1. Introduction

The periodontal ligament (PDL) is a unique thin connective tissue that covers the root of the tooth between the dental alveolar bone and the tooth cementum. The immediate function of the PDL is to attach the tooth to the alveolar bone through a dense network of fibers that allow withstanding the forces of mastication. This ligament tissue has a complex cellular content, made up of fibroblast-like cells, osteoblasts, osteoclasts, epithelial cell rests of Malassez, cementoblasts and odontoclasts, and exhibits highly structured microstructures, such as networks of blood vessels and sensory nerve endings [

1,

2,

3]. In addition, PDL also contains mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) able to differentiate into osteoblasts, cementoblasts and fibroblasts, allowing for periodontium regeneration and tissue repair [

4,

5]. Beyond its mechanical and regenerative roles, PDL also exhibits immune regulatory functions, eliciting a regulatory immune response to face acute inflammation triggered by periodontal pathogens [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Particularly, PDL-cells have been shown to produce various cytokines and chemokines in response to different inflammatory stimuli, indicating that PDL-cells are fibroblast-like cells able to act as immune cells [

10].

While the oral cavity harbors a wide variety of pathogenic viruses, virtually nothing is known about the interplay between PDL and viral infections. Nevertheless, PDL exhibits distinct features that may facilitate viral infections, such as its cellular diversity and a vascular network intimately connected to tissue structures. Particularly, the human herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) is a common oral virus widely distributed in the human population [

11]. Over 70% of the population shed HSV-1 asymptomatically in the oral cavity at least once a month, with many individuals appearing to shed oral HSV-1 more than 6 times per month [

12]. Oral HSV-1 shedding can eventually result in a mild disease, such as herpes labialis, the vesicular lesions on or near the lips that are commonly known as cold sores [

13]. HSV-1 is also capable of causing much more serious illnesses, including herpes stromal keratitis, herpes encephalitis and disseminated neonatal infections [

14,

15]. Recent evidence also suggests a potential contribution of HSV-1 to Alzheimer’s disease [

16].

Over the past decade, several studies have highlighted the likely role of various human herpesviruses (HHVs), including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus and HSV-1, in the pathogenesis of periodontitis [

17,

18]. Recent meta-analysis and examination survey based on large cohorts of patients revealed that HSV-1 was significantly associated with periodontitis, and notably with severe periodontitis [

19,

20]. While infections of epithelial cells and plasma cells have been proposed to support EBV spread in periodontal lesions [

21,

22,

23] the mechanisms supporting HSV-1 periodontal pathogenesis are still elusive. It was well established that HSV-1 primarily exhibits tropism for epithelial cells and fibroblasts and infects skin and connective dermal tissues. Subsequently, it infects the termini of neurons and travels in a retrograde manner to the neuronal cell body, where it remains in a latent state until reactivated by different stimuli [

24,

25]. Here, we explore the hypothesis that HSV-1 may infect mesenchymal cells originated from PDL, examining the possibility that the PDL may serve as a target tissue capable of sustaining HSV-1 infection in the periodontium.

2. Results

2.1. Implementation of a PDL-Cell Model

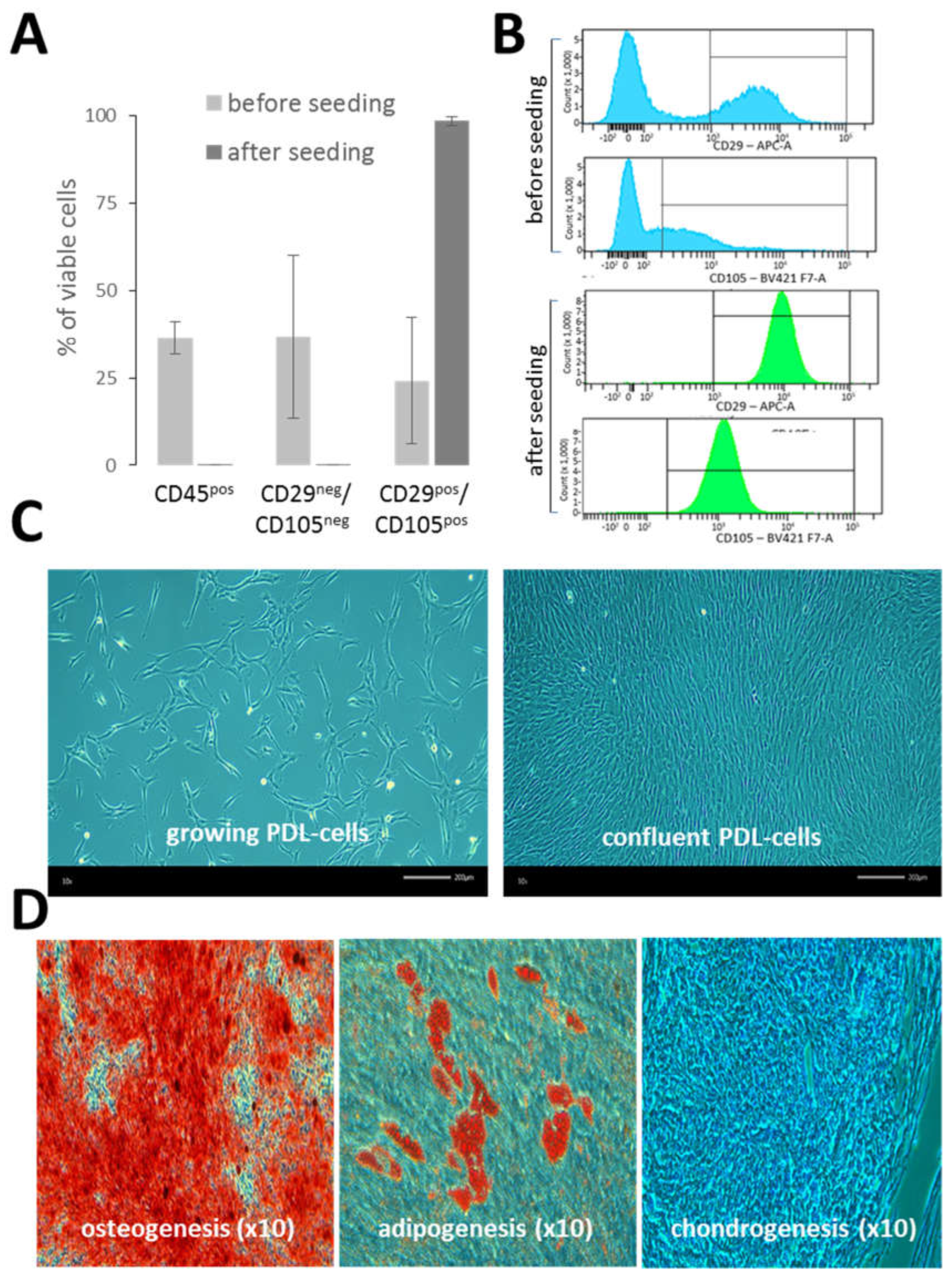

Single-cell suspensions of PDL (n = 6) were extemporaneously characterized by the flow cytometry. Overall, the cell viability was quite similar for each donor (80% ± 4.8). The PDL hematopoietic cell content (CD45) was 36.6% ± 19.1 and the mesenchymal cell content (CD29 and CD105) was 24.2% ± 18 (

Figure 1A). Apart from hematopoietic and mesenchymal cells, PDL single-cell suspensions also contained other cell types (CD45

neg CD29

neg CD105

neg) at 36.7% ± 23.4, which were not further characterized in this study. After the seeding of PDL single-cell suspensions in cell culture flasks, the phenotype of PDL-cells was monitored from early (P1) to late cell passages (P7) (in a total of n = 19 samples from 4 different PDLs). The analysis revealed a highly homogeneous and stable mesenchymal cell phenotype, predominantly comprised of cells expressing both CD29 and CD105 (98.1% ± 1.2). Of note, CD105 exhibited a wide range of intensities in PDL-cells before seeding, but after seeding, its expression became very uniform (

Figure 1B). In contrast, no major change was observed regarding CD29 expression in PDL-cells before and after seeding. As illustrated in

Figure 1C, cultured PDL-cells exhibited mostly typical fibroblast-like shape. In addition, PDL-cells cultured in specific cell differentiation media were able to differentiate into osteogenic cells, adipocytes and chondrocytes (

Figure 1D), confirming the presence of pluripotent MSCs in cultured PDL-cells and their ability to differentiate

in vitro. Each batch of PDL-cells was maintained in culture over 7 passages without a loss of growth capacity.

2.2. HSV-1 Infection of PDL-Cells

To determine whether PDL-cells were permissive to HSV-1 infection, we performed in vitro infection studies on cultured PDL-cells and PDL-fragments (

Figure 2). Infection of cultured PDL-cells induced marked morphological changes, which were observed 24 and 48 hours after the viral challenge (

Figure 2A). These morphological changes, characterized by ballooning and subsequent detachment of the dead cells, highlighted the cytolytic activity of the virus in PDL-cells. The effectiveness of HSV-1 infection of PDL-cells was demonstrated through the detection of the immediate (ICP0) and the early (ICP8) viral proteins by immunofluorescent staining (IF;

Figure 2B). ICP0 was detected in cell nuclei within 1-hour post-infection (p.i.) and ICP8 was abundantly accumulated in cell nuclei a few hours later (24 hours). These results showed that there was no delay in the onset of HSV-1 infection in PDL-cells. HSV-1 infection was also confirmed by RT-qPCR experiments to monitor viral gene expression in PDL. ICP0, ICP4 and ICP8 viral transcripts were expressed soon after infection of cultured PDL-cells (1-hour p.i.), reaching high levels of expression at 6 hours depending on the viral titer (

Figure 2C). We then investigated the permissiveness of whole fragments of PDL tissues to HSV-1. PDL-fragments (n = 3, from donors designated A, B and C) were placed in a medium containing cell-free virus for 4 hours, and HSV-1 infection was monitored by the expression of viral transcripts (

Figure 2D). An increase of ICP0, ICP4 and ICP8 expression was observed in PDL-fragments following HSV-1 exposure. However, the levels of viral infection differed significantly between donors, with pronounced infection observed in PDL-fragments from donor C and significant, but much lower, infection in PDL-fragments from donors A and B.

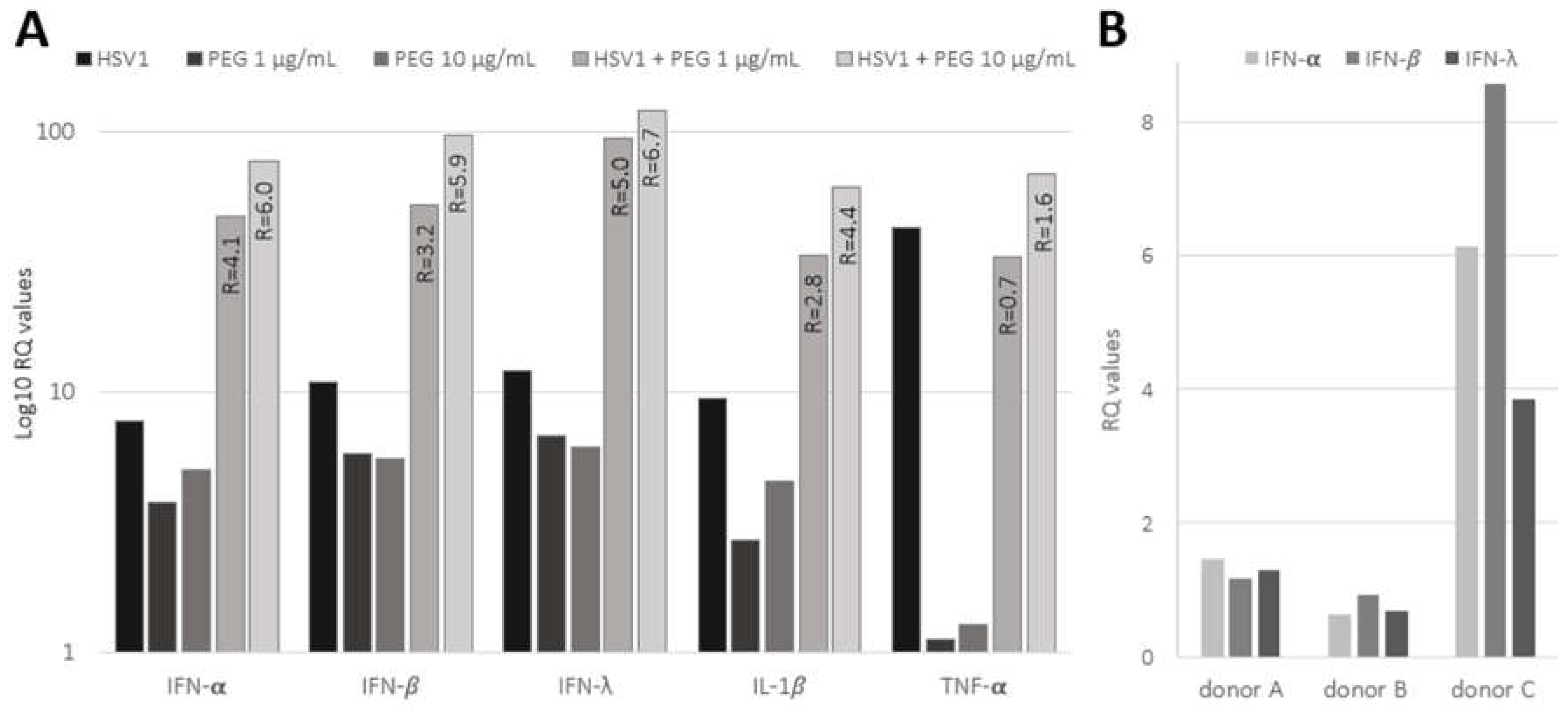

3.3. Innate Antiviral Response in HSV-1 Infected PDL Exposed to Bacterial Products

The expressions of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β TNF-α and markers of the innate antiviral response (IFN-α, IFN-β and IFN-λ) were investigated by RT-qPCR in PDL-cells infected with HSV-1 (MOI 100, 24 hours) and exposed to bacterial-derived products, such as peptidoglycan (PEG;

Figure 3A). The basal levels of IL-1β and TNF-α exhibited a significant increase (9.5- and 43-fold increase, respectively), indicating efficient induction of pro-inflammatory response in PDL-cells upon HSV-1 infection. Viral infection was also associated with a marked increase in the antiviral innate response, evidenced by about 10-fold increase in IFN-α, IFN-β and IFN-λ expression. Conversely, PEG, tested at concentrations of 1 and 10μg/ml, exhibited a slightly weaker effect on cytokines and IFN response compared to HSV-1. Notably, TNF-α barely responded to PEG. However, the combination of PEG and HSV-1 infection resulted in a remarkable synergistic effect, significantly boosting the induction of the innate immune response. As indicated in

Figure 3A, the ratio between the effect of the HSV-1 and PEG combination and the sum of their individual contributions showed a marked synergistic upregulation of IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-λ and IL-1β expression. In contrast, no or very low synergism was observed for TNF-α; its stimulation was mainly attributed to the virus.

Moreover, the IFN antiviral response (IFN-α, IFN-β and IFN-λ) was also analyzed in PDL-fragments infected with HSV-1 (

Figure 3B). The induction of IFNs remained weak at 4 hours p.i. in A and B PDLs; however, strong induction was observed in C PDL, which displayed the highest level of viral expression, as shown in

Figure 2D. These results suggested that the IFN response was related to the level of viral infection in PDL-fragments and that viral spread in the PDL was able to promote a rapid and marked inflammatory response.

3. Discussion

In this study, we established a primary cell culture model representative of mesenchymal PDL-cells. Although this culture system oversimplifies the PDL tissue complexity, it provides a reliable and suitable model for HSV-1 infection of PDL considering that, apart from neurons, the main cell tropism of HSV-1 are stromal cells. One of the main advantages of this model is the long-term maintenance of a homogeneous phenotype of PDL-derived mesenchymal cells in cell culture that retain the capacity for differentiation. Using this system, we brought the first evidence that PDL may support HSV-1 infection. HSV-1 was shown to quickly spread in PDL-cells culture promoting profound morphological changes and cytopathic effects within 24 hours. This model appears to be very convenient for supporting HSV-1 infection

in vitro, showing an efficient ability to produce large amounts of infectious HSV-1 at levels comparable to, and even higher than, those produced by Vero cells (data not shown). Moreover, HSV-1 was also able to infect PDL-fragments revealing viral permissiveness in the whole tissue. Previous studies have shown that HSV-1 invasion in oral mucosa can be restricted by mechanical barriers [

26], however, we did not observe any restriction and delay regarding HSV-1 infection in cultured PDL-cells and PDL-fragments, since immediate-early (ICP0 and ICP4) and early viral transcripts (ICP8) were expressed as soon as 1 hour after viral exposure. However, we assume that our experiments may have some limitations, considering microlesions caused by scraping and PDL detachment could have favored the viral entry and diffusion into the tissue. In whole tissue, the level of HSV-1 infection greatly varied between samples, which may reflect the differences in tissue organization and cell content among PDL samples collected by dissection from different individuals. Additionally, the presence of different factors may regulate HSV-1 infection, as suggested by previous studies demonstrating that salivary factors can modulate the infection of AG09319 gingival fibroblasts [

27].

Innate immunity is crucial for an effective host defense against pathogenic microorganisms in periodontal tissues. PDL-cells have been shown to synthesize immunomodulatory cytokines that are believed to influence the local response to infections [

6,

7,

8,

9]. We thus analyzed the innate immune response of the PDL exposed to HSV-1 and concluded that viral infection promoted an acute pro-inflammatory immune response in both cultured PDL-cells and PDL-fragments with a significant increase of TNF-α and IL-1β and induction of innate antiviral cytokines such as the type I interferons (IFN-α and IFN-β and type III interferon (IFN-λ). The level of IFN induction in response to HSV-1 appeared lower in HSV-1-infected PDL-fragments, than in cultured PDL-cells. However, this difference may be explained by the duration of viral exposure, which was adjusted to each experimental system (i.e., 4 hours versus 24 hours, respectively). Moreover, the innate response of PDL-cells was shown to be over-stimulated when cells were infected with the virus in the presence of bacterial-derived products such as PEG. Although future studies will be needed to certify synergisms using comprehensive quantitative methods, the initial results presented here clearly show that the combination of HSV-1 and PEG strongly potentiates the inflammatory response of PDL-cells. It has been proposed that the exacerbation of periodontal pathogenesis may involve synergistic interactions between periodontal bacterial dysbiosis and viral infections. Our results thus highlight the possibility that PDL may contribute to acute periodontal inflammation when exposed to different pathogen-associated molecular patterns from both bacteria and viruses.

In conclusion, the present study provides evidence to support that PDL may represent a reservoir for HSV-1 spread not only in the periodontium, but also beyond in the oral cavity. HSV-1 shedding is common in the oral cavity, and its abundance in inflammatory periodontal sites has been reported. Furthermore, PDL is densely innervated and vascularized tissue, with HSV-1 infections typically occurring via the neural route and possibly also via the hematogenous route [

28]. These factors collectively suggest a high probability of HSV-1 spreading in PDL

in vivo, although further investigations are needed for confirmation. However, presence of HSV-1 in PDL may promote severe immune dysfunction and significant alterations in PDL organization due to its cytopathogenic effect. This assumption opens the door to further investigations into the infection of periodontal tissues by HHVs and highlights the possible need for antiviral therapy. This therapy should be based on the administration of anti-HHVs drugs to patients suffering from periodontal diseases, notably periodontitis.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of PDL Fragments and PDL Single-Cell Suspensions

PDLs were collected from healthy individuals undergoing surgery for wisdom teeth removal. In total, PDLs from 9 healthy donors were used in this study, 6 for flow cytometry analysis and PDL cell seeding, and 3 for ex vivo HSV-1 infection of PDL fragments (donors A, B and C). All patients were informed of their right to oppose the use of their specimens and data for research purposes (biomedical collection N°DC-2022-5040, French Research Ministry).

Extracted teeth were immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) and antifungals (2.5 µg/ml amphotericin B and 0.5 µg/ml caspofungin) and kept at 4 °C for less than 24 hours. After 3 successive washings in PBS, rare pieces of gingival tissue still attached to the tooth were carefully removed by dissection. PDL tissues were then collected through scalpel-scraping of the mid-third of the root surface, washed with PBS and chopped into small pieces of tissue a few millimeters in size (PDL-fragments). A single-cell suspension of PDL-cells was obtained after digestion of PDL-fragments with 3 mg/ml type I collagenase and 4 mg/ml dispase II (Life Science) for 30 to 40 minutes at 37 °C with vigorous shaking every 10 minutes. The digested PDL-fragments were then passed through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon) and centrifuged at 400× g for 5 minutes. The cells were resuspended in α-MEM supplemented with 0.292 mg/ml L-Glutamine and 20% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), and then counted using a Malassez-counting chamber.

4.2. PDL Cell Culture and Differentiation

PDL single-cell suspensions were plated into 6-well plates (Falcon, Dutscher) containing α-MEM supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2.5 µg/ml amphotericin B and 0.5 µg/ml caspofungin and then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. Cells were typically plated at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well and dissociated with 0.25% Trypsin/0.02% EDTA upon reaching 80-90% confluency. The cells were subcultured in α-MEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, defined as complete culture medium (CCM). Cells from passages P1 to P7 were used for experiments. For osteogenic and adipogenic cell differentiation, PDL-cells at 80% confluency were incubated for 4 weeks, either in osteogenic medium (CCM supplemented with 50 µg/ml L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, 5 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate, 100 nM dexamethasone) or in adipogenic medium (CCM supplemented with 10 µg/ml insulin (Gibco), 100 nM dexamethasone, 1 µM rosiglitazone). Osteogenesis was demonstrated by alizarin red S staining of calcium deposits, while adipogenesis was demonstrated using oil red O staining of lipids. For chondrogenic differentiation, PDL-cells (4 × 105 cells in 20 µl of CCM) were placed into 12-well plates and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 3-hour attachment period to create micromass cultures. After gently adding additional CCM, the micromass cultures were rested for an additional 24 hours. Differentiation was carried out by adding chondrogenic medium (CCM with 50 µg/ml L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, 100 nM dexamethasone, 1× insulin-transferrin-selenium premix and 10 ng/ml TGF-β3; Peprotech). Micromasses were harvested after 3 weeks of differentiation, rinsed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde solution for 24 hours. Micromasses were embedded in paraffin and sectioned as 5 µm thick slices. The paraffin sections were then deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated and stained with alcian blue to visualize proteoglycans. The specificity of the detection procedures used to visualize differentiation was verified using non-differentiated cells as controls (not shown).

4.3. Flow Cytometry Analysis

Flow cytometry analysis of single-cell suspensions of PDL-cells and cultured PDL-cells was performed with fluorochrome-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibodies for the detection of cell surface markers (BD Biosciences). Hematopoietic cells were identified as cells expressing CD45. Mesenchymal cells were identified as stromal cells expressing the mesenchymal cell markers endoglin (CD105) and CD29 [

29]. The gating strategy of flow cytometry analysis was as follows: the region of interest (ROI) was placed on a size/structure dot-plot (FSC/SSC) to eliminate debris and residues from dissociation. Within this ROI, doublets were excluded by size and then by structure. The viability of this population was then assessed by excluding 7-AAD-positive cells. From the pool of viable cells, CD45 cells were then discriminated. Finally, the expression of CD105 and CD29 markers was assessed on CD45

neg cells. Analysis was performed using a BD FACS Canto II, and results were analyzed with FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences).

4.4. HSV-1 Infection Assays

The HSV-1 isolate used in this study was a clinical strain collected from the oral cavity of a healthy individual. It was initially propagated and characterized on Vero cells, a highly permissive kidney epithelial cell lineage from African green monkey. HSV-1 viral stock was then produced in α-MEM medium using PDL-cells as amplifying cells. The viral titer of the stock was determined by testing serial viral dilutions to define the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) that promoted a cytopathic effect on PDL-cells [

30]. The multiplicity of infection (MOI) was calculated using the Reed and Muench method.

HSV-1 infection of PDL-cells: In total, 6 different batches of PDL-cells (from different donors) were used for HSV-1 infection and analyzed with IF staining and RT-qPCRs. Sub-confluent monolayers of PDL-cells, cultured either in plastic wells (for RNA extraction) or on treated-glass slides (for IF staining), were infected with HSV-1 at different MOIs. At 1 hour, 6 hours, or 24 hours p.i., PDL-cells were rinsed twice with α-MEM medium before RNA extraction or IF staining. HSV-1 infections were also performed in the presence of 1 and 10 µg/ml of peptidoglycan (PEG) from Micrococcus luteus (Sigma-Aldrich).

HSV-1 infection of PDL-fragments: PDL-fragments were infected by direct incubation in a cell-free virus suspension (4.107 TCID50/ml) for 1 hour at 37 °C. Subsequently, PDL-fragments were washed twice by centrifugation in α-MEM medium and incubated for an additional 3 hours at 37 °C in 1 ml of α-MEM medium before the tissues were lysed for RNA extraction (RNeasy Mini kit®, Qiagen).

4.5. Immunofluorescent Staining

PDL-cells were seeded in CCM on type I collagen-coated coverslips at 50% confluency for 2 days. Adherent PDL-cells were infected with HSV-1 at MOI 100 for 1 and 24hours, then rinsed twice with 1×PBS at room temperature and fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 15 minutes. The cells were then quenched in 50 mM NH4Cl/PBS for 30 minutes and permeabilized for 4 minutes in 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS. After two 5-minutes washes in PBS, cells were incubated for 60 minutes in a 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/PBS solution to block non-specific antibody binding. The incubation with mouse primary antibodies (diluted 1:200 in 1% BSA/PBS) was carried out overnight at 4 °C. Mouse primary antibodies were HSV-1 ICP0 (11060), ICP4 (H943) and ICP8 (10A3) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and mouse IgG1 Isotype Control from Thermofisher Scientific. After three 3-minutes washes in PBS, cells were incubated with a fluorescent secondary antibody (diluted 1:1000 in 1% BSA/PBS) and co-stained with 2 µg/ml DAPI. The secondary antibody was an Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG H&L from Abcam. After a 30-minutes incubation in the dark at room temperature, the coverslips were washed three times for 3 minutes in PBS, once with distilled water and mounted onto microscope slides using Fluoromount Aqueous Mounting Medium. Image acquisition was performed using a Zeiss microscope. Unless otherwise indicated, all reagents used for differentiation and staining were from Sigma.

4.6. RNA Extraction and Reverse-Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) Analysis

PDL-cells grown on plastic wells were lysed for RNA extraction according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (RNeasy Mini kit®, Qiagen). RNA extraction from PDL-fragments was performed using a GentleMACS M Tube (Miltenyi) with the RNA_01 program (for fresh tissue) and Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit® (tissues protocol) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. RNA quantification was performed using a microvolume spectrophotometer (SimpliNano™, Biochrom).

Viral and human transcripts were detected by RT-PCR using Power SYBR

® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems™). PCR experiments were performed using QuantStudio™ 5 (Applied Biosystems™) in a 20 µl final volume using 20 ng cDNA from PDL-cells and 5.6 ng cDNA from PDL-fragments (equivalent RNA). Amplification conditions were as follows: 95 °C, 10 min; (95 °C, 15 sec; 60 °C, 1 min) cycled 40 times. Each sample was run in triplicates using specific primer sets (

Table 1) for the immediate-early (ICP0 and ICP4) and early (ICP8) HSV-1 viral transcripts, pro-inflammatory interleukin-1 beta (IL1-β), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), type 1 interferons alpha-1 and beta-1 (IFN-α and IFN-β) and type III interferon lambda 1 (IFN-λ). Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2

−ΔΔCT method, with the GAPDH gene as the reference gene and mock-infected or untreated condition as the reference sample.

Author Contributions

M. Chevalier, contributed to design, data acquisition and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; M. Ortis, contributed to design, data acquisition and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; CV. Olivieri, contributed to design, data acquisition and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; S. Vitale, contributed to design, data acquisition and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; A. Paul, contributed to design, data acquisition and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; L. Tonoyan, contributed to data interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; A. Doglio, contributed to conception, design, data interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; R. Marsault, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript. All the authors gave their final approval and agreed to be accountable for all the aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors received financial support from the University Côte d’Azur (CSI 2018) and declare they have no conflict of interest. The authors acknowledge Dr. S. Touret and Dr. P. Cochais for providing the extracted teeth.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beertsen, W.; McCulloch, C.A.; Sodek, J. The periodontal ligament: a unique, multifunctional connective tissue. Periodontol 2000 1997, 13, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanci, A.; Bosshardt, D.D. Structure of periodontal tissues in health and disease. Periodontol 2000 2006, 40, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, T.; Bakker, A.D.; Everts, V.; Smit, T.H. The intricate anatomy of the periodontal ligament and its development: Lessons for periodontal regeneration. J Periodontal Res 2017, 52, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, B.M.; Miura, M.; Gronthos, S.; Bartold, P.M.; Batouli, S.; Brahim, J.; Young, M.; Robey, P.G.; Wang, C.Y.; Shi, S. Investigation of multipotent postnatal stem cells from human periodontal ligament. Lancet 2004, 364, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatomo, K.; Komaki, M.; Sekiya, I.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Noguchi, K.; Oda, S.; Muneta, T.; Ishikawa, I. Stem cell properties of human periodontal ligament cells. J Periodontal Res 2006, 41, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, O.J.; Kim, A.R.; So, Y.J.; Im, J.; Ji, H.J.; Ahn, K.B.; Seo, H.S.; Yun, C.H.; Han, S.H. Induction of Apoptotic Cell Death by Oral Streptococci in Human Periodontal Ligament Cells. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 738047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, B.O. Mechanisms involved in regulation of periodontal ligament cell production of pro-inflammatory cytokines: Implications in periodontitis. J Periodontal Res 2021, 56, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Deng, M.; Hao, M.; Tang, J. Periodontal ligament stem cells in the periodontitis niche: inseparable interactions and mechanisms. J Leukoc Biol 2021, 110, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikeawkaew, D.; Everts, V.; Pavasant, P. TLR3 activation modulates immunomodulatory properties of human periodontal ligament cells. J Periodontol 2020, 91, 1225–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, D.; Nebel, D.; Bratthall, G.; Nilsson, B.O. The human periodontal ligament cell: a fibroblast-like cell acting as an immune cell. J Periodontal Res 2011, 46, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, C.; Harfouche, M.; Welton, N.J.; Turner, K.M.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Gottlieb, S.L.; Looker, K.J. Herpes simplex virus: global infection prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull World Health Organ 2020, 98, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, C.S.; Danaher, R.J. Asymptomatic shedding of herpes simplex virus (HSV) in the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008, 105, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, C.R.; Schofield, J.K.; Tatnall, F.M.; Leigh, I.M. Natural history, management and complications of herpes labialis. J Med Virol 1993, Suppl 1, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, R.J. Herpes simplex encephalitis: adolescents and adults. Antiviral Res 2006, 71, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verzosa, A.L.; McGeever, L.A.; Bhark, S.J.; Delgado, T.; Salazar, N.; Sanchez, E.L. Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Infection of Neuronal and Non-Neuronal Cells Elicits Specific Innate Immune Responses and Immune Evasion Mechanisms. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 644664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Wang, C.; Pang, P.; Kong, H.; Lin, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhao, J.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, T.; Guo, X. The association between herpes simplex virus type 1 infection and Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Neurosci 2020, 82 Pt A, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slots, J. Periodontal herpesviruses: prevalence, pathogenicity, systemic risk. Periodontol 2000 2015, 69, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Feng, P.; Slots, J. Herpesvirus-bacteria synergistic interaction in periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2020, 82, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arduino, P.G.; Cabras, M.; Lodi, G.; Petti, S. Herpes simplex virus type 1 in subgingival plaque and periodontal diseases. Meta-analysis of observational studies. J Periodontal Res 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Liu, N.; Gao, L.; Yang, D.; Liu, J.; Xie, L.; Dan, H.; Chen, Q. Association between human herpes simplex virus and periodontitis: results from the continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009-2014. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent-Bugnas, S.; Vitale, S.; Mouline, C.C.; Khaali, W.; Charbit, Y.; Mahler, P.; Precheur, I.; Hofman, P.; Maryanski, J.L.; Doglio, A. EBV infection is common in gingival epithelial cells of the periodontium and worsens during chronic periodontitis. PLoS One 2013, 8, e80336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivieri, C.V.; Raybaud, H.; Tonoyan, L.; Abid, S.; Marsault, R.; Chevalier, M.; Doglio, A.; Vincent-Bugnas, S. Epstein-Barr virus-infected plasma cells in periodontitis lesions. Microb Pathog 2020, 143, 104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonoyan, L.; Olivieri, C.V.; Chevalier, M.; Marsault, R.; Doglio, A. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus infection in primary junctional epithelial cell cultures. J Oral Microbiol 2024, 16, 2301199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Viejo-Borbolla, A. Pathogenesis and virulence of herpes simplex virus. Virulence 2021, 12, 2670–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinde, B. Herpesviruses: latency and reactivation - viral strategies and host response. J Oral Microbiol 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thier, K.; Petermann, P.; Rahn, E.; Rothamel, D.; Bloch, W.; Knebel-Morsdorf, D. Mechanical Barriers Restrict Invasion of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 into Human Oral Mucosa. J Virol 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Whitbeck, J.C.; Haila, G.J.; Hakim, A.A.; Rothlauf, P.W.; Eisenberg, R.J.; Cohen, G.H.; Krummenacher, C. Saliva enhances infection of gingival fibroblasts by herpes simplex virus 1. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0223299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, J.S.; Ramirez, C.; Sastre, I.; Alfaro, J.M.; Valdivieso, F. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection via the bloodstream with apolipoprotein E dependence in the gonads is influenced by gender. J Virol 2005, 79, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.N.; Bolivar-Mona, S.; Agudelo, T.; Beltran, L.D.; Camargo, D.; Correa, N.; Del Castillo, M.A.; Fernandez de Castro, S.; Fula, V.; Garcia, G.; Guarnizo, N.; Lugo, V.; Martinez, L.M.; Melgar, V.; Pena, M.C.; Perez, W.A.; Rodriguez, N.; Pinzon, A.; Albarracin, S.L.; Olaya, M.; Gutierrez-Gomez, M.L. Cell surface markers for mesenchymal stem cells related to the skeletal system: A scoping review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, M.A. Determination of 50% endpoint titer using a simple formula. World J Virol 2016, 5, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).