Submitted:

20 June 2024

Posted:

21 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Population and Blood Serum Indicators

2.2. Genotyping and Quality Control

2.3. Estimation of Genetic Parameters

2.4. Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

2.5. Functional Annotation Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic Correlation and Genetic Parameter Analyses between Serum Biochemical Indicators

| Traits | ALT | AST | CHO | LDH | CA | IP | CRE | GLU | TPRO | UREA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT | 0.21 ± 0.11 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.49 ± 0.04 | -0.01 ± 0.05 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | -0.01 ± 0.05 | 0.02 ± 0.05 | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 0.09 ± 0.05 |

| AST | 0.91 ± 0.08 | 0.14 ± 0.10 | 0.40 ± 0.04 | 0.53 ± 0.04 | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.05 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 0.27 ± 0.04 |

| CHO | 0.48 ± 0.16 | 0.77 ± 0.12 | 0.43 ± 0.14 | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 0.32 ± 0.04 |

| LDH | 0.82 ± 0.08 | 0.87 ± 0.07 | 0.70 ± 0.13 | 0.36 ± 0.14 | 0.14 ± 0.05 | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.06 |

| CA | -0.03 ± 0.20 | 0.64 ± 0.12 | 0.39 ± 0.11 | 0.36 ± 0.14 | 0.27 ± 0.13 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 0.28 ± 0.04 |

| IP | 0.84 ± 0.23 | 0.88 ± 0.33 | 0.53 ± 0.14 | 0.80 ± 0.15 | 0.37 ± 0.17 | 0.29 ± 0.13 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.04 | -0.10 ± 0.05 |

| CRE | -0.04 ± 0.22 | 0.66 ± 0.12 | 0.42 ± 0.11 | 0.28 ± 0.14 | 0.11 ± 0.06 | 0.35 ± 0.19 | 0.20 ± 0.11 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.04 |

| GLU | 0.13 ± 0.23 | 0.77 ± 0.34 | 0.54 ± 0.19 | 0.78 ± 0.25 | 0.61 ± 0.14 | 0.76 ± 0.24 | 0.62 ± 0.15 | 0.15 ± 0.10 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | -0.11 ± 0.05 |

| TPRO | 0.71 ± 0.12 | 0.81 ± 0.09 | 0.81 ± 0.07 | 0.98 ± 0.08 | 0.64 ± 0.09 | 0.80 ± 0.13 | 0.64 ± 0.10 | 0.59 ± 0.17 | 0.55 ± 0.14 | 0.21 ± 0.04 |

| UREA | 0.27 ± 0.32 | 0.73 ± 0.17 | 0.74 ± 0.14 | 0.29 ± 0.34 | 0.76 ± 0.16 | -0.52 ± 0.38 | 0.78 ± 0.15 | -0.63 ± 0.46 | 0.59 ± 0.18 | 0.18 ± 0.11 |

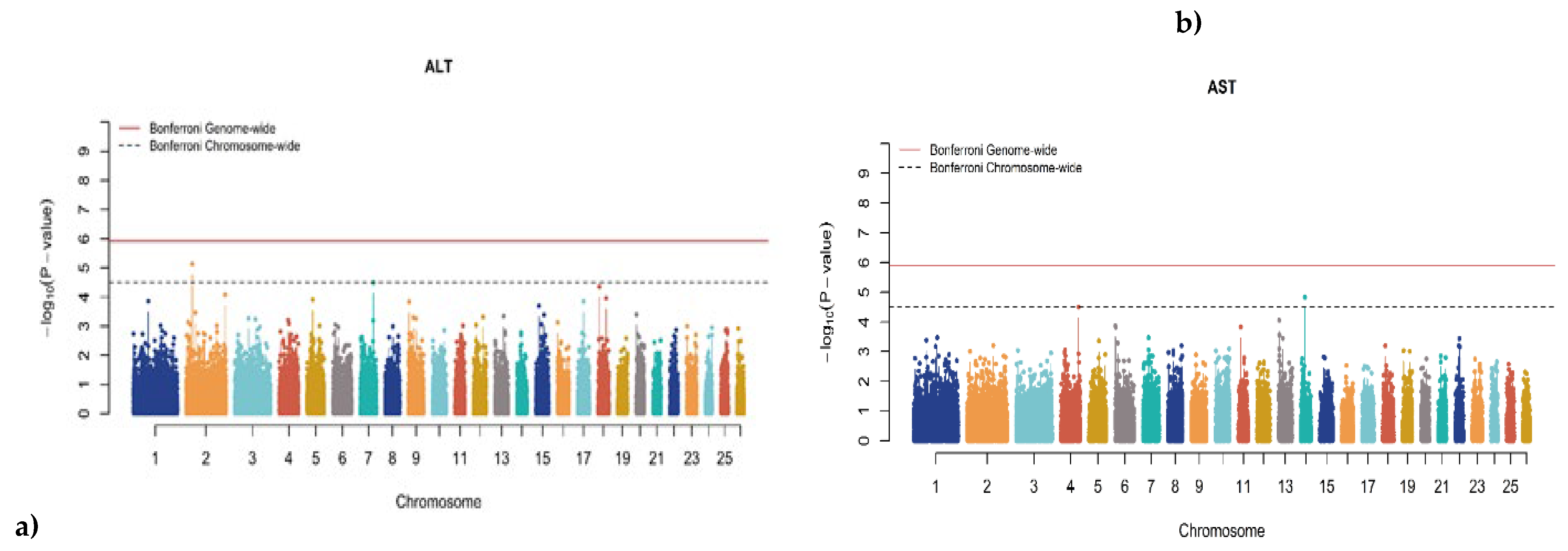

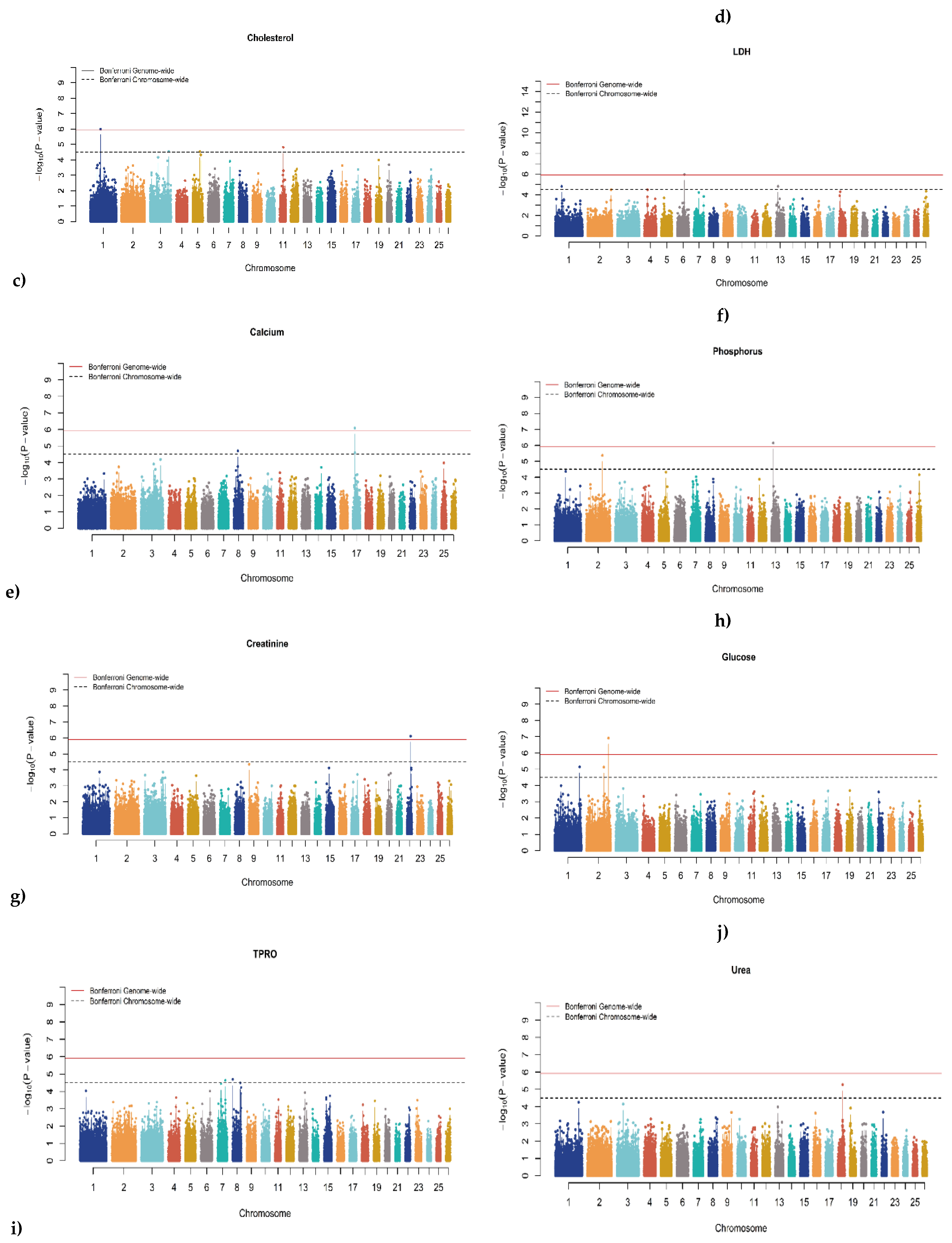

3.2. Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

| Trait | SNP | Chr | Oar_v4.0 Position (bp) |

P-Value | MAF | Effect Size | Candidate Gene | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHO | rs415766081 | 1 | 107,828,780 | 1.022×10-06 | 0.110 | 0.084 | Spectrin alpha, erythrocytic 1 (SPTA1) | Intron variant |

| CA | rs427096440 | 17 | 17,753,256 | 8.033×10-07 | 0.414 | 0.004 | Microsomal glutathione S-transferase 2 (MGST2) | ~31 Kb upstream |

| CRE | rs423178582 | 22 | 37,960,974 | 7.716×10-07 | 0.157 | 0.068 | CDK2 associated cullin domain 1 (CACUL1) | ~42 Kb upstream |

| GLU | rs428784360 | 2 | 227,357,948 | 1.207×10-07 | 0.160 | 0.092 | ENSOARG00020040484.1 | Intron variant |

| LDH | rs410665381 | 6 | 72,632,996 | 1.216×10-06 | 0.129 | 0.117 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) | ~267 Kb upstream |

| IP | rs404995480 | 13 | 17,678,848 | 6.902×10-07 | 0.388 | 0.063 | Par-3 family cell polarity regulator (PARD3) | Intron variant |

| Trait | SNP | Chr | Oar_v4.0 Position (bp) |

P-Value | MAF | Effect Size | Candidate Gene | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHO | rs415259159 | 11 | 36,648,365 | 1.536×10-05 | 0.417 | 0.047 | Prohibitin 1 (PHB1) | ~35 Kb upstream |

| CHO | rs408900631 | 3 | 198,343,644 | 2.820×10-05 | 0.432 | 0.047 | Solute Carrier Family 15 Member 5 (SLC15A5) | ~55 Kb downstream |

| CHO | rs403535835 | 5 | 75,927,368 | 2.923×10-05 | 0.101 | 0.073 | LOC101117162 | ~19 Kb upstream |

| ALT | rs413251030 | 2 | 38,421,272 | 7.175×10-06 | 0.194 | 0.380 | Tripartite Motif Containing 35 (TRIM35) | ~71 Kb downstream |

| ALT | rs421887664 | 7 | 80,842,728 | 3.158×10-05 | 0.158 | 0.439 | Regulator Of G-Protein Signaling 6 (RGS6) | Intron variant |

| AST | rs405842437 | 14 | 24,175,813 | 1.453×10-05 | 0.449 | 0.013 | Nucleoporin 93 (NUP93) | Intron variant |

| AST | rs423986212 | 4 | 109,758,783 | 3.111×10-05 | 0.269 | 0.014 | Contactin Associated Protein 2 (CNTNAP2) | Intron variant |

| CA | rs421266853 | 8 | 39,031,937 | 1.967×10-05 | 0.417 | 0.003 | LOC105611309 | ~56 Kb downstream |

| CA | rs408365736 | 17 | 19,135,137 | 2.576×10-05 | 0.077 | 0.006 | Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 (SLC7A11) | Intron variant |

| GLU | rs412782784 | 1 | 257,987,356 | 7.143×10-06 | 0.067 | 0.118 | Beta-1,3-Galactosyltransferase 5 (B3GALT5) | ~288 Kb downstream |

| GLU | rs410943504 | 2 | 178,724,382 | 7.415×10-06 | 0.457 | 0.059 | Dipeptidyl Peptidase Like 10 (DPP10) | Intron variant |

| LDH | rs402703943 | 1 | 63,683,463 | 1.665×10-05 | 0.218 | 0.090 | Heparan Sulfate 2-O-Sulfotransferase 1 (HST2ST1) | ~185 Kb downstream |

| LDH | rs410138359 | 13 | 18,806,069 | 1.678×10-05 | 0.169 | 0.087 | Neuropilin 1 (NRP1) | ~44 Kb downstream |

| IP | rs420848991 | 2 | 168,420,121 | 4.201×10-06 | 0.191 | 0.077 | LDL Receptor Related Protein 1B (LRP1B) | Intron variant |

| TPRO | rs423075621 | 8 | 963,780 | 2.017×10-05 | 0.488 | 0.045 | LOC101118029 | ~74 Kb upstream |

| TPRO | rs401111582 | 7 | 79,289,788 | 2.319×10-05 | 0.386 | 0.044 | Mitogen-Activated Protein 3 Kinase 9 (MAP3K9) | Intron variant |

| UREA | rs403791299 | 18 | 48,405,490 | 5.277×10-06 | 0.432 | 1.971 | LOC101103187 | ~127 Kb upstream |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bobbo, T.; Ruegg, P. L.; Fiore, E.; Gianesella, M.; Morgante, M.; Pasotto, D.; Cecchinato, A. Association between udder health status and blood serum proteins in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 2017, 100, 9775-9780. [CrossRef]

- Psychogios, N.; Hau, D.D.; Peng, J.; Guo, A.C.; Mandal, R.; Bouatra, S.; Wishart, D.S. The human serum metabolome. PloS One 2011, 6, e16957. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Kastenmüller, G.; He, Y.; Belcredi, P.; Möller, G.; Prehn, C.; Wang-Sattler, R. Differences between human plasma and serum metabolite profiles. PloS One 2011, 6, e21230. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T.E.; Verwoert, G.C.; Hwang, S.J.; Glazer, N.L.; Smith, A.V.; van Rooij, F.J.A.; Ehret, G.B.; Boerwinkle, E.; Felix, J.F.; Leak, T.S.; Harris, T.B.; Yang, Q.; Dehghan, A.; Aspelund, T.; Katz, R.; Homuth, G.; Kocher, T.; Rettig, R.; Ried, J.S.; Gieger, C.; Prucha, H.; Pfeufer, A.; Meitinger, T.; Coresh, J.; Hofman, A.; Sarnak, M.J.; Chen, Y.D.I.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Chakravarti, A.; Psaty, B.M.; van Duijn, C.M.; Linda-Kao, W.H.; Witteman, J.C.M.; Gudnason, V.; Siscovick, D.S.; Fox, C.S.; Köttgen, A. Genome-wide association studies of serum magnesium, potassium, and sodium concentrations identify six loci influencing serum magnesium levels. PLoS Genet 2010, 6. [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Li, W.; Li,Y.; Zhai, B.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Han, R.; Sun, G.; Jiang, R.; Li, Z.; Yan, F.; Li, G.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Kang, X. Genome-wide association study of 17 serum biochemical indicators in a chicken F2 resource population. BMC Genomics 2023, 24, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C.; Newhouse, S.J.; Braund, P.; Zhang, F.; Tobin, M.; Falchi, M.; Ahmadi, K.; Dobson, R.J.; Marçano, A.C.B.; Hajat, C.; Burton, P.; Deloukas, P.; Brown, M.; Connell, J.M.; Dominiczak, A.; Lathrop, G.M.; Webster, J.; Farrall, M.; Spector, T.; Samani, N.J.; Caulfield, M.J.; Munroe, P.B. Genome-wide Association Study Identifies Genes for Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Disease: Serum Urate and Dyslipidemia. AJHG 2008, 82, 139–149. [CrossRef]

- Bovo, S.; Mazzoni, G.; Bertolini, F.; Schiavo, G.; Galimberti, G.; Gallo, M.; Dall’Olio, S.; Fontanesi, L. Genome-wide association studies for 30 haematological and blood clinical-biochemical traits in Large White pigs reveal genomic regions affecting intermediate phenotypes. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Escribano, B.M.; Molina, A.; Valera, M.; Tovar, P.; Agüera, E.I.; Santisteban, R.; Vivo, R.; Agüera, S.; Rubio, M.D. Genetic analysis of haematological and plasma biochemical parameters in the Spanish purebred horse exercised on a treadmill. Animal 2013, 7, 1414–1422. [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, J.B. Genetics of Biochemical Phenotypes. Twin Res Hum Genet 2020, 23, 77–79. [CrossRef]

- Gieger, C.; Geistlinger, L.; Altmaier, E.; De Angelis, M.H.; Kronenberg, F.; Meitinger, T.; Mewes, H.W.; Wichmann, H.E.; Weinberger, K.M.; Adamski, J.; Illig, T.; Suhre, K. Genetics meets metabolomics: A genome-wide association study of metabolite profiles in human serum. PLoS Genet 2008, 4. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, B.D.; Kammerer, C.M.; Blangero, J.; Mahaney, M.C.; Rainwater, D.L.; Dyke, B.; Hixson, J.E.; Henkel, R.D.; Sharp, R.M.; Comuzzie, A.G.; VandeBerg, J.L.; Stern, M.P.; MacCluer, J.W. Genetic and environmental contributions to cardiovascular risk factors in mexican americans. Circulation 1996, 94, 2159–2170. [CrossRef]

- Zamani, P.; Mohammadi, H.; Mirhoseini, S.Z. Genome-wide association study and genomic heritabilities for blood protein levels in Lori-Bakhtiari sheep. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Andjelić, B.; Djoković, R.; Cincović, M.; Bogosavljević-Bošković, S.; Petrović, M.; Mladenović, J.; Čukić, A. Relationships between milk and blood biochemical parameters and metabolic status in dairy cows during lactation. Metabolites 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Bovo, S.; Mazzoni, G.; Galimberti, G.; Calò, D.G.; Fanelli, F.; Mezzullo, M.; Schiavo, G.; Manisi, A.; Trevisi, P.; Bosi, P.; Dall’Olio, S.; Pagotto, U.; Fontanesi, L. Metabolomics evidences plasma and serum biomarkers differentiating two heavy pig breeds. Animal 2016, 10, 1741–1748. [CrossRef]

- Karisa, B.K.; Thomson, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Montanholi, Y.R.; Miller, S.P.; Moore, S.S.; Plastow, G.S. Plasma metabolites associated with residual feed intake and other productivity performance traits in beef cattle. Livest Sci 2014, 165, 200–211. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Akanno, E.C.; Valente, T.S.; Abo-Ismail, M.; Karisa, B.K.; Wang, Z.; Plastow, G.S. Genomic Heritability and Genome-Wide Association Studies of Plasma Metabolites in Crossbred Beef Cattle. Front Genet 2020, 11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.L.; Xu, Z.Q.; Yang, L.L.; Wang, Y.X.; Li, Y.M.; Dong, J.Q.; Zhang, X.Y.; Jiang, X.Y.; Jiang, X.F.; Li, H.; Zhang, D.X.; Zhang, H. Genetic parameters for the prediction of abdominal fat traits using blood biochemical indicators in broilers. Br Poult Sci 2018, 59, 28–33. [CrossRef]

- FAO. The state of the world’s animal genetic resources for food and agriculture. FAO, Rome, Italy, 2008.

- Scherf, B.D.; Pilling, D. The second report on the state of the world’s animal genetic resources for Food and Agriculture. FAO, Rome, Italy, 2015.

- Bishop, S.C.; Woolliams, J.A. Genomics and disease resistance studies in livestock. Livest Sci 2014, 166, 190–198. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, S.C.; Axford, R.F.E.; Nicholas, F.W.; Owen, J.B. Breeding for disease resistance in farm animals. CABI, UK, 2010.

- Arzik, Y.; Kizilaslan, M.; White, S. N.; Piel, L. M.; Cinar, M. U. Estimates of genomic heritability and genome-wide association studies for blood parameters in Akkaraman sheep. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 18477. [CrossRef]

- Chinchilla-Vargas, J.; Kramer, L.M.; Tucker, J.D.; Hubbell, D.S.; Powell, J.G.; Lester, T.D.; Backes, E.A.; Anschutz, K.; Decker, J.E.; Stalder, K.J.; Rothschild, M.F.; Koltes, J.E. Genetic basis of blood-based traits and their relationship with performance and environment in beef cattle at weaning. Front Genet 2020, 11, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Kizilaslan, M.; Arzik, Y.; White, S.N.; Piel, L.M.W.; Cinar, M.U. Genetic Parameters and Genomic Regions Underlying Growth and Linear Type Traits in Akkaraman Sheep. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13, 1414. [CrossRef]

- Mucha, S.; Mrode, R.; Coffey, M.; Kizilaslan, M.; Desire, S.; Conington, J. Genome-wide association study of conformation and milk yield in mixed-breed dairy goats. J Dairy Sci 2018, 101, 2213–2225. [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, J.C.M. Prediction of response to marker-assisted and genomic selection using selection index theory. J Anim Breed Genet 2007, 124, 331–341. [CrossRef]

- Doormaal, B.V. Increased rates of genetic gain with genomics. Canadian Dairy Network, Canada, 2012; 1–3.

- Goddard, M.E.; Hayes, B.J. Mapping genes for complex traits in domestic animals and their use in breeding programmes. Nat Rev Genet 2009, 10, 381–391. [CrossRef]

- Meuwissen, T.; Hayes, B.; Goddard, M. Accelerating improvement of livestock with genomic selection. Annu Rev Anim Biosci 2013, 1, 221–237. [CrossRef]

- Rupp, R.; Mucha, S.; Larroque, H.; McEwan, J.; Conington, J. Genomic application in sheep and goat breeding. Anim Front 2016, 6, 39–44. [CrossRef]

- Banstola, A.; Reynolds, J.N.J. The Sheep as a Large Animal Model for the Investigation and Treatment of Human Disorders. Biology 2022, 11, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Pinnapureddy, A.R.; Stayner, C.; McEwan, J.; Baddeley, O.; Forman, J.; Eccles, M.R. Large animal models of rare genetic disorders: Sheep as phenotypically relevant models of human genetic disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2015, 10, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Niu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Ning, C.; Yue, S.; Hu, C.; Wang, Z. Identification of whole-genome significant single nucleotide polymorphisms in candidate genes associated with serum biochemical traits in Chinese Holstein cattle. Front Genet 2020, 11, 163. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, D.; Wang, Z.; Yu, D.; Fan, W.; Zhou, Z. Genome-wide association study reveals the genetic determinism of serum biochemical indicators in ducks. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 856. [CrossRef]

- Kizilaslan, M.; Arzik, Y.; Behrem, S.; White, S.N.; Cinar, M.U. Comparative genomic characterization of indigenous fat-tailed Akkaraman sheep with local and transboundary sheep breeds. Food Eng Sec 2024, 13, e508. [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; Emerson, M.; Garner, P.; Holgate, S.T.; Howells, D.W.; Karp, N.A.; Lazic, S.E.; Lidster, K.; MacCallum, C.J.; Macleod, M.; Pearl, E.J.; Petersen, O.H.; Rawle, F.; Reynolds, P.; Rooney, K.; Sena, E.S.; Silberberg, S.D.; Steckler, T.; Würbel, H. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PloS Biol 2020, 18, e3000410. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Vienna, Austria, 2021.

- Breusch, T.S.; Pagan, A.R. A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica 1979, 47, 1287–1294. [CrossRef]

- Box, G.E.P.; Cox, D.R. An analysis of transformations. J R Stat: Series B (Methodological) 1964, 26, 211–243. [CrossRef]

- Aulchenko, Y.S.; Ripke, S.; Isaacs, A.; van Duijn, C.M. GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1294–1296. [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias-Pazaran, G. Genome-Assisted prediction of quantitative traits using the r package sommer. PLoS One 2016, 11, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- VanRaden, P.M. Efficient methods to compute genomic predictions. J Dairy Sci 2008, 91, 4414–4423. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Van der Werf, J.H.J. MTG2: an efficient algorithm for multivariate linear mixed model analysis based on genomic information. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 1420– 1422. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.T. On the use of marginal likelihood in time series model estimation. J R Stat: Series B (Methodological) 1989, 51, 15–27. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.; Walsh, B. Genetics and analysis of quantitative traits. Sinauer, United States, 1998.

- Astle, W.; Balding, D.J. Population structure and cryptic relatedness in genetic association studies. Stat Sci 2009, 24, 451–471. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.M.; Abecasis, G.R. Family-based association tests for genomewide association scans. AJHG 2007, 81, 913–926. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, B.; Roeder, K. Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics 1999, 55, 997–1004. [CrossRef]

- Rangwala, S.H.; Kuznetsov, A.; Ananiev, V.; Asztalos, A.; Borodin, E.; Evgeniev, V.; Joukov, V.; Lotov, V.; Pannu, R.; Rudnev, D. Accessing NCBI data using the NCBI Sequence Viewer and Genome Data Viewer (GDV). Genome Res 2021, 31, 159–169. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res 2009a, 37, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 2009b, 4, 44–57. [CrossRef]

- Binns, D.; Dimmer, E.; Huntley, R.; Barrell, D.; O’donovan, C.; Apweiler, R. QuickGO: a web-based tool for Gene Ontology searching. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 3045-3046. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.-L., Park, C.A., & Reecy, J.M. Bringing the Animal QTLdb and CorrDB into the future: meeting new challenges and providing updated services. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D956–D961. [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, N.H.; Karaşahin, T.; Dursun, Ş.; Akbulut, N.K.; Haydardedeoğlu, A.E.; Ilgün, R.; Büyükleblebici, O. Comparative investigation of some liver enzyme functions considering age and gender distinctions in healthy Akkaraman sheep. JECM 2018, 35, 71-75.

- de Souza, T.C.; de Souza, T.C.; Rovadoscki, G.A.; Coutinho, L.L.; Mourao, G.B.; de Camargo, G.M.F.; Pinto, L.F.B. Genome-wide association for plasma urea concentration in sheep. Livest Sci, 2021, 248, 104483. [CrossRef]

- Luke, T. D. W., Rochfort, S., Wales, W. J., Bonfatti, V., Marett, L., & Pryce, J. E. Metabolic profiling of early-lactation dairy cows using milk mid-infrared spectra. J Dairy Sci, 2019, 102, 1747-1760. [CrossRef]

- Schade, D.S.; Shey, L.; Eaton, R.P. Cholesterol review: a metabolically important molecule. Endocr Pract 2020, 26, 1514-1523. [CrossRef]

- Machnicka, B.; Grochowalska, R.; Bogusławska, D. M.; Sikorski, A.F. The role of spectrin in cell adhesion and cell–cell contact. Expl Biol Med, 2019, 244, 1303-1312. [CrossRef]

- Iacono, J.M.; Ammerman, C.B. The effect of calcium in maintaining normal levels of serum cholesterol and phospholipids in rabbits during acute starvation. Am J Clin Nutr 1966, 18, 197-202. [CrossRef]

- Suica, V.I.; Uyy, E.; Boteanu, R.M.; Ivan, L.; Antohe, F. Alteration of actin dependent signaling pathways associated with membrane microdomains in hyperlipidemia. Proteome Sci, 2015, 13, 30. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Li, D. Spectrin: structure, function and disease. Sci China Life Sci, 2013, 56, 1076-1085. [CrossRef]

- Blake, J.A.; Baldarelli, R.; Kadin, J.A.; Richardson, J.E.; Smith, C.L.; Bult, C.J.; Mouse Genome Database Group. Mouse Genome Database (MGD): Knowledgebase for mouse-human comparative biology. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, 981-987. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, P.J.; Morgenstern, R.; Mancini, J.; Ford-Hutchinson, A.; Persson, B. Common structural features of MAPEG—a widespread superfamily of membrane associated proteins with highly divergent functions in eicosanoid and glutathione metabolism. Prot Sci 1999, 8, 689-692. [CrossRef]

- Dennis, E.A.; Norris, P.C. Eicosanoid storm in infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2015, 15, 8:511-23. [CrossRef]

- Iovannisci, D.M.; Lammer, E.J.; Steiner, L.; Cheng, S.; Mahoney, L.T.; Davis, P.H.; Lauer, R.M.; Burns, T.L. Association between a leukotriene C4 synthase gene promoter polymorphism and coronary artery calcium in young women: the Muscatine Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007, 27, 2:394-9. [CrossRef]

- Onopiuk, A.; Tokarzewicz, A.; Gorodkiewicz, E. Cystatin C: a kidney function biomarker. Adv Clin Chem 2015, 68, 57-69. [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, Y.; Pippin, J.W.; Hagmann, H.; Krofft, R.D.; Chang, A.M.; Zhang, J.; Terada, Y.; Brinkkoetter, P.; Shankland, S.J. Both cyclin I and p35 are required for maximal survival benefit of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 in kidney podocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2012, 302, F1161-F1171. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Balbo, B.; Ma, M.; Zhao, J.; Tian, X.; Kluger, Y.; Somlo, S. Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 activity is a driver of cyst growth in polycystic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol, 2021, 32, 41-51. [CrossRef]

- Saurus, P.; Kuusela, S.; Dumont, V.; Lehtonen, E.; Fogarty, C.L.; Lassenius, M.I.; Forsblom, C.; Lehto, M.; Saleem, M.A.; Groop, P.H.; Lehtonen, S. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 protects podocytes from apoptosis. Sci Rep, 2016, 6, 21664. [CrossRef]

- van Buul-Offers, S.C.; Kooijman, R. The role of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factors in the immune system. Cell Mol Life Sci 1998, 54, 1083-1094. [CrossRef]

- Alzaid, A.; Castro, R.; Wang, T.; Secombes, C.J.; Boudinot, P.; Macqueen, D.J.; Martin, S.A. Cross talk between growth and immunity: coupling of the IGF axis to conserved cytokine pathways in rainbow trout. Endocrinology, 2016, 157, 1942-1955. [CrossRef]

- Liso, A.; Venuto, S.; Coda, A.R.D.; Giallongo, C.; Palumbo, G.A.; Tibullo, D. IGFBP-6: at the crossroads of immunity, tissue repair and fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 23, 4358. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Smyth, D.; Al-Khalaf, M.; Blet, A.; Du, Q.; Bernick, J.; Gong, M.; Chi, X.; Oh, Y.; Roba-Oshin, M.; Coletta, E. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-7 (IGFBP7) links senescence to heart failure. Nat Cardiovasc Res 2022, 1, 1195-1214. [CrossRef]

- Sonnewald, U.; Wang, A.Y.; Schousboe, A.; Erikson, R.; Skottner, A. New aspects of lactate metabolism: IGF-I and insulin regulate mitochondrial function in cultured brain cells during normoxia and hypoxia. Dev Neurosci 1996, 18, 443-448. [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, A. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) signaling in glucose metabolism in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 6434. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M. L. Role of transporters in regulating mammalian intracellular inorganic phosphate. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1163442. [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.B.; Liu, C.Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.P.; Xiong, Y.; Lei, Q.Y.; Guan, K.L. PARD 3 induces TAZ activation and cell growth by promoting LATS 1 and PP 1 interaction. EMBO Rep 2015, 16, 975-985. [CrossRef]

- Piroli, M.E.; Blanchette, J.O.; Jabbarzadeh, E. Polarity as a physiological modulator of cell function. Front Biosci (Landmark edition) 2019, 24, 451. [CrossRef]

- Bryant, D.M.; Mostov, K.E. From cells to organs: building polarized tissue. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio, 2008, 9, 887-901. [CrossRef]

- Orlando, K.; Guo, W. Membrane organization and dynamics in cell polarity. ColdSpring Harb Perspect Biol 2009, 1, a001321. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).