Introduction

Liver transplantation is the standard-care for end-stage-liver-disease. The shortage of deceased donor organs in western countries leads to extended waiting time for a transplantation[

1]. Over the past years, donor organ quality has become worse due to the scarcity of organs and the fact that most donors are elderly and have experienced a history of illness.[

2,

3]. Finally more than 200 patients per year on the waiting list died in Germany in recent years[

4].

Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) is an excellent alternative today for nearly all patients independent from the indication for transplantation and is an established addition to deceased donor liver transplantation due to organ shortage[

5,

6,

7]. While LDLT is the procedure of first choice in Asia, often due to religious and cultural backgrounds[

8], the proportion of living donations from all liver transplants performed in Germany is 5-7.5%[

9]. Here LDLT is more established for pediatric patients[

10]. Only a few centers offer a program for adult recipients[

10]. There is a total of 11 centers that offer living liver donation for adults over the years. Of these, only five centers achieve case numbers of >3 LLDT/year (Jena, Hamburg, Essen, Hanover, Regensburg)[

11].

The advantages of LDLT are versatile: LDLT might shorten the time on the waiting list and provide better donor organ quality with shorter cold ischemia time. The operation is schedulable in the context of recipient therapy like neoadjuvant treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or in the context of recipient status prior to transplantation like ongoing cholangitis for primary sclerosing cholangitis[

10].

Donor safety is still the key aspect for every LDLT program[

5,

12,

13,

14,

15]. A well-known template for an evaluation program was published by Trotter et al. in 2000, reporting on experiences with donor evaluation[

16]. The examined population of a total of 100 potential living donors at an American transplant center was examined for exclusion criteria and contraindications to donation. It was shown that an efficient but standardized psychological and medical donor evaluation is crucial.

Aim of this study was to present our evaluation process and strategy. We discuss aspects and recommendations from the literature[

15,

17] and compare our program with preexisting schemes.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of potential living donors who were evaluated for LDLT between January 2013 and December 2023 at Jena University Hospital. We retrospectively identified eligible patients by identifying all patients who were listed for liver transplantation, who died on the liver waiting list and all patients who received liver transplantation. Subsequently, the associated cases for potential living liver donations and the respective potential donors were extracted by querying the code for living liver donors according to the ICD-10 classification (Z52.6) for presentation in our outpatient consultation or for an inpatient hospital stay.

General epidemiological data of the potential recipients were collected as part of the data collection to compare whether the donor selection process differs depending on the recipient’s basic diagnosis and disease severity (

Table 1). We therefore differentiated between benign and malign underlying disease and after decompensation of liver cirrhosis. These data were collected from the digital hospital files SAP

© (SAP Deutschland SE Co. KG; Walldorf; Germany) and COPRA

© (COPRA System GmbH; Berlin; Germany).

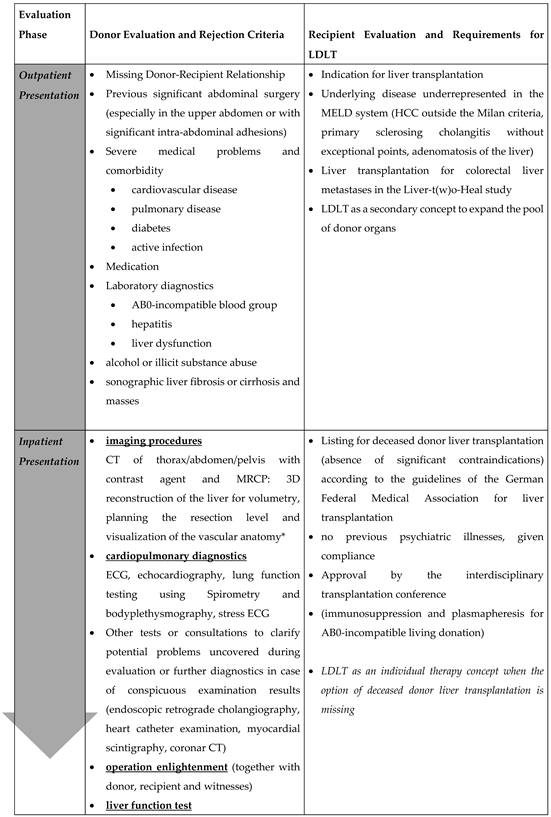

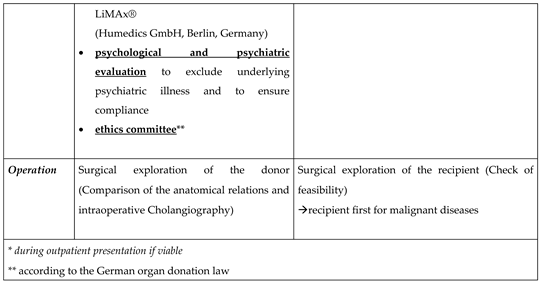

Our program’s policy entails conducting evaluations following a standardized process, wherein patients progress through three levels of assessment (

Table 2).

Outpatient Consultation

Initially patients were consultated in our outpatient department. The potential donor must clarify their voluntary for living liver donation and they must proof their close relationship to the organ recipient. That is followed by a survey of the detailed anamnesis and medical history including: the current medication, medication history, family history, allergies, previous illnesses and previous operations. The acceptance of blood transfusions and coagulation preparations should also be queried here. Additionally, the potential donors were physically examined. Laboratory tests included the following parameters: blood group, transaminases, cholestasis parameters, coagulation, retention parameters, serum electrolytes, albumin, virological status, inflammation and blood counts[

18]. An abdominal sonographic examination is performed to visualize the liver parenchyma, bile ducts and liver vessels to estimate organ size, degree of steatosis and to rule out malignancies.

Inpatient Examination

The second step takes place after inpatient admission. A repeated psychological interview is another requirement in the evaluation process. Further includes a computer tomography (CT) and a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography[

19,

20,

21] (MRCP). We used 3D reconstruction software[

22] to display the liver anatomy to plan the resection level, perform a volumetry of the split liver and to identify anatomical variants (MeVis Medical Solutions AG

®; Bremen; Germany / Synapse 3D, Fujifilm

®; Minato; Japan)[

22]. We used a non-invasive test to assess liver function of the donor (LiMAx

®; Humedics GmbH; Berlin; Germany)[

23].The cardiopulmonary suitability of the donor was also checked. If needed, any additional examinations were indicated and analyzed by a cardiologist. At the end of the process, there is the anaesthesiological assessment and the legally required surgical clarification.

To assure altruistic donation in accordance to german law donor operation takes place after a sufficient time for consideration and after a positive vote by an ethic living donation committee (anchored in the state medical association of the respective federal state).

In case of tumor indication for transplantation or technical considerations in the recipient the living donation procedure starts with the exploration of the recipient first. If this has been ruled out, surgical exploration of the donor including intraoperative cholangiography begins. Donor and recipient surgery are performed nearly parallel in two operating theatres.

Analysis

For the evaluation, the various processes should be broken down and the potential donors who presented themselves as outpatients and inpatients should be analyzed. The relationship to the recipient should also be examined according to the following groups: parents/children (grade 1), siblings/grandchildren/grandparents (grade 2), spouses (grade 3) and distant relatives/friends (grade 4).

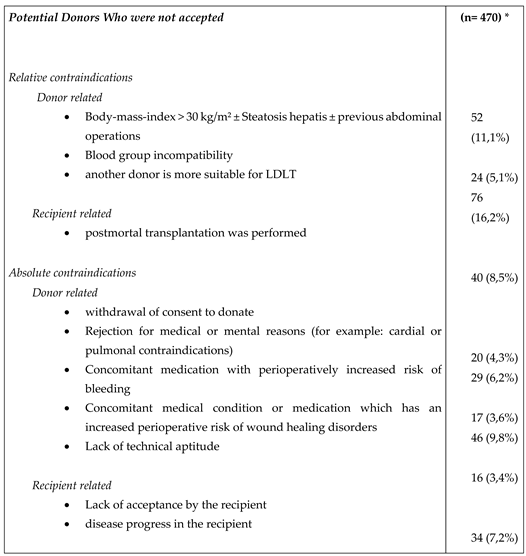

In addition, the reasons for rejecting a potential living donor should be presented and evaluated. For this purpose, we have divided the reasons for rejection into seven categories as shown in

Table 3.

In the evaluation, three groups were distinguished depending on liver function and liver disease: patients with non-cirrhotic liver disease, patients with non-decompensated and patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. In addition, the Model of End-Stage Liver Disease score (MELD) of the patients and exceptional points were recorded. In the case of hepatocellular carcinoma, the classification according to Milan criteria was used[

24].

The collected data were read out retrospectively using electronic data processing programs and in individual cases, supplemented by telephone queries to the patients. Due to the retrospective and single center approach, a good comparison with alternative evaluation methods is not possible.

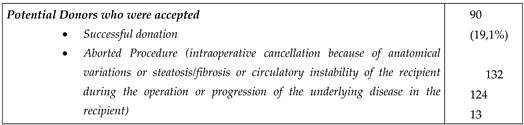

Results

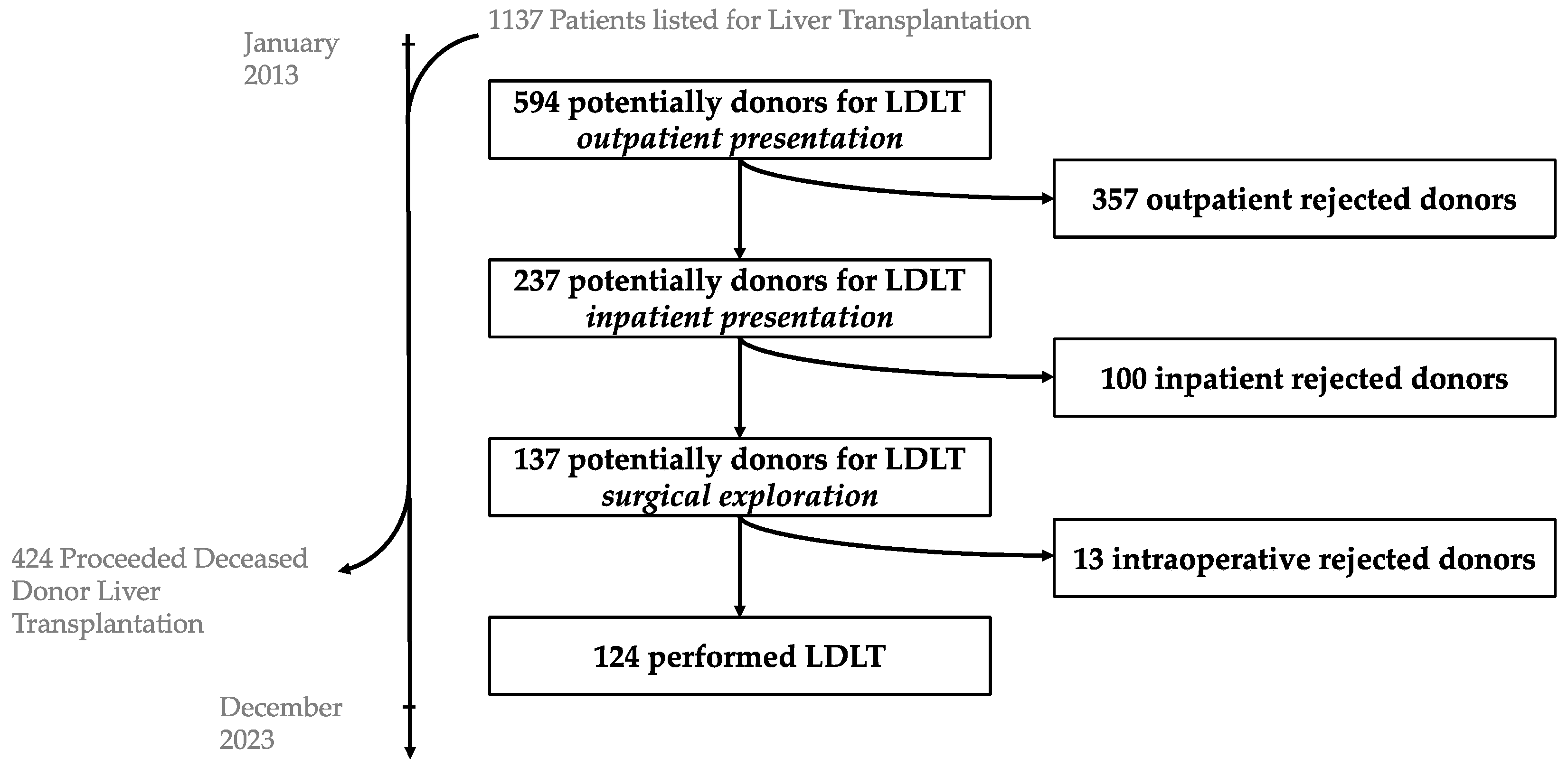

For 320 recipients, 594 potential living donors were presented at the Jena University Hospital between January 2013 and December A total of 357 of them were rejected after the outpatient presentation and 237 were admitted to a planned hospital stay for further examinations. After further diagnostics, 113 of the 237 patients were excluded. During the period 124 living donor liver transplantations were performed (

Table 1).

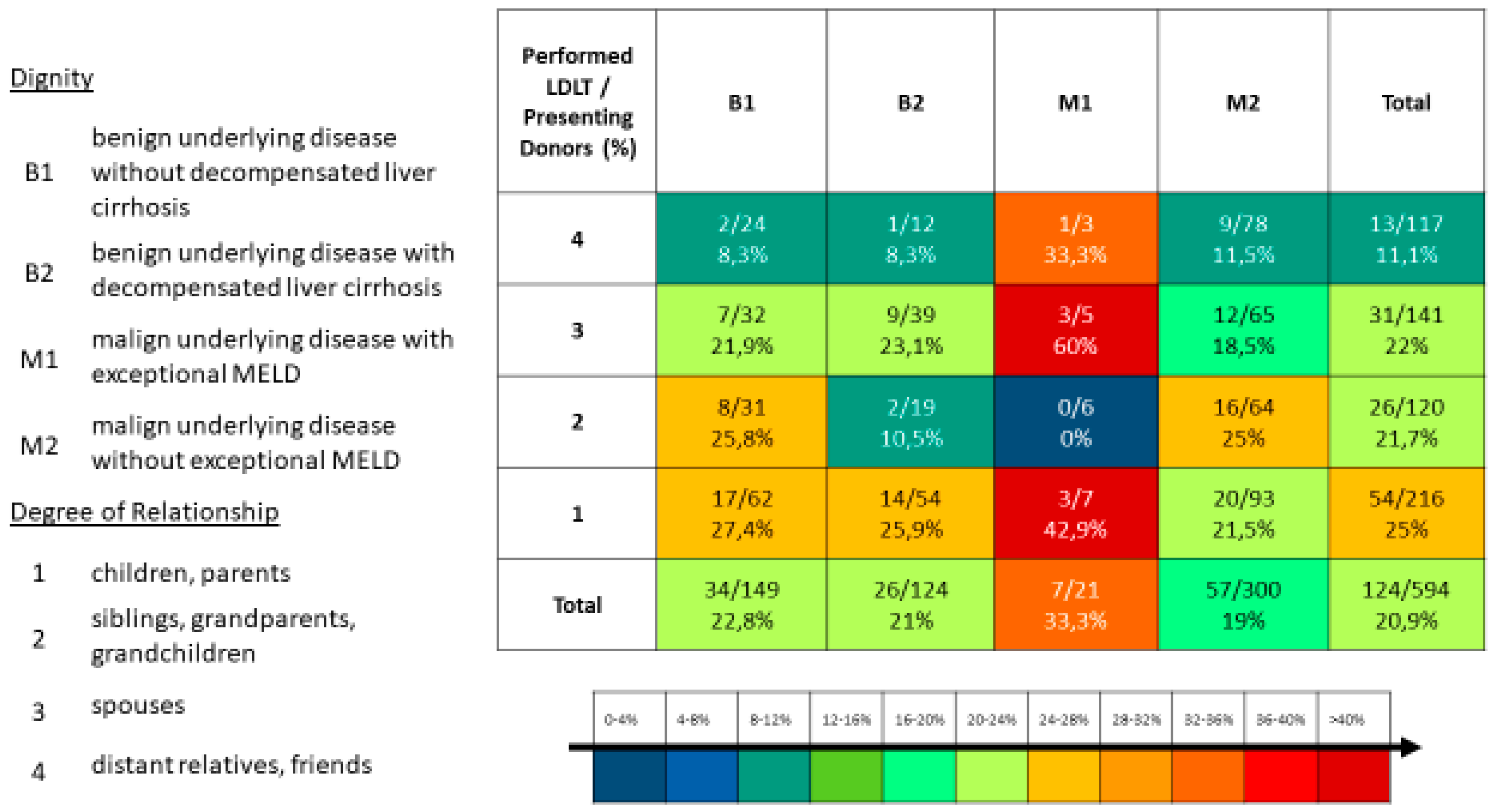

Of the 594 potential donors, 216 were parents/children (grade 1), 120 siblings/grandchildren/grandparents (grade 2), 141 spouses/partners (grade 3) and 117 distant relatives/friends (grade 4).

Table 3 displayed the reasons for a donor’s rejection.

Underlying Disease

The entity of the underlying disease in the performed living donations was malign in 60 patients and benign liver disease in 64 patients (

Table 1). Hepatocellular carcinoma accounted for the largest proportion of patients with an underlying malignancy. Of these 31 patients, seven met the Milan criteria and 24 were outside of the Milan criteria.

The proportion of recipients who presented for liver transplantation with liver cirrhosis was 74.7% (239 of 320 recipients). Living liver donations were performed significantly more often in recipients without liver cirrhosis than in patients with liver cirrhosis (49 of 125 versus 31 of 195; p <0.001).

MELD-Score and Waiting Time

In the evaluation of the patients depending on the entity, the mean labMELD score was 12.0 in patients with a malign tumor disease and 17.8 in patients with a benign disease (p<0.01). Of the patients who underwent living donor liver transplantation, 13 recipients received exceptional MELD on the waiting list according to their liver disease. 10 of these patients suffer from cancer with an average of 23.0 points (each with a hepatocellular carcinoma inside Milan). And three patients had a benign underlying disease with an average of 21.3 points (one patient with polycystic liver degeneration, one patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis, and one patient with secondary sclerosing cholangitis).

Furthermore, two patients had exceptional points on the waiting list due to a non-standard-exceptional MELD: a patient with liver metastases from a neuroendocrine tumor of the small intestine and a patient with decompensated nutritional-toxic liver cirrhosis with recurrent bacterial peritonitis and ascites fistula via an umbilical hernia.

The waiting time at Eurotransplant was shorter in patients with a malignant disease (235.3 d vs. 437.5 d; p=0.263). Significantly more potential donors presented for these recipients who were considered for a living donation (2.0 vs 1.5; p=0.023).

We have stratified all potential donors in the period from 2013 to 2023 according to the underlying diagnosis of the potential recipient and according to the degree of relationship to the recipient and highlighted the living donations that were successfully performed (

Figure 2). In our center, we treated patients with colorectal liver metastases as part of the Liver-t(w)o-Heal study[

25] with a two-stage living donor liver transplantation[

26,

27]. Has not been a standard procedure for all, we subsequently eliminated these cases from that analysis.

Figure 1.

LDLT Flowchart.

Figure 1.

LDLT Flowchart.

Figure 2.

Degree of Relationship vs. Diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Degree of Relationship vs. Diagnosis.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to map the standardized selection process for living liver donors and to work through the individual steps. This should be demonstrated using data from potential donors. In addition, the most common reasons for excluding potential donors were considered.

Our methodology uniquely emphasizes remote donor selection procedures to minimize hospitalization requirements and prioritizes initial assessments targeting factors commonly associated with exclusion from donation, thereby minimizing unnecessary examinations. Drawing upon extensive experience in evaluating living donors, we have observed that ostensibly healthy donors frequently harbor clinically significant yet previously undetected conditions.

It was important for us to show the differences in willingness to donate between potential donors, especially in the context of the underlying diagnosis of the recipient and to show the strategies for donor selection. We found that there were significant differences in donor selection depending on the recipient’s underlying diagnosis and urgency for transplantation. We have also identified relative contraindications of the donor for organ donation and explained how to deal with them. The degree of relationship between the potential donor and the recipient had influence for donor selection in the case of recipients with higher urgency. The severity of the recipients’ disease thus had a direct influence on the altruistic decision of the donors. Therefor an expansion of the potential donor pool to include more distant relatives and friends was observed.

The results have set forth that a structured evaluation of donors makes the living donation process more efficient[

6,

28,

29]. Not suitable, potential donors can already be excluded by means of an outpatient examination, thus avoiding hospitalization and unnecessary further examinations.

We have shown for which patients living donation is a good alternative to deceased organ donation. Living donation can be considered especially in the combination of decompensated underlying disease and a low MELD score or for patients with malignant disease without the option for exceptional MELD[

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

When evaluating living donation, there are significant differences depending on the underlying disease of the potential recipient. The urgency for liver transplantation, particularly in patients with cancer, is represented by the MELD-system only for standard exceptions. These patients, whose only curative treatment option is liver transplantation, would die of disease progression or be excluded from liver transplantation by progression before they were allocated an organ by the prevailing allocation system[

30,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Thus, living liver donation is a great opportunity for this patient cohort. This has two effects on the evaluation process of living donors in this patient group: compared to patients with non-malignant disease, more distant relatives and friends are considered for the donation of patients with a malignant disease. In addition, the willingness to make a living donation is usually higher for these patients, which we have seen in the significantly higher number of potential donors we examined per patient. We also see the same effect in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis in the patient cohort we examined, even if it is not statistically significant here.

A further advantage of a living liver donation is the temporal variability and plannability of the intervention. On average, patients have a significantly shorter waiting time for a liver transplant than patients who receive a conventional deceased donor liver transplant. Based on our experiences through our living liver donation program, we have established the criteria for exclusion from donation including relative and absolute contraindications donor and recipient related (

Table 4). We were also able to show that patients could already be excluded as donors when they presented themselves as outpatients (

Table 5) and that we uncovered previously unknown diseases in the course of the evaluation examinations in presumably healthy donors (

Table 6).

There are strict exclusion criteria, such as the medical suitability of the donor for living liver donation. There is no room for individual consideration here. One example is the donor’s previous cardiac disease, which entails a significantly increased perioperative risk and there are relative exclusion criteria, which are usually associated with a higher risk for the patients involved. This would be, for example, the AB0-incompatible living liver donation, which has a poorer long-term outcome for the recipient, but can be an option if there are no alternatives[

41].

A standardized model for donor evaluation was developed, which corresponds to our recommendations and shows differences to previous strategies.

Contraindications to living donation can already be detected during the outpatient presentation through simple examinations and the anamnesis and patients can thus be excluded without the need for further inpatient evaluation examinations. The anamnesis for previous illnesses and medication is of particular importance, since here, as already shown in

Table 4, clear contraindications to living donation can be found. This means that the potential donor can be spared examinations such as computer tomography with contrast agent and hospitalization. Our procedure also allows the patient’s relatives to introduce themselves for evaluation on their own initiative. Here, the clarification of the feasibility before carrying out invasive diagnostics and ultimately the clarification of the acceptance by the potential recipient is of primary importance.

Through our approach, we have worked out a few points where you have to be particularly careful to find contraindications to the donation. On the outpatient presentation, the assessment of the cardiopulmonary risk is important at the beginning and thus the clarification of whether additional diagnostics are necessary in the further evaluation process. A special consideration should concern the anamnesis of coagulation disorders of the patient and the family history.

Since we repeatedly encountered previously undiagnosed diseases during the donor evaluation process, such as findings suspected of being malignant, an interdisciplinary discussion of all findings is important so that no details are overlooked. The computed tomography should be investigated by an experienced radiologist and a demonstration of the findings of all (vascular) peculiarities with the responsible transplantation surgeon, is of particular importance. In our experience, the three-dimensional reconstruction of the vascular and biliary anatomy with planning of the resection area and volumetry for the selection of the surgical procedure (left split versus right split) has gained in importance.

In the framework of donor evaluation, initiating psychological support for both donors and recipients early on is rational to establish a psychological rapport from the outset, which endures throughout the entirety of the evaluation process, the donation procedure, and the post-donation period[

42,

43]. Such support is extended even in instances where donations do not transpire, irrespective of the cause, with the aim of collectively attending to and supporting the relatives of potential recipients(Weng 2018,Ong 2021).

In different transplant regions, subsidiarity manifests through diverse practices tailored to local contexts. For instance, centers may prioritize deceased donor allocation differently based on population demographics, organ availability, and logistical considerations. Additionally, collaborations with neighboring centers and organ procurement organizations facilitate the equitable distribution of organs within a region while leveraging collective expertise and resources.

Ultimately, subsidiarity empowers transplant centers to adapt and innovate in response to organ shortages, ensuring that patients receive timely and appropriate care while promoting fairness and efficiency in organ allocation across diverse transplant regions.

Donor Benefits

As we have evolved donor evaluation over time, we have observed in some patients that donors were excluded for the presence of multiple minor instead of one major contraindication.

Another important point in donor selection is the presence of psychiatric illnesses or the psychological stress and excessive demands of potential donors in the context of the evaluation process[

44,

45]. In these cases, we were usually also able to present additional somatic contraindications in order to link the partly subjective reasons for rejection to objective ones in order to protect the donor from further psychological and emotional stress and pressure from family or friends. Because of that we don’t see potential donors who were excluded solely on the basis of the psychological evaluation.

The evaluation of the potential living donor can also be of great importance for the patient, since, like other centers[

46], we have discovered previously undetected diseases in donors who are likely to be healthy and referred the patient to further diagnostics and therapy (

Table 5 and

Table 6).

Further Diagnostics for Donor Evaluation

In addition to the standardized program, we will in future expand our donor evaluation for patients over 50 years of age by an additional colonoscopy and for women by a gynecological examination and for men by a urological presentation. Furthermore the role of liver biopsy in donor evaluation is still controversial today. This is the only method to precisely examine the degree of steatosis or to detect other changes in the liver parenchyma[

17]. Liver biopsy is a safe investigation method, but routine liver biopsy as part of donor evaluation is still not recommended. Non-invasive diagnostics using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver and contrast-enhanced computed tomography cannot provide reliable information on the liver parenchyma, but they can provide evidence of high-grade fatty degeneration or fibrosis.

While living liver donation is considered safe with an estimated mortality rate of between 0.1 and 0.3%, the perioperative morbidity of the donor and the reduction in the donor’s quality of life are important factors in the decision-making process when selecting a donor[

47].

Conclusions

In conclusion, our living donor evaluation program demonstrates the feasibility of safely expanding the donor pool in times of organ shortage in European transplant programs. Reasons for not donating have been stated by us to provide a guidance to our evaluation program. In our opinion, the living liver donation program for adult patients can also be expanded in Europe and further concepts for diseases not previously accessible via deceased donor liver transplantation, such as colorectal liver metastases or perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, can be established study based.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.R., U.S., F.D. and F.R.; Methodology, O.R., F.D. and F.R.; Validation, O.R.; Formal analysis, O.R.; Data curation, O.R..; Writing—original draft, O.R.; Writing—review & editing O.R., L.S., A.A.-D., M.A., C.M., U.S., F.D. and F.R.; Supervision, U.S., F.D. and F.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of University Hospital Jena on 13 March 2024 (2024-3266-Data).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Roels, L. & Rahmel, A. The European experience: Strategies to meet organ shortage - Europe. Transplant Int 24, 350–367 (2011).

- Orman, E. S. et al. Declining liver graft quality threatens the future of liver transplantation in the United States. Liver Transplant 21, 1040–1050 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Mirza, D. F. et al. Policies in Europe on “marginal quality” donor livers. Lancet 344, 1480–1483 (1994). [CrossRef]

- DSO. Jahresbericht der deutschen Stiftung für Organspende 2021. https://dso.de/BerichteTransplantationszentren/Grafiken%20D%202021%20Leber.pdf (2021).

- Zhong, J., Lei, J., Wang, W. & Yan, L. Systematic review of the safety of living liver donors. Hepato-gastroenterol 60, 252–7 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Jackson, W. E. et al. Practice patterns of the medical evaluation of living liver donors in the United States. Liver Transplant 29, 164–171 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Samstein, B. & Klair, T. Living Donor Liver Transplantation: Donor Selection and Living Donor Hepatectomy. Curr Surg Reports 3, 29 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Hibi, T., Chieh, A. K. W., Chan, A. C.-Y. & Bhangui, P. Current status of liver transplantation in Asia. Int J Surg 82, 4–8 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Organspende, D. S. für. Tätigkeitsbericht 2020 - Deutsche Stiftung für Organspende. Grafiken zum Tätigkeitsbericht 2020 https://dso.de/BerichteTransplantationszentren/Grafiken%20D%202020%20Leber.pdf.

- Nadalin, S. et al. Living donor liver transplantation in Europe. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutrition 5, 159–75 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Organtransplantation, deutsche S. für. Jahresbericht Organspende und Transplantation in Deutschland 2022. https://dso.de/SiteCollectionDocuments/DSO-Jahresbericht%202022.pdf.

- Lo, C.-M. & Fan, S.-T. Living donor liver transplantation: donor selection, evaluation, and surgical complications. Curr Opin Organ Tran 6, 120–125 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Middleton, P. F. et al. Living donor liver transplantation—Adult donor outcomes: A systematic review. Liver Transplant 12, 24–30 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Goto, R. et al. Long-term risk of a fatty liver in liver donors. Ann Gastroenterological Surg (2023). [CrossRef]

- Abougergi, M. S., Rai, R., Cohen, C. K., Montgomery, R. & Solga, S. F. Trends in Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplant Organ Donation: The Johns Hopkins Experience. Prog Transplant 16, 28–32 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Trotter, J. F. Selection of donors and recipients for living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transplant 6, s52–s58 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Testa, G. et al. Optimal surgical workup to ensure safe recovery of the donor after living liver donation -- A systematic review of the literature and expert panel recommendations. Clin Transplant e14641 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Trotter, J. F. et al. Laboratory test results after living liver donation in the adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation cohort study. Liver Transplant Official Publ Am Assoc Study Liver Dis Int Liver Transplant Soc 17, 409–17 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D. et al. Accuracy of MR Imaging and MR Spectroscopy for Detection and Quantification of Hepatic Steatosis in Living Liver Donors: A Meta-Analysis. Radiology 282, 92–102 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Karakas, H. M., Celik, T. & Alicioglu, B. Bile duct anatomy of the Anatolian Caucasian population: Huang classification revisited. Surg Radiologic Anat Sra 30, 539–45 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Chaib, E., Kanas, A. F., Galvão, F. H. F. & D’Albuquerque, L. A. C. Bile duct confluence: anatomic variations and its classification. Surg Radiol Anat 36, 105–109 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Fang, C. et al. Consensus recommendations of three-dimensional visualization for diagnosis and management of liver diseases. Hepatol Int 14, 437–453 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Stockmann, M. et al. The LiMAx test: a new liver function test for predicting postoperative outcome in liver surgery. Hpb 12, 139–146 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Mazzaferro, V. et al. Liver Transplantation for the Treatment of Small Hepatocellular Carcinomas in Patients with Cirrhosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 693–700 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Rauchfuß, F., Nadalin, S., Königsrainer, A. & Settmacher, U. Living donor liver transplantation with two-stage hepatectomy for patients with isolated, irresectable colorectal liver—the LIVER-T(W)O-HEAL study. World J Surg Oncol 17, 11 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Nadalin, S., Königsrainer, A., Capobianco, I., Settmacher, U. & Rauchfuss, F. Auxiliary living donor liver transplantation combined with two-stage hepatectomy for unresectable colorectal liver metastases. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 24, 651–658 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Settmacher, U. et al. Auxilliary Liver Transplantation According to the RAPID Procedure in Noncirrhotic Patients. Ann. Surg. 277, 305–312 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H. & Olthoff, K. M. Live donor adult liver transplantation. Curr Opin Intern Medicine 7, 421–426 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Dirican, A. et al. Evaluation of Potential Donors in Living Donor Liver Transplantation. Transplant P 47, 1315–1318 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Rohland, O. et al. Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma beyond the Milan Criteria: A Specific Role for Living Donor Liver Transplantation after Neoadjuvant Therapy. Cancers 16, 920 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ivanics, T. et al. Living Donor Liver Transplantation (LDLT) for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) within and Outside Traditional Selection Criteria: A Multicentric North American Experience. Ann. Surg. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, A. B. H. et al. Living donor liver transplantation for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma including macrovascular invasion. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 148, 245–253 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-C. & Chen, C.-L. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma achieves better outcomes. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutrition 5, 415–421 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, A. B. H., Waheed, A. & Khan, N. A. Living Donor Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Appraisal of the United Network for Organ Sharing Modified TNM Staging. Front. Surg. 7, 622170 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Togashi, J., Akamastu, N. & Kokudo, N. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma at the University of Tokyo Hospital. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutrition 5, 399–407 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Müller, P. C., Kabacam, G., Vibert, E., Germani, G. & Petrowsky, H. Current status of liver transplantation in Europe. Int. J. Surg. 82, 22–29 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Moeckli, B., Majno, P., Orci, L., Peloso, A. & Toso, C. Liver Transplantation Selection and Allocation Criteria for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A European Perspective. Semin. Liver Dis. 41, 172–181 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Carlis, L. D. et al. Liver-allocation policies for patients affected by HCC in Europe. Curr. Transplant. Rep. 3, 313–318 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Artzner, T. et al. Location and allocation: Inequity of access to liver transplantation for patients with severe acute-on-chronic liver failure in Europe. Liver Transplant. 28, 1429–1440 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Sandro, S. D. et al. The European Policy for Liver Allocation in Patients Affected by Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Chir. (Buchar., Rom. : 1990) 112, 208–216 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Rummler, S. et al. Current techniques for AB0-incompatible living donor liver transplantation. World J Transplant 6, 548–555 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Uehara, M., Hayashi, A., Murai, T. & Noma, S. Psychological Factors Influencing Donors’ Decision-Making Pattern in Living-Donor Liver Transplantation. Transplantation 92, 936–942 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Jennings, T., Grauer, D. & Rudow, D. L. The Role of the Independent Donor Advocacy Team in the Case of a Declined Living Donor Candidate. Prog. Transplant. 23, 132–136 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.-C. et al. Psychological profiles of excluded living liver donor candidates: An observational study. Medicine 97, e13898 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Gordon, E. J. et al. Informed consent and decision-making about adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation: a systematic review of empirical research. Transplantation 92, 1285–96 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Park, S. et al. The living donor evaluation as a life-saving event. Clin. Transplant. 37, e14885 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Trotter, J. F., Adam, R., Lo, C. M. & Kenison, J. Documented deaths of hepatic lobe donors for living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transplant 12, 1485–1488 (2006). [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Evaluation Phases and Exclusion Process.

Table 1.

Evaluation Phases and Exclusion Process.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics.

Characteristic

|

overall potential Donors

(n = 594)

mean (SD; range) or n (%) |

Donors who were Accepted

(n = 124)

mean (SD; range) or n (%) |

Donors Who Were Not Accepted (n = 470)

mean (SD; range)

or n (%) |

Accepted vs. not accepted Donors

p - value |

| donor |

Age in years |

43.67 (12.5; 18-76) |

43.75 (12; 21-66) |

43.65 (12.6; 18-76) |

0.17 |

| Sex |

309 Women (52%)

285 Men (48%) |

73 Women (58.9%)

51 Men (41.1%) |

236 Women (50.2%)

234 Men (49.8%) |

0.09 |

| Biologically related |

336 |

80 |

256 |

0.04 |

| Relatedness grade 1 |

216 (36.4%) |

54 (43.5%) |

162 (34.5%) |

0.06

|

| Relatedness grade 2 |

120 (20.2%) |

26 (21%) |

94 (20%) |

0.81 |

| Not biologically related |

258 |

43 |

215 |

0.03 |

| Relatedness grade 3 |

141 (23.7%) |

31 (25%) |

111 (23.6%) |

0.75 |

| Relatedness grade 4 |

117 (19.7%) |

13 (10.5%) |

104 (22.1%) |

<0.01 |

| recipient |

labMELD |

14.73 |

11.95 |

15.45 |

<0.01 |

Malignom

Benign

HCC inside Milan criteria

HCC outside Milan criteria

|

312

273

21

109

|

64

60

7

24 |

248

213

14

85 |

0.82

0.54

0.15

0.75

|

|

CPT, Child‒Pugh–Turcotte Score for cirrhosis mortality; labMELD |

Table 3.

Exclusion Criteria.

Table 3.

Exclusion Criteria.

Table 4.

Rejection Categories.

Table 4.

Rejection Categories.

| |

Definition |

number of patients in our population and breakdown into different reasons for exclusion (n=)*

|

| I |

Lack of acceptance by the recipient or withdrawal of consent to donate |

54 Lack of acceptance by the recipient (a donor presented himself on his own initiative willingness for donation and the recipient declined a living donation) or withdrawal of consent to donate |

| II |

For medical or psychological reasons |

52 Body-mass-index > 30 kg/m² (n=20), Steatosis hepatis (n=22), liver cirrhosis or fibrosis (n=4), previous abdominal operations (especially in the upper abdomen) with significant intra-abdominal adhesions (n=6). |

|

46 Concomitant medical condition or medication which has an increased perioperative risk of wound healing disorders: rheumatoid arthritis (n=11) or psoriasis with methotrexate (n=4) or monoclonal antibody (n=2) or prednisolone (n=6) or azathioprine therapy (n=3). Long-standing diabetes mellitus (n=14). Factor-V-Leiden mutation (n=6). |

|

22 Cardiac contraindications: coronary heart disease (n=5), chronic heart failure (n=4), conspicuous cardiac diagnostics (poor exercise capacity or ST segment changes in the exercise electrocardiogram) (n=13) |

|

17 Concomitant medication with perioperatively increased risk of bleeding: dual antiplatelet agents (n=7), therapeutic anticoagulation (n=10). |

|

16 Diseases diagnosed during donor evaluation: suspected malignancy (n=7) or other diseases (sarcoidosis, collagenosis, colitis, neurodegenerative disease; n=8). |

|

7 Pulmonary contraindications: pulmonary disease (Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease ≥ GOLD II, n=4), conspicuous pulmonary diagnostics (spirometry shows severe ventilation disorder, n=3). |

| III |

Lack of technical eligibility |

24 Lack of technical feasibility: preoperative diagnosed anatomical variant (n=16), intraoperative cancellation of the donation in the case of an unexpected anatomical variant with a substantial risk of donor morbidity (n=8) |

| IV |

Another donor is more suitable for LDLT |

76 |

| V |

Disease progress in the recipient |

90 Disease progress in the recipient (aborted during the evaluation process or after operational exploration of the recipient (extrahepatic tumor involvement in patients with an underlying malignant disease or fulminant decompensated liver function in a benign underlying disease) |

| VI |

Blood group incompatibility (In principle, an AB0-incompatible living donation is feasible, but should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis) |

24 |

| VII |

Deceased donor transplantation was performed |

40 postmortal transplantation was performed |

| *often there are several reasons for rejection at the same time (which is why the total number of rejections in this table is higher than the number of patients). |

Table 5.

Distinction between outpatient and inpatient donor rejection.

Table 5.

Distinction between outpatient and inpatient donor rejection.

| Disease (n) |

rejected as a donor during the outpatient presentation (n) |

rejected as a donor during the inpatient presentation (n) |

| Coronary heart disease (n=5) |

0 |

5 |

| Chronic heart failure (n=4) |

2 |

2 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease ≥ GOLD II (n=4) |

4 |

0 |

| Conspicuous cardiac or pulmonary diagnostics (n=16) |

0 |

16 |

| Vascular or biliary anatomic anomaly (n=24) |

16 |

8 |

| Liver fibrosis / cirrhosis (n=4) |

1 |

3 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis (n=1) |

0 |

1 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis* (n=11) |

11 |

0 |

| Psoriasis* (n=4) |

4 |

0 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n=14) |

13 |

1 |

| Factor-V-Leiden mutation (n=3) |

3 |

0 |

| Suspected malignancy (n=7) |

0 |

7 |

| Sarcoidosis (n=5) |

4 |

1 |

| Collagenosis (n=1) |

0 |

1 |

| Colitis (n=1) |

1 |

0 |

| Neurodegenerative Disease (n=1) |

1 |

0 |

Table 6.

Distinction between donor rejection for pre-existing conditions or incidental diseases.

Table 6.

Distinction between donor rejection for pre-existing conditions or incidental diseases.

| Disease (n=total) |

Rejection as a donor due to a known pre-existing condition/disease (n) |

Rejection as a donor due to an illness that was diagnosed during the evaluation (n) |

| Coronary heart disease (n=5) |

3 |

2 |

| Chronic heart failure (n=4) |

2 |

2 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease ≥ GOLD II (n=4) |

4 |

0 |

| Conspicuous cardiac or pulmonary diagnostics (n=16) |

0 |

16 |

| Vascular or biliary anatomic anomaly (n=24) |

0 |

24 |

| Liver fibrosis / cirrhosis (n=4) |

1 |

3 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis (n=1) |

0 |

1 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (n=11) |

11 |

0 |

| Psoriasis (n=4) |

4 |

0 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n=14) |

14 |

0 |

| Factor-V-Leiden mutation (n=3) |

3 |

0 |

| Suspected malignancy (n=7) |

0 |

7 |

| Sarcoidosis (n=5) |

0 |

5 |

| Collagenosis (n=1) |

0 |

1 |

| Colitis (n=1) |

0 |

1 |

| Neurodegenerative Disease (n=1) |

1 |

0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).