1. Introduction

Psychologists has always been concerned with social problems such as violence, racial discrimination, racial stereotypes, and imitation of violent game behaviors. The possible explanation of these phenomena involve the negation of human nature, which is called dehumanization[

1]. Therefore, exploring dehumanization is helpful for attributing and analyzing negative social behaviors and their underlying psychological mechanisms. Over the past two decades, dehumanization has been more attentive[

2]. Researchers have explored potential outcomes of denied or ignored human nature, such as reduced prosocial behaviors and increased antisocial behaviors. However, The factors resulting in dehumanization has been explored uncommonly, and localized research on dehumanization in China is even rarer.

The core of human nature is social connection[

3]. Dehumanization involves the loss of human nature, the animalization or objectification of the individual, and the weakening, alienation or severance of interpersonal connections, which can exist from childhood[

4]. Object relations theory, with attachment as its core concept, points out that childhood development determines achievements of adulthood. Attachment refers to the interpersonal relationship pattern formed by an individual’s early interactions with parents. Such relatively stable interpersonal expectation and emotional behavioral style plays a key role throughout one’s life time[

5] and profoundly affects one’s development and interpersonal relationships[

6]. Based on this, this study explores whether Trait Attachment or State Attachment would affect the Dehumanization and how they work.

1.1. Adult Attachment and Attachment Style

Based on Bowlby’s attachment theory, Hazan and Shaver proposed that adult romantic relationships are also attachment relationships, called adult attachment[

7]. Adults also develop early internal working models reflecting their reactions to romantic relationships that influence their behavior in attachment-related situations, with cross-temporal stability. From this perspective, attachment has always been seen as a stable personality trait, namely, attachment style. Ainsworth originally classify attachment styles, namely secure, anxious-resistant, and avoidant[

8]. Subsequently, Bartholomew and Horowitz pointed out that the attachment system has two main dimensions: anxiety and avoidance[

9]. Anxiety refers to the fear of abandonment, but with a strong desire for closeness. Avoidance refers to the discomfort with intimacy and strong desire for independence[

6], score higher in these two dimensions is considered insecure attachment. Furthermore, based on the self-other model and Internal working model, considering the two dimensions , they proposed a four-category model of adult attachment styles, with the positive self and positive other corresponding to low anxiety and low avoidance, namely secure; The positive self but negative other model corresponding to low anxiety and high avoidance, namly dismissiving; The negative self but positive other model corresponding to high anxiety and low avoidance, namely preoccupied; The negative self and negative other model corresponding to high anxiety and high avoidance, namely fearful. Brennan et al. developed the widely used scale called Experiences of Close Relationships Scale (ECR) adopting the two dimensions(i.e., anxiety and avoidance)[

10]. As a result, constituting four types of orthogonal dimensions: high anxiety low avoidance, low anxiety low avoidance, high anxiety high avoidance, and low anxiety high avoidance.

For a long time, adult attachment styles have been controversial, centering on whether the attachment is dimensional or categorical. The dimensional approach tends to view variables from different dimensions, while the categorical approach is based on individual variations. The ECR scale is a variable-oriented method that can explore the commonalities between variables but overlooks individual heterogeneity. Latent profile analysis (LPA) is a person-oriented approach that prioritizes individual differences, dividing the research subjects into several groups and then exploring their commonalities. LPA is also suitable for calculating continuous observed variables, and its advantage is that it can report category probabilities [

11] . Therefore, this study will use the localized ECR, based on LPA and individual differences, to verify the structure of adult attachment styles (2 dimensions 4 types).

1.2. Adult Attachment and Dehumanization

Dehumanization refers to the process of denying the humanity of others[

1]. It is related to violence, racial discrimination, racial stereotypes, and imitation of violent game behaviors, which may reduce prosocial behaviors and increase antisocial behaviors. To explore the commonity of individual conflicts, Haslam et al. proposed a dual model of dehumanization, which includes dehumanization of unique human nature and dehumanization of general human nature. When unique human nature is denied, individuals will be seen as animals (animalistic); When general human nature is denied, individuals will feature lacking cognitive flexibility and warmth (mechanistic)[

12]. And he also distinguished between self-dehumanization and other-dehumanization. Self-dehumanization refers to the evaluation and recognition of one’s own dehumanization, while other-dehumanization refers to the evaluation of others[

12].

The core of human nature is social connection[

3]. Attachment is a close emotional bond bridging individuals and others, which not only benefits the individuals, more importantly, can promote interactions with others and their prosocial behaviors. Lack of humanity may lead to alienating oneself from society and denying the ability to establish social connections with others. Having unhealthly social relationships, such as the experiences when individuals have feelings of frustration and ignorance or lack feelings of belonging, can lead to a sense of self-dehumanization[

13,

14]. Insecure attachment patterns are formed by long-term neglect or harm, and the development of low self-esteem in social relationships. Although the relationship between dehumanization and adult attachment has not been clarified, whereas, attachment, working as an individual’s initial and lifelong social relationship may be closely related to dehumanization.

1.3. State Adult Attachment

Attachment styles have been conceptualized as stable personality traits[

15] . However, attachment styles can also be modified and developed as new relationships and new experiences emerge, and their fluctuations exist independently of trait attachment styles[

16]. Relationships in specific contexts can activate specific attachment schemas, such specific schemas can temporarily override trait attachment schemas and influence one’s perceptions, expectations, and behaviors [

17].

Based on the volatility of attachment styles, attachment priming is a method that can activate attachment system under certain contextual conditions and examine one’s current attachment status and its influencing factors, namely, state attachment. The commonly used method is Secure Attachment Priming (SAP), which presents secure attachment-related stimuli or asks participants to imagine or recall secure attachment-related feelings, so that the individual temporarily obtains a series of positive responses consistent with the secure attachment style, such as eliminating threats, relieving distress, gaining a sense of love , comfort, and attachment security [

18], thereby activating one’s secure attachment representation. Therefore, it can be inferred that under attachment priming, the individual’s State Secure Attachment will be temporarily increased, making them share more willingness to maintain stable relationships with others, more attention to the needs of others, and promote their prosocial behaviors, thereby reducing the level of dehumanization.

1.4. The Present Study

In summary, this study aims to explore the relationship between adult attachment and dehumanization from the perspectives of trait adult attachment and state adult attachment. Study 1 uses latent profile analysis to verify the four types of adult attachment and explore the differences in the impact of different types on dehumanization. Study 2 aims to explore the relationship between state adult attachment and dehumanization by priming participants’ secure through a Recall Writing Task. To clarify the analysis further, this study proposes the following research hypotheses:

H1: There are four latent categories of adult attachment.

H2: Different potential categories of adult attachment have different effects on dehumanization.

H3: State adult attachment significantly predicts dehumanization.

2. Study 1

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Participants

Participants were N = 705 Chinese university students (female: 63.1%; ranging from 18 to 30 years of age) enrolled through online platforms. The instructions informed participants of the research purposes, principles of voluntary participation and security, after completing the questionaires, each one will receive corresponding compensation.

2.1.2. Measures

Experiences of Close Relationships (ECR) Scale: Developed by Brennan et al. [

19], revised by Li Tonggui and Kato Kazuo[

20], with a total of 36 items(7-point scale,1=strongly disagree 7=strongly agree). Two dimensions are included: anxiety and avoidance. Each dimension has three sub-dimensions respectively, higher score of the two dimension indicating high level of the corresponding type. In this study, the Cronbach’s α value for the two dimensions were 0.85 and 0.82 , and the total was 0.91.

Perceptions of Humanness Scale: Developed by Bastian et al. [

21], revised by Chen Zhaoyang et al. [

22], with a total of 16 items(7-point scale, 1=very inconsistent, 7=very consisitent). Two sub-scales are included: self-humanization and other-humanization, each with two sub-dimensions: human nature and human uniqueness. The Cronbach’s α value for the two sub-scales were 0.80, 0.82 respectively and the total was 0.87.

2.2. Statistical Methods

We first computed descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations among the study variables(using SPSS 28.0). Then, latent profile analysis of adult attachment was performed(using Mplus 8.3) to explore the latent categories and distribution. Next, we conducted a series of analyses of variance (ANOVA)(using SPSS 28.0)to examine effects of adult attachment on dehumanization of different level. Finally, binary logistic regression analysis was carried out to investigate the predictive effects of gender, grade, only-child status, and family origin on adult attachment among college students.

2.3. Results

2.3.1. Common Method Bias

Using Harman’s single-factor test, results showed that there were 8 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the variance explained by the first factor was 22.91%, less than 40%, indicating that there was no severe common method bias.

2.3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

With gender, grade, only-child status, and family origin variables as controlled variables, avoidance, anxiety, self-dehumanization, other-dehumanization were all significantly positively correlated in pairs(

Table 1).

2.3.3. Latent Profile Analysis

We use the six sub-dimensions of the attachment scale as indicators (1, 2, 3 representing the avoidance, 4, 5, 6 representing the anxiety), latent profile analysis was to verify how many the categories of attachment types are(from 1 to 6). In terms of model fit indices, for the best class solution, we considered (1) the lower Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and sample-size-adjusted BIC(SSA-BIC), (2)an entropy≥0.8, and (3) a significant Lo–Mendell–Ruben (LMR) and bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT; [

23]).

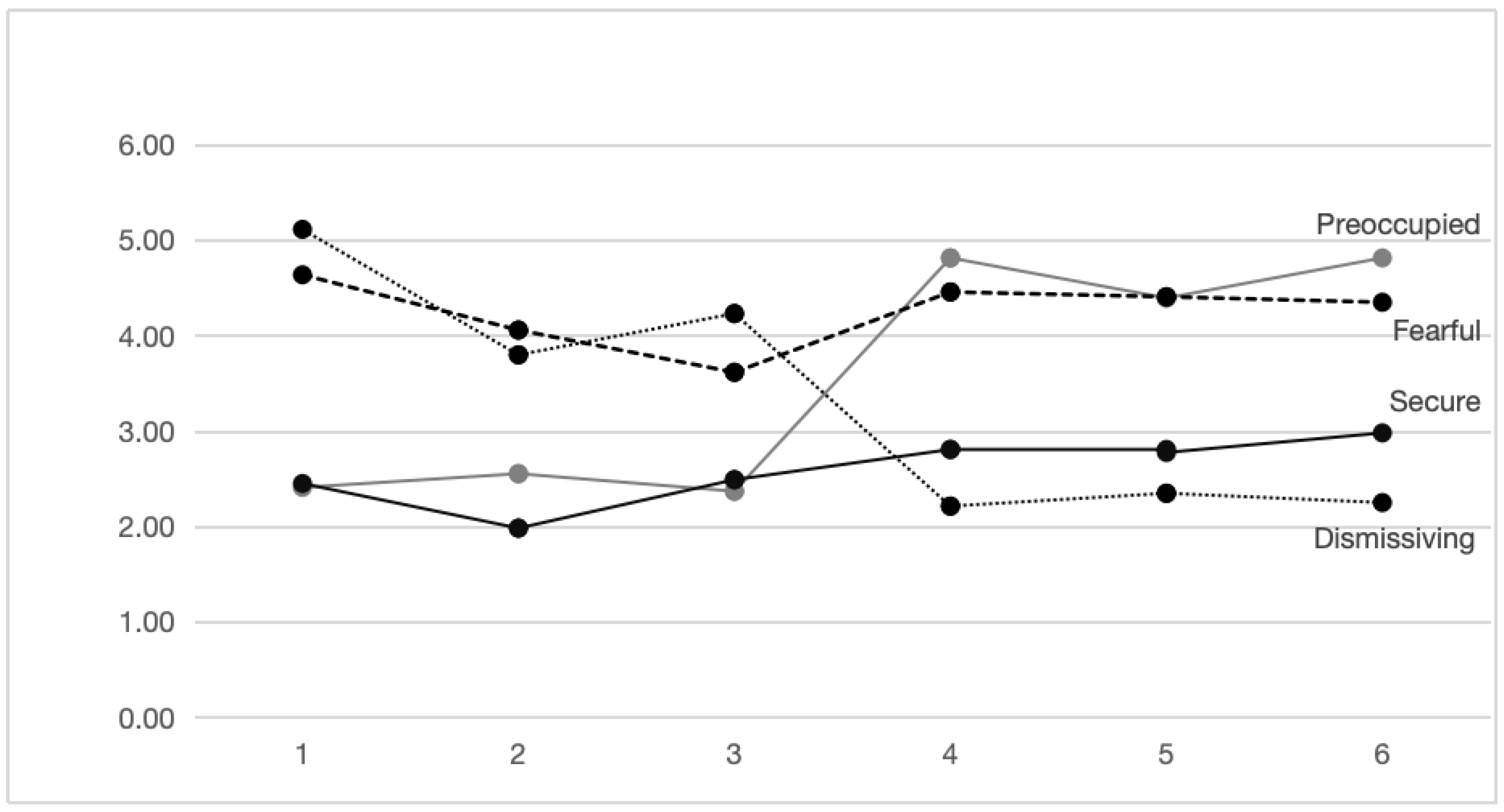

The results showed (

Table 2) that as the number of category ranges(from 1 to 6), AIC, BIC, and SSA-BIC gradually decreased, and BLRT and LMR were significant in the four-category model, with an Entropy value of 0.86 (>0.8), indicating better classification effect. Therefore, adult attachment could be classified into four categories. From the latent profile plot (

Figure 1), It’s obvious that the four categories correspond to the four types put forward by Bartholomew and Horowitz: preoccupied (low avoidance-high anxiety), secure (low avoidance-low anxiety), fearful (high avoidance-high anxiety), and dismissiving (high avoidance-low anxiety)[

9].

2.3.4. ANOVA

We conducted One-way ANOVA to examine the differences in self-dehumanization and other-dehumanization of the latent classes of adult attachment. The results showed that the latent classes of adult attachment had a significant effect on self-dehumanization, F (3,705) = 64.78, p<0.001. The post-hoc analysis found that: The fearful had the highest score on self-dehumanization, and it was significantly different from the secure and preoccupied(p< 0.001). The secure, fearful and dismissive differed significantly in self-dehumanization (p<0.001). The fearful and dismissive differed significantly in self-dehumanization(p=0.022). However, the preoccupied and dismissive did not differ significantly in self-dehumanization(p = 0.996). The four attachment classes also showed significant differences in other-dehumanization(F (3,705) = 42.16, p<0.001).

Similar to the self-dehumanization findings, the post-hoc analysis revealed that: The fearful had the highest score on other-dehumanization, and it differed significantly from the secure, preoccupied, and dismissive (

p<0.001 for all). The preoccupied and fearful also differed significantly in other-dehumanization (

p=0.038). The preoccupied and dismissiving did not differ significantly in other-dehumanization (

p= 0.995)(

Table 3,

Figure 2).

2.3.5. Logistic Regression Analysis

To further explore the relationship between sub-types of adult attachment and self-dehumanization and other-dehumanization, self-dehumanization was divided into 2 groups, group1(high level of self-dehumanization)(>24) and group2(low level of self-dehumanization)(≤24) based on the average score. Similiarly, other-dehumanization was divided into 2 groups too, group3(high level of other-dehumanization)(>26) and group4(low level of other-dehumanization)(≤26) based on the average score.

Then, using Binary logistic regression to assess the impact of different categories of adult attachment on self-dehumanization and other-dehumanization. Controlled variables are gender, grade, only-child status, and family origin. The results showed that about the self-dehumanization model, family origin (p=0.014) and the latent categories of adult attachment (p<0.001) were significant. Urban university students had a lower probability(0.65times) of self-dehumanization compared to rural university students (p=0.014). The probability of self-dehumanization in the secure was lower than that in the dismissiving(0.30times)(p<0.001), while the fearful had a higher probability( 0.30 times) of self-dehumanization compared to the dismissiving(p<0.001).

About the other-dehumanization model, gender (

p=0.010), grade (

p=0.007), and the latent categories of adult attachment (

p<0.001) were significant. Males had a higher robability(1.58times) of other-dehumanization compared to females (

p=0.010). Junior students had a lower probability of other-dehumanization(0.52times) compared to graduate students (

p=0.007). The probability of other-dehumanization in the secure was lower than in the dismissiving(0.33times)(

p=0.002), while the fearful had a higher probability of other-dehumanization(2.06 times) compared to the dismissiving(

p=0.028)(

Table 4).

3. Study 2

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants and Procedure

Participants were N = 281 Chinese university students (female: 47.3%; ranging from 18 to 30 years of age) enrolled for an online experiment. Participants were randomly divided into 2 groups, group1(secure priming)had 143 participants and group2(neutral priming)had 138 participants. Different instructions were given to the two groups based on the materials of Recall Writing Task. After 2 minutes, participants were asked to complete five items related to the Recall Writing Task. Subsequently, assess the effectiveness of the secure attachment priming and writing. Finally, participants completed the State Adult Attachment Scale and the Humanization perception Scale. Each participants would receive compensation after the experiment.

3.1.2. Measures

Recall Writing Task priming Materials: participants were primed for secure attachment or neutral attachment using the Recall Writing Task. Instructions for the group1: „please recall a person intimate with you...” and „carefully recall their appearance and the feelings when you get along with him/her, then, complete the following items.” Instructions for the group2: „please recall an unfamiliar person...” and „carefully recall their appearance and the feelings when you get along with him/her, then complete the following items” [

24].

Effectiveness Assessment Tool for Secure Attachment Priming: The effectiveness of the Secure Attachment priming(Total score≥4)was assessed by five words that could convey the feeling of secure attachment, namely secure, warm, caring, supportive, intimate[

24]. Participants rated their feelings on five items(5-point scale, 1 = not at all, 5 = very much)after completing the Recall Writing Task. The Cronbach’s α was 0.89.

Writing Effectiveness Assessment Tool: According to Mikulincer et al. [

18], the effectiveness of Writing Task includes vividness (5-point scale: 1 = very vivid, 5 = not vivid at all) and ease (5-point scale: 1 = very easy, 5 = not easy at all).

State Adult Attachment Measure (SAAM): The SAAM( 7-point scale,1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), developed by Gillath et al. [

15] and revised by Ma Shucai et al. [

25], consisting 21 items being divided into three dimensions: security, avoidance, and anxiety. Higher scores in 3 dimension indicate different state attachment type. The Cronbach’s α for the three dimensions were 0.86, 0.91, 0.85 respectively and the total was 0.83.

Humanization Perception Scale: Same as in Study 1 (α = 0.87, 0.87, 0.92).

3.2. Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were conducted for each variable(Using SPSS 28.0). Independent sample t-tests were performed to compare the differences in security and scores of Writing Task effectiveness between the two groups. Then, attachment types were classified into 3 types, and multifactor ANOVA was conducted to examine the differences in dehumanization across 3 attachment types between the two groups, followed by a simple effects test. Finally, using Regression Analysis to test the predictive effect of state adult attachment on dehumanization.

3.3. Results

3.3.1. Common Method Bias

Harman’s Single Factor Test was used to check the common method bias. The results showed that there were eight factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the variance explained by the first factor was 27.43%, which is below the standard(<40%), indicating that there wasn’t excessive common method bias in this study .

3.3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis for each variable are presented(

Table 5). The correlations between security and avoidance, anxiety and self-dehumanization, anxiety and other-dehumanization were not significant, while others’in pair were significant.

3.3.3. Priming Effectiveness Test

The scores of group1 were higher than those of group2 in scores of security (

p<0.001)(average score>4). However, there were no significant differences between the groups in vividness (

p=0.370) and ease (

p=0.219)(

Table 6), indicating that the priming was effective.

3.3.4. Difference Test

Considering previous research on the standards of attachment type classification[

26,

27,

28], participants with higher scores than the average of security and lower than the averages of avoidance and anxiety were classified as secure. Those with lower scores than the average of security and anxiety but higher than the average of avoidance were classified as avoidance. Participants with lower scores than the average of security and avoidance but higher than the average of anxiety were classified as anxiety. The scores of self-dehumanization and other-dehumanization would be compared among the attachment types in the two groups(

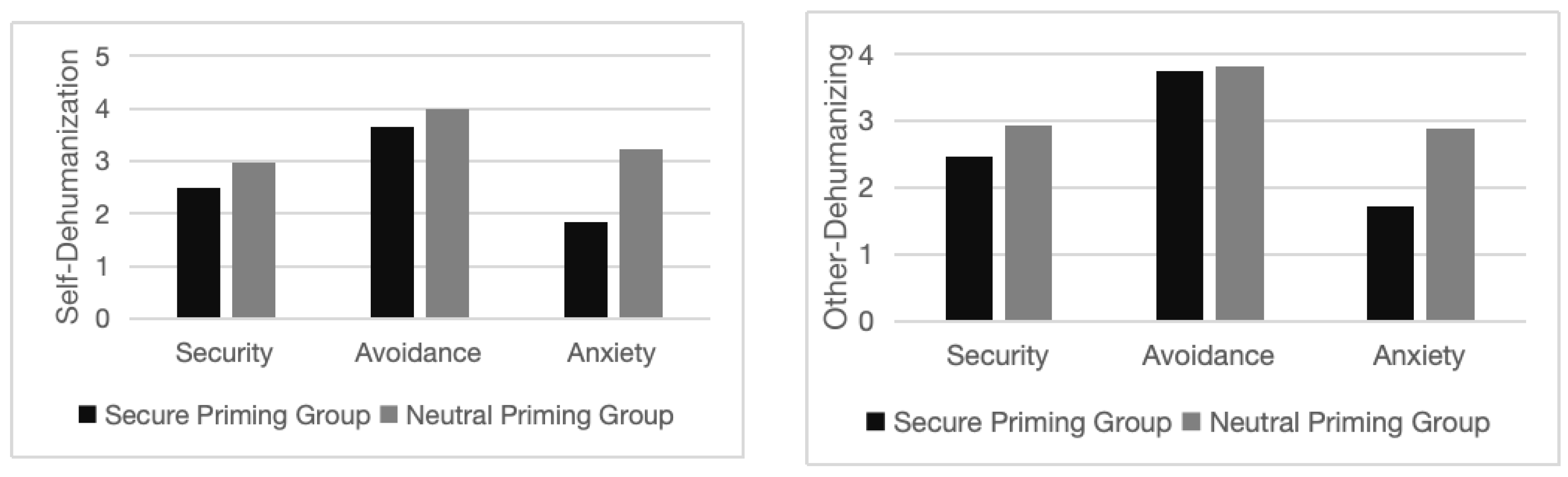

Table 7, Figure2) .

Next, a multifactor ANOVA was conducted. Independent variables are Group(secure priming, neutral priming) and Attachment Types (security, avoidance, anxiety). Dependent variables are self-sehumanization and other-dehumanization. The results (see

Table 8) showed that the main effects of group and attachment types on both self-dehumanization and other-dehumanization were significant (

p<0.001). The interaction effect of group and attachment types on self- dehumanization(

p=0.096) was not significant, while the interaction effect on other-dehumanization(

p=0.021) was significant.

Moreover, Simple Effects Tests showed that for the secure priming group, the avoidance had higher score in self-dehumanization than the security and anxiety (p<0.001), with no significant difference between the anxiety and security (p=0.104). The avoidance also had higher score in other-dehumanization than the security and anxiety(p<0.001), and the secure had higher score than the anxiety(p=0.012).

In the neutral priming group, the avoidance had higher score in self-dehumanization than the security and anxiety(p=0.001; p=0.003), with no significant difference between the anxiety and security(p=0.999). The avoidance also had higher score in other-dehumanization than the security and anxiety (p<0.001), with no significant difference between the anxiety and security(p=0.718).

3.3.5. Regression Analysis

A linear regression analysis was conducted. Independent variables are security, avoidance, and anxiety, and dependent variables are self-dehumanization and other-dehumanization. security and avoidance both had significant predictive effects on self-dehumanization and other-dehumanization (p<0.001), while anxiety did not show a significant effect(see

Table 9).

4. General Discussion

4.1. Potential Categories of Adult Attachment

The results of the latent profile analysis confirmed hypothesis 1, indicating that dividing the participants into four categories is appropriate, supporting the four-type attachment theory [

9]. Thus, the four types can be classified as follows: preoccupied (low avoidance-high anxiety), secure (low avoidance-low anxiety), fearful (high avoidance-high anxiety), and dismissiving (high avoidance-low anxiety). The proportions of four types are 0.22, 0.26, 0.45, and 0.07, respectively. Insecure attachments (fearful, preoccupied, and dismissive) account for 78%, the fearful being the most prevalent and the dismissive type the least. Distributions above is similar to the findings of some Chinese research(e.g., [

29,

30] ).

This highlights we need to pay more attention to the students(aged 17 to 22) with Insecure attachment, particularly the fearful. The dismissiving type is easily overlooked and requires careful identification. These results provide theoretical support for the localization of the person-oriented four-type adult attachment styles in China, facilitating further research and intervention efforts.

4.2. Relationship Between potential Categories of Adult Attachment and Dehumanization

The results of the variance analysis show significant differences in dehumanization among the potential categories of adult attachment. The fearful scored the highest in both self-dehumanization and other-dehumanization, while the secure scored the lowest. The preoccupied and dismissiving fell in between. Logistic regression analysis results indicated that the probability of dehumanization is lower in the secure and higher in the fearful.

These results were consistent with the variance analysis, suggesting that security is associated with lower levels of dehumanization, while fearful is associated with higher levels.This confirms hypothesis 2, that the impact of different potential categories of adult attachment on dehumanization is different.

Specifically, the characteristics of security is having positive psychological models and confidence in oneself and others and self-esteem without extreme interpersonal barrier. Previous research also indicates that secure attachment might be one of the key factors affecting dehumanization[

4]. In contrast, the fearful (high avoidance, high anxiety)indicates a high level of insecure attachment. The fearful has a negative model of self and others, characterized by having feelings of worthlessnes, distrust and rejection of others [

9], leading to negative evaluations of both self and others and tendency to hold negative attitudes towards humanity. Studies on dehumanization experiences in interpersonal relationships[

21]or attachment relationships[

31] found that dehumanization is usually associated with avoidant (e.g., numbness, sadness) and other negative emotions, as well as behaviors related to poor relationship quality[

4]. Therefore, Insecure attachment is more likely to be associated with high levels of dehumanization.

4.3. Relationship Between State Adult Attachment and Dehumanization

The results of the ANOVA showed that the main effects and interaction effects of group and attachment types on self-dehumanization and other-dehumanization were significant. Simple effect analysis indicated that, under both priming conditions, avoidance scored higher in self-dehumanization and other-dehumanization than security and anxiety. For secure priming group, anxiety scored lower in other-dehumanization compared to the secure group, whereas the differences under other conditions were not significant. Regression analysis revealed that security and avoidance significantly predicted dehumanization, while anxiety did not.

These findings partially corroborate previous studies. For example, Mikulincer et al. [

17]found that when primed with the names of secure attachment figures, participants reported more helping behaviors. The reason is the feelings of support and care in social relationships can evoke a sense of interpersonal security. The care and support for others reduce the differences between in-groups and out-groups, enhancing the welfare of all humanity and reducing dehumanization. Secure attachment priming can trigger more positive, open, and flexible information processing, making individuals active in interpersonal interactions, willing to maintain stable relationships with others, and inclined to adopt positive interpersonal strategies. This reduces egocentrism, increases prosocial behavior, and decreases aggression, prejudice, and discrimination [

32].

In contrast, the typical features of avoidance are indifference and rejection. Individuals of avoidance often dealing with interpersonal problems through blame, coldness, and withdrawal, devaluing or minimizing the importance of relationships[

17]. Such behavior can result in prejudice, negation, thus, higher levels of dehumanization. More importantly, anxiety under secure priming resulted in lower other-dehumanization compared to security. The possible explanation might be individuals with anxiety hold a positive view of others, which is enhanced under secure priming, leading to lower levels of other-dehumanization. However, regression analysis showed that anxiety did not significantly predict dehumanization. The reasons might be the inherent contradictions and inconsistencies of anxiety. On one hand, desire for interpersonal connection exists, but on the other hand, an exaggeration of potential negative outcomes could lead to negative responses, such as anger, hurt, and over-reflection[

33], as a result, can not significantly predicting dehumanization.

4.4. Limitations and Further Directions

Although this study was the first to discover the relationship between adult attachment and dehumanization, and validated the predictive effect of adult attachment on dehumanization, the underlying mechanisms still need to be further explored in the future. The path through which adult attachment affects dehumanization is crucial for preventing and intervening in dehumanization from an attachment perspective; Of course, it would be better to explore the vertical relationship between attachment and dehumanization, from the perspective of attachment development and changes in an individual’s childhood to adulthood. Exploring the vertical relationship between attachment and dehumanization in an individual’s life should lead to a more systematic and macroscopic conclusion.

5. Conclusion

This study explored the relationship between adult attachment and dehumanization from the perspective of trait attachment and state attachment. Study 1 conducted a latent profile analysis of trait adult attachment, validating the four-type attachment theory and demonstrating the differential impact of the four attachment types on dehumanization. Study 2 investigated the relationship between state adult attachment and dehumanization, revealing the differences in the impact of the three attachment types on dehumanization under secure and neutral priming conditions, as well as the positive predictive effects of attachment security and attachment avoidance on dehumanization.

Nowadays, new forms of dehumanization phenomena have appeared, such as bullying, cyber violence, and local conflicts.Therefore dehumanization deserves more attention in localized research in China. This study related attachment theory with dehumanization, validating the relationship between adult attachment and dehumanization, and highlighting the functions of attachment in social development. The findings provided theoretical and practical pathways for establishing relevant development and education mechanisms to resolve current social conflicts and contradictions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.; methodology, M.G. and B.X.; software, M.G. and B.X.; validation, M.G. and B.X.; formal analysis, M.G. and B.X.; investigation, M.G., H.W. and B.X.; resources, M.G. and H.W.; data curation, M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G., B.X. and H.W.; writing—review and editing, M.G., B.X., H.W and Z.Y.; supervision, Q.S.; project administration, Q.S.; funding acquisition, Q.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by 2022 Anhui Province Philosophy and Social Science Planning Key Project Topic(Project No: AHSKZ2022D20)

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were undertaken in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants in this study are gratefully acknowledged. We would also like to acknowledge other students in the research group for their help in the process of this research.

Data Availability Statement

The research data will be available upon request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

All participants in this study are gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Haslam, N. Dehumanization: An Integrative Review. personality and Social psychology Review. 2006, 10, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, N. Dehumanization and the lack of social connection. Current Opinion in psychology. 2022, 43, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, N. The social psychology of dehumanization. 2021.

- Kteily, N.S.; Landry, A.p. Dehumanization: trends, insights, and challenges. Trends in cognitive sciences 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss.Vol. I. Attachment.1982.

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, p.R. An attachment perspective on psychopathology. World psychiatry. 2012, 11, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, C.; Shaver, p. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of personality Journal of personality and Social psychology. 1987, 52, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; et al. patterns of Attachment: A psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 1978, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, K.; Horowitz, L. M. A ttachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. Journal of personality & Social psychology. 1991, 61, 226–244. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, K.A.; Clan, C.L.; Shaver, p.R. Self report measurement of adult attachment An integrative overview. In Attachment theory and close relationships; Smpson, J.A., Rholes, W.S., Eds.; The Guilfon press: New York, 1998; pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Xie, J.; Wang, H. principles, Steps and procedures of potential Category Modeling. Journal of East China Normal University(Educational Sciences) 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam, N.; Bain p Douge, L.; Lee, M.; Bastian, B. More human than you: attributing humanness to self and others. Journal of personality & Social psychology. 2005, 89, 937–950. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, T.A.; Robison, M.; Joiner, T.E. Dehumanization and mental health: clinical implications and future directions. Behavioral Sciences. 2023, 50, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z. Nonhuman treatment reduces helping others: self-dehumanization as a mechanism. Frontiers in psychology. 2024, 15, 1352991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillath, O.; Hart, J.; Noftle, E.E.; Stockdale, G.D. Development and validation of a state adult attachment measure (SAAM). Journal of Research in personality. 2009, 43, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, J.; Sargent, E. The meaning of life (events) predicts change in attachment security. personality and Social psychology Bulletin. 2003, 29, 1383–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, p.R. Attachment security, compassion,and altruism. Current Directions in psychological Science. 2005, 14, 4–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Gillath, O.; Halevy, V.; Avihou, N.; Avidan, S.; Eshkoli, N. Attachment theory and rections to others’ needs: Evidence that activation of the sense of attachment security promotes empathic responses. Journal of personality and Social psychology. 2001, 81, 1205–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, K.A.; Clan, C.L.; Shaver, p.R. Self report measurement of adult attachment An integrative overview. In Attachment theory and close relationships; Smpson, J.A., Rholes, W.S., Eds.; The Guilfon press: New York, 1998; pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Kazuo, K. Measurement of adult attachment: Chinese version of the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR). Acta psychologica Sinica 2006, 399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian, B.; Jetten, J.; Radke, H.R. Cyberdehumanization: Violent video game play diminishes our humanity. Journal of Experimental Social psychology. 2012, 48, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ma, B.; Ma, T.; Zhang, F. Effects of pro-social video games on players’ humanization perception level. psychological Development and Education. 2014, 30, 561–569. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, S.L.; Moore, E.W.G.; Hull, D.M. Finding Latent Groups in Observed Data: A Primer on Latent Profile Analysis in Mplus for Applied Researchers. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2020, 44, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sun, Y.; Tuo, R.; Liu, J. The effect of secure attachment on interpersonal trust: the moderating effect of attachment anxiety. Acta psychologica Sinica. 2016, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Li, p.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, M.; Li, X.; Tian, Z.; Omri, G. Chinese version of the Status Adult Attachment Scale in Chinese university students in China. Chinese Journal of Clinical psychology. 2012, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chavis, J.; Kisley, A. M . Adult attachment and motivated attention to social images: Attachment-based differences in event-related brain potentials to emotional images. Journal of Research in personality 2012, 46, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, O.; Raz, S. Adult attachment and emotional processing biases: a nevent-related potentials (erps) study. Biological psychology. 2012, 91, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilber, A.; Goldstein, A.; Mikulincer, M. Adult attachment orientations and the processing of emotional pictures-ERp correlates. personality and Individual Differences. 2007, 43, 1898–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ma, L.; Li, F. The mediating role of college students’ interpersonal trust between adult attachment and interpersonal distress. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2016, 864–868. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Holly, C. A study of the relationship between social anxiety and adult attachment type in college students. China Journal of Health psychology. 2009, 954–957. [Google Scholar]

- pizzirani, B.; Karantzas, G. C.; Roisman, G. I.; et al. Early Childhood Antecedents of Dehumanization perpetration in Adult Romantic Relationships. Social psychological and personality Science. 2020, 12, 194855062097489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C. . Attachment initiation and its effects. Advances in psychological Science. 2020, 28, 1539–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, A.; Patterson, M.M.; Wang, H. Attachment, empathy, emotion regulation, and subjective well-being in young women. Journal of Applied Developmental psychology 2023, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).