Submitted:

21 June 2024

Posted:

24 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

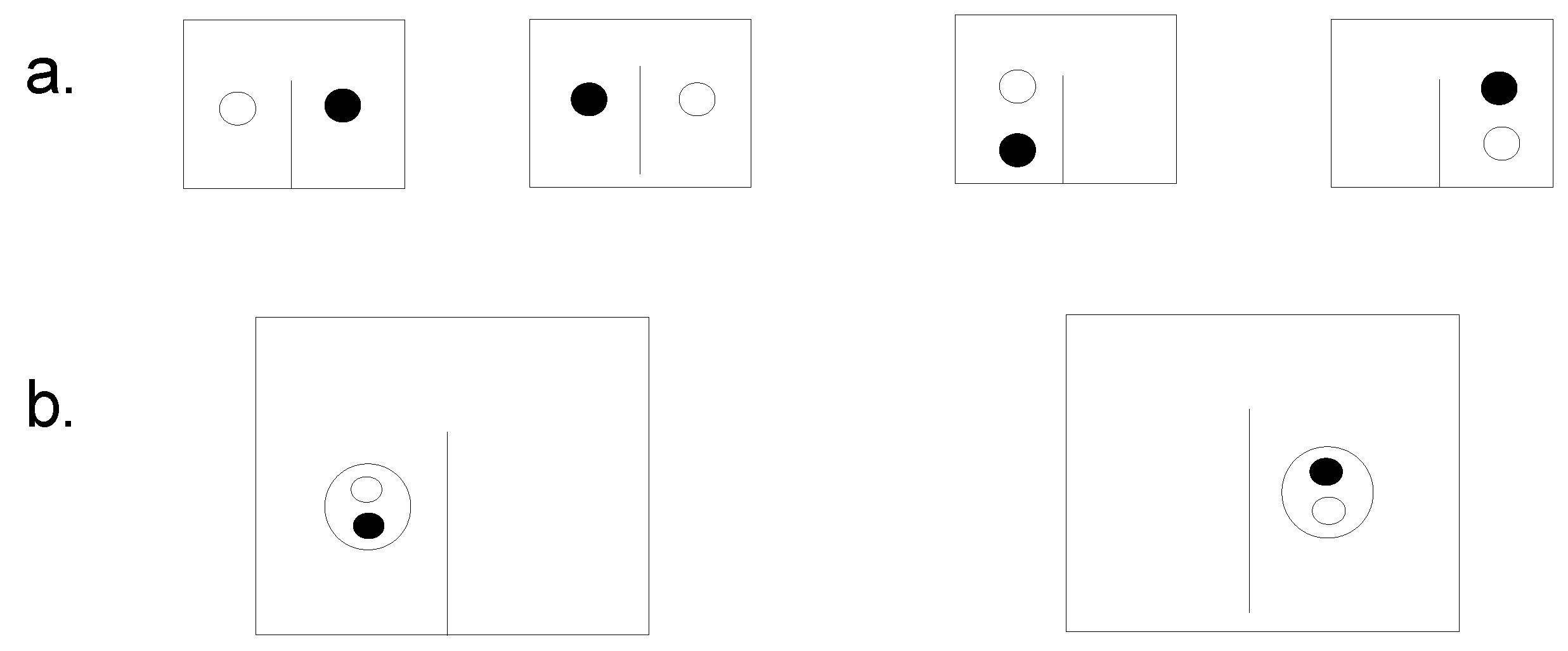

2. The Structure of the Module Arises from Information

3. Module as an Intelligent Agent or Decision-Maker

- -

- Self-organization is the process of evaluating the probabilities of states in a system in search of a more thermodynamically stable state.

- -

- Decision-making is the process of evaluating alternatives (states) of decision-making in search of the most stable preferential alternative.

4. Modules Are Real Demons: Definition of Information

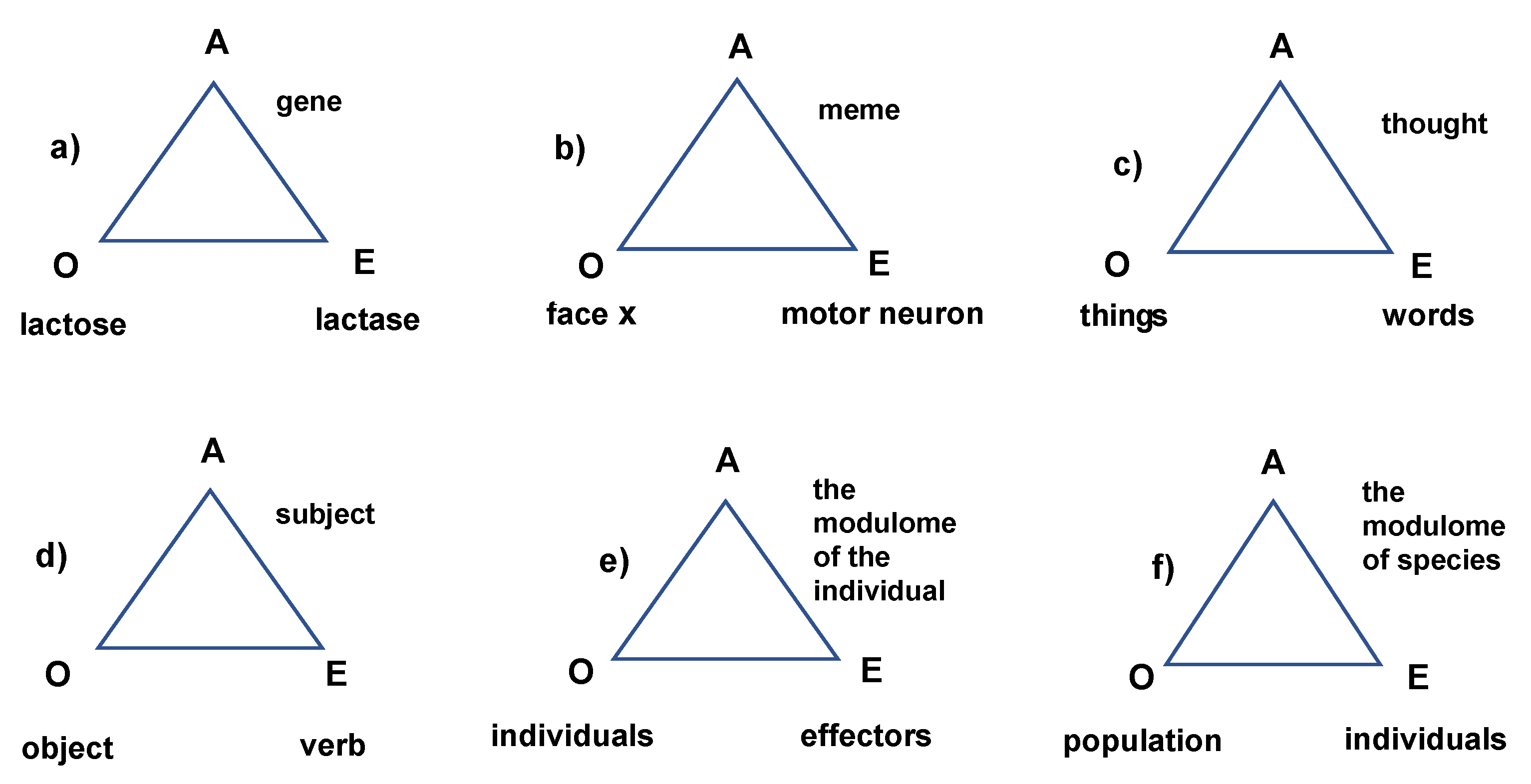

5. Modular Thinking and Modular Biology

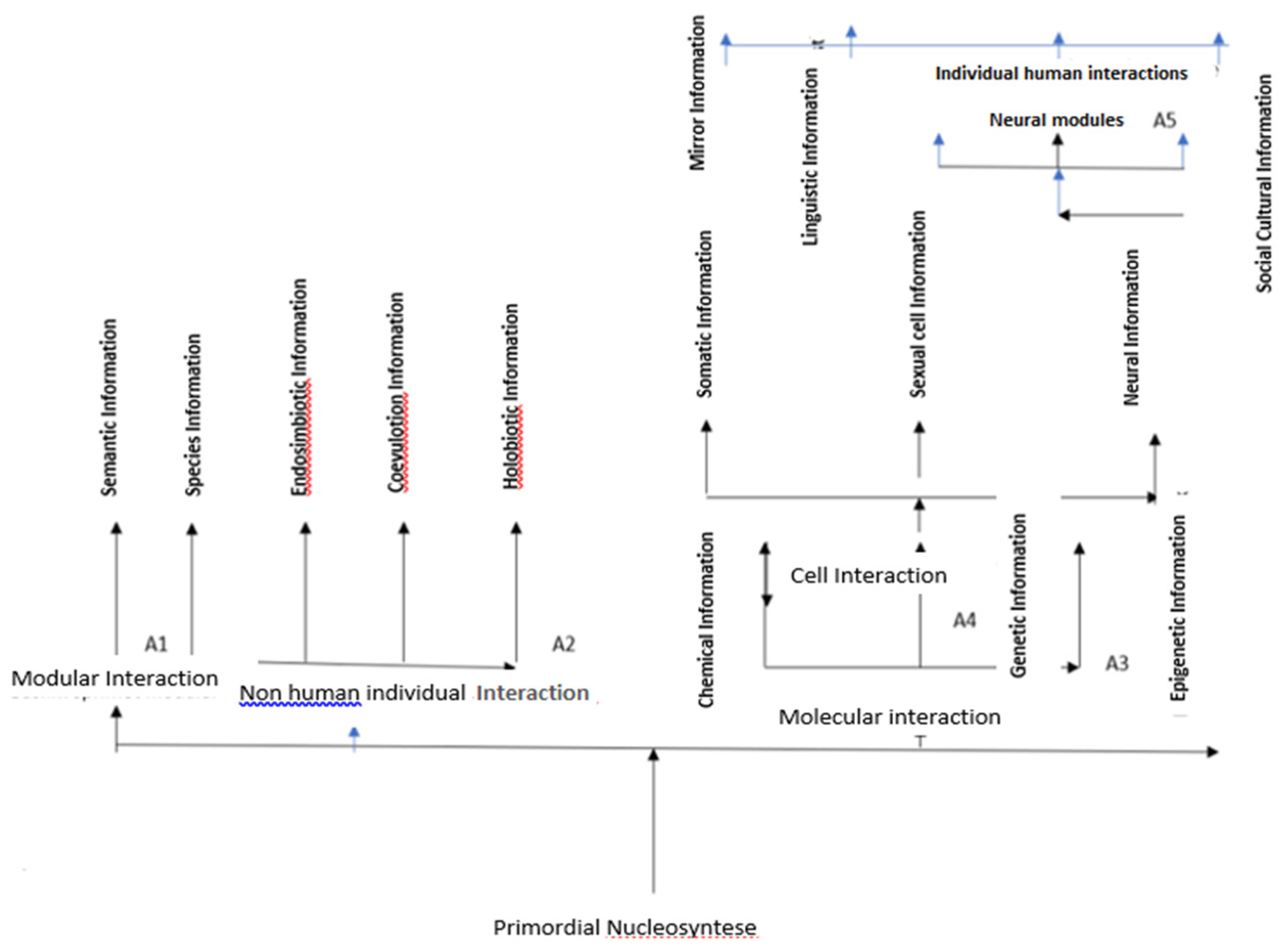

6. The Tree of Life Is Based on the Formats of Interaction Information

7. The Model of Modular Evolution

7.1. Module Description

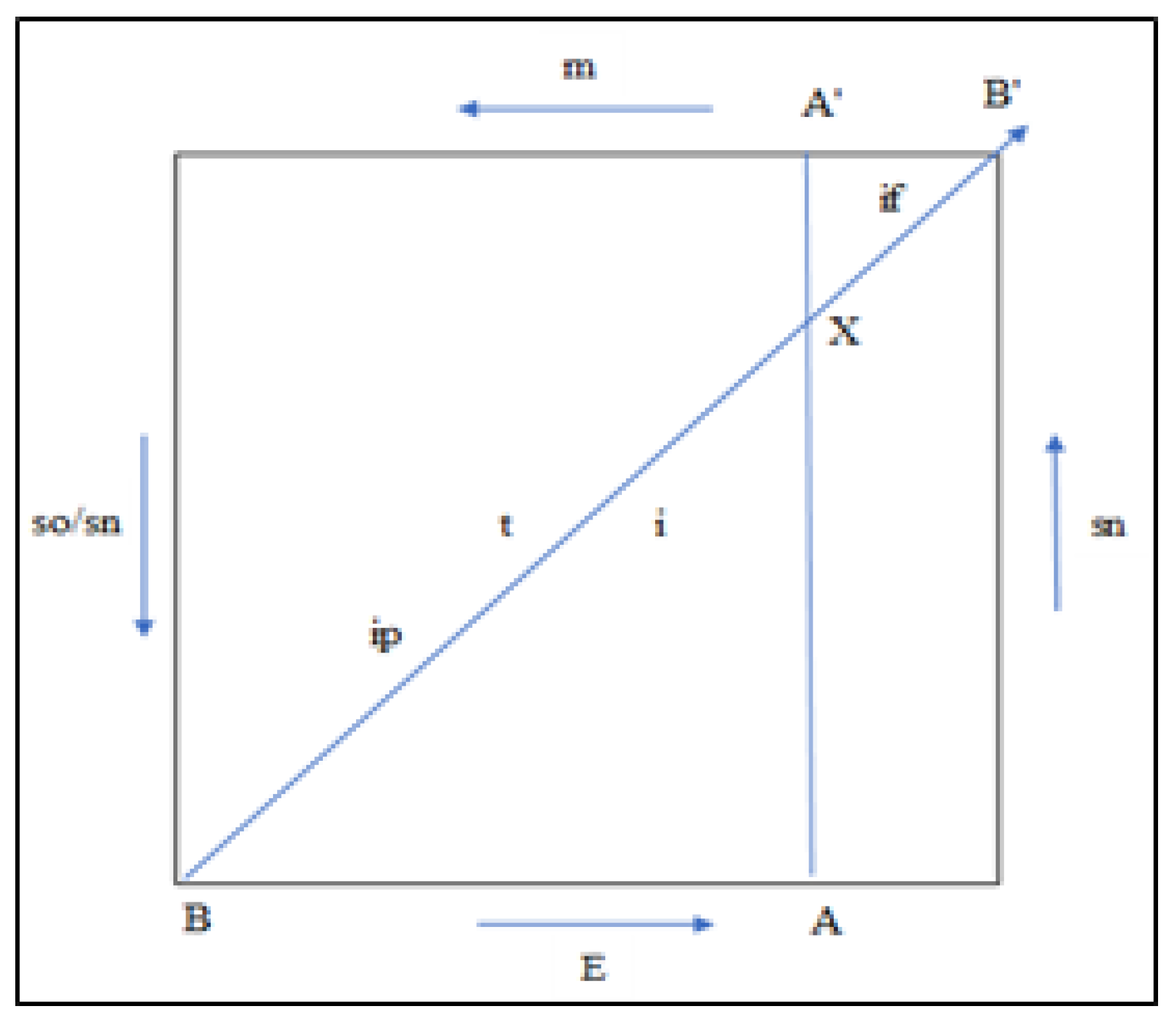

7.2. Information Is Not Matter But One of Its Properties

7.3. Evolutionary Factors: e = m∙i

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bajrami, Z.; Rrokaj, S. Modular Evolution: A Hypothesis for Language Acquisition. International Journal of Language and Linguistic 2023, 10, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bajrami, Z. Informacioni dhe evolucioni modular; Akademia e Shkencave të Shqipërisë: Tiranë, 2024; ISBN 9789928809193. [Google Scholar]

- Spirkin, A.G. Dialectical Materialism; Progress Publishers: Moscow, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Landauer, R. Information Is Physical. Physics Today 1991, 44, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, R. Information Is a Physical Entity. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 1999, 263, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingers, J. Information and Meaning: Foundations for an Intersubjective Account. Information Systems Journal 1995, 5, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonier, T. Information as a Basic Property of the Universe. Biosystems 1996, 38, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehn, J.-M. Toward Complex Matter: Supramolecular Chemistry and Self-Organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 4763–4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabej, N.R. On the Origin and Nature of Nongenetic Information in Eumetazoans. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2023, 1525, 104–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershenson, C.; Fernández, N. Complexity and Information: Measuring Emergence, Self-Organization, and Homeostasis at Multiple Scales. Complexity 2012, 18, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, C. The Evolution of Biological Information: How Evolution Creates Complexity, from Viruses to Brains; Princeton University Press; ISBN 978-0-691-24115-9.

- Haken, H.; Portugali, J. Information and Self-Organization. Entropy 2017, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szathmáry, E.; Smith, J.M. The Major Evolutionary Transitions. Nature 1995, 374, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovalenko, T.; Vincent, S.; Yukalov, V.I.; Sornette, D. Calibration of Quantum Decision Theory: Aversion to Large Losses and Predictability of Probabilistic Choices. J. Phys. Complex. 2023, 4, 015009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajrami, Z. The Modular Concept of Gene. Journal of Natural Sciences Research 2013, 3, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding; Revised edition.; Shambhala: Boston, 1992; ISBN 978-0-87773-642-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, M. Constructing a Language: A Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition; First Edition.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Mass, 2005; ISBN 978-0-674-01764-1. [Google Scholar]

- Von Bertalanffy, L. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications (Revised Edition) by Ludwig Von Bertalanffy: New Paperback (1969) | GoldenWavesOfBooks. Available online: https://www.abebooks.com/9780807604533/General-System-Theory-Foundations-Development-0807604534/plp (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Sugita, M.; Onishi, I.; Irisa, M.; Yoshida, N.; Hirata, F. Molecular Recognition and Self-Organization in Life Phenomena Studied by a Statistical Mechanics of Molecular Liquids, the RISM/3D-RISM Theory. Molecules 2021, 26, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modularity in Development and Evolution; Schlosser, G. , Wagner, G.P., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 2004; ISBN 978-0-226-73853-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins, R. The Selfish Gene: 40th Anniversary Edition; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2016; ISBN 978-0-19-878860-7. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, G.P. Homologues, Natural Kinds and the Evolution of Modularity. Amer Zool 1996, 36, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, G.P.; Lynch, V.J. Evolutionary Novelties. Curr Biol 2010, 20, R48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haken, H. Information and Self-Organization: A Macroscopic Approach to Complex Systems; Softcover reprint of hardcover 3rd ed. 2006 edition; Springer: Berlin, 2010; ISBN 978-3-642-06957-4. [Google Scholar]

- Self-Organization in Biological Systems; Camazine, S., Ed.; Princeton studies in complexity; 2. print., and 1. paperback print.; Princeton Univ. Press: Princeton, NJ, 2003; ISBN 978-0-691-11624-2. ISBN 978-0-691-11624-2.

- Yukalov, V.I.; Sornette, D. Self-Organization in Complex Systems as Decision Making. Advs. Complex Syst. 2014, 17, 1450016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forterre, P.I.P. Darwin’s Goldmine Is Still Open: Variation and Selection Run the World. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauffman, S.A. The Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution; 1st edition.; Oxford University Press: New York, 1993; ISBN 978-0-19-507951-7. [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger, E. What Is Life? & Mind and Matter: The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell; Cambridge University Press, 1974.

- Alemi, M. Life, Energy and Information. In The Amazing Journey of Reason; SpringerBriefs in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-3-030-25961-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lherminier, P. La prédation informative : vers un nouveau concept d’espèce. Comptes Rendus. Biologies 2018, 341, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind; University of Chicago Press ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 2000; ISBN 978-0-226-03906-0.

- Shanon, C. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. 27, 379–423.

- Ernst Mayr Evolution and Anthropology: A Centennial Appraisal.; Washington, 1959.

- O’hara, R.J. Population Thinking and Tree Thinking in Systematics. Zoologica Scripta 1997, 26, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N. January 18 2023.

- N, E.; Craik, K.J.W. The Nature of Explanation. Journal of Philosophy 1943, 40, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, C. The Use of Information Theory in Evolutionary Biology. 2012, 1256, 49–65. [CrossRef]

- Harari, Y.N. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind; Illustrated edition.; Harper: New York, NY, 2015; ISBN 978-0-06-231609-7. [Google Scholar]

- Vetsigian, K.; Woese, C.; Goldenfeld, N. Collective Evolution and the Genetic Code. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 10696–10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Fabbri-Destro, M.; Cattaneo, L. Mirror Neurons and Their Clinical Relevance. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 2009, 5, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, M. From Biosemiotics to Code Biology. Biol Theory 2014, 9, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzany, G. Plant Communication from Biosemiotic Perspective: Differences in Abiotic and Biotic Signal Perception Determine Content Arrangement of Response Behavior. Context Determines Meaning of Meta-, Inter- and Intraorganismic Plant Signaling. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2006, 1, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vopson, M.M. The Mass-Energy-Information Equivalence Principle. AIP Advances 2019, 9, 095206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vopson, M.M. Experimental Protocol for Testing the Mass–Energy–Information Equivalence Principle. AIP Advances 2022, 12, 035311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A. A Proposed Experimental Test for the Mass-Energy-Information Equivalence Principle. Scilight 2022, 2022, 091111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.L.; Cleland, C.E.; Arend, D.; Bartlett, S.; Cleaves, H.J.; Demarest, H.; Prabhu, A.; Lunine, J.I.; Hazen, R.M. On the Roles of Function and Selection in Evolving Systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023, 120, e2310223120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerkandl, E.; Pauling, L. Molecules as Documents of Evolutionary History. J Theor Biol 1965, 8, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapicque, L. L’excitabilité En Fonction Du Temps : La Chronaxie, Sa Signification et Sa Mesure Par Louis Lapicque. 1926; Generic, 2022.

- Pol, A. Life: Energy-Information Relationship within Materials Systems: General Outline of the Concept T. Computers Math. Applic. 1990, 20, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontzer, H.; Brown, M.H.; Raichlen, D.A.; Dunsworth, H.; Hare, B.; Walker, K.; Luke, A.; Dugas, L.R.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.; Schoeller, D.; et al. Metabolic Acceleration and the Evolution of Human Brain Size and Life History. Nature 2016, 533, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layer, P.G. Brains Emerging: On Modularity and Self-Organisation of Neural Development In Vivo and In Vitro. In Emergence and Modularity in Life Sciences; Wegner, L.H., Lüttge, U., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 145–169. ISBN 978-3-030-06128-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; McShea, D. Operationalizing Goal Directedness; An Empirical Route to Advancing a Philosophical Discussion. 2020, 12.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).