1. Introduction

Over two decades ago, UNESCO (2002) called for education for sustainability by noting, “Improving the quality and coverage of education and reorienting its goals to recognize the importance of sustainable development must be among society’s highest priorities” (p. 9) [

1]. This not only raised the awareness of researchers and educators about keeping our world sustainable through education but also raised an important question to schools and teachers about how to make our education sustainable to support a sustainable society [

2,

3,

4]. Researchers have argued that the current educational paradigm is not oriented toward training students who have the competencies to meet the challenges of a sustainable world that is becoming gradually complex and interdependent [

3,

4]; therefore, educators need to adopt a transformative learning paradigm that emphasizes deep and “critically reflective” learning, an ecological approach (p. 9) [

3], and a sustainable education that is “sustaining, tenable, healthy and durable” (p. 2) [

4]. Rather than focusing on testing and competition this new paradigm highlights the importance of community, engagement, real purpose, participation, ownership, democracy, openness, and environment, and the integration of all these aspects to ensure student success in education [

4,

5].

Under this new paradigm, one key concept that has attracted attention from researchers within the past decade is self-sustained learning (SSL) [

6,

7,

8,

9], which is defined as “the persistent, self-initiated pursuit of expertise development in one’s subject area” (p. 2) [

9]. SSL has been viewed as an important learning outcome in the literature and one important component of effective teaching, which can transform passive student learning into active pursuit of knowledge in and outside of their usual classroom. It also has similarities with other concepts of learning, such as self-regulated learning and lifelong learning [

9,

10,

11]. Previous studies have found that engaging students in courses that are carefully designed in the subject area, project-based learning, fluency-building, and communicative activities facilitates SSL [

7]. Teaching strategies such as inquiry-based scaffolding tasks, classroom dialogues, and critical reflections can also foster students’ SSL [

9].

Despite the significance of SSL in education, none of the studies to date have examined it with college students who study English as a second language (ESL) in China. As one of the languages that are spoken the most around the world, English has been placed a high value in China, with 400 million English learners. Most students in China started to study English in school in the third grade. English is also a compulsory course for non-English major undergraduate students in the first two years at 3-year or 4-year colleges and for non-English major graduate students in the first year of their post-graduate studies. Many studies have examined Chinese students’ motivation and attitudes toward learning English [

12], beliefs about learning English [

13], self-regulated learning strategies, self-efficacy beliefs [

14], and identity construction [

15]. However, it remains unknown how students engage in SSL or continue to study English outside of their classes when they are taking English classes and whether they maintain the intention to learn English when they do not enroll in English classes.

Additionally, none of the studies to date have investigated the predictors of SSL in the context of ESL. The literature has suggested that individual factors, such as intercultural communicative skills, language mindset, and positive L2 self, were significant predictors of L2 outcomes, including L2 proficiency, L2 self-efficacy, and intention to continue to learn English [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. This study seeks to study the relationships between these variables and SSL through a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach, aiming to gain an in-depth understanding of SSL and its predictors. The findings of this study will provide insights into college students’ English learning not only in the Chinese context but also in the ESL or EFL context.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Self-Sustained Learning

The concept of self-sustained learning (SSL) was discussed by Barron in 2006 when she was studying adolescent’s development of technological fluency in and outside of school contexts [

6]. Grounded in sociocultural and activity theory [

22,

23], SSL focuses on utilizing physical or virtual environments to provide learning opportunities for learners. Compared with the attention paid to contextual factors in the framework, the concept of SSL focuses on the key role that individuals play in their development, for instance, their temperament and personality shape how people respond to them. It also aligns with theories about individuals’ identity development [

24] and interest development [

25]. According to identity development theories, learning that transforms identity is different from everyday learning and makes people think they can become someone new. Interest is also developed from a self-initiated learning process that seeks opportunities for new activities, knowledge, and relationships. Under these theoretical perspectives, SSL describes a type of learning that is directly derived from the self-initiatives of the learners, which not only shows their intrinsic interest in a subject area but also motivates them to seek knowledge and expertise independently and persistently outside the spaces where they usually acquire knowledge [

6,

7,

9].

Self-sustained learning was regarded as a type of effective learning that facilitates students’ active learning and makes true learning happen. It enables students to acquire, understand, retain, and apply knowledge on their own, leading to mastery of the concepts and theories and development of core competencies, including problem solving, creativity, and critical thinking [

26,

27,

28]. With the ability to learn in a self-sustained way, students who are often treated as passive learners in the classroom are empowered to take control of their learning, think independently, and actively interact with their classmates. They are also willing to extend the in-class learning time to the spaces outside the classroom and eventually use both formal and informal learning opportunities to acquire knowledge and skills [

6,

27,

29].

Self-sustained learning shares similarities with other types of learning, such as self-regulated learning and lifelong learning. Both SSL and self-regulated learning emphasize the key role of “self”, or the active role of individuals, in the process of learning. By contrast, both SSL and lifelong learning highlight the importance of a long time in the learning process [

9]. There are also differences among these types of learning. Compared with self-regulated learning which focuses on using strategies to regulate, monitor, and adjust individual cognition, motivation, and behavior to achieve learning goals [

11], SSL focuses on using efforts and strategies to learn continuously within a long time to achieve the learning goals. On the other hand, lifelong learning emphasizes the importance of continuous learning throughout an individual’s life, especially after the individual completes formal education [

10], while self-sustaining learning can refer to learning at any time in an individual’s life.

Compared with the research on self-regulated learning and lifelong learning, there has been much less research on SSL. Although SSL can be the antecedent of many learning outcomes, such as student academic achievement, it has often been considered a crucial high-level learning outcome in the current literature [

9,

30]. Barron (2007), for instance, designed a computer science curriculum based on a new school-university partnership as an intervention and concluded that the curriculum effectively enriched students’ learning ecologies and inspired their SSL [

7]. Yang (2015) examined the existing literature on SSL, analyzed possible issues that teachers usually encounter in nurturing students’ SSL in the classroom, and suggested three strategies to address these issues, including inquiry-based scaffolding tasks, engaging classroom dialogues, and engaged critical reflections [

9]. Checketts (2019) reflected on his teaching philosophy in teaching English as a second language and reviewed the literature on teaching communication strategies and the pragmatics of greetings in second language classes, aiming to foster students’ SSL [

8]. Yet, none of these studies have paid attention to what variables predict SSL.

2.2. Intercultural Communicative Skills

Intercultural communicative skills are one aspect of intercultural competence (ICC), which has been viewed as an important skill in higher education [

31] due to globalization and increasingly interconnected interactions in the world [

32]. ICC can be defined as “the ability to communicate effectively in cross-cultural situations and to relate appropriately in a variety of cultural contexts” (p. 149) [

33]. Individuals with high levels of ICC can conscientiously engage in self-reflection to deepen their understanding of cultural differences and similarities, adapt their attitudes and actions thoughtfully in diverse intercultural settings, and demonstrate a capacity for flexible and effective interactions across cultures [

32].

In the context of language learning, intercultural competence highlights the importance of cultural understanding and intercultural awareness in language acquisition [

34]. It can positively predict language learners’ language skills and proficiency [

35,

36,

37]. For example, Young et al. (2013) found a strong association between ICC and language proficiency among 108 non-UK postgraduate students [

37]. Fathi et al. (2023) investigated the effects of foreign language enjoyment (FLE), ideal L2 self, and ICC on L2 willingness to communicate (WTC) among EFL learners in Iran and found that all the variables of interest (i.e., FLE, ideal L2 self, and ICC) directly predicted L2 WTC [

38].

The construct of ICC has been studied in different cultures [

39,

40,

41], including China, where scholars have conceptualized, defined, and developed the measures of ICC in the Chinese context [

42,

43,

44,

45]. Wu et al. (2013), for instance, defined ICC from six aspects: knowledge of self, knowledge of others, attitudes, intercultural communicative skills, intercultural cognitive skills, and awareness [

46]. Among these aspects, intercultural communicative skills that focus on skills individuals use in communications across different cultures are the most important aspect of ICC because the concept of ICC originated from the notion of communicative competence [

41]. These skills are viewed as one of the ultimate goals of students’ English learning [

47,

48] and the key skills of students who learn English as a second or foreign language [

49,

50,

51].

Past research has shown that the intercultural communicative skills of EFL learners had a positive impact on their language learning motivation, willingness to communicate, and language and intercultural competence [

38,

52,

53]. For instance, Tran and Duong (2018) implemented a 13-week intercultural language communicative teaching model with EFL learners in Vietnam and found significant improvement in the learners’ language and intercultural competence [

53]. Moreover, a few studies have found that intercultural competence is positively related to language learners’ L2 self-concept [

16,

17,

54]. Kanat-Mutluoglu (2016) examined the relationships among intercultural communicative competence, academic self-concept, and ideal L2 self in 173 college students in Turkey [

17]. The findings revealed a strong relationship between ICC and academic self-concept and a moderate association between ICC and the ideal L2 self. However, few studies have explored whether intercultural competence, particularly intercultural communicative skills, could predict college students’ sustained language learning. It is still unclear if the impact of intercultural competence on L2 self-concept will further influence language learners’ long-term learning.

2.3. Language Mindset

Developing from implicit theories of intelligence, mindset theories account for resilient and destitute patterns of responses to challenges and setbacks [

55,

56]. Dweck (2006) outlined the two fundamental types of mindsets as either fixed or growth-oriented. Individuals with a growth mindset believe that skills can be acquired and enhanced through committed effort and perseverance [

55]. Consequently, they focus on their capacity for change, fostering the pursuit of resilient and adaptive objectives. On the contrary, those with a fixed mindset perceive abilities as innate and unalterable, which drives individuals toward competitive and maladaptive goals [

57,

58].

When it comes to language learning, Lou and Noels (2016) proposed a concept called “language mindset”, which focuses on investigating people’s beliefs about language learning [

19]. The language mindsets comprise three key components: general language intelligence beliefs that focus on the beliefs regarding whether language intelligence is fixed or malleable; second language aptitude that refers to whether the ability to learn a language is considered changeable through effort or deemed fixed; beliefs related to age sensitivity and language learning that addresses whether language learning ability could be cultivated up to a certain age and remained fixed thereafter. Consistent with Dweck’s (2006) framework [

55], language mindsets are also structured within two aspects: fixed language mindset and growth language mindset [

19].

Studies have indicated that language mindset plays a crucial role in language learning. Specifically, a growth language mindset is positively related to language learners’ learning goals, engagement, and achievement [

19,

20,

21]. For example, Lou and Noels (2016) examined if language mindsets influenced language learners’ goal orientation and, in turn, affected their intention to continue learning the language [

19]. The results showed that learners who hold a growth language mindset endorsed learning goals more strongly regardless of their perceived language competence, which in turn reported a more persistent intention to keep learning the language.

In addition, although multiple studies have suggested that students with a growth mindset are more likely to have positive self-concepts in math [

59,

60], the findings have not reached a consensus in the language learning setting. Some studies indicate a positive connection between language learners’ growth mindset and their self-concept [

61]. In contrast, others argue that students’ mindsets are not significantly correlated with self-concept [

59]. Therefore, additional research is required to examine whether students’ language mindsets can influence their self-concept, which further predicts their intention to keep learning the target language.

2.4. Positive L2 Self

Brown (2004) defines self-concept as a “process of thinking about one’s own experiences and behaviors, then contemplating one’s thought processes, and the need for self-acceptance and ego protection” (p. 123) [

62]. In other words, the self-concept reflects the perception and beliefs that individuals hold about themselves [

63]. When examining self-concept within educational contexts, scholars suggest that academic self-concept refers to individuals’ understanding and views of their abilities in academic situations [

64]. A considerable amount of research has shown that students’ academic self-concept is associated with their learning behaviors and achievement [

65,

66,

67]. For example, Chen et al. (2022) conducted an empirical study to explore the impact of self-concept and self-efficacy on English language learning outcomes [

66]. The findings indicated that self-concept can directly and indirectly influence English learners’ learning outcomes through self-efficacy.

More recently, scholars have suggested that students’ academic self-concept might vary in different subjects [

68]. For example, a student may affirm having high capability in math but lower aptitude in languages. Accordingly, to further understand students’ self-concept in language learning, Lake (2015) developed a construct of positive L2 self, which organizes various constructs that relate to positive self-constructs and motivation in the L2 field. Lake (2015) further proposed three relevant but distinct subdimensions of positive L2 self, which include interest in L2 self, harmonious passion for L2 learning, and mastery of L2 goal orientation. Interest in L2 self refers to the tendency to perceive the learning of a second language as fascinating and enjoyable; harmonious passion for L2 learning indicates a strong inclination toward activities related to language that are favored or loved; mastery of L2 goal orientation is characterized by an individual’s purpose that focuses on achieving substantial progress in learning [

18].

Multiple studies have found that positive L2 self is positively related to various aspects of English learning, including academic resilience in English learning, L2 self-efficacy, and L2 proficiency [

18,

69]. For example, Lake (2015) explored the relationship between positive L2 self, L2 self-efficacy, and L2 proficiency among 539 college students [

18]. The results indicated that positive L2 self significantly predicted L2 self-efficacy, which in turn influenced L2 proficiency. However, the relationship between positive L2 self and students’ self-sustained English learning is still under investigation.

3. The Current Study

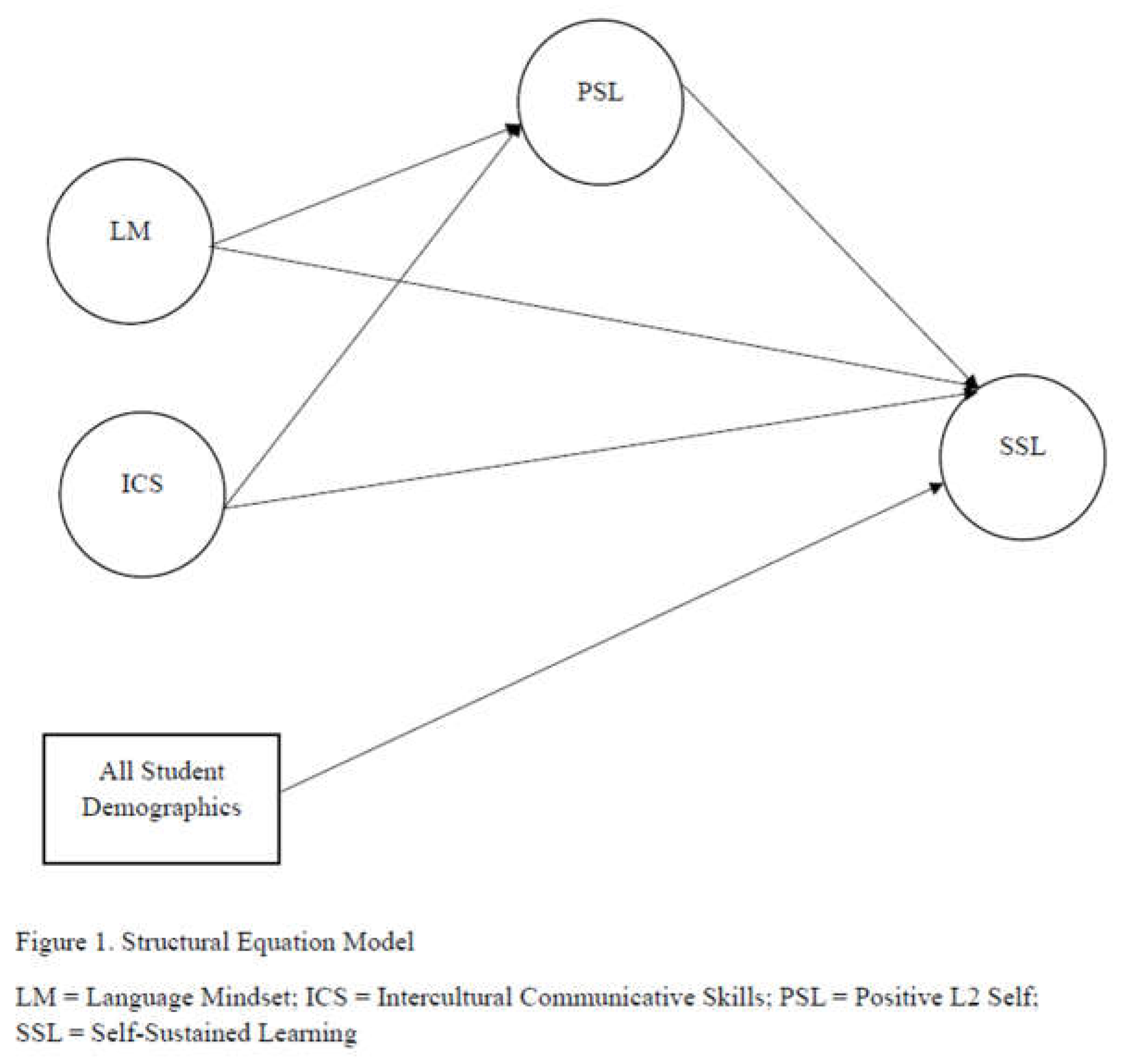

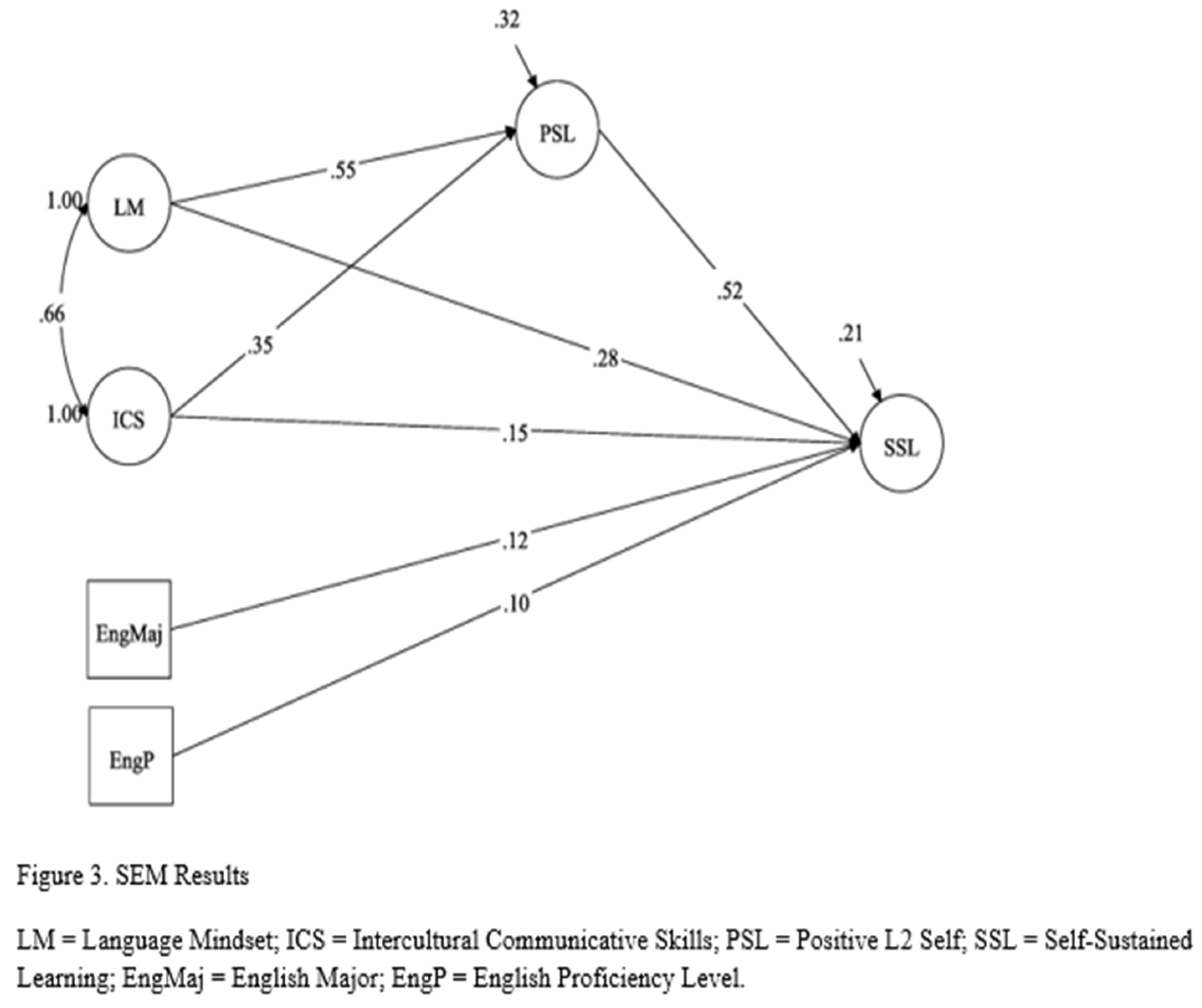

Based on the above literature review, we created a statistical model (see Figure 1) about the relationships of the variables of interest. In the model, language mindset (LM) and intercultural competence (ICC) are two exogenous variables, positive L2 self is the mediator, and SSL is the endogenous variable. All student demographic variables, such as their sex and grade, were included in the model as control variables (see 4.2.5 section). We aimed to address the following research questions in the current study:

RQ1. Do Chinese ESL learners engage in strong self-sustained English learning and have language mindsets, positive L2 self, and intercultural communicative skills?

RQ2. Do language mindset and intercultural communicative skills of Chinese ESL learners significantly predict their positive L2 self?

RQ3. Do language mindset, intercultural communicative skills, and positive L2 self of Chinese ESL learners directly predict their self-sustained English learning?

RQ4. Does the language mindset and intercultural communicative skills of Chinese ESL learners indirectly predict their self-sustained English learning through positive L2 self?

4. Methods

4.1. Participants

Participants (N = 1,238) were mainly recruited through the assistance of their English teachers from four universities in Chongqing, China that represented different Chinese university types—a flagship comprehensive university, a normal university, a science and technology university, and a private university. Most of the participants (68.7%) were female, undergraduate students (65.3%), and non-English majors (75.9%). Over half of the participants (61.1%) have studied English as a second language for 5-10 years (see

Table 1).

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Language Mindset

Language mindset was measured by Wang et al.’s (2021) Chinese version of the Language Mindsets Inventory, which was originally developed by Lou and Noels (2017) and has been popularly adapted in studies focusing on English language learning. Previous studies have shown good reliability and validity of this instrument in different languages [

21,

71,

72], including the Chinese version [

70]. The instrument has 9 items, and 3 items are designed to measure each of the three dimensions— second language aptitude beliefs, age sensitivity beliefs about language learning, and general language intelligence beliefs. Example items include: “You can always change your foreign language ability”; “In learning a foreign language, if you work hard at it, you will always get better”. All items were based on a 5-point Likert scale (1—Strongly Disagree, 5—Strongly Agree). Cronbach’s alpha was .94 for all 9 items, and .83, .86, and .88 for items measuring three dimensions in this study.

4.2.2. Intercultural Communicative Skills

Intercultural communicative skills were measured by a section on the same construct in the Assessment of Intercultural Competence of Chinese College Students (AIC-CCS), which was developed by Wu et al. (2013) for Chinese college students in the Chinese context and has been widely used in China [

73,

74,

75]. Previous studies have shown that the instrument has good reliability and validity. There are 9 items that measure intercultural communicative skills. Participants are asked to rate themselves about their skills based on a 5-point Likert scale (1—Very Low; 5—Very High). Example items include “the skill of consulting with foreigners when misunderstandings occur”; “the skill of treating foreigners politely”. Cronbach’s alpha of the 9 items in this study was .94.

4.2.3. Positive L2 Self

Positive L2 self was assessed by Wang’s (2023) Chinese version of Lake’s (2015) measure, which has 21 items. Seven items are designed to measure one of the three dimensions: interest in L2 self, harmonious passion for L2 learning, and mastery of L2 goal orientation [

69]. Previous studies have shown good reliability and validity of this instrument. All items were based on a 5-point Likert scale (1—Definitely Not True Of Me; 5—Definitely True Of Me). Example items include “English lessons are enjoyable”; “I am passionate about learning English”. Cronbach’s alpha was .98 for all 21, .96, .95, and .95 for the items measuring three dimensions in this study.

4.2.4. Self-Sustained English Learning

The Self-sustained English learning scale was developed by authors in this study based on the literature review on SSL [

6,

7,

8,

9]. For instance, according to Barron (2006), SSL processes include searching for text-based informational sources, creating new interactive activities, seeking structured learning opportunities, and using media [

6]. The scale consists of two components: short-term self-sustained English learning and long-term self-sustained English learning. The former component has 7 items that are related to students’ SSL when they are taking English classes. All items were based on a 5-point Likert scale (1—Strongly Disagree, 5—Strongly Agree). Example items include “I keep learning English after class”; “I practice English with my peers in my after-class time”. The latter component has 4 items that are related to students’ self-sustained English learning after they complete English classes or after they graduate. Example items include “I will continue to learn English in my future jobs”; “I will continue to learn English after I graduate from college”. This instrument went through a few procedures to ensure its reliability and validity before it was used in this study, such as expert reviews to provide validity evidence based on content, cognitive interviews to provide validity evidence based on response processes, and Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to provide validity evidence based on internal structure. For instance, in the original development and validation study with 300 Chinese college students who learn English as a second language, EFA results confirmed the two factors in the original conceptualization of this measure, and Cronbach’s alpha of the 11 items was .89. Cronbach’s alpha was .94 for all 11 items and items measuring the two components in this study.

4.2.5. Demographic Background

Students’ demographic background was measured by indicating their sex, grade, school, their self-evaluation of English proficiency level, the length of learning English, the frequency of being in contact with English native speakers, and whether they are undergraduate student, English major, or have been abroad.

4.3. Procedure

The study was approved by the Institutional Research Board at the first author’s institution and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. The survey that included all the measures and the demographic questions was administered at

www.wjx.cn, the most widely used, secure online survey platform in China. Participants first read the information statement about the study, signed the informed consent, and agreed to participate in the study. They then completed all the measures and the demographic questions. No other identifying information was collected.

4.4. Data Analysis

Before any analysis was conducted, data was checked for normality and outliers, and the normality assumption was found not violated. The main analysis method we used was latent variable Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) which can examine both measurement and structural models simultaneously [

76] and provide an unbiased estimate of direct and indirect effects [

77]. Two steps were carried out based on SEM researchers’ recommendations [

78,

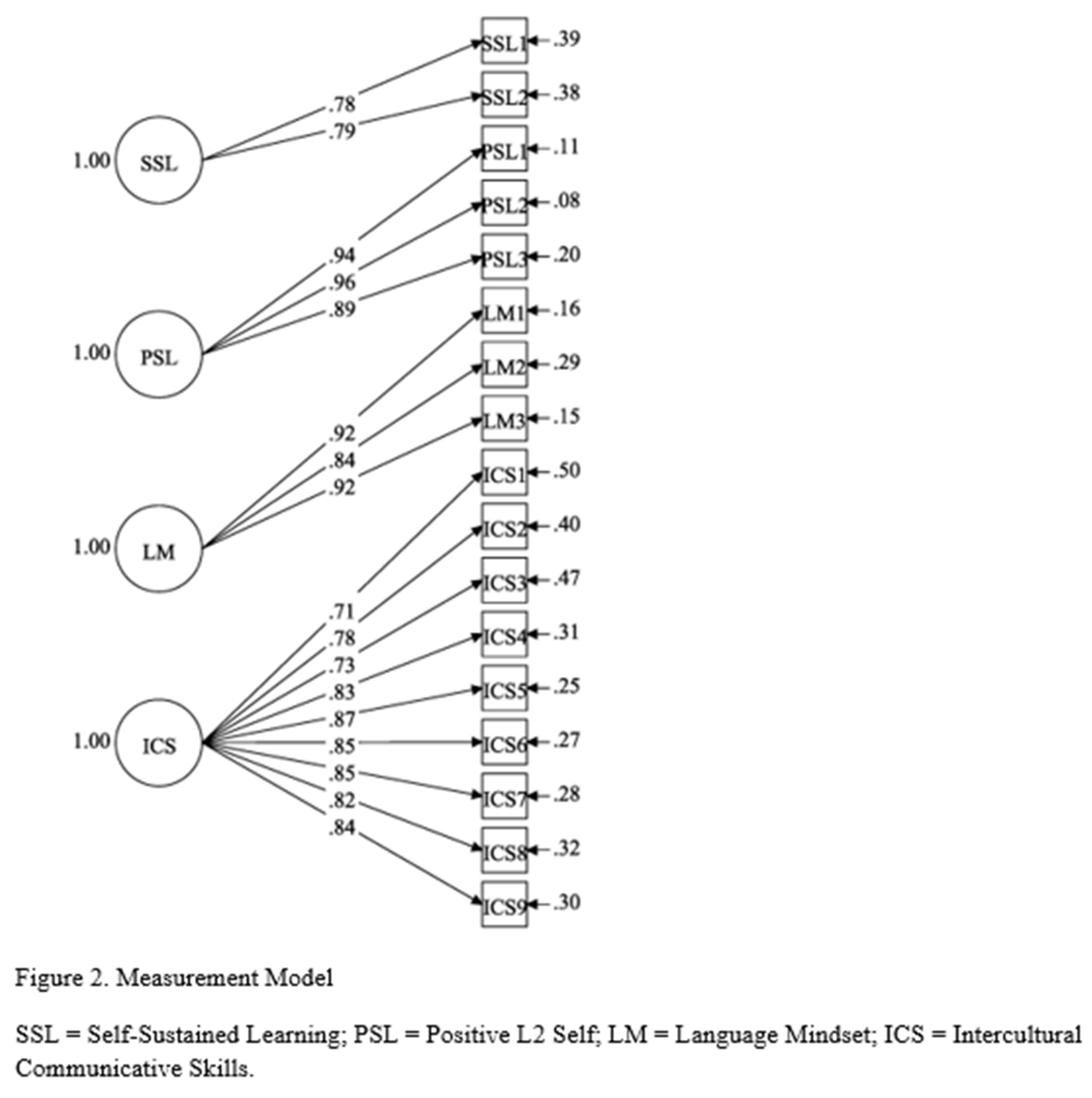

79]: the first step was a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) of all the latent variables, which aimed to ensure sufficient construct validity of the measurement model (see Figure 2); the second step was SEM, which aimed to understand the structural relationships among the four latent variables (see Figure 1). In this SEM model, language mindset and intercultural communicative skills were treated as exogenous variables, positive L2 self was the mediator, and self-sustained English learning was the endogenous variable. Students’ demographic information was used as control variables, which included sex, degree, major, self-rated English proficiency level, length of English learning, going abroad, or contact with foreigners.

The main analyses of CFA and SEM were performed in Mplus 8.10 [

80]. Parceling was employed in the analyses to create parceled items as indicators of three latent constructs: language mindset, positive L2 self, and self-sustained English learning. More specifically, parcels were created as the average of items that measure each dimension of the construct. For instance, two parcels were formed for self-sustained English learning that corresponds to short-term and long-term self-sustained English learning. Despite a few weaknesses of parceling, this approach has many advantages, such as parceled items leading to simpler models and better fit [

81,

82]. In interpreting the results of CFA and SEM, we used model fit indices of Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). A model is often considered excellent if CFI and TLI are .95 or above, RMSEA is .06 or below, and SRMR is .08 or below [

83,

84]. The STDYX function was used to obtain all standardized coefficients. The bootstrap Confidence Interval method was used to test indirect effects, with 5,000 bootstraps because it can control Type I error while yielding an accurate value [

85].

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Descriptive statistics of the parceled items of language mindset, positive L2 self, and self-sustained English learning, and all 9 items of intercultural communicative skills were reported in

Table 2. Overall, students had a strong language mindset, with a slightly higher level of beliefs related to age sensitivity when learning English than their beliefs related to second language and general language intelligence. Students’ positive L2 self was also strong, and their scores in the three components were comparable. Additionally, students scored higher in long-term self-sustained English learning than in short-term self-sustained English learning. Among the 9 items that measure intercultural communicative skills, students rated the highest their ability to politely treat foreigners but rated the lowest their ability to negotiate with others. Correlations of the four latent variables were also calculated (see

Table 3). The results indicated that all variables were significantly correlated, and the correlations ranged from .34 to .50.

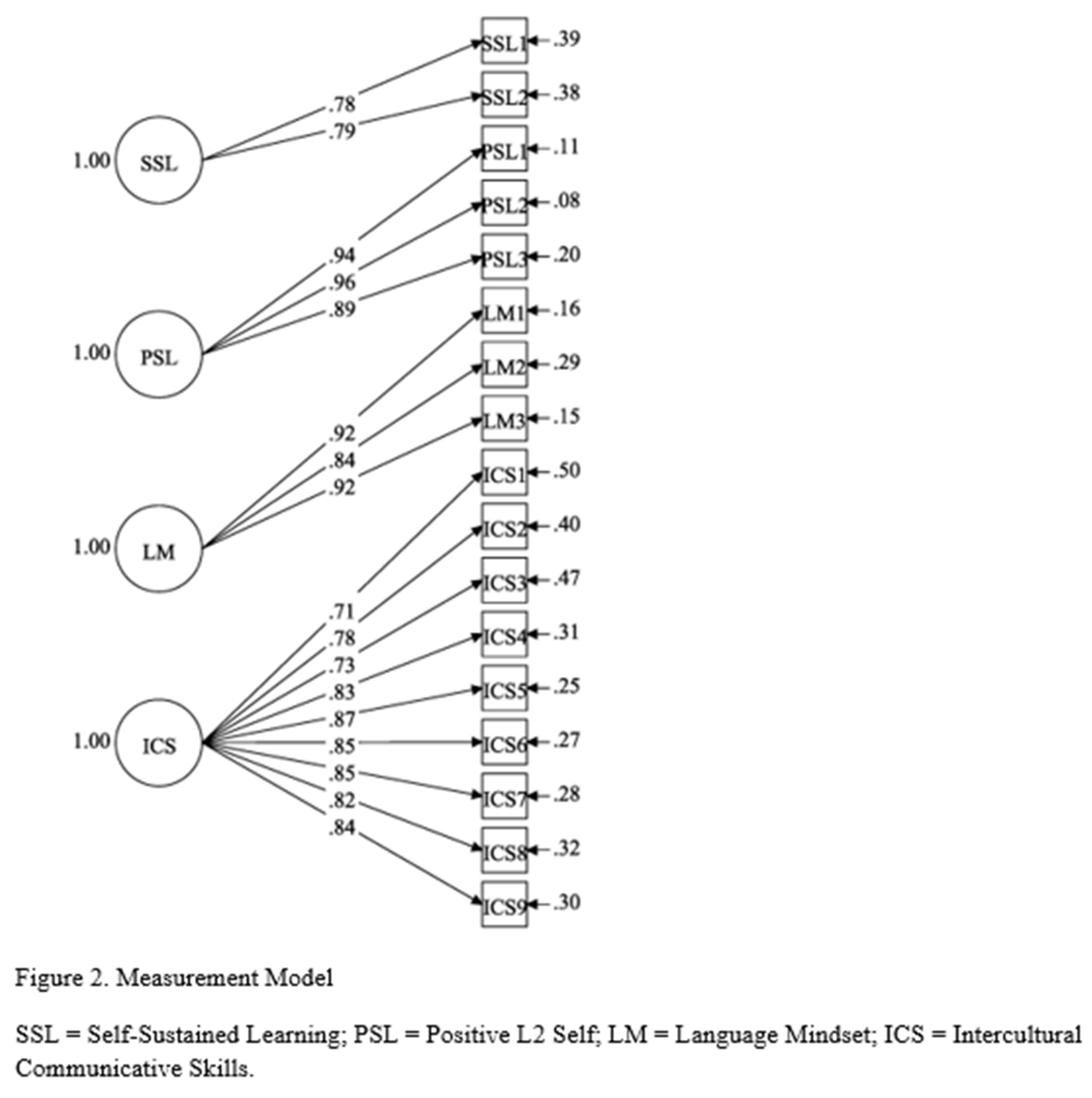

5.2. CFA

The CFA model with four latent variables showed a good fit: CFI: .90, TLI: .88, RMSEA: .12, 95% CI [.118, .127], SRMR: .05. To account for the correlations of a few indicators in intercultural communicative skills measure, we added their correlated residuals in the model, such as ICC1 and ICC2, ICC1 and ICC3. This significantly increased the model fit: CFI: .95, TLI: .94, RMSEA: .087, 95% CI [.082, .092], SRMR: .05. All factor loadings were significant and strong, ranging from .71 to .96 (see Figure 2).

5.3. SEM

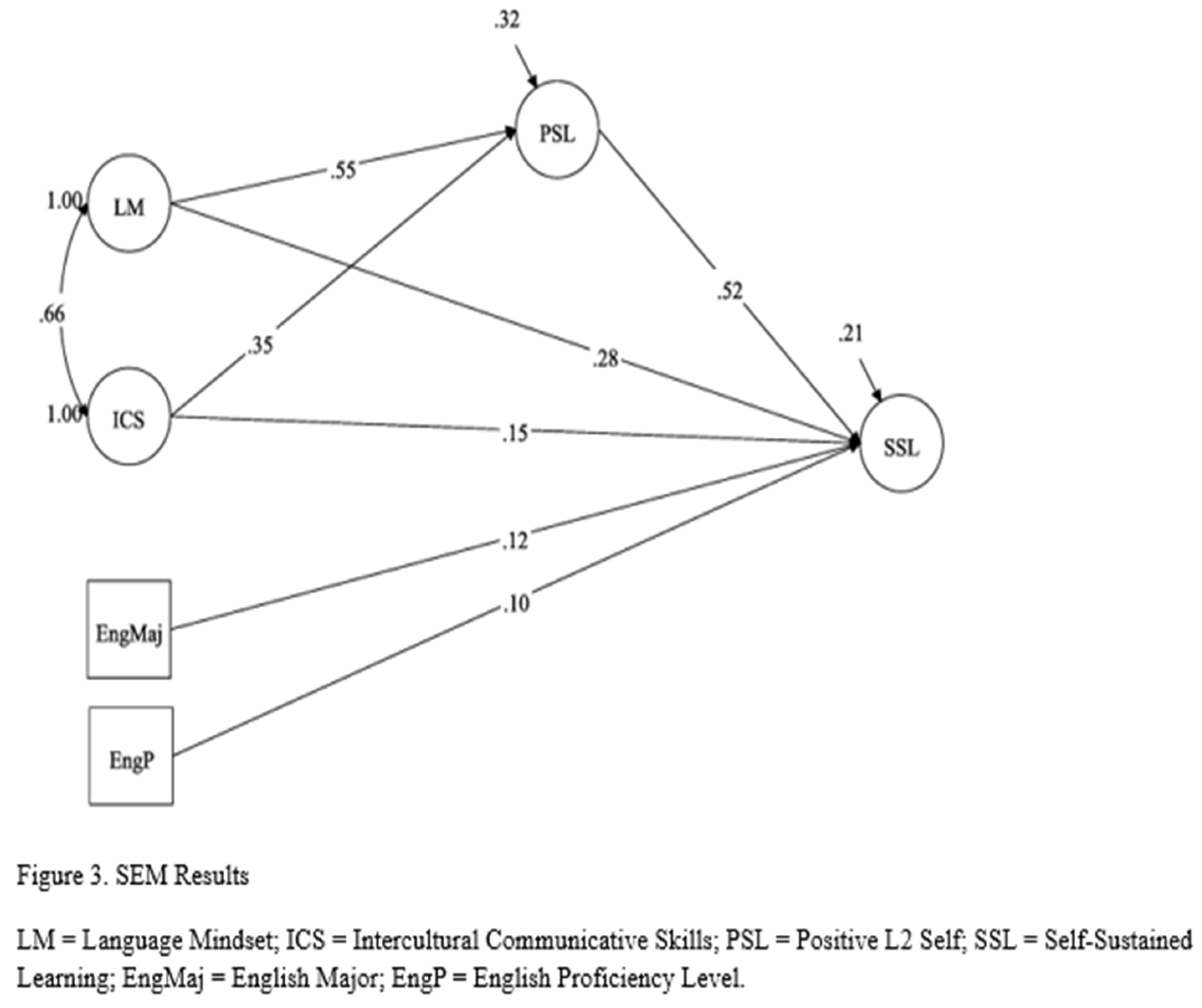

Language mindset and intercultural communicative skills were both significant and positive predictors of positive L2 self. The former variable (β = .55, p < .001) had a stronger effect than the latter one (β = .35, p < .001). These two variables explained a large portion (68.1%) of the variance in positive L2 self. They and positive L2 self all had significant direct effects on self-sustained English learning. Among the three variables, positive L2 self had the strongest effect (β = .52, p < .001), followed by language mindset (β = .28, p < .001) and intercultural communication skills (β = .15, p = .001). Language mindset and intercultural communication skills also had significant indirect effects on self-sustained English learning through positive L2 self (see Figure 3). The indirect effect of language mindset was .29, p < .001, 95% CI [.21, .36], which was stronger than that of intercultural communication skills (β = .19, p < .001, 95% CI [.15, .25]). Only two control variables—students being an English major (β = .12, p < .001) and their self-rated English proficiency level (β = .10, p = .001)—were significant predictors of self-sustained English learning, and their effects were small and comparable. This model with direct and indirect effects and the effects of the two control variables explained a very large part (79.2%) of the variance in self-sustained English learning.

6. Discussion

This study is the first empirical study to examine self-sustained learning and its predictors among Chinese college students who study English as a second language. The findings indicated that students scored higher in long-term self-sustained English learning than in short-term self-sustained English learning, suggesting a strong intention to continue to learn English after they complete their compulsory English courses and after they graduate from college. This may be because English is always considered an important language in Chinese society, and many companies or government units require their employees to be proficient in English. Furthermore, given that many college students in China consider English a tool that can be used in their work and other aspects of life, such as travel [

12], it is not surprising to find that they still want to keep their English after they complete their English classes or even after they graduate from college.

Further, this study showed that Chinese students had an overall strong language mindset and positive L2 self, which is consistent with previous findings. For instance, Liu (2007) found that the majority of college students in China had moderately or strongly positive attitudes toward English learning [

12]. The finding that students had a slightly higher level of beliefs related to age sensitivity than their beliefs related to second language and general language intelligence suggests that students prioritize the importance of effort in learning English rather than believing that their English learning is limited by age. This is in line with the Chinese culture, which espouses the significance of effort in learning [

86]. This study indicated that Chinese college students felt most confident in their ability to politely treat foreigners but felt least confident in their ability to negotiate with others. Politeness in China is a highly valued quality, and being polite in English may be easily achieved by using words like “Please” or “Thank you”. In contrast, negotiating with others, in its own right, is more challenging than simply talking with others or treating others politely because it involves not only language competencies but also strategies to convince others.

This study demonstrated that language mindset and intercultural communicative skills both significantly predicted positive L2 self, which also significantly predicted self-sustained English learning. These findings are consistent with previous ones that indicated language mindset, intercultural communicative skills, and positive L2 self were significant, positive predictors of many L2 learning outcomes, including the intention to continue to learn English and L2 proficiency [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. In this study, long-term self-sustained learning was similar to the intention to continue to learn English. It is interesting to learn that language mindset was a stronger predictor of positive L2 self than intercultural communicative skills, while positive L2 self was a stronger predictor of self-sustained English learning than language mindset. These suggest that students’ beliefs about language play a more important role than their skills of communicating with others in forming students’ positive attitudes toward learning English as a second language. In contrast, students’ positive attitudes toward learning English and about themselves are more important than their beliefs about language in facilitating short-term and long-term self-sustained learning in English. In either case, teachers should pay attention to fostering students’ positive attitudes toward learning English and their beliefs about English besides training students’ intercultural communicative skills.

This study further found that students being an English major and their self-rated English proficiency level significantly predicted self-sustained English learning. Previous studies treated English proficiency level as a dependent variable and showed that language mindset, positive L2 self, and intercultural communicative skills were predictors of English proficiency level [

18,

37,

53,

69]. This study suggests that the relationship between English proficiency level and other L2 learning outcomes may be bidirectional. On the other hand, it is not surprising to find that being an English major was a significant predictor of self-sustained English learning because it not only means spending more time and effort studying English than a non-English major when students are taking English classes but also means using English more often after students graduate from college than non-English majors, mainly in their future jobs.

The most interesting finding of this study was that both language mindset and intercultural communicative skills had significant indirect effects on self-sustained English learning through positive L2 self. This suggests that teachers can improve students’ self-sustained English learning by improving students’ language mindset and intercultural communicative skills but cultivating students’ positive L2 self may be a more effective strategy for increasing students’ self-sustained English learning. The significant role that positive L2 self plays in L2 English learning has been consistently reported in many previous studies [

18,

69]. Because the positive L2 self has three components: interest in L2 self, harmonious passion for L2 learning, and mastery of L2 goal orientation, teachers can focus on these aspects in nurturing students’ positive L2 self in English classes. Nevertheless, all the direct and indirect effects in the model explained about 80% of the variance in self-sustained English learning, supporting a very strong SEM model.

6.1. Limitations

Despite the interesting findings, this study is still limited in the following aspects. First, the sample was a convenience sample, and most of the colleges sampled were from the same area. Although the type and size of these colleges and students’ characteristics in these colleges were considered in the sampling, the sample used in this study was not representative of college students in China, which limited the generalizability of the findings in this study to other contexts. Future studies can use a more representative sample in China and other countries where students learn English as a second language to see if the same results are replicated. Second, this study used a cross-sectional design. We intended not to make any causality claims about the relationships examined in this study, therefore, any such claims should be cautioned or avoided. Future studies can use longitudinal study designs to examine the cause-and-effect relationships among all the examined variables. Third, although we collected data from both English and non-English majors, we did not analyze the data in separate samples. Future studies can use multiple-group SEM to examine the relationships among the same variables in English major and non-English major samples.

7. Conclusions

This study is the first one in the literature to examine self-sustained learning and its predictors among a group of Chinese college students within the context of learning English as a second language. The findings showed that students scored higher in long-term self-sustained English learning than in short-term self-sustained English learning and that they had a strong language mindset, positive L2 self, and intercultural communicative skills. The current study also demonstrated that language mindset and intercultural communicative skills were significant, positive predictors of positive L2 self and self-sustained English learning. Positive L2 self also significantly predicted self-sustained English learning. Additionally, language mindset and intercultural communicative skills had significant indirect effects on self-sustained English learning through the effect of positive L2 self. These findings have significant implications on how to nurture students’ self-sustained English learning and provide insights for understanding language beliefs, positive attitudes, intercultural competence, and their relationships with SSL among students who learn English as a second language. This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Luxi Yang, Hui Wang and Haiying Long; Data curation, Luxi Yang and Hao Zhang; Formal analysis, Haiying Long; Methodology, Hui Wang and Haiying Long; Project administration, Luxi Yang and Hao Zhang; Writing – original draft, Luxi Yang, Hui Wang and Haiying Long; Writing – review & editing, Hui Wang and Haiying Long.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Research Board at Chongqing Normal University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results.

References

- UNESCO. Education for sustainability: from Rio to Johannesburg, lessons learnt from a decade of commitment. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000127100.

- Rowe, D. Education for a sustainable future. Science 2007, 317((5836)), 323–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterling, S. Sustainable education – Re-visioning learning and change, Schumacher Briefing no 6. Schumacher Society/Green Books 2001, Dartington. Retrieved from https://www.greenbooks.co.uk/sustainable-education.

- Sterling, S. Sustainable Education. In Science, Society and Sustainability: Education and Empowerment for an Uncertain World; Gray, D., Colucci-Gray, L., Camino, E., Eds.; Routledge 2009.

- Ben-Eliyahu, A. Sustainable learning in education. Sustainability 2021, 13((8)), 4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, B. Interest and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective. Hum Dev 2006, 49((4)), 193–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, B.; Martin, C. K.; Roberts, E. Sparking self-sustained learning: Report on a design experiment to build technological fluency and bridge divides. Int J Technol Des Educ 2007, 17, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checketts, H. B. Guiding language students to self-sustained learning. Unpublished Thesis 2019. Utah State University.

- Yang, M. Promoting self-sustained learning in higher education: The ISEE framework. TEACH HIGH EDUC Journal 2015, 20((6)), 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J. Lifelong learning and the new educational order 2000. Trentham Books, Ltd.

- Zimmerman, B. J.; Schunk, D. H. Self-regulated learning and performance: An introduction and an overview. In Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance, 2011, pp. 15-26.

- Liu, M. Chinese students’ motivation to learn English at the tertiary level. Asian EFL Journal 2007, 9((1)), 126–146. [Google Scholar]

- Su, D. A study of English learning strategies and styles of Chinese university students in relation to their cultural beliefs and beliefs about learning English 1995. University of Georgia.

- Wang, C.; Hu, J.; Zhang, G.; Chang, Y.; & Xu, Y. Chinese college students’ self regulated learning strategies and self-efficacy beliefs in learning English as a foreign language. J. Educ. Res. 2012, 22(2), 103-135.

- Pan, H.; Liu, C.; Fang, F.; Elyas, T. “How is my English?”: Chinese university students’ attitudes toward China English and their identity construction. Sage Open 2021, 11(3), 21582440211038271.

- Ghasemi, A. A.; Ahmadian, M.; Yazdani, H.; & Amerian, M. Towards a model of intercultural communicative competence in Iranian EFL context: Testing the role of international posture, ideal L2 self, L2 self-confidence, and metacognitive strategies. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 2020, 49((1)), 41–60.

- Kanat-Mutluoğlu, A. The influence of ideal L2 self, academic self-concept and intercultural communicative competence on willingness to communicate in a foreign language. Eurasian J. Appl. Linguist 2016, 2((2)), 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, J.; Sawyer, M.; Beglar, D.; Swenson, T.; Kozaki, Y.; Elwood, J. A. Positive psychology and second language motivation: Empirically validating a model of positive L2 self 2015. Temple University Libraries.

- Lou, N. M.; Noels, K. A. Changing language mindsets: Implications for goal orientations and responses to failure in and outside the second language classroom. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 46, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, N. M.; Noels, K. A. Measuring Language Mindsets and Modeling Their Relations with Goal Orientations and Emotional and Behavioral Responses in Failure Situations. Mod. Lang. J. 2017, 101((1)), 214–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, N. M.; Noels, K. A. Breaking the vicious cycle of language anxiety: Growth language mindsets improve lower-competence ESL students’ intercultural interactions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design 1979. Harvard University Press.

- Rogoff, B. The cultural nature of human development 2003.Oxford University Press.

- Beach, K. D. Consequential transitions: A sociocultural expedition beyond transfer in education. Rev. Educ. Res. 1999, 24, 124–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidi, S. E.; Renninger, K. A. On educating, curiosity, and interest development. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2020, 35, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biwer, F.; oude Egbrink, M.G.; Aalten, P.; de Bruin, A.B. Fostering effective learning strategies in higher education–a mixed-methods study. J APPL RES MEM COGN. 2020, 9((2)), 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, R. A.; Hamm, J. M.; Parker, P. C. Promoting effective teaching and learning in higher education. Higher education: Handbook of theory and research 2015 Vol(30), 245-274.

- Hativa, N. Teaching for effective learning in higher education 2001. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Kinchin, I.M.; S. Lygo-Baker; D.B. Hay. Universities as centres of non-learning. High. Educ. Stud. 2008, 33(1), 89-103.

- Boud, D. Reframing assessment as if learning is important. In Rethinking assessment in higher education 2007, Routledge.

- Deardorff, D. K. Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. J Stud Int Educ 2006, 10((3)), 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwe, K, T.; Haskollar, E. Variables impacting intercultural competence: a systematic literature review. J Intercult Commun Res 2020, 49(4), 346-371. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M. J.; Bennett, J. M. Developing intercultural sensitivity: An integrative approach to global and domestic diversity. In D. Landis, J. M. Bennett, & M. J. Bennett (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training, 3rd ed., 2004, pp. 147-165. Sage.

- Li, F.; Liu, Y. The impact of a cultural research course project on foreign language students’ intercultural competence and language learning. J Lang Teach Res 2017, 8((1)), 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Róg, T.; Moros-Pałys, Z.; Wróbel, A.; Książek-Róg, M. Intercultural competence and L2 acquisition in the study abroad context. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 2020, 20(1), 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwari, A. Q.; Wahab, M. N. A. Relationship between English language proficiency and intercultural communication competence among international students in a Malaysian public university. Int. J. Lang. Edu. App. Ling. 2016, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T. J.; Sercombe, P. G.; Sachdev, I.; Naeb, R.; Schartner, A. Success factors for international postgraduate students’ adjustment: exploring the roles of intercultural competence, language proficiency, social contact and social support. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2013, 3((2)), 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, J.; Pawlak, M.; Mehraein, S.; Hosseini, H. M.; Derakhshesh, A. Foreign language enjoyment, ideal L2 self, and intercultural communicative competence as predictors of willingness to communicate among EFL learners. System 2023, 115, 103067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghetti, C. Integrating intercultural and communicative objectives in the foreign language class: A proposal for the integration of two models. Lang. Learn. J. 2013, 41((3)), 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, M. Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence 1997. Multilingual Matters.

- Hymes, D. On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride, & J. Holmes, Eds. 1972, Sociolinguistics, pp. 169–193. Penguin.

- Gao, Y. H. The ‘Dao’ and ‘Qi’ concept of intercultural competence. Lang. Teach. Res. 199, 3, 39–53.

- Jia, Y. X. Intercultural communication 1997. Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

- Yang, Y.; Zhuang, E. P. Framework for building cross-cultural communicative competence. Foreign Lang. Wor. 2007, 4, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, A. G.; Jiang, Y. M. Introduction to applied language and cultural studies 2003. Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

- Wu, W. P.; Fan, W. W.; & Peng, R. Z. An analysis of the assessment tools for Chinese college students’ intercultural competence. Foreign Lang. Teach. Res. 2013, 4, 581–592.

- Gu, X. Assessment of intercultural communicative competence in FL education: A survey on EFL teachers’ perception and practice in China. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 2016, 16(2), 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Constructing intercultural communicative competence framework for English learners. Cross-Cultural Comm. 2014, 10(1), 97-101.

- Ahnagari, S.; Zamanian, J. Intercultural communicative competence in foreign language classroom. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus Soc.Sci. 2014, 4((11)), 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byram, M. Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence 1997. Multilingual Matters Ltd.

- Fantini, A.E. Reconceptualizing intercultural communicative competence: A multinational perspective. Res. in Comp. and Int. Educ. 2020, 15((1)), 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Forouzandeh, F. Relationship between intercultural communicative competence and L2-learning motivation of Iranian EFL learners. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 2013, 42((3)), 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.Q.; Duong, T. M. The effectiveness of the intercultural language communicative teaching model for EFL learners. ASIAN-PAC J SEC FOR. 218, 3, 1-17.

- Apple, M. T.; Aliponga, J. Intercultural communication competence and possible L2 selves in a short-term study abroad program. New perspectives on the development of communicative and related competence in foreign language education 2018, 289-308. [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S. Mindset: The new psychology of success 2006. Random House.

- Lee, M.; Bong, M. Relevance of goal theories to language learning research. System 2019, 86, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J. L.; Pollack, J. M.; Forsyth, R. B.; Hoyt, C. L.; Babij, A. D.; Thomas, F. N.; Coy, A. E. A growth mindset intervention: Enhancing students’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy and career development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2020, 44((5)), 878–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S.; Yeager, D. S. Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 14((3)), 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyder, A.; Weidinger, A. F.; Steinmayr, R. Only a burden for females in math? Gender and domain differences in the relation between adolescents’ fixed mindsets and motivation. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterman, C. J.; Ewing, J. Effects of movement, growth mindset and math talks on math anxiety. J. Multi. Aff. 2019, 4((1)), 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrinabadi, N.; Rezazadeh, M.; Karimi, M.; Lou, N. M. Why do growth mindsets make you feel better about learning and yourselves? Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2022, 16((3)), 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E. The relationship of self-concepts to changes in cultural diversity awareness: Implications for urban teacher educators. Urban Rev. 2004, 36((2)), 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, F.; Leite, A. Adolescents’ self-concept short scale: A version of PHCSCS. Procedia Soc. 2016, 217, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W.; Craven, R. G. Reciprocal Effects of Self-Concept and Performance From a Multidimensional Perspective: Beyond Seductive Pleasure and Unidimensional Perspectives. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 1((2)), 133–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hoorie, A. H. The L2 motivational self system: A meta-analysis. Stu. in Sec. Lang. Learn. and Teach. 2018, 8((4)), 721–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Iqbal, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Xie, Y. Impact of self-concept, self-imagination, and self-efficacy on English language learning outcomes among blended learning students during COVID-19. Front. psychol. 2022, 13, 784444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskovsky, C.; Assulaimani, T.; Racheva, S.; & Harkins, J. The L2 Motivational Self System and L2 Achievement: A Study of Saudi EFL Learners. Mod. Lang. J. 2016, 100((3)), 641–654. [CrossRef]

- Trautwein, U.; Möller, J. Self-Concept: Determinants and consequences of academic Self-Concept in school contexts. In Plenum series on human exceptionality 2016, pp. 187–214. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. The roles of classroom social climate, language mindset, and positive L2 self in predicting Chinese college students’ academic resilience in English as a foreign language 2023. Unpublished Dissertation. University of Kansas.

- Wang, H.; Peng, A.; Patterson, M. M. The roles of class social climate, language mindset, and emotions in predicting willingness to communicate in a foreign language. System 2021, 99, 102529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, A.; Rakıcıoğlu-Söylemez, A. Language mindsets, perceived instrumentality, engagement and graded performance in English as a foreign language students. Lang. Teach. Res. 2020, 1362168820958400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavy, G. H.; MacIntyre, P. D.; Hariri, J. A closer look at grit and language mindset as predictors of foreign language achievement. Stu. Sec. Lang. Acq. 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R. Z.; Wu, W. P. Measuring intercultural contact and its effects on intercultural competence: A structural equation modeling approach. Int. J. Intercul. Rel. 2016, 53, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R. Z.; Wu, W. P.; Fan, W.W. A comprehensive evaluation of Chinese college students’ intercultural competence. Int. J. Intercul. Rel. 2015, 47, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R. Z.; Zhu, C.; Wu, W. P. Visualizing the knowledge domain of intercultural competence research: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Intercul. Rel. 2020, 74, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucker, D. D.; Preacher, K. J.; Tormala, Z. L.; Petty, R. E. Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Soc. Personal. Psychol. 2011, 5(6), 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W.; Lau, R. S. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation modeling. Organ. Res. Methods, 2007, 11(2), 296–325. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C.; Gerbing, D. W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103(3), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling 2023. Guilford Publications.

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. Mplus user’s guide (1998–2012) 2012. Muthén & Muthén.

- Bandalos, D. L. The effects of item parceling on goodness-of-fit and parameter estimate bias in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2002, 9((1)), 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T. D.; Cunningham, W.A.; Shahar, G.; Widaman, K. F. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2002, 9((2)), 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W.; Hau, K. T.; Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2004, 11((3)), 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J. B.; Nora, A.; Stage, F. K.; Barlow, E. A.; King, J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99((6)), 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M. J.; Gonzalez, O.; Miocevic, M.; & MacKinnon, D. P. A note on testing mediated effects in Structural Equation Models: Reconciling past and current research on the performance of the test of joint significance. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2016, 76((6)), 889–911. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X. The role of effort in understanding academic achievements: empirical evidence from China. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 39((1)), 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Participant Demographics.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics.

| Variables |

Categories |

N |

% |

| Gender |

Female |

850 |

68.7 |

| Male |

388 |

31.3 |

| Grade |

Undergraduate |

808 |

65.3 |

| |

Graduate |

430 |

34.7 |

| Major |

English Major |

940 |

75.9 |

| |

Non-English Major |

298 |

24.1 |

| Length of English Learning |

Less than 5 years |

89 |

7.2 |

| 5-10 Years |

757 |

61.1 |

| 11-15 Year |

314 |

25.4 |

| More than 15 Years |

78 |

6.3 |

| Self-Rated English Proficiency Level |

Very Poor |

43 |

3.5 |

| Poor |

211 |

17.0 |

| Fair |

815 |

65.8 |

| Good |

37 |

3.0 |

| Very Good |

|

|

| Going Abroad |

No |

1,149 |

92.8 |

| |

Yes |

89 |

7.2 |

| Contact with Native Speakers |

No |

704 |

56.9 |

| Once or more per year |

286 |

23.1 |

| Once or more per month |

66 |

5.3 |

| Once or more per week |

149 |

12.0 |

| Once or more per day |

33 |

2.7 |

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of All Variables.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of All Variables.

| Variables |

Mean |

SD |

| LM Parcel 1-Second Language Beliefs |

3.75 |

0.79 |

| LM Parcel 2-Age Sensitivity Beliefs |

3.88 |

0.85 |

| LM Parcel 3-General Language Beliefs |

3.69 |

0.83 |

| PLS Parcel 1-Interest |

3.71 |

0.83 |

| PLS Parcel 2-Harmonious Passion |

3.66 |

0.83 |

| PLS Parcel 3-Mastery L2 Goal |

3.72 |

0.79 |

| SSL-Short-Term |

3.07 |

0.95 |

| SSL-Long-Term |

3.63 |

0.99 |

| ICS 1 |

3.21 |

1.00 |

| ICS2 |

3.55 |

0.88 |

| ICS3 |

3.23 |

0.98 |

| ICS4 |

3.79 |

0.91 |

| ICS5 |

3.71 |

0.90 |

| ICS6 |

3.71 |

0.89 |

| ICS7 |

3.72 |

0.89 |

| ICS8 |

3.48 |

0.90 |

| ICS9 |

3.56 |

0.88 |

Table 3.

Correlations of Latent Variables.

Table 3.

Correlations of Latent Variables.

| Variables |

LM |

ICS |

PLS |

SSL |

| LM |

- |

|

|

|

| ICS |

.34** |

- |

- |

|

| PLS |

.44** |

.40** |

- |

- |

| SSL |

.43** |

.39** |

.50** |

- |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).