Preprint

Article

Digital Communication: From School to Society

Altmetrics

Downloads

69

Views

18

Comments

0

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

20 June 2024

Posted:

20 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

In this work we offer a broad overview of the combination of digital communication, education and society and show the link between learning with digital and awakening to the future. We trace the effects of digital communication acquired during postgraduate training at the Universidade Aberta of Portugal by professionals from African Portuguese-speaking countries. From a methodological point of view, the study identifies former postgraduate students at the Universidade Aberta (Public University of Higher Education) over the last five years who were given a comprehensive questionnaire aimed at finding out how the training they underwent contributed to gauging their current levels of application of digital communication in their current profession. We found that digital communication in learning and its diversification acts as a lever for personal and professional development following the acquisition of academic knowledge.

Keywords:

Subject: Social Sciences - Education

1. Introduction

The Our society is currently a hybrid society, where we move around without a clear distinction between the digital world and the real world. Faced with the speed of information, true or false, the boundaries are blurred, and it is difficult to determine which knowledge prevails over the other.

In the last decade, issues related to digital communication have become increasingly prevalent in the different spheres of our society. If we think of digital communication as the set of norms related to appropriate and responsible behaviour in the use of technologies, digital citizenship, an important issue in the digital age, and the educational sphere are no exception. We currently live in a world that has been transformed by digital technologies, allowing effortless connection through social networks and access to vast amounts of information. The ability to deconstruct this hyper-rich information and get involved effectively and responsibly poses a few new challenges as we seek to prepare citizens to exercise their rights and participate effectively in community affairs.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Digital Technology as a Vector for Transforming Education

The professional competences of teachers defined at European level by the Common European Principles for the Competences and Qualifications of Teachers (2010) identify three essential competences for teachers, including the ability to

- work with others (students and colleagues);

- work with and in society;

- work using their knowledge, whether subject-specific or not [1].

More generally, we believe that we need to solve the fundamental problems facing our education system - confirmed by international assessments (PISA) - in terms of educational inequalities in terms of access to technology and digital equipment, digital literacy, and critical thinking. Of course, ‘digital’ alone cannot solve all these crucial problems for our societies, but we believe that the study of digital communication in education can help provide some answers, on the one hand through training in digital communication and, on the other hand, through research and new uses of digital that can bring additional benefits, pedagogical value, and active and responsible participation in society.

Digital communication can be used to mediate the educational relationship, but also to mediate training content [2] and learning activities. Digital communication does not guarantee added educational value or educational innovation. Although digital can provide a new medium, the teaching relationship and pedagogical practices are not always innovative. For example, the principles of the inverted classroom or learning through games, already present in analogue form, are not an innovation from the point of view of the pedagogical relationship but take on a new form with the support of digital [3]. The increase, modification, and redefinition of practices using digital technology suggests the ability to support the teacher and student by personalizing learning. Teaching and learning processes are complex, and to understand the changes introduced using digital, we need to consider not only the task itself, but also the subject-specific knowledge involved in the task. This education in the fundamentals of digital communication is a prerequisite for the enlightened use of digital.

2.2. An Invitation to Critical Thinking

Firstly, the topic of ‘digital communication and education’ is far from exhausted, not least because the context is constantly evolving. More specifically, this evolution is the result of three factors, both intrinsic and extrinsic:

- 1)

- the development of new pedagogical approaches centred on the student. See, for example [4], who puts the last decade of work on digital education into perspective and notes that the emphasis has been placed more on the student than on the technology; the psychological and emotional effects of mediatization of learning through technology, as well as ethical and safety aspects, must be considered when integrating communication and digital education.

- 2)

- changes in teaching practices caused, or not, by technological innovations and the question of their implementation in society far beyond the field of training.

- 3)

- social and political expectations for a learning society, reflected in successive parliamentary reports [5]. These reports address the issue of the appropriation of technological innovations, their implementation, and the evaluation of their pedagogical added value.

2.3. A Multidisciplinary Issue

It's important to approach this subject from a multidisciplinary perspective and not just in terms of hardware and/or software, as has often been and still is the case. We believe it is essential to also consider other areas, educational or digital sciences, cognitive sciences and neurosciences that can shed light on digital communication, considering the diversity of contexts, tasks, and inter-individual differences. On the other hand, as with any tool, the use of digital equipment can present risks and negative effects that must be considered. For example, the proliferation of digital tools can lead to mental overload, or personalization can lead to unethical behaviour or disrespect for the privacy of students or teachers.

2.4. Digital Citizenship

Digital citizenship refers to the ability to interact positively, critically, and competently with the digital environment, using effective digital communication and creative skills to practice forms of social participation that respect human rights and dignity through the responsible use of technology.

We can try to define digital citizenship as the effective and positive use of digital technologies (creating, working, sharing, socializing, researching, playing, communicating and learning), active and responsible participation (values, skills, attitudes, knowledge) in communities (local, national, global) at all levels (political, economic, educational, social, cultural and intercultural), involvement in a dual process of lifelong learning (in formal, informal and non-formal contexts) and the ongoing defence of human dignity.

This approach to digital citizenship is based on the Competences for a Culture of Democracy developed by the Council of Europe [6], which reminds us that the competences needed by any citizen to be able to participate effectively in a culture of democracy are not acquired automatically but must be learnt and practiced. Education therefore has a key role to play in helping people acquire the skills and competences they need to become active citizens.

Digital communication is constantly evolving and affects many aspects of contemporary society: social relationships, economic life, the environment, democratic practice, the cultural industry, personal life, etc. The school helps students to understand the implications of digital technologies in the world around them, particularly in terms of creating and transmitting new knowledge, developing their technical, reflective, and critical thinking skills. In this way, it equips them with a digital culture. These skills and the behaviours that result from them are an essential link in the students' educational journey, but also one of the keys to their professional and social integration. In the service of digital citizenship, digital education contributes to education for citizenship.

2.4. Education for Digital Citizenship

Education for digital citizenship refers to the empowerment of children through education or the acquisition of skills to learn and actively participate in the digital society. It is also linked to the knowledge, skills and understanding necessary for users to exercise and defend their democratic rights and responsibilities online and to promote and protect human rights, democracy, and the rule of law in cyberspace. At its simplest level, digital citizenship education seeks to ensure that those who are not ‘digital natives’ or who do not have the opportunity to become ‘digital citizens’ are not marginalized in future societies.

Digital citizenship represents a new dimension of citizenship education, specifically aimed at teaching students how to work, live, and share positively in digital environments.

2.5. Technological and Social Change

As Gilbert Simondon (1958) analysed, since the dawn of humanity, mankind has continually invented technologies to manufacture technical tools to improve the conditions of its existence. Some of these technologies cause major changes in the human societies from which they originate, requiring the men and women of these societies to learn new skills if they want to benefit from them and not be alienated from them. A profound transformation has taken place in our societies since the emergence of information technology and the ‘digital’ technologies that stem from it, and it raises questions about the paradigm shifts in learning with and through digital communication.

Of course, whatever the transformations brought about by technological inventions and uses, there are invariants in the way humans learn. Homo sapiens is extremely good at learning. This ability is collective and not just individual. Its mimetic capacity ensures that it learns continuously, even ‘effortlessly’, by interacting with its everyday environment. However, as André Tricot (2017) observes in addition to this primary knowledge, other types of secondary knowledge need to be intentionally taught so that they can be acquired by students. The role of the school is precisely to provide this unnatural education, which cannot be taken for granted.

Knowledge and learning processes are the school's responsibility, but not the only one. The influence of the student's family and social environment plays an important role, especially when it comes to ‘knowing how to be’ and ‘being’.

Many factors, both individual and collective, organizational, and socio-cultural, need to be considered in the didactics / pedagogical work carried out by the various educational actors when developing teaching and learning situations.

An individual's behaviour can be analysed from different perspectives, biological, mental and social. We need to design educational situations that can foster self-confidence and motivation, enabling engagement. Teachers must take these different aspects into account when developing their activity [3]. Given the fundamental importance of the role of teachers in designing and orchestrating learning activities, the training of these teaching and learning professionals will have to be approached in connection with digital communication and the uses of digital to support teaching and learning processes.

3. Materials and Methods

In contexts where access to the internet is limited, or technological devices do not yet exist for everyone, it makes sense to study the ways in which digital communication processes can be facilitated through the actions of those who have been given a privileged opportunity through scientific training.

The aim of this work is to map the effects of digital communication acquired during postgraduate training at the Universidade Aberta (UAb) by professionals from Portuguese-speaking African countries (PALOP – Países Africanos de Língua Oficial Portuguesa) and to characterize the levels of current application of this digital communication by former students in their work contexts.

From a methodological point of view, this is a quantitative, exploratory study that aims to identify regularities and trends that characterize the digital communication developed and to assess its effects on the current professional activities of former students from the PALOP who attended a postgraduate course at UAb of Portugal, in the last five years. The choice of these recipients is due both to the borderless vocation, within the Lusophone space (the Lusophone Space is made up of territories where Portuguese is an official language), of the training offered by the Universidade Aberta (Open University), thanks to its virtual learning model, and to the fact that these professionals work in contexts where access to technological educational resources is more difficult.

To operationalize this aim, a questionnaire was drawn up to identify the contribution made by the training to the digital communication acquired by the former students who are the subject of this study. The questionnaire was organized into three distinct parts. The first part was aimed at characterizing the respondents in terms of age, gender, profession, and training attended at university education. The second block of the questionnaire was designed to assess the contribution of the training carried out at the University to the development of the respondents' digital skills. The third part of the questionnaire aimed to assess the effects of the digital training developed during the training at Universidade Aberta (on the respondents' current professional activity. Within these effects, we were interested in knowing the degree of applicability of digital communication skills; the digital tools used; the degree of usefulness of these digital tools in their current professional activity; the most important activities they carry out in their professional activity that use digital; and the ethical and security concerns they are aware of. In this paper, we will focus solely in the last part, on the contribution of the training carried out at the Open University of Portugal to the development of digital communication skills in professional life.

To map out the study's population and sample, all Universidade Aberta students and former students who met the two initial conditions were identified: being from the PALOP countries and having attended a postgraduate course. This process made it possible to identify 130 students who were sent a request to take part in the study. Of the 130 students who made up the population, 61 agreed to answer the questionnaire (47 per cent).

The questionnaire was administered digitally on the GOOGLE forms platform between 15 November and 15 December 2023.

Descriptive analyses were made comparing the aspects that identified the training and the corresponding aspects that characterize the professional activity of the respondents.

As mentioned, access to the former Universidade Aberta students who made up the population was provided by the University itself, so that these people could be contacted via email. However, the questionnaire they were asked to fill in did not identify them in any way, and the questionnaire itself explained the aims of the study and other ethical safeguards, which is how informed consent was requested.

4. Results

The 62 respondents, 20 women and 42 men, are on average 43 years old (45 women and 43 men) and come from 4 of the countries in scope: Cape Verde (18), Angola (17) São Tomé (2) and Mozambique (25). Of the 62, only 4 do not work in their countries of origin, but in other Portuguese-speaking countries, and one in a different country. The courses they attended at the Open University of Portugal are some of the most diverse 2nd and 3rd cycle courses offered by the university, although the courses in Mathematical Statistics and Computing; Management/MBA; Portuguese Language Studies and Pedagogical Supervision were the ones with the highest number of respondents.

Half of the respondents are currently teaching, mainly in higher education, but also in other levels of education, and the other half of the sample is divided between other professions and other positions, namely management positions (2), research positions (3), managers (5) and senior technicians in various fields (19).

On average, the time spent working (total weekly working hours) is 33 hours, with men reporting a higher number of weekly working hours (34 hours) while women report 29 hours. On the other hand, the time they spend on professional activities only possible with digital devices (aka computers) is 23 hours on average, 24 hours for men and 21 hours for women.

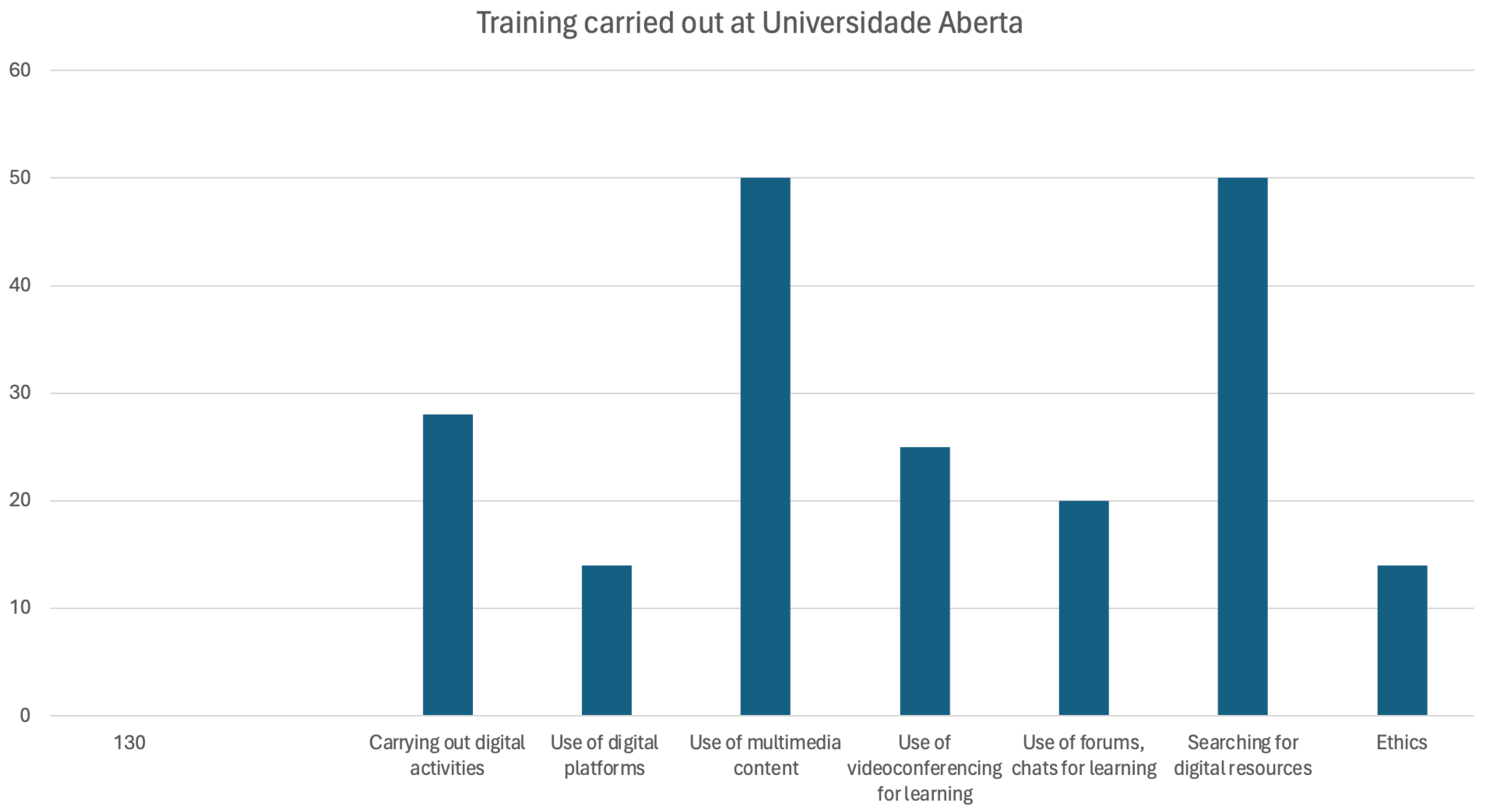

During the course at Universidade Aberta (Figure 1), the former students considered the activities they carried out using digital media to be between important and very important, which consisted of searching for resources; carrying out the activities requested; processing the information collected; working in groups with colleagues; presenting work and reorganizing work after receiving feedback from the teacher. Except for this last item, which does not apply to the professional context, we can see that in the professional activity the former students equally value the possibility of carrying out professional work, performing the same type of tasks. This is a case of recognizing the similarity of the tasks, if not the preparation and training that attending the course has given them in reorganizing their professional tasks.

About the importance of ethical issues, the training carried out at the UAb served as a starting point for raising awareness of this importance, since the levels obtained in the appreciation of these issues in relation to the course were systematically slightly less important when compared to the current importance felt in a professional context.

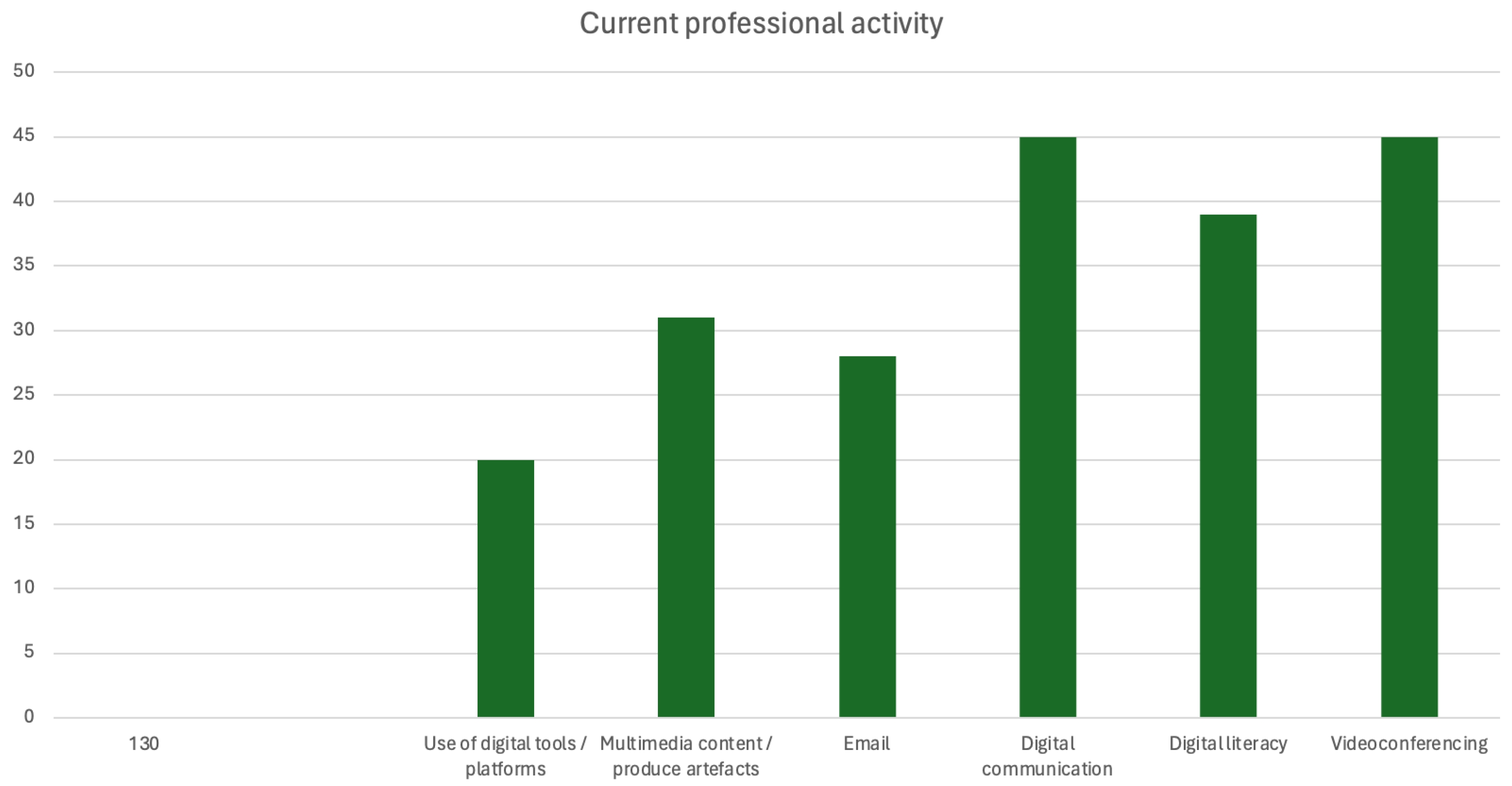

From the point of view of applicability in current professional life, we can see from the responses collected a similar valuation, almost always between important and very important. Only e-mail is a communication tool that is perhaps more important in the current professional life of most former students.

In today's professional life (Figure 2), the digital tools mentioned seem to be of greater importance to the respondents, in absolute terms and when compared to their importance in relation to learning. Even educational videos and games and scientific simulation tools are of greater relative importance in terms of their use in the respondents' professional context.

In Figure 2, we show the data on the dimensions of digital communication in relation to the professional activities carried out by the respondents and we see a progressive decline in the importance/or use of digital in professional contexts, depending on whether it is communication/collaboration, working on platforms or using computer applications, or producing resources or products. We also found significant differences between digital literacy and its access and the two dimensions of working and producing digital artefacts. There are also significant differences between this last dimension of digital competences and the dimension of communication and collaboration in terms of use and importance for the respondents' professional activity. Finally, it should be noted that awareness of ethical and security issues are important aspects of self-described digital competence.

From this comparative assessment of the aspects that were present in the training attended at Universidade Aberta and the digitally modelled activities that the former students are currently engaged in, there is a tendency to deepen and give greater importance to both communication skills and the use of digital tools, as well as the increasingly digital dimension that characterizes the professional activities that the respondents are engaged in. It therefore makes sense to provisionally conclude that the contribution of the training provided to the digital skills acquired by the former students in this study may have been to sensitize, initiate or train them.

5. Conclusions

It is now time to look at the objectives of this work and see how they have been met.

Mapping the effects of digital communication acquired during postgraduate training at the Universidade Aberta of Portugal by professionals from the African Portuguese-speaking countries (PALOP) made it possible to see the different levels of training obtained by former students during their courses. What was also found was that the general dimension of digital literacy and the dimension of communication and collaboration were the ones with the highest levels of agreement among the respondents regarding the importance that the training they received gave them.

The study also showed that in their current professional lives (at the time of answering this questionnaire) almost all the digital tools mentioned are of greater importance to the respondents, in absolute terms, when compared to their importance in relation to the learning carried out during the course attended at the university education. As this greater importance refers to current use, it is also inferred how important the training provided at the Universidade Aberta was in enabling students to use these tools, as well as their relevance to the performance of the former students' professional activities. There is also evidence of the alignment between the digital tools mobilized by the UAb training offer and their usability and suitability for professional contexts.

Another important conclusion, due to its wide-ranging significance, is that which relates the time dedicated to digital activities within the profession to the importance attributed in general to the tasks in which digital competence is operationalized. In fact, like [7], it's not just a question of using technologies to produce work, but also of reflecting on the impact of this use in reconfiguring the way we think.

The results presented have limitations that the study could not overcome it was not possible to accurately assess the effect of the pandemic, nor was it possible to analyse in greater detail the weight of personal variables on the results obtained. These limitations result from the size and non-random nature of the sample.

However, despite these limitations, the study presented here is important for understanding the power of the use of digital communication and its influence on shaping the actions of former Universidade Aberta of Portugal postgraduate students, which we hope to be able to further develop.

References

- Nobre, A. Multimedia technologies and online task-based foreign language teaching-learning. Tuning Journal for Higher Education 2018, Vol 5, No 2, From innovative experiences to wider visions in higher education. [CrossRef]

- Peraya, D. Un regard critique sur les concepts de médiatisation et médiation : nouvelles pratiques, nouvelle modélisation, 2008, Les Enjeux de l’information et de la communication.

- Tricot, A. L’innovation pédagogique – Mythes et réalité, 2017, Édition Retz.

- Lai, K. W. The Learner and the Learning Process: Research and Practice in Technology -Enhanced Learning, Second Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education, 2018, pp 127-142.

- Taddei, F.; Becchetti-Bizot, C.; Houzel, G. Un plan pour co-construire une société apprenante, 2018. https://cri-paris.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Un-plan-pour-co-contruire-une- societe-apprenante.pdf.

- Council of Europe, Handbook of Digital Citizenship Education: Being online, Well-being online, Rights Online, 2019, Council of Europe Publishing.

- Nobre, A. Walking Side by Side: Digital Humanities and Teaching-Learning of Foreign Languages. Handbook of Rsearch on Learning in Language Classrooms Through ICT-Based Digital Technology, 2023, pp 17. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Dimensions of Digital Communication in academic training.

Figure 2.

Dimensions of Digital Communication in professional life.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated