1. Introduction

Contemporary narratives on the issue of the rural identity of a place have generally shown that this question remains an important one when it comes to the spatial analysis of these communities' construction, their reproduction in time and space, and the related aspect of their representations as seen in people’s perceptions in response to the key question of where they belong, ranging from social and economic perspectives to cultural and political ones. Furthermore, there is scope for the territorial identity of a rural place to be successfully used as an instrument in local decision-making by the structures of regional and national government with a view to fostering social and economic development, since territorial identity representations have relevance for local communities and for social and cultural aspects of their sense of belonging [

1].

Rural and regional identity represent the best analytical accounts for understanding place attachment and the sense of belonging [

2], the cultural distinctives and standard features of a place [

3], and the spatial representation of

us and

the other as expressions of power geometries on different spatial scales [

4]. Regional identity are social processes with multiple dimensions for the construction of rural space, for the complex processes of the cultural identity affirmation of a place, and for its representations in everything from discourses to practices. “The idea of regional identity has been implicit in geography for a long time, since traditional approaches to regions and regionalism often celebrated the primordial nature of regions, accentuating their ‘personality’ and the harmony/unity between a region and its inhabitants” [

5]. In this context, it is widely argued that regional identity has become an important category in the ‘Europe of the regions’, and one that is often taken as self-evident in the relations between a group of people and a bounded region [

5]. Narratives of regional identity are based on such specific elements as “the ideas on nature, landscape, the built environment, the culture/ethnicity, dialects, economic success/recession, periphery/center relations, marginalization, stereotypic images of a people/community, both of ‘us’ and ‘them’, actual/invented histories, utopias and diverging arguments on the identification of people” [

5]. Rural identity refers to a thing’s property of preserving its fundamental characteristics over a long period, while 'territory' refers to the area of land delimited by the boundaries of a state or administrative unit and subject to the sovereignty of that state. While many studies have covered these general aspects on a variety of spatial scales, work on defining the cultural identity of a place or region, particularly in rural areas, is still needed, especially as regards communities’ and people’s connection with/affection for specific aspects of a place (natural features, landscape, local cultures), as argued by Paasi [

5]. Communities and people construct significant affection towards various natural and cultural features of the places where they live, generating places and spaces of unicity and authenticity which require to be understood largely through the lens of local and regional identity, through the cultural representation of the places where the people concerned live.

In line with these arguments, this paper explores local rural identity and its relationship to broader regional identity, more specifically the question of

us and

the other, as exemplified by territorial rural identity representation in a particular part of Romania that is divided by the river Mureș. Our selected case study sets out to portray the role of water/the river and its related cultures in the social and cultural construction of this region and of its specific rural places, arguing that the culture of water [

6,

7]. and the local cultures closely connected to the natural features of a place are responsible for the construction of the local and regional identity of, and in, specific places and regions. The Mureș is one of Romania’s major rivers and the largest tributary of the river Tisa, into which it flows after crossing the border into Hungary. With its main course of 789 km (of which 761 km are in Romania), it is one of the most significant flowing waters in the Carpathian basin. Furthermore, the river has been a boundary throughout history, serving as a border between various countries and even empires (Kingdom of Hungary, Ottoman Empire, Habsburg Empire). It is a natural element functioning both as a boundary and as a highway linking different cultures, communities, and people. Of the countless rural settlements lying along this river, Vărădia de Mureș and Birchiș represent two small, interesting communities with specific rural identities. Vărădia de Mureș is located on the northern side of the Mureș and is part of the historical region of Crișana, while Birchiș lies to the south of the Mureș and is part of the historical region of Banat.

The present study aims to explore, through the lenses of quantitative and qualitative research, the sense of their rural identity felt by the inhabitants of these two villages. We are also interested in how local inhabitants relate to the river as a symbol of opportunity, limit/boundary, and danger/risk issues. Our research questions are as follows:

Besides contributing to existing international studies on rural identity [

8,

9] and its connection to the cultural role of water [

10,

11,

12,

13] and to studies on regional belonging [

5], this study complements recent debates in Romanian social science literature on the rural and regional identity of people belonging to the Banat and Crișana regions [

14] and the role of spatial vicinity and the strong regional identity of local Romanian Banat people [

15,

16] by shedding light on the role of the river Mureș in dividing, in cultural terms, the two regions of Banat and Crișana.

We have devoted the next section to a theoretical approach in order to make a link between our selected case-studies and study area and international theoretical models regarding regional identities in rural areas. This will help us provide a critical and objective account of questions of local rural identity in cases in which it gravitates to a specific natural feature that over time generates specific cultures and particular communities with unique cultural identities.

2. Theoretical Background

Regardless of their sizes, locations, and cultural features, all communities have the power to construct their own specific identities. These are closely connected to the features of the local natural environment, to the cultural and historical background. This is a means through which communities define their individual cultures as specific attributes in a world that is increasingly tending towards a shared universality. Regional identity appears as a social process [

17] and is “…an interpretation of the process through which a region becomes institutionalized, a process consisting of the production of territorial boundaries, symbolism, and institutions. This process concomitantly gives rise to, and is conditioned by, the discourses/practices/rituals that draw on boundaries, symbols and institutional practices” and involves two intertwined backgrounds: a cultural-historical one and a political-economic context [

5,

18].

Numerous writers have studied regional identity from the perspective of the geographic construction of spaces and have argued for the significance of local identities and the importance of this process in our contemporary world [

19,

20,

21,

22]. As different to national belonging and nationalist identities [

23], multiple issues of regional identity have been discussed, including regarding regions and places, the situation of bounded places in a mobile world in which identity is closely connected to the construction and deconstruction of spaces, and in the context of regional reconstruction and devolution [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. It is widely acknowledged that regions represent institutionalized places and spaces, with their emergence and development being framed by political and economic factors that are responsible for the creation of their regional identity [

29], which means that the issue of identity – connected to regional planning, regional resurgence and the construction of regional identity from the viewpoint of power and politics – is an important aspect which needs to be taken into consideration in the representation of the territorial identity of a place or region [

30,

31]. These approaches must be taken into account in any geographical analysis of regional identity, most especially against the contemporary background of social and economic development, in which collective identity and community identity have to be understood as vectors of social and economic transformations taking place in reaction to current challenges facing our world [

5]. Local models of community development represent significant actions that aim to construct local identity in the various contexts of regional economic development. Under the new model of regionalization, in which local policies and decisions also have a part to play, both the complex of factors that combine in the regional identity construction of a place on the one hand, and economic development and local planning on the other, contribute to the identity individualization of a place or region, whether we are thinking of local development based on local resources and economic practices or of that resulting from new strategies for regional economic progress directed by Romanian and international policies. With regard to the issue of local territorial identities, the economic development of places and regions continues to be something that needs to be studied when we seek to understand the place of identity construction in contemporary geographical analysis. Such approaches turn regions and places into perceptual regions, into places in which new kinds of identities can be imagined [

32,

33]. Local economic development and regional planning are important features of a region’s identity construction that must be borne in mind in the context of the construction of the local identities of places and regions, since they frame both people’s ordinary way of life and the cultural landscape of communities [

34]. They must be understood if we are to grasp the chief mechanisms that define the cultural traits and values of a given area. In terms of the individual specificities of a landscape, multiple types of cultural landscape have come into existence [

35], all of them demonstrating the main cultural activities, practices and actions which have built the cultural identity of the people, represented over time and space in many different ways [

32,

36]. Furthermore, against this background, it is these social, cultural, economic, and political traits that operate as the main vectors which through the intermediary of local cultures and resources construct and establish the local identity of a community [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Rural communities are especially important to decode, for it is the rural space that best preserves its cultural features and values, its local ways of life and its cultural landscapes, all on the foundation of its people, resources and activities and of its traditions and inherited cultures [

9,

41].

In the construction of rural identity, the place itself matters, as well as all the actions and initiatives which ensure the social construction of a place [

8]. In this context, the effects of rural identity are evident in the cultural landscapes of communities [

42], because their cultural traits and all their social and economic practices are intended to provide particular landscape aesthetics and specific functionalities reflected in the local identity of rural communities [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. In rural development the marks of regional identity represent an important key to understanding how rural settlements have built their own cultural identity landscapes and how these are represented in current analyses, practices, and discourses. In the context of the development of rural communities, regional identity is shaped by local resources, by the modes of local production and construction of these places based on their inherited or borrowed cultural traits and practices as managed and administered via various types of local and regional governance, and by local community development policies [

49]. Looking at the whole ensemble of environmental resources, water represents a feature that has always both contributed to community formation and guaranteed specific cultural identities through the individual modes of the local production and reproduction of a community. Water is perhaps the most important geographical attribute framing the spatiality, functionality and symbolism of a place or a region, especially when we are speaking about traditional ways of life in different rural spaces. The local and regional significance and identity of a place are ensured by the presence of water and by all the opportunities it provides for people and communities [

10,

11,

12,

50]. Both a geographical feature that can divide places and spaces and one which connects people, cultures and societies, water and its related cultural and political identities represent the main resource that determines and directs communities by providing key pathways for the local and socio-economic development that frames specific cultural landscapes and particular cultural identities [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55].

Human settlements along riversides, especially in rural areas, have been common throughout history as a consequence of people's need to access water for drinking, irrigation, fishing, transportation, and other economic practices and activities in their various forms. Rivers have also been seen as major sources of food and building materials. Some of the world's earliest human settlements, such as those in Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt, and the Indus Valley, developed in areas near rivers because these provided fertile soil and a constant source of fresh water [

56,

57]. However, human settlements beside rivers may be vulnerable to flooding or other natural disasters, which means that careful planning and proper resource management are required [

58].

A source of both opportunities and risks for the community, water has the potential to provide the premises for territorial identity construction, with people and communities always being strongly attached to the places where they live. Affective perspectives and performed practices combine to generate specific cultural landscapes. Territorial identities can impact people's behaviors and decisions, while at the same time they can also be an important factor in promoting various kinds of economic development, including, in some areas, tourism. Contemporary geographies of territorial identity investigate not only spatial areas and arrangements but also the reasons why people interact with their local environmental features and the ways in which they do so [

57].

The rural landscape has up until now been studied in many ways and from a range of perspectives, with the subject of rural areas’ representations of cultural identity being an interesting approach to gaining new understandings of their functionalities and landscapes and to gathering relevant data on the basis of which to design new forms of spatial governance aimed at maintaining and sustaining local cultural identities. In these cultural-identity construction contexts, case studies are widely recommended [

49,

59,

60] as a method of obtaining new data that advances academic knowledge regarding the construction of rural identity and which captures significant information about the way of life in the countryside, the ways in which people feel and perceive their relationship with the lived rural space, and the ways that its local territorial identity is represented in the collective memory of a rural place.

3. Study Area, Materials and Methods

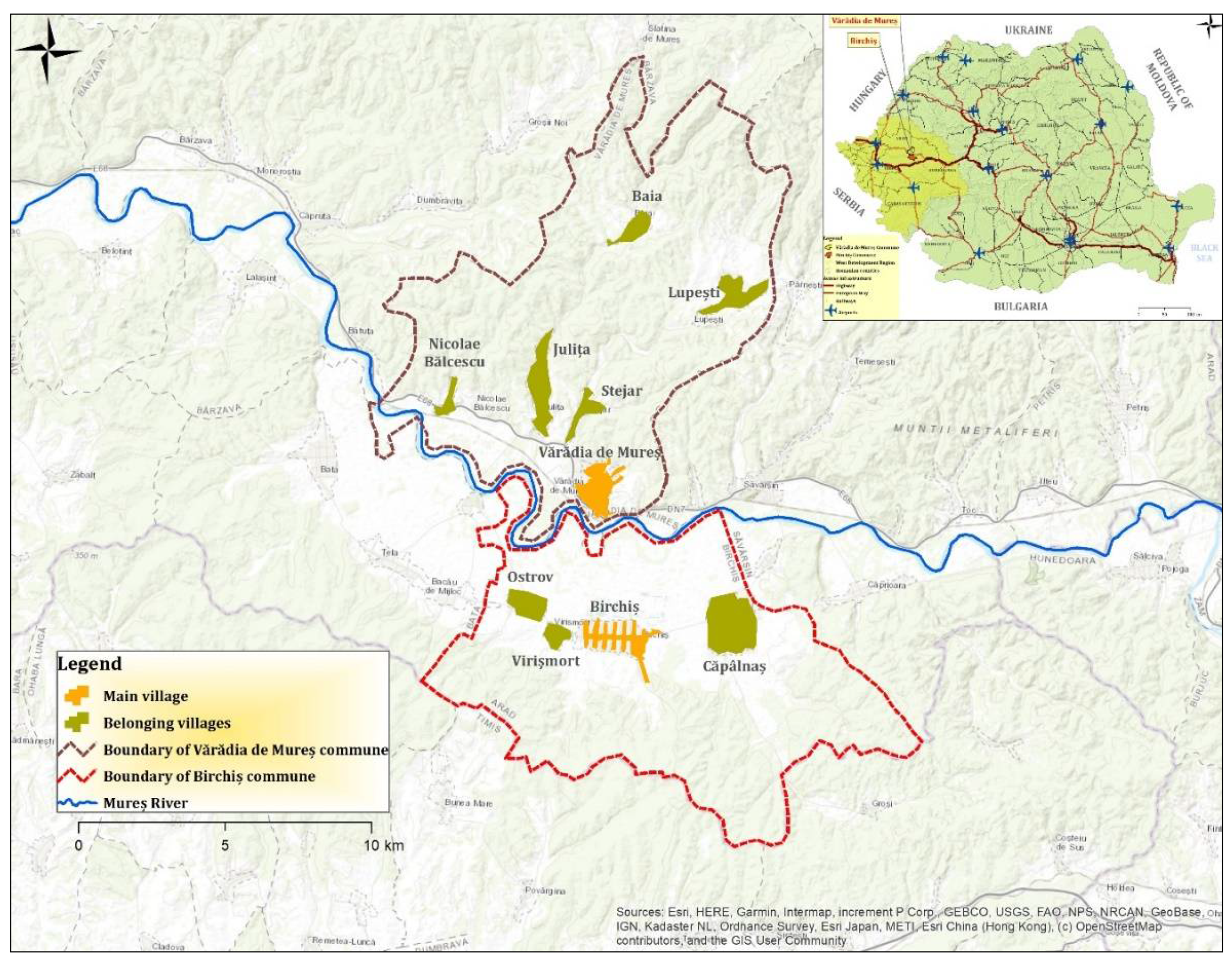

Vărădia de Mureș and Birchiș are situated in Western Romania, on the boundary between the historical regions of Banat and Crișana, marked by the river Mureș. Their location on this relatively closed corridor is reflected in their distance from towns and cities: 50 km from the nearest town (Lipova, with approximately 10 000 inhabitants [

61]), 80 km from the county town (Arad), and over 100 km from the main regional city, Timișoara. The most important nearby locality is Săvârșin, the main rural pole and the site of the Royal Castle, but even this has no more than 3 000 inhabitants (

Figure 1).

Vărădia de Mureș commune has 1587 inhabitants distributed among six small villages, while Birchis has 1773 inhabitants distributed between four small villages [

61]. Both communes have for over a century been on a trend of aging and demographic decline. The demographic peak was attained in both communes in 1910, when they had 4948 inhabitants. Even though Romania experienced significant demographic growth during the communist period [

62], in our study area the absence of cities and of investment in industry and services generated a massive emigration of young people, so that the area now ranks in the quartile of the oldest ones demographically in the country.

The Mureș valley is a connecting artery along which the plain extends into the mountain area in the form of depressional bays, which led in the past to the development of intensive agriculture. Connecting corridors were formed between settlements, strengthening the constant to-and-fro movement of population and of material and cultural goods in this area.

Our first

methodological step took the form of a literature review and of bibliographical documentation, focusing both on the concept of territorial identity and on the context of the study area. Next, in-field of participatory and empirical observation, as widely recommended, was a fruitful way of looking at the cultural landscapes of the communes being studied, providing important insights that helped us assess the cultural backgrounds of both rural settlements. The communes we took as case studies (a recommended method in academic research in this domain – see [

49] were carefully selected from an important region of Romania whose identity is shaped by the geographical and cultural significance of the river Mureș. Subsequently, we used the cartographic method (ArcGis 10.4 software) for a comparative analysis of the two villages in terms of spatial organization and territorial polarization, including in relation to the river Mureș, using data from the Romanian National Institute of Statistics and vectorized spatial data extracted from OpenStreetMap through the Geofabrik.de platform. The raster data is Copernicus Digital Elevation Model (GLO-30 DEM).

In order to round off the study by including a reflexive-explanatory dimension, in August 2023 we conducted 36 interviews with locals (20 from Vărădia de Mureș and 16 from Birchiș), applying 10 open questions that complemented those in the questionnaire (

Table 1). For this stage we set up face-to-face meetings with those willing to be interviewed, ensuring that everyone was at their ease during the discussions. All survey interviewees provided their consent and have been anonymized. The study was approved by the Scientific Council of University Research and Creation from West University of Timisoara (no. 33282).

The questions were about unique features of their home commune, the advantages that the Royal Castle in the neighboring commune of Săvârșin brings to the area, and how exactly they would describe the way their local government functioned. The interview also included questions about the future, whether interviewees were hoping to leave the commune in a few years’ time, and the importance of the river Mureș to the community. Inhabitants also explored the issue of which historical region they saw themselves as belonging to. The interviews were accurately transcribed, then thematically and chromatically coded following the methodology proposed by Bryman [

63]. Demographic data for the respondents is shown below (

Table 1).

4. Results: A Qualitative Analysis of Territorial Identity

Our qualitative analysis of the territorial identity points to four major frames: a broader perspective on the rural lived space; how the river Mures has brought a balance between benefits and risks at the local rural level; the imagery of regional belonging at the border between the Banat and Crișana regions; and the voice of local residents –their specific ideas, visions, beliefs and suggestions for local authorities.

4.1. A Broader Perspective on the Rural Lived Space

Local people are nostalgic when it comes to the past and the present. They always see differences between the lives they lived many years ago and the days they are enjoying now. Both periods have their pleasant and less pleasant sides. One of the memories mentioned by I2 originates from years ago: "we have local customs... we tried to do something cultural at least. It's a beautiful area, someone even came from the south of Romania, bought a house, and said we don't even realize what it means to have the hill, the Mureș valley, the road and the railway. Until then I hadn't even thought about it. We have everything... a picturesque place, foreigners like it." The same respondent also pointed out that the city no longer defines him, now, in his old age: "my dream in my youth was that I would go to the city, … but now I don't seem to find myself there anymore. Now everything is more complicated and tiring there, but I would like to go to shows, to the opera, to the theatre, I miss that so much here". He also remembers the way the commune was managed in the past, when, it seems, the locals were more concerned with the various aspects of running the place: "the administrative side of life is less good now than in the past, when everyone who worked for the Town Hall was interested in the proper running of the commune, following the lead given by the Mayor" (I16), and also the close link the people in Vărădia de Mureș had with the royal family's possessions: "Vărădia derives no benefit from the Castle, even though it is the neighbouring commune, there is a lack of interest in the airport where the king landed when he came here. He had a hangar and a house near the airport" (I16). Another interviewee told us that he worked in the construction industry in Spain for about 10 years, learned a lot from there, but has now returned home to be near his family and is currently working in the same field, but in Romania, close to his commune.

4.2. The Mureș: The Balance between Benefits and Risks at the Local Rural Level

By collating the responses of interviewees from the two communes in our study, we were able to identify two categories of considerations related to the river Mureș and two types of reaction that the locals had: positive ones that highlighted nostalgia, enthusiasm, and satisfaction about the river, and negative ones that betrayed fear, rejection, or even denial. The first set of factors observed, the favourable one, shows the advantages that the Mureș brings to the area: "it is as if we could not conceive of the place without the Mureș, it is part of our life. It's very beneficial for crops, all the maize fields near the Mureș have produced a harvest, the water probably keeps the ground moist" (I2), "the Mureș is a lifesaver, especially for those who have maize in the countryside, alongside the Mureș. It's also advantageous for fishing, children take a dip" (I3), "it's a great advantage for agriculture, for fishermen, it’s close by" (I7), "the Mureș can bring benefits for tourism, with recreational areas" (I19), "from the Mureș I took sand and gravel when I built my house 60 years ago. A benefit" (I23), "it is an opportunity for relaxation, fishing. It would have been nice for it to have been properly exploited" (I28).

Reviewing all these benefits enjoyed by the locals, one can certainly conclude that this river has its positive side, but with other interviewees their primary reaction is that the Mureș creates many problems and is dangerous. Statements such as "there is a risk of drowning" (I3), "many years ago the Mureș flooded up to the railway line at the edge of the village. When it bursts its banks, it destroys everything. No dykes have been built to reinforce it" (I10), "a danger. Many people have drowned there" (I16), "a peril responsible, in the past, for the deaths of several young people" (I21), "the Mureș comes up to our village" (I26), "disadvantage, due to flooding" (I27), and "disadvantage when the Mureș rises and floods our agricultural plots" (I32) all point to the fear that has taken root in the minds of some people. A double tragedy that took place years ago, the drowning of two members of the same Birchiș family, has left the bereaved survivor unwilling to hear or talk about anything related to this river: "I don't want to talk about the Mureș, it is a great danger. That's where my child drowned first and after a few years my husband did too. They both died...".

4.3. Imagery of Regional Belonging at the Border between the Banat and Crișana Regions

Whether from Crișana or Banat, whether from one side of the Mureș or the other, respondents had thoughts, stories, and tales to tell: "Tourists come to Săvârșin, they are curious, in a way this is how our area is known. When I'm away somewhere and someone asks me where I'm from, I always say I'm from Săvârșin, never from Vărădia, because my commune is not so well known. We are somehow proud of Săvârșin and people immediately know what we are talking about" (I2). These sentences exemplify the respondent's belonging to the area where he lives and works. When he is outside his commune, he chooses to mention Săvârșin to direct his interlocutor to the area he comes from, and only then to say something about his home village. The same interviewee takes a positive view of the inhabitants of the other region, saying "I really like the people from across the Mureș, they are very friendly, you feel so good there... they are more welcoming than we are, they are more attached to their customs. The people there are first-rate. At first, I was very surprised at how they even take care of their graves, we are more laid back".Moreover, one interviewee (I3) makes a direct comparison between the inhabitants of Crișana and Banat: "Here people are more reserved, they are not so "warm". Over there, across the Mureș, there is a different feel to things. If I go to someone's house, the hostess offers a glass of brandy and my wife is greeted by relatives who show her what they have done, what they have sewn, what they have renovated. They are more open, at the village festival they invite you to their home for a meal. That's what Banat feels like. They are "proud" of how many "guests" they have had at the table". "The people across the Mureș are good householders, more energetic than us" (I19) is another statement from an inhabitant of Vărădia de Mureș. "The people in Banat are different, they are people who still keep animals that used to be raised here, they have more cows than us, they have more horses, we still have 4 horses in the commune and before there were hundreds of horses". This comparison regarding the livestock sector comes from I12, who remembers how flourishing the commune was years ago, when herds of livestock were much larger, and people put much more emphasis on the growth of the agricultural and livestock sector. The inhabitants of Birchiș mention that the people on the other side of the Mureș are "tidier, more tidy, perhaps even better at housekeeping...it depends from person to person" (I22), "they are more gentle, more civilised than us, we are a bit rough" (I23), "decent people, they also use the Mureș, they have a series of streams that flow into the Mureș, they have woods, they have greenery, you can find everything you want, it's a beautiful, picturesque area", "they are all hard-working people, they just need to have somewhere to work and to be strong" (I26), "simple people, but dedicated. The area is beautiful, but people are less united than here' (I31), "they are like us, impulsive” (I35), 'they are richer than us, the main trunk road passes through there' (I36).

4.4. The Voice of Local Residents: Ideas, Visions, Beliefs, Suggestions

One idea put advanced as an opinion by locals wishing to improve the status of the communes where they live is the continuing of work on the King's Tourist Road, which was originally built at the request of King Michael I to facilitate the journey from the royal property in Săvârșin to the spa resort on the other side of the mountain.Another suggestion, put forward by several people, is that the makeup of the local administration needs to be changed. They say that there is a great need for people who are competent, involved, interested, and committed, with innovative visions and ideas, younger and full of positive energy. They also highlight the need for investors and for well-thought-out and well-planned projects. For older people, a primary solution would be to stop young people leaving, to try to make a difference and raise living standards by their own efforts. An example of this is I17, who would like to open a hairdressing salon in the commune at the request of fellow residents who have said they need this service from someone with specialist qualifications. I17 has taken relevant courses, so in the future she wants to open her own business in her home village: "my future is in the city. In the immediate future, I want to open a hairdressing salon at home, but the aim is not to stay here. I intend to work in the city so that I can develop at all levels. At the request of my fellow commune residents, who say they need such services, I have decided to take this step." In addition to all these proposals, several others were put forward, such as the development of the banks of the river Mures, improvements to the gravel and stone quarry, and the attraction of projects to support the development of road infrastructure.

Among residents of the two communes, there is little hope that anything good will appear on the scene to change things in their villages. Most agree that they are struggling against too many obstacles, so very few interviewees mention factors that might lead to progress and development. I2 pins their hopes on the finalisation of the refurbishment of the Vărădia de Mureș village hall: "We had both roads and a village hall... let's hope that measures are taken and that the work started is completed", and in the creation of jobs to cater for as many people as possible who currently commute or have moved elsewhere precisely for this reason: "if jobs appeared, young people would not leave, some of those who have left would return. If only some investors could come, I don't know how, I don't know where from, to give life to the area" (I2).

Consequently, the local administration of these two villages has to consider this aspect in the future policy agendas in order to sustain both the social, cultural and environmental resources as well as the residents’ voices.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper has examined the issue of regional and cultural identity in the rural environment by taking as a case study two Romanian villages that are closely connected to each other by a geographical feature of their region, the river Mureș, which acts as a cultural spine in the formation of rural communities in this region of Romania. In addition, both villages are enriched by social and cultural features and aspects that characterise Romanian rural settlements and illustrate a common identity which is both spatially and mentally represented and is deeply rooted in the local collective memory. The shaping of cultural identity in the sites we studied follows the Romanian and Eastern European model of cultural identity formation, which is founded on the geographical/environmental, social, economic and cultural attributes of places and communities under both constant and changing kinds of political governance. The most important feature defining the specific cultural identity of these two sites is water, which, as their most relevant geographical resource, provides the most distinctive directions for community dynamics and development, giving specific contexts and opportunities for local people, for their social and economic practices and for their way of life, all of which contribute to the construction of a cultural landscape with an identity of its own.

The local people, resources, social practices, symbolism, collective identity, history, and institutional governance of a place are the most important aspects that frame and define its cultural identity [

64,

65,

66]. The people are important because they are the agents in the spatial construction of a place; the environment and physical resources frequently represent the key advantages that sustain local practices in the social, cultural and economic development of a community, which in turn contribute to the construction of local identity.

The quantitative analysis described in this paper has shown that people in Birchiș and Vărădia communes identify themselves with the river Mureș, viewing it as an environmental feature that has contributed to the formation both of these rural localities and of the local cultural identity widely reflected in the cultural landscapes of their villages. They also identify with the entire river valley, since countless villages along the river have benefited from the same opportunities throughout their history, resulting in many similarities in local cultural landscapes and in the inhabitants’ ways of life. The literature on the role of water in local communities has shown the importance of the presence of water and of all the opportunities rivers provide for people and communities [

10,

11,

12,

50]. In our case, the river Mureș represents, both for these rural communities and for the whole region, a significant opportunity for development, even though it is also perceived as a risk factor.

In terms of regional identity as seen through the lens of a sense of belonging, local people feel themselves to be part of the Crișana and Banat regions, which argues for the regional inter- and multiculturalism that frames these rural settlements. In addition, they identify with the rural localities in which they live and pursue their specific ways of life, drawing on all the resources provided by nature and by the cultural and historical heritage. Rural residents express their satisfaction with local social and cultural values and institutions, stressing the importance to them of the local church and religion, schools, and cultural and administrative institutions, with evident reservations as regards the current local authorities, who ought to be enhancing their efforts towards and involvement in local development by properly exploiting the local cultural background and the major environmental resource represented by the river. A change of attitude, policy, and agenda-setting here could undoubtedly aid local economic development, especially via the promotion of tourism and cultural activities. The local uniqueness of these places is illustrated by the historical background that has taken shape over the centuries and under changing political systems, by the local ethnicity and language, by the people themselves, who keep these communities alive, and by local traditions and specific practices of rural life. The local pride shown by people and communities, and the positive relationships between people and between different cultural groups, also make a direct contribution to the construction of the cultural identity of these places. Throughout this quantitative analysis, the cultural landscapes of the country area studied, clearly illustrating as they do the local cultures established over time, are viewed as the major spatial and geographical attribute of these communities.

The qualitative part of the research brings to light people’s feelings and perceptions regarding their cultural traditions, local history, and cultural background, all underexploited in current local development initiatives. The nostalgia and regrets commune residents express flow from their perception that the local administration is insufficiently committed to developing these villages economically by turning their cultural, natural, and human capital to good use. Future policy agendas need to reflect this priority. In our days, the cultural regionality and identity of places and regions have been instrumentalized to become valuable assets that should be inspiring local authorities to make full use of them as means through which communities can be developed in the light of their cultural identity as places with significant cultural potential and resources. Regional identity is therefore connected to the construction and deconstruction of spaces [

24,

25,

26,

27,

67]. Our two rural areas belong to different regions that represent institutionalized places and spaces, which means that their development has been shaped by political and economic factors which created their regional identity [see 29].

In conclusion, narratives, practices, and discourses regarding the cultural identity of places and regions must be given fuller consideration when we are rethinking the contemporary development of rural communities – places whose cultural identities, collective memories, and all their cultural landscapes are defined, in their uniqueness, by people and by their cultures, social practices, and ways of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D. and R.C.; methodology, A.D. and R.C.; software, O.O.; validation, R.C. and S.J.; formal analysis, A.D. and O.O.; investigation, O.O. and A.D.; data curation, O.O. and A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C., S.J. and A.D.; writing—review and editing, R.C. and S.J.; visualization, A.D.; supervision, A.D. and R.C.; funding acquisition, A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript and contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This work was financially supported by a grant of the Romanian Ministry of Education and Research: CNCS/CCCDI-UEFISCDI, project number PN-III-P1-1.1-PD-2019-0274.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous respondents for their positive feedback on this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Banini, T.; Ilovan, O. Representing Place and Territorial Identities in Europe; Springer International Publishing: Dordrecht, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. Place and placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 1976; Volume 67, 156p. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of capital: Towards a critical geography; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; 442p. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. Questions of locality. Geography 1993, 78, 142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Paasi, A. Region and place: regional identity in question. Progress in Human geography 2003, 24, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiculescu, S. Timişoara and the culture of water. In The Romanian post-socialist city: Urban renewal and gentrification; West University of Timisoara Publishing House: Timisoara, 2009; pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sipos, G.; Blanka-Végi, V.; Ardelean., F.; Onaca, A.; Ladányi, Z.; Rácz, A.; Urdea, P. Human-nature relationship and public perception of environmental hazards along the Maros/Mureş River (Hungary and Romania). Geographica Pannonica 2022, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkon, A.; Traugot, M. Place matters, but how? Rural identity, environmental decision making, and the social construction of place. City & Community 2008, 7, 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M. Rural geography: blurring boundaries and making connections. Progress in Human geography 2009, 3, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R. Cultural politics and the hydrosocial cycle: Water, power and identity in the Andean highlands. Geoforum 2014, 57, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R. Water, power and identity: The cultural politics of water in the Andes; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Boelens, R.; Getches, D.; Guevara-Gil, A. Water struggles and the politics of identity. In Out of the Mainstream: Water Rights, Politics and Identity; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Terlouw, K. Iconic site development and legitimating policies: The changing role of water in Dutch identity discourses. Geoforum 2014, 57, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R.; Turnock, D.; Woudstra, J. Identity and multiculturalism in the Romanian Banat. Méditerranée 2008, 110, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berceanu, I.; Popa, N.; Creţan, R. Towards a regional crossover model? The roles played by spatial vicinity and cultural proximity among ethnic minorities in an East-Central European borderland. Journal of Urban and Regional Analysis 2023, 15, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R. Who owns the name? Fandom, social inequalities and the contested renaming of a football club in Timisoara, Romania. Urban Geography 2019, 40, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Porta, D.; Diani, M. Social movements. An introduction; John Wiley and Sons Ltd., 1999; 384p. [Google Scholar]

- Glemain, P.; Bioteau, E.; Dragan, A. Les finances solidaires et l’économie sociale en Roumanie: une réponse de “proximités” à la régionalisation d’une économie en transition? Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 2013, 84, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkli, J.; Paasi, A. Geography, space and identity. Voices from the North; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.; Paasi, A. Guest Editorial: Regional world (s): Advancing the geography of regions. Regional Studies. 2013, 47, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A.; Harrison, J.; Jones, M. Handbook on the Geographies of Regions and Territories; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2018; 544p. [Google Scholar]

- Paasi, A.; Harrison, J.; Jones, M. New consolidated regional geographies. Handbook on the geographies of regions and territories; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Doiciar, C.; Creţan, R. Pandemic populism COVID-19 and the rise of the nationalist AUR party in Romania. Geographica Pannonica 2021, 25, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, M. Governmentality, subject-building, and the discourses and practices of devolution in the UK. Transactions of the institute of British geographers 2003, 28, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, M. Building new subjectivities: devolution, regional identities and the re-scaling of politics. In Territory, Identity and Spatial Planning; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 320–334. [Google Scholar]

- Beel, D.; Jones, M. Region, Place, Devolution: geohistory still matters. In The Routledge Handbook of Place; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Guibernau, M. National identity, devolution and secession in Canada, Britain and Spain. Nations and nationalism 2006, 12, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.; Popa, N. Social Economy in Post-communist Romania: What Kind of Volunteering for What Type of NGOs? Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 2017, 19, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Deconstructing regions: notes on the scales of spatial life. Environment and Planning A 1991, 23, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. The region, identity, and power. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2011, 14, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Regional planning and the mobilization of ‘regional identity’: From bounded spaces to relational complexity. Regional studies 2013, 47, 1206–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, P. Reproduction of the identity of a region: perceptual regions based on formal and functional regions and their boundaries. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 2023, 105, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridanpää, J. Imagining and re-narrating regional identities. Nordia Geographical Publications 2015, 44, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, L.A. Using the past to construct territorial identities in regional planning: The case of Mälardalen, Sweden. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 2017, 41, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anděl, J.; Balej, M.; Bobr, L. Landscape types and regional identity–by example of case study in Northwest Bohemia. AUC Geographica 2019, 54, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonsich, M. ; Meanings of place and aspects of the Self: An interdisciplinary and empirical account. GeoJournal 2010, 75, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlouw, K. Transforming identity discourses to promote local interests during municipal amalgamations. GeoJournal 2018, 83, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvoll, S.; Rye, J.F. Elite discourses of regional identity in a new regionalism development scheme: The case of the ‘Mountain Region’ in Norway. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 2009, 63, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainikka, J. The role of identity for regional actors and citizens in a splintered region: The case of Päijät-Häme, Finland. Fennia-International Journal of Geography 2013, 191, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semian, M.; Chromý, P. Regional identity as a driver or a barrier in the process of regional development: A comparison of selected European experience. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift-Norwegian Journal of Geography 2014, 68, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Engaging the global countryside: globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place. Progress in Human geography 2007, 31, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.; Utych, S.M. You’re not from here!: The consequences of urban and rural identities. Political Behavior 2021, 45, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, S. Rural identities: Ethnicity and community in the contemporary English countryside; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Molnárová, K.J.; Skřivanová, Z.; Kalivoda, O.; Sklenička, P. Rural identity and landscape aesthetics in exurbia: Some issues to resolve from a Central European perspective. Moravian Geographical Reports 2017, 25, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezák, P.; Dobrovodská, M. Role of rural identity in traditional agricultural landscape maintenance: the story of a post-communist country. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 2019, 43, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.; Leal, J. Rural tourism and national identity building in contemporary Europe: Evidence from Portugal. Journal of Rural Studies 2015, 38, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, A. Rurality, identity and morality in remote rural areas in northern Spain. Journal of Rural Studies 2014, 35, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, N. Bridging identity divides in current rural social mobilisation. Identities 2013, 20, 598–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messely, L.; Dessei, J.; Lauwers, L.H. Regional identity in rural development: three case studies of regional branding. Applied Studies in Agribusiness and Commerce 2010, 4, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, V. Substantial connections: Water and identity in an English cultural landscape. Worldviews. Global Religions 2006, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatout, S. ‘States’ of scarcity: water, space, and identity politics in Israel, 1948–1959. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2008, 26, 959–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oestigaard, T. Water, Culture and Identity: Comparing past and present traditions in the Nile Basin region; BRIC: London, UK, 2009; 272p. [Google Scholar]

- Ruru, J. The right to water as the right to identity: legal struggles of indigenous peoples of Aotearoa New Zealand. In The Right to Water; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Bilotta, E.; Bonnes, M.; Ceccarelli, M.; Martorella, H.; Carrus, G. Local identity and the role of individual differences in the use of natural resources: The case of water consumption. Journal of applied social psychology 2008, 38, 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R. Water, Power and Identity: The Cultural Politics of Water in the Andes (Earthscan Studies in Water Resource Management); Routledge: London, UK, 2015; 387p. [Google Scholar]

- Cloke, P.; Cook, I.; Crang, P.; Goodwin, M.; Painter, J.; Philo, C. Practicing human geography; Sage: London, UK, 2000; 440p. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, D.H.; Herb, G.H. How geography shapes national identities. National Identities. 2011, 13, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, M.; Alem, N.; Edwards, S.J.; Blanco Coariti, E.; Cauthin, H.; Hudson-Edwards, K.A.; Sánchez, M.O. Community exposure and vulnerability to water quality and availability: a case study in the mining-affected Pazña Municipality, Lake Poopó Basin, Bolivian Altiplano. Environmental Management 2017, 60, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamfir, D.; Stoica, I.V. Demographic Changes and Challenges of Small Towns in Romania. In Urban Dynamics, Environment and Health; Sinha, B.R.K., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dragan, A.; Crețan, R.; Bulzan, R. The spatial development of peripheralisation: The case of smart city projects in Romania. Area 2023, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSEE. Statistical data. The Romanian Institute of Statistics/Tempo Online. 2023. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro/shop/.

- Ianoș, I.; Cocheci, R.-M.; Petrișor, A.-I. Exploring the Relationship between the Dynamics of the Urban–Rural Interface and Regional Development in a Post-Socialist Transition. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qualitative Research 2006, 6, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R.; Covaci, R.N.; Jucu, I.S. Articulating ‘otherness’ within multiethnic rural neighbourhoods: Encounters between Roma and non-Roma in an East-Central European borderland. Identities 2023, 30, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancuța, C.; Jucu, I.S. Sustainable Rural Development through Local Cultural Heritage Capitalization—Analyzing the Cultural Tourism Potential in Rural Romanian Areas: A Case Study of Hărman Commune of Brașov Region in Romania. Land 2023, 12, 1297–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T.; Creţan, R.; Jucu, I.S.; Covaci, R.N. Internal migration and stigmatization in the rural Banat region of Romania. Identities 2023, 30, 704–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, N.; Dragan, A.; Marian-Potra, A.C.; Matichescu, M.L. Opportunities: Source of synergy, or of conflict? Positioning of creative industry actors within a European Capital of Culture Project. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0274093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).