Submitted:

20 June 2024

Posted:

21 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Significance of the Study

Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

Study Site

Study Design and Population

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Sampling Methods

Ethical Approval

Sample size Determination

Data Analysis

3. Results

Concept of Emotional Labor Force among Nurses and Clinicians and Its Implications on Their Well-Being and Job Performance

“The comfort and happiness of my patient is my first priority, … one of my job’s standards is to suppress my negative emotions and express myself in a way that is acceptable to my patients, therefore even if the patient said anything that made me feel upset, I still try to console and ease their pain.”(Participant 2, FGD 2)

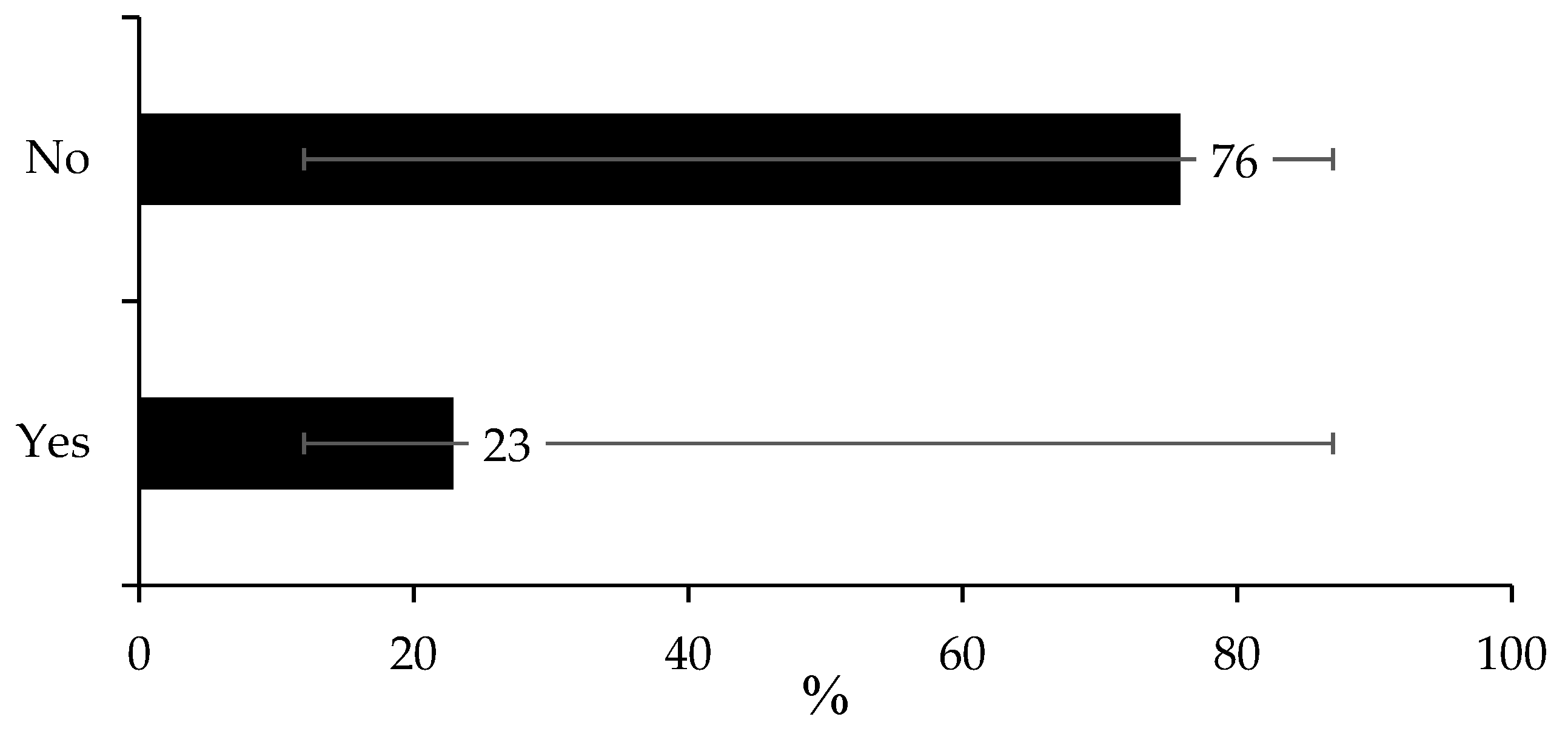

Implications of Emotional Disturbance

“Whenever I am emotionally disturbed, I get irritated, overthink everything, and worry about my job, which makes me quite tired by the end of the day.”(Participant 2, FDH 3)

“There are instances when being disturbed makes me moody, which reduces my performance at work and the quality of care I provide to my patients.”(Participant 4, FDG 2)

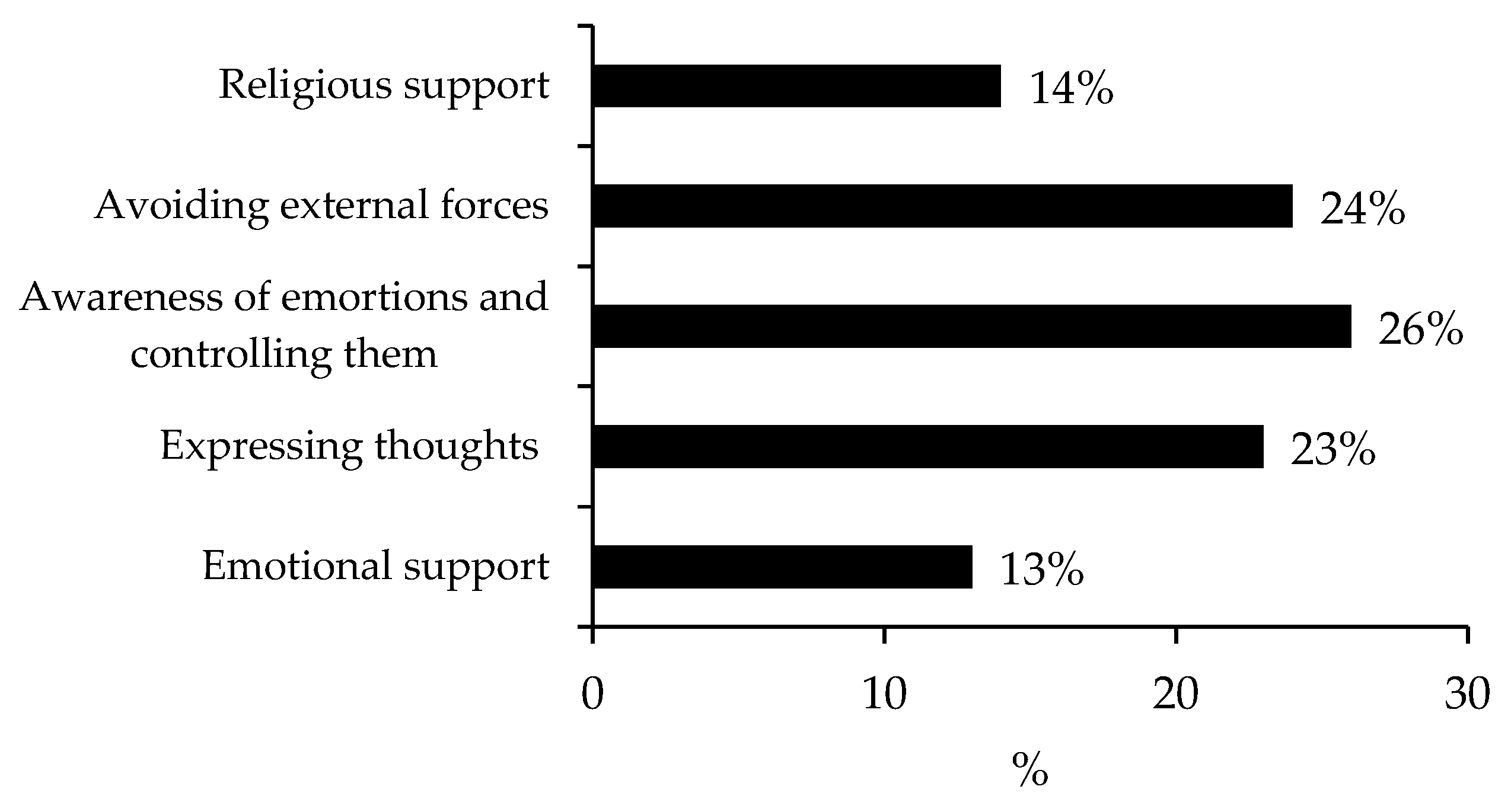

Factors Associated with Emotional Disturbance

“We always try to avoid a scenario as much as we can, we manage our emotions, and occasionally, we employ counseling to help the offender and the offended come to an understanding.”(Participant 5, FDG 2)

“In order to prevent emotional harm that results in bad emotional wellness and the nurse-patient connection, I wanted to emphasize that if training were implemented for the emotional labor force, it would assist us to be conscious of our emotions, how to deal with them, and where to go if such situations arise.”(Participant 1, FGD 3)

“I wanted to make the point that it would be beneficial if we could have well-trained health professionals who could offer emotional support and conduct mental health and wellbeing screenings, as doing so could improve the standard of treatment provided to patients.”(Participant, 7 FGD 1)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Declaration for Human Participants

Conflicts of Interests

Data availability

Authors’ contributions

References

- Hochschild AR. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2012.

- Dubale BW, Friedman LE, Chemali Z, Denninger JW, Mehta DH, Alem A, Fricchione GL, Dossett ML, Gelaye B. Systematic review of burnout among healthcare providers in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC public health. 2019 Dec;19:1-20. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Xu P, Zhou K, Xue J, Wu H. Mediating role of emotional labor in the association between emotional intelligence and fatigue among Chinese doctors: a cross-sectional study. BMC public health. 2018 Dec;18:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor force statistics from the current population survey. https://www.bls.gov/cps/. 2018.

- Kim MH, Mazenga AC, Yu X, Simon K, Nyasulu P, Kazembe PN, Kalua T, Abrams E, Ahmed S. Factors associated with burnout amongst healthcare workers providing HIV care in Malawi. PLoS One. 2019 Sep 24;14(9):e0222638. [CrossRef]

- Suh C, Punnett L. High emotional demands at work and poor mental health in client-facing workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022 Jun 20;19(12):7530. [CrossRef]

- Owuor RA, Mutungi K, Anyango R, Mwita CC. Prevalence of burnout among nurses in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. JBI Evidence Synthesis. 2020 Jun 1;18(6):1189-207. [CrossRef]

- Koen L, Niehaus DJ, Smit IM. Burnout and job satisfaction of nursing staff in a South African acute mental health setting. South African Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;26. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed F, Hawulte B, Yuya M, Birhanu S, Oljira L. Prevalence of burnout and associated factors among health professionals working in public health facilities of Dire Dawa city administration, Eastern Ethiopia. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022 Aug 11;10:836654. [CrossRef]

- Singano FK, Mazengera R, Mbendela I, Singano V. High burnout among maternity healthcare workers in Zomba and Lilongwe, Malawi [Internet]. Research Square. 2023. Available from: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3032062/v1.

- Tsukamoto SA, Galdino MJ, Barreto MF, Martins JT. Burnout syndrome and workplace violence among nursing staff: a cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Medical Journal. 2021 Dec 17;140:101-7. [CrossRef]

- Karimi L, Leggat SG, Donohue L, Farrell G, Couper GE. Emotional rescue: The role of emotional intelligence and emotional labour on well-being and job-stress among community nurses. Journal of advanced nursing. 2014 Jan;70(1):176-86. [CrossRef]

- Lartey JK, Osafo J, Andoh-Arthur J, Asante KO. Emotional experiences and coping strategies of nursing and midwifery practitioners in Ghana: a qualitative study. BMC nursing. 2020 Dec;19:1-2. [CrossRef]

- Chaabane S, Chaabna K, Bhagat S, Abraham A, Doraiswamy S, Mamtani R, Cheema S. Perceived stress, stressors, and coping strategies among nursing students in the Middle East and North Africa: an overview of systematic reviews. Systematic reviews. 2021 May 5;10(1):136. [CrossRef]

- Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: Past, present, future. Cognition & emotion. 1999 Sep 1;13(5):551-73. [CrossRef]

- National Statistical Office. 2018 Malawi Population and Housing Census. [Internet]. 2019. Available from: http://www.nsomalawi.mw/images/stories/data_on_line/demography/census_2018/2018%20Malawi%20Population%20and%20Housing%20Census%20Main%20Report.pdf.

- Yamane, T. Statisics An Introductory Analysis. New York. 1967;2.

- Blankson-Stiles-Ocran S, Amissah EF, Mensah AO. Determinants of emotional labour among employees in the hospitality industry in Accra, Ghana. AJHTM. 2019 Jun 19;1(1):48–66. [CrossRef]

- Hailay A, Aberhe W, Mebrahtom G, Zereabruk K, Gebreayezgi G, Haile T. Burnout among Nurses Working in Ethiopia. Behav Neurol. 2020;2020:8814557. [CrossRef]

- Peters DH, Chakraborty S, Mahapatra P, Steinhardt L. Job satisfaction and motivation of health workers in public and private sectors: cross-sectional analysis from two Indian states. Hum Resour Health. 2010 Dec;8(1):27. [CrossRef]

- Kawale P, Pagliari C, Grant L. What does the Malawi Demographic and Health Survey say about the country’s first Health Sector Strategic Plan? Journal of Global Health. 2019 Jun;9(1):010314.

- Ahmat A, Okoroafor SC, Kazanga I, Asamani JA, Millogo JJS, Illou MMA, et al. The health workforce status in the WHO African Region: findings of a cross-sectional study. BMJ Glob Health. 2022 May;7(Suppl 1):e008317. [CrossRef]

- Dias JC, Silva SC, Rosario A. Emotional labor in healthcare: the role of work perceptions and personality traits. Academy of Strategic Management Journal. 2022;21(6).

- Portoghese I, Galletta M, Leiter MP, Cocco P, D’Aloja E, Campagna M. Fear of future violence at work and job burnout: A diary study on the role of psychological violence and job control. Burnout Research. 2017 Dec;7:36–46. [CrossRef]

- Poku CA, Donkor E, Naab F. Determinants of emotional exhaustion among nursing workforce in urban Ghana: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2020 Dec;19(1):116. [CrossRef]

- Marine A, Ruotsalainen J, Serra C, Verbeek J. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Oct 18;(4):CD002892.

- Kinman G, Leggetter S. Emotional Labour and Wellbeing: What Protects Nurses? Healthcare (Basel). 2016 Nov 30;4(4):89.

| Variable | n | Proportion | 95% LCL | 95% UCL |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 33 | 39% | 29% | 50% |

| Female | 51 | 61% | 50% | 71% |

| Age range in years | ||||

| 20 - 29 | 23 | 27% | 19% | 38% |

| 30 - 39 | 40 | 48% | 37% | 58% |

| 40 - 49 | 16 | 19% | 12% | 29% |

| 50 - 59 | 5 | 6% | 2% | 14% |

| Education level | ||||

| Certificate | 9 | 11% | 6% | 19% |

| Diploma | 57 | 68% | 57% | 77% |

| Degree | 18 | 21% | 14% | 32% |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 33 | 39% | 29% | 50% |

| Married | 51 | 61% | 50% | 71% |

| Work experience | ||||

| Less than five years | 37 | 44% | 34% | 55% |

| Five to ten years | 27 | 32% | 23% | 43% |

| Ten years above | 20 | 24% | 16% | 34% |

| Cadre | ||||

| Nurse | 62 | 74% | 63% | 82% |

| Clinician | 20 | 24% | 16% | 34% |

| Medical doctor | 2 | 2% | 1% | 9% |

| Department | ||||

| Male ward | 9 | 11% | 6% | 19% |

| Maternity | 31 | 37% | 27% | 48% |

| Pediatric | 10 | 12% | 6% | 21% |

| Female ward | 8 | 10% | 5% | 18% |

| OPD | 23 | 27% | 19% | 38% |

| Theater | 3 | 4% | 1% | 11% |

| LCL = Lower Confidence Level, UCL = Upper Confidence Level | ||||

| Never | 1 - 5 times a month | > 5 times a month | ||

| Emotional disturbance | (n, %) | (n, %) | (n, %) | p value |

| Emotionally tired | 11(13%) | 50(60%) | 23(27%) | <0.001* |

| Depression | 62(74%) | 18(21%) | 4(5%) | <0.001* |

| Verbal abuse | 10(12%) | 49(58%) | 25(30%) | <0.001* |

| Physical abuse | 81(96%) | 3(4%) | <0.001* | |

| Stress and anger | 10(12%) | 48(57%) | 26(31%) | <0.001* |

| Emotionally tired | Depression | Verbal abuse | Physical abuse | Stress and anger | |

| Variable | χ2(p value) | χ2 (p value) | χ2 (p value) | χ2 (p value) | χ2 (p value) |

| Sex | 2.321 (0.313) | 4.951 (0.084**) | 1.565 (0.457) | 0.046 (0.830) | 4.208 (0.122) |

| Age | 12.027 (0.061**) | 13.536 (0.035*) | 7.947 (0.242) | 4.874 (0.181) | 12.358 (0.054**) |

| Education | 6.226 (0.183) | 9.225 (0.056**) | 2.307 (0.679) | 0.54 (0.763) | 3.611 (0.461) |

| Experience | 5.44 (0.245) | 11.113 (0.025*) | 3.258 (0.516) | 1.104 (0.576) | 10.450 (0.033*) |

| Cardre | 3.302 (0.509) | 9.685 (0.046*) | 3.693 (0.449) | 1.104 (0.576) | 5.761 (0.218) |

| Department | 8.477 (0.004*) | 17.33 (0.067**) | 14.98 (0.035*) | 2.876 (0.071**) | 27.472 (0.002*) |

| Work environment | 5.433 (0.246) | 5.751 (0.218) | 5.183 (0.269) | 0.203 (0.903) | 5.888 (0.208) |

| Staffing | 2.358 (0.308) | 10.733 (0.005*) | 2.099 (0.350) | 0.283 (0.595) | 2.069 (0.355) |

| Policies | 6.381 (0.172) | 4.779 (0.311) | 1.786 (0.775) | 12.913 (0.002*) | 2.046 (0.727) |

| Work demand | 2.102 (0.047*) | 9.786 (0.044*) | 4.453 (0.348) | 0.789 (0.674) | 16.384 (0.003*) |

| **Association is significant at p<0.1 level (2-tailed). *Association is significant at p<0.05 level (2-tailed) | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).