Submitted:

19 June 2024

Posted:

19 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Experimental Procedures

2.3. Ethical Statement

2.4. Personality Assay

2.4.1. Boldness

2.4.2. Exploration

2.5. Foraging Behavior

2.6. Morphology Traits

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.7.1. Personality

2.7.2. Foraging Behavior

2.7.3. Morphological Traits

3. Results

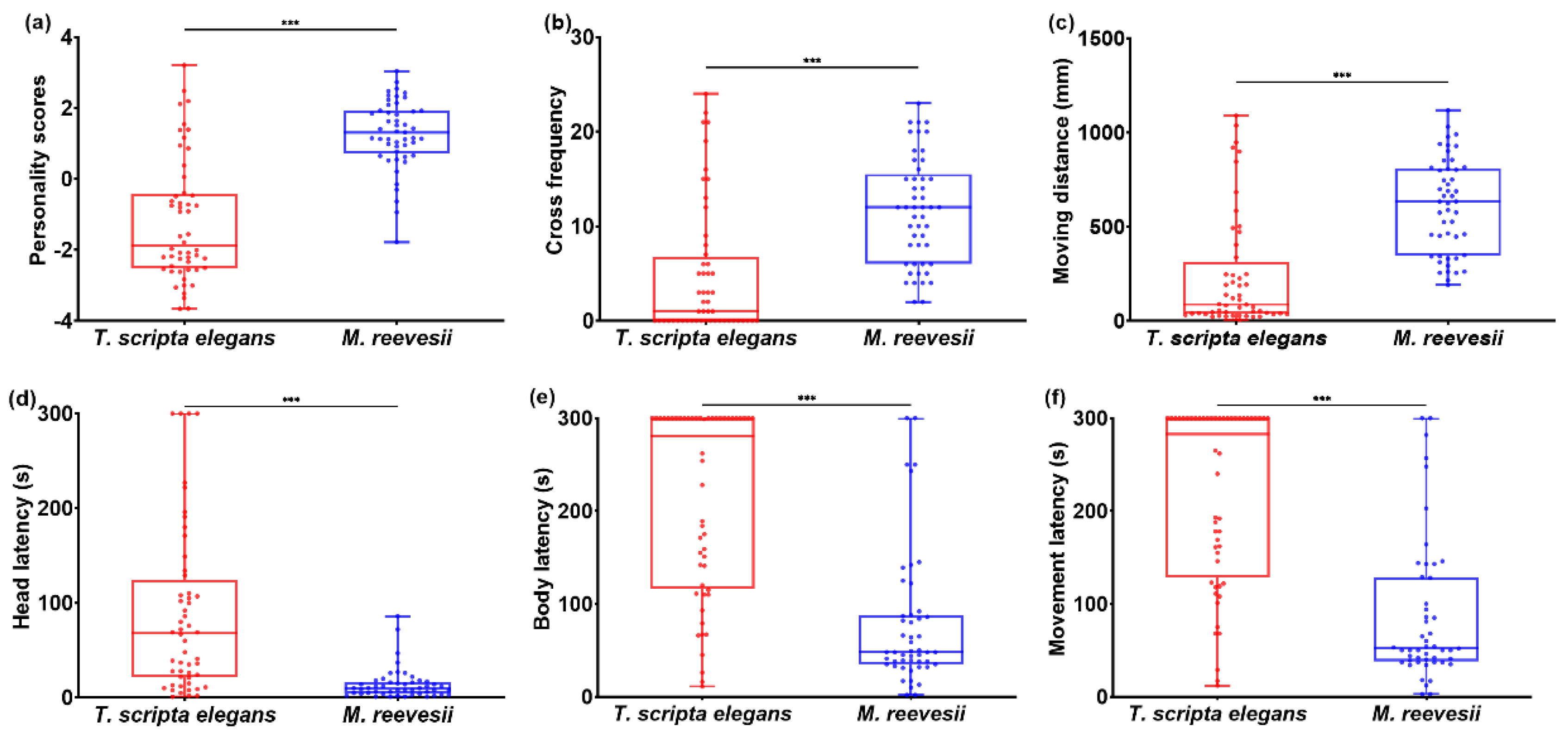

3.1. Bold-Exploration Personality

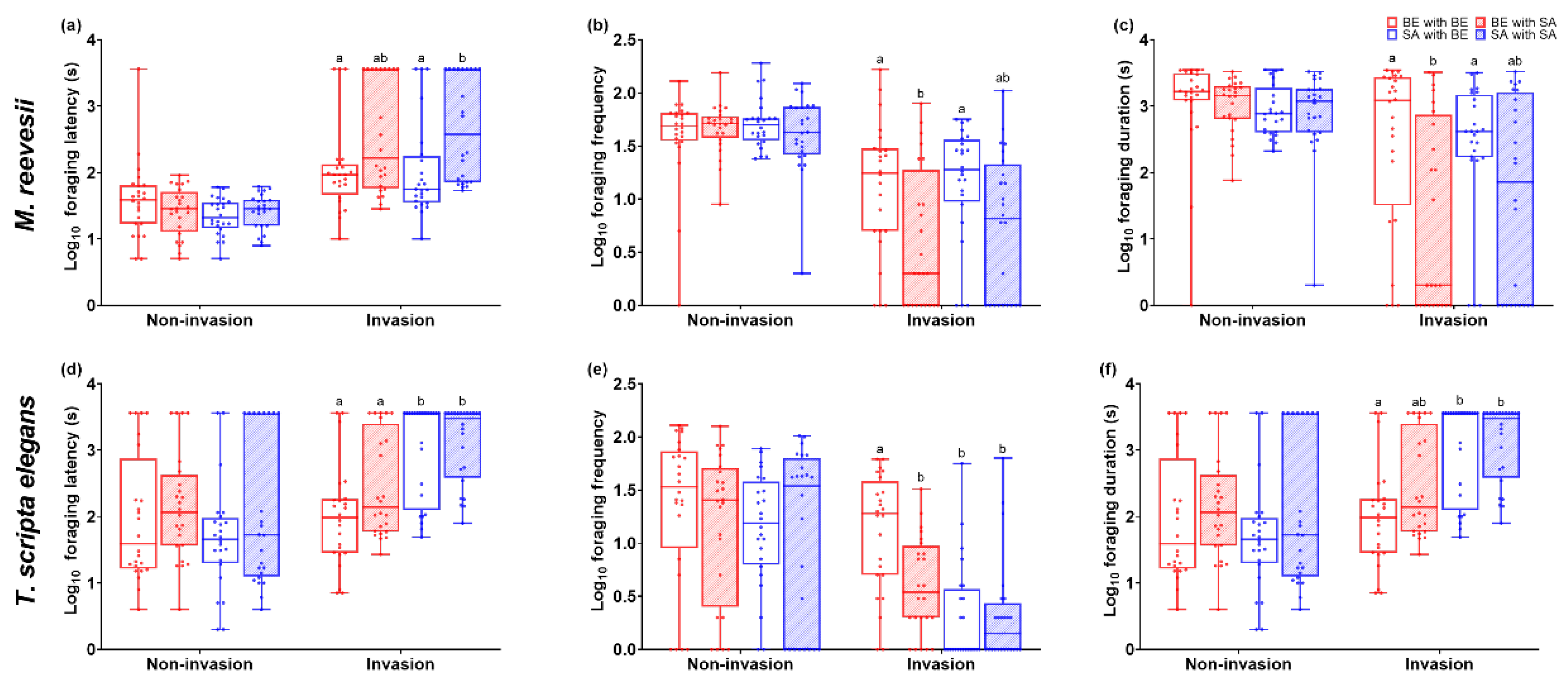

3.2. Foraging Behavior

3.2.1. Foraging Latency

3.2.2. Foraging Frequency

3.2.3. Foraging Duration

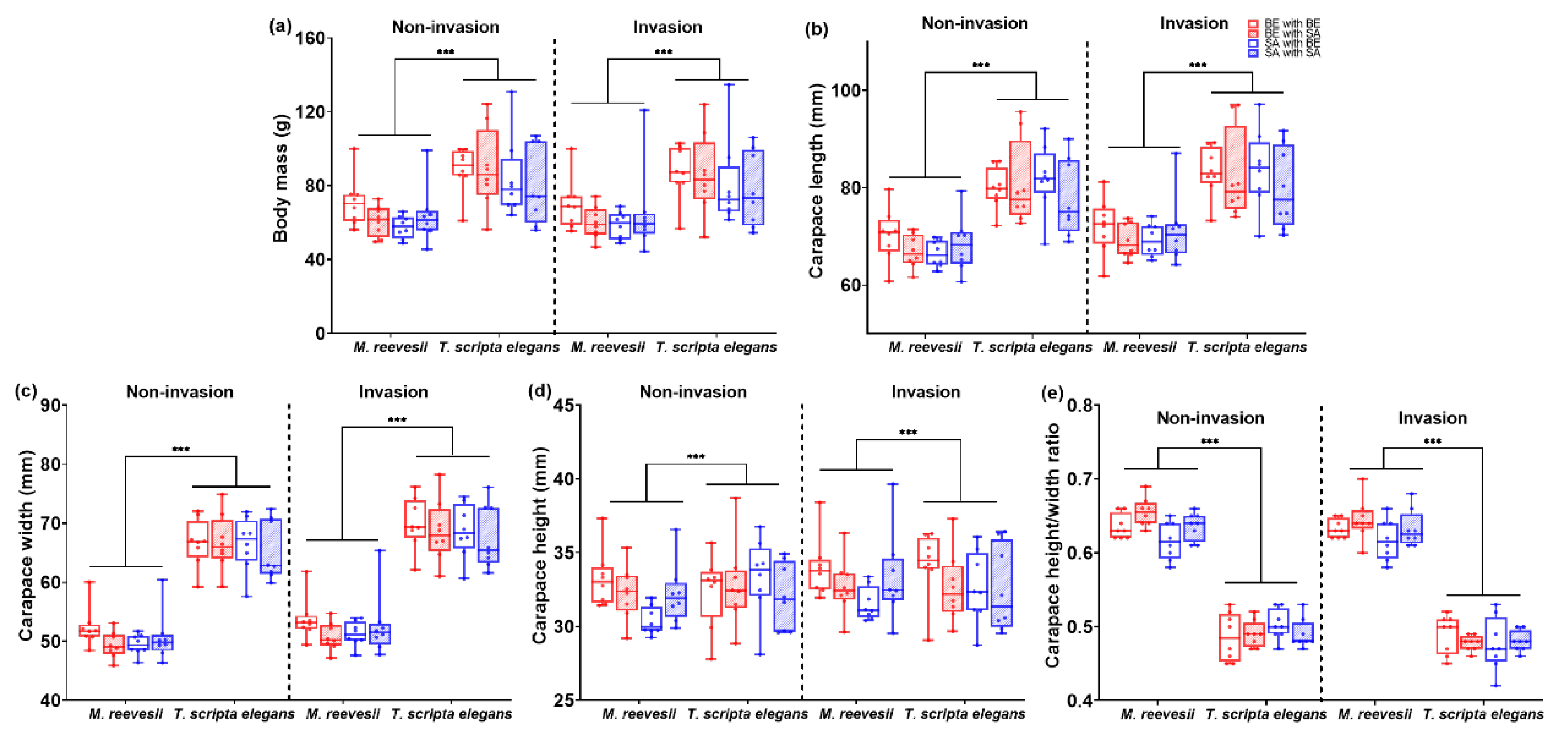

3.3. Morphology Traits

3.3.1. Body Mass

3.3.2. Carapace Length

3.3.3. Carapace Width

3.3.4. Carapace Height

3.3.5. Carapace Height/Width Ratio

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blackburn, T.M.; Bellard, C.; Ricciardi, A. Alien versus Native Species as Drivers of Recent Extinctions. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2019, 17, 203–207. [CrossRef]

- Sala, O.E.; Stuart Chapin, F.; III; Armesto, J.J.; Berlow, E.; Bloomfield, J.; Dirzo, R.; Huber-Sanwald, E.; Huenneke, L.F.; Jackson, R.B.; et al. Global Biodiversity Scenarios for the Year 2100. Science 2000, 287, 1770–1774. [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.S.; Glen, A.S.; Nimmo, D.G.; Ritchie, E.G.; Dickman, C.R. Invasive Predators and Global Biodiversity Loss. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 11261–11265. [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, B.; Clavero, M.; Sánchez, M.I.; Vilà, M. Global Ecological Impacts of Invasive Species in Aquatic Ecosystems. Global Change Biology 2016, 22, 151–163. [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Benton, T.G. Causes and Consequences of Animal Dispersal Strategies: Relating Individual Behaviour to Spatial Dynamics. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2005, 80, 205–225. [CrossRef]

- Clobert, J.; Le Galliard, J.-F.; Cote, J.; Meylan, S.; Massot, M. Informed Dispersal, Heterogeneity in Animal Dispersal Syndromes and the Dynamics of Spatially Structured Populations. Ecol Lett 2009, 12, 197–209. [CrossRef]

- Cote, J.; Bestion, E.; Jacob, S.; Travis, J.; Legrand, D.; Baguette, M. Evolution of Dispersal Strategies and Dispersal Syndromes in Fragmented Landscapes. Ecography 2017, 40, 56–73. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, W.H.; McPeek, M.A. Is Dispersal Neutral? Trends Ecol Evol 2014, 29, 444–450. [CrossRef]

- Berger-Tal, O.; Blumstein, D.T.; Carroll, S.; Fisher, R.N.; Mesnick, S.L.; Owen, M.A.; Saltz, D.; St. Claire, C.C.; Swaisgood, R.R. A systematic survey of the integration of animal behavior into conservation. Conservation Biology 2016, 30, 744–753. [CrossRef]

- del Río, L.; Navarro-Martínez, Z.M.; Cobián-Rojas, D.; Chevalier-Monteagudo, P.P.; Angulo-Valdes, J.A.; Rodriguez-Viera, L. Biology and Ecology of the Lionfish Pterois Volitans/Pterois Miles as Invasive Alien Species: A Review. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15728. [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.V.; Drake, J.M.; Jones, L.; Murdock, C.C. Assessing Temperature-Dependent Competition between Two Invasive Mosquito Species. Ecological Applications 2021, 31, e02334. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.L.; Fill, J.M.; Davies, S.J.; Louw, M.; Rebelo, A.D.; Thorp, C.J.; Vimercati, G.; Measey, J. A Global Meta-Analysis of the Ecological Impacts of Alien Species on Native Amphibians. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2019, 286, 20182528. [CrossRef]

- Ruland, F.; Jeschke, J.M. How Biological Invasions Affect Animal Behaviour: A Global, Cross-Taxonomic Analysis. Journal of Animal Ecology 2020, 89, 2531–2541. [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.D. Personality in Non-Human Animals: Animal Personality. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2008, 2, 985–1001. [CrossRef]

- Cote, J.; Fogarty, S.; Weinersmith, K.; Brodin, T.; Sih, A. Personality Traits and Dispersal Tendency in the Invasive Mosquitofish (Gambusia Affinis). Proc Biol Sci 2010, 277, 1571–1579. [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, R.A.; Badyaev, A.V. Coupling of Dispersal and Aggression Facilitates the Rapid Range Expansion of a Passerine Bird. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 15017–15022. [CrossRef]

- Malange, J.; Izar, P.; Japyassú, H. Personality and Behavioural Syndrome in Necromys Lasiurus (Rodentia: Cricetidae): Notes on Dispersal and Invasion Processes. acta ethol 2016, 19, 189–195. [CrossRef]

- Chapple, D.G.; Simmonds, S.M.; Wong, B.B.M. Can Behavioral and Personality Traits Influence the Success of Unintentional Species Introductions? Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2012, 27, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, S.; Cote, J.; Sih, A. Social Personality Polymorphism and the Spread of Invasive Species: A Model. The American Naturalist 2011, 177, 273–287. [CrossRef]

- Galib, S.M.; Sun, J.; Twiss, S.D.; Lucas, M.C. Personality, Density and Habitat Drive the Dispersal of Invasive Crayfish. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 1114. [CrossRef]

- Short, K.H.; Petren, K. Boldness Underlies Foraging Success of Invasive Lepidodactylus Lugubris Geckos in the Human Landscape. Animal Behaviour 2008, 76, 429–437. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, K.M.; Pinter-Wollman, N. Collective Responses to Heterospecifics Emerge from Individual Differences in Aggression. Behav Ecol 2019, 30, 801–808. [CrossRef]

- Santicchia, F.; Wauters, L.A.; Tranquillo, C.; Villa, F.; Dantzer, B.; Palme, R.; Preatoni, D.; Martinoli, A. Invasive Alien Species as an Environmental Stressor and Its Effects on Coping Style in a Native Competitor, the Eurasian Red Squirrel. Hormones and Behavior 2022, 140, 105127. [CrossRef]

- Winandy, L.; Denoël, M. The Aggressive Personality of an Introduced Fish Affects Foraging Behavior in a Polymorphic Newt. Behavioral Ecology 2015, 26, 1528–1536. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, S.H.; Avery, H.W.; Spotila, J.R. Juvenile Invasive Red-Eared Slider Turtles Negatively Impact the Growth of Native Turtles: Implications for Global Freshwater Turtle Populations. Biological Conservation 2015, 186, 115–121. [CrossRef]

- Polo-Cavia, N.; López, P.; Martín, J. Competitive Interactions during Basking between Native and Invasive Freshwater Turtle Species. Biol Invasions 2010, 12, 2141–2152. [CrossRef]

- 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species: A Selection From The Global Invasive Species Database. In Encyclopedia of Biological Invasions; Simberloff, D., Rejmanek, M., Eds.; University of California Press, 2019; pp. 715–716 ISBN 978-0-520-94843-3.

- Polo-Cavia, N.; López, P.; Martín, J. Aggressive Interactions during Feeding between Native and Invasive Freshwater Turtles. Biol Invasions 2011, 13, 1387–1396. [CrossRef]

- Turtle Taxonomy Working Group; Rhodin, A.G.J.; Iverson, J.B.; Bour, R.; Fritz, U.; Georges, A.; Shaffer, H.B.; van Dijk, P.P. Turtles of the World: Annotated Checklist and Atlas of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution, and Conservation Status (8th Ed.); Chelonian Research Foundation & Turtle Conservancy, 2017; ISBN 978-1-5323-5026-9.

- van Dijk, P.P. Mauremys Reevesii. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: E.T170502A97431862. 2011.

- Masin, S.; Bonardi, A.; Padoa-Schioppa, E.; Bottoni, L.; Ficetola, G.F. Risk of Invasion by Frequently Traded Freshwater Turtles. Biol Invasions 2014, 16, 217–231. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, Y.; Rao, D.; Zhou, T.; Gong, S. China’s Wild Turtles at Risk of Extinction. Science 2020, 368, 838–838. [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, H.; Tabata, R.; Hori, T.; Mitamura, H.; Arai, N. Feeding Kinematics of Freshwater Turtles: What Advantage Do Invasive Species Possess? Zoology 2014, 117, 315–318. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Kang, C.; Huang, X.; Lu, H. Differences in swimming, righting performance and heart rate in the invasive Trachemys scripta elegans and native Mauremys reevesii hatchling. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2021, 41, 7204–7211. [CrossRef]

- Kashon, E.A.F.; Carlson, B.E. Consistently Bolder Turtles Maintain Higher Body Temperatures in the Field but May Experience Greater Predation Risk. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 2018, 72, 9. [CrossRef]

- Roth, T.C.; Rosier, M.; Krochmal, A.R.; Clark, L. A Multi-trait, Field-based Examination of Personality in a Semi-aquatic Turtle. Ethology 2020, 126, 851–857. [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Derenne, A.; Ellis-Felege, S.; Rhen, T. Incubation Temperature and Satiety Influence General Locomotor and Exploratory Behaviors in the Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra Serpentina). Physiology & Behavior 2020, 220, 112875. [CrossRef]

- Reed, B.M.; Hobelman, K.; Gauntt, A.; Schwenka, M.; Trautman, A.; Wagner, P.; Kim, S.; Armstrong, C.; Wagner, S.; Weller, A.; et al. Spatiotemporal Variation of Behavior and Repeatability in a Long-Lived Turtle. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 2023, 77, 88. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, C.; Pan, X.; Storey, K.B.; Zhang, W. Distinct Metabolic Responses to Thermal Stress between Invasive Freshwater Turtle Trachemys Scripta Elegans and Native Freshwater Turtles in China. Integrative Zoology 2024, 00, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Wauters, L.A.; Mazzamuto, M.V.; Santicchia, F.; Martinoli, A.; Preatoni, D.G.; Lurz, P.W.W.; Bertolino, S.; Romeo, C. Personality Traits, Sex and Food Abundance Shape Space Use in an Arboreal Mammal. Oecologia 2021, 196, 65–76. [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, J.D. MCMC Methods for Multi-Response Generalized Linear Mixed Models: The MCMCglmm R Package. J. Stat. Soft. 2010, 33. [CrossRef]

- Sih, A.; Cote, J.; Evans, M.; Fogarty, S.; Pruitt, J. Ecological Implications of Behavioural Syndromes. Ecology Letters 2012, 15, 278–289. [CrossRef]

- Réale, D.; Reader, S.M.; Sol, D.; McDougall, P.T.; Dingemanse, N.J. Integrating Animal Temperament within Ecology and Evolution. Biological Reviews 2007, 82, 291–318. [CrossRef]

- Réale, D.; Dingemanse, N.J.; Kazem, A.J.N.; Wright, J. Evolutionary and Ecological Approaches to the Study of Personality. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2010, 365, 3937–3946. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.; Weissing, F.J. Animal Personalities: Consequences for Ecology and Evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2012, 27, 452–461. [CrossRef]

- Greene, H.W. Antipredator Mechanisms in Reptiles. In: Biology of the Reptilia, Vol. 16 ( C. Gans & R. B. Huey, Eds). In Antipredator mechanisms in reptiles.; Alan R. Liss, New York, 1988; pp. 1–152.

- Polo-Cavia, N.; López, P.; Martín, J. Interspecific Differences in Responses to Predation Risk May Confer Competitive Advantages to Invasive Freshwater Turtle Species. Ethology 2008, 114, 115–123. [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, A.; López, P.; Martín, J. Inter-Individual Variation in Antipredator Hiding Behavior of Spanish Terrapins Depends on Sex, Size, and Coloration. Ethology 2014, 120, 742–752. [CrossRef]

- Krause, J.; Loader, S.P.; McDermott, J.; Ruxton, G.D. Refuge Use by Fish as a Function of Body Length–Related Metabolic Expenditure and Predation Risks. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 1998, 265, 2373–2379. [CrossRef]

- Polo-Cavia, N.; López, P.; Martín, J. Interspecific Differences in Heat Exchange Rates May Affect Competition between Introduced and Native Freshwater Turtles. Biol Invasions 2009, 11, 1755–1765. [CrossRef]

- Sih, A.; Bell, A.M.; Johnson, J.C.; Ziemba, R.E. Behavioral Syndromes: An Integrative Overview. The Quarterly Review of Biology 2004, 79, 241–277. [CrossRef]

- Anselme, P.; Güntürkün, O. How Foraging Works: Uncertainty Magnifies Food-Seeking Motivation. Behav Brain Sci 2018, 42, e35. [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.J.; Goldizen, A.W.; Tromp, S.A. Agamas Exhibit Behavioral Syndromes: Bolder Males Bask and Feed More but May Suffer Higher Predation. Behavioral Ecology 2010, 21, 655–661. [CrossRef]

- Ballard, G.; Dugger, K.M.; Nur, N.; Ainley, D.G. Foraging Strategies of Adélie Penguins: Adjusting Body Condition to Cope with Environmental Variability. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2010, 405, 287–302. [CrossRef]

- David, M.; Auclair, Y.; Giraldeau, L.-A.; Cézilly, F. Personality and Body Condition Have Additive Effects on Motivation to Feed in Zebra Finches Taeniopygia Guttata. Ibis 2012, 154, 372–378. [CrossRef]

- Sih, A.; Mathot, K.J.; Moirón, M.; Montiglio, P.-O.; Wolf, M.; Dingemanse, N.J. Animal Personality and State–Behaviour Feedbacks: A Review and Guide for Empiricists. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2015, 30, 50–60. [CrossRef]

- Jeanniard-du-Dot, T.; Trites, A.W.; Arnould, J.P.Y.; Guinet, C. Reproductive Success Is Energetically Linked to Foraging Efficiency in Antarctic Fur Seals. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0174001. [CrossRef]

- Foraging: Behavior and Ecology; Stephens, D.W., Brown, J.S., Ydenberg, R.C., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, 2007; ISBN 978-0-226-77264-6.

- Zhou Z.; Cai S.; Liu Y.; Sun Y.; Luo L. Body temperature, thermal dependence of locomotor performance, compensatory growth, and the immunity of hatchling Red-eared turtles and Chinese pond turtles. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2016, 36, 7014–7022.

- Rankin, D.J.; Bargum, K.; Kokko, H. The Tragedy of the Commons in Evolutionary Biology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2007, 22, 643–651. [CrossRef]

- Berger-Tal, O.; Embar, K.; Kotler, B.P.; Saltz, D. Everybody Loses: Intraspecific Competition Induces Tragedy of the Commons in Allenby’s Gerbils. Ecology 2015, 96, 54–61. [CrossRef]

- Chase, I.D.; Bartolomeo, C.; Dugatkin, L.A. Aggressive Interactions and Inter-Contest Interval: How Long Do Winners Keep Winning?. Animal Behaviour 1994, 48, 393–400. [CrossRef]

- Mathot, K.J.; Wright, J.; Kempenaers, B.; Dingemanse, N.J. Adaptive Strategies for Managing Uncertainty May Explain Personality-Related Differences in Behavioural Plasticity. Oikos 2012, 121, 1009–1020. [CrossRef]

- Reader, S.M. Causes of Individual Differences in Animal Exploration and Search. Topics in Cognitive Science 2015, 7, 451–468. [CrossRef]

- Stamps, J.A.; Groothuis, T.G.G. Developmental Perspectives on Personality: Implications for Ecological and Evolutionary Studies of Individual Differences. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2010, 365, 4029–4041. [CrossRef]

- Gharnit, E.; Dammhahn, M.; Garant, D.; Réale, D. Resource Availability, Sex, and Individual Differences in Exploration Drive Individual Diet Specialization. The American Naturalist 2022, 200, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, F. Food Patch Use of Japanese Quail (Coturnix Japonica) Varies with Personality Traits. Frontiers in Zoology 2023, 20, 30. [CrossRef]

- Patrick, S.C.; Pinaud, D.; Weimerskirch, H. Boldness Predicts an Individual’s Position along an Exploration–Exploitation Foraging Trade-Off. Journal of Animal Ecology 2017, 86, 1257–1268. [CrossRef]

- Giraldeau, L.-A.; Dubois, F. Chapter 2 Social Foraging and the Study of Exploitative Behavior. In Advances in the Study of Behavior; Academic Press, 2008; Vol. 38, pp. 59–104.

- Jeffries, P.M.; Patrick, S.C.; Potts, J.R. Be Different to Be Better: The Effect of Personality on Optimal Foraging with Incomplete Knowledge. Theor Ecol 2021, 14, 575–587. [CrossRef]

- Sjerps, M.; Haccou, P. Effects of Competition on Optimal Patch Leaving: A War of Attrition. Theoretical Population Biology 1994, 46, 300–318. [CrossRef]

- Gyimesi, A.; van Rooij, E.P.; Nolet, B.A. Nonlinear Effects of Food Aggregation on Interference Competition in Mallards. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 2010, 64, 1897–1904. [CrossRef]

- Scharf, I.; Filin, I.; Ovadia, O. An Experimental Design and a Statistical Analysis Separating Interference from Exploitation Competition. Popul Ecol 2008, 50, 319–324. [CrossRef]

| Behavioral Variables | Component 1 (PC1) | Component 2 (PC 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Boldness: head latency | -0.388 | -0.470 |

| Boldness: body latency | -0.490 | -0.299 |

| Boldness: movement latency | -0.488 | -0.292 |

| Exploration: moving distence | 0.442 | -0.517 |

| Exploration: mross frequency | 0.419 | -0.580 |

| Eigenvalue | 3.50 | 1.00 |

| Total variance (%) | 70.02% | 20.09% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).