Submitted:

18 June 2024

Posted:

19 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Historical Development of Beef Farming in Brazil

2.1. The Transformation of Cerrado and Expansion to the North

2.2. The Launch of Improved Tropical Forage and New Husbandry Practices

2.3. Key Public Policies for Recent Developments of the Brazilian Agriculture

2.3.1. The Forest Code

2.3.2. The ABC Program and the ABC+ Plan

2.4. Sustainable Intensification: The Path to Brazilian Low Carbon Beef

3. Discussion: Social Inclusion and other Challenges for the Brazilian Beef Farming

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. (2023). FAOLEX Database - Brazil. Available at:<https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC222677/#:~:text=In%20particular%2C%20the%20objectives%20of,set%20out%20in%20the%20international>. Access: 18 Jan. 2024.

- ABIEC. (2023) Beef Report 2023. São Paulo, SP: ABIEC. https://www.abiec.com.br/publicacoes/beef-report-2023.

- Basso, M.F., Neves, M.F. and Grossi-de-Sa, M. (2024) Agriculture evolution, sustainability and trends, focusing on Brazilian agribusiness: a review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1296337. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, T., Luna, I., Miranda, S.H.G., 2020. Network analysis of cattle movement in Mato Grosso do Sul (Brazil) and implications of foot-and-mouth disease. Front. Vet. Sci. 7 (219), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Malafaia, G.C.; Mores, G. de V.; Casagranda, Y.G.; Barcellos, J.O.J.; Costa, F.P. The Brazilian beef cattle supply chain in the next decades. Livestock Science, v. 253, p. 104704, 2021.

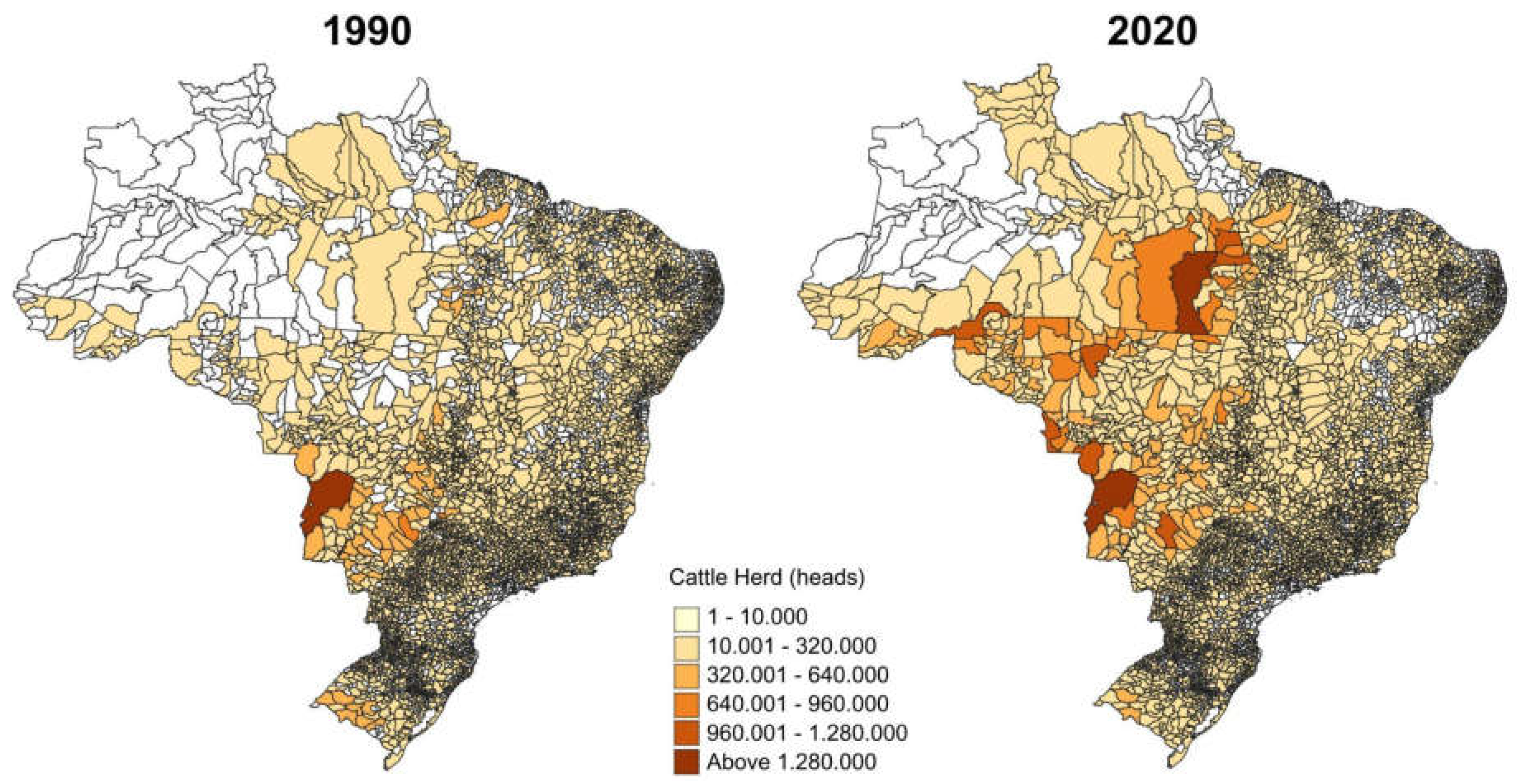

- McManus, C., Barcellos, J.O.J., Formenton, B.K., Hermuche, P.M., Carvalho, O.A.d, Jr, Guimarães, R. et al. (2016). Dynamics of Cattle Production in Brazil. PLoS ONE 11(1): e0147138. [CrossRef]

- Chaddad, F. The economics and organization of Brazilian agriculture: recent evolution and productivity gains. Elsevier, 2015. San Diego [USA]. eBook ISBN: 9780128018071.

- Mores, G.d.V., Dewes, H., Talamini, E., Vieira-Filho, J.E.R., Casagranda, Y.G., Malafaia, G.C., Costa, C., Spanhol-Finocchio C.P., Zhang, D. A Longitudinal Study of Brazilian Food Production Dynamics. Agriculture. 2022; 12(11):1811. [CrossRef]

- Faminow, M.D. (1996) Spatial economics of local demand for cattle products in Amazon development. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 62, 1-11.

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2022).www.ibge.gov.br.

- Carvalho, C. A. de. Ocupação e uso de terras no Brasil a partir do Cadastro Ambiental Rural - CAR. Revista da APEAESP, v. 3, 2019. 11 p. Available at: https://ainfo.cnptia.embrapa.br/digital/bitstream/item/169283/1/4882.pdf Access: 10 Feb. 2024.

- ABIEC. (2019) Beef Report 2019. São Paulo, SP: ABIEC. Available at: https://www.abiec.com.br/publicacoes/beef-report-2019 Access: 25 Mar. 2024.

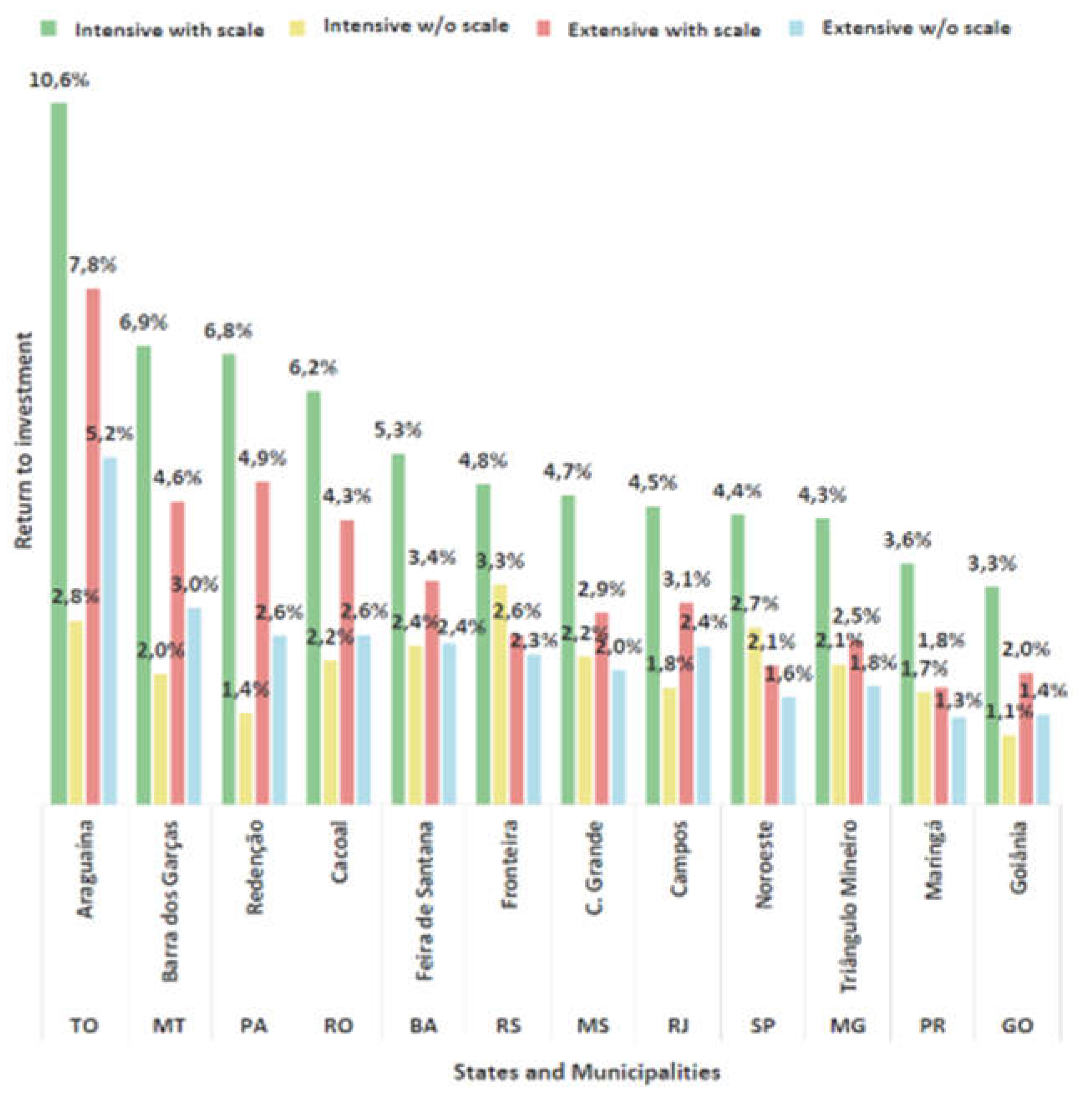

- Deblitz, C. 2023. Beef and Sheep Season: a summary of main findings. Agri benchmark.2023.Availableat:http:// http://catalog.agribenchmark.org/blaetter katalog/BeefSheepReport_2023/. Access: 14 Feb 2024.

- Valle, C.B.do; Jank, L.; Resende, R.M.S. O melhoramento de forrageiras tropicais no Brasil. Revista Ceres, v.56, p.460-472, 2009.

- A.A. Miszura, M.V.C. Ferraz, R.C. Cardoso, D.M. Polizela, G.B. Oliveira, J.P.R. Barroso, L.G.M. Gobato, G.P. Nogueira, J.S. Biava , E.M. Ferreira, A.V. Pires. Implications of growth rates and compensatory growth on puberty attainment in Nellore heifers Domestic Animal Endocrinology 74 (2021) 106526. [CrossRef]

- PS Baruselli, EL Reis, MO Marques, LF Nasser, GA Bo. The use of hormonal treatments to improve reproductive performance of anestrous beef cattle in tropical climates. Animal Reproduction Science, 82-83 (2004), pp. 479-486.

- Lima, P. R. M., Peripolli, V., Josahkian, L. A., McManus, C. M. (2023). Geographical distribution of zebu breeds and their relationship with environmental variables and the human development index. Scientia Agricola, 80, e20220008. [CrossRef]

- Euclides Filho, K. Evolução do melhoramento genético de bovinos de corte no Brasil. Revista Ceres, v. 56, n.5, p.620-626, 2009.

- R.S. de Lima, T. Martins, K.M. Lemes, M. Binelli, E.H. Madureira. Effect of a puberty induction protocol based on injectable long acting progesterone on pregnancy success of beef heifers serviced by TAI. Theriogenology 154 (2020) 128-134. [CrossRef]

- Terakado, A.P.N.; Pereira, M.C.; Yokoo, M.J.; Albuquerque, L.G. Evaluation of productivity of sexually precocious Nelore heifers. Animal, 9:938-943, 2015.

- Associação Brasileira de Inseminação Artificial. (ASBIA). Index ASBIA Mercado, 2022. https://asbia.org.br/wp-content/uploads/Index/Index_ASBIA_2022.pdf.

- Nogueira, É.; Silva, M.R. ; Borges Silva, J. C. ; Abreu, Pinto, U.G.; Anache, N.A.; Silva, K. C. ; Cardoso, C. J. T. ; Sutovsky, P.; Rodrigues, W.b . Timed artificial insemination plus heat I: effect of estrus expression scores on pregnancy of cows subjected to progesterone?estradiol-based protocols. Animal, v. 13(10)., p. 1-8, 2019.

- Baruselli, P.S., Catussi, B.L.C., Abreu, L.Â. de, Elliff, F.M., Silva, L.G. da, Batista. E.O.S. Challenges to increase the AI and ET markets in Brazil Anim. Reprod., v.16, n.3, p.364-375, Jul./Sept. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, A. O.; Nicacio, A. C. ; Menezes, G. R. O. ; Gomes, R. C. ; Silva, L.O.C. ; Rocha-Frigoni, Souza, N.A.de; Mingoti, G.Z.; Leão, B.C.daS.; Costa e Silva, E. V.; Nogueira, É. Comparison between in vitro embryo production using Y-sorted sperm and timed artificial insemination with non-sorted sperm to produce crossbred calves. ANIMAL REPRODUCTION SCIENCE, v. 208, p. 106101, 2019.

- Pontes, J. H. F., Silva, K. C. F., Basso, A. C., Rigo, A. G., Ferreira, C. R., Santos, G. M. G., Sanches, B. V., Porcionato, J. P. F., Vieira, P. H. S., Faifer, F. S., Sterza, F. A. M., Schenk, J. L., Seneda, M. M. (2010). Large-scale in vitro embryo production and pregnancy rates from Bos taurus, Bos indicus, and indicus-taurus dairy cows using sexed sperm. Theriogenology, 74(8), 1349-1355. [CrossRef]

- Sales, J. N. S., Iguma, L. T., Batista, R. I. T. P., Quintão, C. C. R., Gama, M. A. S., Freitas, C., Pereira, M. M., Camargo, L. S. A., Viana, J. H. M., Souza, J. C., Baruselli, P. S. (2015). Effects of a high-energy diet on oocyte quality and in vitro embryo production in Bos indicus and Bos taurus cows. Journal of Dairy Science, 98(5), 3086-3099. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J. C. De; Darsie, G. Deficiencias minerais em bovinos de Roraima, Brasil I. zinco e cobalto. Pesquisa Agropecuaria Brasileira, Brasilia, v.20, n.11, p.1309-1316, nov. 1985.

- Sousa, J. C. De; Nicodemo, M. L. F.; Darsie, G. Deficiências Minerais em Bovinos de Roraima, Brasil. V. Cobre e Molibdênio. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira, Brasília, v.24, n.12, p.1547-1554, dez. 1989.

- Tokarnia, C. H.; Döbereiner, J; Peixoto, P. V. Deficiências minerais em animais de fazenda, principalmente bovinos em regime de campo. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira, Rio de Janeiro, v. 20, n. 3, p. 127-138, 2000.

- Araújo, I. M. M. De; Difante, G Dos S.; Euclides, V. P. B.; Montagner, D. B.; Gomes, R. Da C. Animal Performance with and without Supplements in Mombaça Guinea Grass Pastures during Dry Season. Journal of Agricultural Science, v. 9, n. 7, p. 145-154, July 2017.

- Silvestre, A. M., Millen, D. D. 2021. The 2019 Brazilian survey on nutritional practices provided by feedlot cattle consulting nutritionists. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia 50:e20200189.

- Barbosa, F. R. G. M.; Duarte, V. N.; Staduto, J. A. R. The expansion of the agricultural frontier and the dynamics of land use in the Brazilian Center-West region (1996-2017). In: SOBER, 56, 2021, Brasilia, DF. Anais… Brasília: SOBER, p.

- Stabile et al. 2023. Land Sparing and Sustainable Intensification within the Livestock Sector. In: Søndergaard, N. et al. (eds.), Sustainability Challenges of Brazilian Agriculture, Environment & Policy 64. [CrossRef]

- Chiavari, J., Lopes, C.L., Machado, L. A. (2023). The Brazilian Forest Code: The Challenges of Legal Implementation. In: Søndergaard, N., de Sá, C.D., Barros-Platiau, A.F. (eds) Sustainability Challenges of Brazilian Agriculture. Environment & Policy, vol 64. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. (2012) Plano setorial de mitigação e de adaptação às mudanças climáticas para a consolidação de uma economia de baixa emissão de carbono na agricultura: Plano ABC (Agricultura de Baixa Emissão de Carbono). Brasilia, DF: MAPA, 173 p.https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/sustentabilidade/agricultura-de-baixa-emissao-de-carbono/publicacoes/download.pdf.

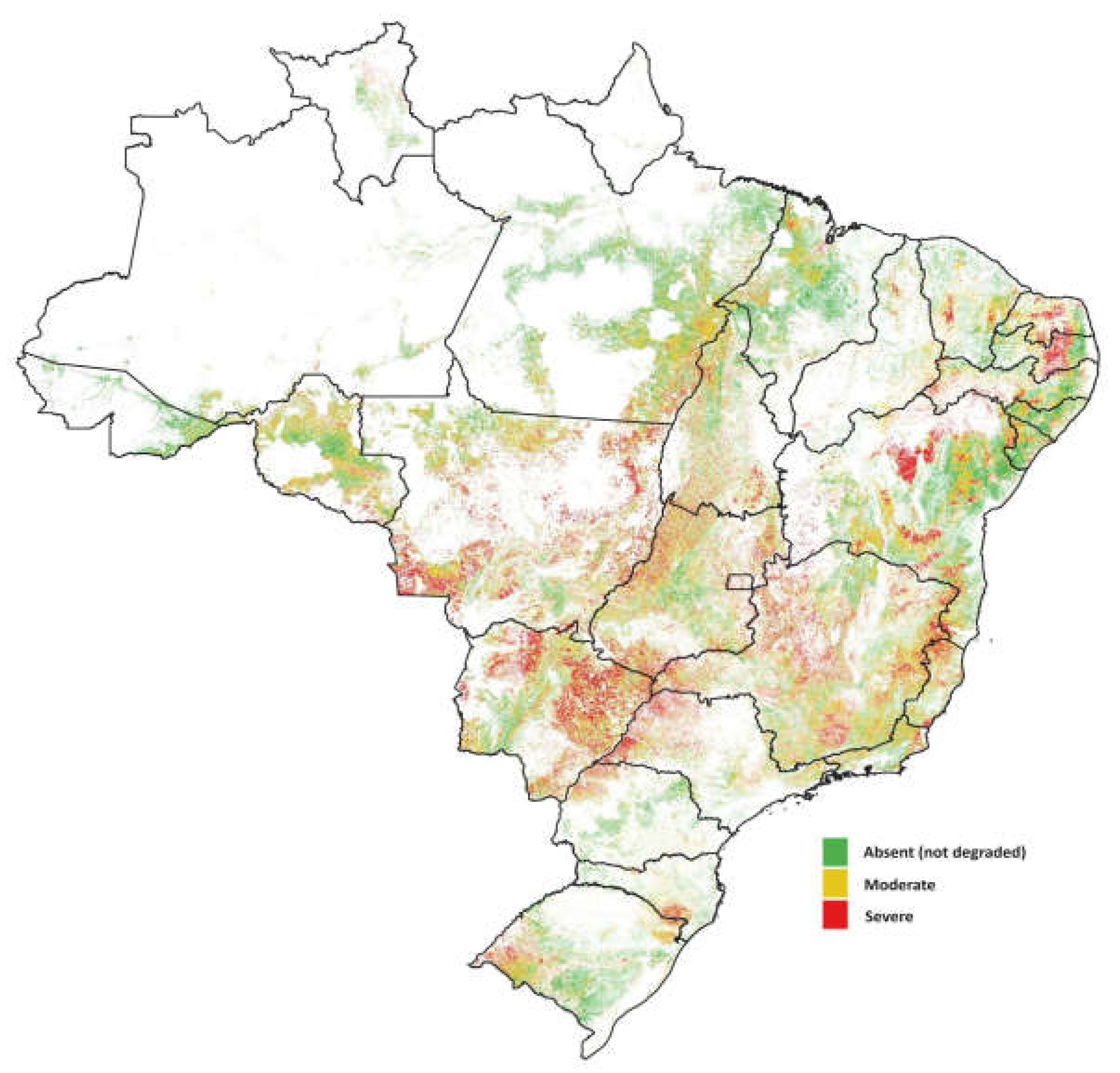

- Santos, C.O.; Mesquita, V.V.; Parente, L.L.; Pinto, A.S.; Ferreira, L.G., Jr. Assessing the wall-to-wall spatial and qualitative dynamics of the Brazilian pasturelands 2010-2018, based on the analysis of the Landsat data archive. (2022) Remote Sensing, 14, 1024. [CrossRef]

- Rede ILPF. (2020) ICLF in numbers, 2020/2021. 14 p. https://redeilpf.org.br/images/ICLF_in_Numbers-Harvest.pdf.

- Brazil. Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply. (2021) Plan for adaptation and low carbon emission in agriculture: strategic vision for a new cycle. Brasilia, DF: MAPA, 25 p.https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/sustentabilidade/agricultura-de-baixa-emissao-de-carbono/publicacoes/abc-english.pdf/view.

- Almeida, R.G.; Andrade, C.M.S.; Paciullo, D.S.C.; Fernandes, P.C.C.; Cavalcante, A.C.R.; Barbosa, R.A.; Valle, C.B. (2013) Brazilian agroforestry systems for cattle and sheep. Tropical Grasslands - Forrajes Tropicales, v. 1, p. 175-183. [CrossRef]

- Barsotti, M.P.; Almeida, R.G.; Macedo, M.C.M.; Laura, V.A.; Alves, F.V.; Werner, J.; Dickhoefer, U. (2022) Assessing the freshwater fluxes related to beef cattle production: a comparison of integrated crop-livestock systems and a conventional grazing system. Agricultural Water Management, v. 269, p. 107665. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). FAOSTAT. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home.

- MAPA. (2023). Governo Federal institui Programa Nacional de Conversão de Pastagens Degradadas. Available at: <https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/ noticias/governo-federal-institui-programa-nacional-de-conversao-de-pastagens-degradadas>. Access: 18 Jan. 2024.

- Bolfe, É.L.; Victoria, D.d.C.; Sano, E.E.; Bayma, G.; Massruhá, S.M.F.S.; de Oliveira, A.F. Potential for Agricultural Expansion in Degraded Pasture Lands in Brazil Based on Geospatial Databases. Land 2024, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LAPIG (2022a). Dados Mapeamento da Qualidade de Pastagem Brasileira entre 2000 e 2020. Disponível em: <https://atlasdaspastagens.ufg.br/assets/hotsite/ documents/metodos/pt/Qualidade%20de%20Pastagem.pdf>. Access 27 de jul 2022.

- LAPIG (2022b). Laboratório de Processamento de Imagens e Geoprocessamento (2022). Atlas das Pastagens. Disponível em: <https://lapig.iesa.ufg.br/p/38972-atlas-das-pastagens>. Access 27 de jul 2022.

- Dias-Filho, M. B. Estratégias para recuperação de pastagens degradadas na Amazônia brasileira. Belém, PA: Embrapa Amazônia Oriental, 2015.

- Carlos, S. M.; Assad, E. D.; Estevam, C. G.; De Lima, C. Z.; Pavão, E. M.; Pinto, T. P. Custos Da Recuperação De Pastagens Degradadas Nos Estados E Biomas Brasileiros. Observatório de Conhecimento e Inovação em Bioeconomia, Fundação Getulio Vargas - FGV-EESP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil, 2022. Available at:https://eesp.fgv.br/sites/eesp.fgv.br/files/eesp_relatorio_pasto-ap3_ajustado_0.pdf. Access: 22 de nov 2022.

- Sekaran, U., Lai, L., Ussiri, D. A. N., Kumar, S., & Clay, S. (2021). Role of integrated crop-livestock systems in improving agriculture production and addressing food security - A review. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 5, 100190. [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, L.A.M., & Balbino, L.C. Políticas de fomento à adoção de Sistemas de Integração Lavoura, Pecuária e Floresta no Brasil. In CFLI: inovação com integração de lavoura, pecuária e floresta (pp. 99-116). Embrapa. (2019).

- Malafaia, G.M. et al. (2019) Sustentabilidade na cadeia produtiva da pecuária de corte brasileira. In: Bungenstab, D.J. et al. (eds.) ILPF: inovação com integração de lavoura, pecuária e floresta. Brasília: Embrapa, 2019. Available at:<http://ainfo.cnptia.embrapa.br/digital/bitstream/item/202386/1/ILPF-inovacao-com-integracao-de-lavoura-pecuaria-e-floresta-2019.pdf> Access: 30 Jan 2024.

- Rodrigues, R.d.A.R., Ferreira, I.G.M., da Silveira, J.G., da Silva, J.J.N., Santos, F.M., da Conceição, M.C.G. (2023). Crop-Livestock-Forest Integration Systems as a Sustainable Production Strategy in Brazil. In: Søndergaard, N., de Sá, C.D., Barros-Platiau, A.F. (eds) Sustainability Challenges of Brazilian Agriculture. Environment & Policy, vol 64. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Arango, J., Ruden, A., Martinez-Baron, D., Loboguerrero, A.M., Berndt, A., Chacon, ´ M., Torres, C.F., Oyhantcabal, W., Gomez, C.A., Ricci, P., Ku-Vera, J., Burkart, S., Moorby, J.M., Chirinda, N., 2020. Ambition meets reality: achieving GHG emission reduction targets in the livestock sector of Latin America. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 4, 65. [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.V.; Almeida, R.G.; Laura, V.A. (2017) Carbon Neutral Brazilian Beef: a new concept for sustainable beef production in the tropics. Brasília, DF: Embrapa, 28 p.https://ainfo.cnptia.embrapa.br/digital/bitstream/item/167390/1/Carbon-neutral-brazilian-beef.pdf.

- Lucchese-Cheung, T.; Aguiar, L.K.; Lima, L.C.; Spers, E.E.; Quevedo-Silva, F.; Alves, F.V.; Almeida, R.G. (2021) Brazilian Carbon Neutral Beef as an innovative product: consumption perspectives based on intentions' framework. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 27:8-9, 384-398. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.G.; Alves, F.V. (2020) Diretrizes técnicas para produção de carne com baixa emissão de carbono certificada em pastagens tropicais: Carne Baixo Carbono (CBC). Campo Grande, MS: Embrapa Gado de Corte, 36 p.

- UNFCCC. (2022). Brazil First NDC - Second update. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/fles/ NDC/2022-06/Updated%20-%20First%20NDC%20-%20%20FINAL%20-%20PDF.pdf.

- IBGE (2021) - Rebanho bovino brasileiro.

- Buainain, A.M.; Garcia Junior, R. Roles and challenges of Brazilian small holding agriculture AGROALIMENTARIA. Vol. 24, Nº 46; enero-junio 2018 (71-87).

- Barreto, P. Policies to develop cattle ranching in the Amazon without deforestation. [n.d.]: Imazon, 2021.

- Cortner, O., Garrett, R.D., Valentim, J.F., Ferreira, J., Niles, M.T., Reis, J., Gil, J., 2019. Perceptions of integrated crop-livestock systems for sustainable intensification in the Brazilian Amazon. Land Use Policy 82, 841-853. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.V., Peres, C.A., Constantino, P.A.L., Santos, B.A., Fischer, E., 2019. Irreplaceable socioeconomic value of wild meat extraction to local food security in rural Amazonia. Biol. Conserv. 236, 171-179. [CrossRef]

- Wetlesen, M.S., Åby, B.A., Vangen, O., Aass, L., 2020. Simulations of feed intake, production output, and economic result within extensive and intensive suckler cow beef production systems. Livest. Sci. 241, 104229. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M. A.; Fairweather, J. R.; Woodford, K. B.; Nuthall, P. L. Assessing the diversity of values and goals amongst Brazilian commercial-scale progressive beef farmers using Q-methodology, Agricultural Systems, Volume 144, 2016, Pages 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Pannell, David & Marshall, Graham & Barr, Neil & Curtis, Allan & Vanclay, Frank & Wilkinson, Roger. (2006). Understanding and Promoting Adoption of Conservation Practices by Rural Landholders. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture - AUST J EXP AGR. 46. 10.1071/EA05037.

- Westbrooke, V. and Nuthall, P. (2017), Why small farms persist? The influence of farmers' characteristics on farm growth and development. The case of smaller dairy farmers in NZ. Aust J Agric Resour Econ, 61: 663-684. [CrossRef]

- EMBRAPA. [N.D.]. Family Farming - Public policies for family farming. Available at: https://www.embrapa.br/en/tema-agricultura-familiar/politicas-publicas Access on 22 Feb. 2024.

- Marta Júnior, G.B., Alves, E.R., Contini, E., 2011. Pecuaria brasileira e a economia dos recursos naturais. Embrapa, Brasília. https://ainfo.cnptia.embrapa.br/digital/bitstre am/item/151530/1/PecuariaBrasileira.pdf. accessed 28 June 2023.

- Molossi, L. et al. Improve Pasture or Feed Grain? Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Profitability and Resource Use for Nelore Beef Cattle in Brazil's Cerrado and Amazon Biomes. Animals, v. 10, n. 8, p. 1-21, 2020.

- Pelicano, S.F., Capdeville, T.G., 2021. Tecnologias poupa-terra. Embrapa, Brasília.

- Balbino, L.C.; Barcellos, A.O.; Stone, L.F. (Ed.). Marco referencial: integração lavoura-pecuária-floresta. Brasília: Embrapa, 2011.130p.

- Garcia, E. et al. Costs, Benefits and Challenges of Sustainable Livestock Intensification in a Major Deforestation Frontier in the Brazilian Amazon. Sustainability 9 (2017), 158.

- J.D.B. Gil, R. Garrett, T. Berger. Determinants of crop-livestock integration in Brazil: Evidence from the household and regional levels, Land Use Policy, Volume 59, 2016, Pages 557-568, ISSN 0264-8377. [CrossRef]

- Carrer, M.J., et al. "Assessing the effectiveness of rural credit policy on the adoption of integrated crop-livestock systems in Brazil." Land use policy 92 (2020): 104468. [CrossRef]

- Cechin, A., Araújo, V. d. S., Amand, L. (2021). Exploring the synergy between community supported agriculture and agroforestry: institutional innovation from smallholders in a Brazilian rural settlement. Journal of Rural Studies, 81, 246-258. [CrossRef]

- Malafaia, G. C., de Vargas Mores, G., Casagranda, Y. G., Barcellos, J. O. J., Costa, F. P. (2021). The Brazilian beef cattle supply chain in the next decades. Livestock Science, 253, 104704.

- de Oliveira Silva, R., Barioni, L., Hall, J. et al. Increasing beef production could lower greenhouse gas emissions in Brazil if decoupled from deforestation. Nature Clim Change 6, 493-497 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.O., Pinto, A.S. Santos, M.P., Alves, B.J.R, Ramos Neto, M.B., Ferreira, L.G. Livestock intensification and environmental sustainability: An analysis based on pasture management scenarios in the Brazilian savanna, Journal of Environmental Management, Volume 355, 2024, 120473. [CrossRef]

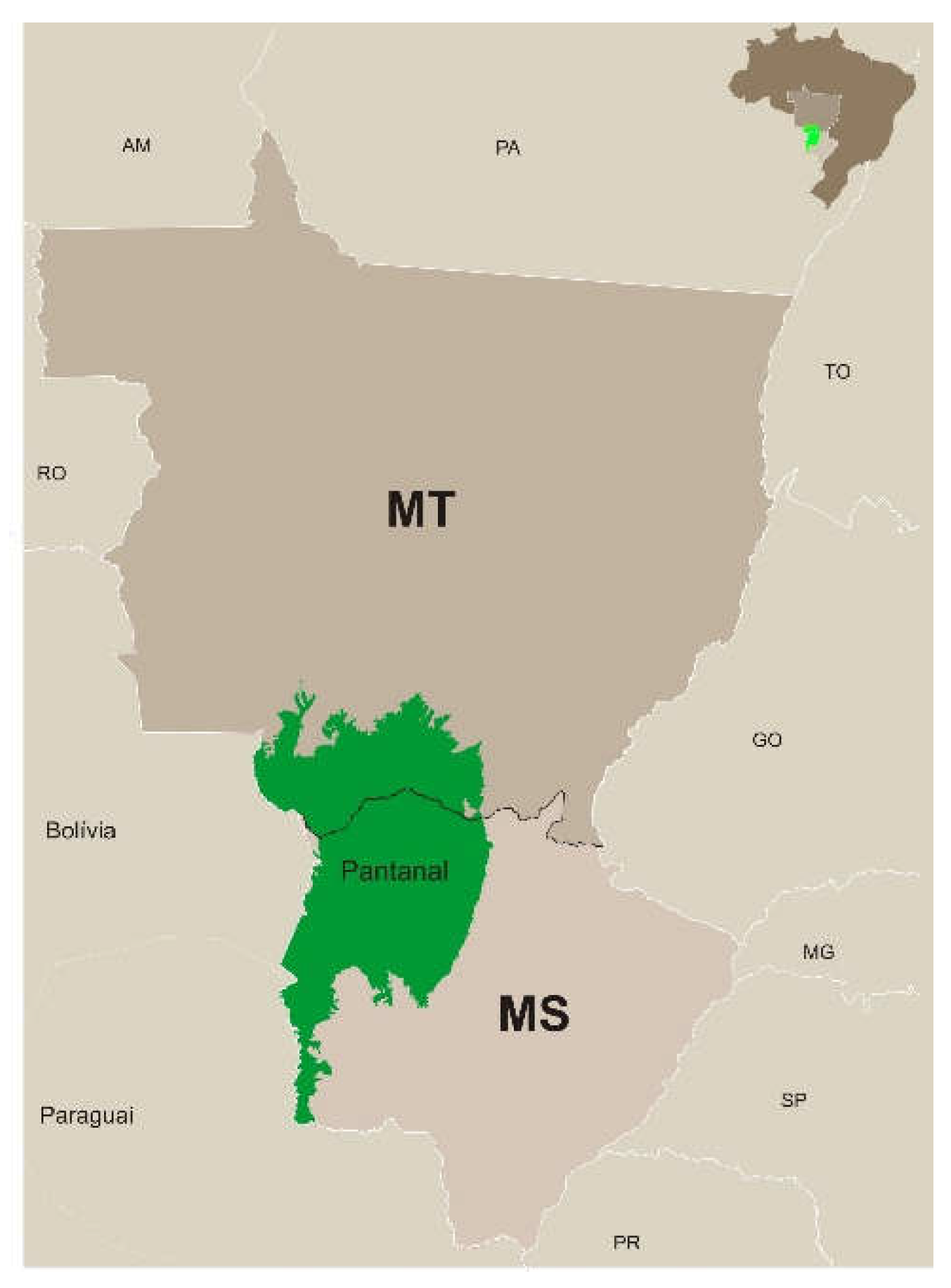

- Mazza, M.C.M.; Mazza, C.A.S.; Sereno, J.R.B.; Santos, S.A.; Pellegrin, A.O. Etnobiologia e Conservação do Bovino Pantaneiro. Corumbá-MS. EMBRAPA, 1994. 61p.

- Guerra, A.; Roque, F.O.; Garcia, L. C.; Ochao-Quintero, J. M. O.; Oliveira, P. T. S.; Guariento, R. D.; Rosa, I. M. D. Drivers and projections of vegetation loss in the Pantanal and surrounding ecosystems. Land Use Policy, v. 91, p.104388, 2020.

- MAPBIOMAS (2022a). Projeto MapBiomas: Coleção (v.6.0) da Série Anual de Mapas de Uso e Cobertura da Terra do Brasil. Disponível em: <https://mapbiomas.org/>. Acess 14 de jun 2022.

- Cadavid Garcia, E. A. Análise técnico-econômica da pecuária bovina do pantanal; sub-regiões da Nhecolândia e dos Paiaguás. Corumbá: EMBRAPA-CPAP, 1985. 92p. (Embrapa-CPAP. Circular Técnica, 15).

- Silva, M. P. Da.; Mauro, R. De A. Utilizacion de pasturas nativas for mamiferos herbivoros en El Pantanal. Archivos de Zootecnia, Cordoba, v. 51, n.193-194, p.161-173, 2002.

- Abreu, U. G. P. De; Carvalho, T. B. De; Santos, M. C. Dos; Zen, S. de. Pecuária de cria no Pantanal: análise de sistemas modais. Corumbá: Embrapa Pantanal, 2019. 28 p. (Embrapa Pantanal. Boletim de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento, 140).

- Pott, E.B.; Catto, J.B.; Brum, P.A.R. Períodos críticos de alimentação para bovinos em pastagens nativas, no Pantanal Mato-Grossense. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira, v.24, n.11, p.1227-1432, 1989.

- Abreu, U. G. P. De; Santos, M. C. Dos; Zen, S. de. Bioeconomics considerations on the modal production system of beef cattle in Pantanal. Brazilian Journal of Development, Curitiba, v. 8, n. 4, p. 28715-28727, 2022.

- Guerreiro, R. L.; Bergier, I.; Mcglue, M. M.; Warren, L. V.; Abreu, U. G. P. De; Abrahão, J.; Assine, M. L. The soda lakes of Nhecolândia: a conservation opportunity for the Pantanal wetlands. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation, v. 17, p. 9-18, 2019.

- Schulz, C., et al. Physical, ecological and human dimensions of environmental change in Brazil's Pantanal wetland: Synthesis and research agenda. Science of the Total Environment, 687 (2019): 1011-1027.

- Abreu, U. G. P De; Bergier, I.; Costa, F. P.; Oliveira, L. O. F. De; Nogueira, E.; Silva, J. C. B.; Batista, D. S. Do N.; Silva Junior, C. Sistema intensivo de produção na região tropical brasileira: o caso do Pantanal. Corumbá: Embrapa Pantanal, 2018. 26 p. (Embrapa Pantanal. Documentos, 155).

- Abreu, U. G. P., Gomes, E. G., Mello, J. C. C. B. S. D., Santos, S. A., Catto, D. F. (2012). Heifer Retention Program in the Pantanal: a study with data envelopment analysis (DEA) and Malmquist index. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia, 41, 1937-1943.

- Oliveira, L. O. F. De; Abreu, U. G. P; Nogueira, E.; Batista, D. S. Do N.; Silva, J. C. B.; Silva Júnior, C. Desmama Precoce no Pantanal. Corumbá: Embrapa Pantanal, 2014. 20 p. (Embrapa Pantanal. Documentos, 127).

- Bergier I., Silva A. P. S., Abreu U. G. P., Oliveira L. O. F., Tomazi M., Dias F. R. T., Borges-Silva J. C. (2019). Could bovine livestock intensification in Pantanal be neutral regarding enteric methane emissions? Science of the Total Environment, 655, 463-472.

- Rodrigues, W. B.; Silva, A. S.; Silva, J. C.B.; Anache, N. A.; Silva, K. C. Da; Cardoso, C. J. T.; Garcia, W. R.; Sutovsky, P.; Nogueira, E. Timed artificial insemination plus heat II: gonadorelin injection in cows with low estrus expression scores increased pregnancy in progesterone/estradiol-based protocol. Animal, v. 13, n. 10, p. 2313-2318, 2019.

| Categories | 2022 |

|---|---|

| Area (million hectares) Herd (1,000 head) |

153.8 202.8 |

| Meat Production (1,000 t CWE) | 10.8 |

| Import (1,000 t CWE) | 80.6 |

| Export (1,000 t CWE) | 3.0 |

| Internal Availability (million t CWE) | 7.8 |

| Population (millions of inhabitants) | 214.1 |

| Availability Per Capita (kg/person/year) | 36.7 |

| CATEGORY OF LAND USE | AREA (ha) | % OF BRAZILIAN AREA (2018) |

|---|---|---|

| Native Vegetation Preserved on Rural Areas | 218,245,801 | 25.6 |

| Full Conservation Units | 88,429,181 | 10.4 |

| Indigenous Peoples Reserves | 117,338,721 | 13.8 |

| Native Vegetation on Unclaimed or Unregistered Areas | 139,722,327 | 16.5 |

| Native Pastures | 68,022,447 | 8.0 |

| Sown Pastures | 112,237,038 | 13.2 |

| Crops | 66,321,886 | 7.8 |

| Commercial Forestry | 10,203,367 | 1.2 |

| Infrastructure, Cities And Others | 29,759,821 | 3.5 |

| TOTAL | 850,280,588 | 100 |

| 1 | 1.00 BRL = 0.1926 USD = 0.1818 EUR |

| 2 | Embrapa leads the National System of Agricultural Research and is publicly funded by the Federal Government. |

| 3 | This mixed-system is known as “semi-intensive finishing”. |

| 4 | In Brazil, the definition of family farms eligible to public policies with subsidized rates are: (i) have a total area of no more than four fiscal modules, which are variable in size according to the region; (ii) rely mostly on family labor; (iii) reach a minimum percentage of income coming from farming; and (iv) manage the farm with the family. |

| 5 | For instance, the “Family Allowance” (Bolsa Familia, in Portuguese) is a public policy targeting rural and urban families whose members earn less than USD 44 per month each. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).