Submitted:

17 June 2024

Posted:

18 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Design and Population

2.2. Sample Size Determination and Sampling Procedure

2.3. Study Variables and Operational Definitions

2.4. Data Collection and Management

2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Respondents

3.2. Child Characteristics

3.3. Factors Related to Vaccine Refusal and Vaccination Service Satisfaction

3.4. Maternal Health Service

3.5. Vaccination Coverage

3.5.1. Proportion of Vaccination Based on Card Observation

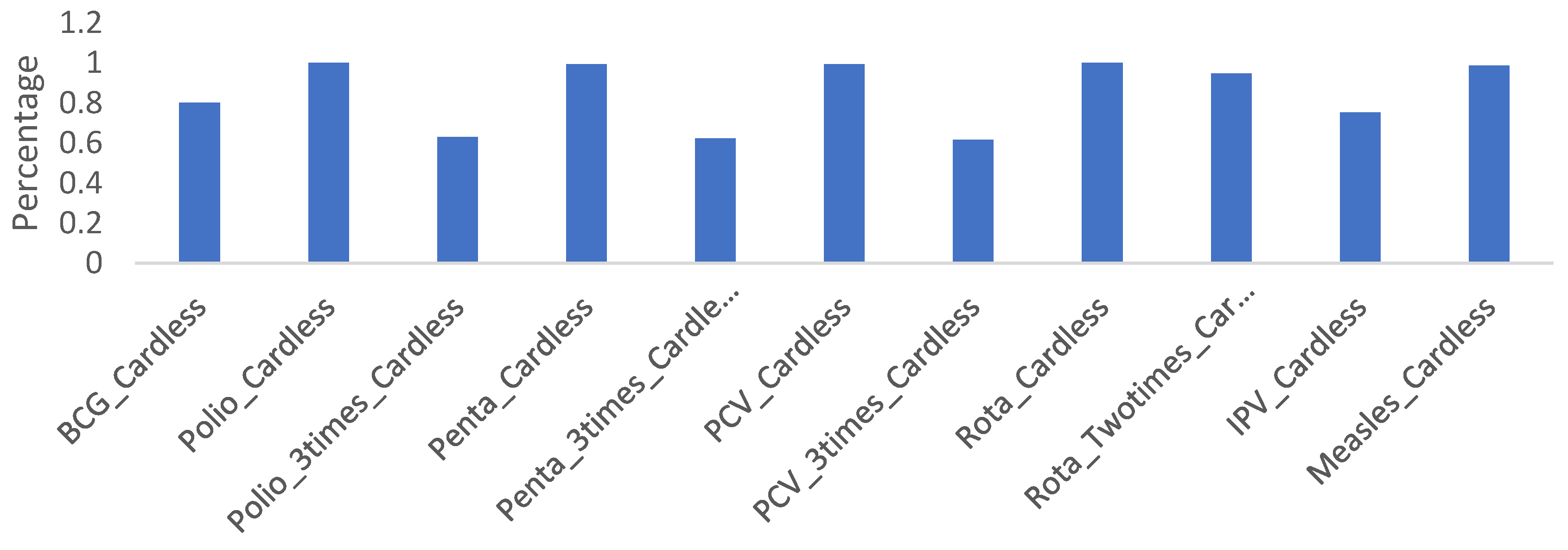

3.5.2. Proportion of Vaccination without Card Observation

3.5.3. Proportion of Full Immunization

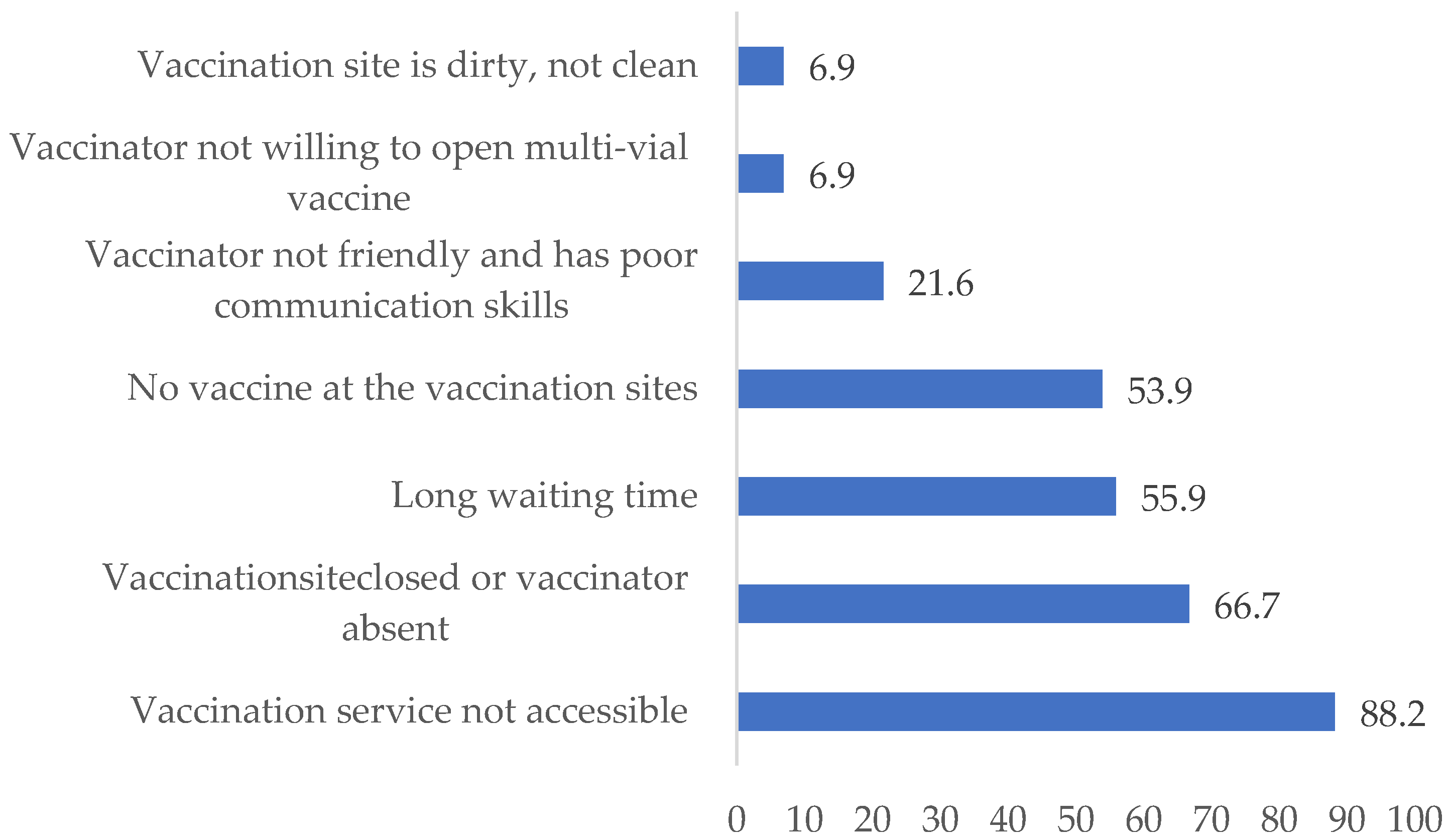

3.6. Barriers to Child Vaccination

The qualitative findings support that some of the key barriers to vaccination included the distance of the health facility, lack of health professional motivation, the desert weather conditions of Afar and community and partner engagement, which are some of the reasons for the low coverage of immunization.

"The health centre is far away from the majority of kebele residents. Thosecommunity members close to this health centre received frequent services from the institution, while those farther away from it did not often access the service. This scenario also applies toother health facilities in the region. Therefore, the long distance to the nearest health facility is the main barrier to EPI services.”

“The biggest problem fordesert or Berhama areassuch as the Afar region is the lack of health facilities, such as anearby health center, which makes vaccination services inaccessible andcreates problems in the supply of vaccines.”

“WhenCOVID-19 first began to spread in our nation, we had delays in implementing routine EPI delivery services. Later, whenthe COVID-19epidemic began to decline, we promptly resumed our normal EPI activities integrated withCOVID-19 prevention.”

“The major barriers tonot vaccinating children in our communities includea lack of commitment among health care workers, a shortage of EPI logistics and distribution,a lack of transportation access and high staff turnover.”

“There is a lack of incentive for health workers, HEWs, and women's developmental army.The provision ofincentives is the best way to motivate people and increase the performance of activities. In our cases, we triedthis approach, and weachieved betterresults. However, itwas not enough and was not supported by health higher officials. In addition, our woreda isa geographically vast, populated, and repeatedly conflict-affected area. The woreda had only one health centre, which made it very distant from three health posts. This madeit very difficult to conduct the expected follow-up and support on EPI services across different catchment areas.Therefore, additional health centres should be constructed, and conflict issues should alsoreceive attention and should beresolved permanently.”

“In this woreda vaccine service, delivery strategies are implemented only withthe initiative of NGOs, and this alone couldn’t solve our community’s problem at large. Therefore, itis essential to integrate woreda political leaders, community influential leaders and other concerned stakeholder leaders tobe involved in vaccine service delivery strategies.”

Amref Health Africa isan NGO partner thatis engaged in promoting the expansion of EPI vaccination coverage. Additionally, Amref and other stakeholders should support us build health posts in five difficult-to-reach kebeles in Woreda. Consequently, this will help us increase immunization coverage.”

“Amref, supported us on implementation of capacity building of voluntary communities Woreda level review meetings and the EPI Vaccination program.The WoredaHealth Office supported us in vaccinelogistics supply and transportation, but it is not enough if any partnersupported uswith a transportation vehicle with fuel; it would help us to enhance our vaccination coverage.”

“The community representatives should participate during the planning and implementation of immunization activities. For example, in deciding the outreach sites, targetidentification,and arrangement of the services.Therefore, their participation will help us toachievebetter vaccination coverage.”

3.7. Factors Associated with Full Immunization among Children

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO, G. Global Routine Vaccination Coverage 2011; Weekly Epidemiological record? . 2011.

- Pagè F, Maison D, Faulde M. 17Current control strategies for infectious diseases in low-income countries. In: Roche B, Broutin H, Simard F, editors. Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases: pathogen control and public health management in low-income countries: Oxford University Press; 2018. p. 0.

- Bhutta ZA, Sommerfeld J, Lassi ZS, Salam RA, Das JK. Global burden, distribution, and interventions for infectious diseases of poverty. Infect Dis Poverty. 2014;3:21. [CrossRef]

- Besnier E, Thomson K, Stonkute D, Mohammad T, Akhter N, Todd A, et al. Which public health interventions are effective in reducing morbidity, mortality and health inequalities from infectious diseases among children in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs): protocol for an umbrella review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e032981. [CrossRef]

- (WHO) WHO. Immunization, vaccines and biological.

- Federal Ministry of Health AFMoH, Addis Health, AddisAbaba ETHIOPIA NATIONAL EXPANDED PROGRAMME ON IMMUNIZATION 2015.

- Tesfaye TD, Temesgen WA, Kasa AS. Vaccination coverage and associated factors among children aged 12 - 23 months in Northwest Ethiopia. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(10):2348-54. [CrossRef]

- Nigatu T, Abraham L, Willems H, Tilaye M, Tiruneh F, Gebru F, et al. The status of immunization program and challenges in Ethiopia: A mixed method study. SAGE Open Med. 2024;12:20503121241237115. [CrossRef]

- Nour TY, Farah AM, Ali OM, Abate KH. Immunization coverage in Ethiopia among 12–23 month old children: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1134. [CrossRef]

- Zemariam AB, Abebe GK, Kassa MA, Alamaw AW, Molla RW, Abate BB, et al. Immunization coverage and its associated factors among children aged 12-23 months in Ethiopia: An umbrella review of systematic review and meta-analysis studies. PLoS One. 2024;19(3):e0299384. [CrossRef]

- Institute EPH. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019. Report. 2019.

- National Implementation Guideline for Expanded Program on Immunization (Revised edition), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. June 2021.

- Program: UHFI. Annual performance report, Ministry of Health Ethiopia 2014 EFY (2021/22).

- Ahmed M, Demissie M, Worku A, Abrha A, Berhane Y. Sociocultural factors favoring home delivery in Afar pastoral community, northeast Ethiopia: A Qualitative Study. Reproductive Health. 2019;16(1):171. [CrossRef]

- Yunusa U, Garba SN, Umar AB, Idris SH, Bello UL, Abdulrashid I, et al. Mobile phone reminders for enhancing uptake, completeness and timeliness of routine childhood immunization in low and middle income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2021;39(2):209-21. [CrossRef]

- Debie A, Amare G, Handebo S, Mekonnen ME, Tesema GA. Individual- and Community-Level Determinants for Complete Vaccination among Children Aged 12-23 Months in Ethiopia: A Multilevel Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:6907395. [CrossRef]

- Ketema DB, Assemie MA, Alamneh AA, Alene M, Chane KY, Alamneh YM, et al. Full vaccination coverage among children aged 12–23 months in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):777. [CrossRef]

- Fenta SM, Fenta HM. Individual and community-level determinants of childhood vaccination in Ethiopia. Archives of Public Health. 2021;79(1):53. [CrossRef]

- Venkataramanan R, Subramanian SV, Alajlani M, Arvanitis TN. Effect of mobile health interventions in increasing utilization of Maternal and Child Health care services in developing countries: A scoping review. Digit Health. 2022;8:20552076221143236. [CrossRef]

- Kassahun MB, Biks GA, Teferra AS. Level of immunization coverage and associated factors among children aged 12–23 months in Lay Armachiho District, North Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. BMC Research Notes. 2015;8(1):239. [CrossRef]

- Balogun SA, Yusuff HA, Yusuf KQ, Al-Shenqiti AM, Balogun MT, Tettey P. Maternal education and child immunization: the mediating roles of maternal literacy and socioeconomic status. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;26:217. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Woreda | ||

| Elidar | 154 | 36.8 |

| Dubti | 190 | 45.3 |

| Gereni | 75 | 17.9 |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 328 | 78.3 |

| Urban | 91 | 21.7 |

| Age | ||

| < 22 | 80 | 19.1 |

| 22-25 | 142 | 33.9 |

| 26-29 | 80 | 19.1 |

| ≥ 30 | 117 | 27.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 408 | 97.4 |

| Single/Divorced/Widowed | 11 | 2.6 |

| Maternal educational status | ||

| Unable to read and write | 345 | 82.3 |

| Read and write only | 43 | 10.3 |

| Primary school | 17 | 4.1 |

| Secondary and above | 14 | 3.4 |

| Fathers’ educational status | ||

| Unable to read and write | 296 | 70.6 |

| Read and write only | 58 | 13.8 |

| Primary school | 18 | 4.3 |

| Secondary school | 30 | 7.2 |

| College and above | 17 | 4.1 |

| Mother’s occupation | ||

| Housewife | 331 | 79.0 |

| Merchant | 40 | 9.5 |

| Farming/Pastoralist | 29 | 6.9 |

| Governmental employed | 17 | 4.1 |

| Other specify: | 2 | 0.5 |

| Religion status of respondent | ||

| Muslim | 398 | 95 |

| Orthodox | 21 | 5.0 |

| Mass media possession | ||

| Electrical/solar lump (light) | 162 | 38.7 |

| Radio | 139 | 33.2 |

| Television | 139 | 33.2 |

| Mobile phone | 307 | 73.3 |

| Household economic status | ||

| Able to meet basic needs | 343 | 81.9 |

| Unable to meet basic needs without charity | 52 | 12.4 |

| Refuse to answer | 14 | 3.3 |

| Able to meet basic needs and some nonessential goods | 9 | 2.1 |

| Able to purchase most nonessential goods | 1 | 0.2 |

| Total family size | ||

| < 4 | 155 | 37.0 |

| ≥ 4 | 264 | 63.0 |

| Distance to nearest health-post | ||

| ≤ 30 Minutes | 252 | 60.1 |

| > 30 Minutes | 167 | 39.9 |

| Distance to nearest health center | ||

| ≤ 30 Minutes | 137 | 32.7 |

| > 30 Minutes | 282 | 67.3 |

| Distance to the nearest vaccination center | ||

| ≤ 30 Minutes | 230 | 54.9 |

| > 30 Minutes | 189 | 45.1 |

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gravidity | ||

| ≤ 4 | 302 | 72.1 |

| > 4 | 117 | 37.9 |

| Parity | ||

| ≤ 4 | 332 | 79.2 |

| > 4 | 87 | 20.8 |

| Sex of index child | ||

| Male | 235 | 56.1 |

| Female | 184 | 53.9 |

| Age of indexed child in months | ||

| 12-13 | 127 | 30.3 |

| 13-16 | 100 | 23.9 |

| 17-20 | 89 | 21.2 |

| 21-23 | 103 | 24.6 |

| Order of indexed child | ||

| First | 48 | 11.5 |

| Second | 81 | 19.3 |

| Third | 115 | 27.4 |

| Fourth and later | 175 | 41.8 |

| Index childbirth condition | ||

| Single | 403 | 96.2 |

| Twins | 16 | 3.8 |

| Index child living with | ||

| Both parents | 399 | 95.2 |

| Mother only | 20 | 4.8 |

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Heard of vaccination | ||

| Yes | 313 | 74.7 |

| No | 106 | 25.3 |

| Advantages of vaccinating children (n=313) | ||

| To protect them from disease | 284 | 90.7 |

| To have healthy child | 224 | 71.6 |

| Have no benefits | 2 | 0.64 |

| Don’t know | 2 | 0.64 |

| Disadvantages of vaccine | ||

| Side or adverse effects | 210 | 67.1 |

| May make children sick | 178 | 56.9 |

| Takes time | 20 | 6.4 |

| Others (sterilize children, politics) | 12 | 3.8 |

| Don’t know/not sure | 50 | 16 |

| How likely vaccine prevent | ||

| Very likely | 191 | 61.0 |

| Somewhat likely | 45 | 14.4 |

| Not likely at all | 35 | 11.2 |

| Don’t know/not sure | 60 | 19.2 |

| Seriousness of vaccine preventable diseases | ||

| Very serious | 146 | 46.6 |

| Somewhat serious | 91 | 29.1 |

| Not serious at all | 33 | 10.5 |

| Don’t know/not sure | 55 | 17.6 |

| When to start | ||

| At birth | 78 | 24.9 |

| First few weeks | 34 | 10.9 |

| First few months | 121 | 38.7 |

| Later | 58 | 18.5 |

| Don’t know | 49 | 15.7 |

| Where to get child vaccine | ||

| Outreaches site | 139 | 44.4 |

| Health post | 110 | 35.1 |

| Health center | 183 | 58.5 |

| Public hospital | 51 | 16.3 |

| Received information on vaccination when the child was less than one year (n=313) | ||

| Yes | 239 | 76.4 |

| No | 74 | 23.6 |

| Source of information | ||

| Health professionals (doctors, nurses) | 193 | 80.8 |

| Health extension workers | 127 | 53.1 |

| Radio | 20 | 8.4 |

| Television | 48 | 20.1 |

| Other printed materials (poster, banner) | 6 | 2.5 |

| Husband/partner | 113 | 47.3 |

| Family/friend/neighbor | 68 | 28.5 |

| Religious/community leaders | 2 | 0.8 |

| Type of information heard | ||

| Importance of vaccination | 232 | 97.1 |

| About vaccination campaigns | 134 | 56.1 |

| Where to get routine vaccination | 43 | 18.0 |

| Timing for vaccination | 27 | 11.3 |

| Return to next doses of vaccination | 25 | 10.5 |

| Possible adverse events vaccination | 66 | 27.6 |

| Harms of vaccination | 20 | 8.4 |

| Don’t know/not sure | 4 | 1.7 |

| Informed about side effects | ||

| Yes | 239 | 76.4 |

| No | 74 | 23.6 |

| Informed what to do if adverse effects occurred | ||

| Yes | 236 | 98.7 |

| No | 3 | 1.3 |

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Ever refused child vaccine | ||

| Yes | 52 | 21.8 |

| No | 261 | 78.2 |

| Reasons for refusal | ||

| Too many injections at visit | 28 | 53.8 |

| Child was ill | 26 | 50.0 |

| Fear of injection pain | 21 | 40.4 |

| Fear of side effects | 11 | 21.2 |

| Fear of risk of disease transmission | 6 | 11.5 |

| Doubts on the benefit of the vaccine | 6 | 11.5 |

| Has already been vaccinated | 4 | 7.7 |

| Fear, doubts, suspicions about vaccine (n=313) | ||

| Yes | 27 | 8.6 |

| No | 278 | 88.8 |

| Not sure | 8 | 2.6 |

| Reasons for fear, doubts, suspicions about vaccine (n=27) | ||

| Vaccinations cause side effects | 15 | 55.6 |

| Vaccinations can make children sick | 8 | 29.6 |

| Vaccinations sterilize children | 2 | 7.4 |

| Others (Politics, religious) | 2 | 7.4 |

| Vaccine recommendation to other community members | ||

| Yes | 271 | 86.6 |

| No | 42 | 13.4 |

| Reasons not to recommend to others | ||

| Don’t believe vaccines are useful | 30 | 71.4 |

| Causes side effects/makes them sick | 29 | 69 |

| Injection can transmit diseases | 9 | 21.4 |

| Against social/religious norm | 1 | 2.4 |

| Satisfaction of vaccination service | ||

| Yes | 211 | 67.4 |

| No | 102 | 32.6 |

| ANC follow up | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 240 | 57.3 |

| No | 179 | 42.7 |

| Place of ANC booking | ||

| Health post | 66 | 27.5 |

| Health center | 152 | 63.3 |

| Public hospital | 67 | 27.9 |

| ANC frequency | ||

| ≤ 3 | 237 | 98.8 |

| > 3 | 3 | 1.2 |

| Information about child vaccination during ANC | ||

| Yes | 207 | 86.3 |

| No | 25 | 10.4 |

| Not sure/Don’t know | 8 | 3.3 |

| Place of birth | ||

| Home | 227 | 54.2 |

| Health facility | 192 | 45.8 |

| Birth assistance | ||

| Health professionals including HEWs | 192 | 45.8 |

| Traditional birth attendant | 214 | 51.1 |

| Family/friend/Neighbor | 11 | 2.6 |

| No one | 2 | 0.5 |

| Check up after birth | ||

| Yes | 103 | 24.6 |

| No | 316 | 75.4 |

| Who made the check-up | ||

| Health professionals | 93 | 90.3 |

| Health extension workers | 9 | 8.7 |

| Traditional birth attendant | 1 | 0.9 |

| Information on vaccination during check-up | ||

| Yes | 97 | 94.2 |

| No | 4 | 3.9 |

| Not sure/Don’t know | 2 | 1.9 |

| Vaccines | Proportion (total n=92) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| BCG | 97.8 (n=90) | 91.6%-99.5% |

| Polio-1 | 98.9 (n=91) | 92.5%-99.9% |

| Penta-1 | 96.7% (n=89) | 90.2%-98.9% |

| PCV-1 | 97.8% (n=90) | 91.6%-99.5% |

| IPV at 14 Week | 88.1% (n=81) | 79.5%-93.3% |

| Polio-2 | 90.2% (n=83) | 82.1%-94.9% |

| Penta-2 | 90.2% (n=83) | 82.1%-94.9% |

| PCV-2 | 89.1% (n=82) | 80.8%-94.1% |

| Polio-3 | 84.8% (n=78) | 80.8%-94.1% |

| Penta-3 | 83.7% (n=77) | 79.5%-93.3% |

| PCV-3 | 82.6% (n=76) | 80.8%-94.1% |

| Rota-1 | 97.8% (n=90) | 91.6%-99.5% |

| Rota-2 | 91.3% (n=84) | 83.4%-95.6% |

| Measles at 9 Months | 91.3% (n=84) | 83.4%-95.6% |

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Why children don’t vaccinate | ||

| Health workers did not come to the village | 247 | 58.9 |

| Domestic workload | 180 | 43.0 |

| Vaccination service not accessible | 155 | 37.0 |

| Vaccination site closed/vaccinator absent | 153 | 36.5 |

| Long waiting time | 138 | 32.9 |

| No vaccine at the vaccination sites | 106 | 25.3 |

| My husband discouraged me | 71 | 16.9 |

| Vaccination makes them sick | 33 | 7.9 |

| Vaccinator not friendly/poor relationship | 32 | 7.6 |

| Family/community discouraged me | 27 | 6.4 |

| Cultural or religious norms or beliefs | 14 | 3.3 |

| Vaccine approval status | ||

| Yes | 308 | 73.5 |

| No | 85 | 20.3 |

| Not sure/Don’t know | 26 | 6.2 |

| Approved positively by | ||

| Husband/Partner | 301 | 97.7 |

| Parents/parents in laws | 134 | 43.5 |

| Neighbors/peers | 105 | 34.1 |

| Other family members | 27 | 8.8 |

| Difficulty in remembering in vaccination schedule (n=247) | ||

| Not difficult at all | 51 | 20.7 |

| Somewhat difficult | 52 | 21.1 |

| Very difficult | 161 | 65.2 |

| Cultural taboos against vaccinating (n=419) | ||

| Yes | 66 | 15.8 |

| No | 328 | 78.3 |

| Don’t know/Not sure | 25 | 6.0 |

| Variables | Fully immunized | Crude odds ratio | Adjusted odds ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Health centre distance | ||||

| < 30 minutes | 55 | 82 | 3.11 (197-4.92) | 1.76 (0.40-1.41) |

| ≥ 30 minutes | 50 | 232 | 1 | 1 |

| Mobile | ||||

| Yes | 95 | 212 | 4.57 (2.29-9.14) | 2.99 (1.33-6.76)** |

| No | 10 | 102 | 1 | 1 |

| Maternal education | ||||

| Formal education | 23 | 2 | 10.73 (4.63-24.87) | 3.90 (1.53-9.98)** |

| No formal education | 82 | 306 | 1 | 1 |

| Child age | ||||

| 12-15 | 42 | 156 | 0.62 (0.37-1.04) | 0.66 (0.35-1.25) |

| 16-19 | 26 | 73 | 0.82 (0.45-1.48) | 0.61 (0.31-1.23) |

| 20-23 | 37 | 85 | 1 | |

| ANC visit | ||||

| Yes | 91 | 149 | 7.19 (3.93-13.18) | 2.39 (1.14-5.01)** |

| No | 14 | 165 | 1 | 1 |

| Place of birth | ||||

| Health facility | 87 | 105 | 9.62 (5.50-16.83) | 5.79 (2.77-12.12)** |

| Home | 18 | 209 | 1 | 1 |

| Birth order | ||||

| First | 15 | 33 | 1.64 (0.81-3.33) | 0.99 (0.42-2.36) |

| Second | 23 | 58 | 1.43 (0.78-2.61) | 1.32 (0.62-2.79) |

| Third | 29 | 86 | 1.22 (0.69-2.11) | 1.08 (0.57-2.07) |

| Fourth and later | 38 | 137 | 1 | |

| Information received during post-natal period | ||||

| Yes | 38 | 65 | 2.17 (1.34-3.52) | 0.74 (0.39-1.38) |

| No | 67 | 249 | 1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).