Case report

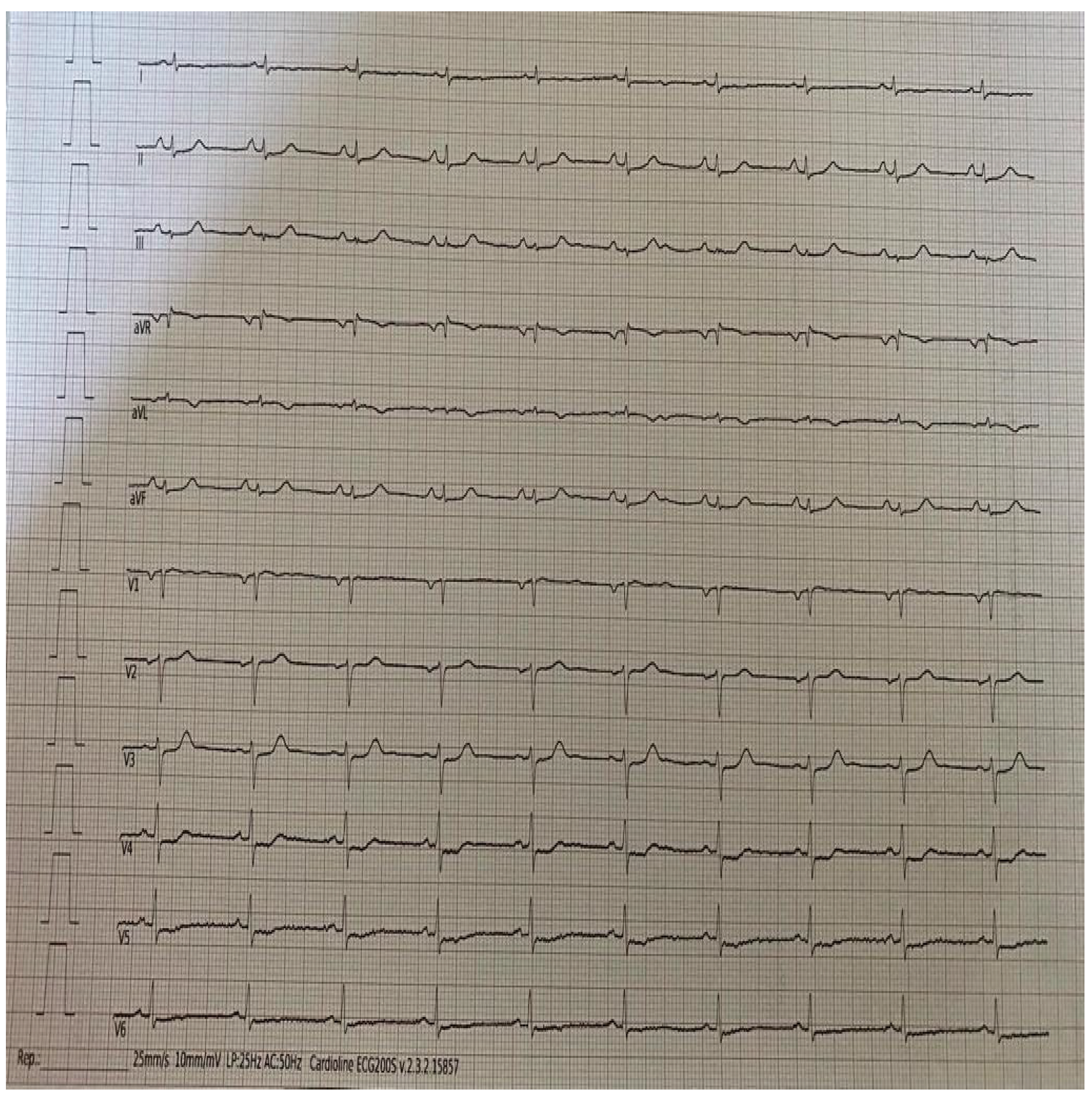

A 68-year-old patient with a history of dyslipidemia and previous anterior STEMI (2021), complicated by cardiovascular arrest, treated with primary angioplasty and implantation of 2 stents on the middle section of the anterior descending artery at the origin of the first diagonal branch. In May 2023 he accessed the outpatient clinics of our hospital for a random checkup, and reported reporting over the past few months appearance of atypical angor unrelated to exertion and spontaneous regression; on ECG finding of rigid ST-segment elevation at the antero-lateral site (

Figure 1).

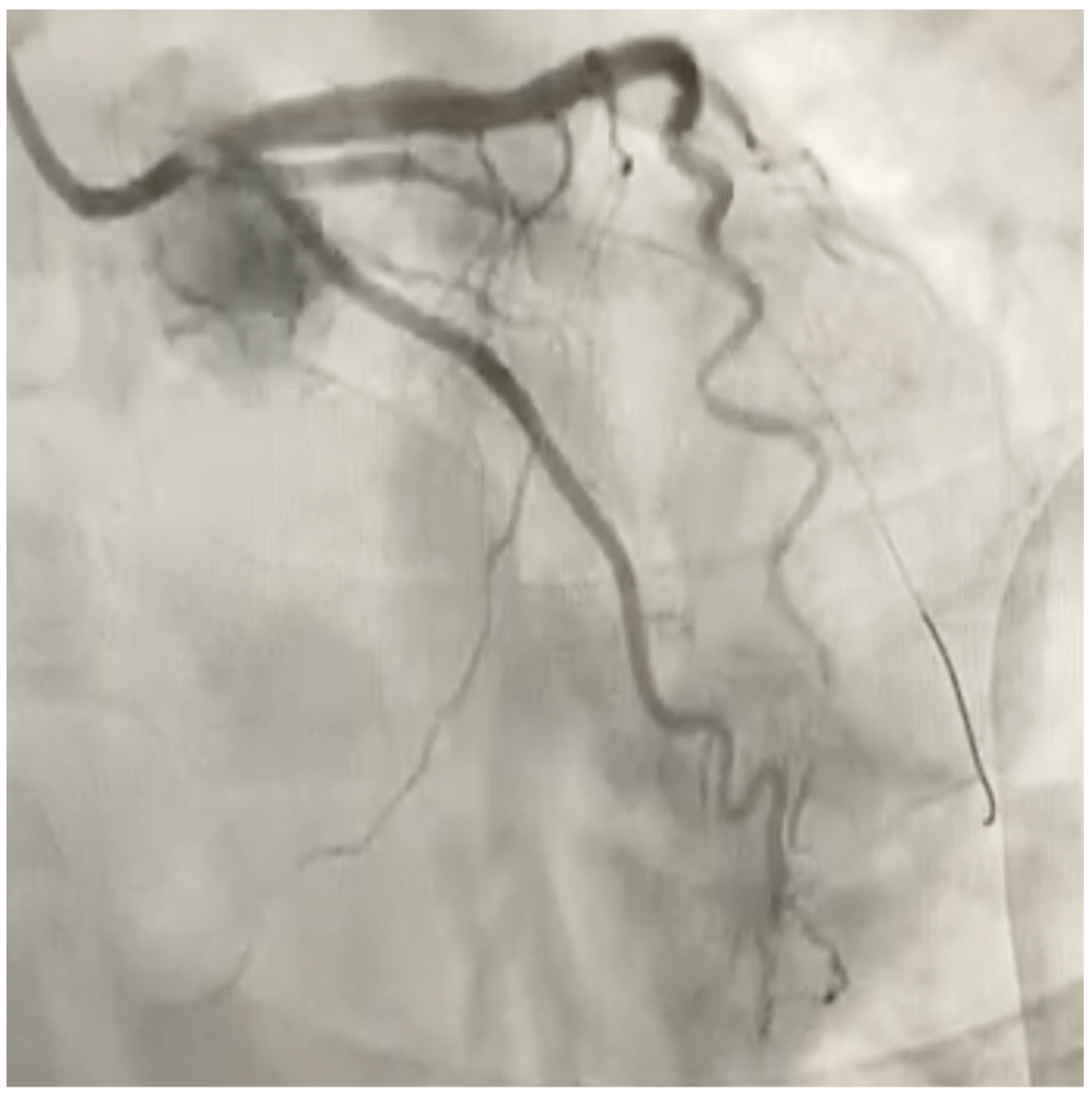

Therefore, he was sent to the emergency department of our hospital where hematochemical examinations were performed documenting increased indices of myocardiocytosis (in particular troponin I hs of 3492 ng/L). Post diagnosis of NSTEMI, the patient was taken to the hemodynamics room and underwent coronary study documenting subocclusion of the first marginal branch (figure, treated with medicated balloon (

Figure 2). During hospitalization, color-doppler echocardiogram was performed documenting hypokinesis of the SIV and apex proper, preserved global systolic function (FE 55%), grade I diastolic dysfunction (E/A 0,8), mild mitral insufficiency and mild tricuspid insufficiency.

Home therapy included: pantoprazole 40 mg 1 cp/day, bisoprolol 1,25 mg 1 cp/day, ticagrelor 90 mg 1 cp/bid, cardioaspirin 100 mg 1 cp/day, rosuvastatin/ezetimibe 20/10 mg 1 cp/day; optimized then by switching to bisoprolol 1,25 mg 1 cp/bid and adding ranolazine 375 mg/bid in therapy.

During hospitalization, the following examinations were performed: lipid profile (triglycerides 70 mg/dl, total cholesterol 92 mg/dl, LDL 40 mg/dl, HDL 37 mg/dl), lipoprotein a (Lpa) 24,9 mg/dl (normal values: < 30 mg/dl), homocysteine 12,20 mmol/l (normal values: 5,4-16,2 mmol/l), special coagulation: factor V 52% (normal values: 80-120%), activated protein C-V Leiden resistance test 287 sec (normal values > 120 sec), antithrombin III 73% (normal values: 80-120%), functional protein C 76% (normal values: 65-145%), functional protein S 94% (normal values: 74-146%), fibrinogenemia 400 mg/dl (normal values: 200-400 mg/dl), genetic tests (absence of factor V Leiden and factor II polymorphisms).

Discussion

The clinical case under consideration is paradoxical: it concerns a subject with good control of cardiovascular risk factors who, about a year later, has a new cardiovascular event. In addition to the double antiplatelet therapy he has been taking as per the guidelines for a year, he also takes rosuvastatin combined with ezetimibe, maintaining LDL values of 40 mg/dl. This value allows a further consideration to be made, as it is the therapeutic target to be pursued in coronary artery disease subjects who have had a new cardiovascular event within two years of the last one (for which the patient has a lipid profile that is perfectly normal).

The subject does not have a hypercoagulable state (fibrinogenemia within normal limits and no mutations for Leiden factor V) and homocysteine values are also within normal limits.

During the hospital stay, we further investigated the risk profile by also assessing lipoprotein a, a lipoprotein synthesised by the liver, whose plasma concentrations are genetically determined.

There is great interindividual variability with values ranging from <1 to >200 mg/dL in the general population; indeed, individuals of African ethnicity have higher concentrations on average than individuals of European or Asian origin [

1].

High concentrations of lipoprotein a have long been correlated with an increased risk of acute coronary syndrome [1, 2]; moreover, studies in vitro and in animal models have shown that this lipoprotein plays a key role in atherosclerosis, particularly in promoting the formation of foam cells, promoting smooth muscle cell proliferation, inflammation and contributing to plaque instability [3, 4]. Among other things, lipoprotein a has been identified as the main carrier of oxidised phospholipids, which are considered proinflammatory and proatherogenic factors [

5].

Conclusion

The clinical case reported by us confirms that some patients, despite careful control of risk factors, target LDL-C and optimised drug treatment, have a high residual risk of CV events. In these patients it is likely that LDL-C targets need to be even more stringent, probably, as some literature data already show, below those currently recommended by the guidelines.

Contribution

Acknowledgement that all authors have contributed significantly and that all authors agree with the content of the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Availability of data and materials

All data underlying the findings are fully available.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical committee approval was required for this case report by the Department, because this article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals. Informed consent was obtained from the patient included in this study.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements should include contributions from anyone who does not meet the criteria for authorship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that no conflict of interest.

Consent for publication

The patient gave his written consent to use his personal data for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

References

- Utermann G. Lipoprotein(a). Metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. Ed, Mc-Graw-Hill, New York: Medical Publishing Division 2006; 2753–87.

- Kamstrup PR. Lipoprotein(a) and ischemic heart disease– a causal association? A review. Atherosclerosis 2010; 211:15–23. [CrossRef]

- Boffa MB, Marcovina SM, Koschinsky ML. Lipoprotein(a) as a risk factor for atherosclerosis and thrombosis: mechanistic insights from animal models. Clin Biochem 2004; 37:333–43. [CrossRef]

- Deb A, Caplice NM. Lipoprotein(a): new insights into mechanisms of atherogenesis and thrombosis. Clin Cardiol 2004; 27:258–64. [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas S, Brilakis ES, Miller ER, et al. Oxidized phospholipids, Lp(a) lipoprotein, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:46–57. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).