Submitted:

18 June 2024

Posted:

20 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Importance of Healthy Skin and Hair in Society

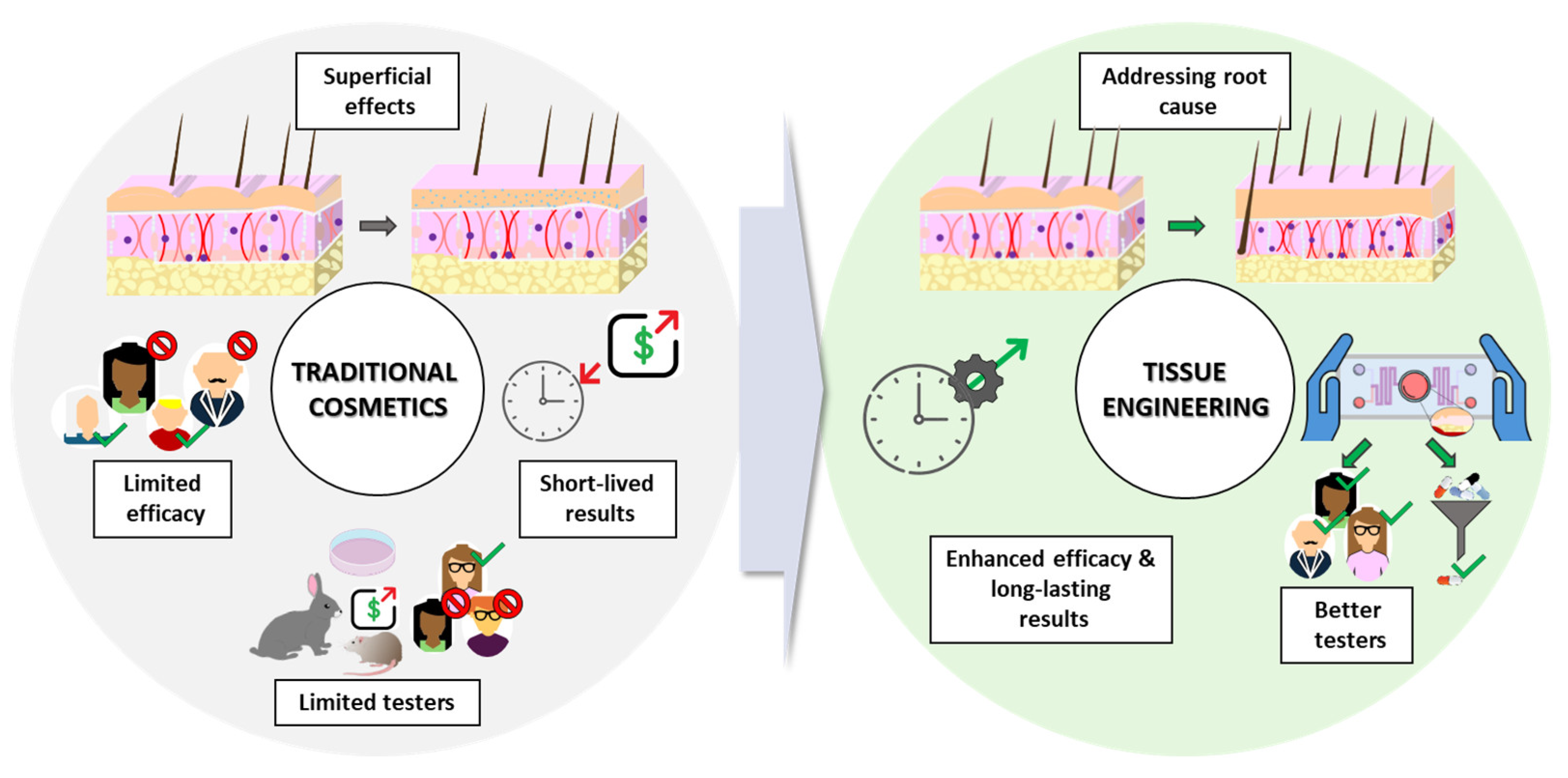

1.2. Limitations of Traditional Cosmetic Approaches

1.3. The Promise of TE-Based Dermocosmetics

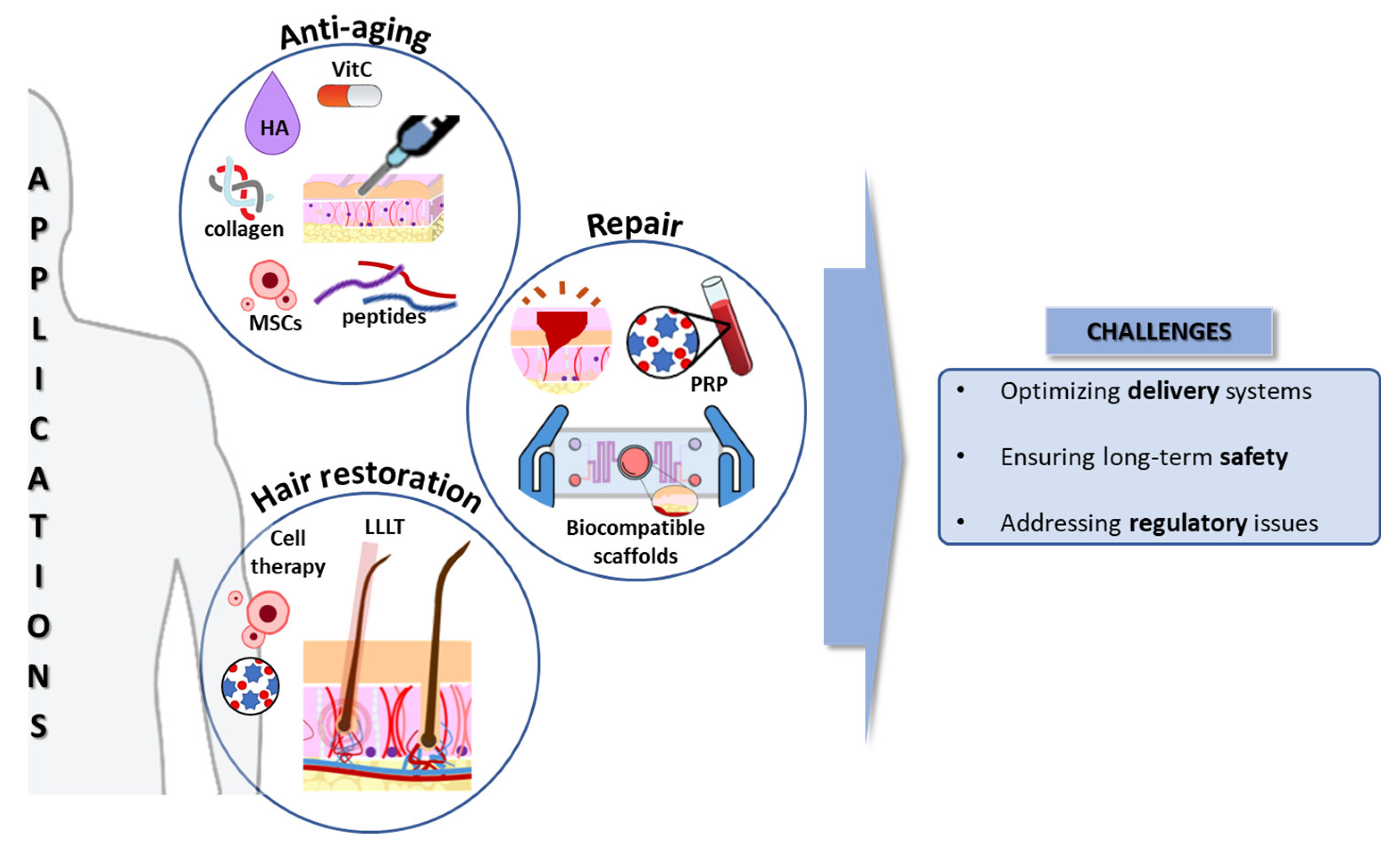

- Cells: these can include adult stem cells (mesenchymal stem/stromal cells, MSCs; or adipose-derived stem cells, ADSCs), or even differentiated skin cells (fibroblasts, keratinocytes).

- Scaffolds: these provide a 3D structure that supports cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation.

- Signals: bioactive molecules, growth factors (epidermal growth factor, EGF; fibroblast growth factor, FGF; platelet-derived growth factor, PDGF), vitamins, antioxidants, and even mechanical or electrical stimulation, can be used to modify cellular behavior.

- Addressing the root cause: TE-based dermocosmetics aim to address the underlying biological processes responsible for various skin and hair concerns. This can involve stimulating collagen production for anti-aging effects, promoting wound healing through the delivery of growth factors, or even facilitating hair follicle (HF) regeneration through the use of bioengineered scaffolds [15].

- Enhanced efficacy: by targeting specifically the dermal compartment, dermocosmetics derived from TE, including new delivery methods, improve the efficacy of the bioactive compounds or key proteins such as collagen. This can significantly improve areas like scar regeneration and wound healing [16,17].

- Long-lasting results: some TE techniques, like the application of stem cells or their exosomes, show promise for promoting long-lasting results by stimulating cell proliferation and collagen production. This can significantly reduce the need for frequent product application and improve patient compliance [18,19].

- Better testers: ex-vivo skin models, such as 3D “skin-on-a-chip” (SoC) systems combined with microfluidics, offer a promising alternative to traditional testing methods. These models provide a more realistic recreation of human skin architecture and function, enabling more accurate dermocosmetic product testing [20,21].

2. Mechanisms Involved in Regenerative Cosmetics

2.1. Skin Aging

- Stimulating collagen production: growth factors, vitamins, and peptides can signal skin cells to increase collagen production, leading to wrinkle reduction and improved skin firmness. However, this has to be performed in the dermal compartment, so the topic application, unless the molecules can go through the epithelial barrier, presents a limited efficacy [23,24].

- Wrinkle reduction: biocompatible fillers like hyaluronic acid (HA) can be injected to plump up the skin and reduce wrinkles [25]. Microneedling introduces the bioactive compounds into the right dermal layer and creates controlled micro-injuries, stimulating collagen production and reducing wrinkle depth [26]. Additionally, exosome-based cosmetics are emerging as a novel approach for wrinkle reduction. Studies suggest that exosomes derived from MSCs, with their paracrine effects, may promote collagen synthesis and improve skin elasticity [27].

- Improving skin restoration: engineered skin substitutes can address specific concerns like chronic wounds, infections, or pigmentation disorders by enhancing barrier function, hydration, immune response against pathogens, and wound healing [28].

2.2. Oxidative Stress

2.3. Repair versus Regeneration

- Promoting wound healing: engineered skin substitutes like biocompatible scaffolds provide a structure for cell migration and tissue regeneration, accelerating wound healing and minimizing scar formation [50]. Current skin substitutes have been tested for addressing regeneration in burn patients, chronic ulcers (diabetes), and rare genodermatoses (Epidermolysis bullosa) [51]. Novel technologies, including injectable cell suspensions and 3D scaffolds, are promising for improving wound healing and skin regeneration [52].

- Scar reduction: microneedling and fractional laser therapy, combined with regenerative ingredients like growth factors, can stimulate collagen production and improve the appearance of existing scars [53,54]. Additionally, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy is gaining traction as a potential scar reduction technique. Studies suggest that PRP injections may improve scar quality and reduce scar tissue formation [55], which is particularly interesting in relation to acne scars.

2.4. Fibrosis and Connective Tissue in Skin Rejuvenation

- Modulate the fibrotic process: by understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying fibrosis, researchers can develop strategies to control collagen deposition and promote scarless wound healing, and also highlight the role of macrophages in the inflammatory phase [56].

- Enhance the functionality of the connective tissue: supporting the health and organization of the connective tissue, which provides structural support and elasticity to the skin, is crucial for maintaining a youthful appearance and function, and this is particularly interesting when the role of MSCs is studied in UV-associated skin aging [58].

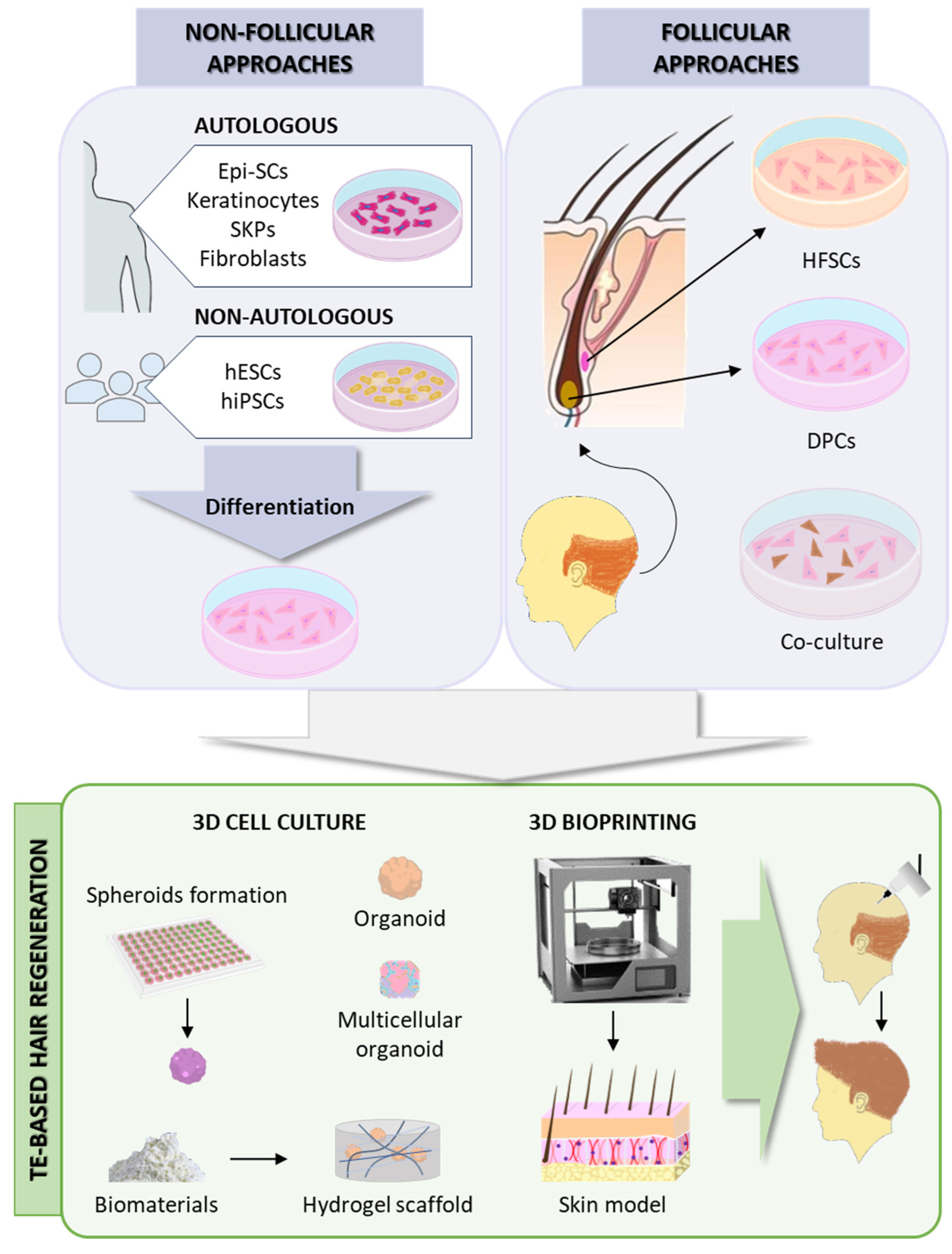

2.5. Hair Follicle Regeneration

3. Regenerative Cosmetics: A Transformative Alternative

3.1. OMIC Approaches: A Key Tool for Regenerative Cosmetics

3.1.1. Proteomics

3.1.2. Metabolomics

3.1.3. Multi-OMICs Integration

3.2. Skin Modelling Accelerates Drug Development

- Materials: 3D SoC models use polymers like polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), polycaprolactone (PCL), and polylactic acid (PLA) for their cost-effectiveness and biocompatibility. Hydrogels such as alginate and collagen mimic human tissue but lack mechanical precision. Animal-derived materials offer realism but raise cost and ethical issues. Innovations like decellularized ECM and silk improve cell environments [92,95,96,97,98,99].

- Challenges: SoC models face challenges in controlling chemical gradients, technical sampling, and analysis. Integrating vasculature and microbiomes is crucial for physiological accuracy. Despite these, models like EpiDerm from MatTek Corporation or SkinEthic from L’Oréal, show promise for dermocosmetics, offering safety and efficacy benefits over traditional methods [90,100,101].

3.3. Potential Solutions for Hair Loss and Promotion of Thicker, Healthier Hair Growth

- Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) stimulates hair growth with minimal side effects by exposing tissues to low-level light energy, showing a synergistic effect on promoting hair regrowth [103].

- Autologous PRP treatment, derived from the patient’s blood, stimulates hair growth through the release of growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines, promoting cell proliferation, differentiation, and angiogenesis [110].

- Nanoparticles have been studied for drug delivery directly into the HF, minimizing the systemic adverse effects [103].

4. Revolutionizing Beauty: The Convergence of Regenerative Medicine and Cosmetic Science

5. Challenges and Future Opportunities in this Field

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouwstra, J.A.; Nadaban, A.; Bras, W.; McCabe, C.; Bunge, A.; Gooris, G.S. The skin barrier: An extraordinary interface with an exceptional lipid organization. Prog Lipid Res 2023, 92, 101252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansbridge, J. Skin tissue engineering. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2008, 19, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasisi, T.; Smallcombe, J.W.; Kenney, W.L.; Shriver, M.D.; Zydney, B.; Jablonski, N.G.; Havenith, G. Human scalp hair as a thermoregulatory adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2301760120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverberg, J.I. Comorbidities and the impact of atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2019, 123, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H.W.; Ryou, S.; Jeong, J.H.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, K.J.; Lee, S.B.; Shin, H.T.; Byun, J.W.; Shin, J.; Choi, G.S. The Quality of Life and Psychosocial Impact on Female Pattern Hair Loss. Ann Dermatol 2024, 36, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahluwalia, J.; Fabi, S.G. The psychological and aesthetic impact of age-related hair changes in females. J Cosmet Dermatol 2019, 18, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schielein, M.C.; Tizek, L.; Ziehfreund, S.; Sommer, R.; Biedermann, T.; Zink, A. Stigmatization caused by hair loss - a systematic literature review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2020, 18, 1357–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandy, P.; Shrivastava, T. Exploring the Multifaceted Impact of Acne on Quality of Life and Well-Being. Cureus 2024, 16, e52727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoli, M.J.; Sadoughifar, R.; Schwartz, R.A.; Lotti, T.M.; Janniger, C.K. Female pattern hair loss: A comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther 2020, 33, e14055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, K.; Meah, N.; Bhoyrul, B.; Sinclair, R. A review of the treatment of male pattern hair loss. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2020, 21, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhapte-Pawar, V.; Kadam, S.; Saptarsi, S.; Kenjale, P.P. Nanocosmeceuticals: facets and aspects. Future Sci OA 2020, 6, FSO613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyas, K.S.; Kaufman, J.; Munavalli, G.S.; Robertson, K.; Behfar, A.; Wyles, S.P. Exosomes: the latest in regenerative aesthetics. Regen Med 2023, 18, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathes, S.H.; Ruffner, H.; Graf-Hausner, U. The use of skin models in drug development. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2014, 69-70, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkiri, M.; Fox, S.C.; Fratila-Apachitei, L.E.; Zadpoor, A.A. Bioengineered Skin Intended for Skin Disease Modeling. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matama, T.; Costa, C.; Fernandes, B.; Araujo, R.; Cruz, C.F.; Tortosa, F.; Sheeba, C.J.; Becker, J.D.; Gomes, A.; Cavaco-Paulo, A. Changing human hair fibre colour and shape from the follicle. J Adv Res 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monavarian, M.; Kader, S.; Moeinzadeh, S.; Jabbari, E. Regenerative Scar-Free Skin Wound Healing. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2019, 25, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourian Dehkordi, A.; Mirahmadi Babaheydari, F.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Raeisi Dehkordi, S. Skin tissue engineering: wound healing based on stem-cell-based therapeutic strategies. Stem Cell Res Ther 2019, 10, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, H.; Brito, S.; Kwak, B.M.; Park, S.; Lee, M.G.; Bin, B.H. Applications of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Skin Regeneration and Rejuvenation. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, B.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Li, T.; Gong, J.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Q. Stem cell-derived exosomes: emerging therapeutic opportunities for wound healing. Stem Cell Res Ther 2023, 14, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlin, S.; Silva, M.S.D.; Facchini, G.; Silva, G.H.D.; Pinheiro, A.; Eberlin, S.; Pinheiro, A.D.S. The Ex Vivo Skin Model as an Alternative Tool for the Efficacy and Safety Evaluation of Topical Products. Altern Lab Anim 2020, 48, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataillon, M.; Lelievre, D.; Chapuis, A.; Thillou, F.; Autourde, J.B.; Durand, S.; Boyera, N.; Rigaudeau, A.S.; Besne, I.; Pellevoisin, C. Characterization of a New Reconstructed Full Thickness Skin Model, T-Skin, and its Application for Investigations of Anti-Aging Compounds. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Rho, N.K.; Park, K.Y. Skin aging from mechanisms to interventions: focusing on dermal aging. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1195272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gref, R.; Delomenie, C.; Maksimenko, A.; Gouadon, E.; Percoco, G.; Lati, E.; Desmaele, D.; Zouhiri, F.; Couvreur, P. Vitamin C-squalene bioconjugate promotes epidermal thickening and collagen production in human skin. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 16883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skibska, A.; Perlikowska, R. Signal Peptides - Promising Ingredients in Cosmetics. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2021, 22, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari, S.N.A.; Roswandi, N.L.; Waqas, M.; Habib, H.; Hussain, F.; Khan, S.; Sohail, M.; Ramli, N.A.; Thu, H.E.; Hussain, Z. Hyaluronic acid, a promising skin rejuvenating biomedicine: A review of recent updates and pre-clinical and clinical investigations on cosmetic and nutricosmetic effects. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 120, 1682–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spataro, E.A.; Dierks, K.; Carniol, P.J. Microneedling-Associated Procedures to Enhance Facial Rejuvenation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2022, 30, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Yoo, S.M.; Park, H.H.; Lim, H.J.; Kim, Y.L.; Lee, S.; Seo, K.W.; Kang, K.S. Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells stimulates rejuvenation of human skin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017, 493, 1102–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Sanchez, A.; Kim, K.H.; Blasco-Morente, G.; Arias-Santiago, S. Cellular human tissue-engineered skin substitutes investigated for deep and difficult to heal injuries. NPJ Regen Med 2021, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, J.; Lee, M.G. Oxidative stress and antioxidant strategies in dermatology. Redox Rep 2016, 21, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouba, K.J.; Hamadeh, H.K.; Amin, R.P.; Germolec, D.R. Oxidative stress and its role in skin disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2002, 4, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, G.L.; Mitran, C.I.; Mitran, M.I.; Tampa, M.; Matei, C.; Popa, M.I.; Georgescu, S.R. Markers of Oxidative Stress in Patients with Acne: A Literature Review. Life (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.A. Rosacea, reactive oxygen species, and azelaic Acid. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2009, 2, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, H.; Mirnezami, M.; Yazdabadi, A.; Hajihashemi, A. Evaluation of systemic oxidative stress in patients with melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol 2024, 23, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prie, B.E.; Voiculescu, V.M.; Ionescu-Bozdog, O.B.; Petrutescu, B.; Iosif, L.; Gaman, L.E.; Clatici, V.G.; Stoian, I.; Giurcaneanu, C. Oxidative stress and alopecia areata. J Med Life 2015, 8 Spec Issue, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zapatero-Solana, E.; Garcia-Gimenez, J.L.; Guerrero-Aspizua, S.; Garcia, M.; Toll, A.; Baselga, E.; Duran-Moreno, M.; Markovic, J.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M.; Conti, C.J.; et al. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Kindler syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padayatty, S.J.; Katz, A.; Wang, Y.; Eck, P.; Kwon, O.; Lee, J.H.; Chen, S.; Corpe, C.; Dutta, A.; Dutta, S.K.; et al. Vitamin C as an antioxidant: evaluation of its role in disease prevention. J Am Coll Nutr 2003, 22, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niki, E. Interaction of ascorbate and alpha-tocopherol. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1987, 498, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farris, P.K. Topical vitamin C: a useful agent for treating photoaging and other dermatologic conditions. Dermatol Surg 2005, 31, 814–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turcov, D.; Zbranca-Toporas, A.; Suteu, D. Bioactive Compounds for Combating Oxidative Stress in Dermatology. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, S.; El-Husseny, M.W.A.; Abushouk, A.I.; Salem, A.M.A.; Mamdouh, M.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Effects of Antioxidant Supplements on the Survival and Differentiation of Stem Cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 5032102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Kawakatsu, M.; Guo, C.W.; Urata, Y.; Huang, W.J.; Ali, H.; Doi, H.; Kitajima, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Goto, S.; et al. Effects of antioxidants on the quality and genomic stability of induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.M.; Seo, Y.K.; Yoon, H.H.; Song, K.Y.; Kwon, S.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Park, J.K. Effect of ascorbic acid on bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and differentiation. J Biosci Bioeng 2008, 105, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, A.E.; Wong, Y.T.; Ho, R.; Wasser, M.; Du, T.; Ng, W.T.; Halliwell, B. Effects of hydrogen peroxide on wound healing in mice in relation to oxidative damage. PLoS One 2012, 7, e49215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyublinskaya, O.G.; Borisov, Y.G.; Pugovkina, N.A.; Smirnova, I.S.; Obidina, J.V.; Ivanova, J.S.; Zenin, V.V.; Shatrova, A.N.; Borodkina, A.V.; Aksenov, N.D.; et al. Reactive Oxygen Species Are Required for Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells to Initiate Proliferation after the Quiescence Exit. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015, 2015, 502105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Deken, X.; Corvilain, B.; Dumont, J.E.; Miot, F. Roles of DUOX-mediated hydrogen peroxide in metabolism, host defense, and signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014, 20, 2776–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Du, J.; Yuan, D.F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.C.; Mi, J.W.; Ning, Y.L.; Chen, M.J.; Wen, D.L.; et al. Optimal H(2)O(2) preconditioning to improve bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells’ engraftment in wound healing. Stem Cell Res Ther 2020, 11, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buron, M.; Palomares, T.; Garrido-Pascual, P.; Herrero de la Parte, B.; Garcia-Alonso, I.; Alonso-Varona, A. Conditioned Medium from H(2)O(2)-Preconditioned Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Ameliorates UVB-Induced Damage to Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Son, J.Y.; Kang, J.I.; Park, K.M.; Park, K.D. Hydrogen Peroxide-Releasing Hydrogels for Enhanced Endothelial Cell Activities and Neovascularization. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10, 18372–18379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleguezuelos-Beltran, P.; Galvez-Martin, P.; Nieto-Garcia, D.; Marchal, J.A.; Lopez-Ruiz, E. Advances in spray products for skin regeneration. Bioact Mater 2022, 16, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Santamaria, L.; Guerrero-Aspizua, S.; Del Rio, M. Skin bioengineering: preclinical and clinical applications. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2012, 103, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chocarro-Wrona, C.; Lopez-Ruiz, E.; Peran, M.; Galvez-Martin, P.; Marchal, J.A. Therapeutic strategies for skin regeneration based on biomedical substitutes. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019, 33, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disphanurat, W.; Sivapornpan, N.; Srisantithum, B.; Leelawattanachai, J. Efficacy of a triamcinolone acetonide-loaded dissolving microneedle patch for the treatment of hypertrophic scars and keloids: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled split-scar study. Arch Dermatol Res 2023, 315, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waghmare, K.B.; Sequeira, J.; Rao, B.H.S. An objective assessment of microneedling therapy in atrophic facial acne scars. Natl J Maxillofac Surg 2022, 13, S103–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, T.; Gupta, A.; Ma, S.; Hsu, S. Platelet-rich plasma in noninvasive procedures for atrophic acne scars: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cosmet Dermatol 2020, 19, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mony, M.P.; Harmon, K.A.; Hess, R.; Dorafshar, A.H.; Shafikhani, S.H. An Updated Review of Hypertrophic Scarring. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tartaglia, G.; Cao, Q.; Padron, Z.M.; South, A.P. Impaired Wound Healing, Fibrosis, and Cancer: The Paradigm of Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Jin, S.; Wang, P.; He, Q.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Wang, X. Microneedle based adipose derived stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles therapy ameliorates UV-induced photoaging in SKH-1 mice. J Biomed Mater Res A 2021, 109, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorg, H.; Tilkorn, D.J.; Hager, S.; Hauser, J.; Mirastschijski, U. Skin Wound Healing: An Update on the Current Knowledge and Concepts. Eur Surg Res 2017, 58, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhu, L.; He, J. Morphogenesis, Growth Cycle and Molecular Regulation of Hair Follicles. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 899095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandishi, A.K.; Esmaeili, A.; Taghipour, N. The promising prospect of human hair follicle regeneration in the shadow of new tissue engineering strategies. Tissue Cell 2024, 87, 102338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llamas-Molina, J.M.; Carrero-Castano, A.; Ruiz-Villaverde, R.; Campos, A. Tissue Engineering and Regeneration of the Human Hair Follicle in Androgenetic Alopecia: Literature Review. Life (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, A.R.; Logarinho, E. Tissue engineering strategies for human hair follicle regeneration: How far from a hairy goal? Stem Cells Transl Med 2020, 9, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Yu, E.; Wu, M.; Wei, P.; Yin, J. Cells, growth factors and biomaterials used in tissue engineering for hair follicles regeneration. Regen Ther 2022, 21, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kageyama, T.; Yan, L.; Shimizu, A.; Maruo, S.; Fukuda, J. Preparation of hair beads and hair follicle germs for regenerative medicine. Biomaterials 2019, 212, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Miao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lin, B.; Liu, X.; Xiao, S.; Du, L.; Hu, Z.; Xing, M. Bottom-up Nanoencapsulation from Single Cells to Tunable and Scalable Cellular Spheroids for Hair Follicle Regeneration. Adv Healthc Mater 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yin, P.; Huang, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z.; Fu, D.; Hu, Z.; Huang, W.; Miao, Y. Scalable and high-throughput production of an injectable platelet-rich plasma (PRP)/cell-laden microcarrier/hydrogel composite system for hair follicle tissue engineering. J Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, T.; Nanmo, A.; Yan, L.; Nittami, T.; Fukuda, J. Effects of platelet-rich plasma on in vitro hair follicle germ preparation for hair regenerative medicine. J Biosci Bioeng 2020, 130, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Bai, X.; Yuan, Z.; Cao, X.; Jiao, X.; Qin, Y.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, X. Cellular Nanofiber Structure with Secretory Activity-Promoting Characteristics for Multicellular Spheroid Formation and Hair Follicle Regeneration. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12, 7931–7941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Martos, S.; Calvo-Sanchez, M.; Garcia-Alonso, K.; Castro, B.; Hashtroody, B.; Espada, J. Sustained Human Hair Follicle Growth Ex Vivo in a Glycosaminoglycan Hydrogel Matrix. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Chen, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, C.; Li, H. Self-assembled complete hair follicle organoids by coculture of neonatal mouse epidermal cells and dermal cells in Matrigel. Ann Transl Med 2022, 10, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, S.; Liu, B.; Miao, Y.; Hu, Z. Use of extracellular matrix hydrogel from human placenta to restore hair-inductive potential of dermal papilla cells. Regen Med 2019, 14, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barat, T.; Abdollahimajd, F.; Dadkhahfar, S.; Moravvej, H. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of cow placenta extract lotion versus minoxidil 2% in the treatment of female pattern androgenetic alopecia. Int J Womens Dermatol 2020, 6, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motter Catarino, C.; Cigaran Schuck, D.; Dechiario, L.; Karande, P. Incorporation of hair follicles in 3D bioprinted models of human skin. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eadg0297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.; Liu, Z.; Qian, C.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Mao, X.; Qu, Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Hu, Z.; et al. 3D bioprinting of a gelatin-alginate hydrogel for tissue-engineered hair follicle regeneration. Acta Biomater 2023, 165, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.S.; Kwon, M.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, W.H.; Lee, G.W.; Jo, H.J.; Kim, B.; Yang, S.Y.; Kim, K.S.; Han, D.W. 3D Printing of Skin Equivalents with Hair Follicle Structures and Epidermal-Papillary-Dermal Layers Using Gelatin/Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogels. Chem Asian J 2022, 17, e202200620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.Y.; Hu, X.M.; Huang, K.; Li, Z.H.; Chen, Q.N.; Yang, R.H.; Xiong, K. Proteomics as a tool to improve novel insights into skin diseases: what we know and where we should be going. Front Surg 2022, 9, 1025557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, I.; Burty-Valin, E.; Radman, M. A Proteome-Centric View of Ageing, including that of the Skin and Age-Related Diseases: Considerations of a Common Cause and Common Preventative and Curative Interventions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2023, 16, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pien, N.; Bray, F.; Gheysens, T.; Tytgat, L.; Rolando, C.; Mantovani, D.; Dubruel, P.; Vlierberghe, S.V. Proteomics as a tool to gain next level insights into photo-crosslinkable biopolymer modifications. Bioact Mater 2022, 17, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.X.; Chang, T.; Lin, X. Secretomes as an emerging class of bioactive ingredients for enhanced cosmeceutical applications. Exp Dermatol 2022, 31, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masutin, V.; Kersch, C.; Schmitz-Spanke, S. A systematic review: metabolomics-based identification of altered metabolites and pathways in the skin caused by internal and external factors. Exp Dermatol 2022, 31, 700–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knox, S.; O’Boyle, N.M. Skin lipids in health and disease: A review. Chem Phys Lipids 2021, 236, 105055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhu, Z.; Du, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wu, W.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Jiang, C.; et al. A Skin Lipidomics Study Reveals the Therapeutic Effects of Tanshinones in a Rat Model of Acne. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 675659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, Q.; Zhong, Q.; Duan, C.; Krutmann, J.; Wang, J.; Xia, J. Skin Microbiome, Metabolome and Skin Phenome, from the Perspectives of Skin as an Ecosystem. Phenomics 2022, 2, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gueniche, A.; Perin, O.; Bouslimani, A.; Landemaine, L.; Misra, N.; Cupferman, S.; Aguilar, L.; Clavaud, C.; Chopra, T.; Khodr, A. Advances in Microbiome-Derived Solutions and Methodologies Are Founding a New Era in Skin Health and Care. Pathogens 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, T.; Geng, R.; Kang, S.G.; Li, X.; Huang, K. Revitalizing Photoaging Skin through Eugenol in UVB-Exposed Hairless Mice: Mechanistic Insights from Integrated Multi-Omics. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafont, J.; Mencia, A.; Garcia, M.; Torres, R.; Rodriguez, S.; Carretero, M.; Chacon-Solano, E.; Modamio-Hoybjor, S.; Marinas, L.; Leon, C.; et al. Clinically Relevant Correction of Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa by Dual sgRNA CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Editing. Mol Ther 2019, 27, 986–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretero, M.; Guerrero-Aspizua, S.; Del Rio, M. Bioengineered skin humanized model of psoriasis. Methods Mol Biol 2013, 961, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Aspizua, S.; Carretero, M.; Conti, C.J.; Del Rio, M. The importance of immunity in the development of reliable animal models for psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Immunol Cell Biol 2020, 98, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Carro, E.; Angenent, M.; Gracia-Cazana, T.; Gilaberte, Y.; Alcaine, C.; Ciriza, J. Modeling an Optimal 3D Skin-on-Chip within Microfluidic Devices for Pharmacological Studies. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.O.; Sousa, P.C.; Gaspar, J.; Banobre-Lopez, M.; Lima, R.; Minas, G. Organ-on-a-Chip: A Preclinical Microfluidic Platform for the Progress of Nanomedicine. Small 2020, 16, e2003517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponmozhi, J.; Dhinakaran, S.; Varga-Medveczky, Z.; Fonagy, K.; Bors, L.A.; Ivan, K.; Erdo, F. Development of Skin-On-A-Chip Platforms for Different Utilizations: Factors to Be Considered. Micromachines (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadali, M.; Ghiaseddin, A.; Irani, S.; Amirkhani, M.A.; Dahmardehei, M. Design and evaluation of a skin-on-a-chip pumpless microfluidic device. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wufuer, M.; Lee, G.; Hur, W.; Jeon, B.; Kim, B.J.; Choi, T.H.; Lee, S. Skin-on-a-chip model simulating inflammation, edema and drug-based treatment. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 37471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, M.J.; Jungel, A.; Rimann, M.; Wuertz-Kozak, K. Advances in the Biofabrication of 3D Skin in vitro: Healthy and Pathological Models. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2018, 6, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellas, E.; Seiberg, M.; Garlick, J.; Kaplan, D.L. In vitro 3D full-thickness skin-equivalent tissue model using silk and collagen biomaterials. Macromol Biosci 2012, 12, 1627–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parenteau-Bareil, R.; Gauvin, R.; Cliche, S.; Gariepy, C.; Germain, L.; Berthod, F. Comparative study of bovine, porcine and avian collagens for the production of a tissue engineered dermis. Acta Biomater 2011, 7, 3757–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, E.; Diaferia, C.; Gianolio, E.; Sibillano, T.; Gallo, E.; Smaldone, G.; Stornaiuolo, M.; Giannini, C.; Morelli, G.; Accardo, A. Multicomponent Hydrogel Matrices of Fmoc-FF and Cationic Peptides for Application in Tissue Engineering. Macromol Biosci 2022, 22, e2200128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arab, W.T.; Susapto, H.H.; Alhattab, D.; Hauser, C.A.E. Peptide nanogels as a scaffold for fabricating dermal grafts and 3D vascularized skin models. J Tissue Eng 2022, 13, 20417314221111868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal-Ozturk, A.; Miccoli, B.; Avci-Adali, M.; Mogtader, F.; Sharifi, F.; Cecen, B.; Yasayan, G.; Braeken, D.; Alarcin, E. Current Strategies and Future Perspectives of Skin-on-a-Chip Platforms: Innovations, Technical Challenges and Commercial Outlook. Curr Pharm Des 2018, 24, 5437–5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurat, M.T.; Ergun, C.; Elcin, A.E.; Elcin, Y.M. 3D Bioprinting of Tissue Models with Customized Bioinks. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020, 1249, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez, F.; Alam, M.; Vogel, J.E.; Avram, M. Hair transplantation: Basic overview. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021, 85, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzer, T.; Leite Junior, A.; Beck, R.; da Silva, C. Physiopathology and current treatments of androgenetic alopecia: Going beyond androgens and anti-androgens. Dermatol Ther 2019, 32, e13059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Polla Ravi, S.; Wang, T.; Talukder, M.; Starace, M.; Piraccini, B.M. Scoping Reviewof mesotherapy: a novel avenue for the treatment of hair loss. J Dermatolog Treat 2023, 34, 2245084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Fan, Z.; Qu, Q.; Miao, Y. Current application of mesotherapy in pattern hair loss: A systematic review. J Cosmet Dermatol 2022, 21, 4184–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherani, N.; Smoller, B.R.; Tavoosidana, G.; Ghanadan, A.; Wollina, U.; Lotti, T. An overview of the role of carboxytherapy in dermatology. J Cosmet Dermatol 2023, 22, 2399–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroumpouzos, G.; Arora, G.; Kassir, M.; Galadari, H.; Wollina, U.; Lotti, T.; Grabbe, S.; Goldust, M. Carboxytherapy in dermatology. Clin Dermatol 2022, 40, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, R.S., Jr.; Ruiz, S.; DoAmaral, P. Microneedling and Its Use in Hair Loss Disorders: A Systematic Review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2022, 12, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocampo-Garza, S.S.; Fabbrocini, G.; Ocampo-Candiani, J.; Cinelli, E.; Villani, A. Micro needling: A novel therapeutic approach for androgenetic alopecia, A Review of Literature. Dermatol Ther 2020, 33, e14267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paichitrojjana, A.; Paichitrojjana, A. Platelet Rich Plasma and Its Use in Hair Regrowth: A Review. Drug Des Devel Ther 2022, 16, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, A.R.; Bian, Q.; Gao, J.Q. Current advances in stem cell-based therapies for hair regeneration. Eur J Pharmacol 2020, 881, 173197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, P.T. Advances in Hair Restoration. Dermatol Clin 2018, 36, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwack, M.H.; Seo, C.H.; Gangadaran, P.; Ahn, B.C.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, J.C.; Sung, Y.K. Exosomes derived from human dermal papilla cells promote hair growth in cultured human hair follicles and augment the hair-inductive capacity of cultured dermal papilla spheres. Exp Dermatol 2019, 28, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudian-Sani, M.R.; Jamshidi, M.; Asgharzade, S. Combined Growth Factor and Gene Therapy: An Approach for Hair Cell Regeneration and Hearing Recovery. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 2018, 80, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).