1. Introduction

ChatGPT, an advanced AI Large Language Model (LLM) technology, was launched by the American artificial intelligence research lab OpenAI at the end of November 2022 [

1]. Through extensive data training, ChatGPT assists in analyzing medical records [

2], providing psychological health support [

3], and aiding medical research in the field of medicine [

4]. This technology is reshaping our medical practices, sparking a new revolution in healthcare [

5]. In March 2023, OpenAI released ChatGPT-4, a more human-like general AI than its predecessor, ChatGPT-3.5 [

1]. It demonstrates superior performance in understanding, reasoning, and responding to complex questions. By September 2023, OpenAI updated ChatGPT to perform internet searches through Microsoft’s Bing search engine, breaking free from the data limitations of September 2021 [

6].

In the medical field, ChatGPT-4, through its deep learning and natural language processing capabilities, has passed the three-stage United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) [

7]. This marks a significant milestone in the maturity of AI in healthcare. It can assist medical professionals in handling a vast amount of medical literature [

8], clinical records, insurance documents, and patient inquiries [

9]. ChatGPT-4 can provide information on clinical trials relevant to patient needs [

2], assist doctors in quickly accessing information on related cases, and offer suggestions based on the latest medical education and research [

10], thereby enhancing work efficiency and the accuracy of information processing.

In the field of cancer, ChatGPT-4 can assist in patient education for cancer patients, analysis of next-generation genetic data in cancer (NGS) [

2], care recommendations for patients with hepatitis and cirrhosis [

11], clarifying common cancer myths [

12,

13], and answering health-related questions on social media [

3]. While ChatGPT-4 provides professional and accurate responses, and its conversational manner is warm, empathetic [

3], and patient, it is not yet able to provide complete and correct guidance for cancer treatment [

13,

14].

In modern cancer care, the increasing application of Electronic Patient-Reported Outcomes (ePROs) underscores their importance in enhancing patient care quality and treatment effectiveness [

15,

16]. EPROs allow patients to report their health status, symptoms, and quality of life through digital platforms, providing valuable firsthand data for medical teams [

17]. This approach not only helps physicians understand and manage symptoms more precisely but also gives patients a greater sense of participation and control during treatment [

18].

Increasing research shows that the care model of Electronic Patient-Reported Outcomes (ePROs) provides patient data that can be increasingly integrated into clinical decision support tools [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. This aids healthcare professionals in timely identifying and addressing potential health issues, thereby preventing disease progression or mitigating side effects. Recent ePROs research can help patients improve treatment tolerance, survival rates, enhance communication and interaction between doctors and patients, reduce unnecessary emergency department visits and hospitalizations [

16], and decrease medical expenses, leading to better cost-effectiveness [

23].Additionally, the accumulation of ePROs data offers a rich resource for clinical research, contributing to improved future cancer treatment strategies and patient care models [

24].It also helps reduce carbon emissions, aiding hospital ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) transformation [

23,

25], and provides better cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic [

15].

However, ePROs generate vast amounts of electronic symptom data from patients, necessitating additional nurses and time for interpretation, analysis, and further generation of clinical decision-making processes for symptom management [

19,

21]. This may include consulting with dietitians for issues such as weight loss, for instance, determining whether a patient’s continuous deterioration from diarrhea warrants a telephone reminder for an early return to the hospital for examination, and requires further health education from a dietitian.

In a medical environment characterized by a shortage of oncology staff and overworked healthcare personnel [

26,

27], integrating the use of ChatGPT-4 to analyze medical data, drive medical innovation, aid with patient discharge notes and provide educational functions may alleviate the burden on the healthcare team in patient care [

2,

4,

9,

10,

28].

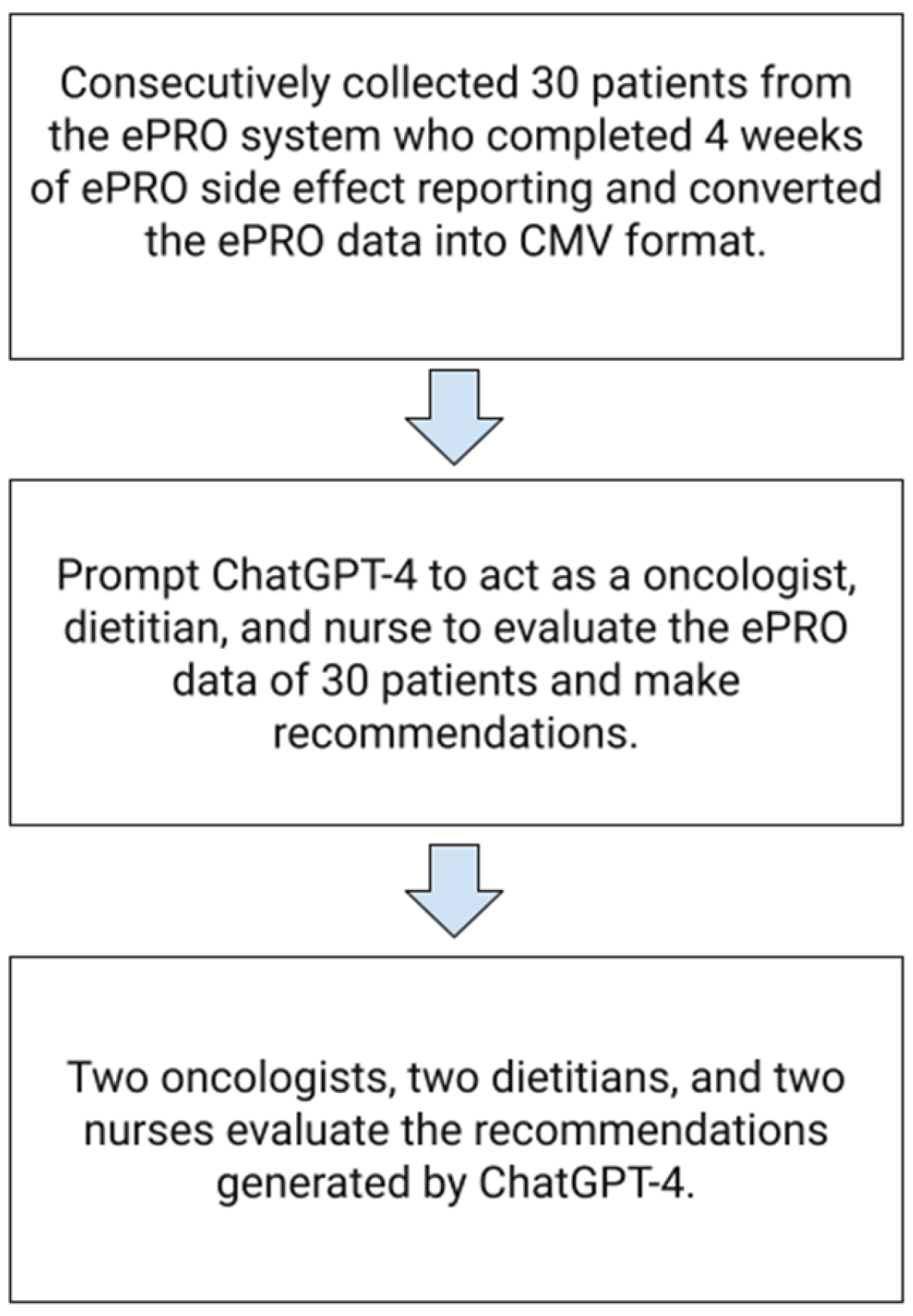

We conducted a pilot study using ChatGPT-4 to analyze ePROs data on patient side effects. ChatGPT-4 simulated different medical team roles, attempting to analyze and provide improvement suggestions for side effect data across various cancer types, ages, and treatment methods. The medical team evaluated the feasibility of integrating ChatGPT-4’s analysis responses into clinical care decisions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

We utilize a web-based electronic patient report outcome system (developed by Cancell Tech Co. Ltd., Taiwan, available at [

https://cancell.tw]), which was launched in January 2023 for use by cancer patients. Each patient can create their own account with a password, agree to the terms of use for clinical study by signing a consent form, and then log in to use the system. Patients are required to fill in basic information such as name, gender, age, type of cancer, stage, and current treatment. During their treatment, patients subjectively report symptoms of side effects twice a week using the electronic patient report outcome system, which incorporates common cancer side effects as defined by NCI/ASCO. The data recorded by the patients include quantifiable metrics such as weight and body temperature; scores for quality of life and mood on a scale from 1 to 5, where higher scores indicate better states; pain scores also ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more severe pain. Symptoms such as reduced appetite, stomach discomfort, diarrhea, constipation, nausea and vomiting, coughing, shortness of breath, fatigue, depression, and insomnia are rated on a four-point scale: 0 for no symptoms, 1 for mild, 2 for moderate, and 3 for severe symptoms, covering a total of 15 symptom items. The data is stored on AWS cloud storage, with firewalls and other cybersecurity measures in place for data protection.

To gain an initial understanding of the ePRO data analysis for different cancer types, we consecutively collected 30 patients who had completed the ePRO side effect datas at least 4 weeks from January 2023 to June 2023. We de-linked and de-identified the basic information of these patients, retaining only their age, type of cancer, gender, stage, and treatment method, along with the ePRO side effect symptom data, for further analysis by ChatGPT-4.

Among the 30 de-identified patients, one example of ePRO side effect data during treatment for nasopharyngeal cancer is shown in

Table 1. We formatted the ePRO side effect data using the CMV file format and initiated new conversations in ChatGPT-4 on the website

https://chat.openai.com. For each new conversation, we requested ChatGPT-4 to assume the roles of an oncologist, a dietitian, and a nurse respectively to analyze the changes in 4 weeks ePRO side effect data for these 30 patients undergoing cancer treatment, providing analysis and improvement suggestions. The prompt used was as follows: “Please role-play as an oncologist (or a dietitian, or a nurse) to analyze the changes in this cancer patient’s electronic patient report outcome side effect data, and provide detailed recommendations for improvement in Traditional Chinese. Thank you.” We then collected 90 sets of responses generated by ChatGPT-4 (each patient received 3 sets of expert simulations by ChatGPT-4, totaling 90 sets of recommendations for the 30 patients. ChatGPT-4 recommendation example in supplement).

2.2. Evaluation Criteria

Thirty patients received a total of 90 sets of recommendations generated by ChatGPT-4. These recommendations were then evaluated by a senior medical team comprising 2 oncologists, 2 oncology dietitians, and 2 oncology nurses, resulting in 180, 180, and 180 assessment records, respectively. The medical team assessed the replies from ChatGPT-4 based on several criteria: completeness of the response, accuracy of the content, potential harm to the patient, empathy in the reply, emotional support provided, improvement in patient communication efficiency, the usefulness of ChatGPT-4 in reducing the burden of medical care if used cautiously, and the enhancement of patient disease health literacy. The evaluations were scored on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 representing very poor or minimal and 10 representing excellent. Finally, the assessments identified which professional role’s response from ChatGPT-4 was the best, covering nine aspects of evaluation. This study workflow is showed in

Figure 1.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of China Medical University & Hospital,Taichung,Taiwan(No.:ePRO_HN_001/CMUH112-REC2-128(AR-1)).

3. Results

Among the 30 consecutively selected cancer patients, there were 8 cases of breast cancer, 7 cases of head and neck cancer, 3 cases of lung cancer, and 2 cases each of prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer, lymphoma, renal cell carcinoma, uterine sarcoma, and endometrial cancer. In terms of cancer stages, there were 5 cases of stage I, 7 cases of stage II, 8 cases of stage III, and 10 cases of stage IV. The median age was 55 years. Regarding treatment methods, 12 patients received chemotherapy, 8 underwent concurrent chemoradiotherapy, 5 had radiotherapy, and 5 were given targeted therapy. There were 11 male patients and 19 female patients. The patients’ characteristics are in

Table 2.

The two oncologists evaluating GPT included a radiation oncologist, a hematologist-oncologist. Additionally, two oncologists, two oncology nutritionists, and two oncology nurses assessed GPT-4.0’s simulated performance in three roles for the treatment of 30 patients, generating 180, 180, and 180 evaluations, respectively.

When ChatGPT-4.0 acted as an oncologist analyzing the ePRO data of 30 patients, the average scores were as follows:completeness: 8.1 (range 7-10), accuracy: 8.2 (range 7-9), potential harm to the patient: 1.2 (range 0-3), empathetic response: 7.9 (range 6-10), emotional support: 7.6 (range 6-9), improvement in patient communication efficiency: 8 (range 7-9), reduction in medical care stress: 7.9 (range 6-10), and increase in health literacy: 8.1 (range 7-10).The scores are in

Table 3.

When ChatGPT-4.0 acted as an oncology dietitian analyzing the ePRO data of 30 patients, the average scores were as follows: completeness: 8.4 (range 6-9), accuracy: 8.1 (range 5-9), potential harm to the patient: 1.1 (range 1-3), empathetic response:7.6 (range 6-9), emotional support: 7.5 (range 6-9), improvement in patient communication efficiency: 8.4 (range 5-9), reduction in medical care stress: 8.2 (range 5-9), and increase in health literacy: 8.3 (range 6-10).The scores are in

Table 4.

When ChatGPT-4.0 acted as an oncology nurse analyzing the ePRO data of 30 patients, the average scores were as follows: completeness: 8 (range 6-9), accuracy: 8.2 (range 7-9), potential harm to the patient: 0.9 (range 0-2), empathetic response: 7.7 (range 5-9), emotional support: 7.5 (range 7-8), improvement in patient communication efficiency: 8.3 (range 7-9), reduction in medical care stress: 8.1 (range 6-9), and increase in health literacy: 8.2 (range 5-9).The scores are in

Table 5.

ChatGPT 4.0, acting as an oncologist, dietitian, and nurse, received a sum of the average scores of 54.6, 55.4, and 55.1 respectively for analyzing the ePRO data of 30 patients. ChatGPT 4.0 received the highest score in the role of an oncology dietitian.

4. Discussion

In this study, ePROs aim to collect information on patients’ self-reported health status, symptoms, and quality of life through digital device platforms. Although the vast amount of data from ePROs can help medical teams intervene early and improve patients’ side effects, it increases the workload of the medical team [

19,

20]. ChatGPT-4 can assist in effectively processing and analyzing these large volumes of self-reported data, enabling medical professionals to better understand patients’ needs and responses in an empathetic and emotionally supportive manner [

29].

The results show that the assessment of ChatGPT-4’s analysis of ePRO data in Traditional Chinese for 30 consecutively collected cancer patients was overall positive. ChatGPT-4 scored higher in completeness and accuracy, demonstrating its capability in handling and analyzing cancer patient ePRO data. This highlights the potential of AI in enhancing clinical decision-making and patient care, especially in integrating and evaluating extensive patient-reported outcomes.

The harm to patients was minimal, likely because we limited the scope of ChatGPT-4’s evaluation data exclusively to ePRO content [

30]. This suggests that we must still exercise caution when using AI technology to ensure it does not adversely affect patients. The medium scores for empathy and emotional support underscore the limitations of AI in addressing patients’ emotional needs and providing humanized care. This indicates that in practical applications, AI support should be combined with interpersonal interactions from healthcare professionals to meet patients’ comprehensive needs [

29].

Furthermore, this study may first demonstrate the potential of AI in assisting medical teams to use ePRO for patient care, improving communication efficiency with patients, reducing the stress of medical care, and increasing health literacy. Our results support the need for further research to explore and integrate ChatGPT-4 and other AI technologies into clinical ePRO cancer care, to promote patient-centered care and improve treatment outcomes.

Notably, the recommendations provided by ChatGPT-4 in the role of a dietitian received higher evaluations, which may reflect the importance of nutritional support in improving patient quality of life as recognized by doctors, dietitians, and nurses within the cancer care team. This could also indicate specific advantages of ChatGPT-4 in offering nutritional advice or highlight the unique importance of the dietitian’s role in patient care [

28].

However, ChatGPT-4.0, being a large language model, was not specifically designed to comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) [

2]. It may also present potential risks related to different races, ages, and genders. As for recommendations on cancer treatment, it has not achieved sufficient accuracy and lacks reference sources [

13,

14]. This study also found that when there is an excessive amount of ePRO side effect data, there is a risk of analysis errors by ChatGPT-4. Occasionally, it provided dietary advice for diarrhea that dietitians deemed inappropriate. In practical application, issues of data privacy, model bias, and decision interpretability must be considered. Future developments need to find a balance between technological innovation and legal, medical ethics to ensure that artificial intelligence not only enhances the efficiency of medical care but also protects the interests and rights of patients [

10].

Overall, the results of this study provide preliminary insights into the integration of AI tools like ChatGPT-4 in ePRO cancer care and highlight directions for future research and application. These include enhancing AI’s ability in emotional support and empathy, improving communication between physicians and patients, increasing patient health literacy, reducing the workload of healthcare providers, minimizing potential errors in AI-driven clinical processes, and further exploring the optimal use of AI across different medical professional roles. With technological advancements and more empirical research, AI has the potential to play a more significant role in ePRO cancer care and in the shared decision-making process between doctors and patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

For research articles with five authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions were provided. Conceptualization, Chih Ying Liao and Ti Hao Wang; methodology, Chih Ying Liao; software, Chih Ying Liao; validation, Chin Nan Chu, Ming Yu Lien and Yao Chung Wu; formal analysis, Chih Ying Liao; investigation, Chih Ying Liao; resources, Ti Hao Wang; data curation, Ti Hao Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Chih Ying Liao; writing—review and editing, Chih Ying Liao; visualization, Chih Ying Liao; supervision, Ti Hao Wang; project administration, Chih Ying Liao; funding acquisition, Ti Hao Wang. Chin Nan Chu, Ming Yu Lien and Yao Chung Wu, the three authors contributed equally to this work and share second authorship. Corresponding Author: Ti Hao Wang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is partially supported by China Medical University Hospital (CMUH)Grant DMR-111-076.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the institutional review board of China Medical University & Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan(No.:ePRO_HN_001/CMUH112-REC2-128(AR-1)).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The study detail data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This brief text acknowledges the contributions of the Radiation Oncology department at China Medical University Hospital, Cancell Tech Co. Ltd., and OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4 for their respective roles in this research and for assistance in polishing the English translation.

Conflicts of Interest

The first author, Chih Ying Liao, is a consulting scholar for the ePRO platform of Cancell Tech Co. Ltd.(

https://cancell.tw) for this study.The other four authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Figure A1.

The workflow of this study.

Figure A1.

The workflow of this study.

Table A1.

Example of GPT-4 evaluation of ePRO data in nasopharyngeal cancer patients.

Table A1.

Example of GPT-4 evaluation of ePRO data in nasopharyngeal cancer patients.

| Cancer type |

Quality of life |

Pain score |

Distress |

Body Weight(Kg) |

Temperature (°C) |

Appetite |

Epigastric discomfort |

Diarrhea |

Constipation |

Nausea/Vomiting |

Cough |

Dyspnea |

Fatigue |

Depression |

Insomnia |

Dermatitis |

| NPC |

3 |

3 |

3 |

90 |

36.9 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

| NPC |

3 |

2 |

3 |

90 |

36.9 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

| NPC |

2 |

3 |

2 |

90 |

36.9 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

| NPC |

3 |

2 |

4 |

89 |

36.7 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| NPC |

3 |

2 |

3 |

88 |

36.8 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| NPC |

2 |

2 |

2 |

88 |

36.8 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| NPC |

3 |

2 |

3 |

87 |

36.7 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| NPC |

2 |

2 |

2 |

87 |

36.8 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| NPC |

3 |

2 |

3 |

86 |

36.9 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

Table A2.

Patients’characteristics.

Table A2.

Patients’characteristics.

| Characteristics |

Numbers |

| Breast cancer |

8 |

| Head Neck cancer |

7 |

| Lung cancer |

3 |

| Prostate cancer |

2 |

| Pancreas cancer |

2 |

| Lymphoma |

2 |

| Renal cell carcinoma |

2 |

| Uterine sarcoma |

2 |

| Endometrial cancer |

2 |

| Stage |

|

| I |

5 |

| II |

7 |

| III |

8 |

| IV |

10 |

| Treatment modality |

|

| Chemotherapy |

12 |

| Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy |

8 |

| Radiotherapy |

5 |

| Target therapy |

5 |

Table A3.

The scores of GPT-4 acting as an oncologist evaluating ePRO data.

Table A3.

The scores of GPT-4 acting as an oncologist evaluating ePRO data.

| Completeness |

8.1 (7-10) |

| Accuracy |

8.2 (7-9) |

| Potential harm to the patient |

1.2 (0-3) |

| Empathetic response |

7.9 (6-10) |

| Emotional support |

7.6 (6-9) |

Improvement in patient

communication efficiency |

8 (7-9) |

| Reduction in medical care stress |

7.9 (6-10) |

| Increase in health literacy |

8.1 (7-10) |

Table A4.

The scores of GPT-4 acting as an oncology dietitian evaluating ePRO data.

Table A4.

The scores of GPT-4 acting as an oncology dietitian evaluating ePRO data.

| Completeness |

8.4(6-9) |

| Accuracy |

8.1(5-9) |

| Potential harm to the patient |

1.1(1-3) |

| Empathetic response |

7.6(6-9) |

| Emotional support |

7.5(6-9) |

Improvement in patient

communication efficiency |

8.4(5-9) |

| Reduction in medical care stress |

8.2(5-9) |

| Increase in health literacy |

8.3 (6-10) |

Table A5.

The scores of GPT-4.0 acting as an oncology nurse evaluating ePRO data.

Table A5.

The scores of GPT-4.0 acting as an oncology nurse evaluating ePRO data.

| Completeness |

8 (6-9) |

| Accuracy |

8.2 (7-9) |

| Potential harm to the patient |

0.9 (0-2) |

| Empathetic response |

7.7 (5-9) |

| Emotional support |

7.5 (7-8) |

Improvement in patient

communication efficiency |

8.3 (7-9) |

| Reduction in medical care stress |

8.1(6-9) |

| Increase in health literacy |

8.2 (5-9) |

References

- Open AI. ChatGPT: optimizing language models for dialogue. Available at: https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/ (accessed February 15, 2023). https://openai.com/about (accessed 2024-02-29).

- Uprety, D.; Zhu, D.; West, H. (Jack). ChatGPT—A Promising Generative AI Tool and Its Implications for Cancer Care. Cancer 2023, 129 (15), 2284–2289. [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J. W.; Poliak, A.; Dredze, M.; Leas, E. C.; Zhu, Z.; Kelley, J. B.; Faix, D. J.; Goodman, A. M.; Longhurst, C. A.; Hogarth, M.; Smith, D. M. Comparing Physician and Artificial Intelligence Chatbot Responses to Patient Questions Posted to a Public Social Media Forum. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023, 183 (6), 589. [CrossRef]

- Waisberg, E.; Ong, J.; Masalkhi, M.; Kamran, S. A.; Zaman, N.; Sarker, P.; Lee, A. G.; Tavakkoli, A. GPT-4: A New Era of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 1971 - 2023, 192 (6), 3197–3200. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A. M.; Logan, J. M.; Kichenadasse, G.; Sorich, M. J. Artificial Intelligence Chatbots Will Revolutionize How Cancer Patients Access Information: ChatGPT Represents a Paradigm-Shift. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2023, 7 (2), pkad010. [CrossRef]

- Browsing Is Rolling Back out to Plus Users (September 27, 2023).

- Kung, T. H.; Cheatham, M.; Medenilla, A.; Sillos, C.; De Leon, L.; Elepaño, C.; Madriaga, M.; Aggabao, R.; Diaz-Candido, G.; Maningo, J.; Tseng, V. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-Assisted Medical Education Using Large Language Models. PLOS Digit. Health 2023, 2 (2), e0000198. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tan, M. The Role of ChatGPT in Scientific Communication: Writing Better Scientific Review Articles. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2023, 13 (4), 1148.—.

- Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, S. Utility of ChatGPT in Clinical Practice. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e48568. [CrossRef]

- Dave, T.; Athaluri, S. A.; Singh, S. ChatGPT in Medicine: An Overview of Its Applications, Advantages, Limitations, Future Prospects, and Ethical Considerations. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1169595. [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Y. H.; Samaan, J. S.; Ng, W. H.; Ting, P.-S.; Trivedi, H.; Vipani, A.; Ayoub, W.; Yang, J. D.; Liran, O.; Spiegel, B.; Kuo, A. Assessing the Performance of ChatGPT in Answering Questions Regarding Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29 (3), 721–732. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S. B.; King, A. J.; Warner, E. L.; Aneja, S.; Kann, B. H.; Bylund, C. L. Using ChatGPT to Evaluate Cancer Myths and Misconceptions: Artificial Intelligence and Cancer Information. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2023, 7 (2), pkad015. [CrossRef]

- Dennstädt, F.; Hastings, J.; Putora, P. M.; Vu, E.; Fischer, G. F.; Süveg, K.; Glatzer, M.; Riggenbach, E.; Hà, H.-L.; Cihoric, N. Exploring Capabilities of Large Language Models Such as ChatGPT in Radiation Oncology. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2024, 9 (3), 101400. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Kann, B. H.; Foote, M. B.; Aerts, H. J. W. L.; Savova, G. K.; Mak, R. H.; Bitterman, D. S. Use of Artificial Intelligence Chatbots for Cancer Treatment Information. JAMA Oncol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Frailley, S. A.; Blakely, L. J.; Owens, L.; Roush, A.; Perry, T. S.; Hellen, V.; Dickson, N. R. Electronic Patient-Reported Outcomes (ePRO) Platform Engagement in Cancer Patients during COVID-19. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38 (29_suppl), 172–172. [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Deal, A. M.; Dueck, A. C.; Scher, H. I.; Kris, M. G.; Hudis, C.; Schrag, D. Overall Survival Results of a Trial Assessing Patient-Reported Outcomes for Symptom Monitoring During Routine Cancer Treatment. JAMA 2017, 318 (2), 197. [CrossRef]

- Meirte, J.; Hellemans, N.; Anthonissen, M.; Denteneer, L.; Maertens, K.; Moortgat, P.; Van Daele, U. Benefits and Disadvantages of Electronic Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Systematic Review. JMIR Perioper. Med. 2020, 3 (1), e15588. [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Barbera, L.; Kerrigan, C. L.; Velikova, G. Implementation of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Routine Medical Care. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2018, No. 38, 122–134. [CrossRef]

- Daly, B.; Nicholas, K.; Flynn, J.; Silva, N.; Panageas, K.; Mao, J. J.; Gazit, L.; Gorenshteyn, D.; Sokolowski, S.; Newman, T.; Perry, C.; Wagner, I.; Zervoudakis, A.; Salvaggio, R.; Holland, J.; Chiu, Y. O.; Kuperman, G. J.; Simon, B. A.; Reidy-Lagunes, D. L.; Perchick, W. Analysis of a Remote Monitoring Program for Symptoms Among Adults With Cancer Receiving Antineoplastic Therapy. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5 (3), e221078. [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Stover, A. M.; Schrag, D.; Chung, A.; Jansen, J.; Henson, S.; Carr, P.; Ginos, B.; Deal, A.; Spears, P. A.; Jonsson, M.; Bennett, A. V.; Mody, G.; Thanarajasingam, G.; Rogak, L. J.; Reeve, B. B.; Snyder, C.; Kottschade, L. A.; Charlot, M.; Weiss, A.; Bruner, D.; Dueck, A. C. Clinical Utility and User Perceptions of a Digital System for Electronic Patient-Reported Symptom Monitoring During Routine Cancer Care: Findings From the PRO-TECT Trial. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2020, No. 4, 947–957. [CrossRef]

- Rocque, G. B. Learning From Real-World Implementation of Daily Home-Based Symptom Monitoring in Patients With Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5 (3), e221090. [CrossRef]

- Denis, F.; Basch, E.; Septans, A.-L.; Bennouna, J.; Urban, T.; Dueck, A. C.; Letellier, C. Two-Year Survival Comparing Web-Based Symptom Monitoring vs Routine Surveillance Following Treatment for Lung Cancer. JAMA 2019, 321 (3), 306. [CrossRef]

- Lizée, T.; Basch, E.; Trémolières, P.; Voog, E.; Domont, J.; Peyraga, G.; Urban, T.; Bennouna, J.; Septans, A.-L.; Balavoine, M.; Detournay, B.; Denis, F. Cost-Effectiveness of Web-Based Patient-Reported Outcome Surveillance in Patients With Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14 (6), 1012–1020. [CrossRef]

- Schwartzberg, L. Electronic Patient-Reported Outcomes: The Time Is Ripe for Integration Into Patient Care and Clinical Research. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2016, No. 36, e89–e96. [CrossRef]

- Lokmic-Tomkins, Z.; Davies, S.; Block, L. J.; Cochrane, L.; Dorin, A.; Von Gerich, H.; Lozada-Perezmitre, E.; Reid, L.; Peltonen, L.-M. Assessing the Carbon Footprint of Digital Health Interventions: A Scoping Review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2022, 29 (12), 2128–2139. [CrossRef]

- Gesner, E.; Dykes, P. C.; Zhang, L.; Gazarian, P. Documentation Burden in Nursing and Its Role in Clinician Burnout Syndrome. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2022, 13 (05), 983–990. [CrossRef]

- Guveli, H.; Anuk, D.; Oflaz, S.; Guveli, M. E.; Yildirim, N. K.; Ozkan, M.; Ozkan, S. Oncology Staff: Burnout, Job Satisfaction and Coping with Stress. Psychooncology. 2015, 24 (8), 926–931. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M. B. ChatGPT as a Virtual Dietitian: Exploring Its Potential as a Tool for Improving Nutrition Knowledge. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2023, 6 (5), 96. [CrossRef]

- Sorin, V.; Brin, D.; Barash, Y.; Konen, E.; Charney, A.; Nadkarni, G.; Klang, E. Large Language Models (LLMs) and Empathy—A Systematic Review. August 7, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Athaluri, S. A.; Manthena, S. V.; Kesapragada, V. S. R. K. M.; Yarlagadda, V.; Dave, T.; Duddumpudi, R. T. S. Exploring the Boundaries of Reality: Investigating the Phenomenon of Artificial Intelligence Hallucination in Scientific Writing Through ChatGPT References. Cureus 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).