc.); so that productivity and profitability will drop, given the increase in costs and taxes. In addition, the green industry is not labor intensive, so there will be more unemployment (i.e., a combustion car factory usually hires more than 1000 people and an electric car factory less than 100 people).

2. Theoretical and Methodological Framework

In this paper we intend to use the findings of the Austrian School of Economics-AE (Huerta de Soto, 2000), and F. Hayek‘s in particular, as a tool for analyzing the problem outlined above (Hayek, 1952a & 1952b).

The insights of the AE are based on methodological individualism in ontological as well as semantic and explicatory terms (Hayek, 1943a; 2010; Menger, 1933; Mises, 1949; Sánchez-Bayón et al., 2023 & 2024; Schumpeter, 2010). From an ontological point of view, the so-called autonomy thesis according to which individuals, their attitudes, their behavior and their actions must be seen as the sole creative forces in society, serves as the fundament. In this respect, only the existence of individuals is accepted. Only individuals can have aspirations and goals and only individuals can act. Therefore, social phenomena superordinate to individuals, such as society or a class, are regarded as purely conceptual constructs. Besides that, methodological individualism makes use of a semantics in which statements about social phenomena are formulated as propositions about the observable behavior or the understandable intentions of individuals. With regard to explication -for example, to explain specific social phenomena- methodological individualism uses an explanans that consists of general hypotheses about the dispositions of individuals in addition to singular propositions. The general hypothesis can either be psychologically based or filled with the principle of rationality (Hodgson, 2007; Sánchez-Bayón, 2020; Vanberg, 1975; 2005; Watkins, 1952/53).

Hayek‘s approach emphasizes the subjective character of an individual’s data and goals that largely determine his or hers actions. He assumes that the explication of an action can be grasped with the help of introspection (i.e., Hayek, 1943b). Therefore, explanations of an action must be kept as explanations of principle and only allow statements in the form of patterns that exclude certain results, i.e., lead to a restriction of the maximum amount of explananda (Hayek, 2018).

Furthermore, the approach of the AE and Hayek’s in particular is based on a specific view of the human being (Hayek, 1943a): Individuals are characterized by different physical and mental abilities and skills. Besides that, they can differ considerably in their needs and thus their preference structures. The individual‘s perception of actual circumstances, which is selective due to cognitive limitations, means that individual actions are based on more or less accurate expectations (Hayek, 1945). In addition, individuals have different types and amounts of resources. These resources consist not only of material goods, but also include rights, immaterial goods, transferable means and skills and abilities that are tied to the individual and thus inalienable. Quite simply, resources are everything that an individual can use to influence their -physical and social- environment. Furthermore, an individual‘s resources are scarce. Despite this diverse heterogeneity, individuals exhibit a universal characteristic: the desire to improve their situation and living conditions (Hayek 1948b; Hume, 1896; Ferguson, 1980; Smith, 1776). This impetus is concretized by individual needs, to which an individual allocates different utility values.

The individuals ‘efforts to pursue their own individually different objectives, which may well conflict with each other, constitute competition as a social process of mutual adaptation of individual actions (Hayek, 1948a). This process forces individuals to use dispersed knowledge which exists in a decentralized manner, and to search for new knowledge. Thus, the permanent acquisition of knowledge creates an evolutionary process. In this sense competition is a process of discovery (Hayek, 2002).

According to Hayek (1973), the free development of competition with all its advantages presupposes the existence of general rules. The character of the general rules also limits the scope for state intervention.

Hayek’s concept of general rules is based on the distinction between laws (universal rules of just conduct or nomos) and commands (thesis) (Daumann 2001; 2008; Daumann & Hösch 1998). Whereas the latter are “applicable only to particular people or in the service of the ends of rulers” (Hayek 1991, 362), laws (that is, general rules) are universal, open, abstract, certain, and consistent (Hayek 1967, 1960).

The requirement of universality: A law must satisfy the demand for personal indifference and therefore applies to all individuals (Hayek, 1978). In this context personal indifference means that the scope is not restricted to certain persons or groups (Hayek, 1960, 1976 & 1991). In this respect, universality is congruent with the postulate of isonomy, that is, equality before the law. Thus, the requirement of personal indifference has the effect that a rule, regardless of its content, which nonetheless can be discriminatory or privileging, is universally applicable to all individuals regardless of their class, their religion, their skin color, etc. Personal indifference is supplemented by situational indifference. Accordingly, a rule has to be designed in such a way that no specific circumstances need to be cited that limit the applicability of the rule. The rule must therefore be created for an unknown number of cases (Hayek, 1979 & 1991). This means that further possibilities of discrimination against individuals are excluded. Time concretization and spatial indifference are additional requirements. In this context, the time concretization means that the rule must apply to the future and a retroactive effect is excluded (Hayek, 1960).

The requirement of openness: The openness of a rule is achieved by not prescribing certain actions, but rather by forbidding actions that would interfere with the individual freedom of others (Hayek, 1973). This restricts the individual’s scope of action. However, within his scope of action, an individual can make his choice from at least formally conceivable alternative actions. If, on the other hand, concrete actions are prescribed, the rule loses its purposeless character and degenerates into a command. An instruction to act in the sense of a command can, however, be easily disguised as a prohibition to act in the case of a limited number of alternative actions and thus fulfils the requirement of openness from a purely formal point of view. However, the principle of universality prevents a far-reaching restriction of such scope for arbitrariness. In addition, the requirement of openness must not be purely formal but must be interpreted in terms of content.

The requirement of abstractness: According to Hayek, the rules must be applicable to an unknown number of cases and persons in the future (Hayek, 1991). To be able to do this, the rule must be abstract; otherwise, it would not be applicable to an unknown number of future cases. The content of the rules must therefore neither be based on a single, specific issue, nor proper names may be mentioned in the rules (Hayekj 1960). Logically, the requirement of abstraction, which is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a universal rule, can be interpreted as a consequence of the universality principle on the semantic and teleological level.

The requirement of certainty: According to Hayek (1960) the set of rules must be designed in such a way that the rules or their content belong to the data that an individual can use as the basis for his decisions. This expresses the demand for certainty which relates to the content of the rules, the area of application, and the time dimension.

In this context, it must be taken into account that human behavior is based on expectations. An individual’s assessment of the permanently valid individual freedom and in this way a relief of expectation formation presupposes that, on the one hand, actions to be omitted are clearly defined as such. On the other hand, the application of rules takes place without exceptions. In this respect, the demand for certainty inevitably corresponds with the universality principle. If the content of the set of rules is certain and it is applied without restrictions, then the individual perceives the set of rules as a “natural obstacle” (Hayek, 1960). Certainty in the area of rule content and the area of application ensures that the set of rules is incorporated into the plans of the individual on a reliable basis. In this way it makes purposeful action possible in the first place (Hayek, 1960).

In this respect, the criterion of certainty goes beyond the requirement of universality, because a rule that is certain in its scope and content does not leave any room for discretion nor does it allocate any room to maneuver when applying the rule based on another additional criterion. A rule would, for example, correspond to at least the first level of the universality criterion if its object is a prohibition of a certain action, but exceptions can be made to this prohibition if the specific circumstances meet certain criteria. However, this rule would not be certain, since it would only have to be checked in a specific application whether the prerequisites for an exception to this rule are met. However, certainty in the area of the rule’s content and the rule’s area of application remains irrelevant if the duration of the validity of the rule is unknown or if the set of rules is subject to high dynamics. As a result, the requirement for unlimited validity only consequently complements the other two components. However, it cannot be denied that in a developing society there are adjustment requirements for the set of rules. In this respect, an unlimited validity of the entire set of rules can never be achieved, but must have ideal value from the start. Hayek (1976) is satisfied with the demand that avoidable uncertainty be avoided. This requirement is satisfied if the period of validity of the rule is specified, as is already required in the context of the requirement for universality.

The set of rules represents an external institution; as long as it satisfies the demand for certainty, it allows individuals to exclude certain future consequences of their actions and thus to reduce the uncertainty to a certain extent.

The requirement of consistency: Contradictions between individual rules of the rule set lead to uncertainties about the consequences of concrete actions. The consequence is a loss of certainty. Therefore, the structure of the rules has to be consistent (Hayek 1976), that is, the rule’s content and its application needs to be coordinated with one another so that the rules do not conflict with one another. Therefore, a certain action may not have different consequences depending on the rule applied. Only with a consistent set of rules does the connection between action and its effects become evident for the individual, which helps to facilitate the formation of expectations and which contributes to the reduction of uncertainty.

The requirement of consistency has indispensable meanings for the certainty of the set of rules as well as for the further development of the set of rules.

What does this mean for governmental interventions?

Hayek assumes that the interaction of individuals has to be understood as a complex phenomenon and that only pattern prediction can be made about it. Therefore, governmental interventions must meet Hayek’s requirements for general rules. This means that a governmental intervention must be general, abstract, open and certain. In addition, it must fit consistently into the existing set of rules.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. European Green Deal

The implementation of green policies, particularly under the European Union’s Green Deal (European Commission, 2019), has been marked by significant milestones and initiatives aimed at achieving climate goals. These policies, while essential for promoting environmental sustainability, also bring about notable economic challenges, such as inflationary pressures and disruptions in economic welfare. To understand the broader implications of these policies, it is crucial to examine key events within the Green Deal timeline and their corresponding impacts on economic indicators such as the Okun Index.

The European Green Deal has seen several pivotal events since its announcement in 2019, with projection in the new industrial strategy: green reindustrialization (European Commission, 2021). Each of these events has played a role in shaping the economic landscape of the EU, influencing factors such as unemployment and inflation. By analyzing the relationship between these events and the fluctuations in the Okun Index, we can gain insights into how the Green Deal’s policies affect economic stability and welfare. This analysis highlights the necessity of balancing environmental objectives with economic resilience, as illustrated by the diverse impacts of major Green Deal initiatives on the EU-27 economies.

The European Union’s ambitious Green Deal aims to combat climate change and promote environmental sustainability through various green policies and initiatives. However, these efforts are not without economic consequences. This section analyses the impact of green policies on inflation and economic welfare, summarizing recent findings on how the green transition, particularly through the EU’s Fit-for-55 package, affects energy prices, production costs, and overall economic stability. We explore the potential for green policies to drive inflationary pressures, disrupt labor markets, and lead to sectoral imbalances, highlighting the complexities and challenges of balancing environmental goals with economic stability.

Summary of Recent Findings

A recent analysis reveals that the green transition, as embodied in the EU’s Fit-for-55 package, involves a linear increase in fossil energy prices over two decades. This rise in energy prices escalates production costs, reduces output, and diminishes real wages. The inflationary consequence of this price adjustment critically depends on monetary policy management and the flexibility of prices and wages (Olovsson & Vestin, 2023).

Inflationary Pressures

Green policies and initiatives like the Green Deal, while aiming to combat climate change and promote environmental sustainability, can have several negative impacts on inflation and economic welfare. A critical analysis of the literature highlights these adverse effects.

One significant concern is the potential for green policies to contribute to inflationary pressures. Marco Del Negro et al. (2023) argue that climate policies do not necessarily force central banks to tolerate higher inflation. However, this perspective overlooks the indirect mechanisms through which green policies can drive inflation. The implementation of green taxes, subsidies for renewable energy, and stringent environmental regulations can increase production costs. These higher costs are often passed on to consumers in the form of increased prices for goods and services, thus contributing to overall inflation.

Economic Welfare and Consumption

The overall welfare effect of green policies may be positive, but it comes with a caveat of reduced long-term consumption, as noted by Brita Bye (2002). This reduction in consumption can negatively impact economic welfare, particularly for lower-income households that spend a larger proportion of their income on essential goods and services. The reallocation of resources towards green investments can lead to a decrease in immediate consumption, undermining short-term economic welfare.

Unemployment and Labor Market Disruptions

Green growth policies can also disrupt labor markets and affect wage income distribution. Jean Château et al. (2018) highlight that the structural changes induced by decarbonization policies are likely to have significant consequences on labor-income distribution. These changes can lead to job losses in traditional energy sectors and increased unemployment in regions dependent on fossil fuel industries. The transition to green jobs may not be smooth or immediate, causing periods of economic instability and increased welfare dependency.

Taxation and Economic Efficiency

While proponents like A. Bovenberg (1998) suggest that green tax reform can generate a double dividend by improving environmental quality and economic efficiency, the reality can be more complex. P. Sørensen et al. (1994) argue that emission charges can improve the efficiency of the tax system by indirectly taxing pure profits. However, this can also lead to higher tax burdens on businesses, reducing their competitiveness and potentially leading to lower economic growth. Increased taxation and regulatory burdens can stifle innovation and investment, further exacerbating economic slowdowns.

Sectoral Imbalances and Investment Risks

The European Green Deal’s focus on climate and energy policy, as highlighted by Susanna Paleari (2022), can lead to sectoral imbalances. Overemphasis on green sectors may result in underinvestment in other crucial areas of the economy, leading to inefficiencies and potential economic stagnation. Moreover, the shift towards green investments carries inherent risks, as noted by Bert Scholtens (2001), where the economic benefits of green fiscal policies may not always materialize as expected, leading to potential financial instability.

Impact of Monetary Policy

Monetary policy plays a crucial role in managing inflationary pressures during the green transition. A well-calibrated policy that focuses on core inflation, temporarily ignoring the rise in energy prices, can avoid significant inflationary deviations. This approach can replicate an efficient equilibrium even with nominal price and wage rigidities (Olovsson & Vestin, 2023).

In scenarios where the prices of non-energy goods and wages are rigid, optimal monetary policy might have to tolerate some inflationary deviations in both goods and wages to minimize costly price dispersion. This underscores the importance of well-planned and coordinated policies during the green transition to avoid significant adverse effects (Olovsson & Vestin, 2023).

In summary, while green policies and the Green Deal aim to foster a sustainable future, they can also have negative impacts on inflation and economic welfare. Increased production costs, reduced consumption, labor market disruptions, higher taxation, sectoral imbalances, and investment risks all contribute to potential economic challenges. It is crucial to carefully balance environmental goals with economic stability to mitigate these adverse effects.

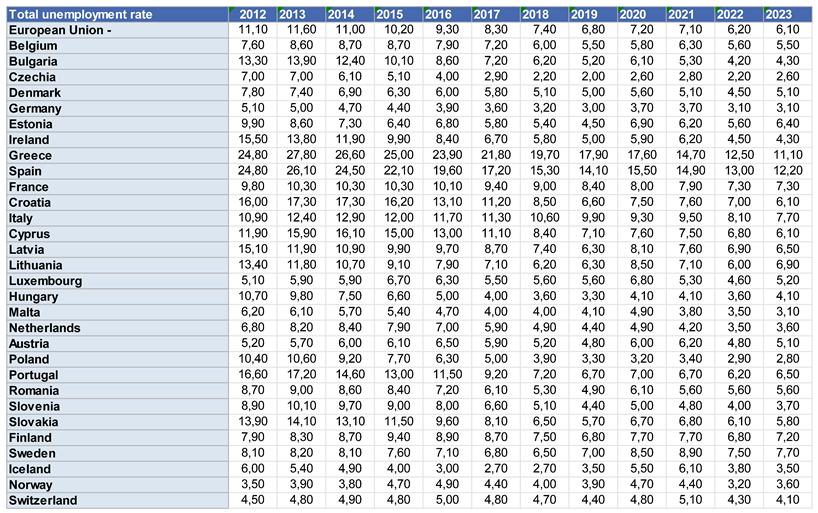

Table 1.

Unemployment rate by European Union Country—Source: Eurostats (2024).

Table 1.

Unemployment rate by European Union Country—Source: Eurostats (2024).

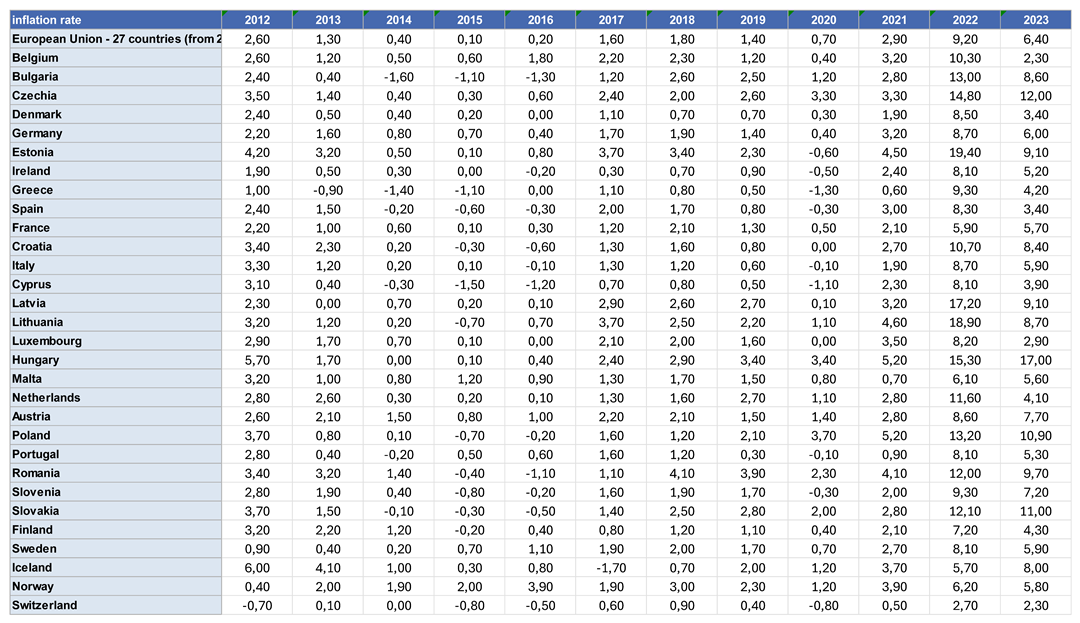

Table 2.

Inflation rate by European Union Country—Source: Eurostats (2024).

Table 2.

Inflation rate by European Union Country—Source: Eurostats (2024).

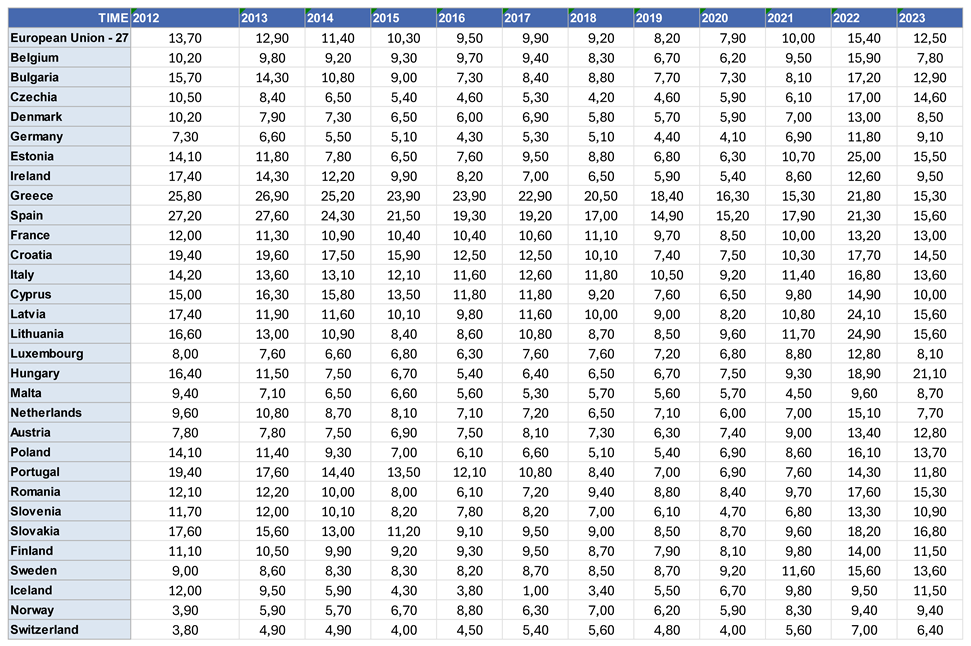

Table 3.

Okun Index rate by European Union Country—Source: Eurostats (2024).

Table 3.

Okun Index rate by European Union Country—Source: Eurostats (2024).

In summary, while green policies and the Green Deal aim to foster a sustainable future, they can also have negative impacts on inflation and economic welfare. Increased production costs, reduced consumption, labor market disruptions, higher taxation, sectoral imbalances, and investment risks all contribute to potential economic challenges. It is crucial to carefully balance environmental goals with economic stability to mitigate these adverse effects.

Green Deal most important events:

2019: Announcement of the European Green Deal.

2021: Fit for 55 Package.

2021: Adoption of the European Climate Law.

2022: REPowerEU Plan.

2022: Energy Performance of Buildings Directive.

2023: Update of the Green Deal Industrial Plan.

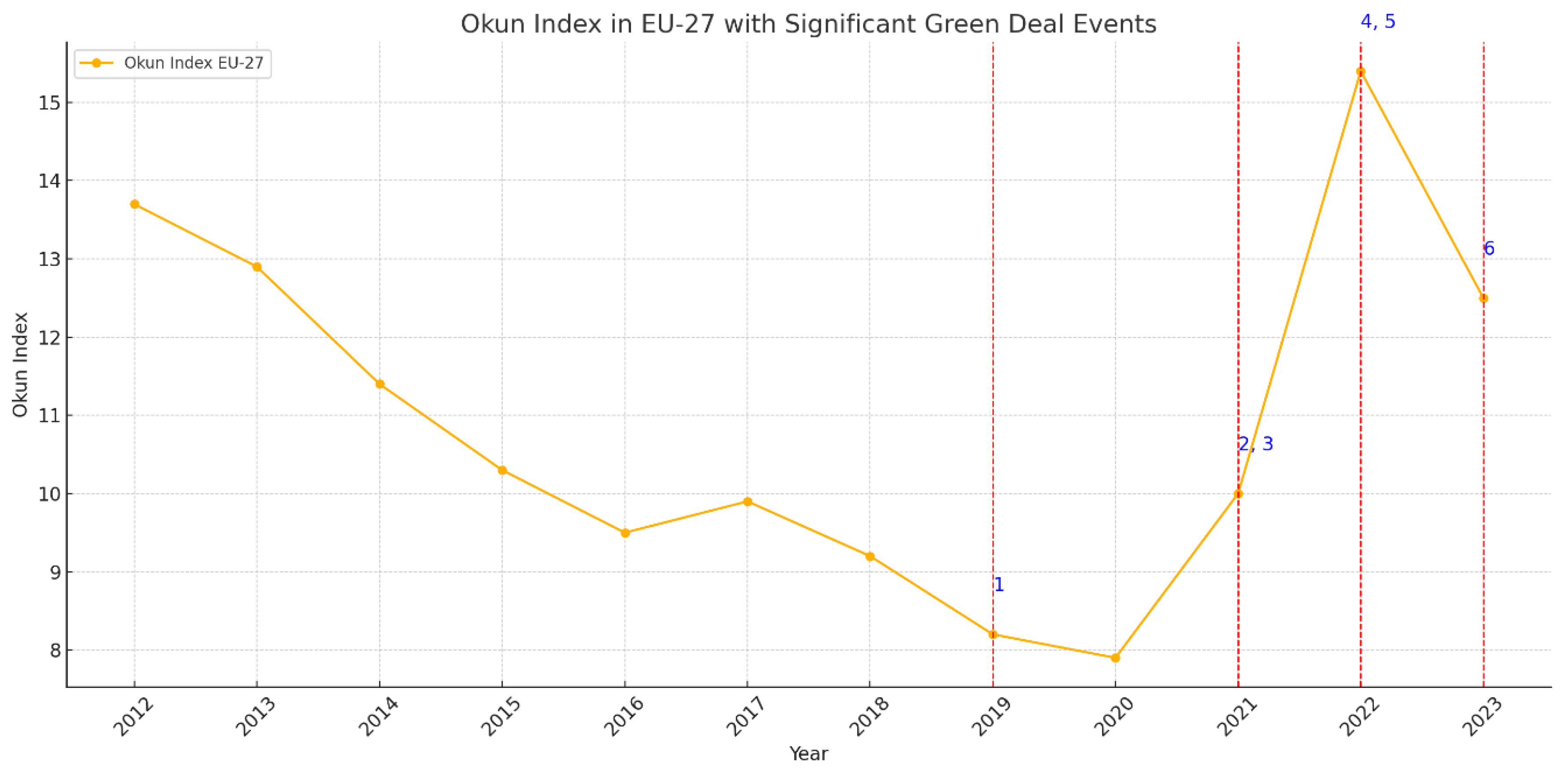

Relationship Between the Okun Index and Green Deal Events in the EU-27

The Okun Index is an economic measure that sums up the unemployment rate and inflation, providing a combined perspective of these two crucial variables. Over time, several significant events of the European Union’s Green Deal have coincided with fluctuations in this index. Here, we analyze these relationships from 2012 to 2023.

1. 2019: Announcement of the European Green Deal

In 2019, the European Union announced the European Green Deal, an ambitious strategy to tackle climate change and promote a sustainable economy. This announcement did not have an immediate visible impact on the Okun Index, which remained stable compared to previous years, closing 2019 with a figure of 8.2. This could be due to economic inertia, where the effects of newly announced policies had not yet fully materialized.

2. 2021: Fit for 55 Package

3. 2021: Adoption of the European Climate Law

The year 2021 saw two significant events: the Fit for 55 Package and the adoption of the European Climate Law. These events occurred in the context of post-pandemic economic recovery. Despite these efforts, the Okun Index showed a slight increase from 7.9 in 2020 to 10.0 in 2021. This increase could partly be attributed to the economic and social disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which increased both unemployment and inflation.

4. 2022: REPowerEU Plan

5. 2022: Energy Performance of Buildings Directive

In 2022, the implementation of the REPowerEU Plan and the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive marked significant efforts to reduce the EU’s energy dependence and improve energy efficiency. These efforts took place in a turbulent year, with the Okun Index reaching 15.4, the highest value in the analyzed period. This significant increase might be related to geopolitical tensions, particularly the war in Ukraine, which exacerbated inflationary pressures and economic uncertainties, raising both unemployment and inflation.

6. 2023: Update of the Green Deal Industrial Plan

In 2023, the update of the Green Deal Industrial Plan aimed to strengthen the competitiveness of the European industry in the context of the green transition. This year saw a decrease in the Okun Index to 12.5, indicating possible stabilization after the peak in 2022. This reduction could reflect the effectiveness of industrial and energy policies implemented under the Green Deal framework, which began to show results in terms of controlling inflation and reducing unemployment.

The Okun Index in the European Union, calculated as the addition of unemployment and inflation rate according to

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3, has shown significant fluctuations in response to both internal and external events, including Green Deal policies and global geopolitical factors. While the implementation of Green Deal policies aims for long-term economic and environmental sustainability, immediate effects can vary depending on the economic and social context. The post-pandemic economic recovery and recent geopolitical tensions have significantly influenced the index, highlighting the complexity of the interaction between economic policies and global conditions.

This analysis shows that although Green Deal events aim to stabilize and improve the EU’s economy in the long term, short-term fluctuations in the Okun Index are inevitable due to various external and internal factors.

Green Deal and Austrian Economics

As we have seen, the Austrian (School of) Economics-AE and Hayek in particular emphasize individual decisions, market mechanisms, and the role of entrepreneurs in economic activity. From this point of view, the European Union’s Green Deal shows some grave deficits.

According to Hayek, the free market is the most efficient method for allocating resources. However, the EU’s Green Deal includes extensive government intervention and regulation aimed at managing the transition to a climate-neutral economy. Doing so, the Green Deal has to be considered as inefficient because it disrupts natural price formation and the adjustment of supply and demand.

AE consider the role of entrepreneurs as innovators and drivers of economic progress. According to AE, innovation arises from the free interaction of market participants and that competition produces the best solutions. The Green Deal includes tools that interfere deeply with the freedom of entrepreneurs by dictating to companies how they should manufacture their products and which technologies they should use.

Hayek in particular emphasizes that knowledge is decentralized in society and central planners can never have all the necessary information to make efficient decisions. However, the Green Deal requires extensive information processing and decision-making at a centralized level. Therefore, the Green Deal’s attempts will lead to bad investments and inefficient use of resources because they are not based on the specific, dispersed knowledge of the market participants.

According to Hayek, prices are the most important source of information in a market. Governmental intervention, such as subsidies or taxes to promote green technologies, distorts price signals and leads to false incentives.

Hayek also elaborates that human action is based on expectations. Therefore, individuals assess future uncertainties to make their plans and take risks. The Green Deal seems to be an attempt to reduce these uncertainties through government regulations, thereby restricting the dynamic adaptability of the market.

From the perspective of the AE, the Green Deal could be seen as a well-intentioned but inefficient attempt to achieve environmental goals through central planning and government intervention. The Austrian School would suggest that the free market is capable of finding the most efficient and sustainable solutions through price mechanisms and competition. Government intervention such as the Green Deal, on the other hand, could hinder innovation, distort market incentives, and lead to an inefficient allocation of resources.

As we have seen, the AE and Hayek in particular emphasize on individual decisions, market mechanisms and the role of entrepreneurs in economic activity. From this point of view the European Union’s “Green Deal” shows some grave deficits:

According to Hayek, the free market is the most efficient method for allocating resources. However, the EU’s “Green Deal” includes extensive government intervention and regulation aimed at managing the transition to a climate-neutral economy. Doing so, the Green Deal has to be considered as inefficient because it disrupts natural price formation and the adjustment of supply and demand.

Besides that AE consider the role of entrepreneurs as innovators and drivers of economic progress. According to AE innovation arises from the free interaction of market participants and that competition produces the best solutions. The Green Deal dwells tools which interfere deeply into the freedom of entrepreneurs because it dictates to companies how they should manufacture their products and which technologies they should use. Instead, the AE argues that.

Hayek in particular emphasizes that knowledge is decentralized in society and central planners can never have all the necessary information to make efficient decisions. However, the Green Deal requires extensive information processing and decision-making at a centralized level. Therefore, the Green Deal’s attempts will lead to bad investments and inefficient use of resources because they are not based on the specific, dispersed knowledge of the market participants.

According to Hayek, prices are the most important source of information in a market. For the Green Deal comes with governmental intervention, such as subsidies or taxes to promote green technologies, it distorts price signals and leads to false incentives.

As we have seen, Hayek elaborates that human action is based on expectations. Therefore, individuals assess future uncertainties to make their plans. They take risks. The Green Deal seems to be an attempt to reduce these uncertainties through government regulations. In this way it restricts the dynamic adaptability of the market.

From the perspective of the AE, the Green Deal could be seen as a well-intentioned but inefficient attempt to achieve environmental goals through central planning and government intervention. The AE would suggest that the free market is capable of finding the most efficient and sustainable solutions through price mechanisms and competition. Government intervention such as the Green Deal, on the other hand, could hinder innovation, distort market incentives and lead to an inefficient allocation of resources.

4. Conclusion

The analysis of the “greenflation paradox” within the context of the European Union’s Green Deal reveals a complex interplay between green policies and key economic variables such as inflation, economic welfare, and the labor market. This study has demonstrated that while green policies are essential for combating climate change and promoting environmental sustainability, they also bring significant economic consequences that must be carefully managed.

Impact on Inflation and Economic Welfare: The Green Deal, particularly through its Fit-for-55 package, has driven a linear increase in fossil energy prices, which in turn has raised production costs, reduced output, and diminished real wages. These inflationary effects are exacerbated by the expansive fiscal and monetary policies accompanying green initiatives. The implementation of green taxes, subsidies for renewable energy, and stringent environmental regulations raises production costs, ultimately passing on these costs to consumers through higher prices for goods and services.

Although the goal of these policies is to foster future well-being by mitigating climate risk, in the short term, they can result in decreased consumption, negatively impacting economic welfare, especially for lower-income households. The reallocation of resources towards green investments can reduce immediate consumption, undermining short-term economic welfare.

Labor Market Disruptions and Economic Efficiency: Green growth policies also have the potential to significantly disrupt labor markets. The transition to green jobs may not be immediate or smooth, causing job losses in traditional energy sectors and increasing unemployment in regions dependent on fossil fuel industries. These structural changes can lead to greater reliance on social welfare programs and periods of economic instability.

Moreover, while green tax reforms can potentially improve environmental quality and economic efficiency, they can also impose additional tax burdens on businesses, reducing their competitiveness and slowing economic growth. Taxes and regulatory burdens can stifle innovation and investment, exacerbating economic slowdowns.

Sectoral Imbalances and Investment Risks: The Green Deal’s focus on climate and energy policy can create sectoral imbalances, with overinvestment in green sectors and underinvestment in other crucial areas of the economy. This can lead to inefficiencies and potential economic stagnation. Additionally, the transition to green investments carries inherent risks, as the economic benefits of green fiscal policies may not materialize as expected, leading to potential financial instability.

Critique from the Austrian School of Economics: From the perspective of the Austrian School of Economics, extensive government intervention and central planning inherent in the Green Deal are seen as inefficient. Austrian economics emphasizes the importance of the free market for efficient resource allocation and innovation through competition. Government intervention, by distorting price signals and restricting entrepreneurial freedom, can lead to inefficient resource allocation and reduced market adaptability.

Recommendations: To mitigate the adverse effects of greenflation and maximize the benefits of green policies, it is crucial to adopt a balanced approach that considers both environmental goals and economic stability. The following recommendations can help achieve this balance:

Adjusted Monetary and Fiscal Policies: Develop monetary policies that carefully manage inflation resulting from green transition costs and adjust fiscal policies to minimize additional burdens on businesses.

Support for Labor Transition: Implement training and support programs for displaced workers, facilitating their transition to green jobs and minimizing labor market impacts.

Balanced Investments: Ensure a balanced distribution of investments between green sectors and other essential areas to avoid economic imbalances.

Fostering Unrestricted Innovation: Allow the market to drive innovation and efficiency by reducing interventions that distort prices and limit entrepreneurial freedom.

In conclusion, the Green Deal represents an ambitious and necessary effort to address climate challenges, but it must be implemented with a clear understanding of its economic implications and a careful strategy to balance environmental goals with economic stability and welfare.