Submitted:

25 June 2024

Posted:

26 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS) and Bioinformatic Analysis

2.2. Genomic Analysis of New Viroid Species

2.3. Genomic Analysis of the Detected Viruses

2.4. Validation of the Detected Viruses and Viroids

2.5. Confirmation of Two New Viroid Species

2.6. RT‒PCR Detection of Viruses and Viroids

3. Results

3.1. HTS Data

3.1.2. Known Viruses and Viroids that Infect Opuntia

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis and Genetic Diversity of the Detected Viruses

3.2.1. Opuntia Virus 2 (Genus Tobamovirus)

3.2.2. Cactus Carlavirus 1 (Genus Carlavirus)

3.2.3. Opuntia Potexvirus A (Genus Potexvirus)

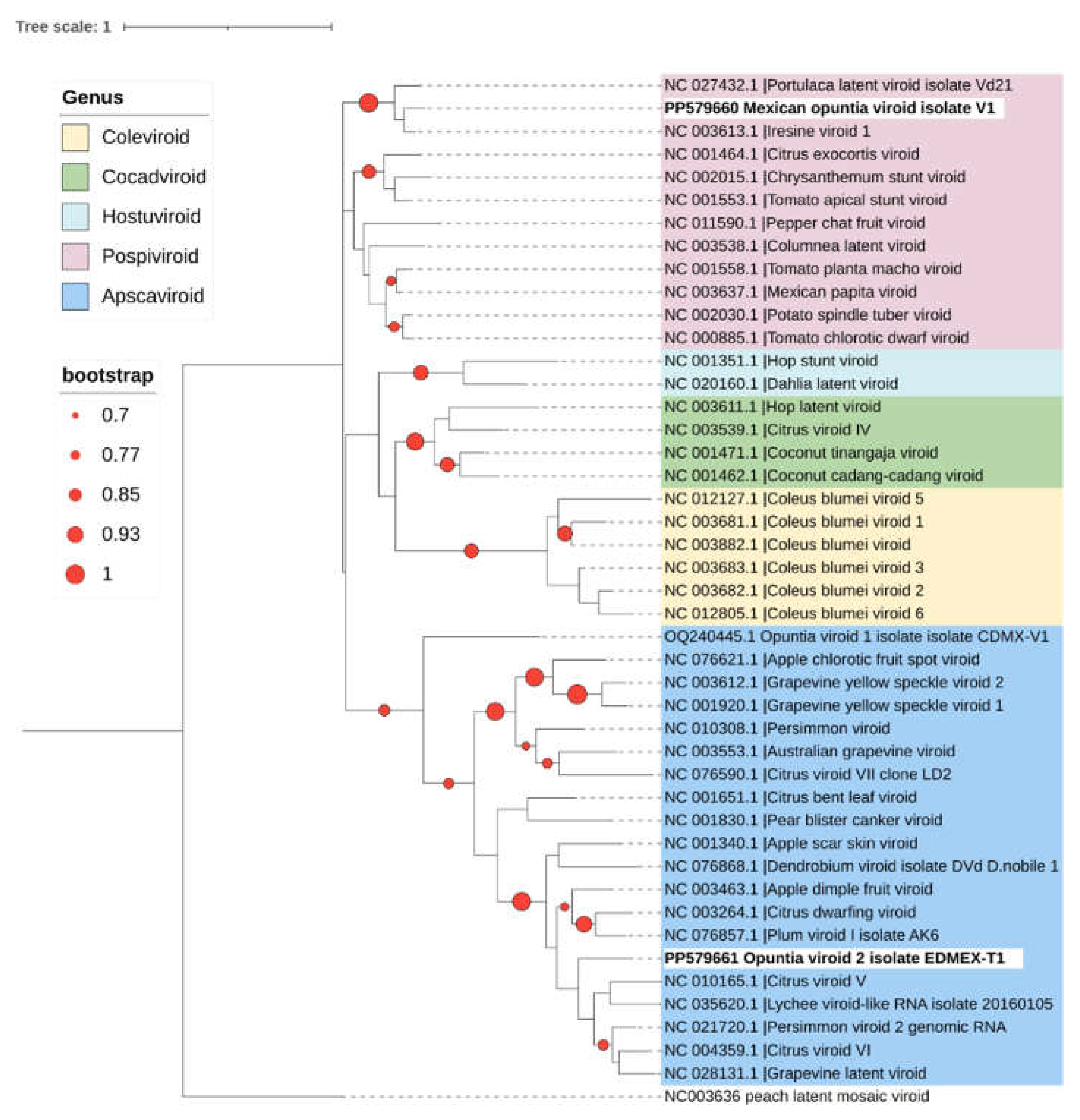

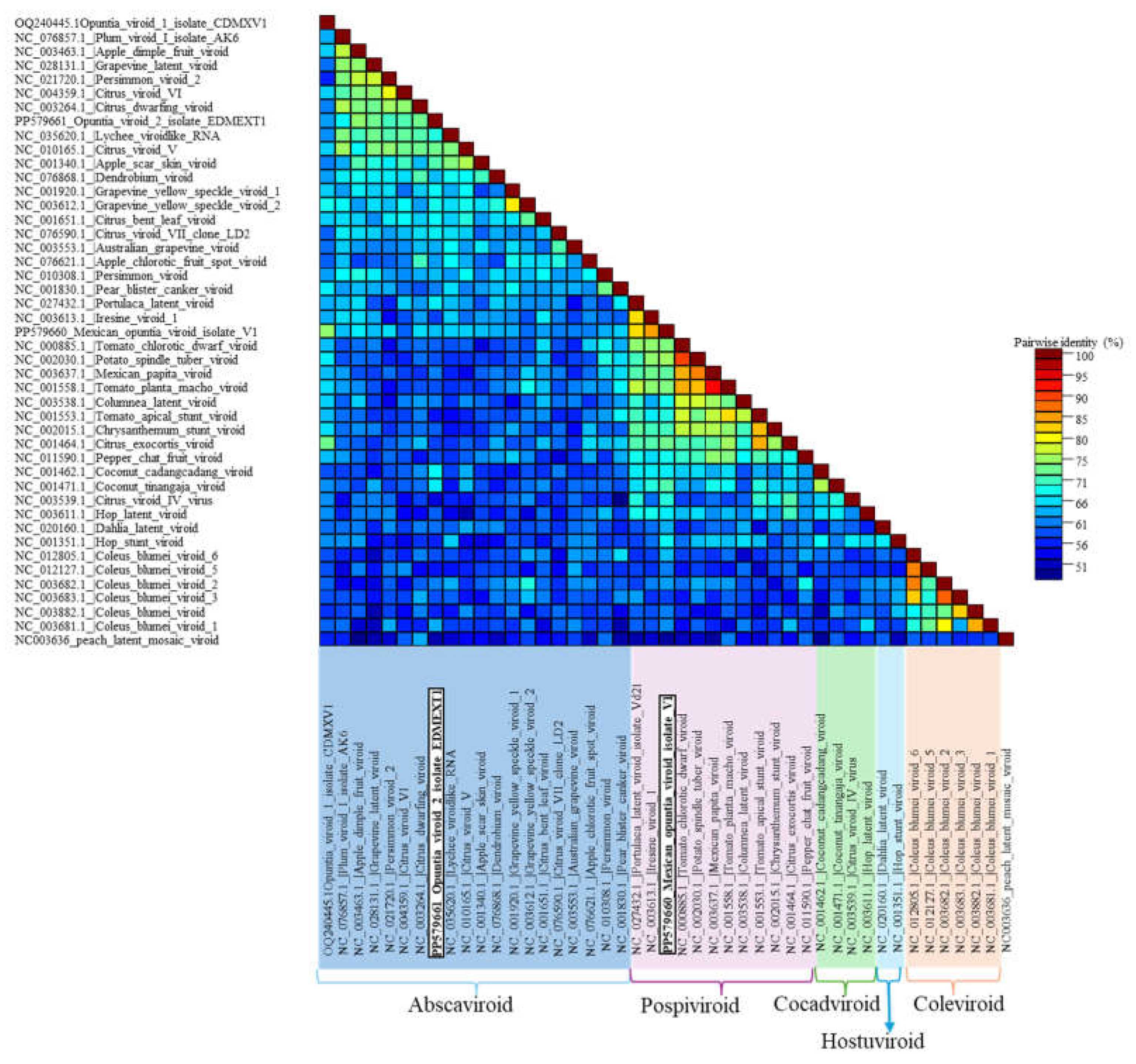

3.2.4. Opuntia Viroid 1 (Putative Genus Apscaviroid)

3.3. Description of Two New Viroid Species

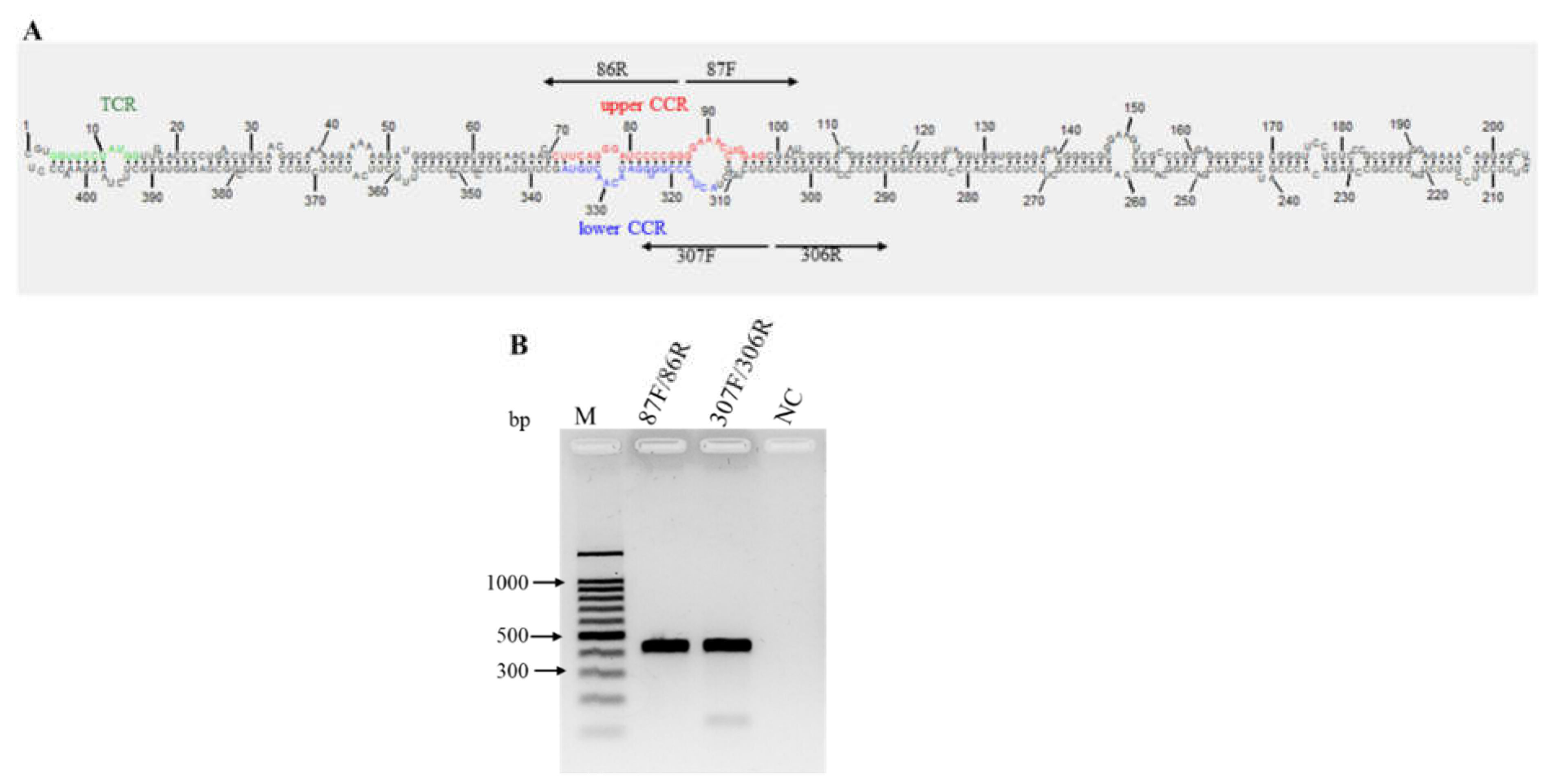

3.3.1. Opuntia viroid 2 (Genus Apscaviroid)

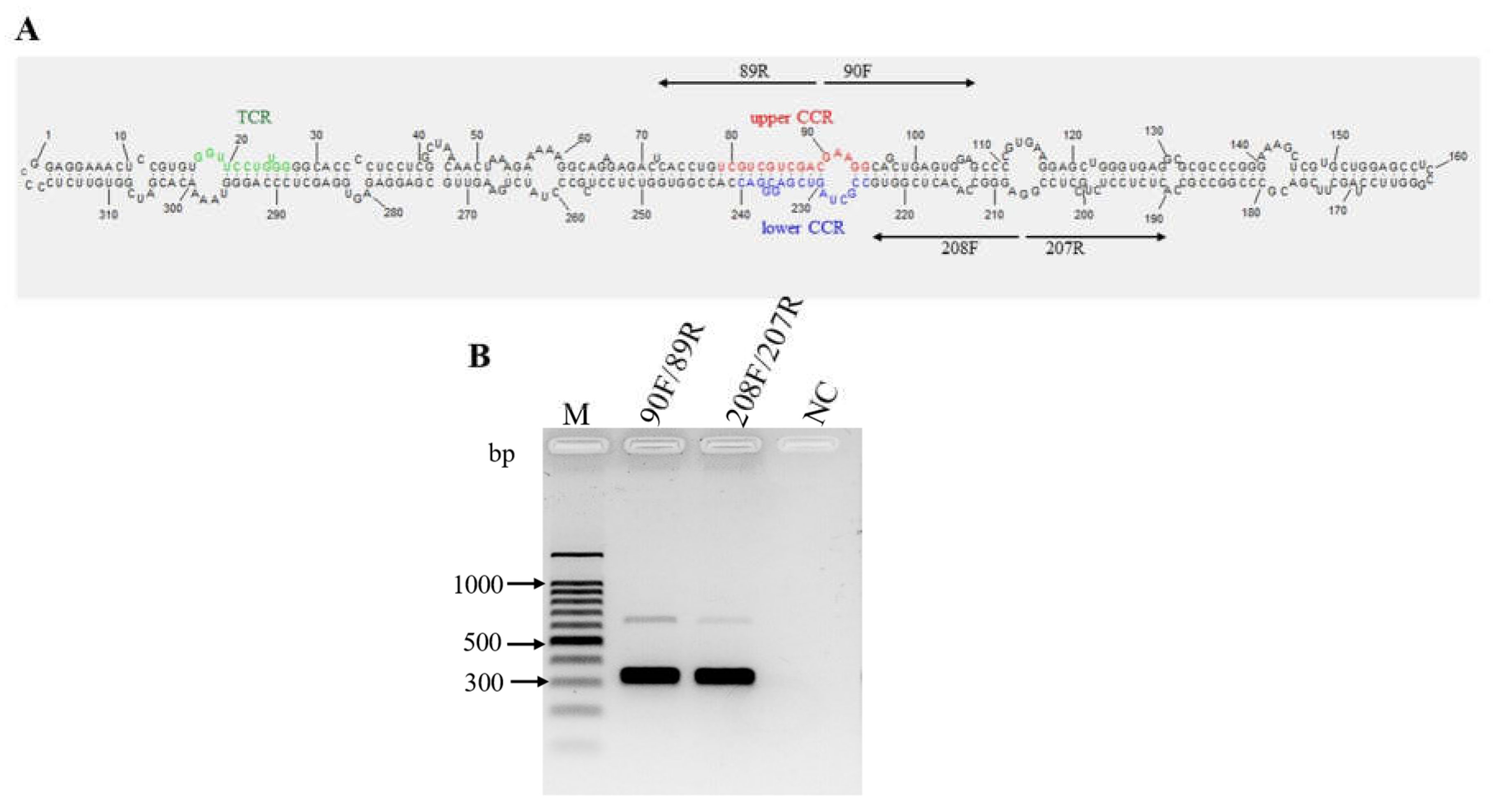

3.3.2. Mexican Opuntia Viroid (Genus Pospiviroid)

3.4. Relative Abundance of Viruses and Viroids Detected by HTS in the Eastern Nopal-Producing Area of the State of Mexico

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griffith, M.P. The Origins of an Important Cactus Crop, Opuntia Ficus-Indica (Cactaceae): New Molecular Evidence. Am. J. Bot. 2004, 91, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobel, P.S. Cacti: Biology and Uses; University of California Press, 2002.

- Le Houérou, H.N. The Role of Cacti (Opuntiaspp.) in Erosion Control, Land Reclamation, Rehabilitation and Agricultural Development in the Mediterranean Basin. J. Arid Environ. 1996, 33, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Valdez, C.A. “Nopalitos” Production, Preoceáing and Marketing.

- Rodríguez, L.C.; Faúndez, E.; Seymour, J.; Escobar, C.A.; Espinoza, L.; Petroutsa, M.; Ayres, A.; Niemeyer, H.M. Biotic Factors and Concentration of Carminic Acid in Cochineal Insects (Dactylopius Coccus Costa) (Homoptera: Dactylopiidae). Agric. Téc. 2005, 65, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIAP. Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Agrícola; SIAP. Mex. City Mex. 2023.

- Villamor, D.E.V.; Keller, K.E.; Martin, R.R.; Tzanetakis, I.E. Comparison of High Throughput Sequencing to Standard Protocols for Virus Detection in Berry Crops. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villamor, D.E.V.; Ho, T.; Al Rwahnih, M.; Martin, R.R.; Tzanetakis, I.E. High Throughput Sequencing For Plant Virus Detection and Discovery. Phytopathology® 2019, 109, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, R.; Malan, S.S.; Maree, H.J. A Plum Marbling Conundrum: Identification of a New Viroid Associated with Marbling and Corky Flesh in Japanese Plums. Phytopathology® 2020, 110, 1476–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maree, H.J.; Fox, A.; Al Rwahnih, M.; Boonham, N.; Candresse, T. Application of HTS for Routine Plant Virus Diagnostics: State of the Art and Challenges. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado-Ortiz, H.; De La Torre-Almaraz, R.; Sanchez-Navarro, J.A.; Pallas, V. Identification and Genomic Characterization of a Novel Tobamovirus from Prickly Pear Cactus. Arch. Virol. 2020, 165, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Acosta, C.; Ochoa-Martínez, D.L.; Rojas-Martínez, R.I.; Nava-Díaz, C.; Valverde, R.A. Virome of the Vegetable Prickly Pear Cactus in the Central Zone of Mexico. Rev. Mex. Fitopatol. Mex. J. Phytopathol. 2023, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenele, R.S.; Bhaskara, A.; Cobb, I.N.; Majure, L.C.; Salywon, A.M.; Avalos-Calleros, J.A.; Argüello-Astorga, G.R.; Schmidlin, K.; Roumagnac, P.; Ribeiro, S.G.; Kraberger, S.; Martin, D.P.; Lefeuvre, P.; Varsani, A. Identification of the Begomoviruses Squash Leaf Curl Virus and Watermelon Chlorotic Stunt Virus in Various Plant Samples in North America. Viruses 2021, 13, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenele, R.S.; Salywon, A.M.; Majure, L.C.; Cobb, I.N.; Bhaskara, A.; Avalos-Calleros, J.A.; Argüello-Astorga, G.R.; Schmidlin, K.; Khalifeh, A.; Smith, K.; Schreck, J.; Lund, M.C.; Köhler, M.; Wojciechowski, M.F.; Hodgson, W.C.; Puente-Martinez, R.; Van Doorslaer, K.; Kumari, S.; Vernière, C.; Filloux, D.; Roumagnac, P.; Lefeuvre, P.; Ribeiro, S.G.; Kraberger, S.; Martin, D.P.; Varsani, A. A Novel Divergent Geminivirus Identified in Asymptomatic New World Cactaceae Plants. Viruses 2020, 12, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Torre-Almaraz, R.; Salgado-Ortiz, H.; Salazar-Segura, M.; Pallas, V.; Sanchez-Navarro, J.A.; Valverde, R.A. First Report of Schlumbergera Virus X in Prickly Pear (Opuntia Focus-Indica) in Mexico. PLANT Dis. 2016, 100, 1799–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Torre-Almaraz, R.; Salgado-Ortiz, H.; Salazar-Segura, M.; Pallas, V.; Sanchez-Navarro, J.A.; Valverde, R.A. First Report of Rattail Cactus Necrosis-Associated Virus in Prickly Pear Fruit (Opuntia Albicarpa Scheinvar) in Mexico. PLANT Dis. 2016, 100, 2339–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast Gapped-Read Alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Robinson, J.T.; Mesirov, J.P. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): High-Performance Genomics Data Visualization and Exploration. Brief. Bioinform. 2013, 14, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Conesa, A.; García-Alcalde, F. Qualimap 2: Advanced Multi-Sample Quality Control for High-Throughput Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Serio, F.; Owens, R.A.; Li, S.-F.; Matoušek, J.; Pallás, V.; Randles, J.W.; Sano, T.; Verhoeven, J. Th. J.; Vidalakis, G.; Flores, R.; Consortium, I.R. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Pospiviroidae. Journal of General Virology 2021, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhire, B.M.; Varsani, A.; Martin, D.P. SDT: A Virus Classification Tool Based on Pairwise Sequence Alignment and Identity Calculation. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e108277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuker, M. Mfold Web Server for Nucleic Acid Folding and Hybridization Prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3406–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rijk, P.; Wuyts, J.; De Wachter, R. RnaViz 2: An Improved Representation of RNA Secondary Structure. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 299–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT Online Service: Multiple Sequence Alignment, Interactive Sequence Choice and Visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast Model Selection for Accurate Phylogenetic Estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shi, C.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Ye, J.; Yu, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Fang, L.; Chen, Q. SOAPnuke: A MapReduce Acceleration-Supported Software for Integrated Quality Control and Preprocessing of High-Throughput Sequencing Data. GigaScience 2018, 7, gix120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Serio, F.; Flores, R.; Verhoeven, J. Th. J.; Li, S.-F.; Pallás, V.; Randles, J.W.; Sano, T.; Vidalakis, G.; Owens, R.A. Current Status of Viroid Taxonomy. Arch. Virol. 2014, 159, 3467–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviña-Padilla, K.; Zamora-Macorra, E.J.; Ochoa-Martínez, D.L.; Alcántar-Aguirre, F.C.; Hernández-Rosales, M.; Calderón-Zamora, L.; Hammond, R.W. Mexico: A Landscape of Viroid Origin and Epidemiological Relevance of Endemic Species. Cells 2022, 11, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Soriano, J.P.; Galindo-Alonso, J.; Maroon, C.J.; Yucel, I.; Smith, D.R.; Diener, T.O. Mexican Papita Viroid: Putative Ancestor of Crop Viroids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996, 93, 9397–9401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo Carabez, J.R.; Téliz Ortiz, D.; Vallejo Pérez, M.R.; Beltrán Peña, H. The Avocado Sunblotch Viroid: An Invisible Foe of Avocado. Viruses 2019, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadbent, L. Epidemiology and Control of Tomato Mosaic Virus. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1976, 14, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Grinstead, S.; Kinard, G.; Wu, L.-P.; Li, R. Molecular Characterization and Detection of Two Carlaviruses Infecting Cactus. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 1873–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Virus/Viroid | Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Amplicon (bp) | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opuntia potexvirus A | OPVA-RepF | AAGCTCGCAGCATCCATCAA | 482 | Viral replicase |

| Opuntia potexvirus A | OPVA-RepR | GGGTGAAGGGACGGTAGTTG | ||

| Cactus carlavirus 1 | CCV-1F | AATGGGCGCCTTTAGGTTCA | 559 | Capsid protein |

| Cactus carlavirus 1 | CCV-1R | AATTCCAAGCTCCCGTCAGG | ||

| Opuntia virus 2 | OV2-F | CTTCCAAGAGTTCTAGCGCCT | 609 | Capsid protein |

| Opuntia virus 2 | OV2-R | ACCTGCAGGATTACCACCAC | ||

| Opuntia viroid I | OPVd_IF | GACGGAGCGTCGAGAAGTAG | 412 | Complete genome |

| Opuntia viroid I | OPVd_IR | GCC GGC GCC GAA GCC CGA G | ||

| Opuntia viroid II | Opuntia_viroid_II_307F | TCTGGCTACTACCCGGTGG | 407 | |

| Opuntia viroid II | Opuntia_viroid_II_306R | GCGACCAGCAGGGGAAG | Complete genome | |

| Opuntia viroid II | Opuntia_viroid_II_86R | CCGGGGATCCCTGAAG | 407 | |

| Opuntia viroid II | Opuntia_viroid_II_87F | GGAAACCTGGAGCGAACTC | Complete genome | |

| Opuntia viroid III | Opuntia_viroid_III_F90 | GAAGGCAGCTGAGTGGAG | 319 | |

| Opuntia viroid III | Opuntia_viroid_III_R89 | GTCGACGACGACAGGTGA | Complete genome | |

| Opuntia viroid III | Opuntia_viroid_III_208F | AGGGCCACACTCGGTG | 319 | Complete genome |

| Opuntia viroid III | Opuntia_viroid_III_207R | CCGGAGGCAGAGGAGAG | ||

| Municipality | Location | Type of Nopal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit | Nopal Vegetable | Xoconostle | wild prickly pear cactus | ||

| Axapusco | Cuautlacingo | 3 | 38 | 0 | 0 |

| Axapusco | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Temascalapa | Santa Ana Tlachiahualpa | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Nopaltepec | San Felipe Teotitlán | 20 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Teotihuacán | Teotihuacán | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 37 | 43 | 4 | 2 | |

| HTS Sample | Virus/Viroid Detected* | GenBank Accession Number | Isolation | Genome Segment | Reference Sequence Accession Number (NCBI GenBank) | % Identity with Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nopal vegetable | CCV-1 | PP579657 | EM_C2 | complete | KU854930.4 | 92.14% |

| OPV- A | PP579658 | EM_A2 | complete | OQ240443.1 | 85.50% | |

| OV2 | PP579659 | EM_T2 | complete | NC_040685.2 | 98.98% | |

| OVd 1 | PP579662 | EDMEX-V1 | complete | OQ240445.1 | 98.54% | |

| prickly pear cactus | CCV-1 | PP579654 | EM_C1. | **RdRp | KU854930.4 | 88.83% |

| OPV-A | PP579655 | EM_A1 | complete | OQ240443.1 | 90.16% | |

| OV2 | PP579656 | EM_T1 | complete | NC_040685.2 | 98.98% |

| HTS Sample | Viroid | GenBank Accession Number | Isolate | Closest Viroid in BLASTn Analysis | Reference Sequence, Accession Number (NCBI GenBank) | % Identity with Reference (% Query Cover) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nopal vegetable | Mexican opuntia viroid | PP579660 | V1 | Iresine viroid 1 | OM108483.1 | 83.33 (99) |

| prickly pear cactus | Opuntia viroid 2 | PP579661 | EDMEX-T1 | Grapevine latent viroid | MG770884.1 | 82.81 (38) |

| Viroid* | TCR | CCR Upper Strand | CCR Lower Strand |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOVd (PP579660.1) | GGUUCCUGUGG | CUUCAGGGAUCCCCGGGGAAACCUGGAG | ACUACCCGGUGGAUACAACUGUAGCU |

| PSTVd (NC_002030.1) | GGUUCCUAUGG | CUUCAGGGAUCCCCGGGGAAACCUGGAG | ACUACCCGGUGGAAACAACUGAAGCU |

| IrVd-1 (NC_003613.1) | GGUUCCAAUGG | CUUCAGGGAUCCCCGGGGAAACCUGGAG | ACUACCCGGUGGAUACAACUGUAGCU |

| OVd-2 (PP579661.1) | GGUUCCUGUGG | UCGUCGUCGACGAAGG | CCGCUAGUCGAGCGGAC |

| ASSVd (NC_001340) | GGUUCCUGUGG | UCGUCGUCGACGAAGG | CCGCUAGUCGAGCGGAC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).