1. Introduction

A bunch of documents suggested the imbalance between the physical and psychological development of adolescents [

1,

2]. Specifically, adolescents’ emotional reactivity is increasingly developing, but the development of their cognitive control ability is not following [

3,

4,

5]. Grant et al. [

6] indicated that adolescents face many complex stressors and need to cope with various challenges [

7,

8]. These sources of challenges might stem from transitional periods from primary school to junior high school, coping with greater academic and exam pressure, experiencing more social interaction, dealing with conflicts with parents, and coping with public health emergencies (such as the COVID-19 pandemic) [

9]. Therefore, it’s obvious that adolescence is a period when mental health problems frequently happen, which leads to a greater disease burden and might influence lifelong health [

10,

11]. Previous research found that 10% -20% of adolescents worldwide were affected by mental health problems [

12,

13]. From the early 1990s to the mid-2000s, researchers found that different birth cohorts of Chinese adolescents’ mental health conditions have deteriorated, the scores for negative mental health indicators (i.e., anxiety and depression) increased, while the scores for positive indicators (i.e., self-esteem) were decreased [

14]. Another national investigation showed that with the rapid economic and social development in China, the prevalence of mental health problems among adolescents has increased [

15]. Therefore, adolescent mental health problems have become a major global public health problem. Studies on adolescent mental health and its promotion mechanism have significant contributions to theoretical development as well as real-world practices. However, previous research on adolescents’ mental health mainly focused on the perspective of psychopathology and used negative indicators (such as some indexes measured by SCL-90) to measure psychological diseases. In recent years, more and more researchers have pointed out that the research on mental health needs to be changed from the perspective of psychopathology to the perspective of positive psychology [

16,

17], which means that researchers should not only find ways to reduce mental illness but also promote mental health. Consequently, the current study conducted two studies and aimed to examine positive variables (i.e., emotional resilience and positive emotion), and to explore the possible mediated mechanisms for promoting adolescent mental health.

1.1. Emotional Resilience and Mental Health

Emotional resilience comes from psychological resilience. It refers to the individual's ability to generate positive emotions and recover quickly from negative emotional experiences under stress and adversity [

18]. Given the definition of emotion resilience, it’s obvious that emotion resilience is associated with positive or negative outcomes, mental health as a vital theme has received the most attention in current research.

According to the theory of Complete Mental Health, proposed by Keyes [

19] and suggested that people with complete mental health not only the absence of disease but also exhibit a positive and flourishing mental state, which could generate a high level of emotional and social adjustment [

20,

21]. Thus, mental health contains emotional and social aspects in the domain of positive psychology [

16]. Furthermore, the current study focused on emotional aspects, which contain positive and negative indicators [

22]. Draper et al. [

23] identified depression, anxiety, and emotional health as indicators of mental health, whereas, life satisfaction and self-esteem were also included in positive indicators of mental health in previous studies [

24,

25]. Consequently, we chose positive mental health indicators (i.e., life satisfaction, self-esteem) and negative mental health indicators (i.e., depression, anxiety).

Previous research showed that there was a close and significant relationship between emotional resilience and negative mental health indicators such as depression and anxiety among adolescents [

26,

27]. For example, Chung et al. [

26] found that adolescents who lived with single parents showed lower emotional resilience, which in turn was related to high levels of depression. Also, the results of a study conducted by Ramos-Díaz and his colleagues [

27] highlighted that the importance of developing resilience improves adolescent life satisfaction among adolescents. High levels of emotional resilience trigger adolescents multiple and flexible coping strategies among adolescents, as a result, which could generate high levels of self-esteem by solving problems easily [

26]. Even though, the possible mediated variable is not examined. From the perspective of positive psychology, positive emotion is a vital variable that has gotten more attention in recent years.

1.2. Emotional Resilience and Positive Emotions

Positive emotions are the pleasure feelings that are generated when individuals' physical and mental needs are satisfied [

28]. The Broaden-and-Build Theory (BBT) of positive emotions has important implications and enlightenment for exploring the relationship between emotional resilience and positive emotions in adolescents [

29]. According to the BBT, the relationship between emotional resilience and positive emotion was reciprocal, positive emotion could build emotional resilience, and the build of emotional resilience could generate more positive emotion. There was a mutual build and spiral process between the two [

30]. Regarding BBT, previous studies have paid more attention to the influence of positive emotion on emotional resilience. However, more and more evidence paid attention to emotion resilience has strong associations with positive emotions. The extent of experiencing positive emotion has improved the positive state, which is associated with positive mental health. Therefore, it’s essential to examine how positive emotions work for relations between emotional resilience and positive mental health. One study of adolescents showed that adolescents with low emotional resilience had lower levels of emotional pleasure than those with high emotional resilience [

31]. Another research on college students showed that one dimension of emotional resilience (the ability to generate positive emotions) could promote the generation of positive emotions and contribute to the reduction of negative emotions; meanwhile, another dimension of emotional resilience (the ability to recover from negative emotions) also directly reduced negative emotions [

32]. Researchers also found that adults could improve their mood through emotional resilience [

33]. Similarly, another experimental study indicated that adults with high emotional resilience presented bias towards positive emotions when faced with uncertain emotional expressions [

34].

1.3. Positive Emotion and Mental Health

Researchers argued that positive emotions are part of overall mental health, and should consider positive emotions an important factor of mental health [

19]. However, more and more researchers differentiated positive emotion and mental health as two different constructs through different operational definitions, and different measurements [

35,

36]. Positive emotions are emotional states that are related to the satisfaction of personal needs and are usually accompanied by the subjective experience of pleasure, including both transient emotions (i.e., pleasure) and diffuse and persistent positive emotions [

36]. Mental health is a functional component of an individual's overall psychological quality [

37]. Therefore, the scope of mental health is larger and relatively stable than positive emotions and is generally used as an outcome variable in studies. In the current study, positive emotion and mental health were treated as two different constructs, and mental health was the dependent variable.

The conclusion on the relationship between positive emotions and mental health was fairly consistent that positive emotions could promote mental health [

35,

38]. Positive emotions could help individuals to relieve depression, fear, and anxiety [

39]. Cultivating positive emotions was an effective way to eliminate individual psychological barriers and promote healthy mental status [

40]. However, there were few studies focused on positive emotions and mental health in the adolescent population.

1.4. The Present Study

To sum up, it was plausible that positive emotions mediate the relationship between emotional resilience and mental health. However, to date, these associations have not been specifically examined in adolescents. Moreover, there were some common biases in the theoretical framework and the operational definition of mental health in previous research which focused on the negative dimensions. Therefore, there was still great value in exploring the mechanism between emotional resilience and mental health in adolescents, and it was necessary to design more comprehensive indicators for mental health.

2. Study 1

2.1. Aims

The current study investigated the influence of adolescent emotional resilience on mental health and the mediating role of positive emotion. By using the complete mental health theory, the current study considered both positive (i.e., life satisfaction and self-esteem) and negative mental health indicators (i.e., depression and anxiety). We hypothesized that emotional resilience affected mental health through positive emotions, and positive emotions mediated the relationship between emotional resilience and mental health.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Participants

Totally 8 schools (3 high schools and 5 middle schools) in Shanghai, People’s Republic of China, were chosen to be involved in the current study. 3 classes were randomly selected from each grade level in every school. Totally 3,480 questionnaires were sent out and 3,086 valid student questionnaires were finally collected. The return recovery rate of the questionnaire was 88.7%. Participants were 3086 sixth- to twelfth-grade students with ages ranging from 12 to 19 years (Mage = 14.78 years, SD = 2.08 years; 49.84% boys, 50.16 % girls; 24.50% 6th grade, 16.95% 7th grade, 16.14% 8th grade, 10.56% 9th grade,11.44 % 10th grade, 11.50% 11th grade, 8.91% 12th grade).

2.2.2. Measures

Emotional Resilience was measured using The Adolescents' Emotional Resilience Questionnaire (AERQ), which was developed by Zhang and Lu [

41]. AERQ contains 11 items and generates two dimensions: the ability to generate positive emotions (GPE) (e.g., “When I’m in a bad mood, I can think of happy things”) and the ability to recover from negative emotions (RNE) (e.g., “I can adjust my negative emotions in a short time”). Each item was rated on a 6-point scale (from 1 = complete non-conformity to 6 = complete conformity). A higher test score indicates a high level of emotional resilience. The whole scale showed good reliability (Cronbach's

α = 0.83). Meanwhile, the reliability for GPE and RNE dimensions were very good, which was 0.84 and 0.76 respectively.

Positive emotion was measured by positive affect items in the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale for Children (PANAS-C) [

42], originally developed by Laurent et al. [

43]. This measure included 15 items (Cronbach's α = 0.92). Each item was a word that described positive emotion, such as "happy," et al. Using a 5-point rating, participants rated the extent of their own emotions (e.g., “How strongly do you feel happy in the past few weeks?”), ranging from 1 (none) to 5 (very strong). The higher the total score, the higher the level of positive emotion. In the current study, Cronbach's α of the Positive Emotion Questionnaire was 0.92.

Life satisfaction was measured by the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) with 5 items. This scale was developed by Diener et al. [

44], the scale was widely used in China with good reliability and validity [

45]. Using 7 points, from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). participants were asked to make subjective evaluations of their perceptions and experiences of life quality (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”). The higher the total score, the higher the level of life satisfaction. Cronbach's α in this study was 0.85.

Self-esteem was measured by the Self-Esteem Scale with 10 items and used in previous studies [

46,

47], which used 5 rating points, ranging from 1 (complete non-conformity) to 5 (complete conformity). A higher total score indicated a higher level of self-esteem (e.g., “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”). Previous studies have shown that the scale had good reliability and validity [

46,

47]. Cronbach's α in this study was 0.83.

Depression was measured by the Center for Epidemic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) with 20 items. The scale was developed by [

48]. The scale required participants to make a subjective assessment of the frequency of depressive symptoms in the last week (e.g., “It's hard for me to concentrate”), which showed good reliability and validity when used in middle school students and was suitable for Chinese adolescents [

49]. The questionnaire adopted a 4-point scale of 0-3, with 0, 1, 2, and 3 respectively representing: Occasional or no (less than one day in a week), sometimes (1-2 days in a week), frequent or half of the time (3-4 days in a week), most of the time or duration (5-7 days in a week). The higher the total score, the levels of depressive symptoms higher. Cronbach's α in this study was 0.91.

Anxiety was measured by the "Trait Anxiety Questionnaire" with 20 items adopted from previous studies [

50,

51]. Taking the emotion experienced by themselves as a reference, the subjects made four comments on the conditions described in the scale (e.g., “I worry too much about things that don't really matter”), 1 for almost none, 2 for some, 3 for frequent, and 4 for almost always. A higher total score indicated a higher level of anxiety. Previous studies have shown that the reliability and validity of the questionnaire meet the requirements of psychometrics [

50,

51]. Cronbach's α in this study was 0.87.

2.2.3. Procedures

Data were collected in April and May in 2021. The current study was recognized and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of BLINDED University before collecting the data. All aged from 12 to 18 students and their parents are informed to sign themselves on informed consent willingly. Students were allowed to leave the research whenever they wanted even if they signed themselves on informed consent before.

All data used in the current study were collected from students and through a paper-based questionnaire. All questionnaires were collected by trained investigators, who went to the class and provided face-to-face instructions to all students. Then the investigators collected the questionnaires carried the data back and properly stored it in the laboratory.

2.2.4. Data analysis

SPSS 22.0 and the SPSS Process Macro were used for all analyses involved in the current study.

2.3. Results

2.3.1. The Control and Verification of the Common Method Variance

Since all variables used in the current study were measured by students' self-report, there might be a common method variance (CMV) effect. Moreover, the Harman single-factor test was used to test the CMV [

52]. Exploratory factor analysis without rotation was carried out on all variables, and the results showed that there were 13 factors with characteristic roots greater than 1, and the variation explained by the first factor was 25.42%, far less than the critical value of 40%. Therefore, there is no obvious CMV effect in this study.

2.3.2. Descriptive Statistics

The results in

Table 1 indicate a strong positive correlation between emotional resilience, positive emotions, and positive indicators of mental health such as life satisfaction and self-esteem. Conversely, there is a significant negative correlation between emotional resilience, positive emotions, and negative indicators of mental health such as depression and anxiety.

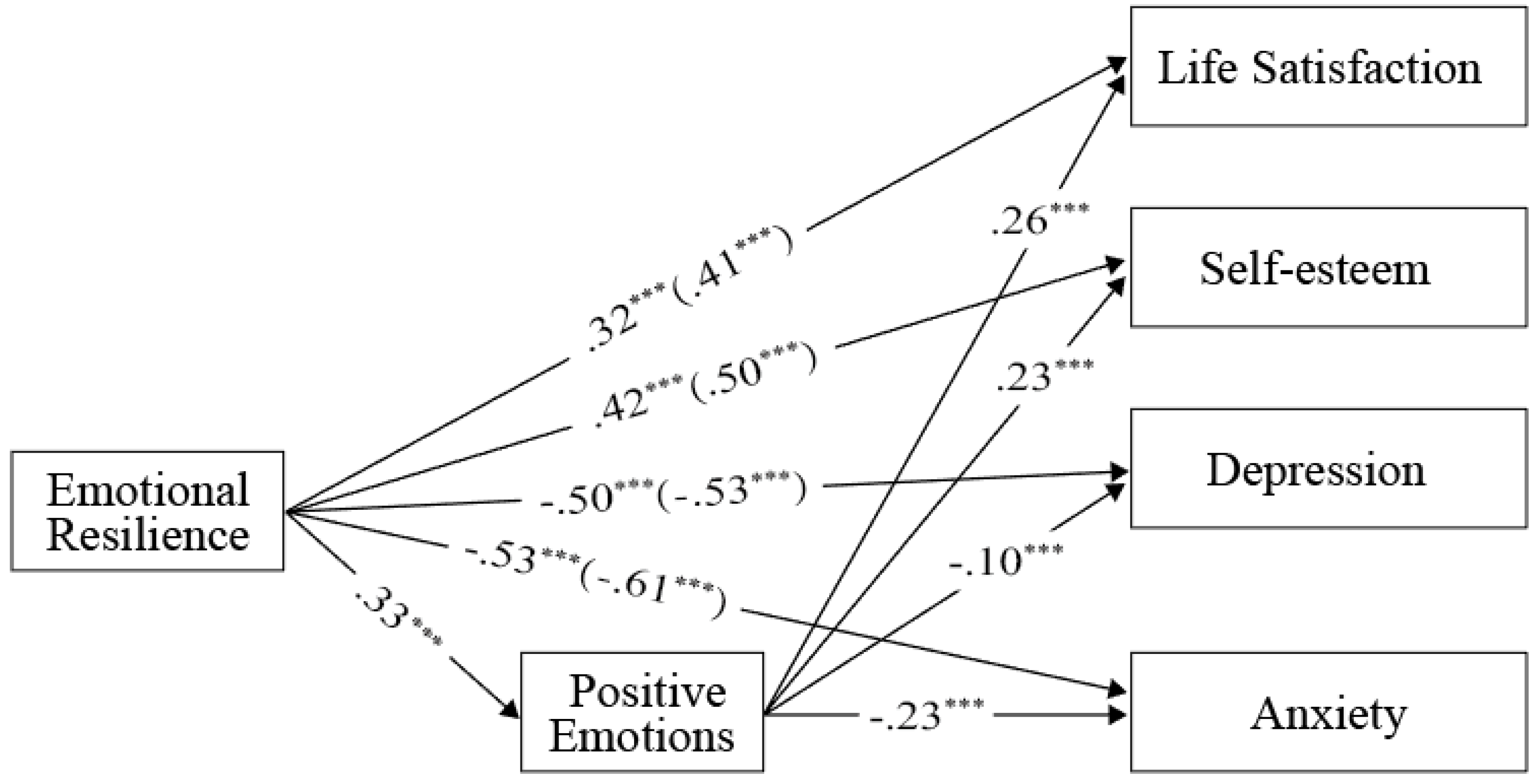

2.3.3. The Mediating Effect of Positive Emotion on the Relationship between Emotional Resilience and Mental Health (model 1)

The current study used the SPSS Process Macro [

53] to test model 1. As shown in

Table 2, after controlling for demographic variables such as gender and age, the results indicated that positive emotions partially mediated the relationship between emotional resilience and mental health. The results of the Bootstrap test showed that the 95% confidence interval did not include the number 0, and the mediating effect was significant. As seen in

Figure 1, the total (expressed as regression coefficients in parentheses) and direct effects of emotional resilience were also significant.

2.4. Discussion

Overall, the hypothesis of Study 1 was supported by the results. More specifically, the current study found that there was a significant relationship between emotional resilience and mental health. Meanwhile, positive emotions significantly mediated the relationship between emotional resilience and mental health. This study explored the important influence of emotional resilience on mental health through positive emotion, which provided empirical evidence and enrichment of the BBT of positive emotion.

Giving those results, which is consistent with previous studies. Emotional resilience is predicated on negative mental health indicators negatively [

39] and is mediated by positive emotions. One possible explanation for such a finding could be attributed to the building effect of positive emotions. Cohen et al. [

30] proposed that positive emotions can build psychological resources (i.e., cognitive ability), social resources (i.e., interpersonal relationships), and physical resources (i.e., sleep time). According to this characteristic of positive emotions, individuals with high emotional resilience adopt positive coping strategies when facing stress [

54]. Thus, promoting the generation and maintenance of positive emotions, using positive emotions to one’s advantage, and flexibly using them can ultimately lead to good mental health outcomes. Researchers further pointed out that, in stressful situations, positive emotions are valuable tools that could help individuals achieve beneficial outcomes [

55].

In conclusion, the results of this study indicated that emotional resilience had a significant positive predictive effect on positive emotions and mental health and that positive emotions had a significant mediating effect in the relation between emotional resilience and mental health (life satisfaction, self-esteem, anxiety, depression).

3. Study 2

3.1. Aims

To further investigate the relationship between emotional resilience and mental health, study 2 used the data from a longitudinal study to explore the impact of adolescent emotional resilience on mental health and the mediating effect of positive emotions on the relationship between emotional resilience and mental health.

The results of regression analysis in study 1 indicated that emotional resilience not only positively affects positive mental health indicators (i.e., life satisfaction, self-esteem) but also negatively influences negative mental health indicators (i.e., depression, anxiety). However, in study 1, four indicators of mental health were used for analysis independently rather than the overall mental health index. We could not simply add the positive and negative mental health scores and get a total mental health score because they used different scoring methods. To scientifically calculate the mental health index, the current study referred to how another study calculated the overall teacher-student relationship quality index [

56]. Similar to Coplan et al. [

56], the current study calculated the complete mental health index by subtracting the negative mental health score from the positive mental health score.

In summary, this study uses longitudinal data to examine the mechanism of emotional resilience on mental health, which includes two aims. The first aim was to investigate the mechanism of T1 emotional resilience on the four indicators of T2 mental health. The second aim was to form a complete mental health index and investigate the mechanism of T1 emotional resilience on T2 complete mental health.

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Participants

Totally 266 adolescents were recruited, which included 146 boys (54.9%) and 120 girls (45.1%). The participants’ ages ranged from 12 to 18 years old, which had an average age of 14.11 years old (SD = 1.77). The participants involved in the study 2 were randomly selected from the samples in study 1. More specifically one grade level was randomly selected in each three high schools involved in study 1, then one class was randomly selected in the selected grade level. Similarly, one grade level was randomly selected in each five middle schools involved in study 1, then one class was randomly selected in the selected grade level. Therefore, a total of three high school classes and five middle school classes were selected for the longitudinal study. 291 questionnaires were distributed and 266 valid student questionnaires were collected, the effective return rate of the questionnaires was 91.4%.

3.2.2. Measures

The tools used to measure emotional resilience, positive emotions, life satisfaction, self-esteem, depression, and anxiety were the same as in Study 1.

3.2.3. Procedures

Measurement of T1, as in Study 1.

Part of the data collected in Study 1 was used as T1 data. All T2 data were collected 6 months after study 1, which means T2 data were collected in May and June in 2021. After confirming the participants should be involved in the T2, informed consent was collected from students and their parents. The teachers of mental health education in each selected school helped to distribute the T2 questionnaires and collect the T2 data.

After the consent of the school, the students, and the parents of the students, the investigation at T2 time should be carried out by the teachers of mental health education. The 266 students who had participated in the T1 survey completed the questionnaire again 6 months later through the paper-and-pencil test, and the questionnaire was collected on the spot after the completion of the questionnaire.

3.2.4. Statistical Analysis

The same as in Study 1.

3.3. Results

3.3.1. The Control and Verification of Common Method Variance

There might be a CMV effect in the current study because all data used were self-reported. To effectively reduce such effect, the process control was first used, which was the same as it used in study 1. Then, the Harman single-factor test was used to test the CMV [

52], and all variables were analyzed by exploratory factor analysis without rotation. For the T1 test, the results showed that there were 13 factors with characteristic roots greater than 1, and the variation explained by the first factor was 31.88%, which was less than the critical value of 40%. For the T2 test, the results showed that there were 15 factors with characteristic roots greater than 1, and the variation explained by the first factor was 32.73%, which was less than the critical value of 40%. Therefore, there were no obvious CMV effects in this study.

3.3.2. The Mediating Effect of Positive Emotion on the Relationship between Emotional Resilience and Mental Health (model 2)

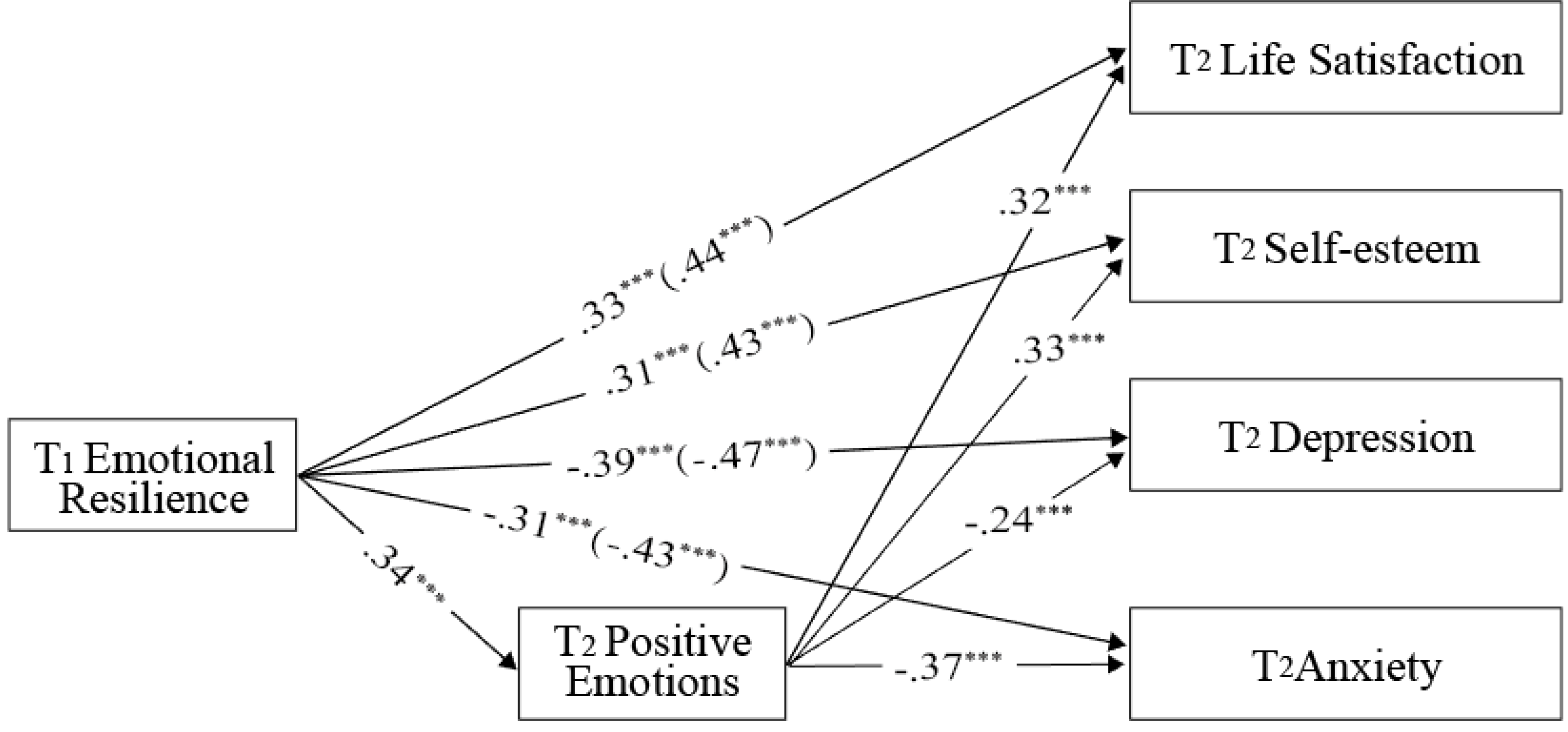

As shown in

Table 3, the descriptive statistics and the relationships among T1 emotional resilience, T2 positive emotion, and T2 mental health indicators were reported. Regarding the correlations among studied variables, T1 emotional resilience, T2 positive emotion, and T2 positive indicators of mental health (i.e., life satisfaction and self-esteem) were significantly and positively correlated. Moreover, there was a significant negative correlation among T1 emotional resilience, T2 positive emotion, and T2 negative mental health indicators (i.e., depression and anxiety). The correlational results from this longitudinal study were similar to the correlational results in study 1, which was a cross-sectional study.

By using the SPSS Process Macro, the mediating effects of T2 positive emotions on the relationship between T1 emotional resilience and four T2 mental health indicators were tested. As shown in

Table 4, after controlling for gender and age, the results suggested that T2 positive emotions partially mediated the relationship between T1 emotional resilience and T2 mental health. The Bootstrap test results showed that the 95% confidence interval did not include the number 0, and the mediating effect was significant. As can be seen from

Figure 2, the total and direct effects of emotional resilience were also significant.

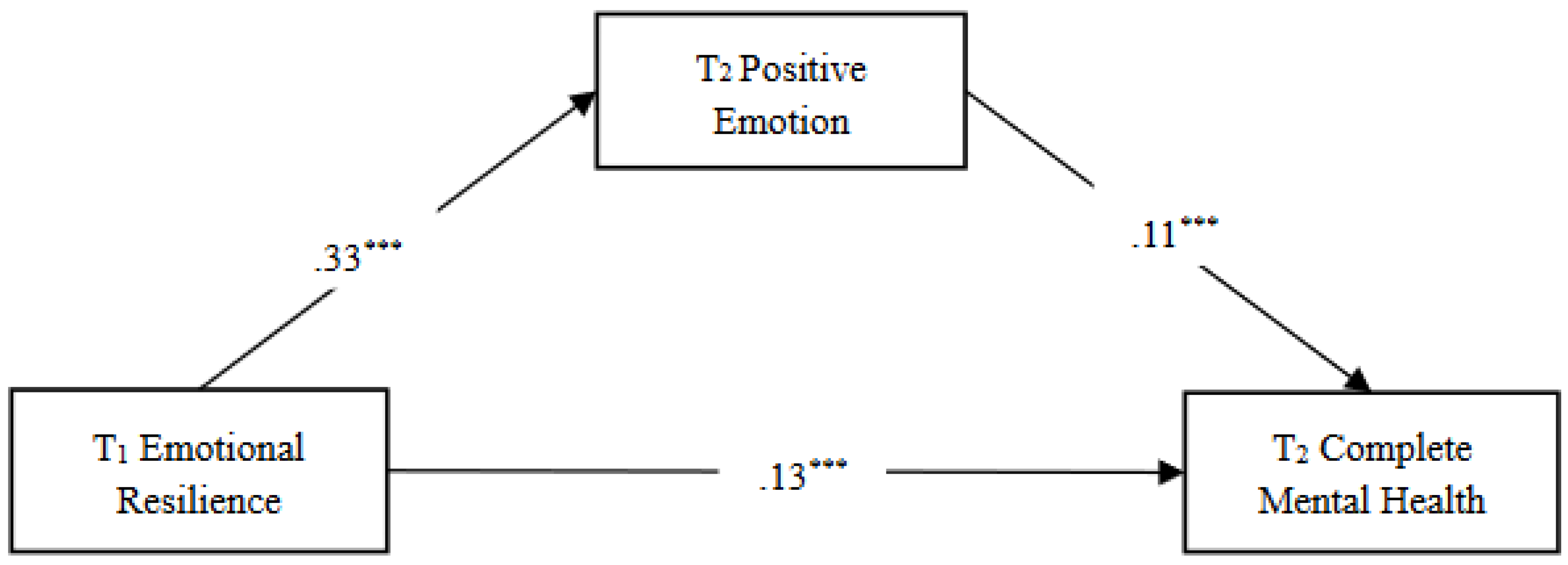

3.3.3. The Mediating Effect of Positive Emotions on the relationship between Emotional Resilience and Complete Mental Health (model 3)

After computing the standard scores (z score) for positive mental health, negative mental health, and complete mental health, the correlation coefficients were computed. As shown in

Table 5, the results indicated that both emotional resilience and positive emotions were positive and significantly related to positive and complete mental health, but negative and significantly related to negative mental health. Regarding participants' complete mental health level, it was found that 175 participants (65.8%) were at average or above average, and 91 participants (34.2%) were below average.

Note. The values of positive mental health, negative mental health, and complete mental health in this table were standardized scores.

Regarding the mediating effect of positive emotions on the relationship between emotional resilience and complete mental health, the results suggested that T2 positive emotions played a partial mediation role between T1 emotional resilience and T2 complete mental health. The Bootstrap test results showed that the 95% confidence interval did not include the number 0, the mediating effect was significant, and the proportion of the mediating effect was 23.54% (

Table 6) From Figure 4, it could be seen that the total effect of emotional resilience (expressed by the regression coefficient in brackets) and the direct effect were also significant.

3.4. Discussion

The current study answered the question regarding how adolescents’ emotional resilience and positive emotions affect their mental health over time. Overall, the hypothesis of this study was strongly supported by the data.

First of all, based on study 1, study 2 used longitudinal data to further support the positive influence of emotional resilience on mental health.

Secondly, the results of both model 2 and model 3 showed that positive emotions partially mediated the relationship between emotional resilience and mental health, which was also consistent with the results of study 1. The difference was that Study 2 used longitudinal data and introduced complete mental health indicators.

The research on mental health went through three main stages: the tendency for mental illness, the tendency for positive mental function, and the tendency for complete mental health [

57]. The maintenance of complete mental health required not only reducing mental illness but also promoting mental health [

19]. Previous studies have mainly focused on positive and negative mental health rather than measuring complete mental health as one construct [

16,

22]. Therefore, in the current study, the positive and negative mental health indicators were combined into one continuous variable to represent the complete mental health level. Moreover, the current research focused on the sample of adolescents rather than younger adults or seniors, which gave a more comprehensive picture of the relationship between emotional resilience, positive emotions, and complete mental health.

The theory and practice of complete mental health pointed out that mental health policy should not only seek effective ways to prevent and treat mental illness but also find effective interventions to help more people achieve complete mental health [

58]. The implementation of policies and practice of complete mental health needed the support of empirical evidence, especially the evidence on identifying the key factors to promote complete mental health. This study revealed the positive and predictive role of emotional resilience on complete mental health as well as the significant mediating role of positive emotions on the relationship between emotional resilience and complete mental health, which all had enlightenment to building interventions for adolescents’ complete mental health.

In study 2, emotional resilience showed a significant effect on positive mental health (i.e., life satisfaction and self-esteem), negative mental health (i.e., depression and anxiety), and complete mental health. More specifically, emotional resilience significantly and positively predicted life satisfaction, self-esteem, and, complete mental health, whereas it showed significant and negative effects on depression and anxiety. Moreover, positive emotions played a partial mediation role in the relationship between emotional resilience and mental health (i.e., positive mental health, negative mental health, and complete mental health). The current study focused on emotional resilience and positive emotions and provided some enlightenment on potential ways to improve adolescent’s complete mental health.

4. General Discussion

The current study proposed that adolescents’ emotional resilience might affect their positive emotions and mental health, and focused on the main assumption that emotional resilience could promote mental health through positive emotions. The current research used 2 studies to explore the assumption and the results found that adolescent emotional resilience played a role in their mental health in at least two possible ways.

On the one hand, emotional resilience has a direct impact on mental health. In the three models involved in Study 1 and Study 2, the results indicated that emotional resilience significantly affected mental health. More specifically, emotional resilience had a significant effect on positive mental health (i.e., life satisfaction and self-esteem), negative mental health (i.e., depression and anxiety), and complete mental health indicators. Among them, emotional resilience had a significant positive effect on life satisfaction, self-esteem, and complete mental health, whereas it had a significant negative effect on depression and anxiety.

Previous studies found that psychological resilience had a significant influence on mental health [

22,

26,

40] The current study focused on a specific type of psychological resilience, emotional resilience, and found that it also had a significant effect on mental health, which deepened the research on the relationship between psychological resilience and mental health. In addition, building on Keyes's [

19] theoretical framework of complete mental health, this research not only focused on the positive indicators of mental health (i.e., life satisfaction and self-esteem) but also the negative indicators of mental health (i.e., depression and anxiety). Emotional resilience showed a significant effect on all positive, negative, and complete mental health indexes.

On the other hand, emotional resilience influences mental health through positive emotions. In general, positive emotions had a significant mediating effect on the relationship between emotional resilience and life satisfaction, self-esteem, anxiety, and depression (models 1 and 2) as well as on the relationship between emotional resilience and complete mental health (model 3).

The significant mediating effect of positive emotions indicated that it played a significant role in promoting mental health, which also received much attention in the field of contemporary positive psychology. Seligman [

59] considered positive emotions as one of the three main concepts of positive psychology and built the PERMA model of positive psychology: P stood for positive emotions, E stood for engagement, R stood for relationship, M stood for meaning, and A stood for achievement. This model not only revealed the source of the positive mental state but also highlighted the role of positive emotions in the initiation and stimulation of a positive mental state. Happiness was easily forgotten, while sadness was easily remembered, and people usually paid more attention to negative emotions than to positive ones. Extensive research on positive emotions emerged during the beginning of the 20th century, more attention was given to the important role of positive emotions on mental health [

60,

61]. Negative emotions tend to be evasive and narrow down the outcome of behavior. Unlike the behavioral consequences of negative emotions, positive emotions have a common tendency, which lets individuals approach or continue to engage in activities that give them a positive experience. The initiation of dynamic processes and behaviors (i.e., exploration, learning, and building connections with others) relied on positive emotions. Positive emotions promote mental and physical health. People should cultivate positive emotions in their daily lives not only because they feel good in the moment, but also helped them to get better and leads them to prosperity, health, and longevity. The BBT of positive emotions emphasized that positive emotions were the core factors to help individuals reach their optimum functions and move forward to a more psychologically healthy status [

28,

35].

4.1. Educational Implications from the Current Investigation

Integrating the findings from previous research (focused on how positive emotions promoted emotional resilience) and the current study (focused on how emotional resilience promoted positive emotions), positive emotions could build a positive cycle between emotions and the construction of positive psychological resources (including emotional resilience), Moreover, positive emotions could be cultivated in daily life, which provided important implications for the practice of promoting mental health through positive emotions. Psychological resilience was often associated with positive emotions that were generated during difficult situations but not related to lower negative emotions arousal [

54]. It was not difficult to generate positive emotions. They could be generated in daily activities (i.e., interacting with others, helping others, playing, and learning). As such abundant endogenous resources, positive emotions were yet to be discovered, and people might use these endogenous resources to stimulate the process of spiral escalation (i.e., positive emotions helped people construct psychological resources, and then more psychological resources led to more positive emotions, thus creating a positive cycle), which could improve their health and well-being [

35]. Individuals could carve out their way to health and well-being if they can find ways to foster their positive emotions [

55].

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

Even though the current study provided much enlightenment for the research on emotional resilience, there were some limitations. First of all, the findings of the current study mainly relied on the data from questionnaires. Even though the current study used both cross-sectional and longitudinal data, future studies might consider other methods or mixed methods, such as questionnaires, behavioral experiments, and cognitive neuroscience methods. In that way, researchers might get more convergent conclusions about the influence of emotional resilience on mental health.

Secondly, more detailed and complex studies needed to be done to explore the influence of emotional resilience on positive emotions. Studies have shown that positive emotions could be further divided into two types, namely, high-approach positive emotions and low-approach positive emotions. High-approach positive emotions included enthusiasm, desire, excitement, etc, while low-approach positive emotions included fun, satisfaction, love, and gratitude. The former was the emotion that drove reward-seeking and motivated the impulse to action or approach in the future, and the latter was the feeling of savoring the present, which was generally no trigger for approaching behavior or related actions [

62]. Whether there were differences in the effects of emotional resilience on the two types of positive emotions, and whether there were differences in the effects of the two types of positive emotions on mental health, was worth further discussing.

Third, the impact of positive emotions on mental health needs to be further explored. For example, positive emotion disturbances might have negative effects on mental health. Studies have explored the relationship between positive emotions and mental disorders, showing that excessive positive emotions have a significant predictive effect on a range of clinical syndromes. These included: Illegal and problematic drug and alcohol use, risky sexual behavior, bulimia, gambling, high mortality, and more. In addition, individuals who failed to down-regulate too high a positive mood were predisposed to mania [

60].

5. Conclusions

Adolescents' emotional resilience had a significant predictive effect on mental health. Among them, emotional resilience had a positive predictive effect on life satisfaction, self-esteem, and complete mental health, and had a negative predictive effect on depression and anxiety. Emotional resilience plays an important role in both reducing mental problems and promoting mental health. Adolescents' emotional resilience could not only directly affect mental health, but also indirectly affect mental health through positive emotions.

References

- Keyes, K.M.; Platt, J.M. Annual Research Review: Sex, gender, and internalizing conditions among adolescents in the 21st century–trends, causes, consequences. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry 2024, 65, 384–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, A.S.; Watrous, J.N.H.; Hays-Grudo, J. Character strengths and resilience in adolescence: a developmental perspective. J. Posit. Psychol. 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Riser, D.; Deater-Deckard, K. Emotional Development. Encyclopedia of Adolescence 2011, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- du Pont, A. , Welker, K., Gilbert, K. E., & Gruber, J. The emerging field of positive emotion dysregulation. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory and applications, 2016, 364-379.

- Rónai, L.; Hann, F.; Kéri, S.; Ettinger, U.; Polner, B. Emotions under control? Better cognitive control is associated with reduced negative emotionality but increased negative emotional reactivity within individuals. Behav. Res. Ther. 2024, 173, 104462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, K.E.; Behling, S.; Gipson, P.Y.; Ford, R.E. Adolescent stress: The relationship between stress and mental health problems. Prevention Researcher 2005, 12, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Regueiro, F.; Núñez-Regueiro, S. Identifying Salient Stressors of Adolescence: A Systematic Review and Content Analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 2533–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisk, L.M.; Gee, D.G. Stress and adolescence: vulnerability and opportunity during a sensitive window of development. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 44, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simuforosa, M. Stress and adolescent development. Greener journal of educational research 2013, 3, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S.; Khan, M.N.; Mahmood, W.; Patel, V.; Bhutta, Z.A. Interventions for Adolescent Mental Health: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2016, 59, S49–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Flisher, A.J.; Hetrick, S.; McGorry, P. Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet 2007, 369, 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre Velasco A, Cruz I S S, Billings J, et al. What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviors for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 1–22.

- Ma, L.; Mazidi, M.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Kirwan, R.; Zhou, H.; Yan, N.; Rahman, A.; Wang, W.; et al. Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, Z.; Niu, J.; Chi, L. Birth cohort changes in Chinese adolescents’ mental health. Int. J. Psychol. 2011, 47, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health Commission. Healthy China Action Plan on Mental Health for Children and Adolescents (2019-2022) 2019, 2020-03-20 from http: //www.nhc.gov.cn.

- Arslan, G.; Yıldırım, M.; Zangeneh, M.; Ak, I. Benefits of Positive Psychology-Based Story Reading on Adolescent Mental Health and Well-Being. Child Indic. Res. 2022, 15, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zyl, L.E.; Gaffaney, J.; van der Vaart, L.; Dik, B.J.; I Donaldson, S. The critiques and criticisms of positive psychology: a systematic review. J. Posit. Psychol. 2023, 19, 206–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.J. Affective neuroscience and psychophysiology: Toward a synthesis. Psychophysiology 2003, 40, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am. Psychol. 2007, 62, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, G.; Allen, K.-A. Complete mental health in elementary school children: Understanding youth school functioning and adjustment. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 41, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G.; Renshaw, T.L. Student Subjective Wellbeing as a Predictor of Adolescent Problem Behaviors: a Comparison of First-Order and Second-Order Factor Effects. Child Indic. Res. 2017, 11, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yu, Z.; Lin, D. Meta-analysis of the relationship between psychological resilience and mental health in children and adolescents. Psychology and Behavior 2019, 17, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Draper, C.E.; Cook, C.J.; Redinger, S.; Rochat, T.; Prioreschi, A.; Rae, D.E.; Ware, L.J.; Lye, S.J.; Norris, S.A. Cross-sectional associations between mental health indicators and social vulnerability, with physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep in urban African young women. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moksnes, U.K.; Espnes, G.A. Self-esteem and life satisfaction in adolescents—gender and age as potential moderators. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 2921–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Cheng, Q. Relationship between online social support and adolescents’ mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Lam, K.; Ho, K.; Cheung, A.; Ho, L.; Gibson, F.; Li, W. Relationships among resilience, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents. J. Heal. Psychol. 2018, 25, 2396–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Díaz, E.; Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Axpe, I.; Ferrara, M. Perceived Emotional Intelligence and Life Satisfaction Among Adolescent Students: The Mediating Role of Resilience. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 20, 2489–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Positivity: Groundbreaking research reveals how to embrace the hidden strength of positive emotions, overcome negativity, and thrive. Crown Publishers, New York, United States, 2009.

- Fredrickson, B.L. What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology 1998, 2, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, M.A.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Brown, S.L.; Mikels, J.A.; Conway, A.M. Happiness unpacked: Positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion 2009, 9, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M. Adolescent Emotional Resilience and Its Effects on Cognition. Doctor’s Thesis, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2010.

- Wang, Y.; Xu, W.; Luo, F. Emotional Resilience Mediates the Relationship Between Mindfulness and Emotion. Psychol. Rep. 2016, 118, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang; Y; Qi, Z. ; Liu; X The role of emotional resilience in mindfulness training in improving mood state. Chinese Journal of Mental Health 2017, 31, 914–915.

- Arce, E.; Simmons, A.N.; Stein, M.B.; Winkielman, P.; Hitchcock, C.; Paulus, M.P. Association between individual differences in self-reported emotional resilience and the affective perception of neutral faces. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 114, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Joiner, T. Reflections on Positive Emotions and Upward Spirals. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, W. ; Du; J; &Wang, K. The relationship between positive emotion and mental health of college students: The mediating effect of personal resources. Chinese Journal of Mental Health 2011, 25, 521–527. [Google Scholar]

- Chen; L; &Zhang; D The progress and trend of adolescent mental health research in China in the past 20 years. Higher Education Research 2009, 30, 74–79.

- Dong, Y. ; Wang; Q; &Xing; C Progress in the study on the relationship between positive emotion and physical and mental health. Psychological Science 2012, 35, 487–493. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, V.; Paes, F.; Pereira, V.; Arias-Carrión, O.; Silva, A.C.; Carta, M.G.; Nardi, A.E.; Machado, S. The Role of Positive Emotion and Contributions of Positive Psychology in Depression Treatment: Systematic Review. Clin. Pr. Epidemiology Ment. Heal. 2013, 9, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gloria, C.T.; Steinhardt, M.A. Relationships Among Positive Emotions, Coping, Resilience and Mental Health. Stress Heal. 2014, 32, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; &Lu, J. ; &Lu, J. Research report on the emotional resilience questionnaire for adolescents. Psychological Science 2010, 33, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, T.; Ding, X.; Sang, B.; Liu, Y.; Xie S &Feng, X. ; Xie S &Feng, X. Reliability and validity of positive and negative affective scale for children (PANAS-C). Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology 2015, 23, 397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, J.; Catanzaro, S.J.; Joiner, T.E.; Rudolph, K.D.; Potter, K.I.; Lambert, S.; … Gathright, T. A measure of positive and negative affect for children: Scale development and preliminary validation. Psychological Assessment 1999, 11, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 1985, 49(1), 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Fang, L.; Stith, B.R.; Liu, R.-D.; Huebner, E.S. A Psychometric Evaluation of the Chinese Version of the Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2017, 13, 1081–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zuo, B.; Wen, F.; Yan, L. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Method Effects, Factorial Structure and Scale Invariance Across Migrant Child and Urban Child Populations in China. J. Pers. Assess. 2016, 99, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, F.; Xin, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L. Gender difference of Chinese high school students’ math anxiety: The effects of self-esteem, test anxiety and general anxiety. Sex Roles 2019, 81, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-depression scale for research in the general population. Journal of Applied Psychological Measurement 1977, 1, 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Tang, S.; Ren, Z.; Wong, D.F.K. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among adolescents in secondary school in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 245, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Genetic and environmental contributions to anxiety among Chinese children and adolescents – a multi-informant twin study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 56, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T. The Chinese version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: Its relationship to different measures of psychological well-being. Journal of Clinical Psychology 1993, 49, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford Press, New York, United States, 2013.

- Troy, A.S.; Mauss, I.B. Resilience in the face of stress: Emotion regulation as a protective factor. Resilience and mental health: Challenges across the lifespan 2011, 1, 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- LaBelle, B. Positive Outcomes of a Social-Emotional Learning Program to Promote Student Resiliency and Address Mental Health. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coplan, R.J.; Liu, J.; Cao, J.; Chen, X.; Li, D. Shyness and school adjustment in Chinese children: The roles of teachers and peers. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2017, 32, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y. Relationship between socioeconomic status and mental health among college students from the perspective of complete mental health. Journal of North Nationality University (Philosophy and Social Sciences) 2017, 5, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Fledderus, M.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; Smit, F.; Westerhof, G.J. Mental Health Promotion as a New Goal in Public Mental Health Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Intervention Enhancing Psychological Flexibility. Am. J. Public Heal. 2010, 100, 2372–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, M. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 13, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, J.; Purcell, J. Positive Emotion Disturbance. In Scott, R.A., Kosslyn, S.M. & Buchmann, M.C. Eds. Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource. John Wiley & Sons. (pp.1–12). New York, United States, 2015.

- Sang; B; Deng, X. ; &Luan; Z Which emotional regulatory strategy makes Chinese adolescents happier? a longitudinal study. International Journal of Psychology 2014, 49, 513–518.

- Gilbert, K.E. The neglected role of positive emotion in adolescent psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 32, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).