Submitted:

25 June 2024

Posted:

26 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

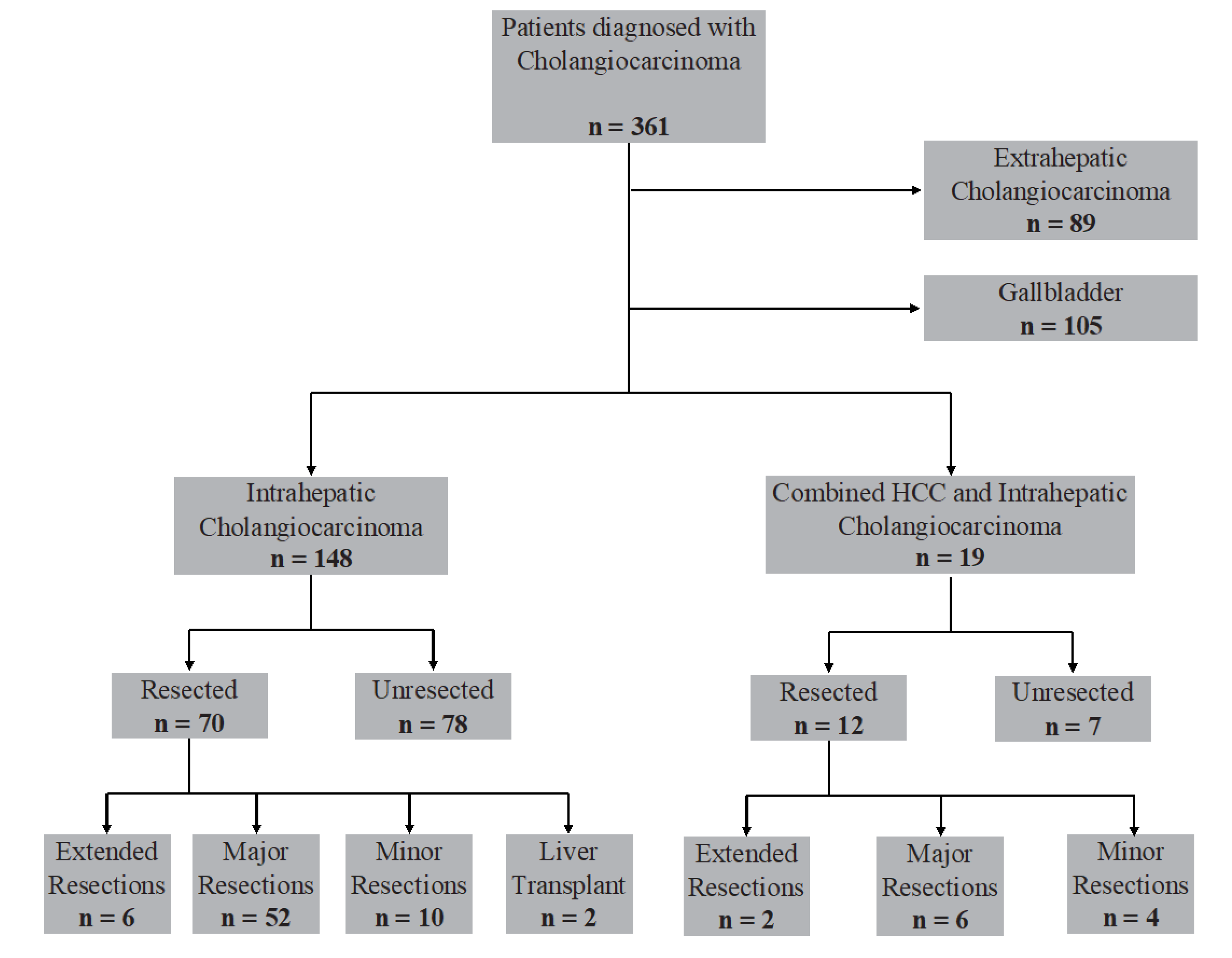

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Study Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

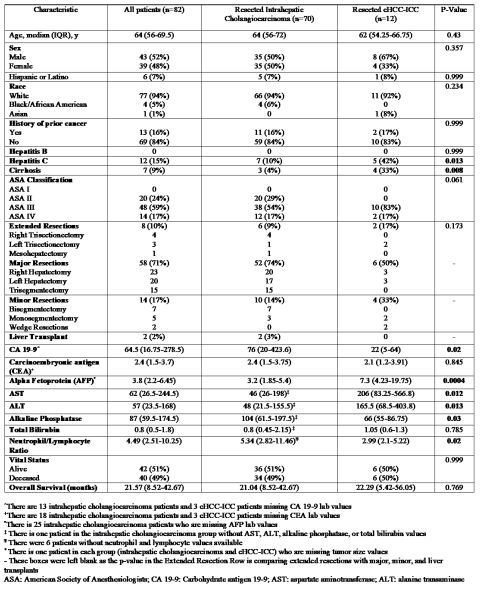

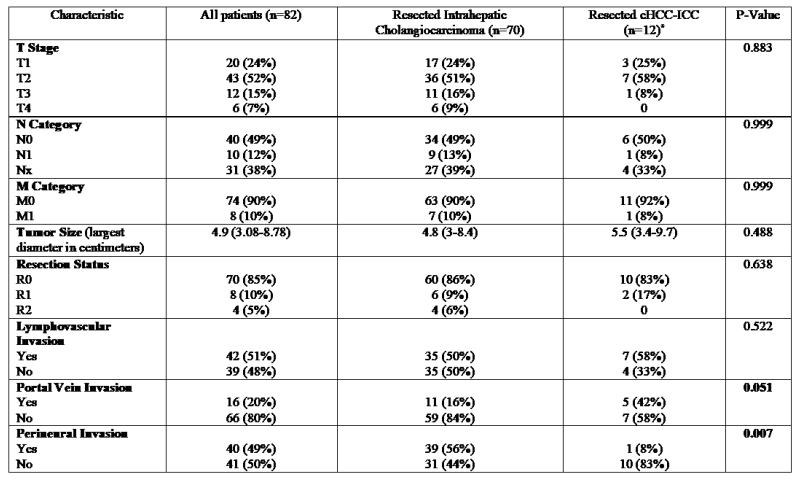

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Disease Characteristics and Tumor Markers

3.3. Surgical Procedural and Histological Data

3.4. Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Treatment

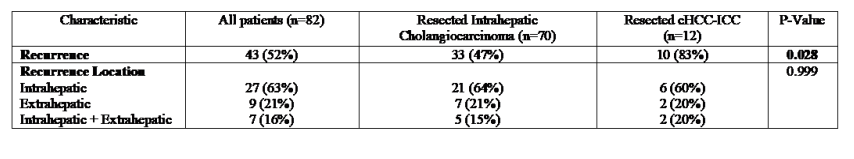

3.5. Tumor Recurrence

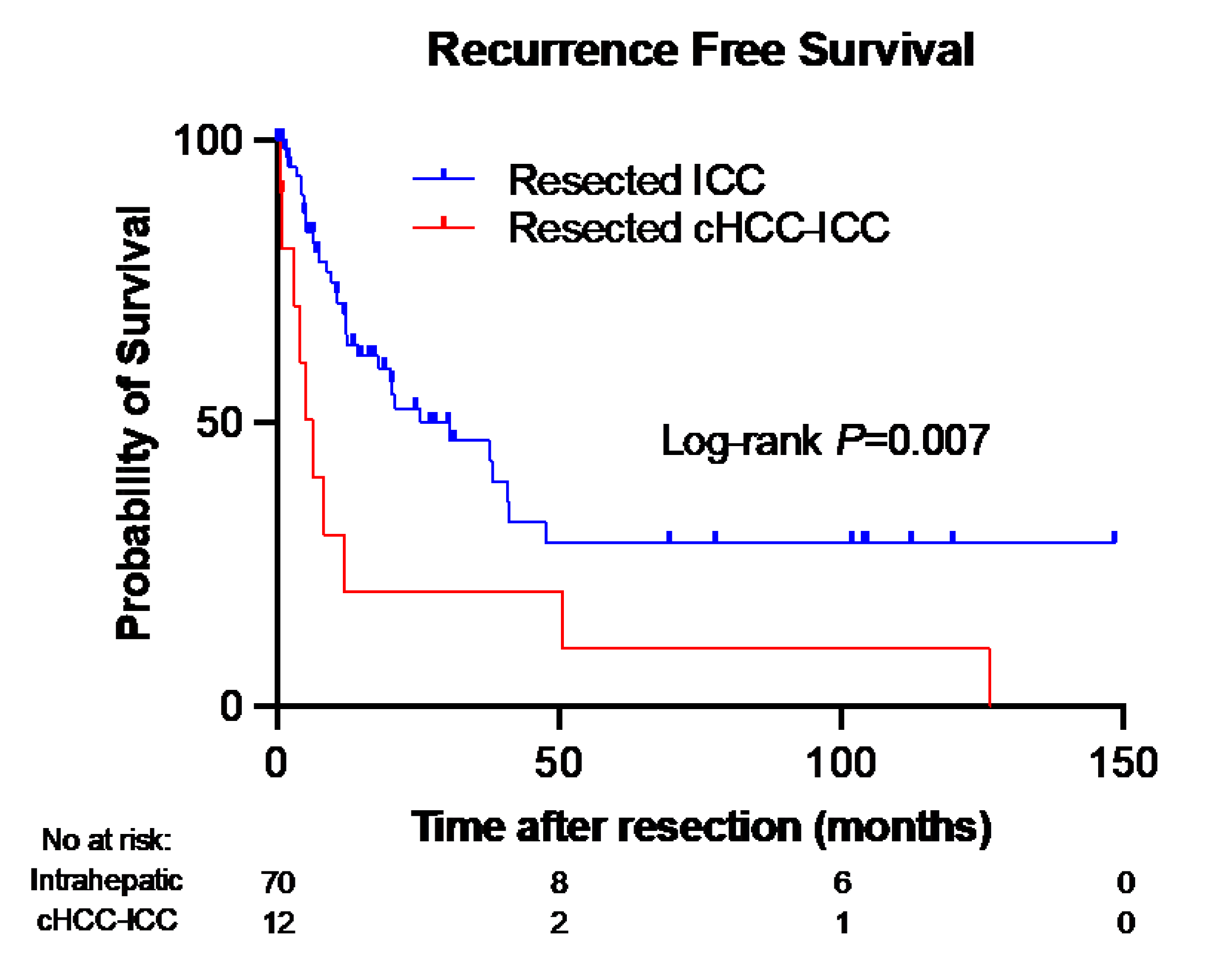

3.6. Recurrence-Free Survival

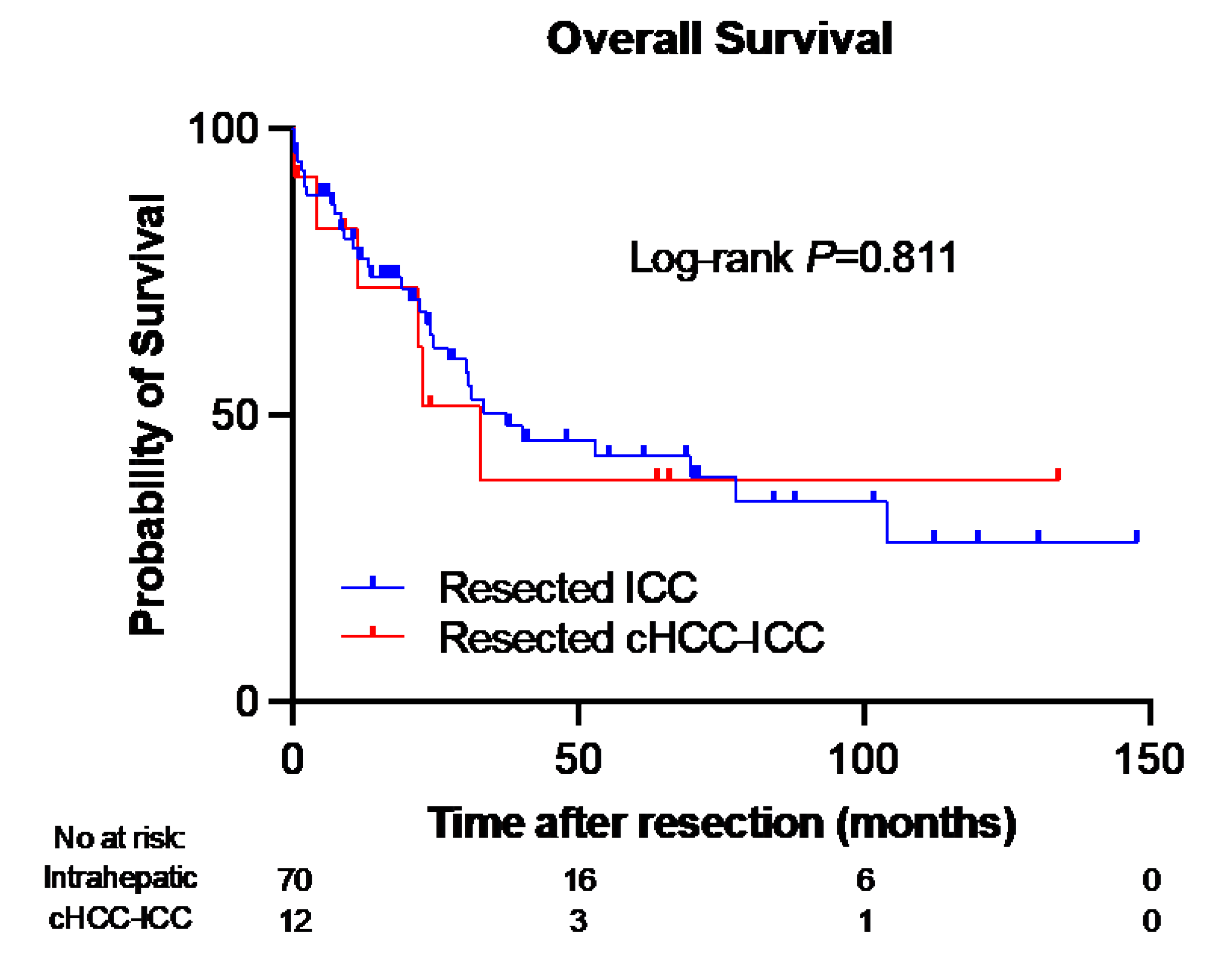

3.7. Overall Survival and Mortality Rates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altekruse, S.F.; Devesa, S.S.; Dickie, L.A.; McGlynn, K.A.; Kleiner, D.E. Histological classification of liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancers in SEER registries. J Registry Manag 2011, 38, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Massarweh, N.N.; El-Serag, H.B. Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Control 2017, 24, 1073274817729245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarnagin, W.R.; Weber, S.; Tickoo, S.K.; Koea, J.B.; Obiekwe, S.; Fong, Y.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Blumgart, L.H.; Klimstra, D. Combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: Demographic, clinical, and prognostic factors. Cancer 2002, 94, 2040–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.Q.; Yan, L.N.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, J.Y.; Luo, H.Z.; Liu, J.W.; Zhou, L.X. Clinicopathological characteristics of 15 patients with combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2007, 6, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maximin, S.; Ganeshan, D.M.; Shanbhogue, A.K.; Dighe, M.K.; Yeh, M.M.; Kolokythas, O.; Bhargava, P.; Lalwani, N. Current update on combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Radiol Open 2014, 1, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutolo, C.; Dell’Aversana, F.; Fusco, R.; Grazzini, G.; Chiti, G.; Simonetti, I.; Bruno, F.; Palumbo, P.; Pierpaoli, L.; Valeri, T.; et al. Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma: What the Multidisciplinary Team Should Know. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.Q.; El-Serag, H.B.; Loomba, R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: Trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.M.; Zhang, X.F.; Wu, L.P.; Sui, C.J.; Yang, J.M. Risk factors for combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: A hospital-based case-control study. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20, 12615–12620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.E.; Lee, S.H.; Yang, J.D.; Hwang, H.P.; Hwang, S.E.; Yu, H.C.; Moon, W.S.; Cho, B.H. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognostic factors in combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2013, 17, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panjala, C.; Senecal, D.L.; Bridges, M.D.; Kim, G.P.; Nakhleh, R.E.; Nguyen, J.H.; Harnois, D.M. The diagnostic conundrum and liver transplantation outcome for combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Transplant 2010, 10, 1263–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.D.; Park, S.J.; Han, S.S.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, S.A.; Ko, Y.H.; Hong, E.K. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma after surgery. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2014, 13, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.W.; Li, Q.F.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, K.; Pu, D.; Chen, X.R.; Li, C.H.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; et al. Clinicopathologic features, treatment, survival, and prognostic factors of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: A nomogram development based on SEER database and validation in multicenter study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2022, 48, 1559–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantajitr, S.; Wilasrusmee, C.; Lertsitichai, P.; Phromsopha, N. Combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: Clinical features and prognostic study in a Thai population. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2006, 13, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayas, M.F.; Affas, S.; Ayas, Z.; Chand, M.; Hadid, T. Primary Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma: A Case of Underdiagnosed Primary Liver Cancer. Cureus 2021, 13, e18224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yau, T.; Tang, V.Y.; Yao, T.J.; Fan, S.T.; Lo, C.M.; Poon, R.T. Development of Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging system with treatment stratification for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1691–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farges, O.; Fuks, D.; Le Treut, Y.P.; Azoulay, D.; Laurent, A.; Bachellier, P.; Nuzzo, G.; Belghiti, J.; Pruvot, F.R.; Regimbeau, J.M. AJCC 7th edition of TNM staging accurately discriminates outcomes of patients with resectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: By the AFC-IHCC-2009 study group. Cancer 2011, 117, 2170–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Liao, Y.; Li, J.; Dong, H.; Peng, H.; Xu, W.; Fan, Z.; Gao, F.; Liu, C.; et al. Prediction of Survival and Analysis of Prognostic Factors for Patients With Combined Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Cholangiocarcinoma: A Population-Based Study. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 686972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garancini, M.; Goffredo, P.; Pagni, F.; Romano, F.; Roman, S.; Sosa, J.A.; Giardini, V. Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: A population-level analysis of an uncommon primary liver tumor. Liver Transpl 2014, 20, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilchez, V.; Shah, M.B.; Daily, M.F.; Pena, L.; Tzeng, C.W.; Davenport, D.; Hosein, P.J.; Gedaly, R.; Maynard, E. Long-term outcome of patients undergoing liver transplantation for mixed hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma: An analysis of the UNOS database. HPB (Oxford) 2016, 18, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.W.; Chok, K.S.H. Importance of surgical margin in the outcomes of hepatocholangiocarcinoma. World J Hepatol 2017, 9, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, S.; Belghiti, J. Oncologic resection for malignant tumors of the liver. Ann Surg 2011, 253, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaufrere, A.; Calderaro, J.; Paradis, V. Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: An update. J Hepatol 2021, 74, 1212–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, R.; Chen, L.; Zhang, C.; Fujita, M.; Li, R.; Yan, S.M.; Ong, C.K.; Liao, X.; Gao, Q.; Sasagawa, S.; et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Profiling of Combined Hepatocellular and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Reveals Distinct Molecular Subtypes. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 932–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leoni, S.; Sansone, V.; Lorenzo, S.; Ielasi, L.; Tovoli, F.; Renzulli, M.; Golfieri, R.; Spinelli, D.; Piscaglia, F. Treatment of Combined Hepatocellular and Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penzkofer, L.; Groger, L.K.; Hoppe-Lotichius, M.; Baumgart, J.; Heinrich, S.; Mittler, J.; Gerber, T.S.; Straub, B.K.; Weinmann, A.; Bartsch, F.; et al. Mixed Hepatocellular Cholangiocarcinoma: A Comparison of Survival between Mixed Tumors, Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Hepatocellular Carcinoma from a Single Center. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.W.; Wu, T.C.; Lin, H.Y.; Hung, C.M.; Hsieh, P.M.; Yeh, J.H.; Hsiao, P.; Huang, Y.L.; Li, Y.C.; Wang, Y.C.; et al. Clinical features and outcomes of combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma versus hepatocellular carcinoma versus cholangiocarcinoma after surgical resection: A propensity score matching analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 2021, 21, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, D.; Donadon, M.; Lleo, A.; Aghemo, A.; Roncalli, M.; di Tommaso, L.; Torzilli, G. Surgical Treatment of Hepatocholangiocarcinoma: A Systematic Review. Liver Cancer 2020, 9, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Shi, G. Survival outcomes of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma compared with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A SEER population-based cohort study. Cancer Med 2022, 11, 692–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Chung, G.E.; Yu, S.J.; Hwang, S.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Yoon, J.H.; Lee, H.S.; Yi, N.J.; Suh, K.S.; et al. Long-term prognosis of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma after curative resection comparison with hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011, 45, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.S.; Lee, K.W.; Heo, J.S.; Kim, S.J.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, Y.I.; Joh, J.W. Comparison of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma with hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Today 2006, 36, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, Y.I.; Hwang, S.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, K.H.; Ahn, C.S.; Moon, D.B.; Ha, T.Y.; Song, G.W.; Jung, D.H.; Lee, J.W.; et al. Postresection Outcomes of Combined Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Cholangiocarcinoma, Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg 2016, 20, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Yang, D.; Tang, C.L.; Cai, P.; Ma, K.S.; Ding, S.Y.; Zhang, X.H.; Guo, D.Y.; Yan, X.C. Combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma (biphenotypic) tumors: Clinical characteristics, imaging features of contrast-enhanced ultrasound and computed tomography. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschrich, J.; Kobus, Z.; Geisel, D.; Halskov, S.; Rossner, F.; Roderburg, C.; Mohr, R.; Tacke, F. The Diagnostic Approach towards Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma-State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, K.C.; Lee, H.; Choi, M.S.; Lee, J.H.; Paik, S.W.; Yoo, B.C.; Rhee, J.C.; Cho, J.W.; Park, C.K.; Kim, H.J. Clinicopathologic features and prognosis of combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg 2005, 189, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell, L.C.; Harding, J.J.; Shia, J.; Abou-Alfa, G.K. Combined intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin Clin Oncol 2016, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.F.; Beal, E.W.; Bagante, F.; Chakedis, J.; Weiss, M.; Popescu, I.; Marques, H.P.; Aldrighetti, L.; Maithel, S.K.; Pulitano, C.; et al. Early versus late recurrence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after resection with curative intent. Br J Surg 2018, 105, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.S.; Zhang, X.F.; Weiss, M.; Popescu, I.; Marques, H.P.; Aldrighetti, L.; Maithel, S.K.; Pulitano, C.; Bauer, T.W.; Shen, F.; et al. Recurrence Patterns and Timing Courses Following Curative-Intent Resection for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2019, 26, 2549–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoh, T.; Hatano, E.; Seo, S.; Okuda, Y.; Fuji, H.; Ikeno, Y.; Taura, K.; Yasuchika, K.; Okajima, H.; Kaido, T.; et al. Long-Term Survival of Recurrent Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: The Impact and Selection of Repeat Surgery. World J Surg 2018, 42, 1848–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, S.M.; Jarnagin, W.R.; Klimstra, D.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Fong, Y.; Blumgart, L.H. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Resectability, recurrence pattern, and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg 2001, 193, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, D.H.; Hwang, S.; Song, G.W.; Ahn, C.S.; Moon, D.B.; Kim, K.H.; Ha, T.Y.; Park, G.C.; Hong, S.M.; Kim, W.J.; et al. Longterm prognosis of combined hepatocellular carcinoma-cholangiocarcinoma following liver transplantation and resection. Liver Transpl 2017, 23, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).