1. Introduction

The World Health Organization defines adolescence as the period of life between childhood and adulthood, ages 10-19 years. Around 1.2 billion people, or 1 in 6 of the world’s population, are adolescents aged 10 to 19 (1). The 2018 end of year population statistics for Jamaica, reported 442,808 adolescents 10-19 years old; 56.7% of this age band is comprised of children 10-15 years old (251,072), these younger adolescents represent 9.2% of the Jamaican population (2).

Adolescence is a period of rapid growth and development and risk-taking is part and parcel of this phase of life. Younger adolescents may lack the ability to fully appreciate medium and long term consequences as their prefrontal cortex continues to develop (3) and this may result in suboptimal decision making. Adolescents may therefore engage in risky health behaviours especially if positive social and environmental factors are not present to mitigate against the negative consequences. These social and environmental factors are sometimes termed resiliency factors and include having a nuclear family structure, self-efficacy and positive role models (4).

In some settings, some physical intimacy in early adolescence may be considered normative, with the majority of younger adolescents engaging in kissing or other intimate contact. (5). Early sexual initiation/debut, which has also been defined as sexual intercourse before the age of fourteen years (6), increases the risk of adolescents engaging in risky sexual behaviours including unprotected sex and multiple sex partners, thereby increasing the probability of contracting sexually transmitted diseases, and having unwanted pregnancies.(7–9) Further, adolescents engaging in risky sexual practices are twice as likely to report depressive symptoms(10).

While most Jamaican adolescents are well-adjusted and do not engage in risky behaviour, the age of sexual initiation is early. Peltzer et al. reports 1 in 4 adolescents in the Caribbean initiate sex before age 15 years.(11). The Reproductive Health Survey of 2003 reported that amongst 15- 24 year olds in Jamaica, the mean age of sexual initiation was 13.5 years for males and 15.8 years for females and the subsequent survey in 2008 reports an increase in the mean age of sexual initiation for that age group at 16.1 years for women and 14.5 years for men. (12, 13) Jarrett et al. surveyed 837 Jamaican adolescents and young adults ages 15-24 years and found the average age of sexual initiation was 14.7 years and of these persons, many of them reported engaging in risky sexual practices such as having multiple sex partners (44.4%) and not consistently using condoms (58.8%) during their sexual encounters A high proportion (44.4%) also engage in transactional sex.(14). Ma et al. however highlighted that strength of character which is present in most adolescents was related to less sexual activity and substance use (8).

Jamaica is currently ranked as having the fourth highest adolescent fertility rate within the Caribbean (15). Reports also indicate that while the adolescent fertility rate is on the decline, it has remained relatively high, at 54.4 in 2016, in comparison to the global rate of 44.6 (15).While there has been noteworthy decrease in the fertility rate above age 15years this has not been reflected in the younger adolescents (16). The number of unplanned pregnancies in the adolescent population in Jamaica has decreased but has remained higher than other Caribbean countries, this may largely be attributed to lack of access to contraception, particularly for the females (12, 17). A significant proportion of adolescents, girls more so than boys, report their first sexual encounter was forced or coerced (18–20).

The Reproductive Health Survey 2008 (13) reported that in the 15-24 years age band, 49% of females and 4% of males reported coerced first sex. In this group, the forced sexual intercourse was associate with being under the age of fourteen years for females but not of for males (13). There is a disproportionate gender differential among adolescents 10-14 years; within this age group, girls are at a two times higher risk of contracting HIV than boys. Adolescent girls are also three times more likely than boys to contract a HIV infection (21)

In the context of resiliency factors, which is defined by varying authors ((22–26) but can be coined as individual assets that improve a person’s outcomes in the face of adversity. While the literature shows that resiliency factors differ by gender (27) it has also shown that for youth and adolescents there are several facets that improve outcomes across genders, these include factors such as self-confidence/self-efficacy (28) supportive family and social environment (24,29). The social component is integral at this developmental stage of the adolescent’s life as it helps to provide a buffer to the conditions that may increase risky behaviours. In a Canadian study of school youth, Philips et al. found that youth with high resilience had less risk taking behaviours and were less likely to report early sexual activity (28). Some factors associated with early sexual initiation or debut are lack of parental monitoring and connectedness, (27) and not living with biological parents (11,30). Some of the factors associated with early sexual debut in Caribbean youth were found to be male gender, and lack of parental or guardian attachment (11)

The Youth Risk and Resiliency Behaviour Jamaican Survey 2005 had several objectives in describing the health and demographic profile of youth, one objective was to determine the context of reproductive health of adolescents 10-15 years in Jamaica including the magnitude and determinants of sexual activity (18). Determinants were categorized as risk and resiliency factors. There is a paucity of research or data on preadolescents in the Jamaican context. While the health system collects a wealth of data on children from birth to five years of age there is limited data on children from six years to adulthood. The 2005 Youth Risk and Resiliency Survey was therefore re-explored to provide data This paper presents the findings of the reproductive health component of the wider study and explores these determinants.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was a nationally representative cross-sectional, interviewer administered school-based survey conducted in all parishes of Jamaica. Children ages 10-15 years who were attending primary or secondary school were eligible to participate. The sample frames were the listing of all public primary and secondary schools from the Ministry of Education Youth and Culture and the class registers for the grades with students within the 10-15 years old age group. A multi-stage sampling process was employed, involving a random selection of schools proportional to the number of schools per education region followed by a random selection of students within the grades with the required age groups. A minimum of 24 students per school was selected.

2.1. Sample Size Calculation

Using the rate of tobacco use within this age group as 19%, a 95% confidence level, 80% power, an error of +2% and a refusal rate of 10%, a sample size of 2,800 subjects was required. (31)

2.2. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the Ministry of Health’s Ethics Committee. Consent forms were sent to the parents of the children selected to participate in the study. Once consent was obtained from the parent, assent was then sought of the child. A referral process was instituted to treat and support children who reported sexual abuse and other extreme risky behaviours or events (for example suicidal ideation).

2.3. Instruments

The questionnaire was compiled from validated questions from previous surveys on the same age group of Jamaican children. These surveys included:-

The global youth tobacco survey 13-15 years (31)

The Caribbean Adolescent Health Survey 10-18 years (32) (33)

Global School Health Survey (19)

Healthy Lifestyles Survey 2000 (34)

The Jamaican Cohort Study, 2002 (35)

Patterns of Drug Use in Secondary Schools (36)

The questionnaire comprised of thirteen modules, including demographic information, resiliency and sexual behaviour among others. A full listing of the modules of the questionnaire was previously reported in the technical report (18). Validation of the final questionnaire was done during the pre-testing phase of the project. This paper focuses on the sexual behaviour, demographic profile and resiliency modules.

2.4. Definition of Resiliency Factors

Resiliency was measured using seven variables considered protective factors inside the home, which we defined as supportive connections with others who serve as prosocial models and support healthy development. This was measured using four categories:

Care/interest –Adolescents were asked if there was an adult in the home who was interested in them, who talked with them about their problems

Attention –there was someone in the home who was never too busy to pay attention to them

Listening- there was someone who listened to what they had to say.

Religiosity was defined as an increased frequency of church attendance.

The responses to these questions ranged from “never” to” always true”. Each response was assigned a score ranging from zero (never) to 5 (always true). These scores were summated to develop a resiliency score.

2.5. Risk Factors

The risk factors included indicators of community disorganization which were defined as: drug use, presence of garbage on the streets, presence of prostitutes in the community. A variable measuring community disorganization was created using the following questions:

Which of the following is usually present in your community.

Garbage on the street, writings on the walls, abandoned cars, unemployed youth on the street, gangs on the street, prostitutes or sex workers, gunmen, people selling drugs and people using drugs. The responses from these variables were used to calculate a community disorganization score.

Sexual Activity was defined using the follow variables:

Age at sexual initiation- The age at which students had penetrative sexual intercourse from the first time.

Early age of sexual initiation—If initiation occurred before age fifteen years

Sexually active- Students who claimed to have engaged in sexual activity at least once prior to the study.

Other variables examined were frequency of non-coital sex and coital sex and non-use of condoms at last sex.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Summary statistics of the demographics are presented as proportions with 95% confidence intervals. Bivariate analyses were performed to assess the level of association between the dependent variable: Sexual initiation and the independent variables. Variables which demonstrated significant relationships in the bivariate analyses were included in the initial logistic regression model. In the final model, variables with P-value <0.05 were selected. The adequacy of the final model was sought with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. These multiple regression analyses were conducted to determine the predictors of sexual initiation in this target population. Survival analysis was used to compare the time to sexual initiation by males and females with national data.3.

3. Results

3.1. Profile of Participants

3003 children were surveyed, 1,422(47.4%) males and 1,581 (52.6%) females. The mean age (SD) overall was 12.5 (1.6) years, males 12.5 (1.6) and females 12.4 (1.6) Fifty-two percent came from urban schools. More than half of the youth reported seeing garbage on the street and unemployed youth loitering on the street. More than a third reported abandoned cars and drug users on the street. One in ten youth reported living in a disorganized community with significant gender differences (p=0.002). There were significant differences in neighborhood/community disorder by school location with more community disorder reported by students attending urban schools.

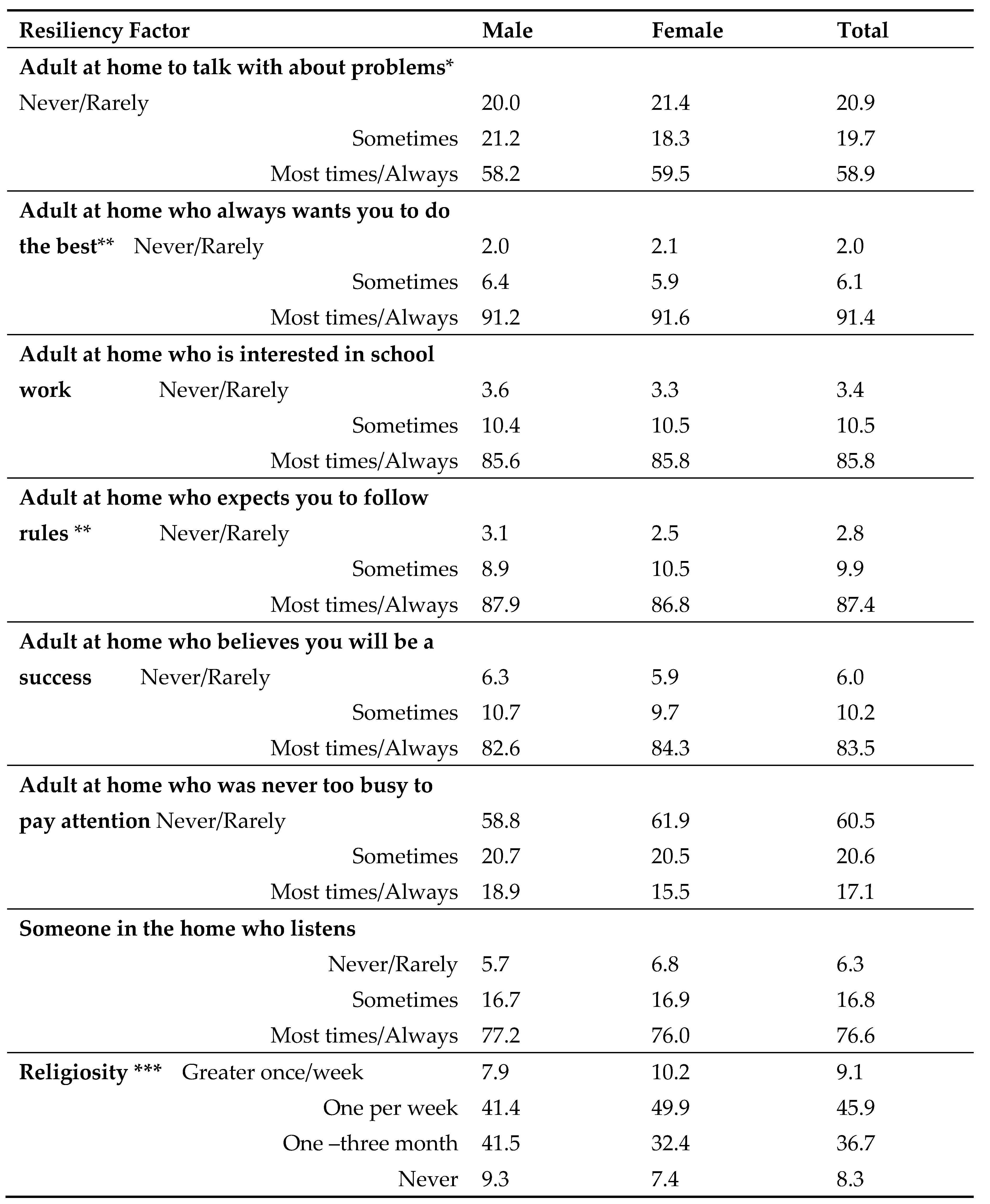

Table 1.1.

The majority of respondents reported having someone in the home who was interested in their school work, who want them to do their best and thought they would be a success (> 80%). Fewer students reported having someone in the home who listens to them (77%), who was never too busy to pay attention to them (68%) and someone to talk to about their problems (59%). A little more than half of the respondents (55%) reported attending church at least once per week, with significant gender differences in church attendance (p<0.001).

Table 1.2

3.2. Non-Coital Sex

47.7% of boys and 21.7% of girls had kissed or petted someone of the opposite sex. Same sex kissing/petting was reported by 3.0% of boys and 4.7% girls. The percentage of adolescents engaged in non-coital sexual activity increased with age for both males and females. At age 10-12 years, approximately 4% of girls and 17% of boys were engaged in non-coital sexual activity. By age 13-16 years, this figure increased to 13-31% and 26-46% for boys and girls respectively (p<0.001).

3.3. Sexual Intercourse

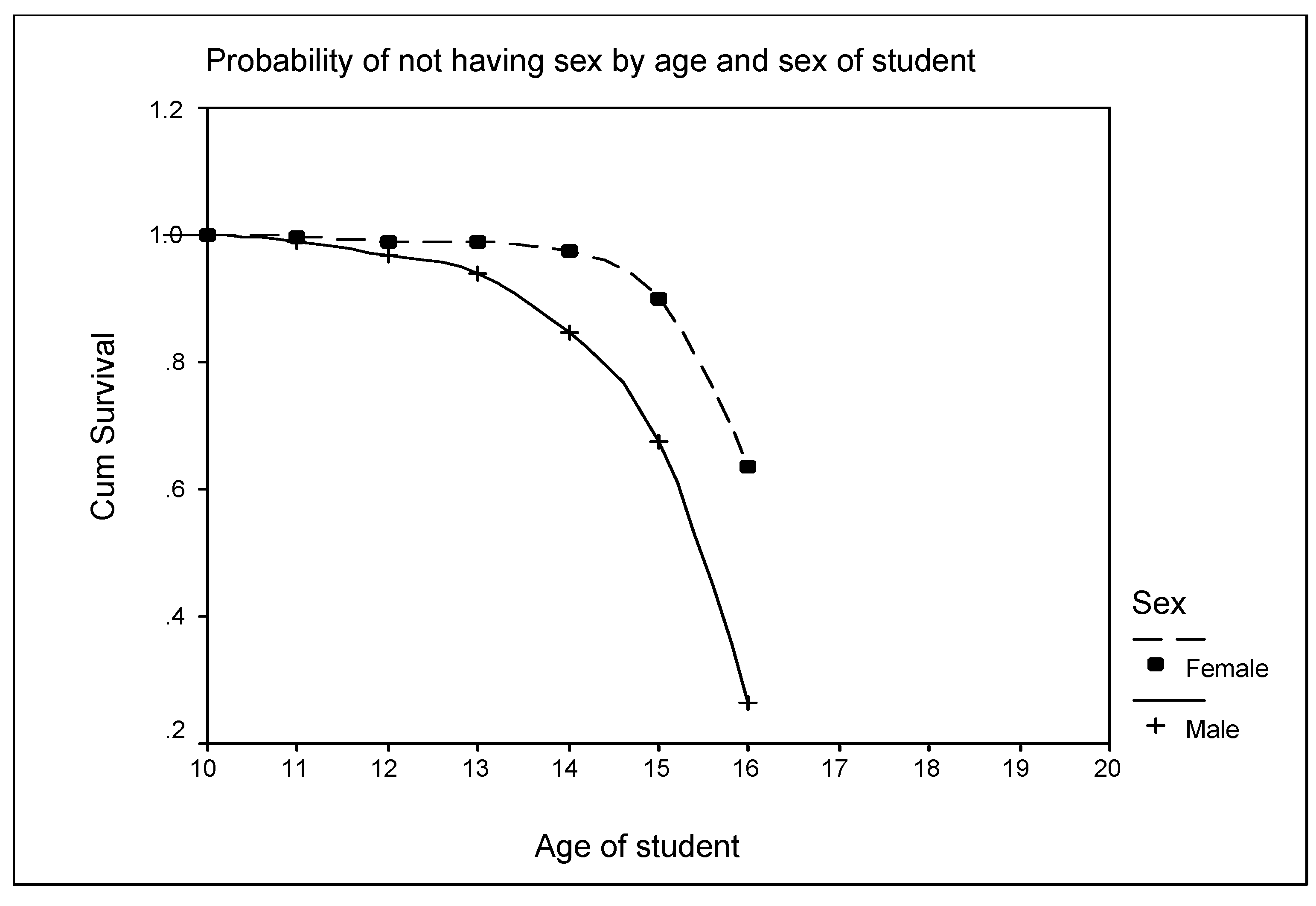

At least one in ten adolescents reported having sexual intercourse (12.8%), with boys four times more likely to do so than girls; 20.9% boys vis-à-vis 5.5% girls. The mean age of first sex was 11.0 (±2.5) years; Males 10.4 (±2.3); Female 12.9 (±2.2) years. (Median age was 10.0±0.14 males and 13.3±0.23 (years) for females). Using survival analysis to determine the probability of not having sex, the median age of first sex was 15.43 years for boys and over 15 years for girls. At age 15 years, the cumulative proportion of those who had not had sex was 0.26 for boys and 0.64 for girls (

Figure 1.1).

3.4. Sexual Intercourse by Age

Involvement in sexual intercourse mirrored that of non-coital sex with significant increase in children having sex by age 13 years. (p<0.001). Overall, the prevalence increased from 3.8-5.5% in the 10-12 years age group and jumped to 13.6-30.6% in the 13-15 years age group.

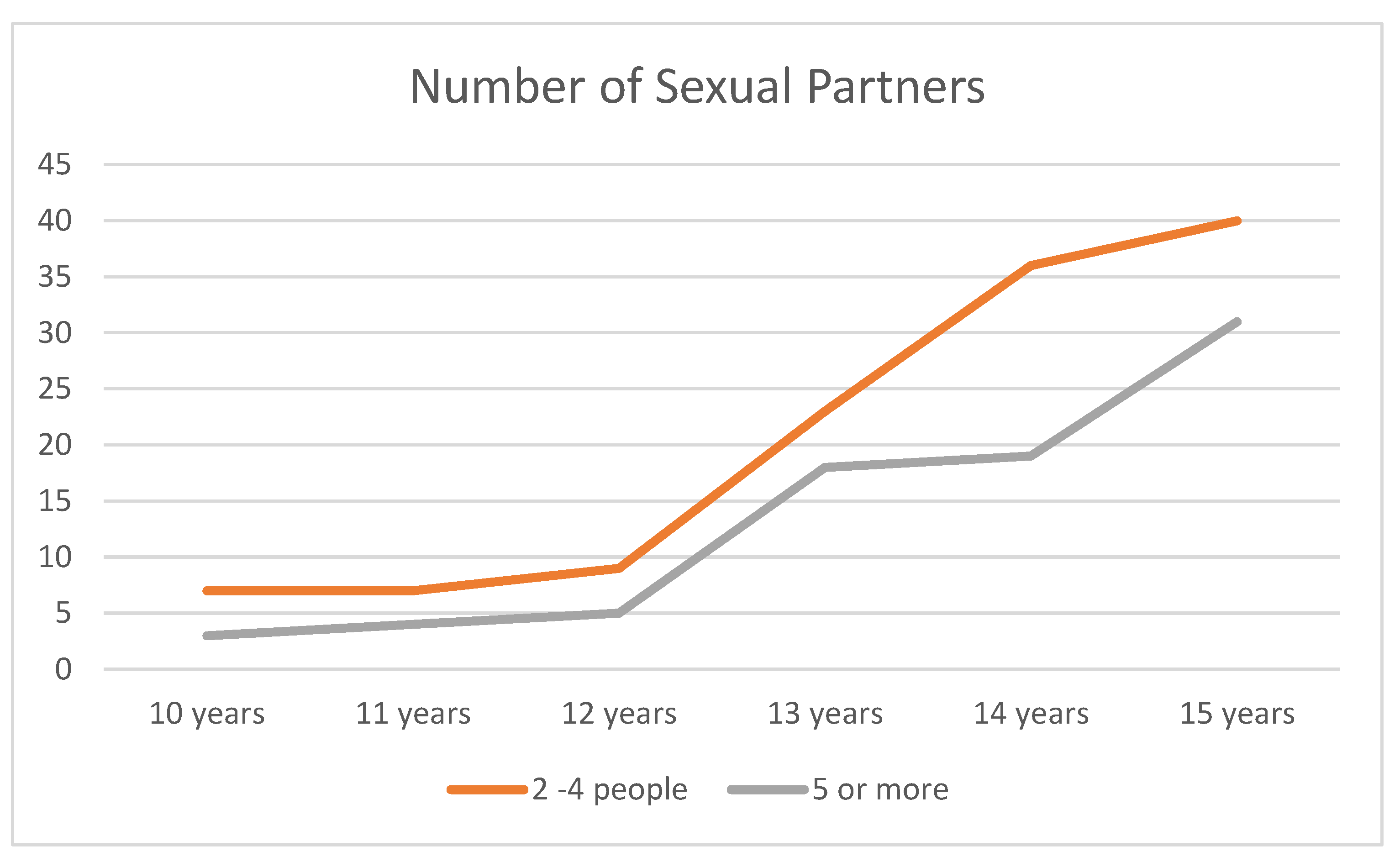

3.5. Number of Sex Partners

Males were significantly more likely to have had 3 or more partners compared to females, with 96.9% of sexually active females reporting 1-2 partners compared with 47.7% of males (p<0.05) (data not shown). Although not statistically significant the number of sexual partners varied with age by age 12 approximately 13% of respondents reported having two or more partners.

Figure 1.2

3.6. Condom Use at Last Sex

Approximately 50% of sexually active males and females used a condom at last sex (68.5% girls, 46.9% boys). Condom use in boys was significantly associated with age (older boys), school type (high school) and location of school (urban).

3.7. How First Sex Occurred

Among those who were sexually active, 76.4% agreed to having sex on their first encounter, 8.9 % did not agree but did nothing and 12.8% were forced. Those reporting forced sex on their first encounter comprised 9.2% of boys and 24.7% girls (p<0.001). We asked respondent of some of the reasons for not using a condom at last sex. Only 28 females reported not using a condom at last sex. The primary reasons given for not using a condom at last sex for the boys were “didn’t think of it” (20.2%) and “not enough time to prepare”. We also asked respondents where they obtained contraception, more than a third (36%) said they purchased at a local shop (Males 36.7%, Female 34.1%). Significantly more males said they obtained from a friend (Males 17.1%, F 4.7%, Total 14.1% p<0.001).

Table 1.3.

Proportion (%) of Jamaican Youth Age 10-15 years reporting sexual behaviour by gender.

Table 1.3.

Proportion (%) of Jamaican Youth Age 10-15 years reporting sexual behaviour by gender.

| Risk Behaviour |

Male |

Female |

Total |

| !Ever had sexual intercourse #

|

20.0 |

5.5 |

12.8 |

| Noncoital sex |

47.7 |

21.7 |

38.1 |

| Forced Sexual Encounter#

|

9.2 |

24.7 |

12.8 |

|

!Two or more sexual partners#

|

67.1 |

21.4 |

56.5 |

|

!Non Condom Use at last sex#

|

53.1 |

31.5 |

48.0 |

3.8. Factors Associated with Sexual Initiation

A multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was done to determine the factors associated with sexual initiation. The model included caring relations in the home, community disorganization, and religiosity, location of school, age and sex. The factors found to be significantly associated with sexual initiation were age, sex, and frequency of church attendance, caring relationships inside the home (protective factors) and community disorganization. The odds of early sexual initiation increased if you were older, male, rarely or never attended church, did not have caring relationships inside the home and if your community lacked organization (

Table 2.1).

Multivariate regression analyses were done to determine the factors within a community which increased the risk of early sexual initiation. The presence of unemployed youth (OR 2.0; 95% CI 1.4-2.9), prostitution (OR 2.32 95% CI 1.6-3.5) and people using drugs within the community (OR 1.6; 95% CI 1.1-2.4) were found to significantly increase the odds of early sexual initiation.

4. Discussion

The results show that early sexual initiation is high among Jamaican early adolescents with 12.8% of the cohort aged 10-15 years reporting ever having sex. The age mean of sexual debut was 11 years and survival analysis data which compares this cohort with national data shows that the median age of sexual debut of 15 years for boys is slightly higher than the national average of 14.5 years; but lower for girls at 15.3 years, where the national average is 16.1 years. These data are consistent with that found in the literature, Kassahin in a study of preparatory and high school children in Ethiopia found that 18% of the cohort had early sexual initiation which was defined as sexual intercourse before the age of 18 years (37). In another study from Nigeria (38) where early sexual debut was defined as sex before age 14 years, 11% of the cohort had early sexual initiation.

Jamaican boys are four times more likely to be involved in sexual activity and to have multiple partners than girls. This is consistent with numerous other studies where the gender differences in sexual practices are significant ((10, 38–40). We found that condom use at last sex was 46.9% in boys and 68.5% in girls with only 21.8% reporting that they use a condom every time within the subset of early adolescents who had ever been sexually active. Approximately one in four girls and one in ten boys reported that their first sexual experience was forced. The proportion of adolescence who reported (“didn’t agree to have sex but did nothing”) was 11% in girls and 8% in boys. This apathy is more likely due to a lack of empowerment, power inequality; poor negotiation skills in these adolescents.

Of note, the primary reasons given for not using a condom at last sex was not having enough time to prepare and didn’t think of it. The wider implication is that adolescents are not sufficiently prepared to responsibly engage in sex. This is in contrast to the reasons given by young adults for inconsistent condom use which in an African population was the need to have a child or to please the partner (41).

The data clearly show the effect of the communities in which these adolescents live on their reproductive health. Adolescents who lived in communities with unemployed youth were more likely to be sexually active and to have early sexual initiation. Bugard and colleagues found that neighborhoods with high levels of social disorder had higher prevalence of sexual initiation, whilst social cohesion promoted delaying of sexual activity in youth (42). In a longitudinal study of African Americans, Tewksbury found that perceived levels of social disorganization influenced the number of sexual partners in youth 15 years and older (43). We found that the number of early adolescents’ sexual partners increased significantly with age, similar to what has been found in older adolescents and young adults in Jamaica and have been reported by other studies. (13, 33,44).

Some protective factors found in this study of early adolescents were religiosity and having caring relationships in the home. These factors were found to reduce early sexual debut by 30% and 15% respectively. Kassahun also found that non-attendance to religious programmes increased the odds of early sexual initiation threefold (37). In a systematic review (4)) also found that religious correlates reduced sexual initiation in girls and Lammers found that high parental expectations were a significant protective factor in boys not girls (30)

5. Conclusions

These findings on the sexual activity of early adolescents reaffirms the positive influence environmental factors such as family connectedness and religious involvement can have on delaying the onset of risk-taking behaviour such as early sexual debut as well as the negative correlates of societal risk factors such as community disorganization. Our findings underscore the need for development of age appropriate educational programmes promoting delayed sexual initiation, responsible sex and consistent condom use and this should start as early as the pre-adolescent age group (<10 years). Empowerment through learned sexual negotiation skills, should be incorporated into the education programme of pre-adolescents to facilitate adolescents embracing their intrinsic power to delay sexual debut and if sexually active to insist on condom use. The societal risks of community disorganization inclusive of youth unemployment also needs to be addressed.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, GG. and AH.; methodology, GG,AG.; software GG.; validation,GG., SRM.; formal analysis,GG.; investigation,GG,AG.; resources,SRM.; data curation, GG.; writing—original draft preparation, GG, SRM.; writing—review and editing,AH, AG.; visualization, AH,AG.; GG,AG All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

“This research was funded by U S Agency for International Development (USAID), grant number GPO-A-00-03-00003-00” and “The APC was funded by all authors ”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ministry of Health Jamaica, Ethics Committee. #05-2654, September 2005

Informed Consent Statement

“Parental Informed consent and assent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.”

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The survey was funded by the USAID through the MEASURE Evaluation project with technical assistance from the National Healthy Lifestyle Project. The study would not have been possible without the collaboration of the Ministry of Education. Special thanks go to the teachers and students who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Adolescents Statistics [Internet]. UNICEF DATA. [cited 2021 Mar 23]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/adolescents/overview/.

- Jamaican Population [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 23]. Available from: https://statinja.gov.jm/Demo_SocialStats/population.aspx.

- Steinberg, L. Risk Taking in Adolescence: New Perspectives From Brain and Behavioral Science. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007, 16, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartland D, Riggs E, Muyeen S, Giallo R, Afifi TO, MacMillan H, et al. What factors are associated with resilient outcomes in children exposed to social adversity? A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e024870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farris C, Akers AY, Downs JS, Forbes EE. Translational research applications for the study of adolescent sexual decision making. Clin Transl Sci. 2013, 6, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgartner JN, Geary CW, Tucker H, Wedderburn M. The Influence of Early Sexual Debut and Sexual Violence on Adolescent Pregnancy: A Matched Case-Control Study in Jamaica. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009, 35, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godeau E, Nic Gabhainn S, Vignes C, Ross J, Boyce W, Todd J. Contraceptive Use by 15-Year-Old Students at Their Last Sexual Intercourse: Results From 24 Countries. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008, 162, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma M, Kibler JL, Dollar KM, Sly K, Samuels D, Benford MW, et al. The relationship of character strengths to sexual behaviors and related risks among African American adolescents. Int J Behav Med. 2008, 15, 319–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnusson BM, Crandall A, Evans K. Early sexual debut and risky sex in young adults: the role of low self-control. BMC Public Health. 2019, 19, 1483. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane S, Younger N, Francis D, Gordon-Strachan G, Wilks R. Risk behaviours and adolescent depression in Jamaica. Vol. 19, International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2014. p. 458–67.

- Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Early Sexual Debut and Associated Factors among In-school Adolescents in Six Caribbean Countries. West Indian Med J. 2015/04/30 ed. 2015, 64, 351–356. [Google Scholar]

- Jamaica Reproductive Health Survey (RHS) 2002-2003. Jamaica: National Family Planning Board; Statistical Institute of Jamaica, Centers for Disease Control; 2004.

- Serbanescu F, Ruiz A, Suchdev D, Stupp P, Goodwin M, Ishida K, et al. Reproductive Health Survey Jamaica, 2008. Kingston: National Family Planning Board; 2010.

- Jarrett SB, Udell W, Sutherland S, McFarland W, Scott M, Skyers N. Age at sexual initiation and sexual and health risk behaviors among Jamaican adolescents and young adults. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22 (Suppl 1), S57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolescent fertility rate (births per 1,000 women ages 15-19) - Jamaica | Data [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 17]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.ADO.TFRT?locations=JM.

- Fertility-young-adolescents-2020.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/fertility/Fertility-young-adolescents-2020.

- Crawford TV, McGrowder DA, Crawford A. Access to contraception by minors in Jamaica: a public health concern. North Am J Med Sci. 2009, 1, 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, K. Jamaica Youth Risk and Resiliency Behaviour Survey. Kingston: Ministry of Health and University of the West Indies; 2005.

- National Council on Drug Abuse. Global School-based Student Health Survey- Jamaica [Internet]. Jamaica: World Health Organization - WHO;US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - CDC; 2017. (Global School-based Student Health Survey). Report No.: JAM_2017_GSHS_v01 Year 2017. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/catalog/644.

- Wilks R, Younger N, McFarlane S, Francis D, Van den Broeck J. Jamaican Youth Risk and Resiliency Behaviour Survey 2006: Community-Based Survey on Risk and Resiliency Behaviours of 15-19 Year Olds [Internet]. MEASURE Evaluation; 2007. Report No.: TR-07-64. Available from: https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/tr-07-64.

- HIV and AIDS in Adolescents [Internet]. UNICEF DATA. [cited 2021 Mar 23]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/adolescents/hiv-aids/.

- Egeland B, Carlson E, Sroufe LA. Resilience as process. Dev Psychopathol. 1993, 5, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fee RJ, Hinton VJ. Resilience in children diagnosed with a chronic neuromuscular disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr JDBP. 2011, 32, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gartland D, Riggs E, Muyeen S, Giallo R, Afifi TO, MacMillan H, et al. What factors are associated with resilient outcomes in children exposed to social adversity? A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e024870–e024870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlson C, Leist-Haynes, S, Smith M, Faith MA, Elkin T, Megason G. Examination of Risk and Resiliency in a Pediatric Sickle Cell Disease Population Using the Psychosocial Assessment Tool 2.0. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012, 37, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutha SS, Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Dev Psychopathol. 2000, 12, 857–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finer LB, Philbin JM. Sexual initiation, contraceptive use, and pregnancy among young adolescents. Pediatrics. 2013/04/01 ed. 2013, 131, 886–891. [Google Scholar]

- Philip P, Kannan S, Parambil N. Community-based interventions for health promotion and disease prevention in noncommunicable diseases: A narrative review. Vol. 7, Journal of Education and Health Promotion. Wolters Kluwer Medknow Publications; 2018. p. 141–141.

- Burgard SA, Lee-Rife SM. Community Characteristics, Sexual Initiation, and Condom Use among Young Black South Africans. J Health Soc Behav. 2009, 50, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammers C, Ireland M, Resnick M, Blum R. Influences on adolescents’ decision to postpone onset of sexual intercourse: a survival analysis of virginity among youths aged 13 to 18 years. J Adolesc Health. 2000, 26, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- THE GLOBAL YOUTH TOBACCO SURVEY, JAMAICA 2000. :59.

- Rinehart, PM. A Portrait of Adolescent Health in the Caribbean 2000. 2000;44.

- Blum RWm. Adolescent Health: Priorities for the Next Millennium. Matern Child Health J. 1998, 2, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks Rainford. Jamaican Healthy Lifestyle Survey 2000. Kingston: Ministry of Health, Jamaica; 2002.

- Samms-Vaughan,Maureen,E. Cognition, educational attainment and behaviour in a cohort of Jamaican children. A comprehensive look at the development and behaviour of Jamaica’s eleven year olds. Jamaica: Planning Institute of Jamaica; 2000.

- Global Youth Tobacco Surveillance, 2000_2007 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 17]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss5701a1.

- Kassahun EA, Gelagay AA, Muche AA, Dessie AA, Kassie BA. Factors associated with early sexual initiation among preparatory and high school youths in Woldia town, northeast Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019, 19, 378. [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Early Sexual Debut and Associated Factors among In-school Adolescents in Six Caribbean Countries. West Indian Med J [Internet]. 2015 Jul 7 [cited 2020 Jun 23]; Available from: https://www.mona.uwi.edu/fms/wimj/article/2088. 2088.

- Durowade KA, Babatunde OA, Omokanye LO, Elegbede OE, Ayodele LM, Adewoye KR, et al. Early sexual debut: prevalence and risk factors among secondary school students in Ido-ekiti, Ekiti state, South-West Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2017, 17, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira Avelar E Silva R, Wijtzes A, van de Bongardt D, van de Looij-Jansen P, Bannink R, Raat H. Early Sexual Intercourse: Prospective Associations with Adolescents Physical Activity and Screen Time. PloS One. 2016, 11, e0158648. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda L, Mash R. Reasons for inconsistent condom use by young adults in Mahalapye, Botswana. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2018, 10, e1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Burgard SA, Lee-Rife SM. Community Characteristics, Sexual Initiation, and Condom Use among Young Black South Africans. J Health Soc Behav. 2009, 50, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewksbury R, Higgins GE, Connor DP. Number of Sexual Partners and Social Disorganization: A Developmental Trajectory Approach. Deviant Behav. 2013, 34, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope Enterprise. What Protects Teenagers From Risk Behaviours? Applying a Resiliency Approach to Adolescent Reproductive Health in Jamaica. Hope Enterprises Ltd. with the Rural Family Support Organization (RFSO) [Internet]. CHANGE Project (USAID; 2001. Available from: https://www.advocatesforyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/storage//advfy/documents/fsjamaica.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).